Health professionals are progressively drawing on the concept of frailty as a determinant of adverse surgical outcomes in of older adults. We aimed to determine the prevalence of frailty and the correlation between frailty and mortality among older adults admitted to the acute surgical unit.

Materials and methodsThis prospective cohort study was conducted in the acute general surgical unit over a two month period. We recruited 150 consecutive patients aged 65yrs and above. The modified frailty index was employed to measure frailty and the albumin levels on admission were obtained from electronic medical records. The patients were followed up for a period of thirty days.

ResultsWe found that more than 40% of the older adults admitted to the acute general surgical unit were frail and frailty was associated with higher rate of mortality at 30 days. Hypoalbuminemia was associated with a longer length of stay, higher rate of complications, and an increased likelihood of discharge to a rehabilitation facility. There was also a significant univariate correlation between frailty and the presence of hypoalbuminemia on admission.

ConclusionFrailty and hypoalbuminemia are common in older general surgical patients and predict the likelihood of some of the adverse outcomes relevant to older adults and health economy such as mortality, increased length of stay, rate of complications, and likelihood of discharge to a rehabilitation facility. Further studies should investigate a possible causal association between frailty and low albumin levels in an acute surgical setting.

Los profesionales de la salud se basan progresivamente en el concepto de fragilidad como determinante de los resultados quirúrgicos adversos de los adultos mayores. Se intentó determinar la prevalencia de la fragilidad y la correlación entre la fragilidad y la mortalidad entre los adultos mayores ingresados en la unidad de cirugía aguda.

Materiales y métodosEste estudio de cohorte prospectivo se llevó a cabo en la unidad de cirugía general aguda durante un período de 2 meses. Se reclutaron 150 pacientes consecutivos de 65 años y más. El índice de fragilidad modificada se empleó para medir la fragilidad y los niveles de albúmina en el momento del ingreso se obtuvieron a partir de historias clínicas electrónicas. Los pacientes fueron seguidos durante un período de 30 días.

ResultadosSe encontró que más del 40% de los adultos mayores ingresados en la unidad de cirugía general aguda eran frágiles, y la fragilidad se asoció con mayores tasas de mortalidad a los 30 días. La hipoalbuminemia se asoció con una mayor duración de la estancia, una tasa más alta de complicaciones y una mayor probabilidad de alta a un centro de rehabilitación. También hubo una correlación univariada significativa entre la fragilidad y la presencia de hipoalbuminemia en el ingreso.

ConclusiónLa fragilidad y la hipoalbuminemia son frecuentes en los pacientes de cirugía general de edad avanzada, y predicen la probabilidad de algunos de los resultados adversos relevantes para los adultos mayores y la economía de la salud como la mortalidad, el aumento de la duración de la estancia, la tasa de complicaciones y la probabilidad de alta en un centro de rehabilitación. Los estudios adicionales deben investigar una posible asociación causal entre la fragilidad y los niveles bajos de albúmina en un contexto quirúrgico agudo.

With the recent demographic changes in Australia, there has been an increase in the proportion of people aged 65 and above to 16% in 2016 from 14% in 2011,1 a trend which is expected to continue in the coming decades. Among the many consequences to health services of this demographic change is an increasing number of older patients that require surgical interventions, both elective and emergency.2 It is therefore necessary to devise or improve systems to predict which of these patients are likely to suffer adverse post-surgical outcomes. This will allow communication of potential risks, enabling patients to make informed choices in their care.2 Such assessments should identify particular vulnerabilities and care needs in both inpatient and post-discharge settings, and facilitate the wide scale changes in resource planning, which healthcare management must make to meet the needs of an ageing population.3 Two factors which are particularly important to assess in older adults in emergency and elective surgical settings are frailty and nutritional status.4

Frailty is a clinical state dictating increased dependency and/or mortality under stressors.5 A significant proportion of the geriatric population is thought to be frail, although the percentage varies depending on the tool used and the population studied. A recent systematic review that analysed 21 community based studies identified that 10.7% of community dwelling older adults are frail.6 Frail individuals have decreased physiological reserve making them vulnerable to adverse health outcomes. Identification of patients as frail also has a knock-on effect of predicting risk of other common geriatric syndromes, including poor mobility, recurrent falls, osteoporosis and dementia.7 In the community setting, frailty has been shown to be associated with recurrent falls,8 increased probability of hip fractures9 and death.10 Frailty has also been evaluated in various surgical settings, and has been shown to predict adverse outcomes, duration of in-patient stay, likelihood of post-discharge,11 and death.12

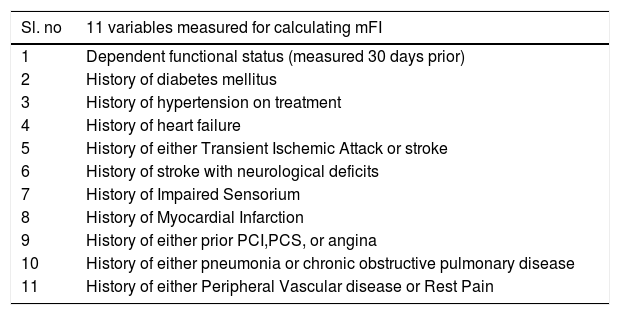

Researchers and practitioners across multiple clinical settings have suggested various tools for the assessment of frailty. A modified Frailty Index (mFI) was subsequently introduced where only 11 variables (Table 1) are used to calculate the index (as a proportion of the total).13 A score of 0 is the lowest possible score indicating the absence of frailty, whereas a score of 1 is the highest possible score indicating maximum frailty. Following research comparing the physical frailty phenotype and the deficit accumulation model, a score of ≥0.27 has been established as the cut off between frail and non frail groups.14 This has since been applied in published research.15,16 The mFI has advantages over the earlier model in that the time and resources necessary to complete it are significantly reduced,13 but it retains its worth as a validated tool for assessment of frailty and predictor of poor surgical, clinical and post-discharge outcomes.17 In particular, it has been shown to be useful in predicting the outcomes following orthopaedic,18 and emergency general surgery.19

Modified frailty index with 11 variables.

| Sl. no | 11 variables measured for calculating mFI |

|---|---|

| 1 | Dependent functional status (measured 30 days prior) |

| 2 | History of diabetes mellitus |

| 3 | History of hypertension on treatment |

| 4 | History of heart failure |

| 5 | History of either Transient Ischemic Attack or stroke |

| 6 | History of stroke with neurological deficits |

| 7 | History of Impaired Sensorium |

| 8 | History of Myocardial Infarction |

| 9 | History of either prior PCI,PCS, or angina |

| 10 | History of either pneumonia or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| 11 | History of either Peripheral Vascular disease or Rest Pain |

Albumin constitutes nearly half of the total plasma proteins and is synthesised in the liver. Serum albumin levels less than 35gm/L are considered low.20 Among the reasons that serum albumin levels should be evaluated is that low levels can be a strong indicator of malnutrition.21 Studies have revealed malnutrition is present in approximately one fifth of geriatric inpatients, and is linked with duration of inpatient stay, in-hospital mortality rates, the likelihood discharge to institutionalised care22 and adverse rehabilitation outcomes in general.23 While serum albumin levels correlate reasonably well with the clinical assessment of nutritional status,24 it has a low specificity mainly due to the non-nutritional causes of hypoalbuminemia.25 Albumin is a negative acute phase reactant and the measured serum levels can also be skewed by the patient's hydration levels and the presence of hepatic and renal impairment.26 Researchers have demonstrated an association between hypoalbuminemia and major peri-operative complications following total knee arthroplasty27 and revision of total knee.28 A recent systematic review which examined the postoperative outcomes in older general surgery patients identified serum albumin as one of the predictors of complicated post-operative course,29 while another study identified an association between hypoalbuminemia and increased mortality in patients undergoing surgery for intestinal perforation.30 We hypothesised that high mFI and hypoalbuminemia negatively impact mortality rates and clinical outcomes among older adults in an acute general surgical setting. The study was conducted in the principal tertiary hospital in South Metropolitan Area Health Service (SMAHS), Perth, Western Australia. Total inpatient care globally is increasingly taken up by the elderly population, with 49% accounted for by patients aged 60 and over.31

MethodsApproval was requested and obtained from the institutional Quality Improvement Committee utilising the Governance, Evidence, Knowledge, Outcomes system (GEKO – Quality Activity 26419).

We recruited consecutive patients aged 65+ who were admitted to the acute general surgical unit in the study centre during the months of May and June 2018. The following exclusion criteria were applied: patients re-admitted during the study period; patients with malignancy; patients undergoing elective surgery; and patients with a known diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome or hepatic synthetic dysfunction.

An Excel spreadsheet was created for data collection and analysis. Data on demographic characteristics were principally obtained from iSoft Clinical Manager (iCM) and the electronic medical records (EMR). iCM is a software that is available in all public hospitals in WA and one can access demographic details, pathology & imaging results and discharge summaries of all registered patients. EMR has copies of observation charts and inpatient progress notes. Both archives were mined for information on age, gender, place of birth, residence details and principal diagnoses (classified in five groups: pancreatic-biliary pathology, bowel obstruction/perforation, gastrointestinal bleeding, intra-abdominal inflammation, hernias and others).

The mFI was calculated for each patient using the 11 variables as described earlier (Appendix-1) and those patients with an mFI score of ≥0.27 were considered frail. iCM yielded data on serum albumin levels at the time of admission and hypoalbuminemia is defined as levels less than <35g/L. Data regarding management (interventions or non-operative) were recorded to the Excel sheet following daily reviews. The prospective nature of the project allowed studying multiple outcomes simultaneously for each group and outcomes such as length of stay, discharge destination, inpatient complications and mortality for each group were monitored through close follow up during their stay in hospital. Any complication that the patients suffered during the stay was recorded into the Excel spread sheet, with particular attention to post-operative infections and delirium. Delirium had to be diagnosed and documented by the treating medical staff for it to be included in this study. 30 day mortality was defined as death from any cause within 30 days of admission to the hospital. Some of the out of hospital deaths were updated on iCM; if this information was not available on iCM, phone calls were made to the general practitioner or to the residential care facility after 30 days. 30 day re-admission was defined as any unplanned admission through emergency department due to any reason within 30 days of discharge. The data on re-admissions to any public hospital in WA were captured from iCM.

Statistical analysisData are reported as mean or median for continuous variables and as proportion for categorical variables. Associations between frailty and patient outcomes, age, gender and hypoalbuminaemia were investigated using the Chi-square test, Fisher's exact test or univariate logistic regression. Analysis was performed using Stata 15 (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC) and significance was set at p<0.05.

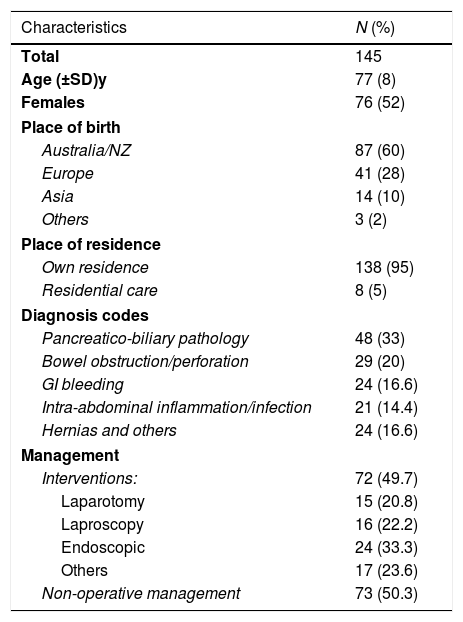

ResultsOne hundred and fifty potentially eligible patients were identified, 5 of which were subsequently deemed ineligible (as they received a new diagnosis of malignancy during the current admission) resulting in a final sample of 145 patients. 79 participants (55%) were aged 76-plus years, out of which 53 (36.5%) were aged between 76 and 85 years, and the remaining 26 (18%) being 86 or over. Mean respondent age was 77 (SD 8) years. 52% were females and 60% were born in Australia.95% of the cohort presented from private residence. Further patient characteristics with regards to the diagnoses and management are presented in Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 145 |

| Age (±SD)y | 77 (8) |

| Females | 76 (52) |

| Place of birth | |

| Australia/NZ | 87 (60) |

| Europe | 41 (28) |

| Asia | 14 (10) |

| Others | 3 (2) |

| Place of residence | |

| Own residence | 138 (95) |

| Residential care | 8 (5) |

| Diagnosis codes | |

| Pancreatico-biliary pathology | 48 (33) |

| Bowel obstruction/perforation | 29 (20) |

| GI bleeding | 24 (16.6) |

| Intra-abdominal inflammation/infection | 21 (14.4) |

| Hernias and others | 24 (16.6) |

| Management | |

| Interventions: | 72 (49.7) |

| Laparotomy | 15 (20.8) |

| Laproscopy | 16 (22.2) |

| Endoscopic | 24 (33.3) |

| Others | 17 (23.6) |

| Non-operative management | 73 (50.3) |

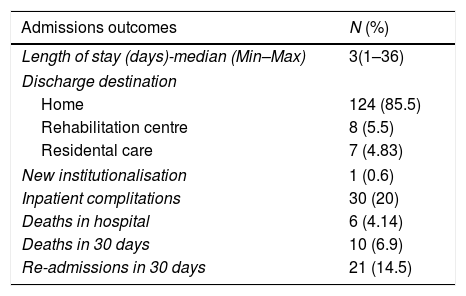

Data on the measured outcomes for the total study population are summarised in Table 3. Median duration of inpatient stay was three days and the data concerning inpatient stays were skewed with a large number of patients with shorter stays and relatively fewer with longer stays. 5.5% were discharged to a rehabilitation centre, of whom a single patient was later institutionalised.

Outcomes following the admission.

| Admissions outcomes | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Length of stay (days)-median (Min–Max) | 3(1–36) |

| Discharge destination | |

| Home | 124 (85.5) |

| Rehabilitation centre | 8 (5.5) |

| Residental care | 7 (4.83) |

| New institutionalisation | 1 (0.6) |

| Inpatient complitations | 30 (20) |

| Deaths in hospital | 6 (4.14) |

| Deaths in 30 days | 10 (6.9) |

| Re-admissions in 30 days | 21 (14.5) |

20% (n=30) of the cohort experienced complications during inpatient stay with chest infection being the most frequent (30%). Other complications suffered included ileus, delirium, acute kidney injury, cardio-vascular complications, pressure injury and falls. There was no significant association detected between complications and either age or gender.

Inpatient mortality rate was 4% (n=6), with sepsis and multi organ failure being the commonest causes of death. The 30 day mortality rate was 7% (n=10). 14.5% (n=21) were readmitted within 30 days of discharge.

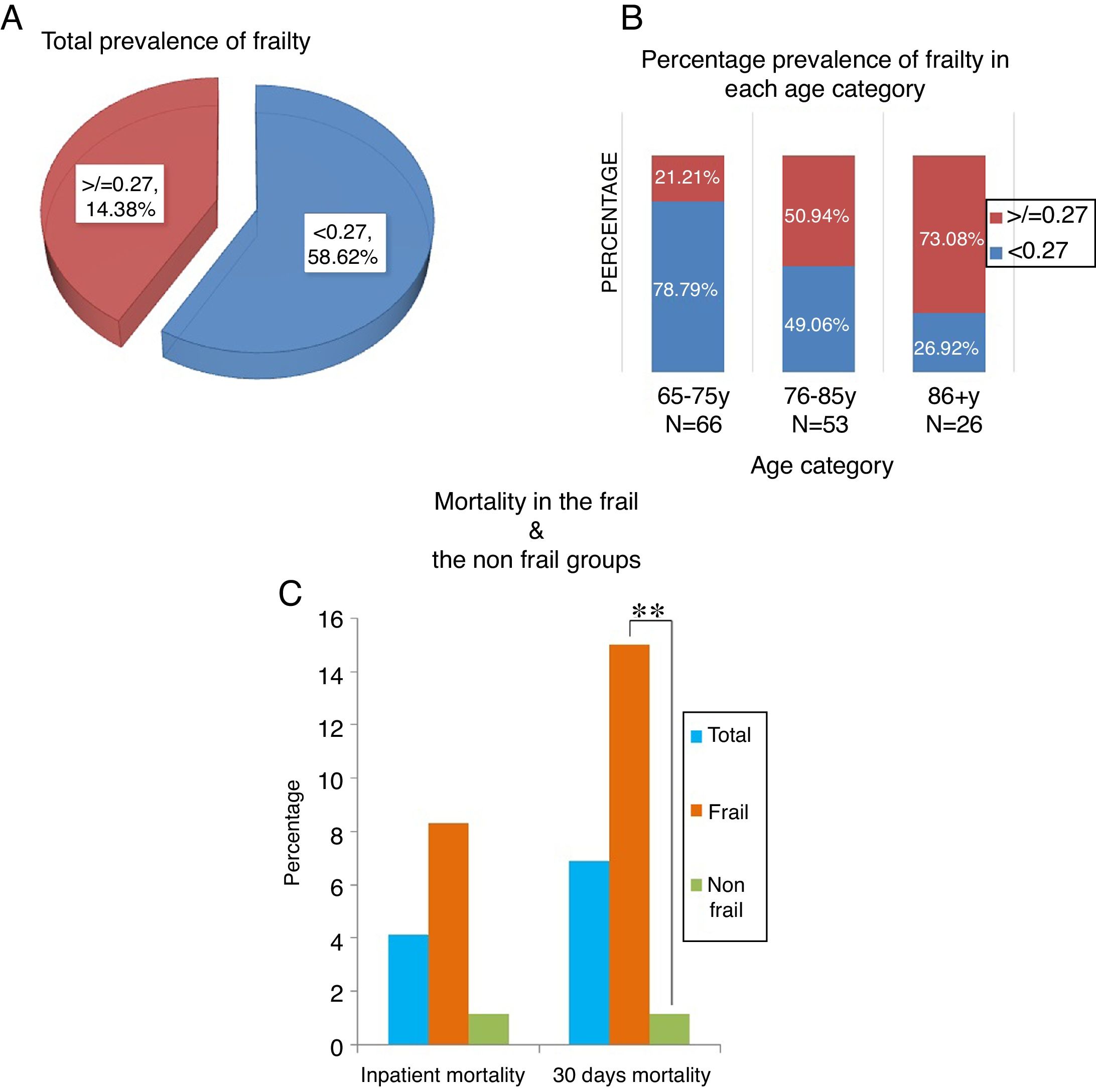

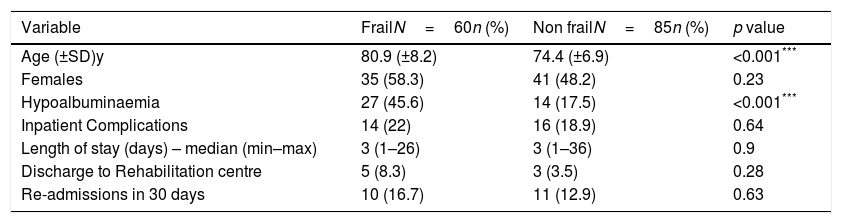

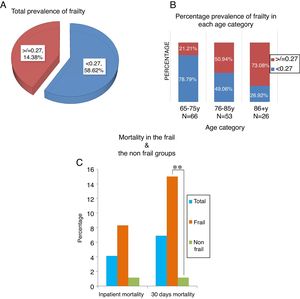

Prevalence of frailtyBased on the mFI score, 60 (41.4%) patients were classified as frail. No difference in the prevalence of frailty (Fig. 1A) was detected between genders (p=0.23) (Table 4), however the differences between age categories were, as expected, significant (p<0.001) (Fig. 1(B)).

Patient characteristics and other outcomes in frail and non-frail groups.

| Variable | FrailN=60n (%) | Non frailN=85n (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (±SD)y | 80.9 (±8.2) | 74.4 (±6.9) | <0.001*** |

| Females | 35 (58.3) | 41 (48.2) | 0.23 |

| Hypoalbuminaemia | 27 (45.6) | 14 (17.5) | <0.001*** |

| Inpatient Complications | 14 (22) | 16 (18.9) | 0.64 |

| Length of stay (days) – median (min–max) | 3 (1–26) | 3 (1–36) | 0.9 |

| Discharge to Rehabilitation centre | 5 (8.3) | 3 (3.5) | 0.28 |

| Re-admissions in 30 days | 10 (16.7) | 11 (12.9) | 0.63 |

A statistically significant difference was observed in the 30 day mortality between the frail and non-frail groups in this study (15% Vs 1.2% p=0.002) (Fig. 1:(B)), whereas no such difference was identified on comparing the inpatient mortality rates (8.3% vs 1.2%, p=0.082).

Association between frailty and other outcomesThere was no statistically significant association between frailty and other outcomes such as inpatient complications, length of stay, discharge to rehabilitation centre or re-admission rates in this study (Table 4).

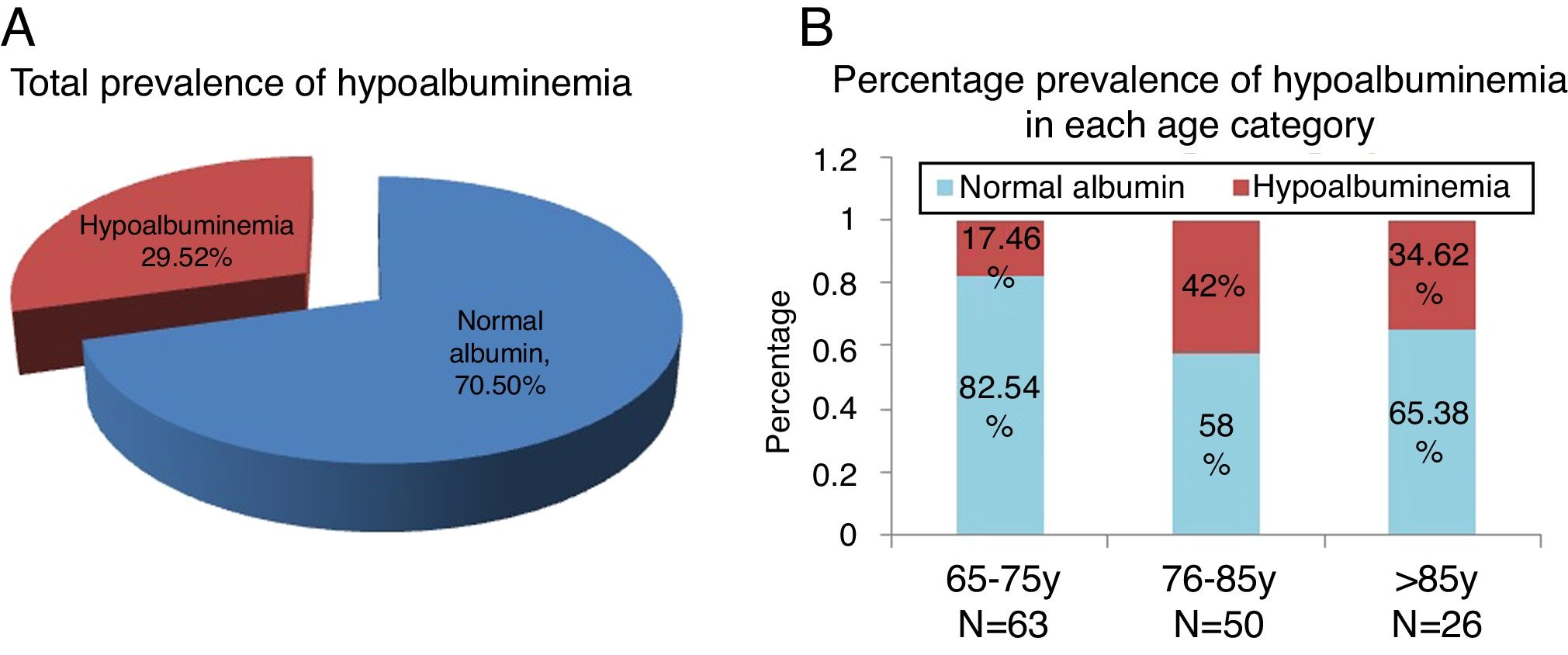

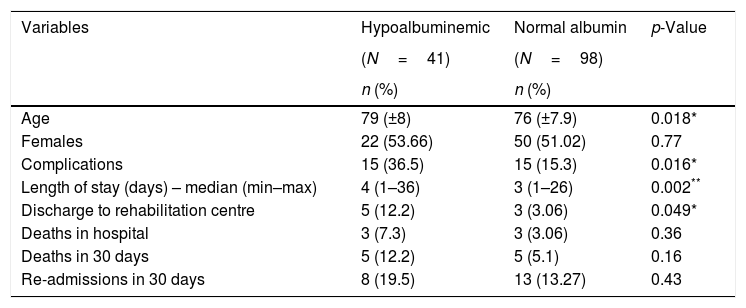

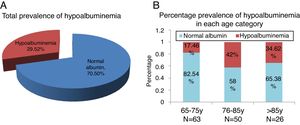

Prevalence of Hypoalbuminaemia and its association with various outcomesData was missing on albumin levels for six of the cohort. Of the 139 patients for whom such data was available, 41 (29.5%) (Fig. 2A) had hypoalbuminemia on admission, with the condition most prevalent among those aged between 76 and 85 years (Fig. 2(B)). No significant difference in the prevalence of hypoalbuminemia could be detected between genders.

It was notable that complications rates were higher among hypoalbuminemic patients than those with normal albumin levels (36.5% vs 15.3%, p=0.016) (Table 5). Similarly, hypoalbuminemic patients had longer inpatient stays (4 vs 3 days, p=0.002)and were more likely to be discharged to a rehabilitation centre before returning home (12.2% vs 3.06%, p=0.049). There was no significant association between hypoalbuminemia and mortality or re-admission rates (Table 5).

Patient characteristics and other outcomes in hypoalbuminemic and non-hypoalbuminemic groups.

| Variables | Hypoalbuminemic | Normal albumin | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=41) | (N=98) | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age | 79 (±8) | 76 (±7.9) | 0.018* |

| Females | 22 (53.66) | 50 (51.02) | 0.77 |

| Complications | 15 (36.5) | 15 (15.3) | 0.016* |

| Length of stay (days) – median (min–max) | 4 (1–36) | 3 (1–26) | 0.002** |

| Discharge to rehabilitation centre | 5 (12.2) | 3 (3.06) | 0.049* |

| Deaths in hospital | 3 (7.3) | 3 (3.06) | 0.36 |

| Deaths in 30 days | 5 (12.2) | 5 (5.1) | 0.16 |

| Re-admissions in 30 days | 8 (19.5) | 13 (13.27) | 0.43 |

A statistically significant association was detected between frailty and hypoalbuminemia, with hypoalbuminemia detected in 46% of frail patients compared to 17.5% of non-frail patients (p<0.001). A univariate analysis revealed that low albumin levels were four times more likely to be present in frail than non-frail patients (OR=3.98, 95%CI: 1.8–8.6, p<0.001). Multivariate analysis could not be carried out because of the small sample size and the confounding factors.

DiscussionWith the ageing population and the increasing number of older adults requiring both elective and emergency surgery, the impact of ageing on surgical outcomes has become a subject of recent attention. Frailty has been increasingly recognised as a predictor of adverse surgical outcomes in older adults and multiple tools have been developed to suit various clinical settings.

Our study demonstrated that frailty is associated with an increased 30 day mortality among geriatric acute surgical patients. We also identified that, using the mFI tool, over 40% of the older patients admitted to the acute surgical unit could be categorised as ‘frail’. This figure is slightly higher compared to the results of a recent meta-analysis (10–37%) on general surgical patients,32 which might be due to the difference in the frailty assessment tool employed. The fact remains, however, that frailty is associated with age, and has a clear impact on both peri- and post-operative outcomes. It is therefore vital for practitioners to undertake a thorough pre-operative assessment of such patients; however, the imperatives of emergency surgery often mean the time is lacking to do so.

Modified Frailty index is based on the deficit accumulation model of frailty and most of the data required are already part of the routine pre-operative assessment. This obviates the need to bring in specialised personnel or equipment to measure factors such as grip strength and walking speed. mFI combines the speed, ease of use and sensitivity13 and helps to rapidly identify frail patients in emergency circumstances.

Identifying at-risk patients not only to alert surgeons and other clinicians to possible vulnerabilities but also aid in the discussion of potential outcomes with the patients and their carers so that informed decisions and choices can meaningfully be made. Topics such as goals of care, likely discharge destination and potential need for rehabilitation can all be brought into the conversation so that over all care can be better understood. The advantages to starting such conversations early in the process and ensuring communication among the entire team, including the patient and her/his carers, have been discussed by many researchers, and are associated with improvements in functional status.33

Identification of frail older adults also unveils a potential role for geriatricians in the acute surgical ward who can intervene in patients undergoing expectant management and in selected emergency pre-operative situations to optimise care. Certainly, their expertise can better support the frail patients to cope with the surgical stress in the post-operative setting, and they can play an imperative role in prevention, early identification and timely management of complications. They can also facilitate and govern the multidisciplinary input to assist with recovery and discharge.

Our study also showed a strong correlation between low serum albumin levels and adverse post-operative outcomes, including risk of complications, longer duration of in-patient stay and the likelihood of discharge to rehabilitation centres. Despite the debate over the usefulness of serum albumin levels as an indicator of malnutrition, hypoalbuminemia regardless of its cause has been demonstrated to be associated with adverse outcomes in older adults.34 Hypoalbuminemia is associated with an increase in medical complications and poor functional outcome in patients admitted to rehabilitation units.35 Further research is needed to determine whether detailed nutritional assessment and interventions may offer improved outcomes in the older adults admitted to such units.

The link between frailty and hypoalbuminemia in the older adults remains unclear, although it seems associations between the two exist. Research has shown that hypoalbuminemia is associated with higher mortality in frail older adults.36 Patients with low albumin frequently suffer sarcopenia21,34 which itself is a hallmark of frailty. Institutionalised frail older patients have been demonstrated to have lower albumin levels compared to their non-frail counterparts37 and has been linked to weakened immune function.38 Our study demonstrated that low albumin levels are more likely to be present in frail than in non- frail individuals in an acute surgical setting. Given the limitations due to the small sample size and confounders in this study, we recommend that further research in a larger sample should be undertaken to validate this. Moreover, it is also recommended that investigations are done to identify whether there is a causal association between frailty and hypoalbuminemia in acute surgical patients.

Limitations of the studyAs the present study was originally conceived of as a pilot, a small cohort was researched, which then permitted only a similarly small number of sub-set analyses and multivariate analysis. Moreover, the cohort was also heterogeneous, as it included all patients aged 65 and over who met the criteria for inclusion, regardless of diagnosis on admission. The demographic data was obtained from electronic medical records and so the data collection might have been limited by accuracy of documentation and coding errors. A further concern is that albumin is an acute phase reactant. Even when the levels on presentation were only considered in order to exclude the impact of changes due to an extended in-patient stay, these may not be purely reflective of the baseline levels. Data on out of hospital deaths may be incomplete as this was obtained from the electronic medical records, residential care facility or from general practitioners. Finally, this study was performed in patients presenting to an acute surgical unit and may not be generalisable beyond similar cohort.

FundingThis study was not an external funded project.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank co-workers for all assistance.