Pertrochanteric fractures constitute an important part of the daily activity of the orthopedic surgeon. The aim of this study was to carry out an analysis of pre-, intra- and post-operative radiographic parameters and to analyze the results of stable and unstable intertrochanteric fractures treated with short nails with dynamic distal locking.

Materials and methodsRetrospective study in our center, between the years 2017–2021 of patients over 65 years of age with pertrochanteric fracture. We included 272 patients treated with Gamma3 Nail (Stryker®) with dynamic distal locking. As variables, we recorded: age, medical comorbidities, fracture pattern according to AO/OTA, osteopenia according to Singh's classification, pre-operative (such as diaphyseal extension), intra-operative (such as tip-to-the-apex or medial cortical support) and post-operative radiographic parameters (such as time to consolidation or loss of reduction), pre- and post-operative Barthel, quality of life and complications and reinterventions, such as non-union or cut-out.

ResultsThe mean age was 83.28 years (65–102). Two hundred four cases were women (75%). The average follow-up was 18.2 months (12–24). The distribution according to AO/OTA classification was 85.7% 31.A1; 12.5% 31.A2; 1.9% 31.A3. Radiographic consolidation was obtained in 97.4% of cases. Tip to apex distance was less than 25mm in 95.6% of cases. Medial cortical support was positive or neutral in 88.6% of cases. Sixty cases (22.1%) of screw back-out were recorded. Eight reinterventions (2.9%) were performed, corresponding to three cut-outs (1.1%), three non-unions (1.1%), one avascular necrosis (0.4%) and one secondary hip osteoarthritis (0.4%).

ConclusionsShort nail with dynamic distal locking offers good clinical, radiological and functional results in all types of AO/OTA patterns, without increasing the complication rate, as long as there is an appropriate tip-to-the-apex distance and good medial cortical support.

Las fracturas pertrocantéreas constituyen una parte importante de la actividad diaria del cirujano ortopédico. El objetivo de este estudio fue realizar un análisis de parámetros radiológicos pre, intra y postoperatorios y analizar los resultados de fracturas intertrocantéreas estables e inestables tratadas con clavos cortos con bloqueo distal dinámico.

Materiales y métodosRealizamos un estudio retrospectivo en nuestro centro, entre los años 2017-2021, de pacientes mayores de 65años con fractura pertrocantérea. Se incluyeron 272 pacientes tratados con clavo Gamma3 (Stryker®) con bloqueo distal dinámico. Como variables se registraron: edad, comorbilidades médicas, patrón de fractura según AO/OTA, osteopenia según clasificación de Singh, parámetros radiológicos preoperatorios (como extensión diafisaria), intraoperatorios (como tip-to-the-apex o soporte cortical medial) y postoperatorios (como el tiempo hasta la consolidación o la pérdida de reducción), Barthel pre y postoperatorio, calidad de vida y complicaciones y reintervenciones, como pseudoartrosis o cut-out.

ResultadosLa edad media fue de 83,28años (65-102). 204 casos fueron mujeres (75%). El seguimiento medio fue de 18,2meses (12-24). La distribución según clasificación AO/OTA fue del 85,7% 31.A1; del 12,5% 31.A2, y del 1,9% 31.A3. Se obtuvo consolidación radiográfica en el 97,4% de los casos. La distancia tip-to-the-apex fue inferior a 25mm en el 95,6% de los casos. El soporte cortical medial fue positivo o neutro en el 88,6% de los casos. Se registraron 60 casos (22,1%) de back-out del tornillo cefálico. Se realizaron 8 reintervenciones (2,9%), correspondientes a 3 fenómenos de corte (1,1%), 3 pseudoartrosis (1,1%), una necrosis avascular (0,4%) y una artrosis secundaria de cadera (0,4%).

ConclusionesEl clavo corto con bloqueo distal dinámico ofrece buenos resultados clínicos, radiológicos y funcionales en todo tipo de patrones AO/OTA, sin aumentar la tasa de complicaciones, siempre y cuando exista una distancia tip-to-the-apex adecuada y un buen soporte cortical medial.

Hip fractures are a growing problem in the Western world, due to the aging population.1–8 They are considered a clear consequence of osteoporosis and bone fragility,2,4,6,8–11 a common problem in these patients. It is estimated that the incidence of hip fractures will increase to 6.26 million by 2050.4,7,8,11–15 This is directly related with increasing life expectancy and improved healthcare systems. These fractures pose a significant morbidity and mortality to the patient. Complications can include chronic pain, loss of autonomy and quality of life, and even death.4,7,10,16 In some series, this is as high as 20–30% in the first year.15,17 These fractures imply significant social and economic impact as well, which in some series is estimated at 2.9 billion dollars.1,4,18

Of these, extracapsular fractures account for more than 50% of such fractures.1,6,12,17,19 Different radiographic aspects that could predict the final outcome have been studied. Perhaps the best known: the tip-to-the-apex.9 Regarding treatment, there are numerous therapeutic alternatives, and many studies have been carried out.6,14,15 Most of these treatment options offer good results, good consolidation rates and a low percentage of medical complications,5,6,9,13 although these injuries are usually associated with functional impairment.3,15

To explain the superiority in the use of nails in regards to other devices, trauma surgeons claim the speed of implantation, biomechanical advantages and minimally invasive approach, among other arguments.8,11,12,20 Initially, these devices were associated with a great number of complications at the distal locking level, such as peri-implant fractures.2,12,22–24 However, these complications have been drastically reduced with newer nail designs.2,12,20,22 Distal locking serves to maintain fracture length, increase stability and prevent nail buckling in wide canals1,2,4,6–8,10–12,15 while lag screw allows perpendicular compression of the fracture.16,20,22

Despite this, it remains a priority to identify the fracture pattern, and to try to achieve optimal reduction to ensure the appropriate outcome.3,9,13,23

There are several papers that recommend distal locking depending on the fracture pattern. In the present study, we have performed a dynamic distal lock to all the fractures. The hypothesis is that a controlled dynamization and compression of the fracture offers good results, although it could be at the expense of a slight shortening and the potential risk of malunion. The aim of this study is to carry out an analysis of radiographic parameters, mechanical, clinical and functional results in all types of fractures (stable and unstable) treated with short nail with dynamic distal locking. Do we know everything about pertrochanteric fractures? Could criteria and treatments be unified?

Materials and methodsGroup of patientsAfter approval had been obtained from the ethics committee of our hospital, a retrospective study was performed between 2017 and 2021 in our center. We selected patients over 65 years of age, with a diagnosis of pertrochanteric fracture operated by short Gamma Gamma3 Nail (Stryker®) with dynamic distal locking.

We excluded patients with a follow-up of less than a year, whatever the reason.

MethodAll selected patients were operated with a Gamma Gamma3 (Stryker®) nail, regardless of the type of fracture, with dynamic distal locking. The nails could have an angulation of 120°, 125° or 130°, depending on the anatomical characteristics of the patients. Cephalic screws and distal locking screws were selected with dimensions according to the patient's measurements.

EvaluationIn all patients in the series we assessed:

- •

Demographic variables: age, sex, laterality, history, pre- and post-operative baseline, autonomy and ambulation.

- •

Barthel Scale: Pre-injury and at the end of follow-up.

- •

Fracture classification: Fractures were evaluated by four members of the unit and classified based on the AO/OTA classification. The same four members classified bone quality based on Singh's radiographic classification.

- •

The average time of hospital stay, medical complications during admission, mechanical and functional results were analyzed.

- •

Radiographic parameters: Pre-operative and intra-operative radiographic parameters were analyzed.

- ∘

Pre-operative:

- •

Lateral cortical thickness greater or not than 25mm5,9,19,21

- •

Presence of reverse oblicuity6,9,13,15,19,21

- •

Presence of comminution in lateral wall9,19,21

- •

Presence of comminution on the medial wall6,9,13,15,19,21

- •

Presence of free fragment of the greater trochanter9,19,21

- •

Presence of transverse fracture of the greater trochanter9,19,21

- •

Presence of lesser trochanter fracture with diaphyseal extensión6,9,19,21

- •

- ∘

Intra-operative:

- •

Pin entry point location: anterior, centered or posterior3,10

- •

Cephalic length3

- •

Cephalic obliquity in axial plane: anterior, neutral or posterior3,12

- •

Position of the cephalic in coronal plane: inferior, centered or superior3,10

- •

Tip-to-the-apex distance6,9

- •

Medial cortical support: positive, neutral, or negative3,5

- •

- ∘

- •

During follow-up, average time to consolidation, number of technical aids for ambulation at the end of follow-up, as well as early (before one year) and late (after one year) complications, whether or not they required reintervention, were evaluated in all cases. Variables such as gluteal pain, loss of reduction, pseudarthrosis, implant rupture, back-out, cut-out, cut-in heterotopic calcifications, avascular necrosis, infection or material discomfort were included. Consolidation was considered as full weight-bearing in a patient along with radiographic evidence of bridging callus on radiographs.11,15,17,22 Non-unions was defined as an insufficient healing and callus formation of the fracture in two X-ray projections after 6 months.2,8,11–13,15,17,22 Cut-out was defined as the screw penetrating the joint line and migrating proximally.9,13,17 Back-out was considered as cephalic lateral protrusion ≥5mm in relation to first post-operative X-ray.12,16,17

The SPSS 26.0 package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for data processing and statistical analysis. Descriptive data were obtained for all the variables analyzed This included mean, median, standard deviation and IQR for the quantitative variables. For the qualitative ones, on the other hand, frequencies and percentages were registered. We based the results of our quantitative variables on the mean, as the sample followed a normal distribution. After collecting the data, we compared the different radiographic parameters with the possibility of early failure and need for reintervention. Statistical comparisons were performed using a Chi-Squared test, since our sample follows a normal distribution and we copmared independent cualitative variables. For all statistical tests, p-values<0.05 were considered significant.

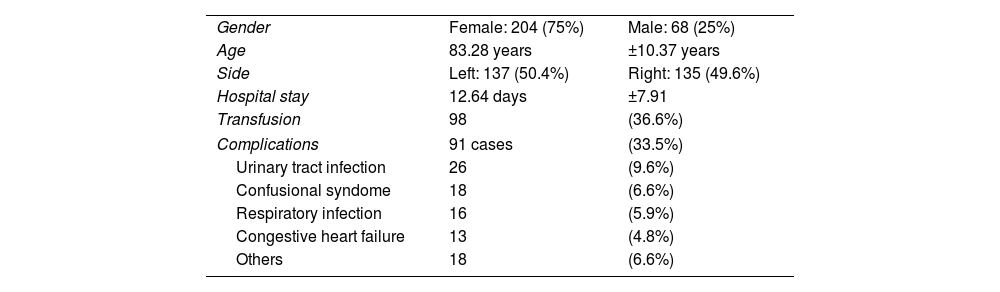

ResultsDemographic and hospital stay dataA total of 272 patients with pertrochanteric fractures, operated with Gamma Gamma3 (Stryker®) short dynamic nail, with at least one year of follow-up, were obtained. The average age was 83.28 years (65–102). Two hundred four cases were women (75%). The average follow-up was 18.2 months (12–24). Prior to fracture, 62.9% were independent for activities of daily living, 31.3% were partially dependent and 5.9% were totally dependent. Prior to fracture, 56.6% walked without technical aids, 30.1% with one technical aid, 12.5% with two technical aids or a walker, and 0.7% were non-ambulatory. The mean pre-fracture Barthel was 84.60 (10–100). Of the patients, 80.9% were not taking previous treatment for osteoporosis, although 23.9% had previously had a fragility fracture.

One hundred thirty-five cases were right femurs (49.6%) compared to 137 left femurs (50.4%). The mean time os hospital stay was 12.64 days (3–63).

Ninety-one cases (33.5%) presented some type of complication during admission. Most notable complications were 26 urinary tract infections (9.6%); 18 confusional syndromes (6.6%); 16 respiratory infections (5.9%) or 13 decompensations of heart failure (4.8%). Ninety-eight cases (36.6%) required blood transfusion prior or after the surgery.

Demographic information, as well as complications, are shown in Table 1.

Demographic data and medical complications.

| Gender | Female: 204 (75%) | Male: 68 (25%) |

| Age | 83.28 years | ±10.37 years |

| Side | Left: 137 (50.4%) | Right: 135 (49.6%) |

| Hospital stay | 12.64 days | ±7.91 |

| Transfusion | 98 | (36.6%) |

| Complications | 91 cases | (33.5%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 26 | (9.6%) |

| Confusional syndome | 18 | (6.6%) |

| Respiratory infection | 16 | (5.9%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 13 | (4.8%) |

| Others | 18 | (6.6%) |

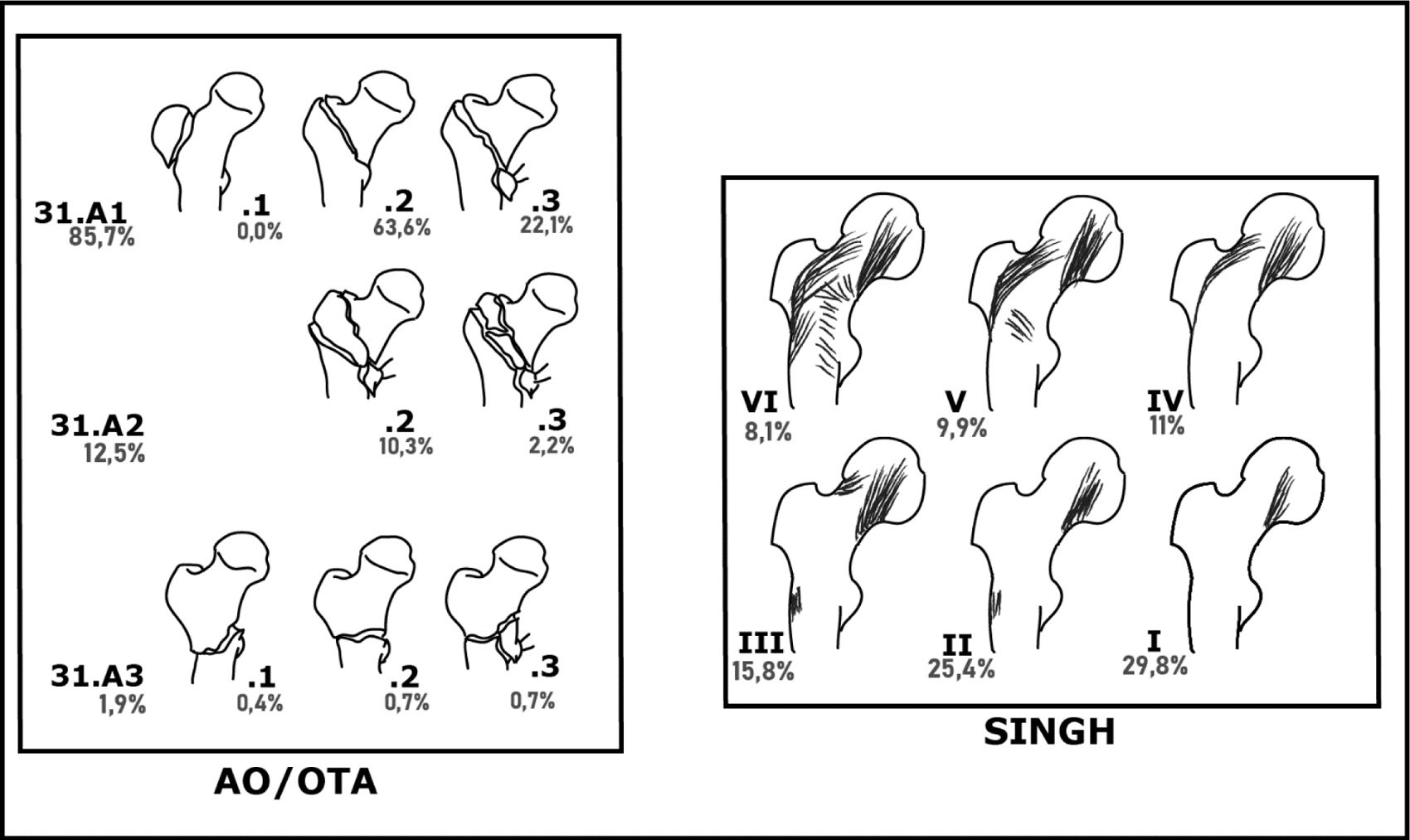

With respect to the AO/OTA classification, 233 cases were obtained in group 31.A1 (85.7%); 34 in 31.A2 (12.5%) and 5 in 31.A3 (1.9%). Based on subtypes, 173 cases of 31.A1.2 (63.6%); 60 cases of 31.A1.3 (22.1%); 28 cases of 31.A2.2 (10.3%); 6 cases of 31.A2.3 (2.2%); 1 case of 31.A3.1 (0.4%); 2 cases of 31.A3.2 (0.7%) and 2 cases of 31.A3.3 (0.7%) were obtained.

Regarding the assessment of bone quality according to Singh's classification, 81 cases of type I (29.8%), 69 cases of type II (25.4%), 43 cases of type III (15.8%), 30 cases of type IV (11%), 27 cases of type V (9.9%) and 22 cases of type VI (8.1%) were obtained.

The distribution of cases according to classifications is shown in Fig. 1.

Pre and intra-operative radiographsAccording to the observers analyzing radiographic criteria of instability, 21 cases (7.7%) of fractures with extension below the lesser trochanter were detected; 74 cases (27.2%) with lateral wall thickness below 25mm; 37 cases (13.6%) with oblique fracture line component; 45 cases (16.5%) with free fragment of the greater trochanter and 30 cases (11%) with free fragment of the lesser trochanter with extension to the diaphysis.

Intraoperatively, the following data was recorded: the entry point at the tip of the greater trochanter was centered in 208 cases (76.5%); posterior in 45 cases (16.5%) and anterior in 19 (7%). In the coronal plane, the cephalic was in the center of the neck in 161 cases (59.2%); inferior in 98 cases (36%) and superior in 13 (4.8%). In the axial projection, the cephalic was centrally located in 188 cases (69.1%), posteriorly in 50 cases (18.4%) and anteriorly in 34 (12.5%). After intra-operative reduction and compression, medial cortical support in the anteroposterior projection was neutral in 175 cases (64.3%); positive in 66 cases (24.3%) and negative in 31 cases (11.4%). The tip-to-apex distance, measured as the sum of the distances from the tip of the screw to the subchondral bone, in the anteroposterior and axial projection, was less than 25mm in 260 cases (95.6%). Only nine intra-operative radiographic complications were recorded (3.3%), consisting of one loss of reduction, which required a new closed reduction, and eight rotations of the cephalic fragment. One of them (0.4%) developed heterotopic ossification. The rest did not present any incidence.

Post-operative dataA total of 265 cases (97.4%) consolidated satisfactorily, in an average time of 3.83 months (2–12). Four cases (1.5%) did not consolidate and required reintervention. In three cases (1.1%) consolidation was not assessable, because the patients suffered an early cut-out, requiring reintervention for arthroplasty within the first two months post-operatively.

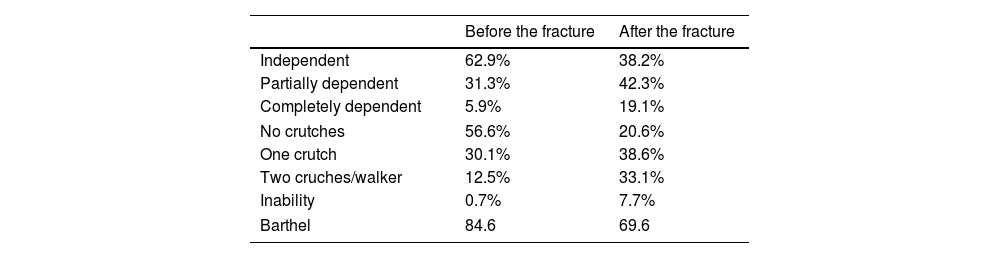

At the end of follow-up, 104 patients (38.2%) were independent, compared to 115 (42.3%) partially dependent and 52 (19.1%) completely dependent. Fifty-six patients (20.6%) were able to ambulate without technical aids; 105 (38.6%) with one technical aid; 90 cases (33.1%) with two technical aids or a walker and 21 cases (7.7%) were no longer ambulatory. Of the total number of patients, 44 (16.2%) presented Trendelemburg type limp at the end of follow-up. The mean Barthel at the end of follow-up was 69.6 (0–100), which represented a loss of 15 points with respect to the initial situation.

The pre-operative and post-operative relationship of the functional parameters is shown in Table 2.

Functional information and ability to walk before and after the fracture.

| Before the fracture | After the fracture | |

|---|---|---|

| Independent | 62.9% | 38.2% |

| Partially dependent | 31.3% | 42.3% |

| Completely dependent | 5.9% | 19.1% |

| No crutches | 56.6% | 20.6% |

| One crutch | 30.1% | 38.6% |

| Two cruches/walker | 12.5% | 33.1% |

| Inability | 0.7% | 7.7% |

| Barthel | 84.6 | 69.6 |

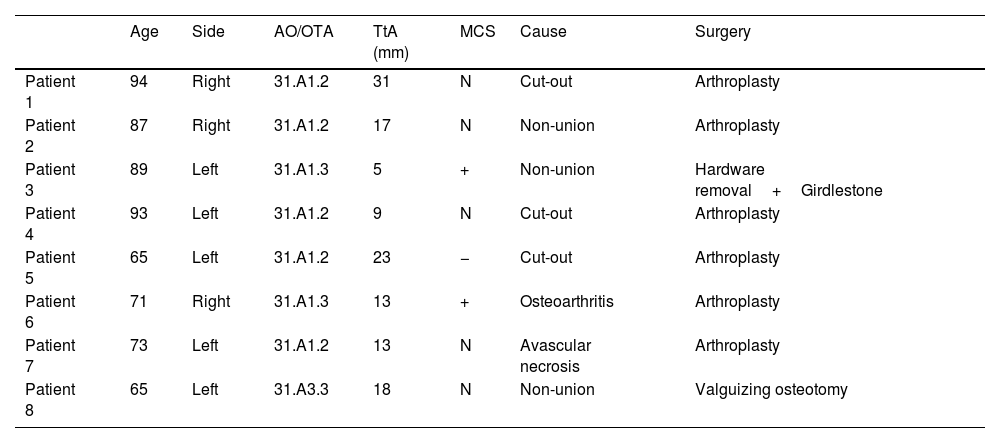

Eight (2.9%) reinterventions were performed during follow-up. Of these, five (1.8%) were performed within the first year of follow-up and three (1.1%) after one year of follow-up. Some of these reinterventions were: three cases (1.1%) of early cut-out, which were reconverted to hip arthroplasty; one case (0.4%) of secondary hip osteoarthritis and one case (0.4%) of avascular necrosis. Both were converted to total hip arthroplasty.

There were four cases (1.5%) of non-union. Of these, one (0.4%) was reconverted to total hip arthroplasty. One patient (0.4%) underwent material removal and Girdlestone resection arthroplasty, due to his baseline situation. One case (0.4%) of non-union with fatigue and material breakage could not be reoperated due to the high anesthetic risk. There was also one case (0.4%) of non-union in which we performed a valguizing osteotomy and new synthesis. The X-rays of this patient are displayed in Fig. 2. Information of the fractures that required reintervention is shown in Table 3.

Male, 65-year old, 31.A3.3 fracture. Smoker (10cigarettes/day). Ex-alcoholic. Ex-drug user. No allergies. HIV infection, pancreas insufficiency, hepatic cirrhosis. Prior surgery for clavicle fracture. He developed an atrophic non-union, which required an desrotatory osteotomy. This patient is currently under follow-up. 1a: Anteroposterior X-ray at Emergency Department. 1b: Axial X-ray at Emergency Department. 2a: Anteroposterior X-ray first day after surgery. 2b: Axial X-ray first day after surgery. 3a: Anteroposterior X-ray at one year follow-up. Varization and non-union can be observed. 3b: Axial X-ray at one year follow-up. Varization and non-union can be observed. 4a: Coronal image of CT-scan at one year follow-up, showing no signs of union. 4b: Sagital image of CT-scan at one year follow-up, showing no signs of union. 5a: Anteroposterior X-ray first day after reintervention. 5b: Axial X-ray first day after reintervention.

Reinterventions.

| Age | Side | AO/OTA | TtA (mm) | MCS | Cause | Surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 94 | Right | 31.A1.2 | 31 | N | Cut-out | Arthroplasty |

| Patient 2 | 87 | Right | 31.A1.2 | 17 | N | Non-union | Arthroplasty |

| Patient 3 | 89 | Left | 31.A1.3 | 5 | + | Non-union | Hardware removal+Girdlestone |

| Patient 4 | 93 | Left | 31.A1.2 | 9 | N | Cut-out | Arthroplasty |

| Patient 5 | 65 | Left | 31.A1.2 | 23 | − | Cut-out | Arthroplasty |

| Patient 6 | 71 | Right | 31.A1.3 | 13 | + | Osteoarthritis | Arthroplasty |

| Patient 7 | 73 | Left | 31.A1.2 | 13 | N | Avascular necrosis | Arthroplasty |

| Patient 8 | 65 | Left | 31.A3.3 | 18 | N | Non-union | Valguizing osteotomy |

TtA: tip to apex (mm); ORIF: open reduction internal fixation; MCS: medial cortical support: positive (+); neutral (N); negative (−).

Other radiographic and clinical findings: 18 cases (6.6%) partial reduction losses were detected, with shortening and varus displacement of the fragment. They had, however, no clinical repercussions and that did not require reintervention. All of them, but two, had dynamized the distal screw position. In the rest of the cases with dynamization of the distal locking screw, no varization of the cephalic fragment was observed. Of those, the medial cortical support was positive in three cases (1.1%), neutral in eight (2.9%) and negative in seven cases (2.6%). The tip-to-the-apex distance was ≥25mm in just one case There were four cases (1.5%) of heterotopic calcifications, which did not require additional management; one case (0.4%) of residual gluteal pain. We registered 60 cases (22.1%) of screw back-out. Nevertheless, none of the required hardware removal.

Comparative analysisNone of the variables analyzed in this work with the Chi-Square statistical test obtained statistical significance. There were no differences when failures and reinterventions were analyzed with respect to fracture patterns according to AO/OTA, Singh classification, pre-operative (such as medial comminution) and intra-operative (such as tip-to-the-apex or medial cortical support) radiographic findings, etc.

The variable that presented the greatest statistical trend was the recorded cases of back-out with respect to the variable “medial cortical support”, with a p=0.099, far from statistical significance.

DiscussionIn this work, we have reviewed our results in 272 pertrochanteric fractures treated with short endomedullary nail and distal dynamic locking. We have analyzed radiogrpahic parameters, both pre and post operative to try help define what makes a fracture of this kind unstable and what can lead to a premature failure. We have reaffirmed the good prognosis of these fractures with these devices, specially when the tip-to-the-apex distance is respected. We have obtained a 97.4% of satisfactory consolidation, with only 2.9% reinterventions performed, most of them (three cases) due to early cut-out of the cephalic screw.

Because of the economic and social impact of pertrochanteric fractures,1,4,7,18 many investigators have sought to better define the criteria for instability of these fractures and the best surgical treatment options. It is the obligation of the orthopedic surgeon to minimize the impact of these injuries and improve patient care.1

Our goal has been to bring together all of these described factors and attempt to analyze our results with short dynamic nails independent of the fracture pattern, and the literature based on them. To the best of our knowledge, there are many papers that individually analyze several of these factors, but not one that unifies them, except perhaps the one by Haidukewych.9

Extra- and intramedullary devices are currently available for the treatment of these fractures. There is consensus on the mechanical superiority of endomedullary devices in the treatment of unstable fractures.7,9,21,23 Endomedullary devices offer greater stiffness and better resist and prevent varus collapse of unstable fractures.7,21

Regarding the length of the endomedullary device, controversy continues to exist.17,24 Classically, the use of longer nails has been recommended in fractures presenting more unstable patterns, 31.A2 and 31.A3 of the AO/OTA.7 Luque et al.17 found no differences in the treatment of 31.A2 fractures between short and long nails in relation to clinical and radiological outcome. However, patients with long nails had statistically significant greater blood loss and need for transfusion. They also found differences in surgical time. Therefore, they recommend the use of short nails in 31.A2 fractures as long as they are distally locked (in their study, all short nail locks were lock in static position).17 Goodnough et al.24 suggest that some surgeons may nevertheless choose to use a long starting nail to avoid a stress zone in the femur, regardless of the fracture stability pattern. For example, Hedge et al.11 analyzed the outcome of distal locks in stable fractures, but systematically used long nails in all cases, even though it was mechanically correct to treat with short nails. In our work, all selected patients were operated with short nails. Retrospectively, most of them presented 31.A1 and 31.A2 AO/OTA fractures without finding a higher failure rate in 31.A2 fractures, similar to what Luque et al.17 suggest. Five cases of 31.A3 fractures were also operated with a short nail, pattern which is not include in other works.1,3,12,17 One of them presented dynamization and varus displacement and developed a non-union, which required reintervention (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, it seems to have a component of biological and not mechanical origin. However, given the small percentage of the series that constitute these fractures, we cannot affirm that 31.A3 fractures can sistematically be treated with short nails. Based on the results we have obtained, we can suggest that short nails can be used more extensively, in many other patterns previously recommended to be treated with long nails, as it does not seem to increase the amount of complications and still has satisfactory consolidation rates. This could prevent complications linked to long nails, such as higher blood loss.

The literature is probably more extensive regarding distal locking of endomedullary devices.1,2,4,6,8,10–16,18,22 The function of distal locking is to maintain length, stabilize rotationally and prevent nail buckling when the intramedullary canal is wide.1,2,4,6,8 Originally, most nails were associated with a high percentage of fractures and complications related to this distal locking, although this has decreased drastically with new designs.2,8,14,15,22 Some authors speak of up to 15% of complications in relation to the distal locking,15 the most common being irritation of the iliotibial band.14 This has led authors to question whether or not it was necessary to lock all fractures in the trochanteric region.1,2,4,6,8,10–12,18,19,22 Most of these works are carried out on stable pertrochanteric fracture patterns. In them, the authors agree that it is not necessary to lock these patterns.2,4,6,8,11,14,15,22 This reduces surgical time, fluoroscopic exposure and minimizes complications.2,4,6,8,14,15 There is, however, a stable pattern configuration that Mori et al.13 warn about the necessity to lock. This is the case of stable patterns where the entry point is too posterior.13 We have found few papers that ask this question in unstable patterns.1,10,12,15 In general, there is consensus on the need for distal locking (although it is not specified whether dynamic or static in many of them) in unstable patterns.1,9,10,15,18,22 Even so, that opinion is not universal, as there are also papers, such as that of Caiaffa et al.12 from 2018 with good results in unlocked unstable patterns. Most of these papers did not include 31.A3 patterns of AO/OTA. Buruian et al.15 even design a distal locking decision algorithm in pertrochanteric fractures. In our center, all nails are locked dinamically hoping to achieve controlled compression of the fracture fragments. This practice is questionable, because several fracture patterns could be left unlocked, minimizing surgical time and costs. Carefully analyze the fracture pattern for primordial, to identify the need or not to block and save unnecessary gestures.

There are also papers that discuss static or dynamic lag screw position.16,20 In our center, we dynamically lock the lag screw to dynamize and compress the fracture. Kuzyk et al.20 carried out biomechanical work where they demonstrated a significant loss (12.4%) of axial and lateral stiffness with dynamic locking, and advised caution and further study with locking in unstable patterns. Later, Hulshof et al.16 conducted a paper in 2022 where they found no differences in outcomes and complications between static or dynamic positioning. They caution, however, that the Gamma3 (Stryker®) design may be inappropriate for true static locking. A dynamic lag screw allows greater back-out, which Skála-Rosenbaum22 and Ciaffa et al.12 translated into interfragmentary compression. Ciaffa et al.12 registered back-out of the cephalic screw in all their cases. However, the average protrussion distance was higher in the unstable patterns. This results match those of Hulshof et al.16 and Skála-Rosenbaum et al.22 In our work we detected 60 cases of screw back-out (22.1%), matching the results previously shown by other authors. This can be explained by the dynamic position to allow fracture compressionn. This may seem a low percentage, despite the fact that all lag screw locks were dynamic. This is probably due to good intra-operative reduction, adequate medial cortical support and the stability of the fractures themselves.

In general, all studies report good consolidation rates. It is estimated that, despite the age and baseline circumstances of these patients, more than 90% consolidate satisfactorily.2,4,8,11,12,15–18 Some authors suggest that a distal static locking slows, but does not prevent, consolidation.19 The main reason for these good consolidation results lies in the abundant amount of cancellous bone and good vascularization.15 Our results in this regard are similar to those obtained in the literature, as we had 97.4% consolidation. We could not identify any common factor in those cases that did not consolidate.

One of the most classically cited radiographic feature has been the tip-to-apex distance.9 It applies to both intra- and extramedullary devices.9 A distance of less than 25mm is predictive of good outcome, and minimizes the risk of cut-out.9 Recently, however, other concepts have been introduced, such as medial cortical support in reduction.3,5 Chang et al.3 introduced this concept in 2015. It is as important to try to aim for positive medial cortical balance as it is to try to avoid negative balance. This work served to demonstrate that a nonanatomic reduction could nevertheless offer advantages in fracture prognosis. Adequate anteromedial cortical support can convert unstable patterns into stable ones.5 Subsequently, this same author in 20175 published a correlation of fluoroscopic reduction with CT reconstructions. The work served to corroborate previous studies and reaffirm that a negative balance is a predictor of reduction loss and higher failure rate. In our work we have analyzed these two measures, among other radiographic parameters. 95.6% of our sample had a tip to apex distance of less than 25mm. Likewise, positive or neutral medial cortical support was achieved in 88.6%, while it was negative in only 11.4%. Of the latter, only one required reintervention, so we found no relationship with implant failure in our sample. These appropriate intra-operative and post-operative radiographic measurements may justify the good results obtained and the low percentage of complications and reinterventions in our sample.

One of the most feared complications is cut-out, estimated at around 2% in the literature.2,4,6,12,16,17,19 Since these are usually geriatric patients, most authors recommend reconversion to hip arthroplasty, although there is also the possibility of reosteosynthesis.12 Other complications can be non-union (<2%),2,4,8,11,12,15–19 peri-implant fractures (1–3%)2,6,12,15,18,23,24 or reduction losses (1–3%).4,12,19 The overall revision rate ranges from 0.5 to 2.8%.4,12,16,17,19 Our results match those of the literature, as we obtained 1.1% cut-out and 1.5% non-union rate. All of these, slightly lower than the literature. We had, however, a higher percentage of reduction loss, with 6.6%, usually with fracture shortening. Of those, the medial cortical support was positive in three cases (1.1%), neutral in eight (2.9%) and negative in seven cases (2.6%). The tip-to-the-apex distance was ≥25mm in just one case. Our reoperation rate was 3.3%.

This work has several limitations. Firstly, its retrospective nature with its inherent limitations. Secondly, the sample size, although respectable, did not present a sufficient number of complications and reinterventions to be able to obtain statistical significance of the variables analyzed. It is possible that the appropriate application of principles previously described in the literature is responsible for the satisfactory results. Thirdly, no validated clinical scales were used in the post-operative period and follow-up. Forthly, not many cases of pattern AO/OTA 31.A3 were registered, therefore the use of short nails cannot be generalized in this pattern.

ConclusionsThe short nail with dynamic distal locking offers satisfactory clinical, radiological and functional results and sufficient stability for the different pertrochanteric fracture patterns of AO/OTA. We have not recorded an increase in complications or failures with this implant configuration. However, we have not had enough cases of AO/OTA 31.A3 to record enough data about this certain pattern to generalize the use of short nails in these cases.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical considerationsThe authors’ response to the ethical responsibilities required by the publisher is reflected below.

Protection of people and animalsN/A. The authors declare that no experiments have been carried out on humans or animals for this research.

Data confidentialityN/A. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentN/A. The authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

FundingThe authors declare that they do not present any type of financing or relationship that may have influenced the results reported in this scientific document.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interest.