To determine the clinical and functional differences at hospital admission and at 1 year after a hip fracture (HF) in nursing homes (NH) and community-dwelling (CD) patients.

MethodsAll patients with HF admitted to the orthogeriatric unit at a university hospital between January 2013 and February 2014 were prospectively included. Clinical and functional variables, and mortality were recorded during the hospital admission. The patients were contacted by telephone at 1 year to determine their vital condition and functional status.

ResultsA total of 509 patients were included, 116 (22.8%) of whom came from NH. Compared with the CD patients, the NH patients had higher surgical risk (ASA ≥3: 83.6% vs. 66.4%, P<.001), poorer theoretical vital prognosis (Nottingham Profile ≥5: 98.3% vs. 56.6%, P<.001), higher rate of previous functional status (median Barthel index: 55 [IQR, 36-80] vs. 90 [IQR, 75-100], P<.001), poorer mental status (Pfeiffer's SPMSQ>2: 74.1% vs. 40.2%, P<.001), and a higher rate of sarcopenia (24.3% vs. 15.2%, P<.05). There were no differences in in-hospital or at 1-year mortality. At 1 year, NH patients recovered their previous walking capacity at a lower rate (38.5% vs. 56.2%, P<.001).

ConclusionsAmong the patients with HF treated in an orthogeriatric unit, NH patients had higher, surgical risk, functional and mental impairment, and a higher rate of sarcopenia than CD patients. At 1 year of follow-up, NH patients did not have higher mortality, but they recovered their previous capacity for walking less frequently.

Determinar las diferencias clínicas y funcionales, basales y al año de la fractura, en los pacientes hospitalizados por fractura de cadera (FC) que provienen de residencia de ancianos (RA) y de la comunidad.

MétodosSe incluyeron de forma prospectiva todos los pacientes ingresados con el diagnóstico de FC en la unidad de ortogeriatría de un hospital universitario entre enero de 2013 y febrero de 2014. Se recogieron variables clínicas, funcionales, cognitivas y la evolución durante la hospitalización. Se contactó telefónicamente al año para conocer su estado vital y funcional.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 509 pacientes, de los que 116 (22,8%) provenían de RA. Comparados con las personas que provenían de comunidad, éstos tenían un mayor riesgo quirúrgico (ASA≥3: 83,6% vs. 66,4%, p<0,001), peor pronóstico vital teórico (Perfil de Nottingham≥5: 98,3% vs. 56,6%, p<0,001), peor estado funcional basal (Índice Barthel medio: 55 [RIC, 36-80] vs. 90 [RIC, 75-100], p<0,001), peor estado mental (Test de Pfeiffer>2: 74,1% vs. 40,2%, p<0,001) y tasas más altas de sarcopenia (24,3% vs. 15,2%, p<0,05). No hubo diferencias en la mortalidad durante la hospitalización ni al año. Al año los pacientes de RA recuperaron su capacidad de ambulación previa con menos frecuencia (38,5% vs. 56,2%, p<0,001).

ConclusionesLos pacientes ingresados por FC provenientes de RA presentan mayor riesgo quirúrgico, mayor deterioro funcional y mental y mayor tasa de sarcopenia que los pacientes de la comunidad. No presentan mayor mortalidad durante el ingreso ni al año de la FC, pero recuperan su capacidad de deambulación previa con menos frecuencia.

Hip fractures (HF) are a prevalent condition and cause high mortality and functional disability.1 The number rate of HFs was estimated at 620,000 cases in 2010 in the European Union and at more than 210,000 cases per year in the USA between 2008 and 2011.2Between 17% and 40% of all patients with HF come from nursing homes (NH).1,3,4 Studies have suggested that NH patients are older, have poorer functional status, poorer ambulation capacity, higher cognitive impairment, a higher comorbidity rate, higher consumption of drugs and a poorer nutritional status than community-dwelling (CD) patients.5–12 After a HF, NH patients tend to have higher mortality and functional impairment rates than CD patients.8,10,12–14

Many studies that analyzed the characteristics and outcomes of patients with HF did not include individuals from NHs. Those studies that did include them often had small series 5,8,13,15or made no comparisons with those from the community.4,6,13 A number of studies have not included functional 3,9,15–18clinical or analytical variables 7,11,15,17or did not describe the treatment used during the hospitalization.6,11,17 Lastly, most of the series had a brief or nonexistent follow-up.3,5,7,9

It would be interesting to know whether these previously mentioned partial differences could be confirmed in a broad population-based study. Such a study should include all patients with HF (from NHs and CD), include a comprehensive geriatric assessment with several variables that could be involved in these patients (clinical, functional, nutritional, somatic and analytical endpoints) and perform a long-term follow-up.

The aim of this study was to report the baseline clinical and functional characteristics of patients with HF who came from NHs and compare them with those of CD patients in a representative population cohort. The secondary objectives were to determine whether there were differences in these patients’ clinical outcome during hospitalization and at 1 year after the hospitalization.

Materials and MethodsStudy designA descriptive observational cohort study.

Participants and settingThe study included all patients aged 65 years and older consecutively hospitalized in a public 1300-bed university hospital with a diagnosis of fragility HF between January 25, 2013 and February 26, 2014. This hospital has a catchment area of 520,000 inhabitants, with 4755 residents living in 41 nursing homes. Patients with HF are admitted from the emergency department to the Orthogeriatric Unit, whose activities have been described in previous papers.19–21 Patients hospitalized in this unit undergo a comprehensive geriatric assessment and a study of their fall on admission and are jointly treated during hospitalization by an orthogeriatrician, an orthopedic surgeon and an orthogeriatric nurse. Patients are helped out of bed on the first day after surgery and are asked to bear their own weight on the second day. The physiotherapist treats the patients in the same ward where they are hospitalized. The orthogeriatric team plans the discharge and assesses the need for referral to a geriatric rehabilitation unit after discharge. During the hospital stay, patients receive routine orthogeriatric care and undergo a standardized treatment protocol (known as FONDA for Function, Osteoporosis, Nutrition, Pain [dolor=spanish for pain] and Anemia).22 The aim of this protocol is to optimize physical function (active and passive exercises in bed and in a chair since the time of admission and standing after surgery), bone health (early normalization of vitamin D plasma levels), nutrition (oral nutritional supplements in cases of hypoproteinemia or body mass index <24kg/m2), pain (analgesia scheduled every 4h) and anemia (administration of intravenous iron if iron deficiency or risk of iron deficiency [ferritin<20mg/mL or ferritin<200mg/mL+transferrin saturation<20%] are detected and transfusion of packed red blood cells if hemoglobin levels are <9g/dL or <10g/dL in patients with disease of a vital organ).

Baseline and admission assessmentAll patients were assessed during the first 72?h after admission and always before surgery. A clinical interview was conducted to collect data on the following baseline variables: clinical (past medical history and medications), functional (previous Functional Ambulation Category [FAC] scale (0=Nonfunctional ambulator, 1=Ambulator, dependent on physical assistance – level I, 2=Ambulator, dependent on physical assistance – level II, 3=Ambulator, dependent on supervision, 4=Ambulator, independent level surface only, 5=Ambulator, independent)) 23and Barthel index [BI],24 cognitive (Red Cross Mental Scale [CRM] 25and Pfeiffer's Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire [SPMSQ],26 blood test (hemogram and biochemistry, total protein, albumin and vitamin?D) and previous medications.

We applied the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) anesthetic risk scale classification,27 the Charlson comorbidity index (abbreviated version) 28and the Nottingham Hip Fracture Score (NHFS).29,30 Within the NHFS variable, we used the Pfeiffer test instead of the Mini Mental Test Score, given that the former is the 10-item test most often applied in Spanish hospitals.31 Body mass index (BMI), muscle mass, grip strength and sarcopenia were also assessed at this time, as described in previous papers.32 The cut-off points of the Italian inCHIANTI (Invecchiare in Chianti, aging in the Chianti area) study were applied, which were 20?kg for women and 30?kg for men.33,34 A patient was considered to have sarcopenia if they met the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) criteria for low muscle mass and low muscle strength.33

Assessment at dischargeDuring the last 24h before discharge, the patient's pain when mobilizing the affected limb was assessed using a verbal descriptive scale from 0 to 5 (0 - no pain, 5 - maximum pain).35 We recorded the variables for medical treatment, surgery, rehabilitation and hospital length of stay. We also recorded the variables for function (FAC scale and BI), post-discharge destination and hospital mortality.

Assessment at 1 yearTelephone contact was made at 12 months after the fracture, during which we recorded the variables of the patient's vital status, functional status (FAC) and hospital readmissions. To determine the change in the patient's functional status the variable “change in FAC” was created following the formula “baseline FAC minus “at one year” FAC”.12 Change in functional status was designated as “no change” if the result was zero, “moderate change” if the difference was 1 point and “major change” if the difference was>1 point.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the La Paz University Hospital (Reference HULP-PI-1334). Informed consent was obtained from all the patients or relatives before the patients’ inclusion in the study.

Statistical analysisThe results for the quantitative variables are described using the mean and standard deviation (SD) for the variables with a normal distribution and with the median and interquartile range for those without a normal distribution. The qualitative variables are described using frequencies. We established 2 groups according to place of residence: NH and CD. The statistical association of each variable with place of residence was calculated using the chi-squared test for the qualitative variables and with Student's t-test for the quantitative variables with a normal distribution and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normal distribution. Normality was verified by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The statistical package used for the analysis was SPSS, version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

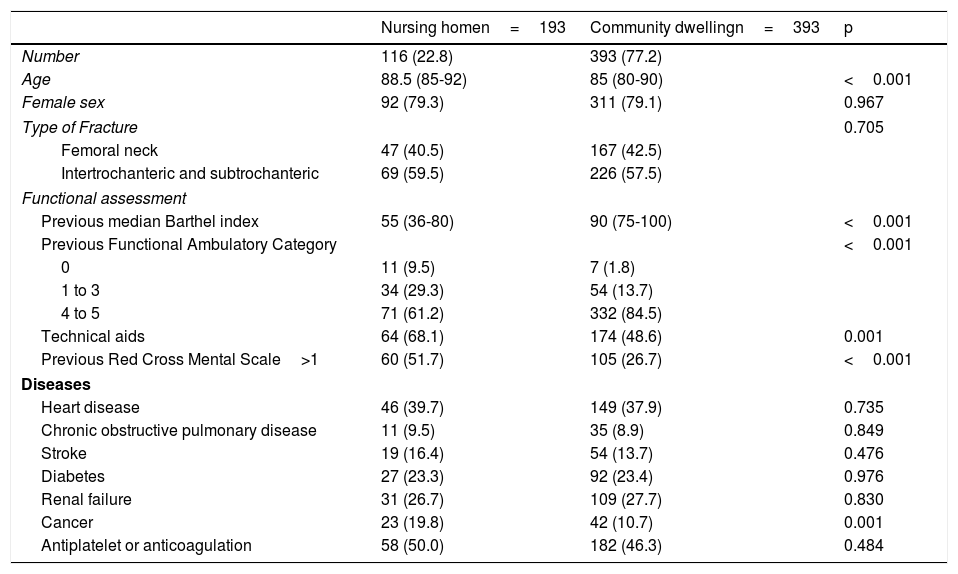

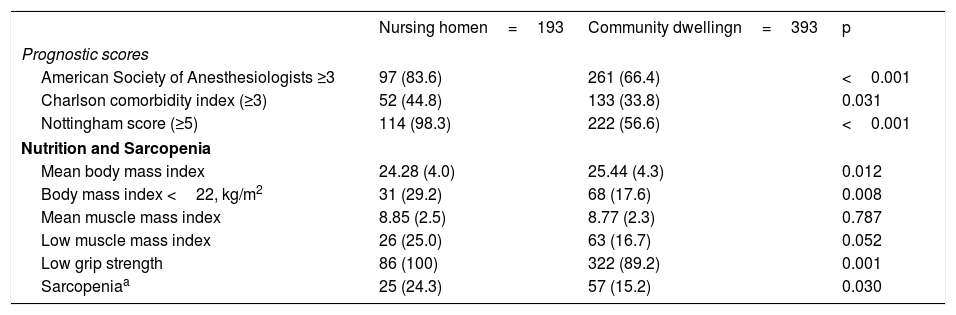

ResultsPatient CharacteristicsDuring the study period, 535 patients were admitted, 509 of whom (95%) were eligible for inclusion. One hundred and sixteen (22.8%) of the patients came from NHs. The NH patients were older and had poorer previous functional and cognitive status (Table 1). There were no differences in the disease rates, except for cancer, which was more common among the NH patients. The NH patients had greater comorbidity (Charlson index), higher surgical risk (ASA scale), poorer vital prognoses (Nottingham Score), poorer nutritional status and a higher rate of sarcopenia (Table 2).

Baseline Characteristics of the Hip Fracture Patients from Nursing Homes and Community Dwelling. Results expressed as median (interquartile range) or number (percentage).

| Nursing homen=193 | Community dwellingn=393 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 116 (22.8) | 393 (77.2) | |

| Age | 88.5 (85-92) | 85 (80-90) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 92 (79.3) | 311 (79.1) | 0.967 |

| Type of Fracture | 0.705 | ||

| Femoral neck | 47 (40.5) | 167 (42.5) | |

| Intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric | 69 (59.5) | 226 (57.5) | |

| Functional assessment | |||

| Previous median Barthel index | 55 (36-80) | 90 (75-100) | <0.001 |

| Previous Functional Ambulatory Category | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 11 (9.5) | 7 (1.8) | |

| 1 to 3 | 34 (29.3) | 54 (13.7) | |

| 4 to 5 | 71 (61.2) | 332 (84.5) | |

| Technical aids | 64 (68.1) | 174 (48.6) | 0.001 |

| Previous Red Cross Mental Scale>1 | 60 (51.7) | 105 (26.7) | <0.001 |

| Diseases | |||

| Heart disease | 46 (39.7) | 149 (37.9) | 0.735 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 11 (9.5) | 35 (8.9) | 0.849 |

| Stroke | 19 (16.4) | 54 (13.7) | 0.476 |

| Diabetes | 27 (23.3) | 92 (23.4) | 0.976 |

| Renal failure | 31 (26.7) | 109 (27.7) | 0.830 |

| Cancer | 23 (19.8) | 42 (10.7) | 0.001 |

| Antiplatelet or anticoagulation | 58 (50.0) | 182 (46.3) | 0.484 |

Differences in Prognostic Scores, Nutrition and Sarcopenia among Hip Fracture Patients from Nursing Homes and Community Dwelling. Results expressed as mean (± standard deviation) or number (percentage).

| Nursing homen=193 | Community dwellingn=393 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prognostic scores | |||

| American Society of Anesthesiologists ≥3 | 97 (83.6) | 261 (66.4) | <0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (≥3) | 52 (44.8) | 133 (33.8) | 0.031 |

| Nottingham score (≥5) | 114 (98.3) | 222 (56.6) | <0.001 |

| Nutrition and Sarcopenia | |||

| Mean body mass index | 24.28 (4.0) | 25.44 (4.3) | 0.012 |

| Body mass index <22, kg/m2 | 31 (29.2) | 68 (17.6) | 0.008 |

| Mean muscle mass index | 8.85 (2.5) | 8.77 (2.3) | 0.787 |

| Low muscle mass index | 26 (25.0) | 63 (16.7) | 0.052 |

| Low grip strength | 86 (100) | 322 (89.2) | 0.001 |

| Sarcopeniaa | 25 (24.3) | 57 (15.2) | 0.030 |

From the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People criteria for low muscle mass and low muscle strength33. The gait speed criterion could not be applied because these patients had not yet undergone surgery for the fracture.

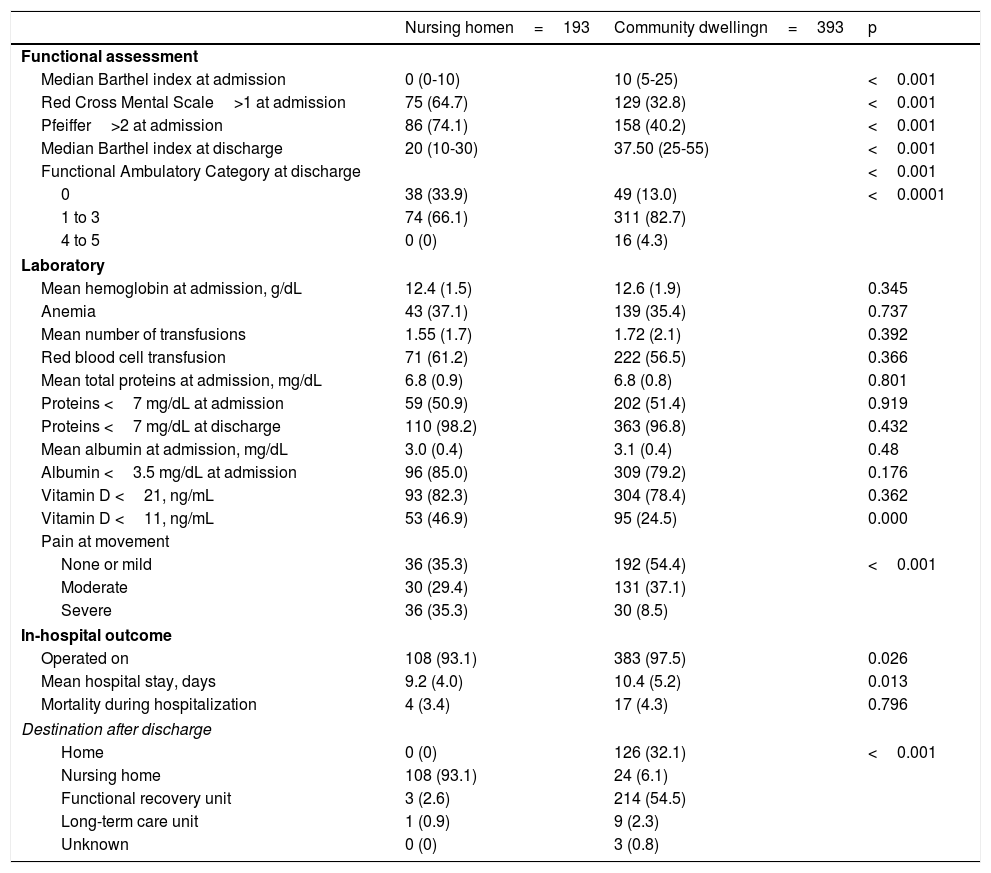

During hospitalization, the NH patients had a poorer functional, cognitive and nutritional status (Table 3). There were no differences in the blood test variables, except for a higher rate of severe vitamin D deficiency (<11 ng/mL) in the NH patients. Pain intensity at discharge was higher in the NH patients. There were no differences in hospital mortality between the 2 groups.

Characteristics during the Hospitalization of the Hip Fracture Patients from Nursing Homes and Community Dwelling. Results expressed as mean (± standard deviation), median (interquartile range) or number (percentage).

| Nursing homen=193 | Community dwellingn=393 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional assessment | |||

| Median Barthel index at admission | 0 (0-10) | 10 (5-25) | <0.001 |

| Red Cross Mental Scale>1 at admission | 75 (64.7) | 129 (32.8) | <0.001 |

| Pfeiffer>2 at admission | 86 (74.1) | 158 (40.2) | <0.001 |

| Median Barthel index at discharge | 20 (10-30) | 37.50 (25-55) | <0.001 |

| Functional Ambulatory Category at discharge | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 38 (33.9) | 49 (13.0) | <0.0001 |

| 1 to 3 | 74 (66.1) | 311 (82.7) | |

| 4 to 5 | 0 (0) | 16 (4.3) | |

| Laboratory | |||

| Mean hemoglobin at admission, g/dL | 12.4 (1.5) | 12.6 (1.9) | 0.345 |

| Anemia | 43 (37.1) | 139 (35.4) | 0.737 |

| Mean number of transfusions | 1.55 (1.7) | 1.72 (2.1) | 0.392 |

| Red blood cell transfusion | 71 (61.2) | 222 (56.5) | 0.366 |

| Mean total proteins at admission, mg/dL | 6.8 (0.9) | 6.8 (0.8) | 0.801 |

| Proteins <7 mg/dL at admission | 59 (50.9) | 202 (51.4) | 0.919 |

| Proteins <7 mg/dL at discharge | 110 (98.2) | 363 (96.8) | 0.432 |

| Mean albumin at admission, mg/dL | 3.0 (0.4) | 3.1 (0.4) | 0.48 |

| Albumin <3.5 mg/dL at admission | 96 (85.0) | 309 (79.2) | 0.176 |

| Vitamin D <21, ng/mL | 93 (82.3) | 304 (78.4) | 0.362 |

| Vitamin D <11, ng/mL | 53 (46.9) | 95 (24.5) | 0.000 |

| Pain at movement | |||

| None or mild | 36 (35.3) | 192 (54.4) | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 30 (29.4) | 131 (37.1) | |

| Severe | 36 (35.3) | 30 (8.5) | |

| In-hospital outcome | |||

| Operated on | 108 (93.1) | 383 (97.5) | 0.026 |

| Mean hospital stay, days | 9.2 (4.0) | 10.4 (5.2) | 0.013 |

| Mortality during hospitalization | 4 (3.4) | 17 (4.3) | 0.796 |

| Destination after discharge | |||

| Home | 0 (0) | 126 (32.1) | <0.001 |

| Nursing home | 108 (93.1) | 24 (6.1) | |

| Functional recovery unit | 3 (2.6) | 214 (54.5) | |

| Long-term care unit | 1 (0.9) | 9 (2.3) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 3 (0.8) | |

At discharge, almost all NH patients returned to their NHs, while more than half of the CD patients were transferred to functional recovery units.

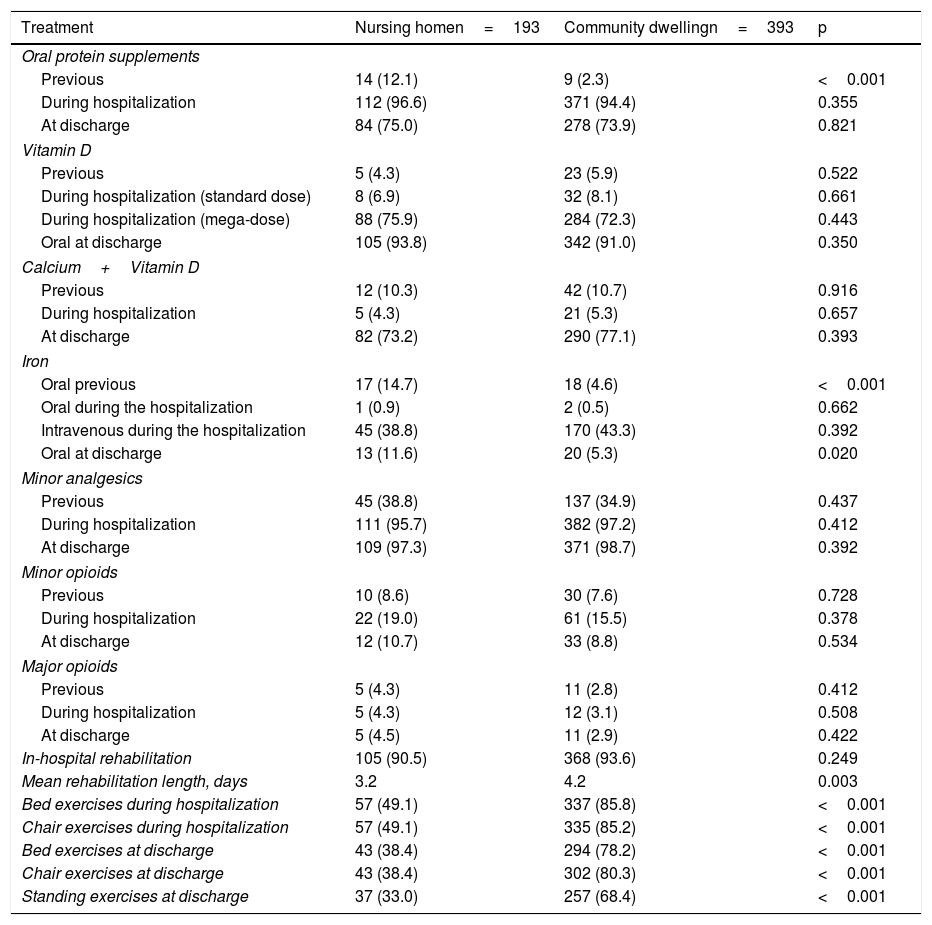

Treatments EmployedBoth patient groups underwent the same treatments in terms of the implementation of the standardized in-hospital management protocol and the same frequency of in-hospital rehabilitation treatment (Table 4). However, the NH patients underwent on average one fewer physical therapy session for walking and less frequently managed to perform bed and chair exercises from the time of admission, as well as standing exercises after surgery.

Treatments before and during the Hospitalization of the Hip Fracture Patients from Nursing Homes and Community Dwelling. Results expressed as numbers (percentage).

| Treatment | Nursing homen=193 | Community dwellingn=393 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral protein supplements | |||

| Previous | 14 (12.1) | 9 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| During hospitalization | 112 (96.6) | 371 (94.4) | 0.355 |

| At discharge | 84 (75.0) | 278 (73.9) | 0.821 |

| Vitamin D | |||

| Previous | 5 (4.3) | 23 (5.9) | 0.522 |

| During hospitalization (standard dose) | 8 (6.9) | 32 (8.1) | 0.661 |

| During hospitalization (mega-dose) | 88 (75.9) | 284 (72.3) | 0.443 |

| Oral at discharge | 105 (93.8) | 342 (91.0) | 0.350 |

| Calcium+Vitamin D | |||

| Previous | 12 (10.3) | 42 (10.7) | 0.916 |

| During hospitalization | 5 (4.3) | 21 (5.3) | 0.657 |

| At discharge | 82 (73.2) | 290 (77.1) | 0.393 |

| Iron | |||

| Oral previous | 17 (14.7) | 18 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| Oral during the hospitalization | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.5) | 0.662 |

| Intravenous during the hospitalization | 45 (38.8) | 170 (43.3) | 0.392 |

| Oral at discharge | 13 (11.6) | 20 (5.3) | 0.020 |

| Minor analgesics | |||

| Previous | 45 (38.8) | 137 (34.9) | 0.437 |

| During hospitalization | 111 (95.7) | 382 (97.2) | 0.412 |

| At discharge | 109 (97.3) | 371 (98.7) | 0.392 |

| Minor opioids | |||

| Previous | 10 (8.6) | 30 (7.6) | 0.728 |

| During hospitalization | 22 (19.0) | 61 (15.5) | 0.378 |

| At discharge | 12 (10.7) | 33 (8.8) | 0.534 |

| Major opioids | |||

| Previous | 5 (4.3) | 11 (2.8) | 0.412 |

| During hospitalization | 5 (4.3) | 12 (3.1) | 0.508 |

| At discharge | 5 (4.5) | 11 (2.9) | 0.422 |

| In-hospital rehabilitation | 105 (90.5) | 368 (93.6) | 0.249 |

| Mean rehabilitation length, days | 3.2 | 4.2 | 0.003 |

| Bed exercises during hospitalization | 57 (49.1) | 337 (85.8) | <0.001 |

| Chair exercises during hospitalization | 57 (49.1) | 335 (85.2) | <0.001 |

| Bed exercises at discharge | 43 (38.4) | 294 (78.2) | <0.001 |

| Chair exercises at discharge | 43 (38.4) | 302 (80.3) | <0.001 |

| Standing exercises at discharge | 37 (33.0) | 257 (68.4) | <0.001 |

During the 12-month follow-up, 10 CD patients moved outside the area and could not be located. Of the remaining patients in the NH and CD groups, 32 (27.6%) and 86 (21.9%) died, respectively (p=0.201). During the first year, 24 (27.6%) and 71 (23.6%) of the NH and CD patients were readmitted, respectively (p=0.479).

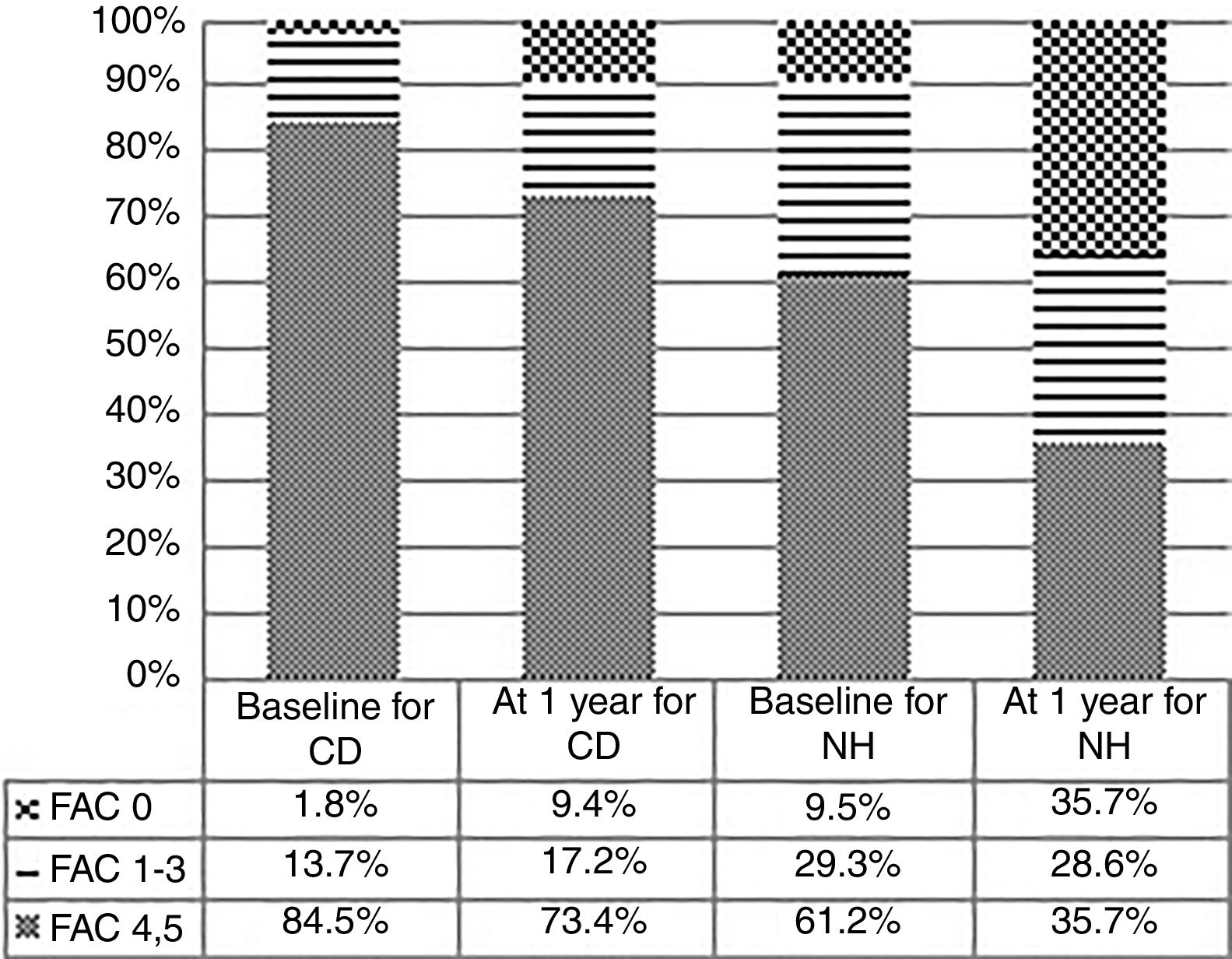

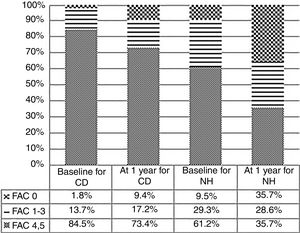

Functional OutcomeThe differences in previous ambulation level and at 12 months of the HF for the two groups are shown in Figure 1. The differences according to place of residence were statistically significant (p<0.001).

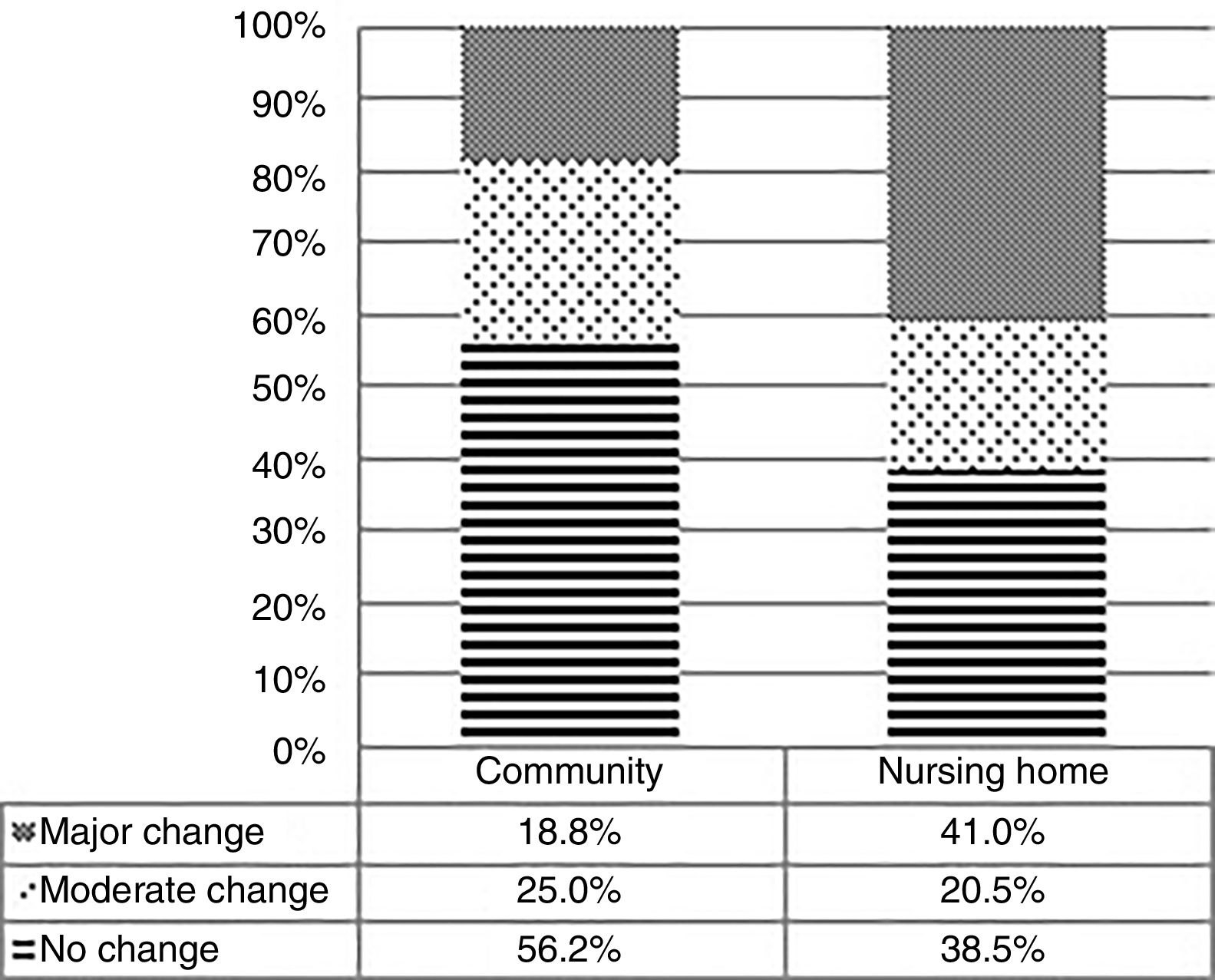

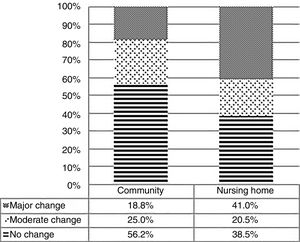

Lastly, Figure 2 shows the recovery rate and, if applicable, the magnitude of the change in the ambulation capacity at 1 year according to the FAC scale for the two patient groups. Some 38.5% of the NH patients and 56% of the CD patients recovered their previous level of ambulation (p<0.001).

Change in Functional Ambulation Category (FAC) from baseline to 1 year after a hip fracture in nursing homes and community dwelling patients. No change, moderate change (baseline FAC minus FAC at 1 year equal to 1) or major change (baseline FAC minus FAC at 1 year greater than 1) (p<0.001).

In this study, we compared the differences at baseline and during hospitalization and the results at 1 year for NH patients and CD patients with HFs. The NH patients had a poorer clinical, functional, cognitive and nutritional status, a higher rate of sarcopenia and higher pain intensity. The NH patients did not have higher hospital mortality or at 1 year of follow-up, but its functional decline in terms of ambulatory capacity was greater.

Patient CharacteristicsThe higher rate and intensity of functional and walking impairment 5,6,8,10,12,13as well as the higher rate of cognitive impairment 5,6,8,13and higher comorbidity 5,7–9,13in NH patients who experience a HF have been mentioned in previous studies. Our study also revealed that these patients have higher severity degree of systemic disease, as assessed through higher surgical risk on the ASA scale and a poorer theoretical vital prognosis as measured with the NHFS. The latter scale has been shown to predict mortality at 30 days 29,36and at 12 months 30after a HF This result shows that NH patients have higher clinical complexity when experiencing the HF process.

Malnutrition and low muscle mass and strength are known to be more common among the institutionalized population than among CD patients.8,11 The evaluation of sarcopenia in HF patients has a number of difficulties due to the problems of mobility and the method for assessing muscle mass. This, coupled with the fact that the NH population is rarely described in the literature, makes it difficult to find studies similar to ours.19,37

The rate of moderate to severe pain at discharge was higher in the NH patients despite being treated similarly to the CD patients. We do not know the cause for this finding, but it might be related to the observation by Killington et al. that, after hospitalization for HF, patients return to their NH complaining of poorly controlled pain,38 or it could be related to the finding by Feldt et al. that, after a HF, the pain is more intense in patients with cognitive impairment and in more elderly patients.39

Treatments EmployedAll cases were monitored daily by the geriatrician, the orthopedic surgeon and the orthogeriatric nurse. The treatments applied to the two study groups were similar, including surgery, unlike other series that found lower rates of surgery in NH patients.5,8,11,40

MortalityThere were no differences in hospital or at 1-year mortality between the two study groups, despite the presence of increased severity markers in the NH patients. A number of authors have found that living in a NH can be a risk factor for increased mortality during the hospital phase 11and at 1 year.13–15,17 Although we cannot demonstrate it due to the lack of a control group, we believe that having applied a specific clinical management protocol (intensive and identical for the two groups) contributed to the lack of differences in mortality between both groups. The fact that the mortality in relation to the mean age of the sample observed in this series was lower than that observed in other studies 14,40and that co-managed orthogeriatric care offers better survival results during the hospital phase 21leads us to the conclusion that the treatment employed in this study had a beneficial effect in this regard.

Functional OutcomeThe degree of impairment in the ambulation capacity was greater in the NH patients, as has been reported by other authors.10,12 This finding could be due to the patients having a poorer condition at admission or having undergone less rehabilitation treatment. During hospitalization, there were no differences in the percentage of patients who underwent in-hospital physical therapy; however, the NH patients underwent one fewer session and were less often able to perform the bed, chair and standing exercises that were indicated for them, perhaps due to their greater functional or cognitive impairment. Additionally, many of the CD patients (55%) were referred to rehabilitation units, unlike the NH patients who generally had this treatment at their own centers. The hospital where the study was conducted refers patients to two rehabilitation units headed by geriatricians, while NH patients are dispersed to 41 centers where the treatments could be highly variable. This situation, which has been mentioned by Ireland et al 40might need to be reconsidered to ensure the same quality of rehabilitation care regardless of the patients’ place of residence.

Our study's strengths are the large number of patients included and the fact that they are a representative sample of the population, given that our hospital is the only reference hospital in the area for this condition. The HFs treated at the hospital probably included all cases that occurred in the area over the year. Another strength was that no exclusion criteria were applied, except for patient refusal to be included. The orthogeriatric unit where the patients were admitted had, at the time of the study, 7 years of experience and had treated more than 3000 patients, using a specialized surgical and geriatric treatment protocol adapted to current scientific evidence. The number and type of variables included in the study is superior, as far as we know, to those of studies published to date. Lastly, we can also consider the 1-year follow-up of the patients after the HF as a strength.

The study limitations include not having a control group to show the efficacy of the applied protocol in a trial and, as has been mentioned, that once the acute phase had passed the patients did not get the same access to rehabilitation.

In conclusion, this study shows that the clinical differences between NH patients and CD patients are not as relevant to the patients’ vital status if the two groups undergo an intensive treatment in a specialized orthogeriatric unit. However, the functional status of NH patients, which is already poorer than that of CD patients at baseline, worsens disproportionately in the long term. Rehabilitation measures might therefore need to be intensified for these patients. Further research is needed to understand this vulnerable population in order to make better strategies to minimize their functional decline after a hip fracture.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This work was supported in part by a Grant to Emerging Research Groups 2012 from the Research Institute of La Paz University Hospital (IdiPAZ); by a grant from the Ayudas de Investigación en Salud, 2008-2011 Plan Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo, Instituto de Salud Carlos III – Subdirección General de Redes y Centros de Investigación Cooperativa as the funding entity, the Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa en Envejecimiento y Fragilidad (RETICEF RD12/0043/0019) co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER); and by a grant from Nestlé Health Science to the Fundación de Investigación of La Paz University Hospital. The sponsors were not involved in any aspect of the study or in preparing the manuscript.