To evaluate peri-prosthetic femoral fractures by analysing type of patient, treatment and outcomes, and to compare them with Spanish series published in the last 20 years.

Material and methodsA retrospective review of the medical records of patients with peri-prosthetic femoral fractures treated in our hospital from 2010 to 2014, and telephone survey on the current status.

ResultsA total of 34 peri-prosthetic femoral fractures were analysed, 20 in hip arthroplasty and 14 in knee arthroplasty. The mean age of the patients was 79.9 years, and 91% had previous comorbidity, with up to 36% having at least 3 prior systemic diseases. Mean hospital stay was 8.7 days, and was higher in surgically-treated than in conservative-treated patients. The majority (60.6%) of patients had complications, and mortality was 18%. Functional status was not regained in 61.5% of patients, and pain was higher in hip than in knee arthroplasty.

DiscussionPeri-prosthetic femoral fractures are increasing in frequency. This is due to the increasing number of arthroplasties performed and also to the increasing age of these patients. Treatment of these fractures is complex because of the presence of an arthroplasty component, low bone quality, and comorbidity of the patients.

ConclusionPeri-prosthetic femoral fractures impair quality of life. They need individualised treatment, and have frequent complications and mortality.

Evaluar las fracturas periprotésicas de fémur analizando las características de los pacientes, el tipo de tratamiento y los resultados, y compararlas con las series españolas publicadas en los últimos 20 años.

Material y métodoEvaluación retrospectiva de las fracturas periprotésicas de fémur atendidas en nuestro centro entre 2010 y 2014. Revisión de las historias clínicas y encuesta telefónica sobre la situación actual.

ResultadosHemos analizado 34 fracturas periprotésicas de fémur, 20 sobre prótesis de cadera y 14 sobre prótesis de rodilla. La edad media fue 79,9 años. El 91% tenían comorbilidad previa y hasta un 36% tenían al menos 3 enfermedades sistémicas previas. La estancia hospitalaria media fue 8,7 días, mayor en los casos tratados quirúrgicamente. Hasta el 60,6% de los pacientes presentaron complicaciones y la tasa de mortalidad ha sido del 18%. El 61,5% de los pacientes no recuperaron el estado funcional previo a la fractura, con mayor dolor en los pacientes con artroplastia de cadera.

DiscusiónLas fracturas periprotésicas de fémur son cada vez más frecuentes, porque cada vez se realizan más artroplastias y en pacientes más mayores. El tratamiento es complejo, porque a la propia dificultad de la fractura se añade la presencia de un implante previo, la baja calidad ósea y la comorbilidad.

ConclusionesLas fracturas periprotésicas de fémur suponen una merma en la calidad de vida de los pacientes. Requieren un tratamiento individualizado. La tasa de complicaciones y de mortalidad es muy elevada.

Peri-prosthetic femoral fractures are increasingly common due to the increasing number of arthroplasties being performed in older patients, which also results in a greater number of revision arthroscopies that in turn carry a greater risk of peri-prosthetic fracture.1,2 Depending on the series, the incidence of peri-prosthetic femoral fracture around total hip arthroplasty or revision arthroplasties varies between 0.3% and 18%.2–4 An incidence has been described of supracondylar femoral fractures varying between 0.3% and 2.5%, increasing to 1.6–38% in revision arthroplasties.3–10

Treatment of these fractures is complex and highly challenging because, in addition to the difficulty of the fracture itself, there are the disadvantages of a prior implant which affects the treatment, the poor bone quality of these patients and frequent comorbidity.1,5 In some cases, depending on the patient's general condition and the type of fracture, the treatment of choice is conservative, although most cases require surgical treatment. In peri-prosthetic hip fractures various elements can be used for osteosynthesis (plates, screws, cerclages) and/or a revision stem (short or long), with the use or otherwise of different types of graft. The decision regarding treatment for hip fractures is usually based on the Vancouver classification system.11–13 Supracondylar femoral fractures around a total knee prosthesis can be osteosynthesised by intramedullary nailing or osteosynthesis with a plate. Depending on the type of fracture and the condition of the prosthesis, the prosthesis could be changed for a tumoral prosthesis or a revision prosthesis, and the use of various types of bone graft could be considered.1,5,14

Peri-prosthetic fractures are a serious complication and generally have poor outcomes, a reoperation rate of 7–23%, a complication rate that in some series exceeds 50%, and a very high mortality rate.5,15 Peri-prosthetic femoral fractures have a devastating effect on the patient's quality of life, they pose a therapeutic challenge and also have an extremely high financial cost.5,16

The objective of this study was to assess the cases of peri-prosthetic femoral fractures treated in our centre and to analyse the type of patients that suffer these fractures, the treatment given and the outcomes achieved and compare them with Spanish series published over the last 20 years.

MethodsA retrospective, observational and longitudinal study of the 34 peri-prosthetic femoral fractures (in 33 patients) attended in our centre between 2010 and 2014. Fractures produced intraoperatively were rejected.

The data analysed were taken from the patients’ clinical history. The epidemiological characteristics, previous comorbidity, the time between the arthroplasty and developing the fracture, the type of arthroplasty around which the fracture occurred, the treatment given (and if necessary, the type of osteosynthesis used), the days of hospital stay and whether the patients required a blood transfusion were noted. The treatment given to each of the patients was decided from the clinical session study of each of the fractures and each patient, the surgeon in charge making the definitive decision in each case, taking into account the observations from the clinical session. The data pertaining to follow-up were gathered, any complications that occurred, the fracture consolidation time, reoperations, whether there was a death and how long after the fracture, the time from discharge and the follow-up time. The functional status before the fracture was noted and the functional status after the fracture (the functional status) was classified into 5 subtypes: (1) bed-bound, (2) using a wheelchair, (3) walking with a frame or with 2 crutches, (4) walking with a stick or a crutch, and (5) walking unaided. All the patients who were alive at the time the study was performed were given a telephone survey (which the patients themselves completed or a family member if the patient was not in a condition to speak on the telephone or hold a conversation). The telephone survey completed the data regarding the pre and post fracture functional status which did not appear in the clinical history, and data regarding pain and degree of satisfaction with the treatment were also gathered.

Statistical analysisThe data was handled anonymously and confidentially, and gathered on a database created using Microsoft Excel 2010. IBM SPSS Statistics 22 was used for the statistical analysis. This comprised a descriptive analysis of the variables, calculating the distribution of frequencies for the qualitative variables and the arithmetic mean, and the standard error of the mean for the quantitative variables. The values obtained for the different parameters studied between the group of subjects treated surgically and the group of subjects treated orthopedically were compared using the Student's t-test two-tail (quantitative variables) or with the Chi squared test (qualitative variables), and these 2 tests were also used to compare the group of peri-prosthetic knee fractures and the group of peri-prosthetic hip fractures. The functional status before and after the peri-prosthetic fracture was compared using the Student's t-test for paired samples.

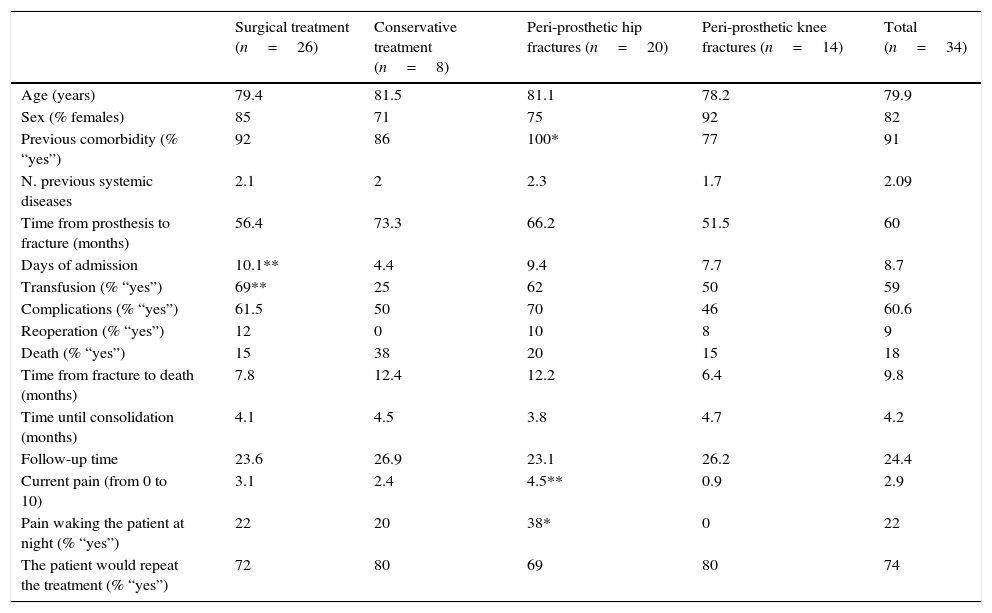

ResultsWe analysed 34 peri-prosthetic femoral fractures in 33 patients (27 females and 6 males), 20 around a hip prosthesis and 14 around a knee prosthesis. Of the knee prostheses around which the fractures occurred, 12 were primary knee arthroplasties and 2 revision arthroplasties; of the hip prostheses, 12 were primary total hip arthroplasties, 7 partial hip arthroplasties (with cemented stem) and one revision total hip arthroplasty. All the peri-prosthetic knee fractures were supracondylar. The peri-prosthetic hip fractures were classified according to the Vancouver system (the classification made on admission and used to decide the treatment was noted): 2 type AL fractures, 2 type AG, 6 type B1, 8 type B2 and 2 type C. No type B3 peri-prosthetic hip fractures were treated. Table 1 shows the differentiated data according to the treatment given (surgical or conservative) and the site of the initial prosthesis (hip or knee).

Outcomes according to treatment (surgical/orthopaedic) and site of the initial fracture (hip/knee).

| Surgical treatment (n=26) | Conservative treatment (n=8) | Peri-prosthetic hip fractures (n=20) | Peri-prosthetic knee fractures (n=14) | Total (n=34) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 79.4 | 81.5 | 81.1 | 78.2 | 79.9 |

| Sex (% females) | 85 | 71 | 75 | 92 | 82 |

| Previous comorbidity (% “yes”) | 92 | 86 | 100* | 77 | 91 |

| N. previous systemic diseases | 2.1 | 2 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 2.09 |

| Time from prosthesis to fracture (months) | 56.4 | 73.3 | 66.2 | 51.5 | 60 |

| Days of admission | 10.1** | 4.4 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 8.7 |

| Transfusion (% “yes”) | 69** | 25 | 62 | 50 | 59 |

| Complications (% “yes”) | 61.5 | 50 | 70 | 46 | 60.6 |

| Reoperation (% “yes”) | 12 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 9 |

| Death (% “yes”) | 15 | 38 | 20 | 15 | 18 |

| Time from fracture to death (months) | 7.8 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 6.4 | 9.8 |

| Time until consolidation (months) | 4.1 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 4.7 | 4.2 |

| Follow-up time | 23.6 | 26.9 | 23.1 | 26.2 | 24.4 |

| Current pain (from 0 to 10) | 3.1 | 2.4 | 4.5** | 0.9 | 2.9 |

| Pain waking the patient at night (% “yes”) | 22 | 20 | 38* | 0 | 22 |

| The patient would repeat the treatment (% “yes”) | 72 | 80 | 69 | 80 | 74 |

Statistically significant difference * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01) surgical vs. conservative or hip vs. knee.

The mean age at which the fracture occurred was 79.9 (range 61–93) years. On average, the fracture occurred 60 months after the arthroplasty (range 4 days to 14 years), the mean age at which the arthroscopy was performed being 74.1 (range 57–84) years. Ninety-one percent of the patients had a prior comorbidity and up to 36% had at least 3 previous systemic diseases. Seventy-six percent had high blood pressure, 36% dyslipidaemia, 27% diabetes mellitus, and 18% heart disease of some type.

26 cases (76.5%) underwent surgery and 8 (23.5%) were treated conservatively. Of the 14 supracondylar peri-prosthetic knee fractures, 4 (28.6%) were treated orthopedically and 10 (71.4%) surgically. The surgical treatment chosen was osteosynthesis with a retrograde intramedullary nail in 7 cases and osteosynthesis with plate in the other 3 cases. Of the 20 peri-prosthetic hip fractures, 4 (20%) were treated conservatively (one type AG, 2 type B1 – subsequently one was rescued with surgical treatment with cerclages due to subsidence of the stem – and one type B2). The other 16 (80%) peri-prosthetic hip fractures were treated surgically from the start: the 2 type AL fractures were osteosynthesised with cerclages; in one type AG fracture the greater trochanter was reinserted using a suture; one type B1 fracture was osteosynthesised with cerclages and in another case underwent osteosynthesis with plate and cerclages, the stem was changed and cerclages placed in another 2 cases; in most of the 7 type B2 fractures that were treated surgically a change of stem and cerclages was chosen (6 cases) and osteosynthesis with plate in only one case; the 2 type C fractures were treated surgically, one was osteosynthesised with a plate and cerclages and the stem was changed for a longer one in the other case. The mean overall hospital stay was 8.7 days, and was significantly longer (p<0.01) in the patients treated surgically than in the orthopaedic patients (10.1 vs. 4.4, Table 1). Fifty-nine percent of the patients required blood transfusion in the days after the fracture or the operation; blood loss in the patients treated surgically was significantly greater (p<0.05), as only 25% of the patients who were treated conservatively needed a blood transfusion and up to 69% of the operated patients required at least one blood transfusion (Table 1).

Up to 60.6% of the patients presented complications. Thirty-five percent of the complications were mild (dysmetria, delayed consolidation, resolved neuritis of the EPS, etc.) and 65% were serious complications (dislocation of the prosthesis – 2 cases, infection – 4 cases, pseudoarthrosis – 3 cases, loosening of the prosthetic parts – 3 cases, refracture, etc.). Complications occurred in 50% of the patients treated orthopedically and in 61.5% of those treated surgically. Despite the high number of complications, only 3 patients required reoperation (one twice and the other on 3 occasions) and one of the patients treated orthopedically developed a pseudoarthrosis and had to be operated subsequently. The mortality rate was 18%, and the deaths occurred on average at 9.8 months after the fracture (range 3 days to 3 years), with a mean age of death of 88.5 (range 81–94) years. Of the 6 patients who died, 3 died in the first month after their fracture (one was the patient who suffered 2 peri-prosthetic fractures 3 months apart, one in each femur and died 11 days after the second fracture) and the other 3 died at least one year after the fracture. Death was not statistically significantly associated with either the treatment used (surgical or conservative) or the site of the initial fracture (hip or knee) (Table 1).

Consolidation was visible on X-ray in 67.7% (23 cases) of the patients, with a mean of 4.2 (range 2–15) months. Of the remaining patients in whom consolidation was not visible on X-ray, 4 died before consolidation could be observed, another 4 patients stopped attending the monitoring visits (and no consolidation was visible on the last X-ray available), and another 3 cases were in follow-up but developed a pseudoarthrosis. Of all the patients, only 15 (45%) were discharged an average of 13.3 (range 3–29) months after their fracture. Mean follow-up was 24.4 (range 0–60) months (including the patients who died within the first post-operative month). If we exclude the 3 patients who died in the first postoperative month, the mean follow-up of the remaining 31 fractures was 26.7 (range 4–60) months.

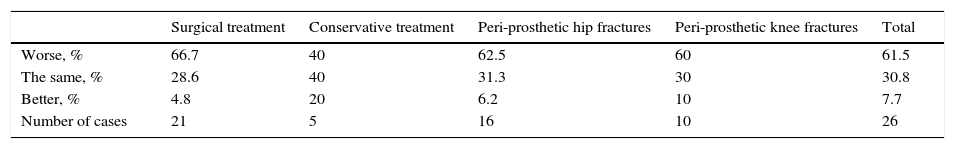

The 27 patients who were alive at the time the study was performed were given a telephone survey. Twenty-three patients responded to the survey (85.2%), and it was not possible to locate the other 4 (14.8%). The telephone survey completed the data on functional status before and after the fracture for the patients whose clinical history did not included this. Functional status significantly worsened as a consequence of the peri-prosthetic fracture (p=0.001), although this worsening had no statistically significant association with the treatment used (surgical or conservative) or the site of the initial fracture (hip or knee) (Table 2). A deterioration in functional status was observed in 61.5% of the patients (the patients who died were not taken into account, with no specific functional status data – 6 patients). Thirty point eight percent of the patients recovered the functional status they had before the fracture and 7.7% had better functional status after treatment of the peri-prosthetic fracture than they had before the fracture (these 2 patients sustained a peri-prosthetic fracture when they were on the waiting list for a change due to loosening of their prosthesis).

Change in the patients’ functional status after peri-prosthetic femoral fracture.

| Surgical treatment | Conservative treatment | Peri-prosthetic hip fractures | Peri-prosthetic knee fractures | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worse, % | 66.7 | 40 | 62.5 | 60 | 61.5 |

| The same, % | 28.6 | 40 | 31.3 | 30 | 30.8 |

| Better, % | 4.8 | 20 | 6.2 | 10 | 7.7 |

| Number of cases | 21 | 5 | 16 | 10 | 26 |

Furthermore, the survey provided data on pain and satisfaction. On a scale of 0 to 10, the patients rated their pain as 2.9 (range 0–8). The patients treated for a peri-prosthetic hip fracture experienced more pain than those who had suffered a peri-prosthetic knee fracture (4.5 vs. 0.9; p<0.01, Table 1). Five patients were woken at night by their pain; all of them had a peri-prosthetic hip fracture. Seventy-four percent of the patients were satisfied with the treatment of their fracture and the outcome achieved.

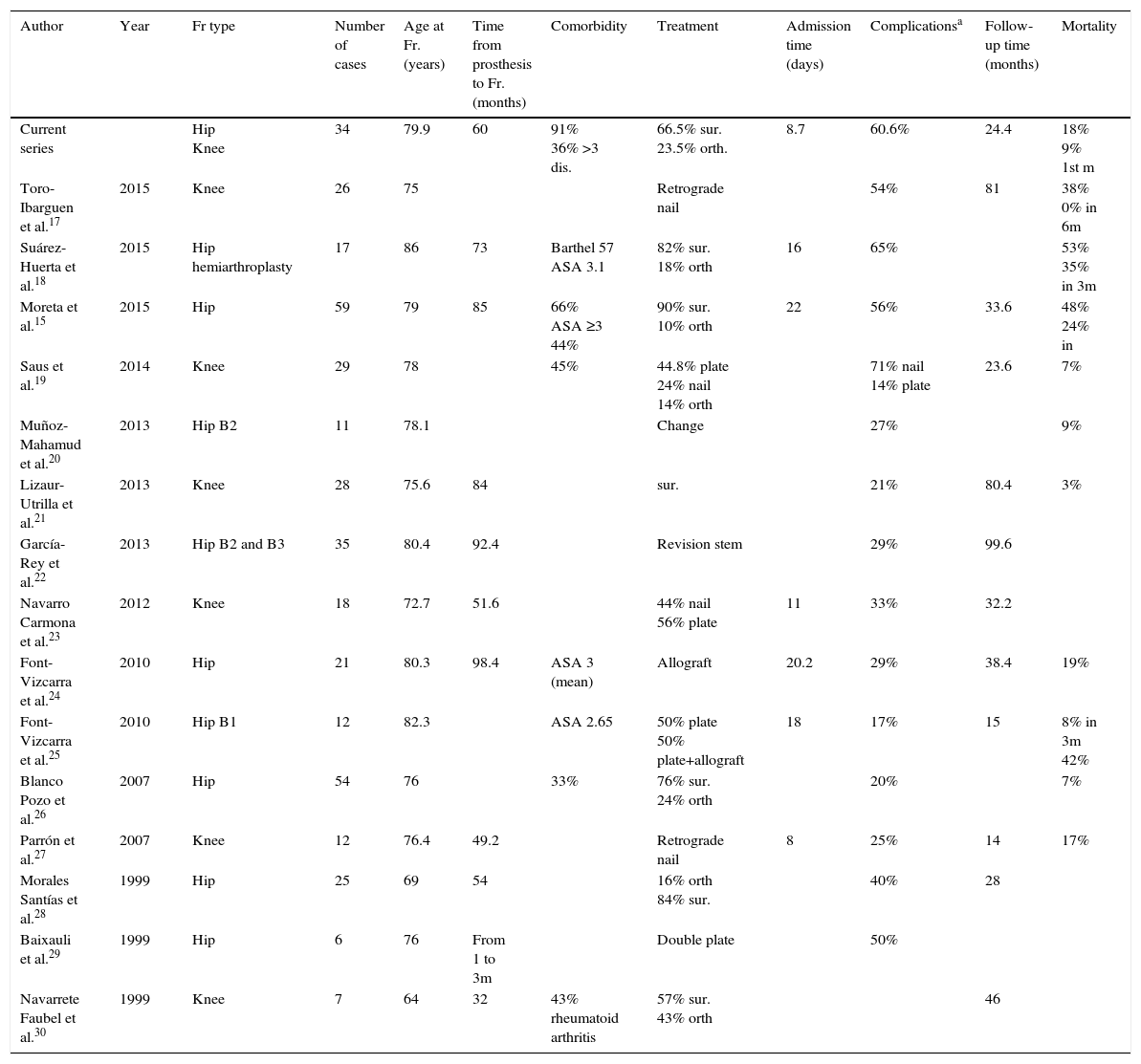

DiscussionMany reviews have been carried out in recent year on peri-prosthetic knee and hip fractures1,2,5,13 and numerous series analysing aspects of the surgical technique, predisposing factors, fracture classification, financial aspects, etc.,3,11,12,14–30 but there is still no consensus on the best way to approach them, and the outcomes presented are average or poor in most series. The data obtained in Spanish series in the last 20 years are shown in Table 3 and will serve as a reference when comparing those achieved in this series.

Series on peri-prosthetic fracture in Spain published in the past 20 years.

| Author | Year | Fr type | Number of cases | Age at Fr. (years) | Time from prosthesis to Fr. (months) | Comorbidity | Treatment | Admission time (days) | Complicationsa | Follow-up time (months) | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current series | Hip Knee | 34 | 79.9 | 60 | 91% 36% >3 dis. | 66.5% sur. 23.5% orth. | 8.7 | 60.6% | 24.4 | 18% 9% 1st m | |

| Toro-Ibarguen et al.17 | 2015 | Knee | 26 | 75 | Retrograde nail | 54% | 81 | 38% 0% in 6m | |||

| Suárez-Huerta et al.18 | 2015 | Hip hemiarthroplasty | 17 | 86 | 73 | Barthel 57 ASA 3.1 | 82% sur. 18% orth | 16 | 65% | 53% 35% in 3m | |

| Moreta et al.15 | 2015 | Hip | 59 | 79 | 85 | 66% ASA ≥3 44% | 90% sur. 10% orth | 22 | 56% | 33.6 | 48% 24% in |

| Saus et al.19 | 2014 | Knee | 29 | 78 | 45% | 44.8% plate 24% nail 14% orth | 71% nail 14% plate | 23.6 | 7% | ||

| Muñoz-Mahamud et al.20 | 2013 | Hip B2 | 11 | 78.1 | Change | 27% | 9% | ||||

| Lizaur-Utrilla et al.21 | 2013 | Knee | 28 | 75.6 | 84 | sur. | 21% | 80.4 | 3% | ||

| García-Rey et al.22 | 2013 | Hip B2 and B3 | 35 | 80.4 | 92.4 | Revision stem | 29% | 99.6 | |||

| Navarro Carmona et al.23 | 2012 | Knee | 18 | 72.7 | 51.6 | 44% nail 56% plate | 11 | 33% | 32.2 | ||

| Font-Vizcarra et al.24 | 2010 | Hip | 21 | 80.3 | 98.4 | ASA 3 (mean) | Allograft | 20.2 | 29% | 38.4 | 19% |

| Font-Vizcarra et al.25 | 2010 | Hip B1 | 12 | 82.3 | ASA 2.65 | 50% plate 50% plate+allograft | 18 | 17% | 15 | 8% in 3m 42% | |

| Blanco Pozo et al.26 | 2007 | Hip | 54 | 76 | 33% | 76% sur. 24% orth | 20% | 7% | |||

| Parrón et al.27 | 2007 | Knee | 12 | 76.4 | 49.2 | Retrograde nail | 8 | 25% | 14 | 17% | |

| Morales Santías et al.28 | 1999 | Hip | 25 | 69 | 54 | 16% orth 84% sur. | 40% | 28 | |||

| Baixauli et al.29 | 1999 | Hip | 6 | 76 | From 1 to 3m | Double plate | 50% | ||||

| Navarrete Faubel et al.30 | 1999 | Knee | 7 | 64 | 32 | 43% rheumatoid arthritis | 57% sur. 43% orth | 46 |

y: years; dis: diseases; Fr: fracture; m: months; orth: orthopaedic; sur.: surgical.

The mean age at which our patients sustained the fracture was 79.9 years, which is within the range described in the literature,15,17–27 and it occurred at an average of 60 months after arthroplasty, which is a rather shorter time than that presented in recent Spanish series.15,17,18,21,22,24 Numerous risk factors which predispose to peri-prosthetic femoral fracture have been described1,2 and, as in other published series,15,18,19,24 we found a very high percentage of comorbidity. Although the classification of the fractures should theoretically determine the treatment of choice, this decision is very often affected by comorbidity, as some patients cannot be operated due to their general condition or comorbidity.1,5,11,12 Ninety-one percent of our patients presented a comorbidity and up to 36% had up to 3 systemic diseases, which doubtless affected the choice of treatment in some cases and is a factor which should be taken into account when evaluating outcomes. Studies, although they use different measurement methods (ASA scale,15,18,24,25 Barthel's scale,18 count of concomitant diseases or risk factors,15,19,26 etc.), agree in that the patients who present peri-prosthetic femoral fractures are elderly and have important previous pathology. Treatment is complex, depends on the type of fracture, the experience and preferences of the surgical team and the condition of the patient,1,5,11–14 which is clearly reflected in our series, using different surgical treatment options. Although in our series the admission time is short compared to others,15,18,24,25 these fractures logically require significantly longer hospital stays for patients who are to undergo surgery compared to those managed conservatively, as can be seen in this study.

Peri-prosthetic fractures and their treatment represent a major traumatic insult for the patient. (59% of transfusions; 70% in operated patients), and they also have poor outcomes, and a high number of complications.5,15 It is difficult to compare some series with others (Table 3), because some authors only record major complications, others do not include patients who die in the days after the fracture in their series (because they do not meet the follow-up time or treatment type criteria) and others only focus on a particular type of complication. All the authors agree that the rate of complications is high (between 17% and 71%; 60.6% in our series), as is mortality (between 3% and 58%; 18% in our series). We should point out that although mortality is high, the average age of the patients who died was 88.5 years and therefore, although we consider that the fracture could have been a destabilising factor, the patients’ diseases and general condition are very relevant.

We have observed a reduction in the functional capacity of patients in 61.5% of cases; or in other words, after the fracture and the treatment, only 38.5% of the patients recovered at least the functional status that they had before they incurred the fracture, which is in line with that observed by other authors.18 Furthermore, the patients continued to experience pain months afterwards (mean score of 2.9 out of 10), and furthermore the pain was enough to wake them at night in up to 22% of patients. It is striking that the patients who presented a peri-prosthetic femoral fracture around a hip prosthesis had significantly more pain than those who suffered the fracture around a knee prosthesis, and also the pain woke them at night more frequently. We found no factor in our series or in the literature to explain this difference in pain, but we consider that it should be taken into consideration in future studies.

Despite all the difficulties that we have described and the objectively poor outcomes achieved, 74% of our patients state that they are satisfied with the treatment received, and if they had the choice would repeat the same treatment, therefore although we should continue to seek better solutions, patients are aware of the seriousness of their illness and “assess us” as a consequence.

This study presents the limitations inherent in a retrospective study, especially in terms of data collection, as well as the heterogeneous group of the fracture type and the treatment given and has a relatively small number of cases since, although on the increase, peri-prosthetic fractures are not very common.

ConclusionsPeri-prosthetic femoral fractures around knee and hip arthroplasty can be considered a single disease, as they are a problematic pair in a similar group of patients. Peri-prosthetic femoral fractures require individualised treatment, meticulous preoperative planning and challenging surgery. The rate of complications and mortality is very high and approximately 2 thirds of patients are not able to recover their previous functional capacity. All of this represents a challenge for surgeons, suffering for the patient and their family, and a high cost to society.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that neither human nor animal testing have been carried out under this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have complied with their work centre protocols for the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patients’ data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gracia-Ochoa M, Miranda I, Orenga S, Hurtado-Oliver V, Sendra F, Roselló-Añón A. Fracturas periprotésicas de fémur sobre prótesis de cadera y rodilla. Análisis de una serie de 34 casos y revisión de las series españolas en los últimos 20 años. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:271–278.