The purpose of this study is to evaluate the clinical outcomes and complications of percutaneous achilles tendon repair with absorbable sutures.

Material and methodsA prospective cohort study including patients treated for an achilles tendon rupture from January 2016 to March 2019 was conducted.

Inclusion criteria≥18 years of age, non-insertional (2–8cm proximal to insertion) achilles tendon ruptures. Open or partial ruptures were excluded. The diagnosis was based on clinical criteria and confirmed by ultrasonography in all patients. Epidemiological data, rupture and healing risk factors, previous diagnosis of tendinopathy, pre-rupture sport activity, job information, mechanism of rupture and the time in days between lesion and surgery were collected.

Patients were assessed using visual analogue scale (VAS) at the 1, 3, 6 and 12-month follow-up. The achilles tendon rupture score (ATRS) were assessed at the 6 and 12 month follow-up. Ultrasound was performed at the 6-month follow-up. The re-rupture rate and postoperative complications were also collected.

ConclusionsIn our experience, percutaneous achilles tendon repair with absorbable sutures in patients with an acute achilles tendon rupture has shown good functional results but with a high incidence of complications. Although most complications were transitory sural nerve symptoms, this complication would be avoided in patients treated conservatively. For this reason, conservative treatment associated with an early weightbearing rehabilitation protocol should be considered a viable option for patients with achilles tendon ruptures, mainly in cooperative young patients.

El propósito de este estudio es evaluar los resultados clínicos y las complicaciones de la reparación percutánea del tendón de Aquiles con suturas reabsorbibles.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio de cohorte prospectivo que incluye pacientes tratados por una rotura del tendón de Aquiles desde enero de 2016 hasta marzo de 2019.

Criterios de inclusión≥18años de edad, roturas del tendón de Aquiles no insercionales (de 2 a 8cm proximales a la inserción). Se excluyeron roturas abiertas o parciales. El diagnóstico se basó en criterios clínicos y se confirmó mediante ecografía en todos los pacientes. Se recogieron datos epidemiológicos, factores de riesgo de rotura y cicatrización, diagnóstico previo de tendinopatía, actividad deportiva previa a la rotura, información laboral, mecanismo de rotura y tiempo en días entre la lesión y la cirugía.

Los pacientes fueron evaluados utilizando la escala analógica visual (VAS) en el seguimiento de 1, 3, 6 y 12meses. La puntuación de rotura del tendón de Aquiles (ATRS) se evaluó a los 6 y 12meses de seguimiento. La ecografía se realizó a los 6meses de seguimiento. También se recogieron la tasa de re-ruptura y las complicaciones postoperatorias.

ConclusionesEn nuestra experiencia, la reparación percutánea del tendón de Aquiles con suturas reabsorbibles en pacientes con rotura aguda del tendón de Aquiles ha mostrado buenos resultados funcionales pero con una alta incidencia de complicaciones. Aunque la mayoría de las complicaciones fueron síntomas transitorios del nervio sural, esta complicación se evitaría en pacientes tratados de forma conservadora. Por esta razón, el tratamiento conservador asociado a un protocolo de rehabilitación con carga temprana debe considerarse una opción viable para pacientes con roturas del tendón de Aquiles, principalmente en pacientes jóvenes colaboradores.

The achilles tendon accounts for 20% of all large tendon injuries1 with an estimated incidence ranging from 11 to 37 per 100,000.2,3 Controversy still surrounds what the optimal treatment for achilles tendon ruptures is. Detractors of conservative treatment argue that this option leads to a greater risk of a re-rupture when compared to surgical treatment.4 However, this argument has recently been questioned based on results obtained from accelerated functional rehabilitation protocols for conservative treatment.5

Regarding surgical treatment, several techniques have been proposed being percutaneous achilles tendon repair first described in 1977 by Ma and Griffith.6 The main limitation of that technique is the potential risk of sural nerve injury secondary to entrapment with an incidence rate in clinical studies of around 13%.7 Some authors have reported higher re-rupture rates with the percutaneous technique when compared to open, but it remains controversial.8 Another important issue for the percutaneous technique is the use of non-absorbable vs. absorbable sutures. With the aim of reducing the incidence of complications related to non-absorbable suture intolerance, absorbable sutures have been used with no differences in re-rupture rates.9

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the clinical outcomes and complications of percutaneous achilles tendon repair with absorbable sutures.

Material and methodsA prospective cohort study including patients treated for an achilles tendon rupture from January 2016 to March 2019 was conducted. This study was done in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, under the Ethics’ committee approval. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Inclusion criteria: ≥18 years of age, non-insertional (2–8cm proximal to insertion) achilles tendon ruptures. Open or partial ruptures were excluded.

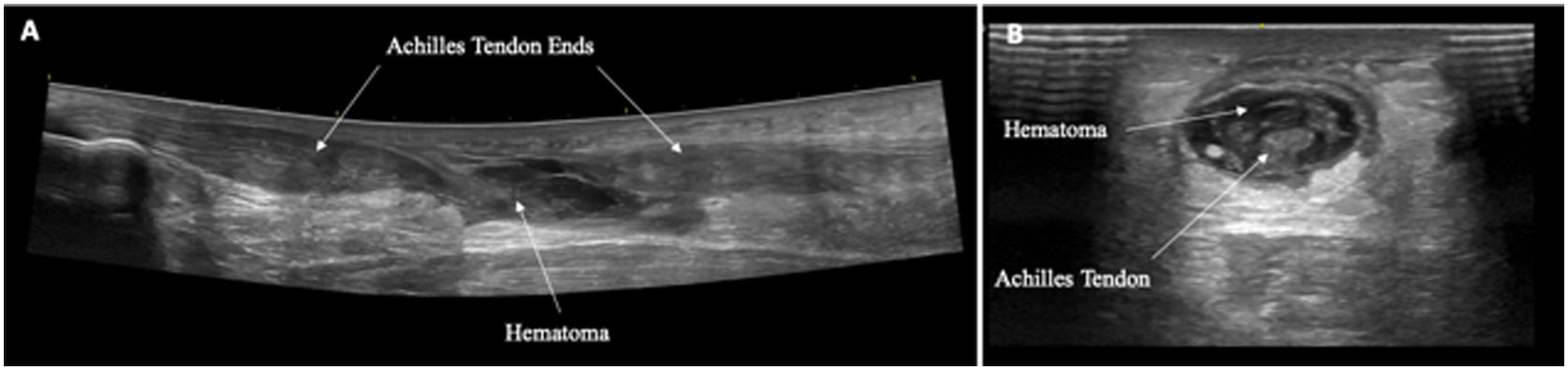

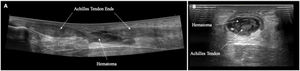

The diagnosis was based on clinical criteria (palpable gap over the tendon, positive Thompson's test and functional impairment) and confirmed by ultrasonography in all patients (Fig. 1A and B).

Epidemiological data (age and sex), rupture and healing risk factors (smoke, hypertension, diabetes or chronic steroid treatment), previous diagnosis of tendinopathy (confirmed by MRI or ultrasound), pre-rupture sport activity (mild=once-twice per week; moderate=3–4 times per week; intensive=>4 times per week), job information (sedentary or physical), mechanism of rupture (sport, traumatic or casual) and the time in days between lesion and surgery were collected.

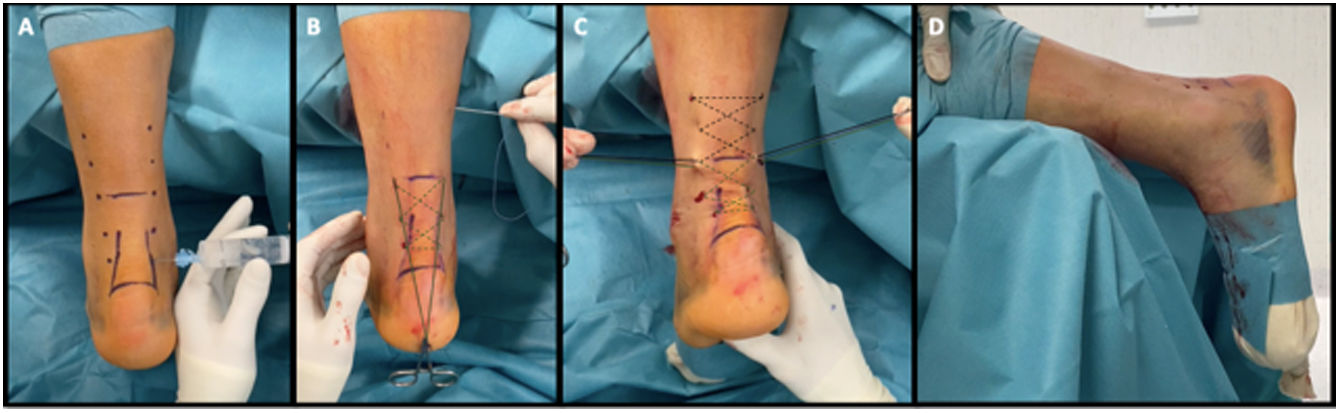

Surgical techniqueThe surgery was performed within 7 days after rupture in all patients. Patients were positioned in the prone position with the injured foot hanging freely over the edge of the table. The rupture location had been previously marked.

No tourniquet was used and local anaesthesia with 15–20mL of Mepivacaine 2% was applied through the 10 puncture holes that were later used for needle entry.

At each site of needle entrance, a small longitudinal incision was made with a number 11 blade so that the needle could pass without entrapment of subcutaneous tissue.

The tendon was then repaired with the modified repair Bunnell configuration (Fig. 2A–D), using Vicryl (polyglactin) No. 1 (Ethicon, Inc.) being the ends of the sutures were harvested and tied medially and laterally at the height of the rupture, maintaining the ankle in 20° of plantar flexion. Afterwards, a clamp was used to ensure that subcutaneous tissue was not entrapped with the suture. Small incisions were closed with steri-strip or exceptionally fine sutures. A sterile dressing and cast were applied with the ankle in 20° of plantar flexion.

Postoperative careThe cast was removed 7–10 days after surgery. A functional orthosis with three heel wedges was put in place and partial weightbearing allowed. Afterwards, one wedge was removed every week allowing weightbearing with a functional orthosis at 90° angle 4 weeks after surgery. The functional orthosis was removed 6 weeks post-surgery.

Functional rehabilitation initiated 2 weeks after surgery being careful with excessive dorsal flexion. A strengthening and proprioceptive exercise programme proceeded 6–8 weeks after surgery. Non-impact sport was introduced after the removal of the functional orthosis and impact sports was not permitted before 6 months after surgery.

AssessmentPatients were assessed using visual analogue scale (VAS) at the 1, 3, 6 and 12-month follow-up. The achilles tendon rupture score (ATRS) were assessed at the 6 and 12 month follow-up. Ultrasound was performed at the 6-month follow-up. The re-rupture rate and postoperative complications were also collected.

Statistical analysisThe baseline characteristics were summarized using standard descriptive statistics, and a descriptive analysis was carried out. Continuous variables are described as mean (SD) and categorical data are summarized as absolute frequency and percentages.

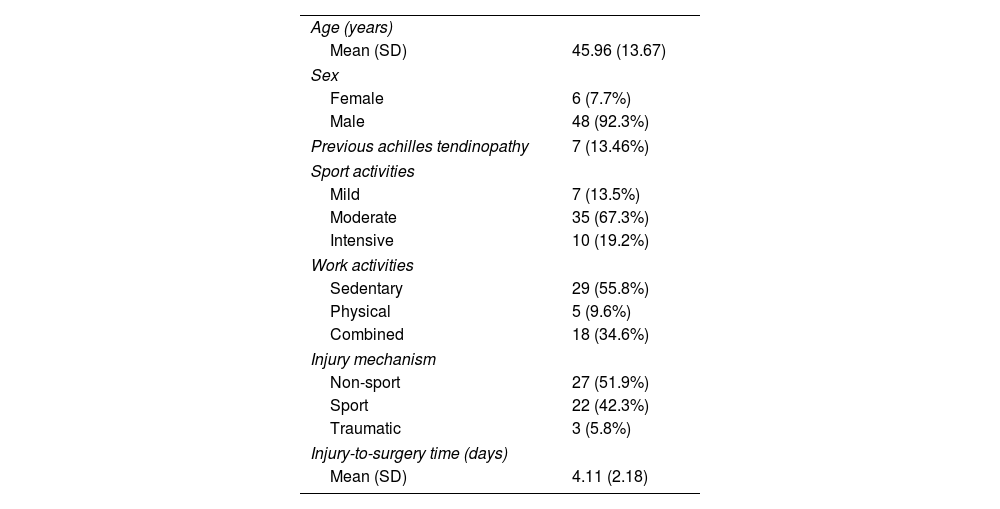

ResultsFifty-two achilles tendon ruptures of 52 patients were included. The mean (SD) age was 45.96 years (13.67) and there were 48 men (92.3%) and 6 women (7.7%).

A previous diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy was present in 7 patients (13.5%).

Seven patients (13.5%) referred to participation in no sports or mild sports, 35 patients (67.3%) in moderate sports and 10 patients (19.2%) in intensive sports.

A total of 29 patients (55.8%) referred to perform sedentary work, 5 patients (9.6%) intensive physical work while 18 patients combined both sedentary and physical work.

Aetiology of the rupture was a non-sportive mechanism in 27 patients (51.9%), a sport injury in 22 cases (42.3%) and a traumatic mechanism was identified in 3 patients (5.8%). The mean time (SD) between injury and surgical treatment was 4.11 days (2.18) with a maximum of 7 days and a minimum of 1 day (Table 1).

Patient baseline characteristics (n=52).

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 45.96 (13.67) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 6 (7.7%) |

| Male | 48 (92.3%) |

| Previous achilles tendinopathy | 7 (13.46%) |

| Sport activities | |

| Mild | 7 (13.5%) |

| Moderate | 35 (67.3%) |

| Intensive | 10 (19.2%) |

| Work activities | |

| Sedentary | 29 (55.8%) |

| Physical | 5 (9.6%) |

| Combined | 18 (34.6%) |

| Injury mechanism | |

| Non-sport | 27 (51.9%) |

| Sport | 22 (42.3%) |

| Traumatic | 3 (5.8%) |

| Injury-to-surgery time (days) | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.11 (2.18) |

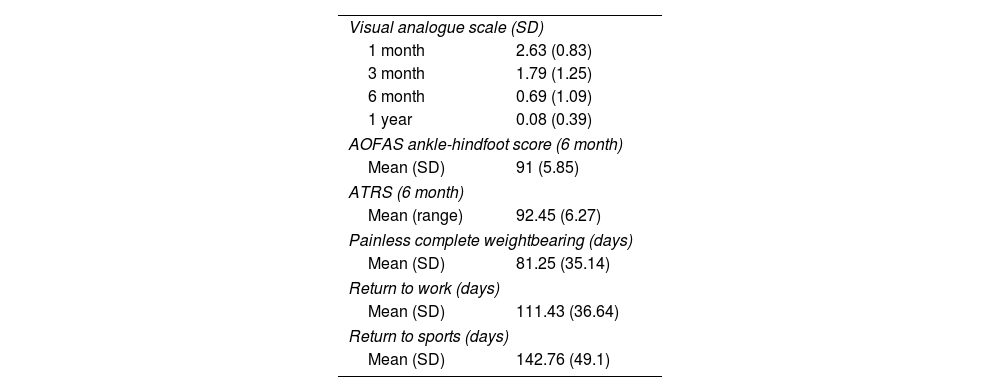

The results of VAS scoring (SD) at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months follow-up were 2.63 (0.83), 1.79 (1.25), 0.69 (1.09) and 0.08 (0.39) respectively. Mean (SD) ATRS score was 92.45 points at 6 months (6.27) and 94.04 points at 12 months follow up (4.59).

In ultrasound study at 6-month follow-up good thickness and hypoechoic thickening without hypervascularization in the Doppler study was observed in all patients.

The mean time (SD) to full-weightbearing without pain was 81.25 days (35.14). At that time, basic daily activities (excluding sport and work activities) were restarted. The mean time (SD) to return to work and sport activities was 111.43 days (36.64) and 142.76 days (49.1), respectively. All of 47 patients (90.4%) confirmed having returned to their previous level of sports activity after surgery (Table 2).

Outcomes of the percutaneous achilles tendon repairs.

| Visual analogue scale (SD) | |

| 1 month | 2.63 (0.83) |

| 3 month | 1.79 (1.25) |

| 6 month | 0.69 (1.09) |

| 1 year | 0.08 (0.39) |

| AOFAS ankle-hindfoot score (6 month) | |

| Mean (SD) | 91 (5.85) |

| ATRS (6 month) | |

| Mean (range) | 92.45 (6.27) |

| Painless complete weightbearing (days) | |

| Mean (SD) | 81.25 (35.14) |

| Return to work (days) | |

| Mean (SD) | 111.43 (36.64) |

| Return to sports (days) | |

| Mean (SD) | 142.76 (49.1) |

ATRS: achilles tendon rupture score.

There were 3 re-ruptures (5.77%) with a mean time between surgery and re-rupture of 108.75 days (SD 28.4) all of them within 4-month follow-up. The mechanism of re-rupture was a non-sports rupture in all patients. No rupture at the time to return to sports activity was reported.

The 13 complications (25%) reported include 3 re-ruptures, previously described, 1 superficial wound infection and 9 transitory sural nerve injuries. All sural nerve injuries were transitory and had a mean (SD) time until their resolution of 73.3 days (37.1). The symptoms related to the sural nerve injury were resolved within 150 days in all patients (Table 3).

DiscussionThe present study shows good functional outcomes for percutaneous achilles tendon repair with absorbable suture in patients with an acute achilles tendon rupture, but not exempt of minor complications.

As for the epidemiological data, the mean age is 45.96 years old, 92.3% men, being most ruptures related to sport injuries (42.3%), according to the previously reported.2,10,11

According to the literature, the achilles tendon rupture affected the area between 2 and 8cm proximal to the calcaneal insertion in all of our patients, corresponding to hypovascularized zone.12

We use a double Bunnell crossed type suture according to the results observed in biomechanical studies13 and absorbable Vicryl #1 suture instead of PDS for many reasons. First, PDS is smoother. It has a greater risk of cutting the tendon during knot-pulling.14 Moreover, absorbable sutures are associated with a lower incidence of suture reaction and have shown no difference in regard to the functional results.14 Furthermore, the vicryl material suffers greater degradation, which contributes to relief from the complications associated with sural nerve injuries when they happen.

Progressive improvement in the VAS score was achieved, with a mean score of 2.63 at the 1-month follow-up and 0.08 at the 12-month follow-up. The percentage of patients with no pain at 3, 6 and 12 months was 17%, 69%, and 96%, respectively, with the greatest improvement in the VAS score between the 3 and 6-month follow-up, similar to previously reported.15 ATRS scores at 6 and 12 months were 92.45 and 94.04, respectively with better results achieved at the 6-month follow-up comparing to previously reported.16 An explanation for the difference in functional scores at 6 months follow-up might be the mean age of our patients, with only 7 (13.5%) patients older than 60 in this series.

The 90% of our patients reported having returned to their pre-injury level, increasing to 98% when we exclude re-rupture patients. One the 3 patients with a postoperative tendon re-rupture, recovered the previous level of activity.

One of the most important aspects regarding achilles tendon rupture treatment is the re-rupture incidence. In this study a re-rupture rate of 5.77% (N=3) was observed, which is similar to the previously reported (2%–8% re-rupture rates) for percutaneous achilles tendon repair.17 Classically, the percutaneous repair re-rupture rate was seen to be lower when compared to the initial conservative treatment.4,6 The main problem associated with this classical conservative treatment was the prolonged time of immobilization, which entailed important secondary muscle atrophy.18 After the early weightbearing and controlled rehabilitation protocol, the re-rupture rate with conservative treatment decreased drastically.5,19 Due to the favourable results in some recent studies with conservative treatment and because of the bimodal age distribution of achilles tendon ruptures, some authors advocate for conservative treatment for young patients. This is because there is the potential for tendon healing in this younger age-range. It might be worthwhile to reserve surgical treatment for patients in the second-peak group. For that purpose, prospective studies between conservative and surgical treatment comparing the incidence between the two peaks are necessary.

It is important to empathize that in this series 1 in 4 patients (25%) suffered some type of complication. This rate is higher than those previously reported for percutaneous achilles tendon repair, which has been established between 4 and 15%.16 A reason which would explain this fact is that we have observed a high rate of complications due to transitory sural nerve injuries symptoms (17.3%), complication which, if is transitory, is not considered as surgical complication in most previous studies. These sural nerve injuries were completely resolved in all cases within 4 months after surgery. One of the main causes of sural nerve injuries is the entrapment during the percutaneous suture.16 The use of the absorbable suture, which has the same biomechanical properties as the non-absorbable suture and with fewer reported side effects, could explain the disappearance of symptoms in these patients.19

Finally, related to complications, one case of superficial wound infection was observed and completely resolve with oral antibiotic treatment.

Our study has some limitations. First, this a prospective cohort study and there is no control group with conservative treatment. Moreover, despite achilles tendon rupture have a bimodal age distribution with different aetiologies described, all the patients were included in a single group due to the small number of patients over 60 years of age.

In conclusion, in our experience, percutaneous achilles tendon repair with absorbable sutures in patients with an acute achilles tendon rupture has shown good functional results but with a high incidence of complications. Although most complications were transitory sural nerve symptoms, this complication would be avoided in patients treated conservatively.20 For this reason, conservative treatment associated with an early weightbearing rehabilitation protocol should be considered a viable option for patients with achilles tendon ruptures, mainly in cooperative young patients.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence II.

FundingThe authors declare that they have not received financial funding to carry out the research and/or the preparation of the article.

Conflicts of interestAll authors declare no conflicts of interest.