In order to address the complexity of needs of dependent older people, multidimensional and person-centered needs assessment is required. The objective of this review is to describe met and unmet needs of dependent older people, living in the community or in institutions, and the factors associated with those needs. Selection criteria included papers about need asessment which employed the Camberwell Assesment of Need for the Elderly (CANE). A search through MEDLINE, SCOPUS, WOS and CINHAL databases was carried out. Twenty-one articles were finally included. Unmet needs were found more frequently in psychosocial areas (mainly in “company”, “daytime activities” and “psychological distress”) and in institutionalized population. In addition, unmet needs were often associated with depressive symptoms, dependency, and caregiver burden. Discrepancies between self-reported needs and needs perceived by formal and informal caregivers were identified. It is important that professionals and caregivers try to make visible the perspective of older people and their psychological and social needs, particularly when the person is dependent, depressed or cognitively impaired.

Se requieren evaluaciones multidimensionales y centradas en la persona que aborden adecuadamente las necesidades de la población mayor que precisa de cuidados. El objetivo de esta revisión es describir las necesidades cubiertas y no cubiertas, y los factores asociados con las mismas, en personas mayores dependientes que viven en la comunidad o en instituciones, de acuerdo con el Cuestionario Camberwell de Necesidades para Personas Mayores. Se emplearon las bases de datos Medline, Scopus, Web of Science y CINAHL. Finalmente se incluyeron 21 artículos. Los resultados indican que las necesidades no cubiertas se encuentran mayormente en áreas psicosociales («compañía», «actividades diarias» y «malestar psicológico») y en población institucionalizada. Las necesidades no cubiertas suelen asociarse con síntomas depresivos y dependencia en la persona mayor y sobrecarga del cuidador. Se identificaron discrepancias entre las necesidades percibidas por la persona mayor y las señaladas por cuidadores formales e informales. Finalmente, es importante que los profesionales y cuidadores se esfuercen en visibilizar la perspectiva de la persona mayor y sus necesidades psicológicas y sociales, especialmente si presenta dependencia, depresión o deterioro cognitivo.

Worldwide, the development of long-term care systems which ensure a good quality of life for dependent older people, by considering their individual preferences, is a challenge.1 In order to achieve this, a comprehensive approach to assess older people care needs is essential.2 Both, formal and informal care systems, must be able to address dynamically those needs, through multidimensional, valid and reliable person-centered evaluation instruments.3–5 Whilst most needs assessment tools focus on specific needs, such as physical, social or psychological,6 the Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE) constitutes a comprehensive geriatric assessment which includes a wide range of needs. A previous literature review looked at instruments for assessing the needs of populations with chronic diseases. Out of sixty-three instruments found, only one evaluated a wide range of needs in an integrated way: the Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN). This tool focused on middle age adults and is the predecessor of the CANE.6

The CANE assesses the extent to which formal and informal care systems manage to meet the needs of older people.3 Needs are divided into four dimensions, covering a total of 24 areas: the Physical Dimension, includes areas of Physical Health, Medication, Eyesight/Hearing/Communication, Mobility/Falls, Self-care and Continence; the Environmental Dimension, containing Accommodation, Looking after home, Food, Caring for someone else, Money, and Benefits; the Social Dimension, focused on Company, Intimate relationships, Daytime Activities, Information, and Abuse/Neglect; and lastly, the Psychological Dimension, including areas of Psychological Distress, Memory, Inadvertent self-harm, Deliberate self-harm, Substance abuse/dependency, Behavior, and Psychotic symptoms and delirium. For each area, the evaluator can identify if a need is present or not and whether a need is met or unmet. A “met need” is defined as a situation in which a person, who has difficulties in an area, is receiving appropriate help.7 On the other hand, an “unmet need” exists when either the adequate level of evaluation or care is not being received.7 This approach makes possible the identification of assistance gaps and relevant areas for interventions to take place, and especially, it shows priorities of the person from their own perspective. In addition, the final average of met and unmet needs indicates in which grade the needs are being covered for a group of people, allowing comparisons with other groups. Furthermore, this questionnaire considers three perspectives of needs which can be compared: older people's, their caregiver's, and the reference health professional's views on needs. Evidence shows that these perceptions may differ8 since professionals and caregivers may be ignoring some needs of the older person.7–10 Finally, the presence of unmet needs is an element that must be addressed, as it has been associated with both, a decrease in quality of life, and an increase in disruptive behavior and depressive symptoms in the older population.11–13

Over the last two decades, different lines of research have been developed with the CANE questionnaire, assessing the needs of older people in a variety of countries, with different levels of morbidity, functionality, and of those who use several types of services (long-stay institutions, day center, primary care, memory clinics, among others). However, a review on the patterns of needs found within these diverse contexts has not yet been carried out. In a recent meta-analysis8 about the needs of older people with dementia living in the community, it was found that their most prevalent total needs were mainly in the areas of memory, food, looking after home and money. That is, most of the support required by people with dementia was located in the environmental dimension. However, nothing was mentioned about which areas of needs were met or unmet. In fact, the authors concluded about the relevance of examining the variation of met and unmet needs separately.

Therefore, the main objective of this review was to describe met and unmet needs of dependent older people living in the community or in institutions, evaluated through the CANE instrument, and which factors are associated with those needs.

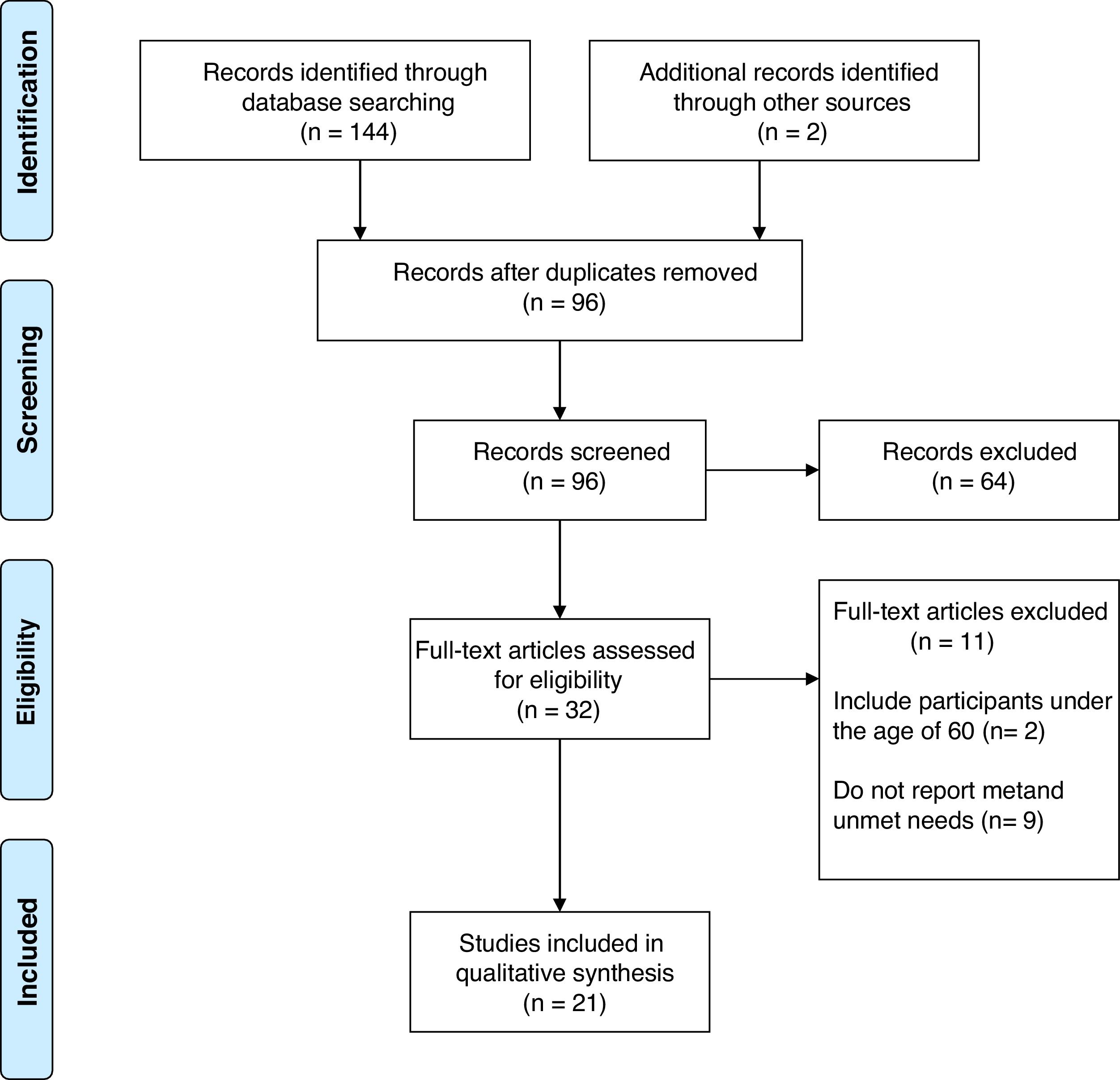

MethodsResearch strategiesThe selection of studies followed the guidelines of the flow chart by Moher and colleagues.14 A search of studies published in the last 20 years, in English or Spanish, was carried out through the MEDLINE, SCOPUS, Web of Science [WOS] and CINHAL databases using the keywords: “needs assessment”, “geriatric assessment”, “comprehensive evaluation”, “CANE”, and “older people”.

Exclusion and inclusion criteriaInclusion criteria comprised empirical, cross-sectional or longitudinal studies, that measured needs (through the CANE instrument) as a primary or secondary outcome in people aged 60 years or older. We excluded studies that did not fulfill these criteria, or those which used samples with broader age ranges and which did not perform subgroup analyses for the older population.

Data extractionThe study selection was carried out in three stages. First, records where identified through both, database searching and screening of selected papers’ references. Duplicates were removed, obtaining 96 references of which title and abstract were screened. Secondly, full texts of 32 studies were analyzed. Finally, studies that did not meet inclusion criteria or those which did not report all the required information were excluded, obtaining a total of 21 studies (see Fig. 1).

ResultsAlmost all the included studies had a cross-sectional design, except one.15 All of them used non-probabilistic samples, were written in English language and most came from Europe, with some exceptions.16,17 Regarding sample sizes, most of the studies comprised a small sample (within a range of 44–407 participants)18,19; except for Hoogendijk20 and Stein21 (with a sample of 1137 and 1179 people respectively). In addition, most participants were women with an average age ranging from 69 to 87 years.22,23 As can be seen in Table 1, a large part of the studies (n=13) focused on older people living in the community (recruited through general practitioners’ centers, primary care, day centers, social systems, among others). Eight studies included institutionalized older people, mainly in residential care (n=6), mental health centers (n=1), or hospitalized (n=1) (see Table 2). Most institutionalized people had an average age over 80 years.15,23–27

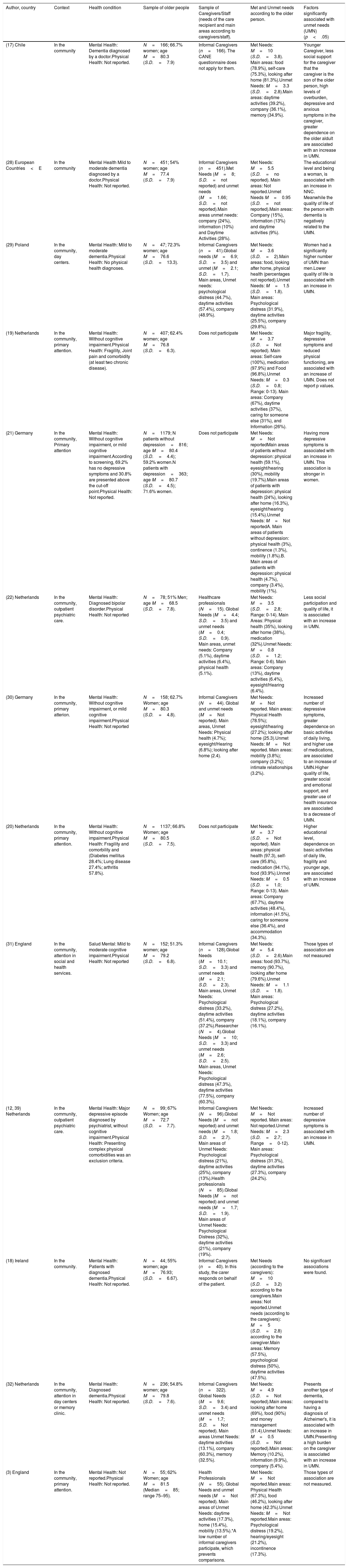

Results of selected studies with samples of community dwelling older adults.

| Author, country | Context | Health condition | Sample of older people | Sample of Caregivers/Staff (needs of the care recipient and main areas according to caregivers/staff). | Met and Unmet needs according to the older person. | Factors significantly associated with unmet needs (UMN) (p<.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (17) Chile | In the community | Mental Health: Dementia diagnosed by a doctor.Physical Health: Not reported. | N=166; 66.7% women; age M=80.3 (S.D.=7.9) | Informal Caregivers (n=166). The CANE questionnaire does not apply for them. | Met Needs: M=10 (S.D.=3.8). Main areas: food (78.9%), self-care (75.3%), looking after home (81.3%).Unmet Needs: M=3.3 (S.D.=2.8).Main areas: daytime activities (39.2%), company (36.1%), memory (34.9%). | Younger Caregiver, less social support for the caregiver that the caregiver is the son of the older person, high levels of overburden, depressive and anxious symptoms in the caregiver, greater dependence on the older aldult are associated with an increase in UMN. |

| (28) European Countries<E | In the community | Mental Health Mild to moderate dementia diagnosed by a doctor.Physical Health: Not reported. | N=451; 54% women; age M=77.4 (S.D.=7.9) | Informal Caregivers (n=451).Met Needs (M=8; S.D.=not reported) and unmet needs (M=1.66; S.D.=not reported).Main areas unmet needs: company (24%), information (10%) and Daytime Activities (28%). | Met Needs: M=5.5 (S.D.=no reported). Main areas: Not reported.Unmet Needs M=0.95 (S.D.=not reported).Main areas: Company (15%), information (13%) and daytime activities (9%). | The educational level and being a woman, is associated with an increase in NNC. Meanwhile the quality of life of the person with dementia is negatively related to the UMN. |

| (29) Poland | In the community, day centers. | Mental Health: Mild to moderate dementia.Physical Health: No physical health diagnoses. | N=47; 72.3% women; age M=76.6 (S.D.=13.3). | Informal Caregivers (n=41).Global needs (M=6.9; S.D.=3.5) and unmet (M=2.1; S.D.=1.7). Main areas, Unmet needs: psychological distress (44.7%), daytime activities (57.4%), company (48.9%). | Met Needs: M=3.6 (S.D.=2).Main areas: food, looking after home, physical health (percentages not reported).Unmet Needs: M=1.5 (S.D.=1.8). Main areas: Psychological distress (31.9%), daytime activities (25.5%), company (29.8%). | Women had a significantly higher number of UMN than men.Lower quality of life is associated with an increase in UMN. |

| (19) Netherlands | In the community, primary attention. | Mental Health: Without cognitive impairment.Physical Health: Fragility, Joint pain and comorbidity (at least two chronic disease). | N=407; 62.4% women; age M=76.8 (S.D.=6.3). | Does not participate | Met Needs: M=3.7 (S.D.=Not reported). Main areas: Self-care (100%), medication (97.9%) and Food (96.8%).Unmet Needs: M=0.3 (S.D.=0.8; Range: 0-13). Main areas: Company (67%), daytime activities (37%), caring for someone else (31%), and Information (26%). | Major fragility, depressive symptoms and reduced physical functioning, are associated with an increase of UMN. Does not report p values. |

| (21) Germany | In the community, Primary attention | Mental Health: Without cognitive impairment, or mild cognitive impairment.According to screening, 69.2% has no depressive symptoms and 30.8% are presented above the cut-off point.Physical Health: Not reported. | N=1179; N patients without depression=816; age M=80.4 (S.D.=4.4); 59.2% women.N patients with depression=363; age M=80.7 (S.D.=4.5); 71.6% women. | Does not participate | Met Needs: M=Not reportedMain areas of patients without depression: physical health (59.1%), eyesight/hearing (30%), mobility (19.7%).Main areas of patients with depression: physical health (24%), looking after home (16.3%), eyesight/hearing (15.4%).Unmet Needs: M=Not reportedA. Main areas of patients without depression: physical health (3%), continence (1.3%), mobility (1.8%).B. Main areas of patients with depression: physical health (4.7%), company (3.4%), mobility (1%). | Having more depressive symptoms is associated with an increase in UMN. This association is stronger in women. |

| (22) Netherlands | In the community, outpatient psychiatric care. | Mental Health: Diagnosed bipolar disorder.Physical Health: Not reported | N=78; 51% Men; age M=68.5 (S.D.=7.8). | Healthcare professionals (N=15). Global Needs (M=4.4; S.D.=3.5) and unmet needs (M=0.4; S.D.=0.9). Main areas, unmet needs: Company (5.1%), daytime activities (6.4%), physical health (5.1%). | Met Needs: M=3.5 (S.D.=2.8; Range: 0-14). Main Areas: Physical health (35%), looking after home (38%), medication (32%).Unmet Needs: M=0.8 (S.D.=1.2; Range: 0-6). Main areas: Company (13%), daytime activities (6.4%), eyesight/Hearing (6.4%). | Less social participation and quality of life, it is associated with an increase in UMN. |

| (30) Germany | In the community, primary atterion. | Mental Health: Without cognitive impairment, or mild cognitive impairment.Physical Health: Not reported | N=158; 62.7% Women; age M=80.3 (S.D.=4.8). | Informal Caregivers (N=44). Global and unmet needs (M=Not reported). Main areas, Unmet Needs: Physical health (4.7%); eyesight/Hearing (6.8%); looking after home (2.4). | Met Needs: M=Not reported. Main areas: Physical Health (78.5%); eyesight/hearing (27.2%); looking after home (25.3).Unmet Needs: M=Not reported. Main areas: mobility (3.8%); company (3.2%); intimate relationships (3.2%). | Increased number of depressive symptoms, greater dependence on basic activities of daily living, and higher use of medications, are associated to an increase of UMN.Higher quality of life, greater social and emotional support, and greater use of health insurance are associated to a decrease of UMN. |

| (20) Netherlands | In the community, primary attention. | Mental Health: Without cognitive impairment.Physical Health: Fragility and comorbility and (Diabetes mellitus 28.4%; Lung disease 27.4%; arthritis 57.8%). | N=1137; 66.8% Women; age M=80.5 (S.D.=7.5). | Does not participate | Met Needs: M=3.7 (S.D.=Not reported). Main areas: physical health (97.3), self-care (95.8%), medication (94.1%), food (93.9%).Unmet Needs: M=0.5 (S.D.=1.0; Range: 0-13). Main areas: Company (67.7%), daytime activities (48.4%), information (41.5%), caring for someone else (36.4%), and accommodation (34.3%). | Higher educational level, dependence on basic activities of daily life, fragility and younger age, are associated with an increase of UMN. |

| (31) England | In the community, attention in social and health services. | Salud Mental: Mild to moderate cognitive impairment.Physical Health: Not reported | N=152; 51.3% women; age M=79.2 (S.D.=6.8). | Informal Caregivers (n=128).Global Needs (M=10.1; S.D.=3.3) and unmet needs (M=2.1; S.D.=2.3). Main areas, Unmet Needs: Psychological distress (33.2%), daytime activities (51.4%), company (37.2%).Researcher (N=4).Global Needs (M=10; S.D.=3.3) and unmet needs (M=2.6; S.D.=2.5). Main areas, Unmet Needs: Psychological distress (47.3%), daytime activities (77.5%), company (60.3%). | Met Needs: M=5.4 (S.D.=2.6).Main areas: food (93.7%), memory (90.7%), looking after home (79.6%).Unmet Needs: M=1.1 (S.D.=1.8). Main areas: Psychological distress (27.2%), daytime activities (18.1%), company (16.1%). | Those types of association are not measured |

| (12, 39) Netherlands | In the community, outpatient psychiatric care. | Mental Health: Major depressive episode diagnosed by psychiatrist, without cognitive impairment.Physical Health: Presenting complex physical comorbidities was an exclusion criteria. | N=99; 67% Women; age M=72.7 (S.D.=7.7). | Informal Caregivers (N=96).Global Needs (M=not reported) and unmet needs (M=1.8; S.D.=:2.7). Main areas of Unmet Needs: Psychological distress (21%), daytime activities (25%), company (13%).Health professionals (N=85).Global Needs (M=not reported) and unmet needs (M=1.7; S.D.=1.9). Main areas of Unmet Needs: Psychological Distress (32%), daytime activities (21%), company (19%). | Met Needs: M=Not reported. Main areas: Not reported.Unmet Needs: M=2.3 (S.D.=2.7; Range=0-12). Main areas: Psychological distress (31.3%), daytime activities (27.3%), company (24.2%). | Increased number of depressive symptoms is associated with an increase in UMN. |

| (18) Ireland | In the community. | Mental Health: Patients with diagnosed dementia.Physical Health: Not reported. | N=44; 55% women; age M=76.93; (S.D.=6.67). | Informal Caregivers (n=40). In this study, the carer responds on behalf of the patient. | Met Needs (according to the caregivers): M=10 (S.D.=3.2) according to the caregivers.Main areas: Not reported.Unmet needs (according to the caregivers): M=5 (S.D.=2.8) according to the caregiver.Main areas: Memory (57.5%), psychological distress (50%), daytime activities (47.5%). | No significant associations were found. |

| (32) Netherlands | In the community, attention in day centers or memory clinic. | Mental Health: Diagnosed dementia.Physical Health: Not reported. | N=236; 54.8% women; age M=79.8 (S.D.=7.6). | Informal Caregivers (n=322). Global Needs (M=9.6; S.D.=3.4) and unmet needs (M=1.7; S.D.=Not reported). Main areas Unmet Needs: daytime activities (13.1%), company (60.3%), memory (32.5%). | Met Needs: M=4.9 (S.D.=Not reported).Main areas: looking after home (69%), food (90%) and money management (51.4).Unmet Needs: M=0.5 (S.D.=Not reported).Main areas: Memory (10.2%), information (9.9%), company (5.4%). | Presents another type of dementia, compared to having a diagnosis of Alzheimer's, it is associated with an increase in UMN.Presenting a high burden on the caregiver is associated with an increase in UMN. |

| (3) England | In the community, primary attention. | Mental Health: Not reported.Physical Health: Not reported. | N=55; 62% Women; age M=81.5 (Median=85; range 75–95). | Health Professionals (N=55). Global Needs and unmet needs (M=Not reported). Main areas of Unmet Needs: daytime activities (17.3%), home (15.4%), mobility (13.5%).*A low number of informal caregivers participate, which prevents comparisons. | Met Needs: M=Not reported.Main areas: Physical Health (67.3%), food (46.2%), looking after home (42.3%).Unmet Needs: M=Not reported.Main areas: Psychological distress (19.2%), hearing/eyesight (21.2%), incontinence (17.3%). | Those types of association are not measured. |

M=mean; S.D.=standard deviation; p=p value; UMN=unmet needs.

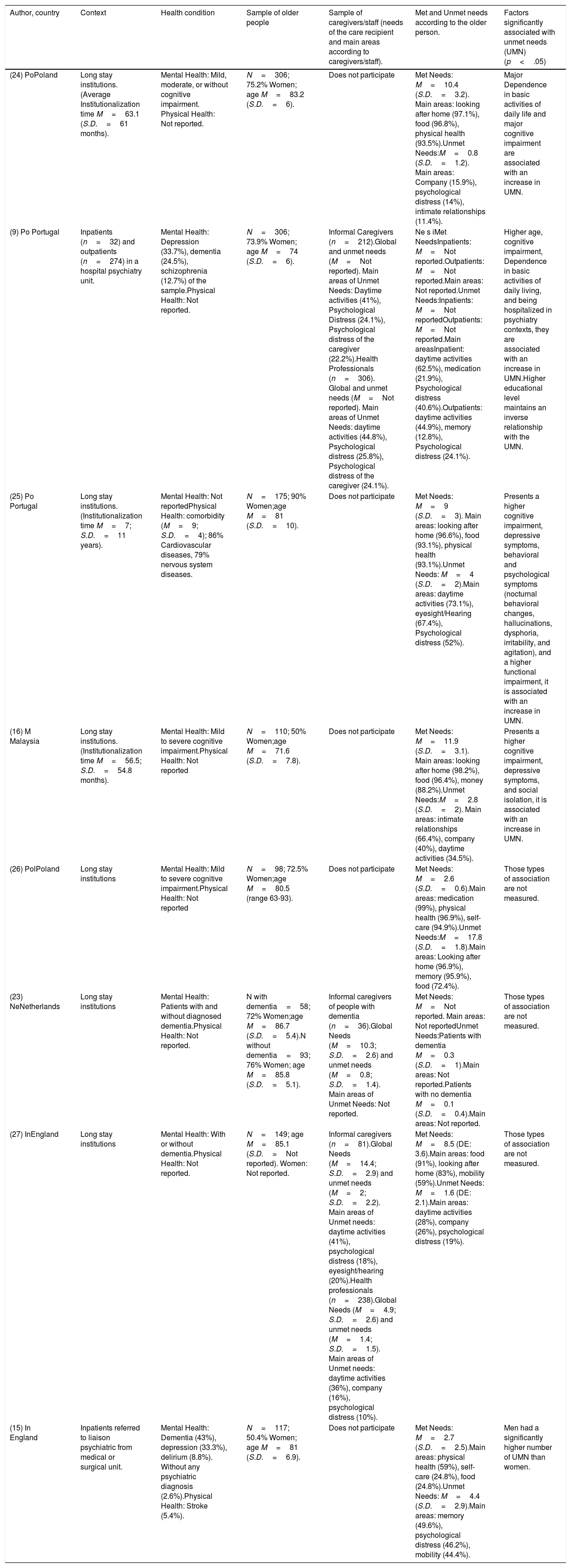

Results of selected studies with institutionalized older people sample.

| Author, country | Context | Health condition | Sample of older people | Sample of caregivers/staff (needs of the care recipient and main areas according to caregivers/staff). | Met and Unmet needs according to the older person. | Factors significantly associated with unmet needs (UMN) (p<.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (24) PoPoland | Long stay institutions.(Average Institutionalization time M=63.1 (S.D.=61 months). | Mental Health: Mild, moderate, or without cognitive impairment. Physical Health: Not reported. | N=306; 75.2% Women; age M=83.2 (S.D.=6). | Does not participate | Met Needs: M=10.4 (S.D.=3.2). Main areas: looking after home (97.1%), food (96.8%), physical health (93.5%).Unmet Needs:M=0.8 (S.D.=1.2). Main areas: Company (15.9%), psychological distress (14%), intimate relationships (11.4%). | Major Dependence in basic activities of daily life and major cognitive impairment are associated with an increase in UMN. |

| (9) Po Portugal | Inpatients (n=32) and outpatients (n=274) in a hospital psychiatry unit. | Mental Health: Depression (33.7%), dementia (24.5%), schizophrenia (12.7%) of the sample.Physical Health: Not reported. | N=306; 73.9% Women; age M=74 (S.D.=6). | Informal Caregivers (n=212).Global and unmet needs (M=Not reported). Main areas of Unmet Needs: Daytime activities (41%), Psychological Distress (24.1%), Psychological distress of the caregiver (22.2%).Health Professionals (n=306). Global and unmet needs (M=Not reported). Main areas of Unmet Needs: daytime activities (44.8%), Psychological distress (25.8%), Psychological distress of the caregiver (24.1%). | Ne s iMet NeedsInpatients: M=Not reported.Outpatients: M=Not reported.Main areas: Not reported.Unmet Needs:Inpatients: M=Not reportedOutpatients: M=Not reported.Main areasInpatient: daytime activities (62.5%), medication (21.9%), Psychological distress (40.6%).Outpatients: daytime activities (44.9%), memory (12.8%), Psychological distress (24.1%). | Higher age, cognitive impairment, Dependence in basic activities of daily living, and being hospitalized in psychiatry contexts, they are associated with an increase in UMN.Higher educational level maintains an inverse relationship with the UMN. |

| (25) Po Portugal | Long stay institutions.(Institutionalization time M=7; S.D.=11 years). | Mental Health: Not reportedPhysical Health: comorbidity (M=9; S.D.=4); 86% Cardiovascular diseases, 79% nervous system diseases. | N=175; 90% Women;age M=81 (S.D.=10). | Does not participate | Met Needs: M=9 (S.D.=3). Main areas: looking after home (96.6%), food (93.1%), physical health (93.1%).Unmet Needs: M=4 (S.D.=2).Main areas: daytime activities (73.1%), eyesight/Hearing (67.4%), Psychological distress (52%). | Presents a higher cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, behavioral and psychological symptoms (nocturnal behavioral changes, hallucinations, dysphoria, irritability, and agitation), and a higher functional impairment, it is associated with an increase in UMN. |

| (16) M Malaysia | Long stay institutions.(Institutionalization time M=56.5; S.D.=54.8 months). | Mental Health: Mild to severe cognitive impairment.Physical Health: Not reported | N=110; 50% Women;age M=71.6 (S.D.=7.8). | Does not participate | Met Needs: M=11.9 (S.D.=3.1). Main areas: looking after home (98.2%), food (96.4%), money (88.2%).Unmet Needs:M=2.8 (S.D.=2). Main areas: intimate relationships (66.4%), company (40%), daytime activities (34.5%). | Presents a higher cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and social isolation, it is associated with an increase in UMN. |

| (26) PolPoland | Long stay institutions | Mental Health: Mild to severe cognitive impairment.Physical Health: Not reported | N=98; 72.5% Women;age M=80.5 (range 63-93). | Does not participate | Met Needs: M=2.6 (S.D.=0.6).Main areas: medication (99%), physical health (96.9%), self-care (94.9%).Unmet Needs:M=17.8 (S.D.=1.8).Main areas: Looking after home (96.9%), memory (95.9%), food (72.4%). | Those types of association are not measured. |

| (23) NeNetherlands | Long stay institutions | Mental Health: Patients with and without diagnosed dementia.Physical Health: Not reported. | N with dementia=58; 72% Women;age M=86.7 (S.D.=5.4).N without dementia=93; 76% Women; age M=85.8 (S.D.=5.1). | Informal caregivers of people with dementia (n=36).Global Needs (M=10.3; S.D.=2.6) and unmet needs (M=0.8; S.D.=1.4). Main areas of Unmet Needs: Not reported. | Met Needs: M=Not reported. Main areas: Not reportedUnmet Needs:Patients with dementia M=0.3 (S.D.=1).Main areas: Not reported.Patients with no dementia M=0.1 (S.D.=0.4).Main areas: Not reported. | Those types of association are not measured. |

| (27) InEngland | Long stay institutions | Mental Health: With or without dementia.Physical Health: Not reported. | N=149; age M=85.1 (S.D.=Not reported). Women: Not reported. | Informal caregivers (n=81).Global Needs (M=14.4; S.D.=2.9) and unmet needs (M=2; S.D.=2.2). Main areas of Unmet needs: daytime activities (41%), psychological distress (18%), eyesight/hearing (20%).Health professionals (n=238).Global Needs (M=4.9; S.D.=2.6) and unmet needs (M=1.4; S.D.=1.5). Main areas of Unmet needs: daytime activities (36%), company (16%), psychological distress (10%). | Met Needs: M=8.5 (DE: 3.6).Main areas: food (91%), looking after home (83%), mobility (59%).Unmet Needs: M=1.6 (DE: 2.1).Main areas: daytime activities (28%), company (26%), psychological distress (19%). | Those types of association are not measured. |

| (15) In England | Inpatients referred to liaison psychiatric from medical or surgical unit. | Mental Health: Dementia (43%), depression (33.3%), delirium (8.8%). Without any psychiatric diagnosis (2.6%).Physical Health: Stroke (5.4%). | N=117; 50.4% Women; age M=81 (S.D.=6.9). | Does not participate | Met Needs: M=2.7 (S.D.=2.5).Main areas: physical health (59%), self-care (24.8%), food (24.8%).Unmet Needs: M=4.4 (S.D.=2.9).Main areas: memory (49.6%), psychological distress (46.2%), mobility (44.4%). | Men had a significantly higher number of UMN than women. |

M=mean; S.D.=standard deviation; p=p value; UMN=unmet needs.

All studies sought to identify the needs of the older person, and which factors could be associated with an increase in total or unmet needs. Nine studies analyzed the level of agreement between older people's own perspective of needs and their family caregiver views9,12,23,27–32 and five compared the older patient reports with those from health professionals.3,9,12,22,27 Finally, two studies aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of a version of the CANE questionnaire, as well as its feasibility.3,30

Regarding participants’ cognitive status, four studies recruited only older people without cognitive impairment,12,19,20,22 while ten explicitly focused on people with some degree of dementia.16,23,26–29,31,32 However, all the analyzed studies in this review excluded older people with advanced dementia or communication problems that prevented them from answering the questions of the CANE. In addition, due to age inclusion criteria of the present study, those studies focused on early onset dementia ended up being excluded. Four articles were centered on different mental health problems, such as depression, bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia9,12,21,22 and two studies specifically considered older people with physical health problems, such as fragility and arthritis.19,20 It should be noted that most of the articles did not report information on comorbidity and the general health status of the participant. Particularly, in the case of studies focusing on mental health problems, no morbidity was reported in the area of physical health. In the cases where morbidity was described,15,25 most of the participants presented a high level of comorbidity (diabetes, stroke, arthritis, cancer, chronic lung disease, among others).

Needs of community-dwelling dependent older peopleAt the studies of older people living in the community, it was found an average of unmet needs of this population within a range from 0.3 to 3.3. Differently, met needs showed greater variability (range from 3.5 to 10) (see Table 1). The studies focusing on people with dementia living in the community, who had mild to moderate cognitive impairment, showed higher mean of unmet needs, compared to those without cognitive impairment. Interestingly, the highest average of unmet needs (3.3) was found in older adults with dementia living in Chile.17

Needs of institutionalized older peopleThe studies on older people living in institutions showed a relatively high proportion of unmet needs, ranging from 0.1 to 17.8. However, met needs also tended to be high in this group (range: 2.6–11.9 points) (see Table 2). In addition, it was observed that samples were more homogeneous, where most participants presented mild to moderate cognitive impairment and a high number had at least one physical morbidity.

In the case of hospitalized persons, the average of unmet needs was 4.4 and the mean of met needs was 2.7. Nevertheless, the number of unmet needs decreased significantly after discharge.15

Most frequent met and unmet needsIn both, outpatient and institutionalized population, unmet needs were mainly found in the psychological and social dimensions (particularly in company, daytime activities and psychological distress), while most frequent met needs were found in the physical and environmental dimensions (food, physical health and looking after home). It is important to note that, even in populations where physical health problems were greater (physically fragile older people), the largest proportion of unmet needs were also found within the social and psychological dimensions.19,20

Level of agreement among the older person, their caregiver and/or a professionalIn general, it was observed that the care recipient and their formal or informal caregiver only reached moderate levels of agreement in the number of met and unmet needs.3,22,28,30 This disagreement seemed to increase in the case of older people with dementia, who tended to report fewer unmet needs compared to their formal and informal caregivers.9,23,27–29,31,32 This was not found in older people without dementia.30 On the other hand, one study focused on older people with major depression without cognitive impairment12 who reported more unmet needs than their caregivers and health professionals.

Even though informal caregivers did not necessarily point out the same number of needs as older people, they did report unmet needs mostly at the same dimensions (psychosocial needs).27,28,32 In contrast, health professionals not only did not identify the same needs as patients, but also omitted several needs of psychosocial nature (company, significant relationships, information, memory, psychological discomfort, hearing/vision and incontinence).3,22 Exceptionally, Houtjes et al.,12 whose sample had a diagnosis of major depression, found that health professionals demonstrated agreement with patients in social and psychological dimensions, but underestimated physical and environmental needs, reporting a smaller number of unmet needs compared to older people in these areas.

Factors associated with unmet needsStudies repeatedly indicated some factors that were significantly related (p<.05) to a lower or higher number of unmet needs. In the case of institutionalized older people (see Table 2), cognitive impairment and dependence on basic activities of daily life were associated with a significantly higher number of unmet needs. In contrast, for older people living in the community (see Table 1), contextual, socio demographics and caregiver aspects also emerged. For example, higher social isolation and lower quality of life of the older person, and also higher levels of caregiver burden and being a children of a person with dementia, was associated with a higher number of unmet needs.17,22,28,29,32 Throughout all the studies, the variable that was repeatedly found as a factor related to a high number of unmet needs was the presence of depressive symptoms in the older person. In contrast, higher educational levels of the older adult and greater social and emotional support were associated with a low frequency of unmet needs.30

DiscussionThis scoping review shows that the number of unmet needs tend to be higher on institutionalized older people compared to those living in the community. Even though the staff working at long term care facilities should have the skills required or at least have some training to address all types of needs, most unmet needs were psychosocial, while physical and environmental needs were mainly met. Nevertheless, this fact can also be explained because institutionalized people tend to exhibit a greater burden of morbidity, particularly cognitive impairment, which implies more needs to be addressed. In addition, a high number of unmet needs in institutionalized people can also be explained by the search of autonomy of the older person, who wishes to be part of the decision-making process and to receive individualized attention, expectation that may clash with the administrative and organizational demands of this context (as lack of time and resources).11,33

The review also shows a lack of agreement between the care recipient and their formal or informal caregivers, a phenomenon already observed in qualitative studies, which accounts for the subjective way in which needs are prioritized and perceived.5 A meta-analysis8 that explored the number of total needs of people with dementia, found that their informal caregivers reported higher level of total needs in 23 of the 24 areas of the CANE, with a significant disagreement in several of them. According to its authors, this discrepancy could be either due to real differences in perception, or because in some studies the participants had high levels of cognitive impairment so the CANE was answered only by the caregiver, who tend to report higher level of needs particularly when the care recipient had a more serious condition. In addition, the differences on needs reported between the care recipient and their caregivers can be explained as psychosocial needs tend to be more complex and dynamic so caregivers might have difficulties in assessing and addressing them.6 The fact that psychosocial needs were systematically less satisfied compared to environmental or physical needs is consistent with previous evidence showing that older people refer that the psychosocial aspects of their needs, such as facing the demands associated with aging, finding meaning and purpose, being accepted and respected, receiving accompaniment, among others; are usually ignored.5,11,34–36 Another possible explanation for the lack of agreement could be that, even though medical diagnoses tend to make some needs more obvious, they also make others needs less visible. For example, Houtjes et al.12 found that all participants in their study had major depression and, as expected, mental health professionals adequately identified their psychosocial needs, however, mental health workers reported fewer physical and environmental unmet needs compared to patients. The lack of coincidence between different care actors is an important issue considering that it could negatively affect patient's adherence to treatment, and the quality of the therapeutic relationship which depends largely on agreed goals.37,38

People with dementia tend to report more met and unmet needs on average than people without cognitive impairment, which shows how complex this disease is, and how it affects several aspects of a person's life.34,35 When compared to informal or formal caregivers, people with dementia report fewer needs. This could be explained for several reasons. First, cognitive impairment could affect individual's ability to detect their unmet needs. Second, while caregivers spot more “external” needs such as daytime activities,31 people with dementia may prioritize their needs differently, putting needs associated with their inner world (psychological discomfort) in first place. On the other side, reporting less needs may be due to a form of coping with the losses associated with dementia through denying or minimizing symptoms to maintain a sense of control.36 Likewise, it has been found that some older people in institutionalized contexts prefer to wait as long as possible to ask for help, for fear of being considered a burden and consequently discouraging needs report.33

According to this review, there is an association between mental health problems (especially depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment) and the presence of unmet needs, as well as informal caregiver's burden. Although it has not been established a causal relationship between mental health factors and unmet needs,39 this association could be explained as a mutual impact, where mental health problems represent a state of vulnerability in which the person experiences difficulties to meet their needs, which in turn can aggravate mental health problems of the older person and their informal caregivers.40

The CANE has been employed in a wide variety of countries allowing the exploration and comparison of needs and care provided on those contexts. For example, in this review the highest mean of unmet needs was found in older adults with dementia living in Chile.17 That country has an incipient formal care system where most families with a relative diagnosed with dementia do not have an optimal formal support network around this condition41 which consequently leads to a higher number of unmet needs when compared to other countries.

Within the limitations of this review, most of the selected studies were cross-sectional, with small convenience samples (with few exceptions). Therefore, the results do not imply causality and do not necessarily represent all dependent older people. Moreover, an assessment of the quality of the selected studies was not performed, which is necessary for further research. However, a strength of this review is associated with the consistency in the concept of needs assessed through the CANE instrument, which has good psychometric properties and was validated for most of the evaluated samples.

ConclusionThis review highlights the importance of making visible and includes older people's perspective on their needs, particularly those of a psychological and social nature. This becomes even more important in the case of older people who have some degree of dependence, depression or cognitive impairment, who should receive comprehensive care according to their level of autonomy, dignity and rights. Findings of this review indicate that professionals and informal caregivers could be assuming that older users have uniform needs, ignoring or minimizing some of them either because they move away from their own professional specialization or because they are more complex and difficult to cover in the daily routine. All these issues acquire great relevance, considering the association between unmet needs and their costs for the health system and public services.13 Further strategies and action plans which include these elements are required, as well as research that develops and supports interventions in this line.

FundingThis work was funded by the Vicerrectoría de Investigación, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Research Project: INTERDISCIPLINA II170053; the ANID - FONDECYT 1191726; the ANID - Millennium Science Initiative Program - ICS2019_024 and ICS13_005; and the ANID CONICYT Scholarship for postgraduate studies 22182112.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.