HF elderly patients are underrepresented in Sacubitril/Valsartan HF trials, and the effect of S/V in real-life patients with advanced age is unknown. The aim of this study was to evaluate the use and safety of S/V in a real-word cohort of elderly patients.

MethodsWe performed a prospective registry of patients who started S/V in clinical practice. We compared baseline characteristics, adverse events during follow-up and causes of S/V withdrawal according to age.

ResultsA total of 427 patients started treatment with S/V: 222 (52.0%)<70 years old, 140 (32.8%) between 70 and 79 and 65 (15.2%)≥80. During a mean follow-up of 7.0±0.1months S/V was well tolerated, with no age-related differences in adverse events (26.8%, 25.9%, 23.1% respectively; p=0.83). Symptomatic hypotension tended to be more frequent in the elderly (19.8%, 25.6%, 33.3% respectively; p=0.17). The withdrawal of S/V was more frequent in younger patients (14.4%, 10.0%, 4.6% respectively; p=0.05) and related to poor prognosis (HR 13.51, 95% CI 3.22–56.13, p<0.001).

ConclusionsSacubitril/Valsartan is useful and safe in elderly people with HF-rEF in real-life clinical practice, and withdrawal is associated to poor prognosis. The doses achieved are lower in elderly people.

Los pacientes ancianos con IC están sub-representados en los ensayos de IC sacubitril/valsartán (S/V), y se desconoce el efecto del S/V en pacientes de la vida real con edad avanzada. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar el uso y la seguridad del S/V en una cohorte de pacientes ancianos.

MétodosSe realizó un registro prospectivo de los pacientes que iniciaron el S/V en la práctica clínica. Se compararon las características iniciales, los eventos adversos durante el seguimiento y las causas de la abstinencia del S/V según la edad.

ResultadosUn total de 427 pacientes iniciaron el tratamiento con S/V: 222 (52,0%)<70 años, 140 (32,8%) entre 70-79 años y 65 (15,2%)≥80 años. Durante un seguimiento medio de 7,0±0,1 meses, el S/V fue bien tolerado, sin diferencias en los eventos adversos relacionados con la edad (26,8, 25,9 y 23,1%, respectivamente; p=0,83). La hipotensión sintomática tendió a ser más frecuente en los ancianos (19,8, 25,6 y 33,3%, respectivamente; p=0,17). El retiro del S/V fue más frecuente en pacientes más jóvenes (14,4, 10,0 y 4,6%, respectivamente; p=0,05) y se relacionó con un pronóstico precario (CRI: 13,51; IC del 95%: 3,22-56,13; p<0,001).

ConclusionesEl sacubitril/valsartán es útil y seguro en personas de edad avanzada con HF-rEF en la práctica clínica de la vida real, y la abstinencia se asocia con un pronóstico deficiente. Las dosis alcanzadas son más bajas en las personas mayores.

The prevalence of heart failure (HF) increases with age1–4 being one of the leading causes of hospitalization and death in the elderly.5–7 Although age of people first diagnosed of HF is about 80 years old,7–9 mean age in HF clinical trials is still below 65 and elderly people is underrepresented.10,11 Moreover, drugs with impact in survival are frequently underused in this population due to lack of evidence, more adverse effects, higher prevalence of comorbidities and age-related decrease in adherence.12–14

Sacubitril/Valsartan (S/V) has been recently included in clinical practice guidelines because it reduced the risk of both cardiovascular mortality and HF hospitalization in symptomatic HF patients with reduced ejection fraction (HF-rEF) included in Prospective Comparison of ARNI [Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor] with ACEI [Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibitor] to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure Trial (PARADIGM-HF).11 A sub-analysis of this trial showed that patients over 65 years old also benefit from S/V, with similar safety.15 However, the lower incidence of the primary outcome in elderly patients included in PARADIGM-HF compared to other clinical trials and the restricted inclusion criteria makes it necessary to evaluate S/V in real-word patients with advanced age. The aim of this study is to describe the clinical characteristics and prognosis of elderly patients with HF-rEF who initiated S/V, and also to evaluate the use and safety of the drug in real-life clinical practice.

MethodsWe performed a multicentric registry including all outpatients who began treatment with S/V between October 2016 and March 2017 in ten hospitals of Madrid Autonomic Comunity.16,17 The exclusion criteria were: drug initiation during hospital admission, because there were not evidence in that moment, and not signing the informed consent.

Patients were divided into 3 age categories: <70, 70–79 and ≥80 years old. For each category, different variables were analyzed: (a) medical history, vital signs, functional class and visits to the emergency room or hospital admission in the previous 6 months; (b) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF); (c) previous treatment as well as devices at the time of inclusion; (d) blood test parameters; (e) aspects related to S/V: starting dose, washing period, dose modifications and/or discontinuation during the titration. The follow-up and up-titration was made according to physician judgement and clinical practice in each hospital.

The patients was followed-up during 6 months, and the occurrence of events was analyzed: (a) death, emergency room visits or hospital admission; (b) S/V adverse effects (those established in PARADIGM-HF and TITRATION)11,18: symptomatic arterial hypotension, hyperkalemia (K>5.5mEq/L), deterioration of renal function (end-stage renal disease or worsening of the estimated filtration rate (eGFR) of at least 50% compared to the values of onset after initiating S/V or a decrease in eGFR below 30mL/min/1.73m2) or angioedema; and (d) maximum tolerated dose and drug withdrawal. Adverse events were considered during the whole follow up or until the drug withdrawal.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the General University Hospital Gregorio Marañón of Madrid, Spain.

Statistical methodsQuantitative variables are shown as mean and standard deviation and categorical ones as frequencies and percentages. Continuous quantitative variables were compared using Student's T-test or the sum of Wilcoxon ranges in nonparametric data, and categorical variables with the χ2 test and Fischer's exact test. A significance level of 0.05 (bilateral) was established for all statistical tests.

A logistic regression model was performed to determine the independent predictors of S/V suspension during follow-up, using the sequential inclusion and exclusion method, with inclusion threshold p<0.05 and exclusion greater than 0.1. The survival analysis was carried out according to the Kaplan–Meier method, analyzing mortality. A proportional hazards regression model (Cox) was developed to analyze the independent predictors of mortality in follow-up. Both the logistic and Cox regression models were adjusted according to sex, age, history of ischaemic heart disease, eGFR, previous treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, previous treatment with beta-blockers, previous treatment with MRA, NTproBNP, NYHA functional class, admission in the previous 6 months, ICD, CRT and the appearance of events related to the drug. The analysis was performed with STATA 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

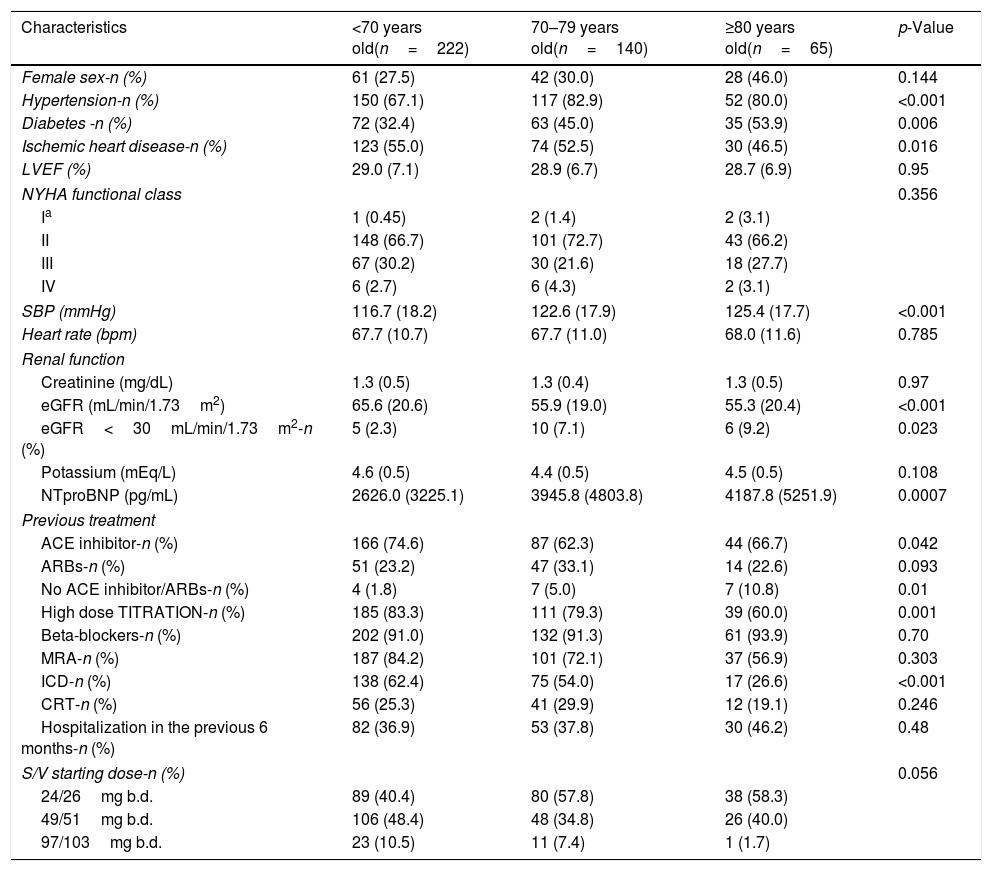

ResultsA total of 427 outpatients were included, with a mean age of 68.1±12.4 years old. 222 were <70 years old, 140 between 70–79, and 65≥80. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Elderly patients has higher rate of hypertension, diabetes and ischaemic heart disease. Age-realted differences were also found in systolic blood pressure (SBP), eGFR and NTproBNP values. The percentage of ICD decreased with age. All patients completed the follow-up (mean 7.0±0.1 months).

Baseline characteristics and starting dose of Sacubitril/Valsartan according to age.

| Characteristics | <70 years old(n=222) | 70–79 years old(n=140) | ≥80 years old(n=65) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex-n (%) | 61 (27.5) | 42 (30.0) | 28 (46.0) | 0.144 |

| Hypertension-n (%) | 150 (67.1) | 117 (82.9) | 52 (80.0) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes -n (%) | 72 (32.4) | 63 (45.0) | 35 (53.9) | 0.006 |

| Ischemic heart disease-n (%) | 123 (55.0) | 74 (52.5) | 30 (46.5) | 0.016 |

| LVEF (%) | 29.0 (7.1) | 28.9 (6.7) | 28.7 (6.9) | 0.95 |

| NYHA functional class | 0.356 | |||

| Ia | 1 (0.45) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (3.1) | |

| II | 148 (66.7) | 101 (72.7) | 43 (66.2) | |

| III | 67 (30.2) | 30 (21.6) | 18 (27.7) | |

| IV | 6 (2.7) | 6 (4.3) | 2 (3.1) | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 116.7 (18.2) | 122.6 (17.9) | 125.4 (17.7) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 67.7 (10.7) | 67.7 (11.0) | 68.0 (11.6) | 0.785 |

| Renal function | ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.5) | 0.97 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 65.6 (20.6) | 55.9 (19.0) | 55.3 (20.4) | <0.001 |

| eGFR<30mL/min/1.73m2-n (%) | 5 (2.3) | 10 (7.1) | 6 (9.2) | 0.023 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.4 (0.5) | 4.5 (0.5) | 0.108 |

| NTproBNP (pg/mL) | 2626.0 (3225.1) | 3945.8 (4803.8) | 4187.8 (5251.9) | 0.0007 |

| Previous treatment | ||||

| ACE inhibitor-n (%) | 166 (74.6) | 87 (62.3) | 44 (66.7) | 0.042 |

| ARBs-n (%) | 51 (23.2) | 47 (33.1) | 14 (22.6) | 0.093 |

| No ACE inhibitor/ARBs-n (%) | 4 (1.8) | 7 (5.0) | 7 (10.8) | 0.01 |

| High dose TITRATION-n (%) | 185 (83.3) | 111 (79.3) | 39 (60.0) | 0.001 |

| Beta-blockers-n (%) | 202 (91.0) | 132 (91.3) | 61 (93.9) | 0.70 |

| MRA-n (%) | 187 (84.2) | 101 (72.1) | 37 (56.9) | 0.303 |

| ICD-n (%) | 138 (62.4) | 75 (54.0) | 17 (26.6) | <0.001 |

| CRT-n (%) | 56 (25.3) | 41 (29.9) | 12 (19.1) | 0.246 |

| Hospitalization in the previous 6 months-n (%) | 82 (36.9) | 53 (37.8) | 30 (46.2) | 0.48 |

| S/V starting dose-n (%) | 0.056 | |||

| 24/26mg b.d. | 89 (40.4) | 80 (57.8) | 38 (58.3) | |

| 49/51mg b.d. | 106 (48.4) | 48 (34.8) | 26 (40.0) | |

| 97/103mg b.d. | 23 (10.5) | 11 (7.4) | 1 (1.7) | |

ACE inhibitor: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs: angiotensin receptor antagonists; b.d.: twice a day; bpm: beats per minute; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fracion; MRA: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; NYHA: New York Heart Association; SBP: systolic blood pressure; S/V: Sacubitril/Valsartan.

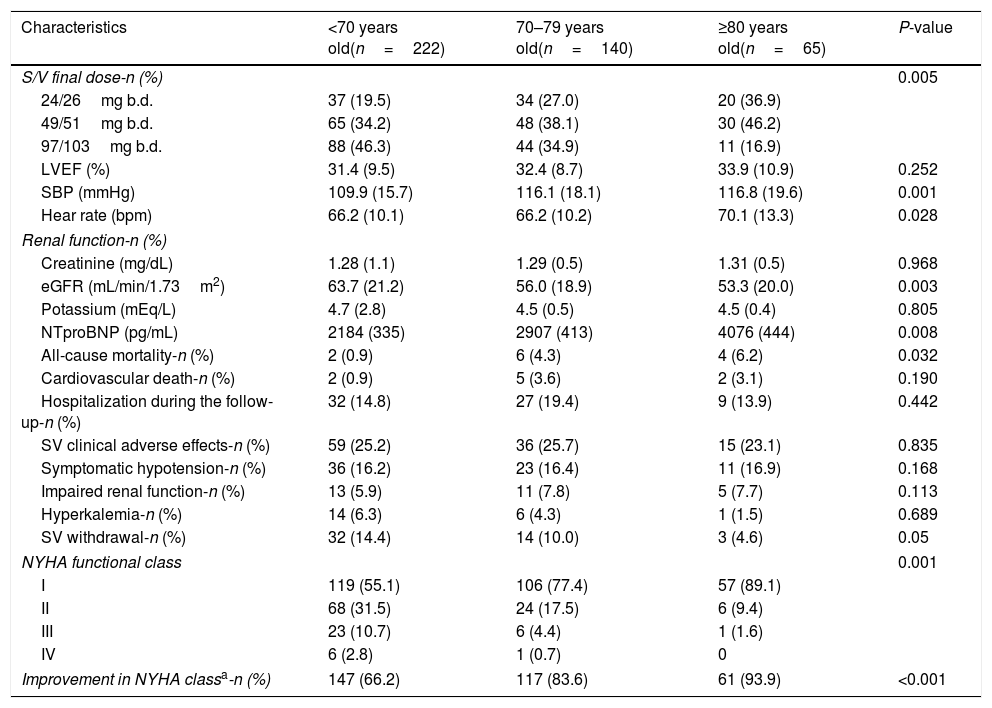

The most frequent starting dose of S/V was 24/26mg b.d. in patients over 70 years old and 49/51mg b.d. in younger ones. Also, most patients>80 years old were still receiving 24/26mg b.d. at the end of follow-up, with higher doses achieved in younger patients. Table 2 shows the main adverse events during the follow-up. The withdrawal rate of S/V decreased with age, and there were no differences in adverse effects in every age category according to S/V withdrawal. At the end of follow-up, we found age-related differences in SBP, heart rate (HR), eGFR, NTproBNP and NYHA functional class.

Data at the end of follow-up according to age.

| Characteristics | <70 years old(n=222) | 70–79 years old(n=140) | ≥80 years old(n=65) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/V final dose-n (%) | 0.005 | |||

| 24/26mg b.d. | 37 (19.5) | 34 (27.0) | 20 (36.9) | |

| 49/51mg b.d. | 65 (34.2) | 48 (38.1) | 30 (46.2) | |

| 97/103mg b.d. | 88 (46.3) | 44 (34.9) | 11 (16.9) | |

| LVEF (%) | 31.4 (9.5) | 32.4 (8.7) | 33.9 (10.9) | 0.252 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 109.9 (15.7) | 116.1 (18.1) | 116.8 (19.6) | 0.001 |

| Hear rate (bpm) | 66.2 (10.1) | 66.2 (10.2) | 70.1 (13.3) | 0.028 |

| Renal function-n (%) | ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.28 (1.1) | 1.29 (0.5) | 1.31 (0.5) | 0.968 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 63.7 (21.2) | 56.0 (18.9) | 53.3 (20.0) | 0.003 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.7 (2.8) | 4.5 (0.5) | 4.5 (0.4) | 0.805 |

| NTproBNP (pg/mL) | 2184 (335) | 2907 (413) | 4076 (444) | 0.008 |

| All-cause mortality-n (%) | 2 (0.9) | 6 (4.3) | 4 (6.2) | 0.032 |

| Cardiovascular death-n (%) | 2 (0.9) | 5 (3.6) | 2 (3.1) | 0.190 |

| Hospitalization during the follow-up-n (%) | 32 (14.8) | 27 (19.4) | 9 (13.9) | 0.442 |

| SV clinical adverse effects-n (%) | 59 (25.2) | 36 (25.7) | 15 (23.1) | 0.835 |

| Symptomatic hypotension-n (%) | 36 (16.2) | 23 (16.4) | 11 (16.9) | 0.168 |

| Impaired renal function-n (%) | 13 (5.9) | 11 (7.8) | 5 (7.7) | 0.113 |

| Hyperkalemia-n (%) | 14 (6.3) | 6 (4.3) | 1 (1.5) | 0.689 |

| SV withdrawal-n (%) | 32 (14.4) | 14 (10.0) | 3 (4.6) | 0.05 |

| NYHA functional class | 0.001 | |||

| I | 119 (55.1) | 106 (77.4) | 57 (89.1) | |

| II | 68 (31.5) | 24 (17.5) | 6 (9.4) | |

| III | 23 (10.7) | 6 (4.4) | 1 (1.6) | |

| IV | 6 (2.8) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | |

| Improvement in NYHA classa-n (%) | 147 (66.2) | 117 (83.6) | 61 (93.9) | <0.001 |

b.d.: twice a day; bpm: beats per minute; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA: New York Heart Association; SBP: systolic blood pressure; S/V: sacubitril/valsartan.

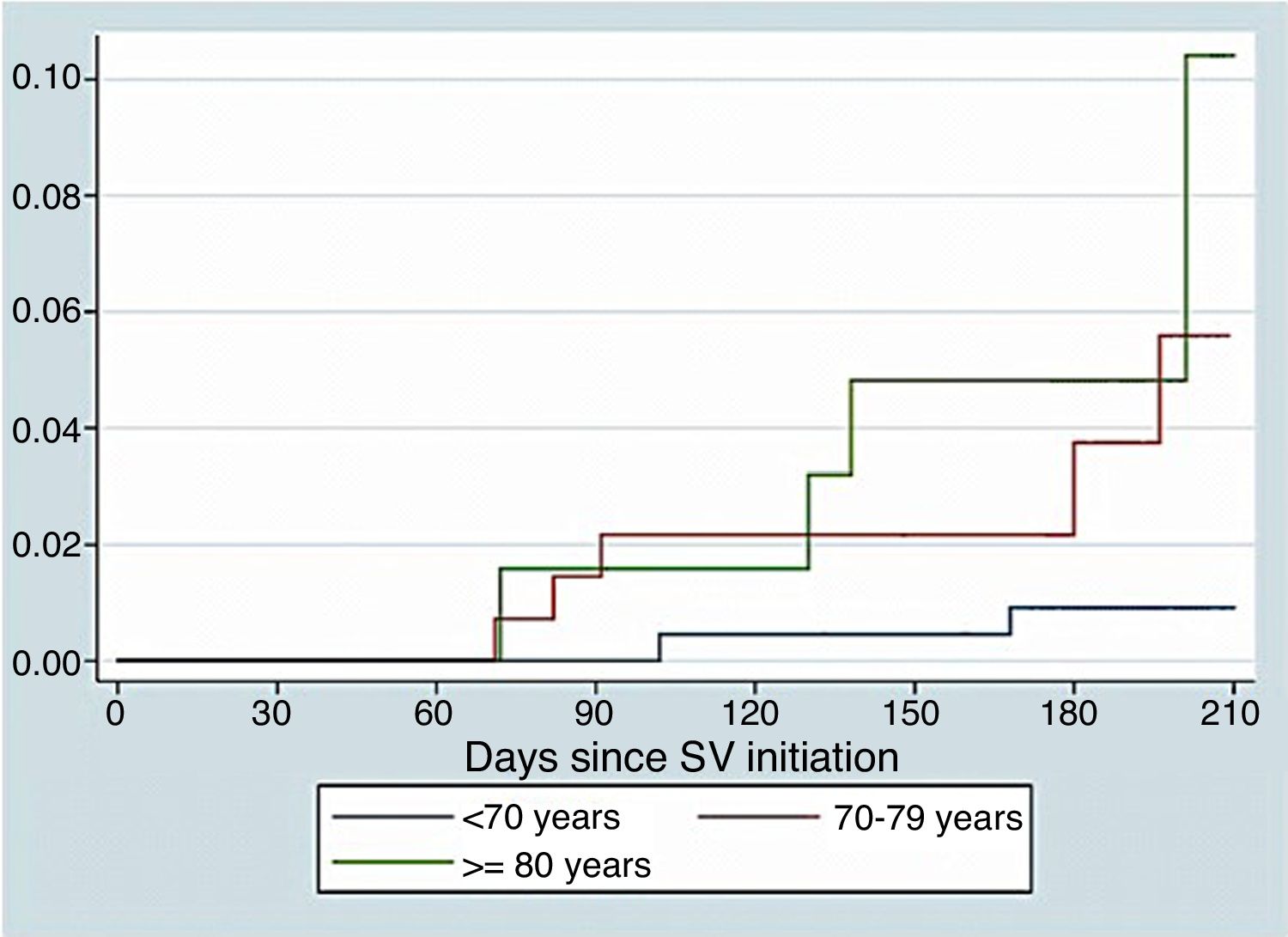

Fig. 1 show survival curves according to age. We identified as independent predictors of S/V discontinuation age (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.91–0.98, p=0.001) and events related to S/V (OR 5.19, 95% CI 2.1–12.85, p<0.001). In the adjusted Cox regression model, both discontinuation of S/V (HR 13.51, 95% CI 3.22–56.13, p<0.001) and age (HR 1.21, 95% CI 1.12–1.34, p=0.002) were found to be independent predictors of mortality.

DiscussionTo the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies published about S/V use in clinical practice in a cohort of elderly patients with HF-rEF. According to our results, S/V is safe in elderly people and can be used similarly to younger patients.

Patients included in our registry had severely impaired left ventricular ejection fraction and were mostly in NYHA II, even those>80 years old. Advanced-age patients who started S/V were more often female, with more comorbidities (i.e. diabetes or renal disease) and less ischaemic heart disease. Also, they had higher SBP, with lower eGFR and higher natriuretic peptides. Pre-trial treatment was very similar across age categories, except in MRA, with lower doses in elderly patients. As expected, ICD were less frequent with age.

The most frequent starting dose of S/V was 24/26mg b.d. in all age groups. After titration, older patients achieved lower doses, with less than 20% of patients with the higher dose in those over 80 years old. The explanation could be that physicians were more carefull in up-titration in elderly patients because of its high risk of adverse effects. Also, there were not a significant decrease of systolic blood pressure (SBP) or renal deterioration after up-titration. Although clinical adverse effects were similar in all groups, symptomatic hypotension was the most common one, specially in older people. However, S/V discontinuation for any reason was more frequent in younger people.

Our patients were older than those included in previous S/V trials and registries,4,8,11 but their baseline characteristics were similar to PARADIGM-HF patients.15 NYHA II was the most common functional class also in patients>80 years old,15 although it is difficult to assess functional class in elderly population due to several factors such as comorbidity or frailty. Compared to other registries and trials11,14,15 our patients had similar rate of beta-blocker use and higher rate of MRA, except on elderly patients, who nonetheless had a similar prescription to that achieved in PARADIGM-HF (56.9% and 57% respectively). The reason for not using MRA in elderly could be related to the appearance of adverse effects such as hyperkaliemia and renal function deterioration, more frequent due to comorbidities and age. However the withdrawal due to these causes was uncommon, even in elderly. In our registry, similarly to PARADIGM-HF,11,15,19 symptomatic hypotension was the most frequent adverse effect and it frecuency increased with age, although that did not lead to a higher rate of S/V withdrawal in elderly patients.

The rate of hypotension was very similar in those who maintained or discontinued S/V across all age categories, so it was possible that the discontinuation due to symptomatic hypotension was also related to other factors such as HF patient profile or advance disease. Elderly patients, with a high risk of presenting adverse effects, specially symptomatic hypotension, have been protected by a careful low-dose initiation, slowly up-titration and close follow-up, thus increasing the chance of maintaining S/V.18,20

S/V has shown to improve survival and physical and social activity, also in elderly and multimorbidity patients.15,21–24 In our registry, S/V discontinuation was related to a worse prognosis in terms of hospitalization and mortality, also in older patients. S/V treatment was associated to NYHA class improvement, and patients who maintain S/V experienced a greater improvement. Thus, our data suggest that adverse effects must be carefully evaluated in elderly people before S/V withdrawal.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, it was not a randomized study. Secondly, the adherence to all HF drugs different to S/V was not assessed at the end of follow-up. Besides, functional class was evaluated with NYHA, and we did not perform a specific quality of life assessment. Besides, only some comobidities were recorded, and the number of patients included in the group above 80 years old was small, but this is the first real-life study including people in this age range. Thus, it is necessary to confirm these results in large randomized clinical trials specifically performed in elderly patients.

In conclusion, S/V is safe in elderly people in a real-world cohort of HF-rEF patients and can be used similar to younger ones. The appearance of adverse effects which can lead to S/V discontinuation can be avoided with an approptiate patients selection and medication carefully up-titration. The doses achieved in elderly people are lower than in younger ones.

Conflict of interestNone of the authors has a conflict of interest.

All the author take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.