To establish the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescription (PIP) in older people with advanced dementia, monitored by a Geriatric Home Care Unit (GHC), as well as the associated risk factors and costs.

MethodsCommunity-dwelling patients ≥65 years with an advanced dementia diagnosis (GDS-FAST≥7a) and poor 1-year vital prognosis (Frail-VIG≥0.6) were included. Pharmacotherapy history was reviewed retrospectively, collecting functional and cognitive status, on the first GHC visit, of patients assessed January 2016–January 2019. Potentially inappropriate medication was defined following STOPP-Frail criteria.

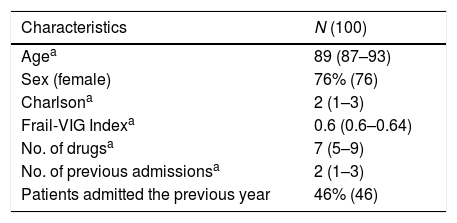

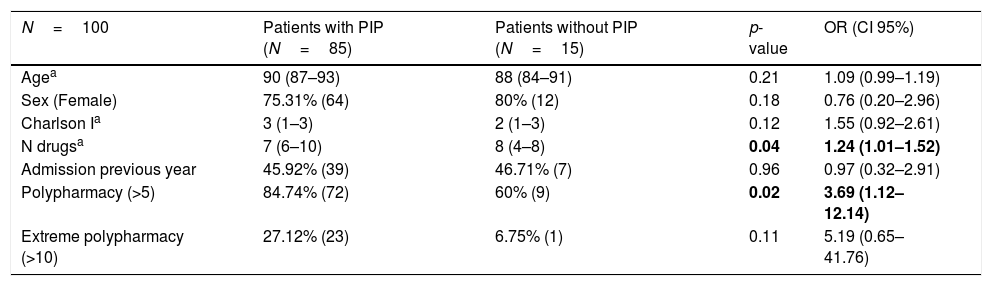

Results100 patients included (76% women, 89.15±5.8 years). Total medications prescribed 760 (7.63±3.4 drugs per patient). 85% patients were given at least one drug considered to be PIP. 26% (196) of the total drugs registered were PIPs. Patients who were prescribed an inappropriate drug showed a higher number of total prescribed drugs (7.92±3.42 vs 6.00±2.24; p 0.04) and a higher frequency of polypharmacy (84.7% vs 60%; p 0.025). Risk of receiving inappropriate medication increased by 24% for each additional drug prescribed (OR 1.24; 95% CI 1.01–1.52; p 0.04). The costs associated with PIP were 113.99 euros per 100 patients/day; 41,606.35 euros per 100 patients/year.

ConclusionsPrescription of PIP to community-dwelling patients with severe dementia and poor vital prognosis is common and is associated with high economic impact in this population group.

Establecer la prevalencia de medicamentos potencialmente inapropiados (MPI) en pacientes mayores de 65 años con diagnóstico de demencia avanzada en seguimiento en la Unidad de Atención Geriátrica Domiciliaria, así como los factores de riesgo y los costes asociados a su prescripción.

Material y métodosSe incluyó a pacientes mayores de 65 años con diagnóstico de demencia en estadio avanzado (GDS-FAST≥7a) y pobre pronóstico vital al año (Fragil-VIG≥0,6). Se revisó de forma retrospectiva la historia farmacoterapéutica, el estado funcional y cognitivo en la primera visita realizada por la Unidad de Atención Geriátrica Domiciliaria de pacientes valorados entre enero de 2016 y enero de 2019. La MPI se definió siguiendo los criterios STOPP-Frail.

ResultadosSe incluyó a un total de 100 pacientes (76% mujeres; 89,15±5,8 años). El total de medicamentos prescritos fue 760 (7,63±3,4 fármacos por paciente). Un 85% de los pacientes presentó al menos un fármaco considerado como MPI. El 26% (196) del total de fármacos registrados fueron MPI. Comparado con los pacientes sin MPI, los pacientes con algún fármaco inapropiado presentaron mayor número de fármacos prescritos (7,92±3,42 vs. 6,00±2,24; p 0,04) y mayor frecuencia de polifarmacia (84,7 vs. 60%; p 0,025). Por cada fármaco adicional prescrito el riesgo de recibir una medicación inapropiada se incrementaba un 24% (OR 1,24; IC 95%: 1,01-1,52; p 0,04). Los costes asociados a la prescripción de MPI fueron 113,99 euros por 100 pacientes/día; 41.606,35 euros por 100 pacientes/año.

ConclusionesLa prescripción de MPI en los pacientes con demencia grave y pobre pronóstico vital que residen en la comunidad es frecuente y asocia un elevado impacto económico en este grupo poblacional.

The prevalence of dementia, especially Alzheimer's disease, is growing exponentially, currently affecting approximately 50 million people worldwide. Its incidence is estimated at 9.9 million new cases per year.1

Advanced dementia is the most profound phase of cognitive and physical impairment, characterised by an inability to recognise relatives, limited oral expression, inability to walk around independently and to perform basic daily activities, dysphagia, and double incontinence. In elderly patients it is the main cause of disability and dependence. McCarthy et al. concluded, in a retrospective study, that patients with advanced dementia experienced similar symptoms and presented similar care needs to patients with other terminal diseases such as cancer, recognising it as a terminal process with palliative need.2

Polypharmacy, defined as the use of five or more drugs, is highly prevalent in the older population3,4 and is associated not only with increased risk of drug interactions, but also with a higher risk of functional impairment, hospitalisation and mortality.5

Inappropriate prescription occurs when a drug's associated risks outweigh its potential benefits for any given patient. A drug may be inappropriate because it has been prescribed without clear indication based on scientific evidence, because it has been prescribed for an inadequate period of time or because it has a high risk of adverse drug reaction (ADR). Failing to prescribe a drug recommended for prevention or treatment of a disease is also inappropriate and entails unnecessary costs.6

Older patients in end-of-life situations are a particularly vulnerable population with a high risk of suffering adverse effects from drug treatments, as a result of the frequent coexistence of various factors such as polypharmacy, functional impairment, cachexia, malnutrition, comorbidity and variations in body composition. Several clinical trials have shown a decreased risk of adverse effects when withdrawing medications. In particular, a study by palliative care specialists in which inappropriate drugs were withdrawn from older patients resulted in an improvement in quality of life, while also reducing adverse events and associated costs.7

It would be reasonable to conduct a detailed review of drug treatment in older people with advanced dementia, personalising the objectives for each patient, and trying to ensure well-being and quality of life, instead of trying to prevent problems in the medium to long term.8,9 The prior wishes of the patients, their families and caregivers would play a key role in defining treatment goals and care needs.

There are different tools for deprescribing patients with advanced dementia, such as Holmes, Parsons and SHELTER criteria. Likewise, the Irish group that developed the STOPP-START criteria has proposed a tool called STOPP-Frail criteria,10 aimed specifically at improving drug prescription in people receiving palliative care. We found multiple studies evaluating the prevalence of PIP in institutionalised patients. These patients are often frail and have multiple diseases, high drug consumption and poor life prognosis.11 There is high prevalence of PIP in this population group, which is especially striking in the final year of life.12 However, we have not found any studies concerning community-dwelling older people with advanced dementia and palliative needs. Hence, the interest in determining the prevalence of PIP in this population group, as well as the economic impact of these potentially futile or dispensable treatments. Accordingly, the aims of this study are:

- •

To establish the prevalence of PIP by applying the STOPP-Frail criteria in community-dwelling patients over 65 years of age with an advanced dementia diagnosis, monitored by the Geriatric Home Care Unit (GHC) of the Hospital Central de la Cruz Roja, as well as the risk factors associated with their prescription.

- •

To determine the costs associated with those treatments.

A single-centre retrospective observational study was conducted in patients being monitored by the Geriatric Home Care Unit (GHC) of a supporting University Hospital (Hospital Central de la Cruz Roja San José y Santa Adela, HCCR). The patients included were aged ≥65 years old, assessed by the GHC, between January 2016 and January 2019, with an advanced dementia diagnosis of any type (Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST) ≥7a) as well as poor vital prognosis for the coming year, defined as a Frail-VIG Index ≥0.6. Patients with a history of active oncological disease were excluded. The following variables were collected:

- •

Frail-VIG Index (F-VIG-I).13

- •

Comorbidity measured using the Charlson index.

- •

Number of hospital admissions in the last year.

- •

Number of drugs prescribed (including on-demand medication, nutritional supplements, vitamin supplements, etc.).

- •

Pharmacological history at the time of assessment, taking into account the presence of polypharmacy (>5 drugs) or extreme polypharmacy (>10 drugs).

A multidisciplinary team of three pharmacists and four doctors from the Geriatric Service conducted this study, carrying out the tasks of evaluating clinical histories and collecting data, with subsequent recording and reviewing of each patient's usual treatment, identifying PIPs according to STOPP-Frail criteria (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions in Frail adults with limited life expectancy).10 A1 and A2 criteria were excluded as compliance was not evaluated in our study.

CostsIn order to calculate the economic burden we took into account the direct costs of medications and dietary products financed by the National Health System (NHS), those prescribed chronically as well as on demand. Acute treatments (treatments with an end date at the time of data collection) were excluded.

The cost per day was calculated using the Dispensed Price for Maximum Quantity (DPMQ) for the NHS in March 2019 (Order SCB/1244/2018). If the drug did not have a DPMQ, the financing price was used. Similarly, for nutritional supplements, the cost per day was calculated on the basis of maximum financing amounts, obtained from Royal Decree 1205/2010. Patient contribution was not taken into account in any case. Hospital dispensing medication was not excluded from the analysis. Food supplements (e.g., cranberry, resveratrol, etc.) were not included. For on-demand medications, the price of one dose/day was included. The costs are expressed in euros. The results provided in this study are euros per 100 patients per day, and euros per 100 patients per year. The average cost of PIPs per patient/day was calculated.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using SPSS© version 26. Differences in the distribution of categorical variables were compared using Pearson Chi-square test (χ2) with Yates correction and continuous variables using Mann-Whitney U for independent samples. A comparison was made between those patients with at least one potentially inappropriate drug according to STOPP-Frail criteria and those without any drug meeting these criteria. Univariate logistic regression was performed to establish association between age, sex, Charlson Index, number of drugs, admission in the previous year, polypharmacy and the presence of potentially inappropriate medication, calculating the Odds Ratio with its 95% confidence interval. A probability of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Alfonso X el Sabio University in Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid (Spain).

ResultsA total of 100 patients were included, of which 76% were women. The baseline characteristics of the sample are summarised in Table 1, consisting of older people with high comorbidity as well as functional and cognitive dependence. Polypharmacy was present in 57% of the sample with 24% displaying extreme polypharmacy.

The percentage of patients with any PIP identified by STOPP-Frail criteria was 85% (85 out of 100 patients). Based on these criteria, one PIP was found in 21 patients (21%), two PIPs in 33 patients (33%), three PIPs in 17 patients (17%), four PIPs in 12 patients (12%) and five PIP in 2 patients (2%).

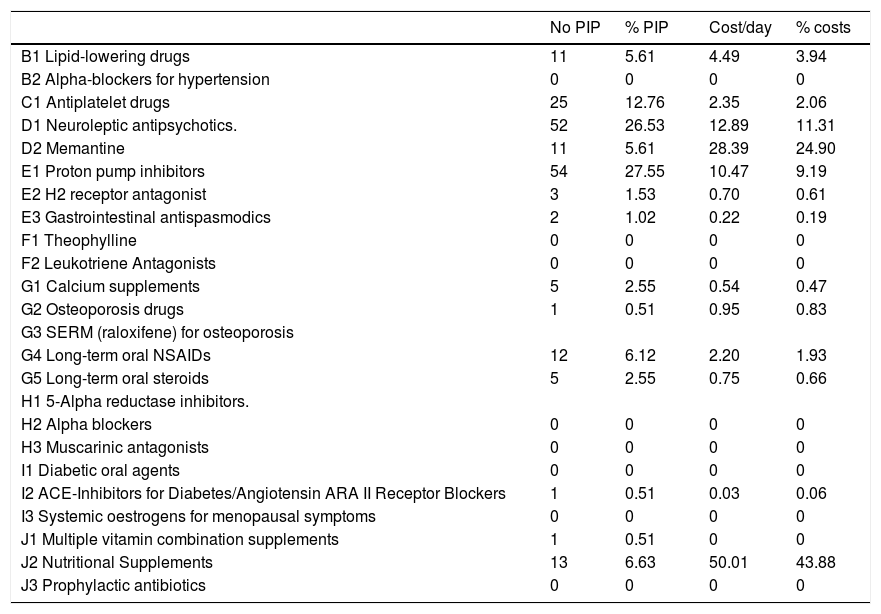

Type of medicationOut of the total number of drugs (760), 25.8% (196) were considered PIPs. The distribution by groups is shown in Table 2. The most frequently found PIPs were: proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) at full therapeutic dose (27.55%), neuroleptics (26.53%), antiplatelet drugs in primary cardiovascular prevention (12.76%), prophylactic nutritional supplements (6.63%), lipid-lowering drugs (5.61%) and memantine (5.61%).

Potentially inappropriate medication and associated cost.

| No PIP | % PIP | Cost/day | % costs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 Lipid-lowering drugs | 11 | 5.61 | 4.49 | 3.94 |

| B2 Alpha-blockers for hypertension | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C1 Antiplatelet drugs | 25 | 12.76 | 2.35 | 2.06 |

| D1 Neuroleptic antipsychotics. | 52 | 26.53 | 12.89 | 11.31 |

| D2 Memantine | 11 | 5.61 | 28.39 | 24.90 |

| E1 Proton pump inhibitors | 54 | 27.55 | 10.47 | 9.19 |

| E2 H2 receptor antagonist | 3 | 1.53 | 0.70 | 0.61 |

| E3 Gastrointestinal antispasmodics | 2 | 1.02 | 0.22 | 0.19 |

| F1 Theophylline | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F2 Leukotriene Antagonists | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| G1 Calcium supplements | 5 | 2.55 | 0.54 | 0.47 |

| G2 Osteoporosis drugs | 1 | 0.51 | 0.95 | 0.83 |

| G3 SERM (raloxifene) for osteoporosis | ||||

| G4 Long-term oral NSAIDs | 12 | 6.12 | 2.20 | 1.93 |

| G5 Long-term oral steroids | 5 | 2.55 | 0.75 | 0.66 |

| H1 5-Alpha reductase inhibitors. | ||||

| H2 Alpha blockers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| H3 Muscarinic antagonists | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I1 Diabetic oral agents | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I2 ACE-Inhibitors for Diabetes/Angiotensin ARA II Receptor Blockers | 1 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| I3 Systemic oestrogens for menopausal symptoms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| J1 Multiple vitamin combination supplements | 1 | 0.51 | 0 | 0 |

| J2 Nutritional Supplements | 13 | 6.63 | 50.01 | 43.88 |

| J3 Prophylactic antibiotics | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 3 shows the influence of age, sex, and comorbidity measured using Charlson index, number of drugs prescribed, number of hospital admissions during the previous year and the influence of polypharmacy and extreme polypharmacy on the increased risk of receiving potentially inappropriate medication. No statistically significant association was observed between the presence of PIP and age and sex. In comparison to patients without PIP, patients with an inappropriate drug had a higher number of prescribed drugs and a higher frequency of polypharmacy. Patients also exhibited a tendency to present greater comorbidity and extreme polypharmacy, even though statistically significant differences were not found. The risk of receiving inappropriate medication according to STOPP-Frail criteria increased by 24% for each additional drug prescribed (OR=1.24, 95% CI=1.01–1.52; p=0.04).

Factors associated with potentially inappropriate prescription medication.

| N=100 | Patients with PIP (N=85) | Patients without PIP (N=15) | p-value | OR (CI 95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 90 (87–93) | 88 (84–91) | 0.21 | 1.09 (0.99–1.19) |

| Sex (Female) | 75.31% (64) | 80% (12) | 0.18 | 0.76 (0.20–2.96) |

| Charlson Ia | 3 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.12 | 1.55 (0.92–2.61) |

| N drugsa | 7 (6–10) | 8 (4–8) | 0.04 | 1.24 (1.01–1.52) |

| Admission previous year | 45.92% (39) | 46.71% (7) | 0.96 | 0.97 (0.32–2.91) |

| Polypharmacy (>5) | 84.74% (72) | 60% (9) | 0.02 | 3.69 (1.12–12.14) |

| Extreme polypharmacy (>10) | 27.12% (23) | 6.75% (1) | 0.11 | 5.19 (0.65–41.76) |

For the whole sample, the costs associated with PIP were 113.99 euros per 100 patients/day; 41,606.35 euros per 100 patients/year. The average cost linked to the PIP pattern in our sample amounts to 1.14 euros/patient/day.

In terms of the impact of each drug group included as potentially inappropriate with respect to overall expenditure, the highest rate was for nutritional supplements (43.88%), followed by memantine (24.9%), neuroleptics (11.31%), PPIs (9.19%) and lipid-lowering agents (3.94%).

DiscussionIn our study we found a high prevalence of PIP after applying STOPP-Frail criteria (85% of the sample), similar to the prevalence found in other studies such as Lavan et al.,14 which presents figures of around 91.2%, and Curtin et al.15 with an 80% prevalence.

Other previous studies, such as those by O'Sullivan et al.16 and Ryan et al.,17 display prevalence rates using STOPP criteria, of 70% and 59.8% respectively. These lower figures could be explained by the fact that in these last two studies, STOPP criteria were applied to detect PIP in the older population in general, as opposed to our population which consists of frail older people with multi-morbidity and low life expectancy. It is precisely these patients who have the highest risk of inappropriate prescription, adverse effects and drug interactions and paradoxically where there is the least evidence of the risks and benefits of different treatments and where clinicians have the most difficulties making decisions about prescription and non-prescription. STOPP-Frail criteria may represent a tool to effectively help with this task.

The most frequent pharmacological groups identified as potentially inappropriate medication in our study were: proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) at full therapeutic dose, neuroleptics and antiplatelet drugs in primary cardiovascular prevention. In comparison to the study by Lavan et al.,14 conducted in institutionalised patients, we found similarities such as the fact that PPIs are the most frequent PIP pharmacological group (31.4%), followed by lipid-lowering drugs (29.6%), nutritional supplements (25.5%) and neuroleptics (24.5%). Very similar results are found in other studies carried out in Dutch patients in residential care: PPIs (34.8%), neuroleptics (27.9%), statins (16.3%).18 Likewise, a descriptive study conducted in Ireland by Curtin et al.16 found that proton pump inhibitors, antipsychotics and calcium supplements represented around 59% of the inappropriate medications detected. Higher rates of neuroleptics prescription (38.28%) were detected in a Spanish cohort of institutionalised older patients with severe frailty.19 Furthermore, we found a study performed in an Irish institutionalised population, where lower rates of neuroleptics prescriptions were reported (14.4%)16 compared to the rest of the studies consulted, including our own study. These different rates of medications observed can be explained by the different baseline characteristics of patients in different studies and different prescription trends in each country.

Regarding the analysis of factors associated with potentially inappropriate prescribing in our study, we found a statistically significant difference between the number of drugs prescribed and the presence of polypharmacy. Moreover, we found similar results in Lavan et al.’s study which describes a significant association between the number of drugs prescribed and the risk of receiving PIP according to STOPP-Frail criteria. The risk of receiving PIP increased by 58% for each additional medication prescribed.14 Similarly, the study by Kucukdagli et al., states that the presence of polypharmacy was independently associated with the possibility of receiving potentially inappropriate drugs, however this study uses Beers 2012 criteria, which are not specially designed for populations with severe cognitive or functional impairment and poor life expectancy, as is the case with our sample. A statistically significant relationship with other geriatric conditions such as malnutrition, depression, falls in the previous year and dementia, was also established.20

In terms of the costs, our study found a high impact on health expenditure associated with the prescription of potentially inappropriate drugs, similar to that reflected in studies such as Unutmaz et al., conducted in a Turkish population admitted to an acute geriatric unit21 and that of Harrison et al., which includes an Australian institutionalised population.22 It should be noted that the highest economic cost is attributed to therapeutic groups which are not frequently used (nutritional supplements and memantine) and it would be interesting to emphasise detection of these drugs, carefully assessing their indication in these stages of advanced disease.

In summary, most published studies evaluating PIP in patients with advanced dementia have been carried out in care homes and according to STOPP-Frail criteria find prevalence figures for PIP of 60–90%, with PPIs and neuroleptics generally being the most frequently involved pharmacological groups.

Explicit criteria are valuable tools for reviewing medication in order to improve prescription in patients with advanced dementia, but these criteria on their own are not sufficient to improve quality of care for older patients. Frequently prescribed medications (insulin, diuretics, anticoagulants, etc.) are associated with adverse events and are not always included in explicit criteria. In addition, these criteria exclude acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (ACIs) used in 17% of the population with severe dementia in their final year of life. Finally, reducing PIP is only one part of an overall approach to improve quality of care for dementia patients in their final phase of life.

The main limitation of our study is that it is a single-centre study in Madrid. Since this is a retrospective study, one might argue that patients without an advanced dementia diagnosis or whose diagnosis was not reflected in the GHC admission report were not included. Furthermore, therapeutic compliance was not evaluated this being the reason why we did not include A1 and A2 STOPP-Frail criteria. After our study had finished, a recent new version of STOPP-Frail criteria has been published but we do not believe it affects our results overall.23 We did not include patients with active oncological disease to avoid bias since these patients require an increased need for medical treatment.

On the other hand, the study's main strength is that it focuses on a particularly vulnerable population group for which there is little available evidence, i.e. very elderly community-dwelling patients with advanced dementia and palliative needs, with high comorbidity and a high level of functional and psychological dependence. Elements of comprehensive geriatric assessment (VIG) such as Frail-VIG Index were included to determine prognosis, and explicit criteria (STOPP-Frail) specifically designed for these patients were also used.

ConclusionsPIP is frequent in severely demented community-dwelling patients with poor prognosis and we have proved a positive correlation with the number of drugs prescribed and polypharmacy as well as high economic impact. The main drugs identified are proton pump inhibitors, antiplatelet drugs and neuroleptics.

Therefore, implementing strategies in this population is necessary in order to improve prescription, as well as prospective studies to determine the impact on health outcomes, such as hospitalisation and quality of life, when applying these criteria.

Ethical approvalThe study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Alfonso X el Sabio University (Madrid, Spain).

Conflict of interestOn behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Informed consentParticipants provided written informed consent for the study.

We would like to thank Dr. Alberto Socorro García and Dr. Juan José Baztán Cortés for their support.