Antiphospholipid syndrome is an acquired autoimmune thrombophilia characterized by a series of phenomena consisting of thrombosis (venous and / or arterial or microvascular) and/or loss of pregnancy or complications in association with persistent positive antiphospholipid antibodies. Other systemic manifestations predict this pathology, and there are multiple causes that lead to bleeding complications in this context. In this article, the main characteristics of the haemorrhagic involvement of APS will be reviewed and advice will be offered regarding the management of these manifestations.

Materials and methodsA narrative review of the literature was conducted by searching the PubMed databases, Medline search engine, and Embase until November 2020. In which bleeding complications were characterized under the context of antiphospholipid syndrome.

Results290 articles were found. By excluding the articles that did not meet the objective of the study, duplicates and letters to the editor, a total of 55 articles remained, which were included for the development of this article.

ConclusionsAntiphospholipid syndrome has classically been described as a prothrombotic disorder associated with obstetric comorbidity, however, due to its pathophysiology, many other manifestations are presumed, including haemorrhagic ones. Due to the scarce scientific evidence on this type of manifestations, it is necessary to continue with more in-depth studies and case reports that provide information about haemorrhagic manifestations as complications of antiphospholipid syndrome.

El síndrome antifosfolípido es una trombofilia autoinmune adquirida que se caracteriza por una serie de fenómenos consistentes en trombosis (venosa y/o arterial o microvascular) y/o la pérdida del embarazo o complicaciones en asociación con anticuerpos antifosfolípidos positivos persistentes. Otras manifestaciones sistémicas comprende esta patología y existen múltiples causas que conllevan complicaciones hemorrágicas en tal contexto. En este artículo se revisan las principales características del compromiso hemorrágico de SAF y se ofrece asesoramiento en relación con el manejo de estas manifestaciones.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó una revisión narrativa de la literatura mediante la búsqueda en las bases de datos PubMed, motor de búsqueda de Medline, y Embase hasta noviembre del 2020. En dicha revisión se caracterizaron las complicaciones hemorrágicas en el contexto de síndrome antifosfolípido.

ResultadosSe encontraron 290 artículos. Al excluir aquellos que no cumplían con el objetivo del estudio, duplicados y cartas al editor, quedaron un total de 55, que fueron incluidos para el desarrollo del presente artículo.

ConclusionesEl síndrome antifosfolípido clásicamente se ha descrito como un trastorno protrombótico y asociado a comorbilidad obstétrica, sin embargo, por su fisiopatología se presumen muchas otras manifestaciones, entre ellas las hemorrágicas. Debido a la escasa evidencia científica sobre este tipo de manifestaciones, es necesario continuar con estudios más profundos y reportes de casos que aporten información acerca de las manifestaciones hemorrágicas como complicaciones del síndrome antifosfolípido.

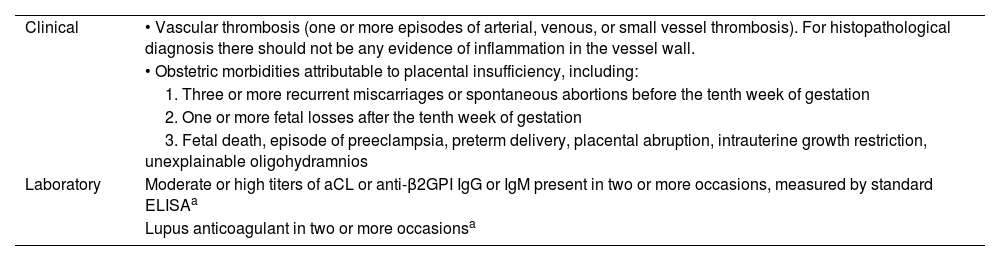

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is described as a condition of autoimmune trombophilia in which the patients have circulating antibodies against the plasma proteins that bind to membrane phospholipids.1 Currently, the criteria used to diagnose APS are those of Sydney (2006) (Table 1),1,2 and require the documentation of vascular thrombosis or obstetric complications attributable to placental vascular insufficiency in the presence of at least one APS antibody. The latter include unexplained miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction, intrauterine death, preeclampsia or toxemia, placental abruption, and preterm birth.3 Laboratory criteria require persistent abnormality of one or more of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) tests (that is, at least two abnormal measurements (12 weeks apart) that include elevated anti-cardiolipin (ACL) antibodies, anti-β2-glycoprotein I (anti-β2GPI) antibodies, or one lupus anticoagulant (LA); these antibodies require a specific titration to be considered positive, since the laboratory reference value alone is not sufficient and they must be in high titers, defined by levels > 40 for anticardiolipin and 99th percentile for anti-β2GPI.4

Sídney research criteria for the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome.1

| Clinical | • Vascular thrombosis (one or more episodes of arterial, venous, or small vessel thrombosis). For histopathological diagnosis there should not be any evidence of inflammation in the vessel wall. |

| • Obstetric morbidities attributable to placental insufficiency, including: | |

| 1. Three or more recurrent miscarriages or spontaneous abortions before the tenth week of gestation | |

| 2. One or more fetal losses after the tenth week of gestation | |

| 3. Fetal death, episode of preeclampsia, preterm delivery, placental abruption, intrauterine growth restriction, unexplainable oligohydramnios | |

| Laboratory | Moderate or high titers of aCL or anti-β2GPI IgG or IgM present in two or more occasions, measured by standard ELISAa |

| Lupus anticoagulant in two or more occasionsa |

Clinical and laboratory criteria are required for diagnosis.

aCL: anticardiolipin; aPL: antiphospholipid; β2GPI: β2-glycoprotein I; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; Ig: immunoglobulin; ISTH SSC: International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis, Scientific and Standardization Subcommittee.

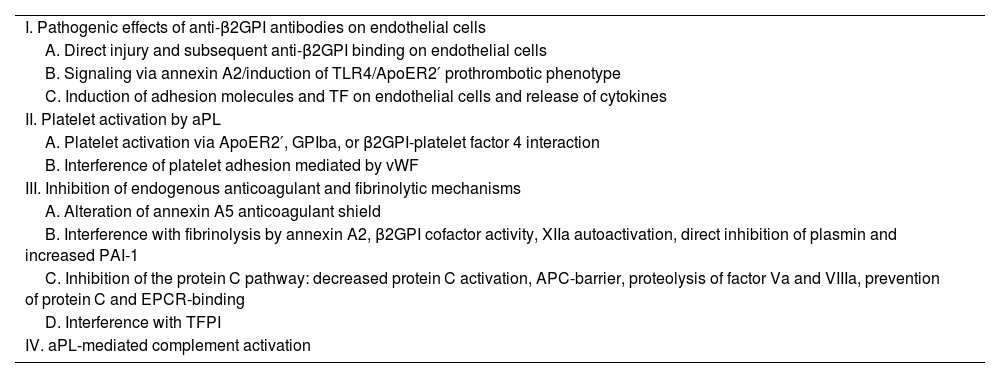

Some patients may even have negative results in aPL tests and at the same time present signs and symptoms typical of the disease; this case is called seronegative APS.5 In recent years, research on APS has increased the understanding of the pathogenic process and encouraged the systematic search in patients with a high suspicion of APS, for a better detection of aPLs. There is increasing evidence that complement activation plays a key role in the pathogenesis of APS (Table 2).2

Pathogenic mechanisms of antiphospholipid syndrome.2

| I. Pathogenic effects of anti-β2GPI antibodies on endothelial cells |

| A. Direct injury and subsequent anti-β2GPI binding on endothelial cells |

| B. Signaling via annexin A2/induction of TLR4/ApoER2′ prothrombotic phenotype |

| C. Induction of adhesion molecules and TF on endothelial cells and release of cytokines |

| II. Platelet activation by aPL |

| A. Platelet activation via ApoER2′, GPIba, or β2GPI-platelet factor 4 interaction |

| B. Interference of platelet adhesion mediated by vWF |

| III. Inhibition of endogenous anticoagulant and fibrinolytic mechanisms |

| A. Alteration of annexin A5 anticoagulant shield |

| B. Interference with fibrinolysis by annexin A2, β2GPI cofactor activity, XIIa autoactivation, direct inhibition of plasmin and increased PAI-1 |

| C. Inhibition of the protein C pathway: decreased protein C activation, APC-barrier, proteolysis of factor Va and VIIIa, prevention of protein C and EPCR-binding |

| D. Interference with TFPI |

| IV. aPL-mediated complement activation |

aPL: antiphospholipid; β2GPI: β2-glycoprotein I; EPCR: endothelial cell protein C receptor; GP: glycoprotein; PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; aPC: activated protein C; TF: tissue factor; TFPI: tissue factor pathway inhibitor; TLR4: Toll-like receptor 4; vWF: Von Willebrand factor.

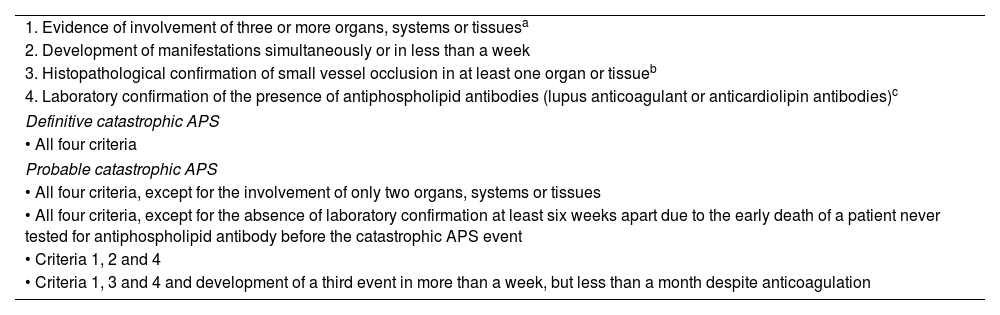

Currently, APS can be divided into the following subcategories: a) primary APS, in the absence or autoimmune disease; b)secondary APS, associated with other autoimmune diseases; c) seronegative APS, which includes patients with a test totally negative for the disorder and despite this, it is suspected for clinical reasons, without ignoring the existence of other antibodies such antiprothrombin or antiphosphatidylinositol, among others, and d) catastrophic APS, which manifests itself as disseminated thrombosis in large and small vessels. The latter are the most affected, with the consequent multiple organ insufficiency, which is defined as the involvement of three or more organs or systems in one week (Table 3).6–8 However, hemorrhagic manifestations are infrequent but highly fatal in these patients. Among them, acquired thrombocytopathies, thrombocytopenia and inhibitors against specific coagulation factors have been described. Lupus anticoagulant-hypoprothrombinemia syndrome, acquired Von Willebrand syndrome, acquired inhibitor of specific coagulation factor (factor VIII) and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage are described in this paper. The main characteristics of the hemorrhagic commitment of APS are reviewed in each of these cases and advice regarding the management of these manifestations is offered.

Proposed classification criteria for catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome.3,4

| 1. Evidence of involvement of three or more organs, systems or tissuesa |

| 2. Development of manifestations simultaneously or in less than a week |

| 3. Histopathological confirmation of small vessel occlusion in at least one organ or tissueb |

| 4. Laboratory confirmation of the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant or anticardiolipin antibodies)c |

| Definitive catastrophic APS |

| • All four criteria |

| Probable catastrophic APS |

| • All four criteria, except for the involvement of only two organs, systems or tissues |

| • All four criteria, except for the absence of laboratory confirmation at least six weeks apart due to the early death of a patient never tested for antiphospholipid antibody before the catastrophic APS event |

| • Criteria 1, 2 and 4 |

| • Criteria 1, 3 and 4 and development of a third event in more than a week, but less than a month despite anticoagulation |

Clinical evidence of venous occlusion, confirmed by imaging techniques when appropriate. Renal involvement is defined by a 50% increase in serum creatinine, severe systemic hypertension (> 180/100 mm Hg) or proteinuria (> 500 mg/24 h).

For histopathological confirmation there must be significant evidence of thrombosis, although, in contrast with the Sydney 2006 criteria, vasculitis may occasionally coexist.

If the patient had not previously been diagnosed with an antiphospholipid syndrome, laboratory confirmation requires that the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies be detected on two or more occasions, at least six weeks apart (not necessarily at the time of the event), according to the preliminary criteria proposed for the classification of defined antiphospholipid syndrome.

A narrative literature review was conducted for this writing by searching in PubMed—Medline search engine—and Embase databases; articles published until November 2020 were obtained. The MESH terminology was used, with the following search equation ((Antiphospholipid Syndrome) AND (Bleeding Disorders)) OR (Hemorrhage Disease). Articles in English and Spanish, case reports, topic reviews and descriptive clinical studies in adults were included. Articles that did not meet the objective of the study, duplicate articles, and letters to the editor were excluded.

At the end of the search, the articles were stored in a database created in Excel. Thus, duplicate articles were excluded and the process of selection of those relevant to this publication began. Those that included the keywords in the title or in the abstract were taken into account. It was revised that each article met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and finally, a consensus among all the authors was reached to unify and review the database.

ResultsSubsequent to the initial search, 290 articles were found in Medline and Embase. When those that did not meet the objective of the study, duplicates and letters to the editor were excluded, remaining in total 55 articles, which were included for the preparation of this writing. The findings of the literature review are described below.

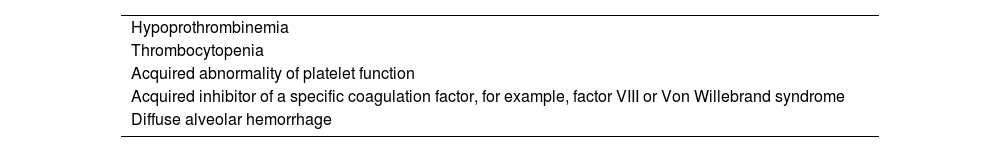

DiscussionThe concomitant presence of a hemostasis disorder should be taken into account when patients with APS have a bleeding tendency (Table 4).

Causes of bleeding in the antiphospholipid syndrome.10

| Hypoprothrombinemia |

| Thrombocytopenia |

| Acquired abnormality of platelet function |

| Acquired inhibitor of a specific coagulation factor, for example, factor VIII or Von Willebrand syndrome |

| Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage |

The causes of bleeding in APS include acquired thrombocytopathies, thrombocytopenia, and inhibitors against specific coagulation factors.9

Lupus anticoagulant-hypoprothrombinemia syndromeThis syndrome is characterized by the association of acquired deficiency of factor II (prothrombin) in the presence of LA. It is an extremely rare syndrome, with less than 100 cases described in the literature.10

The coagulation factor II, prothrombin, is a vitamin K-dependent coagulation cofactor which is cleaved by the factor Xa to form thrombin.11 In turn, thrombin is the responsible for the induction of aggregation and activation of platelets and several other mediators in the coagulation cascade. While inherited factor II deficiency is a rare recessive disorder, its acquired deficiency is a frequent finding in severe liver disease, vitamin K deficiency, as well as in the treatment with vitamin K antagonists.12 In these cases, other coagulation factors such as VII and X, and in some cases the factor V, are also reduced. In rare cases, isolation of acquired factor II deficiency can be seen in patients with circulating lupus anticoagulant.13,14

The first case was described by Rapaport et al.15 in 1960, but it was not until more than 20 years after that Bajaj et al.16 demonstrated the presence of antiprothrombin antibodies, which although they do not prevent its activation, they produce hypoprothrombinemia secondary to the rapid clearance of antigen-antibody complexes from the circulation. In this context, anti-factor II antibodies are responsible for the deficiency of prothrombin. Unlike classical APS, this rare condition can cause severe life-threatening bleeding.10,16 Prothrombin is one of the target antigens of aPL and therefore, anti-prothrombin antibodies belong to the family of APS antibodies.17,18 It is important to take into account the detection of anti-prothrombin antibodies and the follow-up with factor II inhibitors within the diagnostic and therapeutic approach of these patients, but they are not discussed in this review.

The disease is more frequent in young adults, and the conditions associated include autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as well as infectious diseases, but in some occasions it is associated with lymphoma or it may be drug-induced.19–21 The usual treatment of lupus anticoagulant syndrome (hypoprothrombinemia) consists in corticotherapy associated with other immunosupresants (cyclophosphamide, azathioprine or rituximab), with the purpose of reducing the risk of bleeding and eliminating the inhibitor.22

ThrombocytopeniaThrombocytopenia is frequent in patients with APS, and approximately 20%–40% of patients with APS have different degrees of thrombocytopenia (usually between 70,000 and 120,000 platelets); however, a count of less than 100,000 platelets is considered a extracriteria manifestation by consensus.23 The decrease in the number of platelets is usually mild to moderate and is rarely severe enough to cause hemorrhagic complications or to affect anticoagulant therapy.24,25 In some cases it can be serious and may require intensive treatment.

Cyclic thrombocytopenia may be the only manifestation of APS, but it is more common to find it together with the classic manifestations of this disease.26–29 Apart from some reports of an association between thrombocytopenia and aPL in SLE and in primary APS, available data on this association are scarce.30,31 Recent studies have also demonstrated that the prevalence of thrombocytopenia in patients with primary APS is similar to that observed in patients with APS and associated SLE.32,33 In addition, elevated aPL concentrations have been found in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.34,35

The majority of patients with APS and thrombocytopenia have antibodies against integrin αIIbβ3 and/or glycoprotein Ib-IX complex.36 Patients who present with immune thrombocytopenic purpura have increased aPL and are more prone to thrombosis.37 aPL and the antibodies against platelet membrane glycoprotein are simultaneously present in approximately 70% of patients with immune thrombocytopenia.38 In a prospective cohort study, at 5-year thrombosis-free survival in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura, 39% were aPL-positive and 98% were negative.39 However, it must be taken into account that thrombocytopenia itself is not protective against thrombosis in these patients.

Acquired specific coagulation factor (factor VIII) inhibitorThe development of autoantibodies (or inhibitors) against a coagulation factor can cause hemorrhagic manifestations. The most commonly involved factor is factor VIII (FVIII), a potentially serious and probably underrecognized disorder that affects patients with autoimmune diseases, presumably due to the underlying immune dysregulation and the resulting development of autoantibodies.40

This phenomenon, commonly known as “acquired hemophilia” or “autoimmune hemophilia”, usually presents itself with new-onset bleeding and may be recurrent. Therefore, its early identification is critical to eliminate the inhibitor with targeted therapies. Bleeding due to acquired FVIII inhibitors may be serious and life-threatening, for which urgent diagnosis and treatment are crucial.41

Considering that autoimmune diseases are among the underlying conditions most commonly associated with acquired FVIII inhibitors, it is necessary to perform coagulation studies that include activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) in patients with autoimmune disease presenting with excessive ecchymosis or other bleeding symptoms. If the aPTT is prolonged alone, acquired FVIII inhibitors should be suspected, and further evaluation for this condition should be performed urgently.42

In occasions, those who are affected present an isolated prolonged aPTT in an asymptomatic manner during routine laboratory tests; therefore, all patients presenting with a prolonged aPTT should undergo plasma cross-testing to identify the circulating inhibitor or the deficiency of the factor, and thus determine the underlying cause, which includes patients with a minimally prolonged aPTT accompanied by bleeding, as well as those with a significant prolongation and are asymptomatic.

The initial clinical presentation may not provide the necessary clues to differentiate between a coagulation factor inhibitor (associated with bleeding) and a lupus anticoagulant (associated with thrombosis), both of which may prolong the aPTT.43 Their coexistence (FVIII and lupus anticoagulant inhibitors) has been described in the literature, so it should always be considered.44,45

Acquired von Willebrand syndromeAnother possible cause of bleeding in patients with APS is acquired Von Willebrand syndrome, which should be suspected in all patients presenting with a late-onset bleeding diathesis and without a personal or family history of coagulopathy. Among its symptoms, mucocutaneous bleeding predominates, but gastrointestinal or post-surgical hemorrhages have also been described.46 Regarding its pathogenesis, the factor is normally produced, although it is rapidly removed from plasma due to the presence of circulating antibodies against Von Willebrand factor. This disorder can also be seen in tumor involvement by absorption of Von Willebrand factor by tumor cells, or proteolysis of Von Willebrand.47

In association with APS, the causative mechanism of the acquired Von Willebrand syndrome is the presence of circulating antibodies, which can be directed against functional or non-functional domains of the factor and generate the removal from plasma through the formation of immune complexes. The latter are eliminated by the reticuloendothelial system.48

The diagnosis is based on evaluating the deficiency of Von Willebrand factor; likewise, the detection of the antibody against the factor can be performed using methods of Elisa. The treatment is based on controlling the acute hemorrhage and treating the underlying disease.49

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhageAlveolar hemorrhage is characterized by bleeding into the alveolar space as a result of both an immunological and non-immune process; it is a rare manifestation of primary APS with a high rate of morbidity and mortality.50 Until now, the literature in this regard is limited to reports and case series, and it is not clear if a pathogenic association with APS has been found.51

As a hypothesis, it is suggested that aPLs induce upregulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules, with the subsequent recruitment of neutrophils and migration to the alveolar septa, which generates tissue destruction and hemorrhage, a phenomenon of capillaritis.51,52 Yachoui et al.51 described a series of cases with alveolar hemorrhage in the context of high aPLs or APS, in a follow-up period of 16 years in which they included 17 patients with alveolar hemorrhage, of whom 10 met the diagnostic criteria for APS and 7 only had high aPL titers. Predominance in men was found, also reported in other case series,53 with a higher prevalence between the fourth and fifth decades of life.51,52

In most case series, the average time reported between the diagnosis of APS and the episode of alveolar hemorrhage is 12 months, with a time interval of 0–48 months; the most commonly elevated antibody is LA, followed by anticardiolipin antibodies (usually IgG) and b2 glycoprotein 1.51–54

The main symptomatology consists in dyspnea and hemoptysis, with imaging findings of alveolar occupation of ground-glass type in the chest CT and evidence of findings of hemosiderin-laden macrophages and inflammatory infiltrate predominantly neutrophilic on the fiberoptic bronchoscopy.51–53 In patients who undergo lung biopsy (open or transbronchial), variability among histological findings has been demonstrated, from capillaritis (without thrombosis) to diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.52,55

With respect to management, it is variable, and remissions of the disease have been described even without medical treatment.51 The use of corticosteroids (prednisolone in pulses or high-doses) is described as initial therapy, with variable response. Likewise, the use of immunomodulators such as cyclophosphamide and rituximab in patients refractory to management with corticosteroids or relapse of the disease has evidenced a better response compared to corticosteroid sparing agents such as azathioprine or methotrexate.53 Regarding anticoagulation, it is suggested to continue it or start it early, since thrombotic event s have been described during the episodes of smooth alveolar hemorrhage.51,53,55

Recurrence of the disease is common, especially in patients using glucocorticoids in combination therapy with mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine. In series such as the one by Yachoui et al.,51 up to 48% of the patients presented complete remission of the disease.

ConclusionAPS has been classically described as a prothrombotic disorder associated with obstetric comorbidity, but further study of its pathophysiology, increased diagnosis, case reports, and research related to this syndrome have put in evidence many other manifestations that can be associated with the presence of antibodies against phospholipids: among these, the hemorrhagic manifestations, not only due to complications of anticoagulant therapy, but also due to mechanisms characteristic of APS that lead to bleeding, in many cases life-threatening and that imply a rapid initiation of immunomodulatory treatments. The low frequency of these manifestations may be due to the lack of reporting and knowledge that APS can present bleeding and not only thrombosis. It is expected that this review will serve to initiate more in-depth studies and case reports of patients with hemorrhagic manifestations in APS.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest for the preparation of this article.