To report the clinical–functional outcomes of the treatment of humeral distal fractures with a total elbow prosthesis.

Material and methodsThis retrospective study was performed in two surgical centres. A total of 23 patients were included, with a mean age of 79 years, and of which 21 were women. The inclusion criteria were: patients with humeral distal fractures, operated on using a Coonrad–Morrey prosthesis, and with a follow-up of more than one year.

According to AO classification, 15 fractures were type C3, 7 C2 and 1 A2.

All patients were operated on without de-insertion of the extensor mechanism.

The mean follow-up was 40 months.

ResultsFlexor-extension was 123–17°, with a total mobility arc of 106° (80% of the contralateral side). Pain, according to a visual analogue scale was 1. The Mayo elbow performance index (MEPI) was 83 points. Excellent results were obtained in 8 patients, good in 13, medium in 1, and poor in 1. The mean DASH (disability) score was 24 points.

ConclusionTreatment of humeral distal fractures with total elbow arthroplasty could be a good treatment option, but indications must be limited to patients with complex fractures, poor bone quality, with osteoporosis and low functional demands. In younger patients, the use is limited to serious cases where there is no other treatment option.

Level of EvidenceLevel of Evidence IV.

Reportar los resultados clínico-radiológicos del tratamiento de las fracturas del húmero distal (FHD) con prótesis total de codo.

Material y métodosEste trabajo retrospectivo fue realizado en 2 centros quirúrgicos. Se incluyeron: pacientes con FHD, operados con prótesis total de Coonrad-Morrey y con seguimiento >1año. Se incluyeron 23pacientes. Veintiuno de los pacientes eran mujeres con una edad promedio de 79años.

Según la clasificación AO, las fracturas eran: 15 del tipo C3, 7 del tipo C2 y una A2.

Todos los pacientes fueron operados sin desinserción del aparato extensor.

El seguimiento promedio fue de 40meses.

ResultadosLa flexoextensión fue de 123–17°, con un arco de movilidad de 106° (un 80% con respecto al lado sano). El dolor según EVA fue de un punto. El SCM promedio fue de 83puntos: 8pacientes tuvieron resultados excelentes, 13buenos, uno regular y otro malo. El DASH promedio fue de 24puntos.

No se evidenciaron aflojamientos en 15pacientes. Se observaron 10complicaciones: 2desgastes del polietileno, un desensamble protésico, 3parestesias postoperatorias del nervio cubital, una necrosis de piel que necesitó un colgajo braquial, 2aflojamientos protésicos, y una falsa vía intraoperatoria.

ConclusionesEl tratamiento de FHD con prótesis total de codo puede ofrecer una opción razonable de tratamiento, pero las indicaciones deben estar limitadas a fracturas complejas donde la fijación interna puede ser precaria, en pacientes con osteoporosis y con baja demanda funcional. En pacientes jóvenes la utilización está limitada a casos graves donde no exista otra opción de tratamiento.

Nivel de evidenciaNivel de evidencia IV.

Distal humeral fractures (DHF) are rare injuries1,2 that usually occur in elderly women.3,4 The number of such fractures has increased over recent decades. Palvanen et al. reported an increase in them of 11/10,000 in 1970 to 30/10,000 in 1995, above all in patients older than 80 years old, and with a tendency to increase.5

In this age group poor bone quality plays a major role when deciding on the best treatment. The results of osteosynthesis are variable, although it has a high number of complications.2,6 In young patients the indication of prosthesis is restricted to those cases when there is no other option for treatment.

Several authors have reported good results using total elbow arthroplasty.7–16

The aim of this work is to report on the clinical–radiological results of a series of patients with DHF treated using total elbow arthroplasty.

Material and methodsA retrospective study was undertaken in 2 surgical centres. The inclusion criteria were: patients with DHF operated using the Coonrad–Morrey total prosthesis (Zimmer®, Warsaw, IN, USA), with a time between trauma and surgery of <2 months and a follow-up >1 year. Pathological fractures were excluded.

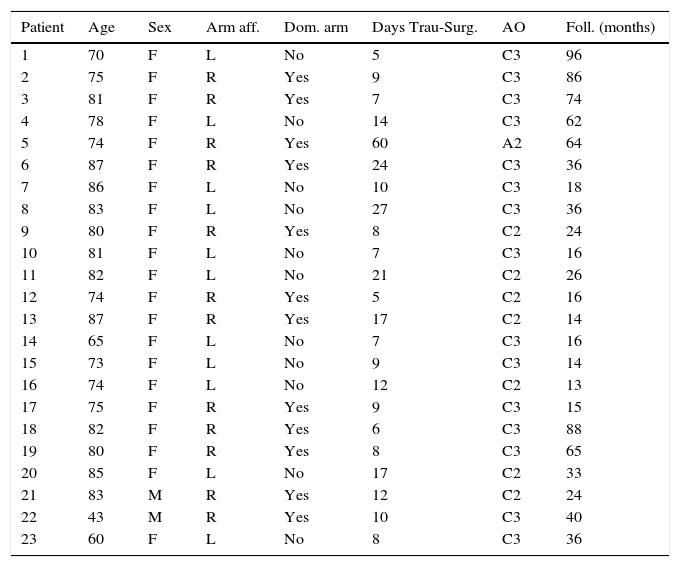

No patient was lost to follow-up. Two patients died in the year after their surgery and they were excluded. 23 patients were included, of which 21 were women and 2 were men, with an average age at the moment of trauma of 76 years (ranging from 43 to 87 years). The right arm was involved in 12 cases and the left arm in 11, and corresponded to the dominant limb in 12 of these cases.

All of the patients were studied using frontal and profile X-rays, and computerised axial tomography was used in the case of intra-articular fractures. According to the AO17 classification, 15 fractures were of the C3 type, 7 of the C2 type and one was A2. The average time from the trauma to surgery was 14 days (ranging from 5 to 60 days) (Table 1).

Demographic data.

| Patient | Age | Sex | Arm aff. | Dom. arm | Days Trau-Surg. | AO | Foll. (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 | F | L | No | 5 | C3 | 96 |

| 2 | 75 | F | R | Yes | 9 | C3 | 86 |

| 3 | 81 | F | R | Yes | 7 | C3 | 74 |

| 4 | 78 | F | L | No | 14 | C3 | 62 |

| 5 | 74 | F | R | Yes | 60 | A2 | 64 |

| 6 | 87 | F | R | Yes | 24 | C3 | 36 |

| 7 | 86 | F | L | No | 10 | C3 | 18 |

| 8 | 83 | F | L | No | 27 | C3 | 36 |

| 9 | 80 | F | R | Yes | 8 | C2 | 24 |

| 10 | 81 | F | L | No | 7 | C3 | 16 |

| 11 | 82 | F | L | No | 21 | C2 | 26 |

| 12 | 74 | F | R | Yes | 5 | C2 | 16 |

| 13 | 87 | F | R | Yes | 17 | C2 | 14 |

| 14 | 65 | F | L | No | 7 | C3 | 16 |

| 15 | 73 | F | L | No | 9 | C3 | 14 |

| 16 | 74 | F | L | No | 12 | C2 | 13 |

| 17 | 75 | F | R | Yes | 9 | C3 | 15 |

| 18 | 82 | F | R | Yes | 6 | C3 | 88 |

| 19 | 80 | F | R | Yes | 8 | C3 | 65 |

| 20 | 85 | F | L | No | 17 | C2 | 33 |

| 21 | 83 | M | R | Yes | 12 | C2 | 24 |

| 22 | 43 | M | R | Yes | 10 | C3 | 40 |

| 23 | 60 | F | L | No | 8 | C3 | 36 |

AO, AO classification; Aff. arm, affected arm; Dom. arm, dominant arm; Foll., follow-up; Trau-Surg., trauma-surgery.

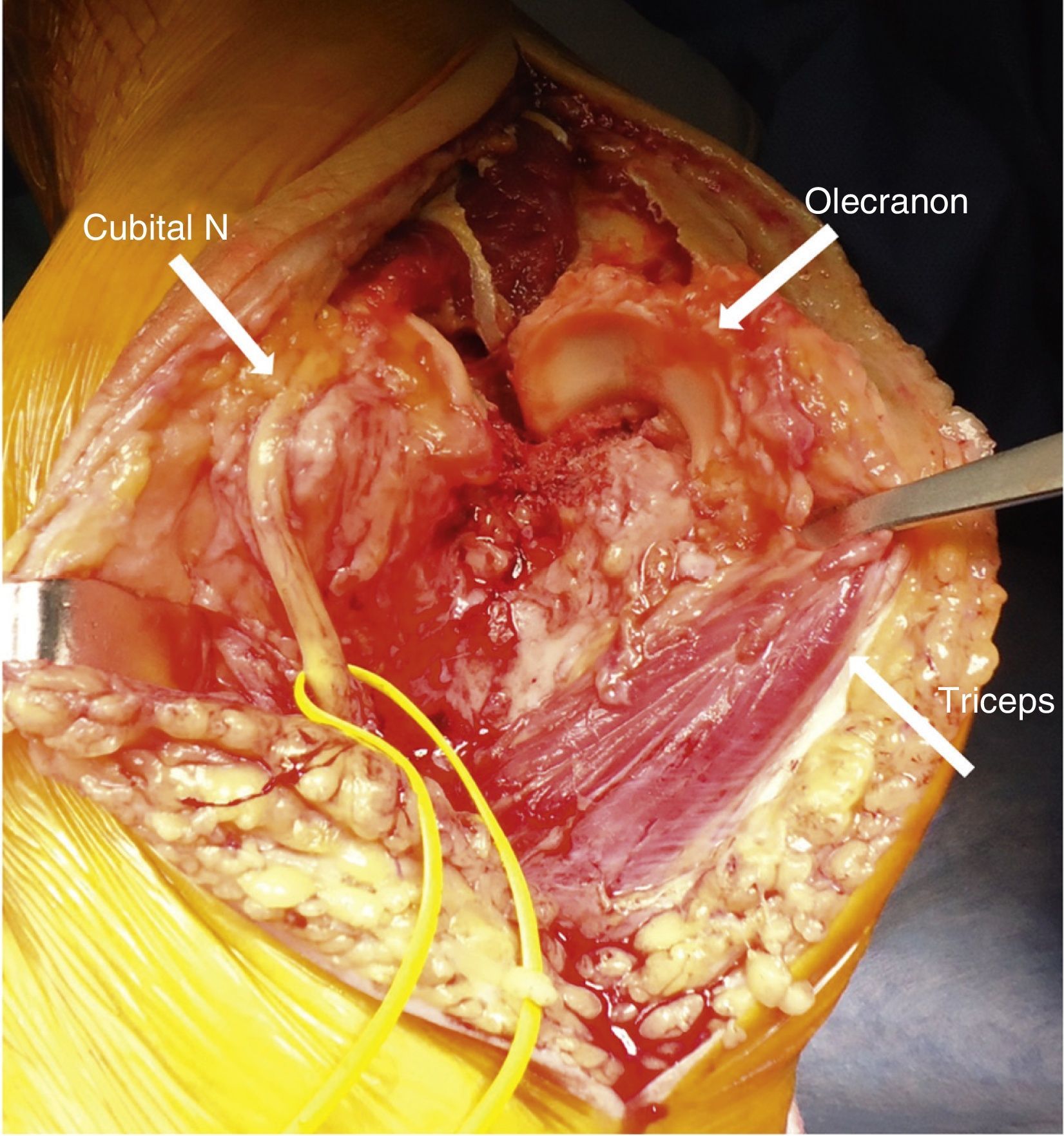

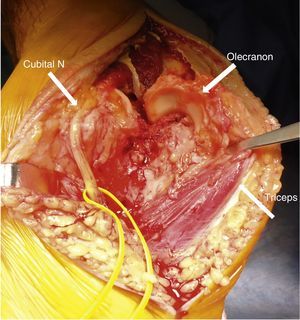

Under local anaesthesia and in dorsal decubitus the affected arm is placed over the thorax of the patient and a pad is placed under the scapula. An incision of approximately 15cm is made in the back of the elbow, centring on the end of the olecranon. The medial edge of the triceps and the cubital nerve are identified and protected during the whole procedure. The articulation is exposed through a posterior approach, luxating the olecranon laterally and exposing the fracture (Fig. 1). The bone fragments of the distal humerus are completely resected.

To prepare the cubital component the canal is entered at the level of the coronoid apophosis with a 4.5mm bit at 45° to the cubital diaphysis. The end of the olecranon is then resected to make it possible to insert the rasps and files parallel to the medullar canal of the cubitus until the test component is able to enter. This must be inserted until its proximal end is at an equal distance between the end of the resected olecranon and the point of the coronoid apophysis.

The medullar canal of the humerus is then prepared. A bit is inserted at the level of the ceiling of the olecranon fossa and it is rasped until the test component is able to enter. Due to the absence of the humeral epiphysis it is not necessary to use the cutting template.

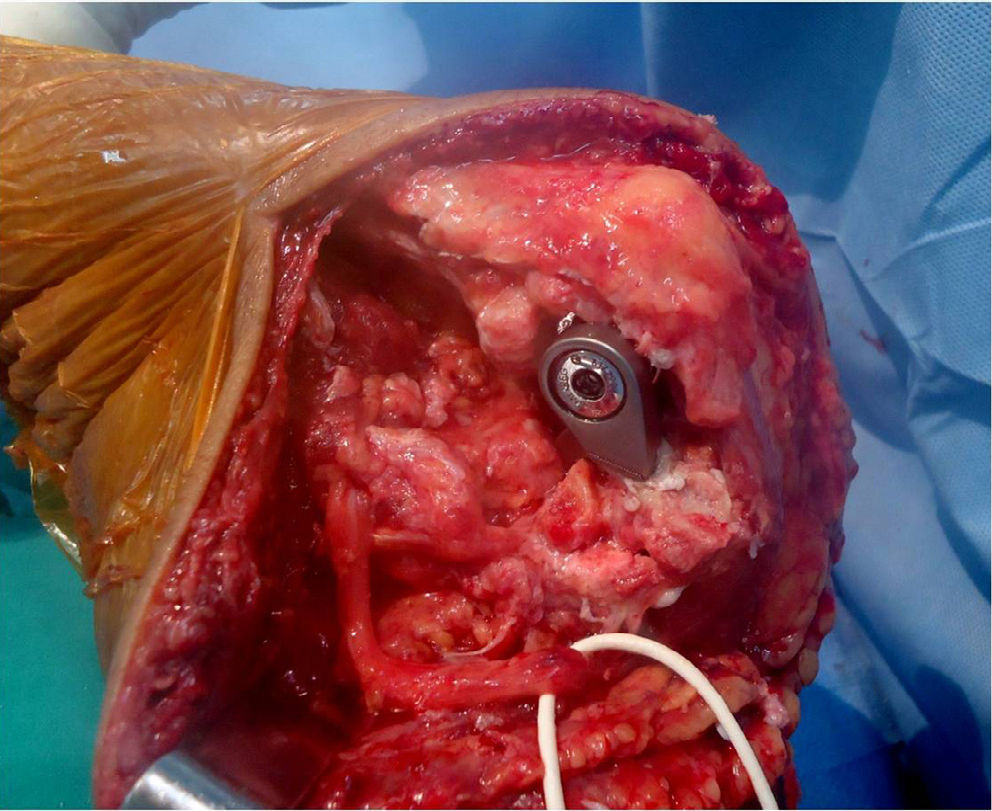

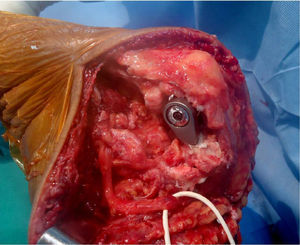

After washing the medullar canals the medullar cap is place in the humerus and the humeral and cubital components are cemented using a pistol. The components can be cemented separately and then joined by corresponding the pin and pivot pin, or they can be put into place already joined together. Once both components have been inserted the elbow is positioned at maximum extension until the cement has set (Fig. 2).

A fragment of the bone graft taken from the resected trochlea is use to carve a bone table which is placed between the anterior edge of the humeral component and the diaphysis, to increase the rotational stability of the implant.

The mobility achieved is tested and 3 aspects are evaluated: the extension obtained, which if limited requires the need for an anterior capsulectomy; if there is any block between the coronoid apophysis and the anterior fin of the prosthesis the coronoid is partially resected. If there is any friction between the prosthesis and the radial head then a radial head ostectomy is performed.

It is closed in planes and the epichondyle and epitrochlear muscles are sutured to the lateral and medial edges of the triceps. The cubital nerve is transposed anteriorly. A suction drain is put into place and the elbow is immobilised at 90° with a plaster valve during 72h.

Objective postoperative clinical evaluation is carried out by measuring movement with a goniometer and the strength of elbow extension on the scale from M0 to M5.

Subjective evaluation used the Mayo Clinic Score (MCS)18 and the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH)19 score, in a range of 0–100 points, in which 0 is the highest possible score and 100 is the lowest. Pain and satisfaction with the procedure were evaluated on the analogue visual scale (AVS) with a range from 0 to 10.

Radiological evaluation was performed using frontal and profile X-rays immediately after the operation, after one month, and at 3, 6 and 12 months each year until the end of the follow-up.

Loosening was evaluated on the scale of Morrey et al.,7 which classified it as: (a) grade 0: radiolucent line <1mm and enveloping <50% of the interface; (b) grade 1: 1mm radiolucent line enveloping <50% of the interface; (c) grade 2: radiolucent line >1mm enveloping >50% of the interface; (d) grade 3: radiolucent line >2mm enveloping the whole interface; (e) grade 4: gross loosening. The presence of heterotopic calcification was evaluated, and it was classified as minimum, moderate and severe.

Average follow-up was 40 months (range from 13 to 96 months).

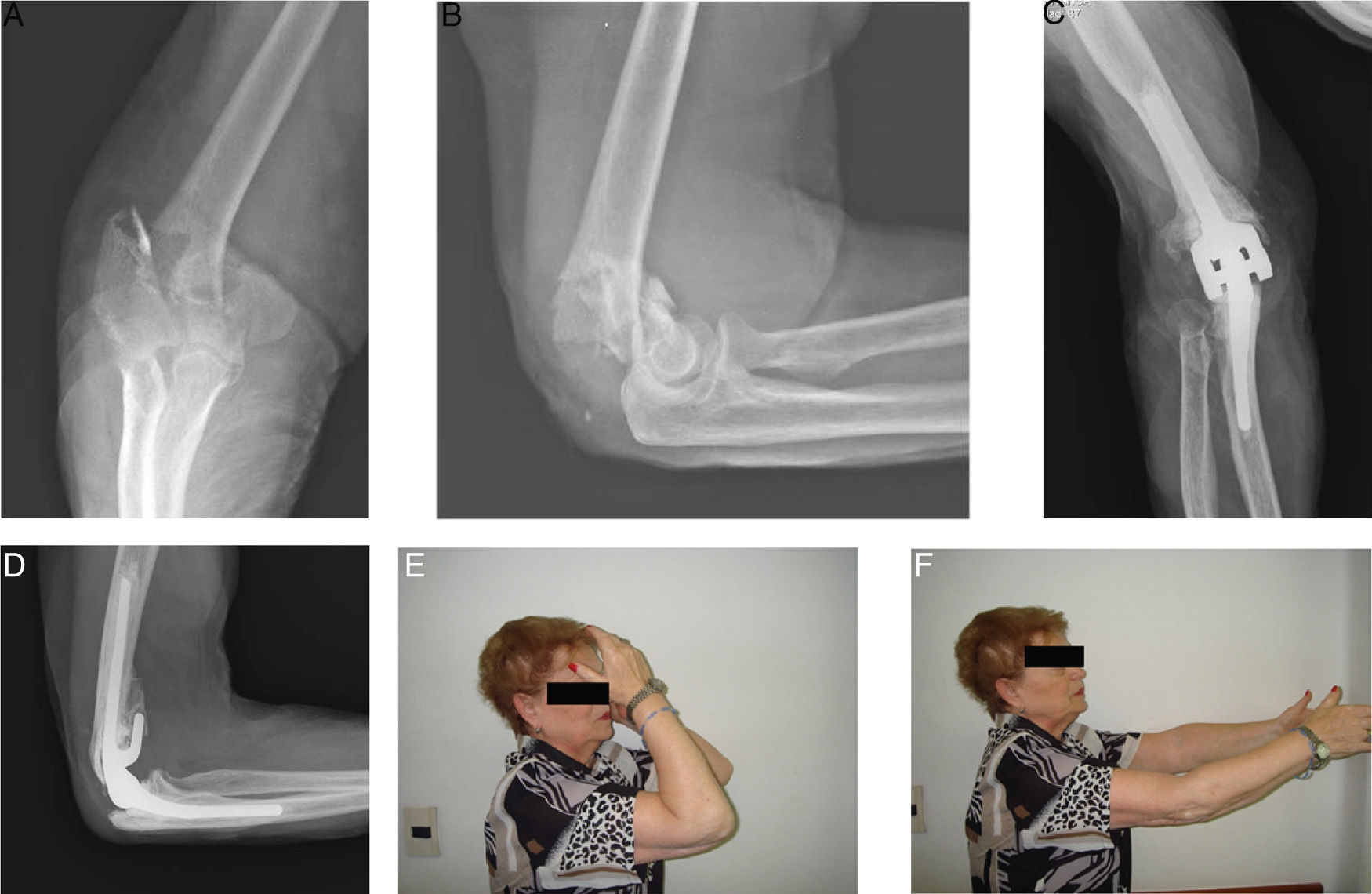

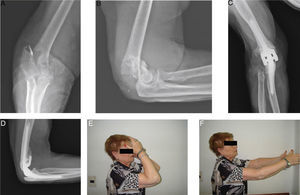

ResultsThe average flexion was 123° (range from 100° to 140°) and the average extension was 17° (range 0–45°), which corresponds to an average mobility arc of 106° (range 140–75°). The contralateral side had an average mobility arc of 133° (range 70–140°), so that 80% mobility was achieved in comparison with the healthy side.

Extension force was M4 in 4 patients and M5 in 19.

Average pain measured by the AVS was 1 point (range 0–5), and 11 patients reported 0 pain in this evaluation.

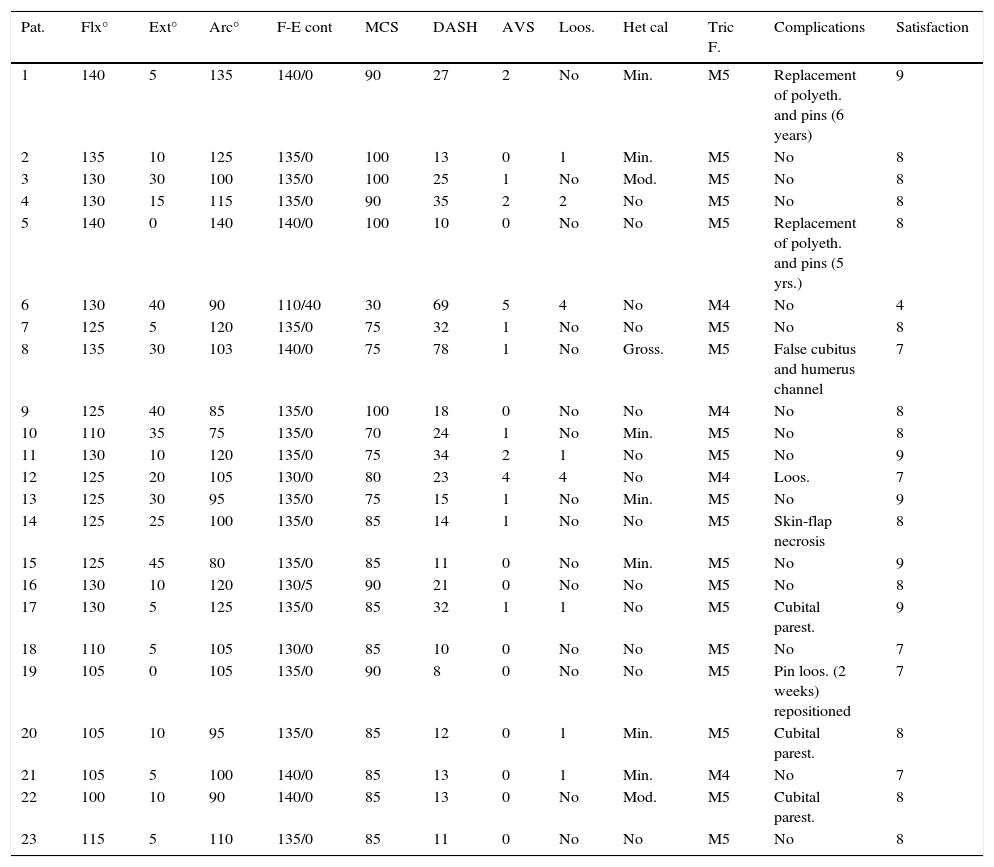

The average MCS was 83 points (range 30–100); 8 patients had excellent results, 13 good results, one mediocre and one poor. The average DASH score was 24 points (range 8–78) (Table 2).

Results.

| Pat. | Flx° | Ext° | Arc° | F-E cont | MCS | DASH | AVS | Loos. | Het cal | Tric F. | Complications | Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 140 | 5 | 135 | 140/0 | 90 | 27 | 2 | No | Min. | M5 | Replacement of polyeth. and pins (6 years) | 9 |

| 2 | 135 | 10 | 125 | 135/0 | 100 | 13 | 0 | 1 | Min. | M5 | No | 8 |

| 3 | 130 | 30 | 100 | 135/0 | 100 | 25 | 1 | No | Mod. | M5 | No | 8 |

| 4 | 130 | 15 | 115 | 135/0 | 90 | 35 | 2 | 2 | No | M5 | No | 8 |

| 5 | 140 | 0 | 140 | 140/0 | 100 | 10 | 0 | No | No | M5 | Replacement of polyeth. and pins (5 yrs.) | 8 |

| 6 | 130 | 40 | 90 | 110/40 | 30 | 69 | 5 | 4 | No | M4 | No | 4 |

| 7 | 125 | 5 | 120 | 135/0 | 75 | 32 | 1 | No | No | M5 | No | 8 |

| 8 | 135 | 30 | 103 | 140/0 | 75 | 78 | 1 | No | Gross. | M5 | False cubitus and humerus channel | 7 |

| 9 | 125 | 40 | 85 | 135/0 | 100 | 18 | 0 | No | No | M4 | No | 8 |

| 10 | 110 | 35 | 75 | 135/0 | 70 | 24 | 1 | No | Min. | M5 | No | 8 |

| 11 | 130 | 10 | 120 | 135/0 | 75 | 34 | 2 | 1 | No | M5 | No | 9 |

| 12 | 125 | 20 | 105 | 130/0 | 80 | 23 | 4 | 4 | No | M4 | Loos. | 7 |

| 13 | 125 | 30 | 95 | 135/0 | 75 | 15 | 1 | No | Min. | M5 | No | 9 |

| 14 | 125 | 25 | 100 | 135/0 | 85 | 14 | 1 | No | No | M5 | Skin-flap necrosis | 8 |

| 15 | 125 | 45 | 80 | 135/0 | 85 | 11 | 0 | No | Min. | M5 | No | 9 |

| 16 | 130 | 10 | 120 | 130/5 | 90 | 21 | 0 | No | No | M5 | No | 8 |

| 17 | 130 | 5 | 125 | 135/0 | 85 | 32 | 1 | 1 | No | M5 | Cubital parest. | 9 |

| 18 | 110 | 5 | 105 | 130/0 | 85 | 10 | 0 | No | No | M5 | No | 7 |

| 19 | 105 | 0 | 105 | 135/0 | 90 | 8 | 0 | No | No | M5 | Pin loos. (2 weeks) repositioned | 7 |

| 20 | 105 | 10 | 95 | 135/0 | 85 | 12 | 0 | 1 | Min. | M5 | Cubital parest. | 8 |

| 21 | 105 | 5 | 100 | 140/0 | 85 | 13 | 0 | 1 | Min. | M4 | No | 7 |

| 22 | 100 | 10 | 90 | 140/0 | 85 | 13 | 0 | No | Mod. | M5 | Cubital parest. | 8 |

| 23 | 115 | 5 | 110 | 135/0 | 85 | 11 | 0 | No | No | M5 | No | 8 |

Het cal, heterotopic calcifications; DASH, disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand; AVS, analogue visual scale; F-E cont, flexion extension; Tric F., triceps force; MCS, Mayo Clinic Score.

Prosthesis loosening was classified as grade 1 in 5 patients, grade 2 in one and grade 4 in 2. No loosening was found in 15 patients.

Gross heterotopic calcifications were detected in one patient, while in 2 calcifications were moderate, in 7 they were minimum and none were found in 13.

10 complications arose: 2 patients were operated again due to wear of the polyethylene (it was changed together with the pivot pins of the assembly) (Fig. 3); one patient was operated again 2 weeks after the surgery to reposition an assembly pivot pin due to a technical error in the positioning of the same; 3 patients had paresthesias in the territory of the cubital nerve; one patient had necrosis of the skin and cellular tissue due to a haematoma, and required a pediculated lateral flap of the arm to cover it; 2 patients presented loosening of the humeral component although they did not require another operation, and one patient had a false channel of the cubitus and humerus during the surgery which required wire cerclage at humeral level and postoperative immobilisation with a splint for one month.

The average satisfaction with the procedure was 8 (range 4–9).

No infections occurred.

DiscussionThe classic treatment for DHF is reduction and osteosynthesis. This is the treatment of choice for young patients, and good bone quality often aids fixing.20,21 This is not the case for older patients, whose fractures are generally complex and with a certain or major degree of comminution and osteoporosis. Osteosynthesis is usually harder and often requires long periods of immobilisation that increase the risk of complications and a poor outcome. It is in such cases that replacement with a prosthesis is able to play an important role in treatment.

The first indications for arthroplasty in connection with a traumatic episode were for the treatment of sequelae of fractures or pseudoarthrosis,22–24 and subsequently results using this in acute injuries were published.

In the year 2004 Kamineni and Morrey25 published the results in 43 patients operated for DHF after an average of 7 years. 93% of the patients obtained excellent or good results, with the recovery of a flexo-extension arc of 131–24°. X-rays showed radiolucent lines in 9 patients, and they reported complications in about 50% of the cases, including 11 infections, 3 fractures of the cubitus and 3 cases of loosening which required prosthesis revision. 5 other subsequent studies confirmed these preliminary findings.26–30

Frankle et al.12 were the first to report better results with arthroplasties than with internal fixing in patients >65 years old, with fewer complications (14% in the arthroplasty group and 26% in the internal fixing group).

In 2014 Mansat et al.31 reported the results of a multicentre study of 87 patients >65 years old, with DHF and treated using a Coonrad–Morrey arthroplasty. The vast majority were women, with an average age of 79 years old. At 37 months of follow-up, the MCS stood at 86 points and the Quick-DASH at 24, while 64% of the patients had no pain. 48% of the patients achieved a mobility arc of 100°, complications had arisen in 23% of the cases (20/87) and revision surgery had taken place in 9% (8 cases).

In general, reports on prosthetic replacements cite a functional arc of mobility with a restriction in the final degrees of extension. In our series of cases this was 17° (a little less than is reported by other authors). The patients in our series did not consider this extension deficit to be an important problem (Fig. 4A).

Conservation of the triceps allowed us to start rehabilitation early, and this may explain the recovery of a mobility arc of 106°; on the other hand, this was aided by the fact that there were no extensor apparatus complications. In these cases we do not believe osteotomy of the olecranon to raise the triceps to be necessary, as some authors describe,32 or the disinsertion of the same as occurs in the majority of cases published by Mansat et al.31

In our series it was important to keep good elbow extension strength, given that the majority of the patients are elderly and often need to use a walking stick to walk.

We had 2 cases of gross loosening of the humeral component. Both of these were associated with a defect in the cementation of the same. This number is comparable to those in other series. The decision not to repeat the operation was due to the advanced age of the patients and their refusal to subject themselves to another surgical procedure. However, a revision would surely have been necessary in younger patients.

Other important complications were permanent paresthesias of the cubital nerve. Careful intraoperative care is fundamental to avoid this, as full neurological non-recovery is frequent, above all in elderly patients.

According to several authors wear of the polyethylene is a rare complication (1.3% of 919 implants according to Lee et al.33). This drawback occurred in 2/23 of our patients. We believe that it may be associated with poor component alignment, chiefly the humeral one. Complete resection of the lower end of the humerus may create conditions that will lead to incorrect positioning of the implant, and this may lead to overloading between both components. In both case the prosthesis was found to be implanted and correctly cemented with consolidation of the anterior graft. These patients developed satisfactorily after replacement.

Hemiarthroplasty has been described recently, although series are limited and have short follow-up periods. This implant is indicated to ensure stability when the columns are preserved, or if it is possible to set them. Although complications have been described, this may be a valid option, especially in younger patients.34,35

Only 2 patients in our series were younger than 65 years old. Celli and Morrey36 presented 49 cases of arthroplasty in younger patients (30 due to inflammation and 19 following injury) with an average age of 33 years old. 93% of their results were good or excellent at 91 months of follow-up. However, the revision rate was 22%.

In spite of the high number of complications and repeat operations in our series, 19/23 patients presented good or excellent results in the final evaluation.

This work has certain limitations. It is a retrospective series with a small number of patients operated by different surgeons in different centre and evaluated by different professionals. Nevertheless, there are few other references to the procedure in question in the literature, and there were no losses during the follow-up of this consecutive series of patients.

The treatment of DHF using total elbow arthroplasty is a reasonable treatment option, although indications should be restricted to complex fractures in which the internal anchorage may be precarious, in patients with osteoporosis and low functional demand. In young patients this technique is indicated in serious cases in which there is no other treatment option.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gallucci GL, Larrondo Calderón W, Boretto JG, Castellaro Lantermo JA, Terán J, de Carli P. Artroplastia total de codo para el tratamiento de fracturas del húmero distal. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:167–174.