Quality of life (QoL) is a key outcome for elderly cancer patients. The EORTC has developed QLQ-ELD14, a questionnaire that assesses important age-specific issues for older patients with cancer. This study aims to validate QLQ-ELD14 for use with elderly Spanish breast cancer patients.

Materials and methodsA consecutive sample of breast cancer patients with localized disease (age ≥65) who had received surgery ≥5 years earlier, were disease-free, and may have received adjuvant treatments was included. Patients completed the QLQ-ELD14, QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 questionnaires. A subsample of patients completed QLQ-ELD14 six months later. Psychometric evaluation of the structure, reliability and validity of QLQ-ELD14 was conducted.

Results87 patients completed the first assessment and 30 the second. Multitrait scaling analysis showed that all items except two met the standards for convergent and divergent validity. Cronbach's coefficient met the 0.7 alpha criterion on all scales except worries about others.

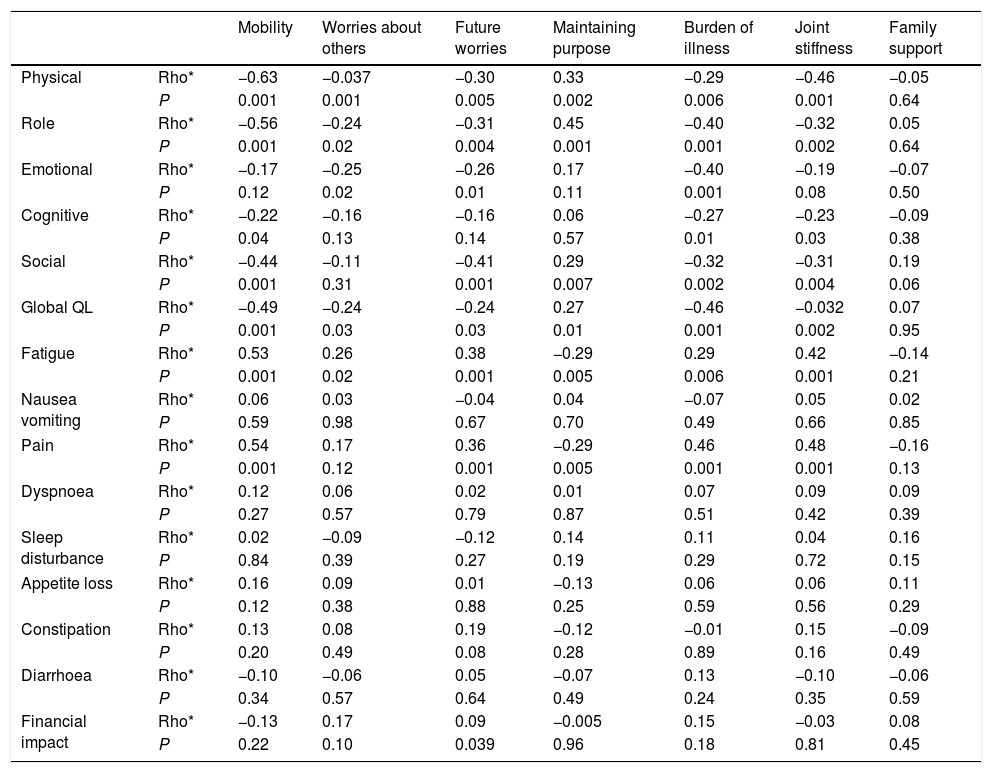

Areas of QLQ-ELD14 and QLQ-C30 whose contents are conceptually related correlated substantially (Spearman's Rho >0.40). Conversely, areas of QLQ-ELD14 that had less in common with those of QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 had low correlations (Spearman's Rho <0.1).

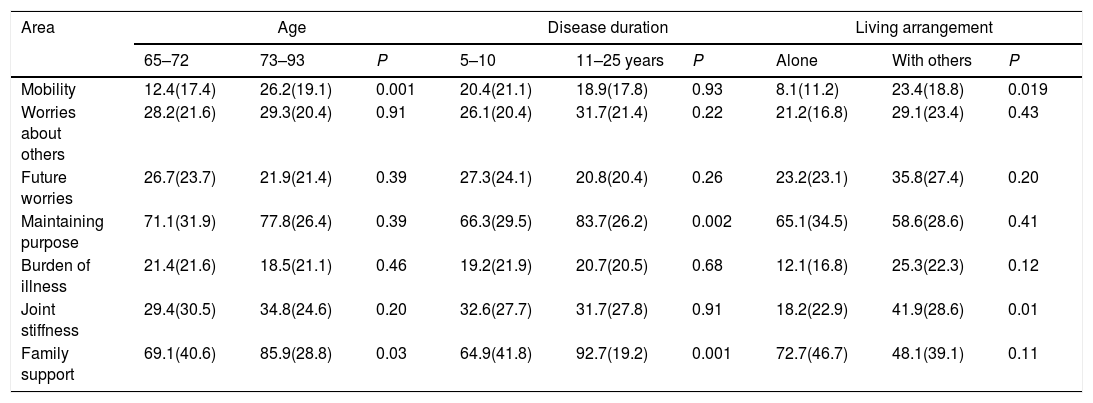

Differences in QLQ-ELD14 were found in groups based on age, disease duration, living arrangement, presence of limiting comorbidity, and level of performance status. Patients had a higher level of worries at the second assessment.

ConclusionsQLQ-ELD14 is a reliable and valid instrument when applied to a sample of Spanish patients. Our results are in line with those of other validation studies.

La Calidad de Vida (CV) es un resultado importante en los pacientes mayores con cáncer. La EORTC ha desarrollado el QLQ-ELD14, cuestionario que evalúa aspectos importantes específicos en mayores con cáncer. Se pretende validar el QLQ-ELD14 para su aplicación en pacientes mayores con cáncer de mama.

Materiales y métodosUna muestra consecutiva de pacientes con cáncer de mama y enfermedad localizada (edad≥65) que habían recibido cirugía≥5 años antes, y podían haber recibido tratamientos adyuvantes fue incluida. Las pacientes han contestado los cuestionarios QLQ-ELD14, QLQ-C30 y QLQ-BR23. Una submuestra el cuestionario QLQ-ELD14 6 meses después. Se ha evaluado la estructura, la fiabilidad y la validez del cuestionario QLQ-ELD14.

ResultadosOchenta y siete pacientes han contestado la primera medición y 30 la segunda. El análisis multirrasgo-multimétodo ha mostrado que todos los ítems excepto 2 presentaban valores adecuados de validez convergente y divergente.

Todas las escalas, excepto preocupación por los otros, satisfacían el criterio de Alfa de Cronbach 0.7.

Áreas del QLQ-ELD14 y QLQ-C30 cuyo contenido estaba más relacionado presentaban correlaciones altas (Rho de Spearman>0,40). Áreas del QLQ-ELD14 menos relacionadas con el QLQ-C30 y QLQ-BR23 presentaban correlaciones más bajas (Rho de Spearman<0,1).

Se han encontrado diferencias significativas en el QLQ-ELD14 entre grupos basados en edad, duración de la enfermedad, convivencia, comorbilidad y estado funcional. Las pacientes presentaban un nivel mayor de preocupaciones en la segunda medición.

ConclusionesEl cuestionario QLQ-ELD14 es un instrumento fiable y válido en su aplicación a pacientes españoles. Nuestros resultados van en la línea de otros estudios de validación.

The incidence of cancer in the elderly population is increasing because of increased life expectancy.1 Since the risk of breast cancer increases significantly with age, the prevalence of breast cancer is highest in elderly patients.2 Improving Quality of Life (QoL) is one of the main aims of treatment for elderly breast cancer patients.3

Today there is much interest in studying the QoL of elderly cancer patients.1,4,5 These patients are underrepresented in cancer clinical trials6 and may be vulnerable to treatment toxicities.7 Information on how disease and treatments affect the QoL of elderly patients’ can be very helpful. Assessing the QoL of such patients is also important in routine clinical practice.8

QoL in elderly patients is a broad construct that includes more dimensions than simply mental and physical health in general.9 Moreover, as ageing is highly individualized, QoL in elderly cancer patients is heterogeneous.10 These patients may have a different QoL profile than younger patients. Differences are found in the level of limitations and what may be considered the most relevant QoL areas. However, the specific needs of elderly patients are often ignored in the development, validation and use of HRQOL instruments.11

Instruments tailored to assess QoL in elderly cancer patients have only recently been introduced.12 More QoL questionnaires specific to these patients are needed.6

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) has a working group on QoL. One of this group's main tasks is to develop questionnaires to assess QoL in clinical trials and clinical practice. The group uses a modular approach that includes a core questionnaire (QLQ-C30) designed to evaluate QL across a wide spectrum of patient populations and treatments plus a range of supplementary modules designed to assess specific issues according to the type of treatment or disease site, or dimensions such as fatigue.13,14 These modules include the QLQ-BR23 for breast cancer15 and the QLQ-CR29 for colorectal tumours.16

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is one of the most widely used questionnaires for assessing QoL in cancer patients.13 However, it does not meet all the needs of QoL assessment in patients aged ≥70 years.17 Moreover, substantial age-related differences have been found in responses to the EORTC QLQ-C30.18,19

The EORTC QLQ-ELD14 contains important age-specific issues for elderly cancer patients. The module, which was developed to supplement the QLQ-C30,12 is different from other EORTC tumour-site-specific modules (such as the breast or colorectal modules) because it is applicable to patients with all kind of cancers. Compared to other EORTC tumour site modules, it has a stronger than normal focus on the psycho-social side of QoL problems. Also, to reduce the patients’ burden it has a low small number of items (14).20

This tool was developed12 in a multicultural, multidisciplinary setting (which included Spain). The questionnaire, validated with patients from 10 countries, demonstrated good psychometric properties and a high compliance rate.20

The aims of the present study are to determine the psychometric properties of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 questionnaire when applied to a sample of elderly Spanish breast cancer patients with localized disease and to compare the results of these analyses with those of the previous validation study conducted by the EORTC QoL study group.20

MethodsParticipantsA consecutive sample of breast cancer patients treated at the Oncology Departments of the Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra were invited to participate in this study between February 2017 and June 2018. Inclusion criteria were primary breast cancer, stage I–IIIA, and age 65 or above when the QoL questionnaires were completed. Patients had been subjected to surgery ≥5 years earlier and were disease-free and without relapse or second malignancy during the follow-up period. Patients underwent a mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery with axillary evaluation per clinical discretion (SLNB, ALND, no surgery). Patients may have received adjuvant treatments (radiotherapy, chemotherapy and/or endocrine therapy). Criteria for exclusion were a cognitive state that precluded treatment or life expectancy of less than three months.

MeasuresAll patients completed the EORTC QLQ-C30 version 3.013 and the QLQ-BR23,15 which had been validated for use in Spain,21,22 and the QLQ-ELD14.20 In line with the EORTC QoL Study Group translation procedure, these instruments had been translated into Spanish using a forward–backward translation process.23

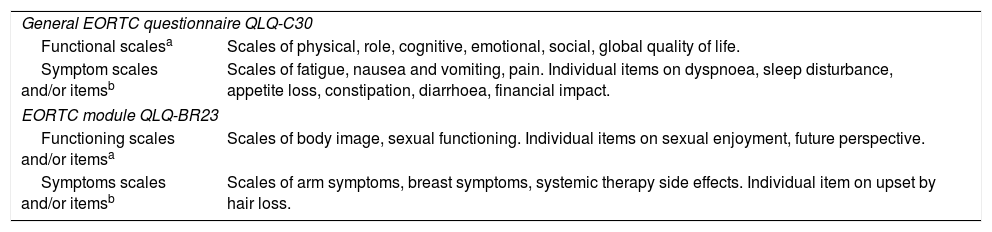

QLQ-C30 comprises 30 items to assess areas common to different tumour sites and treatments and contains five functioning scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social), eight symptoms scales and/or items (fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, sleep disturbance, appetite loss, constipation and diarrhoea), a financial impact item, and a global scale. QLQ-BR23 assesses areas associated with breast cancer and its treatments. It contains 4 functioning scales and/or items (body image, sexual functioning, arm symptoms, future perspective) and 4 symptoms scales and/or items (arm and breast symptoms, systemic therapy side effects, and upset by hair loss). Scores in all areas of these two questionnaires range from 0 to 100. Higher scores represent higher functional levels or degrees of symptoms (see Table 1).

Content of the general questionnaire and the breast cancer module.

| General EORTC questionnaire QLQ-C30 | |

| Functional scalesa | Scales of physical, role, cognitive, emotional, social, global quality of life. |

| Symptom scales and/or itemsb | Scales of fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain. Individual items on dyspnoea, sleep disturbance, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea, financial impact. |

| EORTC module QLQ-BR23 | |

| Functioning scales and/or itemsa | Scales of body image, sexual functioning. Individual items on sexual enjoyment, future perspective. |

| Symptoms scales and/or itemsb | Scales of arm symptoms, breast symptoms, systemic therapy side effects. Individual item on upset by hair loss. |

The EORTC QLQ-ELD14 is a 14-item cancer-specific module comprising five multi-item scales that assess mobility, worries about others, future worries, maintaining purpose, and burden of illness. It also includes two single items on joint stiffness and family support. Scores in all areas also range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating worse QoL in the case of mobility, joint stiffness, worries about others, future worries, and burden of illness, and better QoL in family support (feel able to talk to the family about the illness) and maintaining purpose.20

Performance status (level of physical functioning) was assessed by the physician (Karnofsky scale),24 as was level of comorbidity (Charlson Comorbidity Index).25

Data collection proceduresPatients who provided informed consent completed the QoL questionnaires in a follow-up visit (at least five years after surgery). A subgroup of patients who received endocrine treatment (tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitor) for five years after breast surgery were assessed after endocrine treatment had just ended and six months later, when they also completed the QLQ-ELD14.

Sociodemographic data (age, living arrangement) and clinical data (disease duration, breast and axillary surgery, adjuvant treatment, i.e. chemotherapy, radiotherapy and endocrine therapy) were taken from clinical records.

This study, approved by the Regional Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research, followed the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysesClinical and demographic characteristics and QoL scores were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Multitrait scaling analysis26 was performed in the first assessment to examine whether the individual items of EORTC QLQ-ELD14 could be aggregated into the hypothesized multi-item sub-scales. Evidence of item convergent validity was defined as an item-own-scale correlation of P≥0.40 (corrected for overlap). Item discriminant validity was supported, and a scaling success was counted when the correlation between an item and its hypothesized sub-scale (corrected for overlap) was higher than its correlation with the other sub-scale.

The Internal consistency reliability of the scales was measured (Cronbach's alpha coefficient ≥0.70 criteria) at the first assessment.27

Questionnaire validity was studied using three approaches. For convergent and divergent validity, correlations between the areas of QLQ-ELD14 with those of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 were calculated at the first assessment (Spearman's correlation coefficients, with two-tail analysis, also in the multitrait analyses). Scales and items whose contents are conceptually related were expected to correlate substantially with each other (Spearman's Rho>0.40=large correlation), e.g. mobility with physical and role functioning, and joint stiffness with physical functioning. Conversely, areas with less in common were expected to correlate less (Spearman's Rho<0.15=small correlation), e.g. worries about others with systemic therapy side effects, and family support with body image.

Known-group comparisons was conducted at the first assessment (Mann–Whitney U tests, P<0.05) to study the extent to which the QLQ-ELD14 differentiates between groups of patients who differ in age (65–72 or 73–93), disease duration (5–10 or 11–25 years), living arrangement (living alone or with others), the presence of limiting comorbidity (yes or no), and level of performance status (60–80 or 90–100). Living arrangement was also compared in the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 questionnaires.

Better QoL was expected among younger patients10 and patients with a longer disease duration,28 patients living with company,29 those with no limiting comorbidity20 and those with higher performance status.13

Responsiveness to changes was studied in patients who completed both QLQ-ELD14 assessments. Scores in the two measurements were compared (Wilcoxon test). Better QoL was expected at the second assessment.30

ResultsWe evaluated 87 patients out of 92 candidates. Reasons for not completing the questionnaires were administrative failure (3 cases) and patient refusal (2 cases). 30 patients completed the QLQ-ELD14 twice. All questionnaires had >90% items answered.

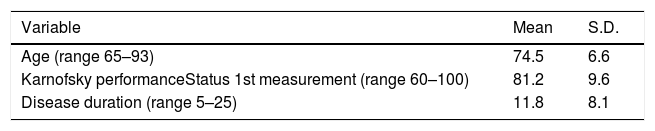

Mean age was 74.5 years and 31% of the patients lived alone. Most patients received breast-conserving surgery, sentinel node biopsy, radiotherapy and aromatase inhibitor. Fifty-eight (66.7%) patients had pretreatment limiting comorbidity: arthrosis (31; 35.6%), arterial hypertension (22; 25.3%), heart failure (7; 8.1%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (5; 5.7%), and hip fracture (3; 3.4%). Mean values for performance status were high. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Characteristics of the sample.

| Variable | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|

| Age (range 65–93) | 74.5 | 6.6 |

| Karnofsky performanceStatus 1st measurement (range 60–100) | 81.2 | 9.6 |

| Disease duration (range 5–25) | 11.8 | 8.1 |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Cohabitance | ||

| Alone | 27 | 31 |

| Couple | 39 | 44.8 |

| Children >18 years | 11 | 12.6 |

| Other persons (siblings, residence and others) | 10 | 11.6 |

| Breast surgery | ||

| Mastectomy | 21 | 24.2 |

| Conservative | 66 | 75.8 |

| Axillary surgery | ||

| ALND | 31 | 35.6 |

| SLNB | 42 | 48.3 |

| No surgery | 14 | 16.1 |

| Chemotherapy | 47 | 54.1 |

| Radiotherapy | 72 | 82.7 |

| Endocrine therapy | ||

| Tamoxifen | 14 | 16.1 |

| AI | 50 | 57.5 |

| No | 23 | 26.4 |

| Limiting comorbidity | ||

| Yes | 58 | 66.6 |

Types of axillary surgery: SLNB, sentinel node biopsy; ALND, axillary node dissection; AI, aromatase inhibitor.

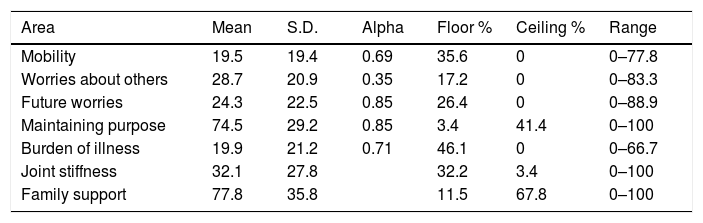

Questionnaire descriptive statistics. Table 3 shows that the mean scores were high in most QoL areas. Moderate limitations (>30) occurred in joint stiffness, while light limitations (20–29) occurred in worries about others, future worries, maintaining purpose, and family support. There was a moderate percentage of respondents at floor in the burden of illness area and at ceiling in maintaining purpose. There was a ceiling effect in family support. The range of scores was broad in all QLQ-ELD14 questionnaire areas (Table 3).

Scores in the 1st measurement.

| Area | Mean | S.D. | Alpha | Floor % | Ceiling % | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility | 19.5 | 19.4 | 0.69 | 35.6 | 0 | 0–77.8 |

| Worries about others | 28.7 | 20.9 | 0.35 | 17.2 | 0 | 0–83.3 |

| Future worries | 24.3 | 22.5 | 0.85 | 26.4 | 0 | 0–88.9 |

| Maintaining purpose | 74.5 | 29.2 | 0.85 | 3.4 | 41.4 | 0–100 |

| Burden of illness | 19.9 | 21.2 | 0.71 | 46.1 | 0 | 0–66.7 |

| Joint stiffness | 32.1 | 27.8 | 32.2 | 3.4 | 0–100 | |

| Family support | 77.8 | 35.8 | 11.5 | 67.8 | 0–100 |

Scores (mean and S.D.) in the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 questionnaire in the first measurement.

Higher scores indicate: a worse QoL in mobility, joint stiffness, worries about others, future worries, and burden of illness; and a better QoL in family support and maintaining purpose. Alpha: Cronbach's Alpha.

Floor %: percentage of respondents at the lowest scale rating; Ceiling %: percentage of respondents at the highest scale rating.

Range: range of the scores in each dimension.

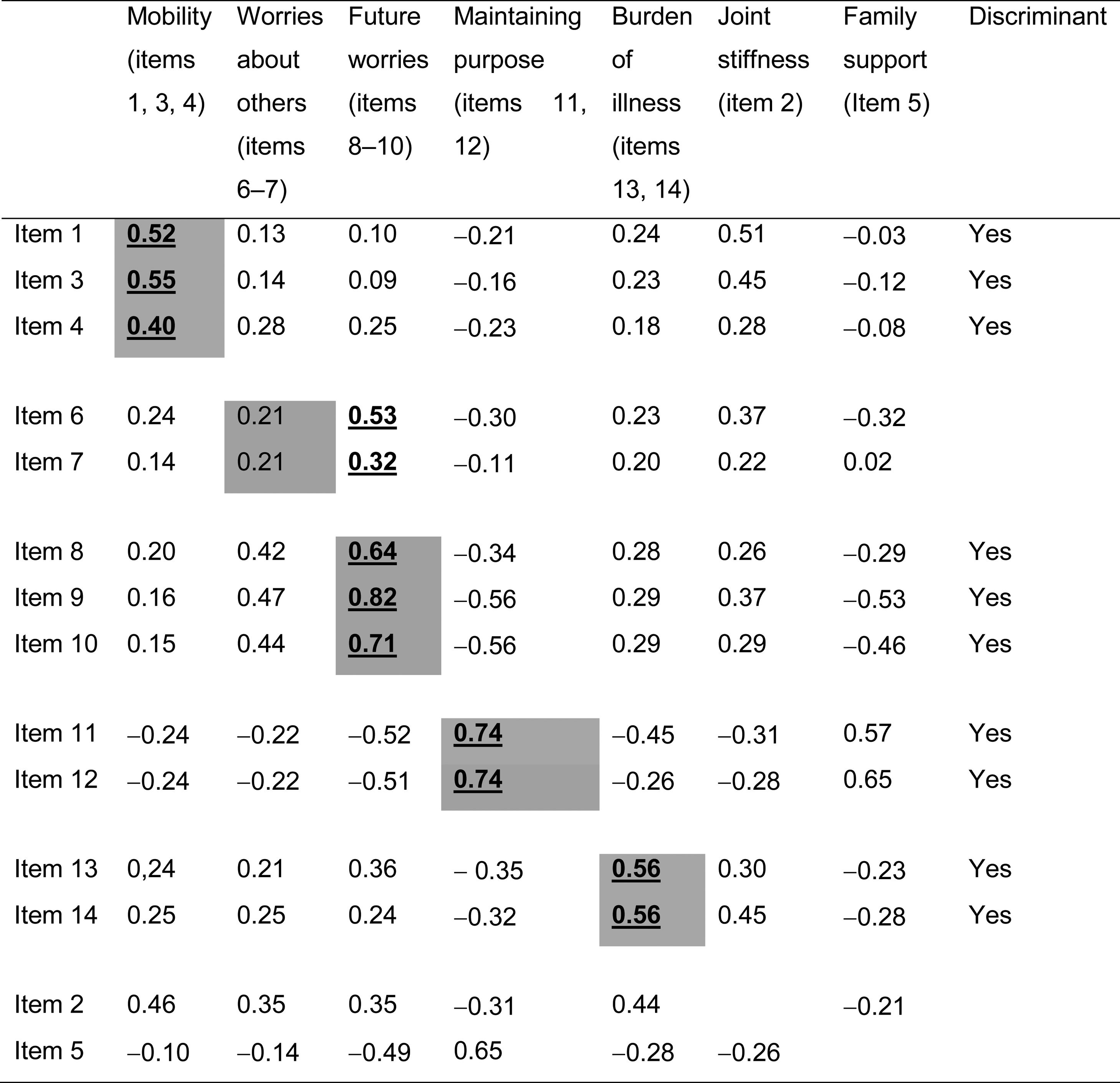

All items exceeded the 0.4 criterion for convergent validity, except items 6 and 7 (which make up the worries about others scale). Discriminant validity was successful in all analyses except for items 6 and 7, which showed the highest correlation (0.53 and 0.32) with the future worries scale. The joint stiffness item showed moderate correlations with items 1 and 3 on the mobility scale (0.51 and 0.45, respectively) (Table 4).

Multitrait analyses.

Cells in grey: correlations between each item and its own scale (corrected for overlap).

Cells in white: correlations between each item and the other scales.

Numbers underlined and in black: highest correlations between an item and the different scales.

Discriminant: item discriminant validity.

With regard to internal consistency reliability, all scales except worries about others fitted the 0.70 criterion or were very close to it (mobility scale 0.69) (Table 3).

With regard to convergent and divergent validity, the highest correlations between QLQ-ELD14 and EORTC QLQ-C30 were found: between QLQ-ELD14 mobility and EORTC QLQ-C30 physical functioning (−0.63, the highest correlation in the study), role functioning, fatigue and pain (−0.56 to 0.53); between QLQ-ELD14 burden of illness and QLQ-C30 pain and global (0.46 in both cases); and between QLQ-ELD14 joint stiffness and QLQ-C30 physical functioning and pain (−0.46 and 0.48, respectively) (see Table 5). No correlation between QLQ-ELD14 and QLQ-BR23 was ≥0.40: the correlation between QLQ-ELD14 future worries and QLQ-BR23 future perspective was 0.33 (data non-shown).

Convergent and divergent validity.

| Mobility | Worries about others | Future worries | Maintaining purpose | Burden of illness | Joint stiffness | Family support | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Rho* | −0.63 | −0.037 | −0.30 | 0.33 | −0.29 | −0.46 | −0.05 |

| P | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.64 | |

| Role | Rho* | −0.56 | −0.24 | −0.31 | 0.45 | −0.40 | −0.32 | 0.05 |

| P | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.64 | |

| Emotional | Rho* | −0.17 | −0.25 | −0.26 | 0.17 | −0.40 | −0.19 | −0.07 |

| P | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.08 | 0.50 | |

| Cognitive | Rho* | −0.22 | −0.16 | −0.16 | 0.06 | −0.27 | −0.23 | −0.09 |

| P | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.38 | |

| Social | Rho* | −0.44 | −0.11 | −0.41 | 0.29 | −0.32 | −0.31 | 0.19 |

| P | 0.001 | 0.31 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.06 | |

| Global QL | Rho* | −0.49 | −0.24 | −0.24 | 0.27 | −0.46 | −0.032 | 0.07 |

| P | 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.95 | |

| Fatigue | Rho* | 0.53 | 0.26 | 0.38 | −0.29 | 0.29 | 0.42 | −0.14 |

| P | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.21 | |

| Nausea vomiting | Rho* | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| P | 0.59 | 0.98 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.66 | 0.85 | |

| Pain | Rho* | 0.54 | 0.17 | 0.36 | −0.29 | 0.46 | 0.48 | −0.16 |

| P | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.13 | |

| Dyspnoea | Rho* | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| P | 0.27 | 0.57 | 0.79 | 0.87 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.39 | |

| Sleep disturbance | Rho* | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.12 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.16 |

| P | 0.84 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.72 | 0.15 | |

| Appetite loss | Rho* | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| P | 0.12 | 0.38 | 0.88 | 0.25 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.29 | |

| Constipation | Rho* | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.19 | −0.12 | −0.01 | 0.15 | −0.09 |

| P | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.89 | 0.16 | 0.49 | |

| Diarrhoea | Rho* | −0.10 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.13 | −0.10 | −0.06 |

| P | 0.34 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.59 | |

| Financial impact | Rho* | −0.13 | 0.17 | 0.09 | −0.005 | 0.15 | −0.03 | 0.08 |

| P | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.039 | 0.96 | 0.18 | 0.81 | 0.45 |

Correlations between the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-ELD14.

Conversely, the lowest correlations between QLQ-ELD14 and EORTC QLQ-C30 were found: between QLQ-ELD14 future worries and QLQ-C30 nausea and vomiting, appetite loss and dyspnoea (−0.04, 0.01 and 0.02, respectively); and between QLQ-ELD14 maintaining purpose and QLQ-C30 dyspnoea and financial impact (0.01 and 0.005, respectively) (Table 5). The lowest correlation between QLQ-ELD14 and EORTC QLQ-BR23 were found: between QLQ-ELD14 worries about others and QLQ-BR23 systemic therapy side effects and sexual functioning (0.008 and 0.01, respectively); and between QLQ-ELD14 family support and QLQ-BR23 body image, systemic therapy side effects and future worries (0.004, −0.005 and 0.003, respectively) (data non-shown).

With regard to known group comparison, significant relationships were observed in the different groups compared. Elderly patients showed higher mobility scores (more limitations) and higher family support (felt more able to talk to the family about their illness). Patients with longer disease duration showed higher family support and maintained more purpose in life. Patients who lived alone showed lower mobility scores and lower joint stiffness (lower limitations in both cases). These patients also had better physical functioning in the QLQ-C30 (mean 91.1–80.0, P=0.05) with no differences in the QLQ-C30 emotional or social functioning scales or in the other QLQ-ELD14 areas. Patients with no limiting comorbidity had lower mobility scores (lower limitations). Patients with higher performance status had lower mobility scores and less joint stiffness (lower limitations in both cases) (Table 6).

Known group comparisons.

| Area | Age | Disease duration | Living arrangement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65–72 | 73–93 | P | 5–10 | 11–25 years | P | Alone | With others | P | |

| Mobility | 12.4(17.4) | 26.2(19.1) | 0.001 | 20.4(21.1) | 18.9(17.8) | 0.93 | 8.1(11.2) | 23.4(18.8) | 0.019 |

| Worries about others | 28.2(21.6) | 29.3(20.4) | 0.91 | 26.1(20.4) | 31.7(21.4) | 0.22 | 21.2(16.8) | 29.1(23.4) | 0.43 |

| Future worries | 26.7(23.7) | 21.9(21.4) | 0.39 | 27.3(24.1) | 20.8(20.4) | 0.26 | 23.2(23.1) | 35.8(27.4) | 0.20 |

| Maintaining purpose | 71.1(31.9) | 77.8(26.4) | 0.39 | 66.3(29.5) | 83.7(26.2) | 0.002 | 65.1(34.5) | 58.6(28.6) | 0.41 |

| Burden of illness | 21.4(21.6) | 18.5(21.1) | 0.46 | 19.2(21.9) | 20.7(20.5) | 0.68 | 12.1(16.8) | 25.3(22.3) | 0.12 |

| Joint stiffness | 29.4(30.5) | 34.8(24.6) | 0.20 | 32.6(27.7) | 31.7(27.8) | 0.91 | 18.2(22.9) | 41.9(28.6) | 0.01 |

| Family support | 69.1(40.6) | 85.9(28.8) | 0.03 | 64.9(41.8) | 92.7(19.2) | 0.001 | 72.7(46.7) | 48.1(39.1) | 0.11 |

| Area | Presence of limiting comorbidity | Level of performance status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P | 60–80 | 90–100 | P | |

| Mobility | 27.1(21.2) | 14.0(16.2) | 0.003 | 25.0(19.6) | 8.1(12.9) | 0.001 |

| Worries about others | 30.2(22.5) | 27.7(19.8) | 0.83 | 31.3(20.8) | 23.6(21.1) | 0.12 |

| Future worries | 24.9(24.3) | 23.8(21.3) | 0.94 | 24.6(22.7) | 24.1(22.8) | 0.87 |

| Maintaining purpose | 69.4(28.7) | 78.3(29.2) | 0.12 | 75.6(28.1) | 74.7(31.3) | 0.81 |

| Burden of illness | 21.2(22.8) | 19.0(20.2) | 0.75 | 21.4(21.9) | 16.7(19.4) | 0.37 |

| Joint stiffness | 36.1(25.3) | 29.3(29.1) | 0.19 | 35.1(26.5) | 22.9(25.4) | 0.03 |

| Family support | 80.2(34.6) | 76.0(36.9) | 0.46 | 83.3(27.5) | 75.5(43.1) | 0.12 |

Results of the known groups comparisons. Subgroups were compared based on: age, disease duration, living arrangement, presence of limiting comorbidity, level of performance status for 1st assessment.

With regard to responsiveness to changes, there was a significant difference between the two assessments in future worries, i.e. patients had a higher level of worries at the second assessment than they did at the first (P 0.01; means 38.8 and 44.9, respectively).

DiscussionThis paper presents the results of a validation study for the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 for Spain. Levels of compliance and missing data percentages indicate that the instrument was well accepted. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were representative of patients treated at the Oncology Departments.

The questionnaire shows high QoL scores that are adequate for patients at initial disease stages and in follow-up. These high QoL scores indicate that the patients have adapted well to their disease and treatment. Scores in most QLQ-ELD14 areas showed lower QoL limitations than those in a sample of very elderly patients ≥80 years (older than those in our study) that comprised patients at initial and advanced disease stages who had started treatment. These differences are normal since we expect older patients to have more limitations due to their longer period of ageing.10

The low percentage of respondents at floor and at ceiling in most QLQ-ELD14 areas, and the range of scores in all questionnaire areas, indicate that the questionnaire has a high sensitivity. The moderate percentage of respondents at floor in the burden of illness area and at ceiling in maintaining purpose may be related to the good clinical characteristics of the sample. The high scores and ceiling effect in the family support scale may be specific to our cultural area, where family plays a key role.

Except for the scale on worries about others, multitrait scaling analyses confirmed the multi-item structure of most questionnaire scales (as in the international validation study20 and the validation study for Poland6). Moderate correlations between joint stiffness and the mobility scale were also found in the international validation study20 and the validation study for Korea.31 The authors of the QLQ-ELD14 decided to keep joint stiffness as a separate item because they considered it was conceptually different from the items of the mobility scale. The relation between these two areas may be because a high level of joint stiffness may limit mobility.31

Internal consistency reliability for the various scales was highly satisfactory, as it was in the international validation study20 and the validation studies for Poland6 and Korea31 (except in the worries about others scale as in the validation study for Korea32 where alpha was 0.65). As we have shown in the multitrait analyses, in our study the items on the worries about others scale did not show good convergent validity. As in the validation study for Korea31 these items showed the highest correlations with the future worries scale. The worries about others scale may be considered adequate since it evaluates worries, though the content of its items (6 and 7) may be less related in our culture. The maintaining the purpose scale had a higher Cronbach's Alpha than in the international validation study20 (where it was 0.68).

Convergent and divergent validity with the QLQ-C30 were satisfactory. Areas with more related meanings showed higher correlations (e.g. between mobility and physical and role functioning and fatigue). Similarly, areas with less-related contents showed lower correlations (e.g. between QLQ-ELD14 future worries and QLQ-C30 nausea and vomiting, appetite loss and dyspnoea). As in the international validation study20 and the validation studies for Poland6 and Korea,32 mobility plays a central role in the QoL of our elderly patients. The correlation between the future worries scale and the QLQ-BR23 future perspective item was not very high (0.33), which indicates that these scales may not assess the same areas. For example, the QLQ-BR23 item measures patient worries about future health, whereas the QLQ-ELD14 scale also includes items on uncertainty about the future and worries about what may happen at the end of life.

Known group validity analyses were generally supported by the data. Differences in the mobility scale in age-related groups were also found in a study with very elderly cancer patients.10 For example, lower physical functioning was also found in older patients that were included in a sample of elderly cancer patients.32 More support from family in older patients and those with a longer disease duration may be related to better adaptation to the situation, since the patients feel more able to talk to their family about their illness. Also, maintaining more purpose in life in patients with a longer disease duration may be related to better patient adaptation to their situation over time. In this context, Minniti et al.28 found better QoL in patients with a longer disease duration.

Patients who lived alone showed better mobility, less joint stiffness, and better physical functioning than patients who lived with others. Moreover, no differences were found in social or emotional functioning or indeed in any other QLQ-ELD14 area. These results seem to indicate that the patients in our study who lived alone retained an adequate level of support for their social, family and emotional needs and had better autonomy. This may be because these patients had the disease in initial stages, had finished treatment at least five years previously, and had a high performance status. One study found that QoL was lower in patients living alone with esophageal cancer, but the patients in that study had a worse clinical status than ours.33

Differences in mobility related to comorbidity were also found in the international validation study20 and the validation study for Poland6: These higher limitations in mobility may be related to limitations due to other diseases. Differences in performance status were also found both in the above studies and in the validation study for Spain for the QLQ-C30 questionnaire.21

As in our study, a worsening in future worries was also seen six months after the end of treatment in a sample of very elderly patients from Germany (who received radiotherapy).10 This may indicate an increase in patient anxiety after the treatment's anticancer effect had ended and suggests that support should be provided for elderly patients in the follow-up period. The above German10 study also observed a worsening in burden of the illness and family support. This increase in burden of illness may be because some patients in that study had more advanced disease stages than ours. Also, a decrease in family support over time (which we did not observe in our study) may indicate a cross-cultural difference since, as we mentioned earlier, the family plays a more important role in our culture. As in our study, few QoL changes were found in the international validation study,20 where patients had no clear change in their clinical status. The authors concluded that it would be good to study responsiveness to change in patients whose clinical status had clearly changed.

It has been reported that the best application of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 is to supplement the EORTC QLQ-C30 in order to fully evaluate generic issues affecting elderly people with cancer not covered by the EORTC QLQ-C30 or its disease-specific add-on.20

The strengths of the present study are that the sample included only elderly patients and that three different QoL questionnaires were administered. However, it could have benefited from a test-retest analysis and a different longitudinal design to measure QL both before and after an intervention.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 questionnaire demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties when applied to a sample of elderly Spanish breast cancer patients with localized disease. Our results are in line with those of the validation studies conducted by the EORTC QL study group and studies conducted in individual countries.

FundingThis study was supported by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and FEDER (project PI15/02114), the Fundación Caja Navarra – Fundación Obra Social “La Caixa”, and UNED Pamplona for a research assistant who collected the data.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

We thank all the professionals at the Oncology Departments of the Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra for their support in this study.