Anterior glenohumeral dislocation in patients older than 60 years is related to rotator cuff lesion because of its pre-existing degenerative condition. However, in this age group, the scientific evidence fails to elucidate whether rotator cuff lesions are the cause or consequence of recurrent shoulder instability. The objective of this paper is to describe the prevalence of rotator cuff injuries in a series of consecutive shoulders in patients older than 60 years who suffered a first episode of traumatic glenohumeral dislocation, and its correlation with rotator cuff injuries in both shoulders.

MethodsRetrospectively, 35 patients over 60 years of age who had a first episode of unilateral traumatic anterior glenohumeral dislocation and who had MRI of both shoulders were studied, evaluating both shoulders with MRI to determine the structural damage correlation of the rotator cuff and long head of the biceps between them.

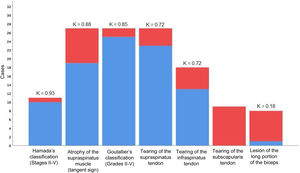

ResultsWhen assessing the existence of partial or complete injury to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons, the concordance on the affected and healthy sides, we have shown concordant results on both sides in 88.6 and 85.7%, respectively. The Kappa concordance coefficient was 0.72 for supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons tear. Of the total of 35 cases evaluated, 8 (22.8%) presented at least some alteration in the tendon of the long head of the biceps on the affected side and only one (2.9%) on the healthy side, where the Kappa coefficient of concordance was 0.18. Of the 35 cases evaluated, 9 (25.7%) presented at least some retraction in the tendon of the subscapularis muscle on the affected side, while no participant showed signs of retraction in the tendon of this muscle on the healthy side.

ConclusionsOur study has found a high correlation of the presence of a postero-superior rotator cuff injury after presenting a glenohumeral dislocation between the shoulder that has suffered the event and the presumably healthy contralateral shoulder. Nevertheless, we have not found this same correlation with subscapularis tendon injury and medial biceps dislocation.

En el contexto de la luxación glenohumeral anterior, en los pacientes mayores de 60 años, el manguito rotador posterosuperior es más susceptible a lesionarse debido a su condición degenerativa preexistente. Sin embargo, en este grupo etario, la evidencia científica no logra dilucidar si las lesiones del manguito rotador son causa o consecuencia de la inestabilidad recurrente de hombro. El objetivo de este trabajo es describir la prevalencia de lesiones del manguito rotador en una serie de hombros consecutivos en mayores de 60 años que experimentaron un primer episodio de luxación glenohumeral traumática, y su correlación con lesiones del manguito rotador en el hombro contralateral.

MétodosSe estudiaron de forma retrospectiva 35 pacientes mayores de 60 años que presentaron un primer episodio de luxación glenohumeral anterior traumática unilateral y que contaban con RMN de ambos hombros, determinando la correlación lesional del manguito rotador y de la porción larga del bíceps entre el hombro que presentó el evento traumático y el contralateral, presumiblemente sano.

ResultadosAl valorar la existencia de lesión parcial o completa de los tendones supraespinoso e infraespinoso, la concordancia en el lado afectado y sano, hemos evidenciado resultados concordantes en ambos lados en el 88,6 y 85,7%, respectivamente. El coeficiente de concordancia kappa resultó ser de 0,72 para la lesión del tendón supraespinoso y para la lesión del tendón infraespinoso. Del total de 35 casos evaluados, 8 (22,8%) presentaron al menos alguna alteración en el tendón de la porción larga del bíceps en el lado afectado y solo uno (2,9%) en el lado sano, resultando ser el coeficiente de concordancia kappa de 0,18. De los 35 casos evaluados, 9 (25,7%) presentaron al menos alguna retracción en el tendón del músculo subescapular en el lado afectado, mientras que ningún participante evidenció signos de retracción en el tendón de este músculo en el lado sano.

ConclusionesLas lesiones del manguito posterosuperior se encuentran presentes con incidencia similar en hombros que han presentado una luxación y el contralateral asintomático. Sin embargo, no hemos encontrado esta misma correlación entre ambos hombros respecto a la lesión del tendón subescapular y la luxación medial del bíceps, encontrándose con mayor incidencia en el hombro que ha presentado la luxación traumática.

In patients over the age of 60 years, the posterosuperior rotator cuff is more susceptible to injury due to its pre-existing degenerative condition.1 It is therefore considered that the partial or total tearing of the tendons which form the rotator cuff occurs due to excessive tensile forces during glenohumeral luxation within previously degenerative tissue.2–4 Nevertheless, in this age group scientific evidence has not been able to elucidate whether rotator cuff lesions are the cause or the effect of recurring shoulder instability.5,6 In fact, the partial as well as the complete lesions of the rotator cuff are often found in imaging tests of asymptomatic patients who are over the age of 60 years, so that the absence of pain prior to dislocation does not rule out the presence of a lesion in these structures prior to the event.7–13

This work aims to describe the prevalence of rotator cuff lesions in a series of consecutive shoulders in patients over the age of 60 years who suffered a first episode of traumatic glenohumeral dislocation, and its correlation with rotator cuff lesions in the contralateral shoulder.

Materials and methodsParticipants and selection criteriaAfter approval by the Ethics Committee of the hospital where the study was performed (internal code 6128), a retrospective study was undertaken of patients older than 50 years who suffered a first episode of unilateral glenohumeral dislocation in 2015 and 2016, and who had been subjected to MR imaging tests of both shoulders within the first 3 months after the traumatic event. The inclusion criteria were defined by a qualified shoulder surgeon (FA), who carried out the questioning and the physical examination. The selected cases were included in the study retrospectively and consecutively in the Hospital Español de Buenos Aires from 1 August 2015 until 1 September 2016. The patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria went on to form a part of the study.

The exclusion criteria were: fracture of the associated proximal humerus, ipsilateral dislocation and/or anterior contralateral glenohumeral dislocation, phobia or contraindication to the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patients with known previous disease in either shoulder were excluded.

Estimation of sample sizeConsidering a prevalence of 50% partial or total lesions in the rotator cuff in individuals over the age of 50 years, and assuming an expected agreement of 0.7 (Ke) and a minimum acceptable agreement of 0.21 (K0) (Koch 1977), with an α=0.05 and a β=0.2, we estimated analysing at least 32 subjects.7–13

Evaluation of magnetic resonance imagingThe evaluated patients were subjected to a standardized bilateral MR imaging test without contrast to determine the incidence of rotator cuff tears following the unilateral dislocation of a shoulder, and the prevalence of similar findings in the contralateral shoulder.

All of the subjects were subjected to a standard imaging test protocol using MR apparatus by Magnetom Essenza (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a field intensity of 1.5T, an 18cm field of vision and a dedicated shoulder matrix coil for high resolution images without movement. All of the explorations included slices in the sagittal, coronal and axial planes without contrast. The subjects were in supine decubitus with their head towards the scanner orifice, their arms resting at the sides of the body and the humerus in neutral or slight external rotation.

Magnetic resonance imaging definitionsThe findings of MR imaging were exhaustively evaluated in the following way: tearing of the partial thickness was identified by the presence of tendon discontinuity along its upper (bursal) surface, intrasubstance and/or lower (articular) surface, with a space full of extra-articular fluid in the T2 images. A total thickness tear was differentiated from a partial thickness tear by the presence of discontinuity of the tendon with a fluid-filled space that extended from the articular surface to the bursal surface, as observed chiefly in the T2 images.18 The extension of the musculotendinous retraction was classified as stage 1 (proximal end close to the bone insertion), stage 2 (proximal end at the level of the humeral head) or stage 3 (proximal end at the level of the glenoid) according to Patte.15

Fatty infiltration was divided into 4 grades according to Goutallier's classification: grade 1, muscle with some fatty streaks; grade 2, more fatty infiltration but with more healthy muscle than fatty muscle; grade 3, infiltration of fatty muscle with as much fatty muscle as healthy muscle; or grade 4, more fatty muscle than healthy muscle, according to Goutallier et al.16,20 Atrophy of the SST was identified by the presence of the sign of the tangent.17 The degree of glenohumeral arthropathy associated with the rotator cuff lesion was graded using the classification of Hamada et al.19

This work does not include information on the presence of any type of capsulolabral lesion or any of its anatomical variations (sublabral foramen and/or Buford's complex). Nor was the presence of an associated SLAP lesion evaluated, and this was also the case for chondral and osteochondral lesions, bone oedema, Hill-Sachs’ lesion or a bony Bankart lesion.

Tendinopathy of the long portion of the biceps was diagnosed by the observation of a thickened tendon in the DP or T1 images, or a hyperintense intratendinous signal without alterations in the signal in the T2 images. A partial tear of the biceps was defined as an alteration of the hyperintense signal in T2 or hypointense in T1. A tear in the total thickness of the biceps was defined by the retraction of the tendon and its absence in the bicipital groove (extraarticular part) observed in the axial images in T2, as well as the absence of the intra-articular tendon in the oblique sagittal plane. To evaluate the dislocation of the tendon of the long head of the biceps axial MR images were used, showing an empty bicipital groove and the tendon of the long portion of the biceps outside the same.18

Statistical analysisContinuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as an average and standard deviation. If not, the median and interquartile range were used. Categorical variables were expressed with the number of presentation and percentage. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to determine sample distribution.

McNemar's test was used to compare categorical variables. The Student's t-test was used to compare subgroups for independent samples, or the Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. A value of P<.05 was considered significant.

The kappa coefficient was used to evaluate the concordance between the findings of the imaging tests on the affected and healthy sides. Acceptable concordance was considered to exist when the kappa coefficient was ≥0.70.14

Version 25.0 of IBM® SPSS® Macintosh software was used for data analysis (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, U.S.A.).

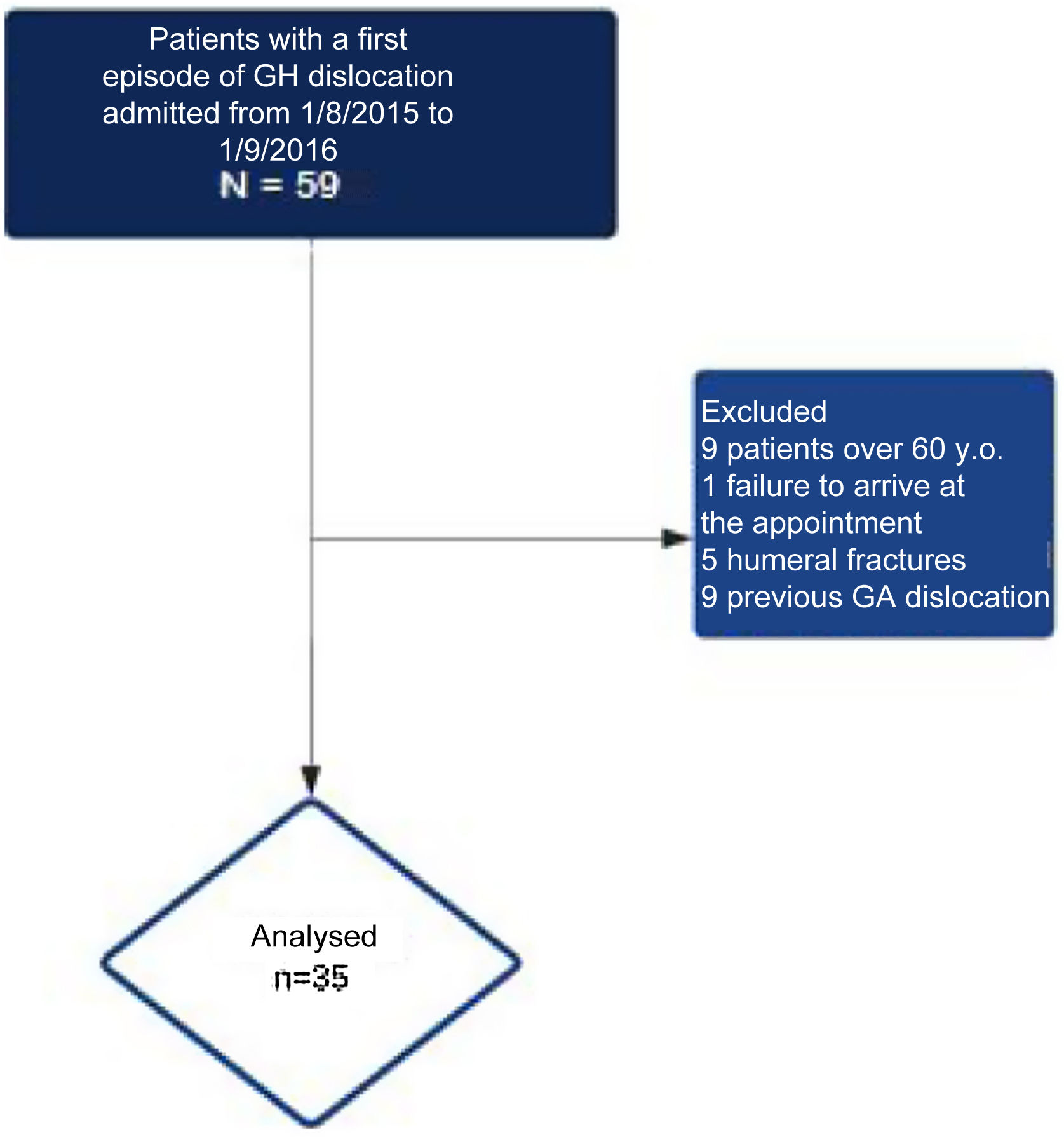

ResultsParticipantsFrom 1 August 2015 to 1 September 2016 a total of 59 subjects were examined, after the confirmed diagnosis of unilateral traumatic glenohumeral dislocation. Of these patients, 24 were not included in the study due to the following reasons: 9 because they were under the age of 60 years, one because they missed the appointment, 5 because of fracture of the associated proximal humerus and 9 due to anterior glenohumeral dislocation (Fig. 1). 35 individuals (35 shoulders) with primary unilateral glenohumeral dislocation therefore took part in this study, in which they were included retrospectively (Fig. 1); their median age was 73 years [interquartile range 64–75], 23 (65.7%) were women and 12 (34.3%) were men. Imaging test findings for both shoulders are shown in Table 1.

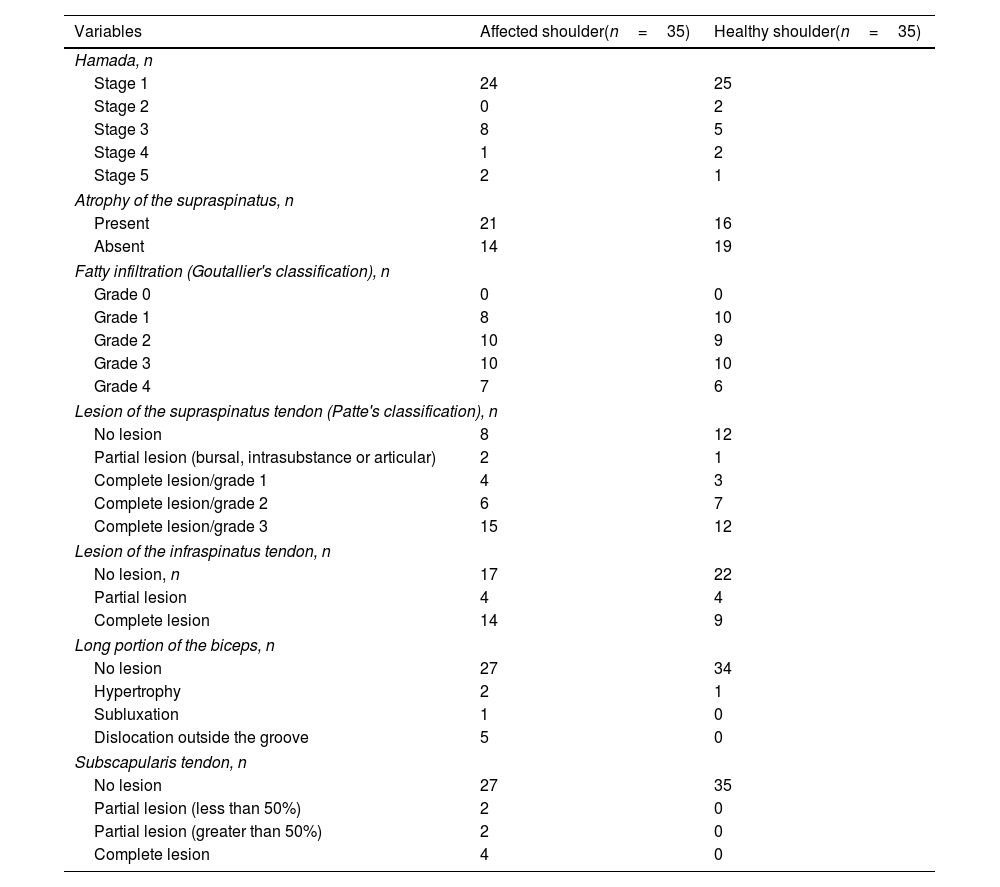

Magnetic resonance imaging findings corresponding to the rotator cuff and long portion of the biceps in the affected shoulder (the one with glenohumeral dislocation) and in the presumably healthy shoulder.

| Variables | Affected shoulder(n=35) | Healthy shoulder(n=35) |

|---|---|---|

| Hamada, n | ||

| Stage 1 | 24 | 25 |

| Stage 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Stage 3 | 8 | 5 |

| Stage 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Stage 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Atrophy of the supraspinatus, n | ||

| Present | 21 | 16 |

| Absent | 14 | 19 |

| Fatty infiltration (Goutallier's classification), n | ||

| Grade 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grade 1 | 8 | 10 |

| Grade 2 | 10 | 9 |

| Grade 3 | 10 | 10 |

| Grade 4 | 7 | 6 |

| Lesion of the supraspinatus tendon (Patte's classification), n | ||

| No lesion | 8 | 12 |

| Partial lesion (bursal, intrasubstance or articular) | 2 | 1 |

| Complete lesion/grade 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Complete lesion/grade 2 | 6 | 7 |

| Complete lesion/grade 3 | 15 | 12 |

| Lesion of the infraspinatus tendon, n | ||

| No lesion, n | 17 | 22 |

| Partial lesion | 4 | 4 |

| Complete lesion | 14 | 9 |

| Long portion of the biceps, n | ||

| No lesion | 27 | 34 |

| Hypertrophy | 2 | 1 |

| Subluxation | 1 | 0 |

| Dislocation outside the groove | 5 | 0 |

| Subscapularis tendon, n | ||

| No lesion | 27 | 35 |

| Partial lesion (less than 50%) | 2 | 0 |

| Partial lesion (greater than 50%) | 2 | 0 |

| Complete lesion | 4 | 0 |

Tearing of the partial thickness was identified in 2 patients on the side that had suffered the event (glenohumeral dislocation), while one case was identified on the healthy side. This indistinctly included discontinuity of the supraspinatus tendon in its bursal face, intrasubstance and/or articular. Complete thickness lesions were identified in 25 of the affected shoulders, while they were also identified in 22 healthy contralateral shoulders. The detail of the degree of tendon retraction is described in Table 1.

Of the 35 cases analyzed, 27 (77.1%) had at least some retraction of the tendon of the supraspinatus muscle on the dislocated side, and this was also the case in 23 instances (65.7%) on the side of the healthy shoulder.

Twenty three of the 27 (85.2%) subjects with retraction of the supraspinatus muscle on the same side as the glenohumeral dislocation also showed retraction of the tendon on the healthy side. None of the 8 subjects who did not suffer retraction of the supraspinatus muscle tendon on the affected side showed signs of retraction on the healthy side. This association was not found to be statistically significant (P=.12).

When evaluating the existence of a partial lesion (bursal, intrasubstance or articular) and a complete lesion, together with concordance on the affected and healthy sides, we found that 31 (88.6%) subjects had concordant results on both sides. Of the total number of concordances, in 23 (65.7%) subjects retraction of the supraspinatus muscle was detected in both shoulders, while in 8 (22.9%) no signs of tendon retraction were observed. Four (11.4%) subjects had discordant results. The kappa concordance coefficient was 0.72.

When evaluating concordance in the Hamada classification identified in the affected side and the healthy side, 34 (97.1%) subjects had concordant results on both sides.19 Of the total number of concordances, in 24 (68.6%) subjects a conserved acromiohumeral interval was identified, while in 10 (28.6%) a compromised interval was found. Only one (2.8%) subject had discordant results. The kappa concordance coefficient was 0.93.

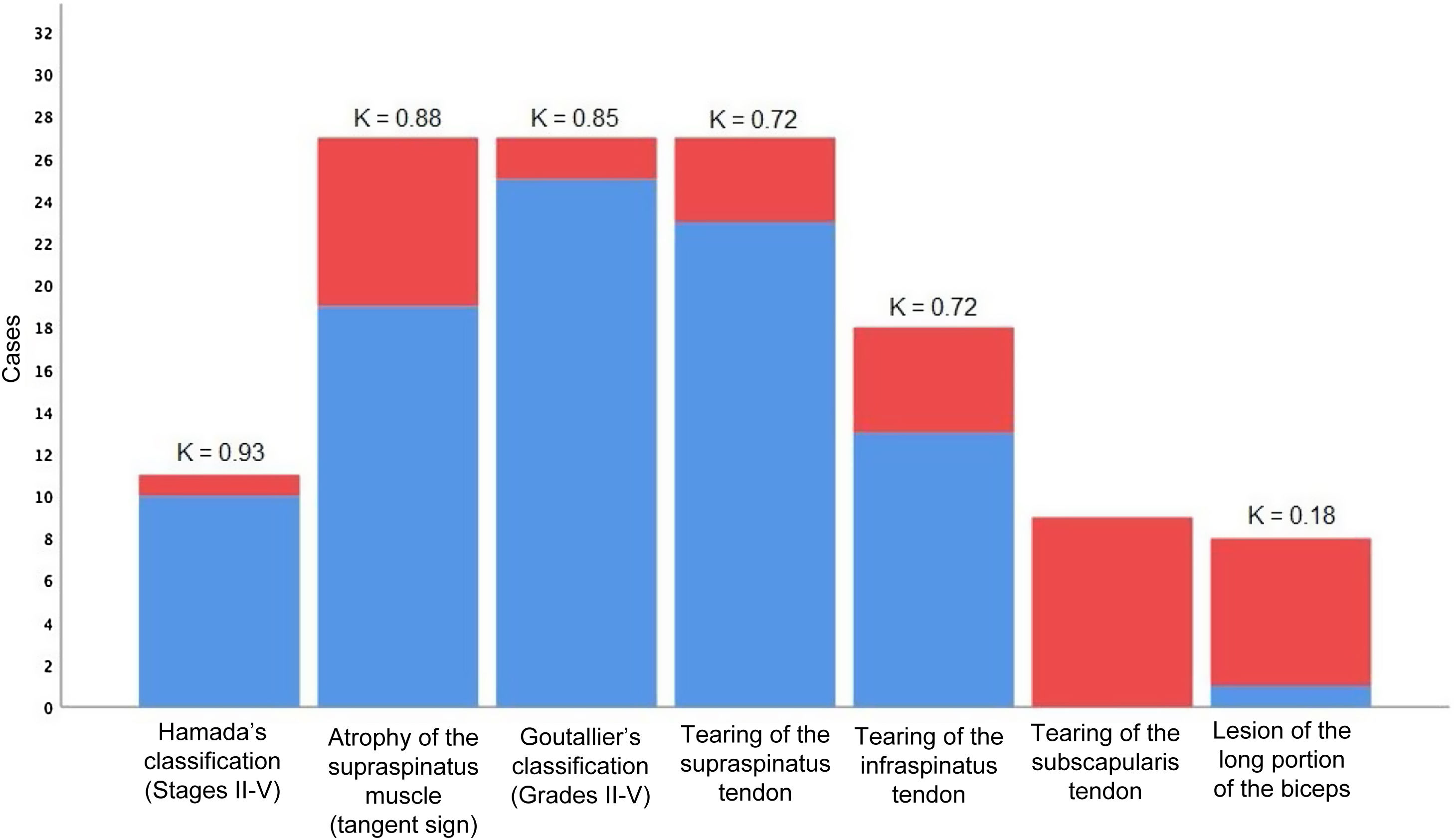

When concordance was evaluated in the compromise identified in the affected and healthy sides, 32 (91.4%) subjects had concordant results in both sides (Fig. 2). Of the total number of concordances, in 24 (68.6%) subjects signs compatible with acetabulization were identified (grades iii to v) and in 8 (22.8%) no compromise was found (grades i and ii). Three (8.6%) subjects had discordant results. The kappa concordance coefficient was 0.78.

Concordance of the pathological findings identified using imaging techniques. The red colour identifies the count of pathological findings in the affected (dislocated) shoulder, and the blue colour identifies the count of concordant pathological findings in the healthy side. The apex of each column shows the respective kappa concordance coefficients for each variable (K), except for subscapularis tendon injury as there was no case of this in a healthy contralateral shoulder.

When concordance was evaluated in the result of the tangent sign in the affected and healthy sides, 33 (94.3%) subjects had concordant results in both sides. Of the total number of concordances, the positive sign was identified in 19 (54.3%) subjects, and the negative sign was found in 14 (40%). Two (5.7%) subjects had discordant results. The kappa concordance coefficient was 0.88.

Classification according to Goutallier et al.16All of the 35 cases analyzed had at least a minimum filtration of fat in the supraspinatus muscle in both sides. When concordance in the affected and healthy sides was evaluated, 33 (94.3%) subjects had concordant results in both sides. Two (5.7%) subjects had discordant results. The kappa concordance coefficient was 0.85.

Classification based on retraction of the infraspinatus muscle tendonOf the total number of 35 cases evaluated, 18 (51.4%) had a complete lesion of the infraspinatus muscle tendon on the affected side, and this was so in 13 (37.1%) cases in the healthy side.

Thirteen of the 18 (72.2%) subjects with a complete lesion and retraction of the infraspinatus muscle tendon in the dislocated side also showed retraction of the tendon in the contralateral side (Table 1). None of the 17 subjects without retraction of the infraspinatus muscle tendon in the dislocated side showed signs of retraction in the contralateral side. This association was not found to be statistically significant (P=.06).

When concordance in the affected and healthy sides was evaluated, 30 (85.7%) subjects had concordant results in both sides (Fig. 2). Of the total number of concordances, in 13 (37.1%) subjects infraspinatus muscle tendon retraction was identified in both shoulders, and in 17 (48.6%) no signs of tendon retraction were detected. Five (14.3%) subjects had discordant results. The kappa concordance coefficient was 0.72.

Classification according to compromise of the tendon of the long portion of the bicepsOf the total number of 35 cases evaluated, 8 (22.8%) had at least one alteration in the tendon of the long portion of the biceps in the affected side, and this was the case for only one subject (2.9%) in the healthy side.

The subject who had dislocation in the brachialis biceps muscle in the dislocated side also had dislocation of the tendon in the muscle in the healthy side (Fig. 2). None of the 27 subjects with no alterations in the tendon of the long portion of the biceps in the affected side showed signs compatible with morphological changes in the tendon of the contralateral muscle. This association was found to be statistically significant (P=.016).

When concordance was evaluated in the affected and healthy sides, 28 (80%) subjects had concordant results in both sides. In only one subject (2.9%) a compromise was detected in the tendon of the long portion of the biceps in both shoulders, while in 27 (77.1%) no signs were found of tendon compromise. Seven (20%) subjects had discordant results. The kappa concordance coefficient was 0.18.

Classification according to compromise and retraction of the subscapularis muscle tendonNine (25.7%) of the 35 cases evaluated had at least one retraction of the subscapularis muscle tendon in the affected side.

No subject had signs of retraction in the tendon of this muscle in the healthy side (Fig. 2). Due to this, in this analysis it was impossible to obtain a P value, as in the group of healthy shoulders the variable is a constant.

DiscussionIn the same way as other authors, we found a high incidence of rotator cuff injury in patients over the age of 60 years.22–26 Yamaguchi et al. found some type of rotator cuff lesion in 35% of healthy shoulders when patients had a contralateral symptomatic lesion.21 Furthermore, they found that the prevalence of a bilateral lesion was directly related to patient age as an independent factor. Consequentially, age may be a distorting factor when we aim of establish the cause of rotator cuff lesion as glenohumeral dislocation.

In our study we found a high concordance between finding signs of degeneration (fatty infiltration, retraction or muscle atrophy) in both shoulders, independently of the history of trauma. This is clinically relevant, as patients with a rotator cuff tear usually recall an injury which significantly increased the symptoms in the shoulder. Nevertheless, pre-existing non-traumatic conditions such as ischaemia and miotendinous degeneration are the chief cause of tendon lesions in this location. This concept was demonstrated by Cofield more than 3 decades ago.22

Based on our findings, only subscapularis tendon lesion and bicipital dislocation are associated with previous trauma. This is not significant in degenerative lesions of the posterosuperior rotator cuff. This agrees with other works which have shown that truly traumatic injuries of the rotator cuff are rare and structurally different from typical degenerative lesions of the supraspinatus tendon and even occur in younger patients.23–25 The majority of degenerative lesions initially affect the supraspinatus muscle tendon with secondary involvement of the subscapularis or infraspinatus muscle tendon (or both).22,28 Lesions of the complete thickness of the subscapularis and the medial dislocation of the long portion of the biceps are more common in patients with relevant trauma, within the context of glenohumeral dislocation.26,27

The association we found between glenohumeral dislocation and lesion of the subscapularis muscle tendon and medial dislocation of the biceps contextualizes what is currently considered to be a truly traumatic injury. Other researchers have therefore proposed that correct diagnosis and surgical repair of traumatic tearing of the subscapularis tendon is crucial for shoulder functioning and they consequently recommend early surgery.27–30

In 1994 Sonnabend published the results of a study of patients over the age of 40 years who had previously suffered a glenohumeral dislocation. In this study a subgroup of 13 patients had persistent pain and weakness 3 weeks after the dislocation.4 These 13 patients were subsequently diagnosed as having undergone rotator cuff tears. Nevertheless, the other asymptomatic patients were not investigated further, and it is not known whether or not they had rotator cuff injuries. Nor were images published that were prior to the event in the symptomatic population. Notwithstanding this, these findings were sufficient for the author to infer and presume causality. Likewise, Hawkins et al. published a study of 61 patients over the age of 40 years who had suffered anterior glenohumeral dislocation. A subgroup of 14 patients was referred to their institution due to persistent pain and weakness after having undergone a structured rehabilitation plan.2 All of the patients in this subgroup were diagnosed with a partial or total lesion of the rotator cuff using MR imaging technique.

Finally, in 1993 Neviaser et al. published the results of 37 patients over the age of 40 years who had been referred to their institution with tearing of the rotator cuff that had not been diagnosed beforehand following anterior primary dislocation.3 These patients were unable to raise their arm after reduction, and could not recover the function after physiotherapy. Due to this, the authors determined that the rotator cuff lesions are consequence of shoulder dislocation. However, all of these studies involved a significant distortion in selection and did not take the possible confusion variables into account.

The chief limitation of this study is therefore that, in spite of having found a high level of correlation between both shoulders, we are unable to determine causality or evaluate the risk of glenohumeral dislocation for the healthy contralateral shoulder. Another limitation is the absence of inter- and intra-observer analysis. Nevertheless, the usual diagnostic process occurs without the shoulder surgeon having a second opportunity to interpret the examination or a second opportunity to reach a conclusion. Another limitation of this study is that the subjects were not monitored for other medical problems such as diabetes or hypercholesterolaemia, or for chronic overloading of the rotator cuff due to their work or sport. These are known risk factors for suffering injury to the rotator cuff, so that this may affect the prevalence of the structural findings, which may amount to a distortion. To resolve these questions appropriate prospective studies would be required that would make it possible to determine causality. As far as we know, this retrospective study is the first one to specifically centre on the prevalence of bilateral tears of the rotator cuffs in patients with unilateral glenohumeral dislocation.

Further studies are required to determine how glenohumeral dislocation contributes to the development of traumatic tears in the rotator cuff. Additionally, for this purpose it would be necessary to have a description of the bilateral structural findings in the rotator cuffs of substantive and representative prospective sample of individuals involved with unilateral shoulder dislocation, to help shoulder surgeons to interpret the clinical usefulness of MR imaging findings. Respecting this, our study evaluated MR imaging alterations in both shoulders in a broad sample of individuals with unilateral symptoms, supply data on the prevalence of all the diseases which were not available in previous studies.

ConclusionOur study found a high degree of correlation with the presence of a posterosuperior rotator cuff injury after glenohumeral dislocation between the shoulder which had suffered the event and the presumably healthy contralateral shoulder. We did not find this same correlation with the subscapularis tendon and the medial dislocation of the biceps. Nevertheless, this work was not able to confirm or rule out causality.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

FundingThis study did not receive any specific grant from public or private financing agencies, or from not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Ethics committee approvalResearch project approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Teaching and Research of the Hospital Británico de Buenos Aires. Registration number: 6128.