Histoplasmosis is a systemic infection caused by the dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum, naturally found in nitrogen-rich soil, whose main transmission route is the inhalation of conidia. Up to 95% of histoplasmosis cases are asymptomatic or transient, and the remaining 5% of cases have pathological manifestations in the lungs, bone marrow, liver, spleen, intestine, mucous membranes, and rarely on the skin. This mycosis has been reported from many endemic areas, mainly in immunosuppressed patients, such as HIV-positive patients, and its disseminated form is rarely reported.

Case reportHistoplama capsulatum was isolated and identified by means of microscopy, culture characteristics and nested PCR from the cutaneous lesions of a non-HIV patient from Vietnam. The patient improved significantly with systemic itraconazole treatment.

ConclusionsDisseminated histoplasmosis with cutaneous involvement in non-HIV patients is an extremely unusual presentation.

La histoplasmosis es una infección sistémica causada por Histoplasma capsulatum, un hongo dimorfo que se encuentra naturalmente en suelos nitrogenados, y cuya principal vía de transmisión es a través de la inhalación de conidios. Hasta el 95% de las histoplasmosis son asintomáticas o transitorias, y el 5% restante de los casos presenta manifestaciones clínicas en pulmones, médula ósea, hígado, bazo, intestino, membranas mucosas y, raramente, en piel. Esta micosis ha sido reportada en muchas áreas endémicas, mayoritariamente en pacientes inmunodeprimidos, tales como los infectados por el VIH, y su forma diseminada es infrecuente.

Caso clínicoHistoplasma capsulatum fue aislado e identificado en el examen microscópico, cultivo y PCR anidada de las lesiones cutáneas de un paciente no-VIH de Vietnam. El paciente mejoró significativamente con tratamiento sistémico con itraconazol.

ConclusionesLa histoplasmosis diseminada con manifestación cutánea en pacientes no-VIH es una presentación extremadamente inusual.

Histoplasmosis is an endemic mycosis caused by Histoplasma capsulatum (Ajellomyces capsulatus, sexual or teleomorph state), a dimorphic pathogenic fungus naturally found in soils containing bat or bird feces.3,10 This species harbors three varieties known as H. capsulatum var. capsulatum (worldwide distribution), H. capsulatum var. duboisii (African human pathogen) and H. capsulatum var. farciminosum (horse pathogen), and is composed of multiple, distinct genetic groups.9 Recently, some of these groups have been proposed as new species, whereas H. capsulatum would comprise four different cryptic species at least: H. capsulatum, Histoplasma mississippiense, Histoplasma ohiense and Histoplasma suramericanum.16

Histoplasmosis is prevalent mainly in the Central and Eastern areas of the United States, Central and South America, and Central and Western Africa.3,6,7 Autochthonous cases have been reported from Asia-Pacific regions, especially China, which reported 8.9% histoplasmin skin positive test in Hunan, 15.1% in Jiangsu, and 35% in Sichuan.1,17,19 Pan et al. classified histoplasmosis cases in China as disseminated disease in 86% of patients, with 52% of the patients without any underlying disease.15 Histoplasmosis can be diagnosed by direct microscopy, histological examination, culture, and immunological tests such ELISA.2,8,10 Culture is still considered the gold standard to diagnose histoplasmosis, but because of the slow fungal growth, culture is sometimes not preferred by physicians.4,10 Molecular techniques have been considered the most rapid diagnostic methods with high sensitivity.8,14

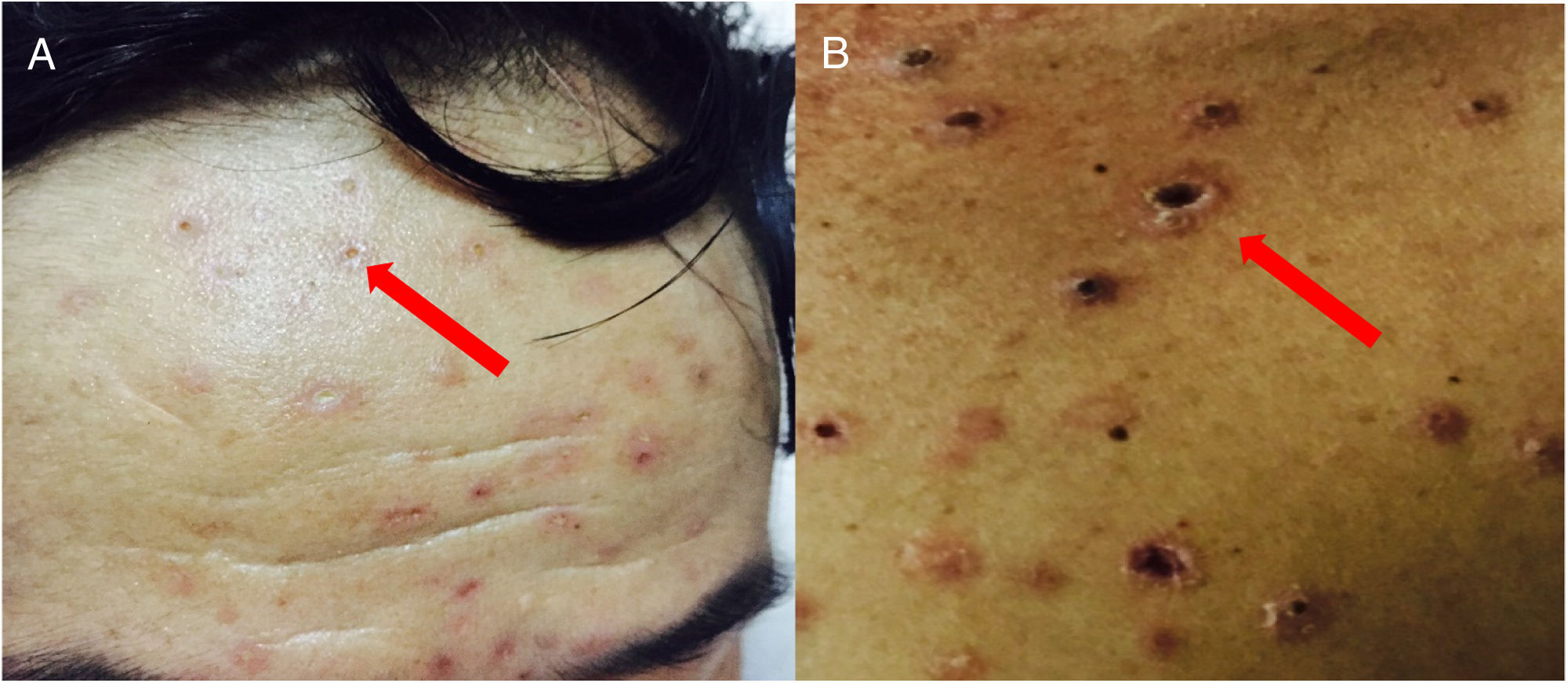

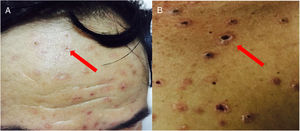

We are reporting the case of a 45 year-old male patient that lived in the Northern mountainous region of Vietnam. During the previous five months, the patient suffered fever (38–39°C/98.6–100.4°F) in the afternoon, as well as muscle aches. These symptoms were also accompanied by a weight loss of 10kg in a 2 month-period. The patient had red pustular skin lesions measuring around 2 to 3mm, which developed first on his face, and later on his limbs and other parts of the body (Fig. 1). Some lesions produced pus in the central area, whereas some others ulcerated and got necrotic, without any pain or itching. The patient had no previous history of any chronic internal disease and tested negative for HIV. Other clinical and laboratory tests were made to rule out tuberculosis, autoimmune disease, cancer, and diabetes. The patient required mechanical ventilation due to respiratory difficulties. He was suffering periodic drowsiness and had fever (39–40°C/102.2–104°F). The pustules on his skin became necrotic and they were disseminated around the whole body. Lymphocyte T CD4+ count was 408cells/μl.

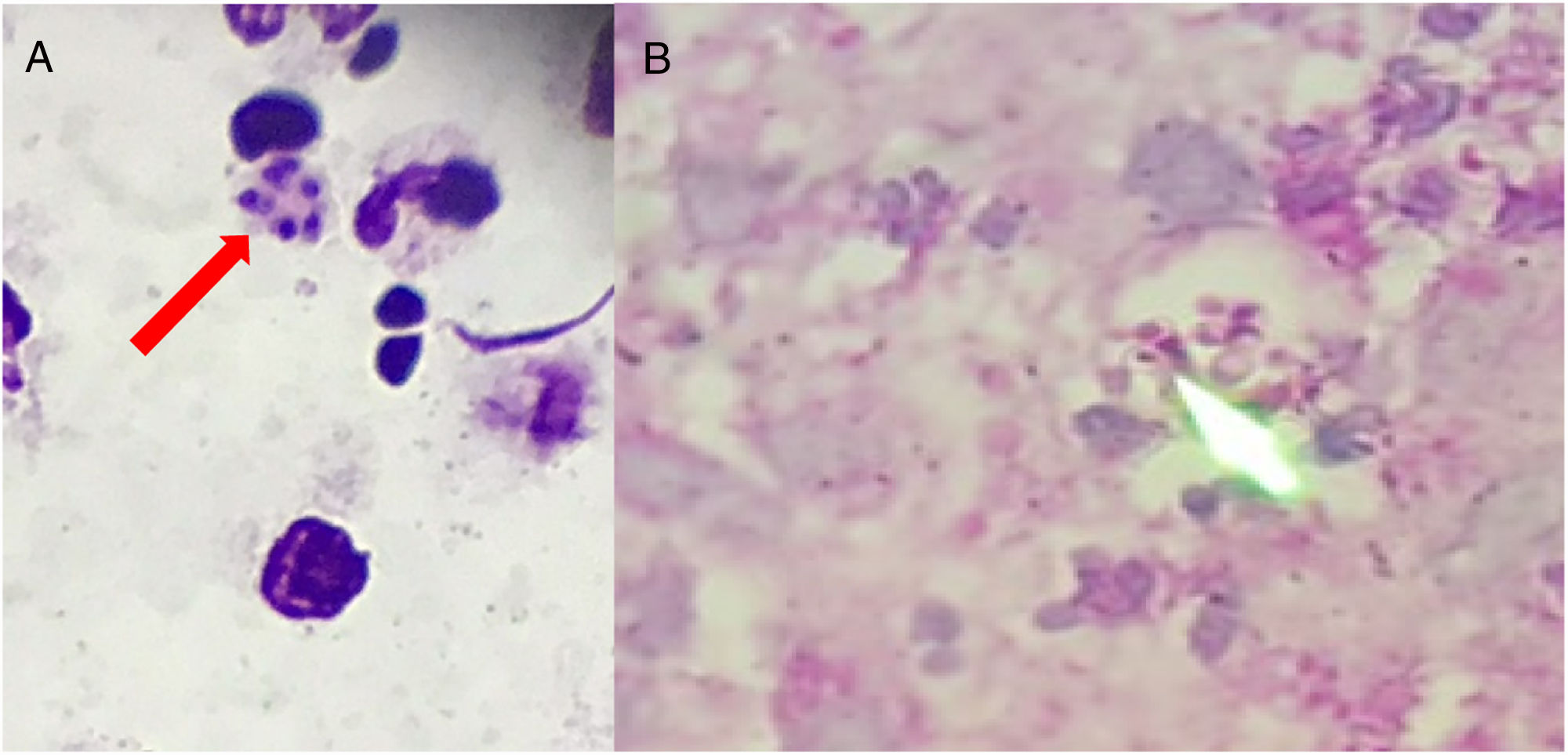

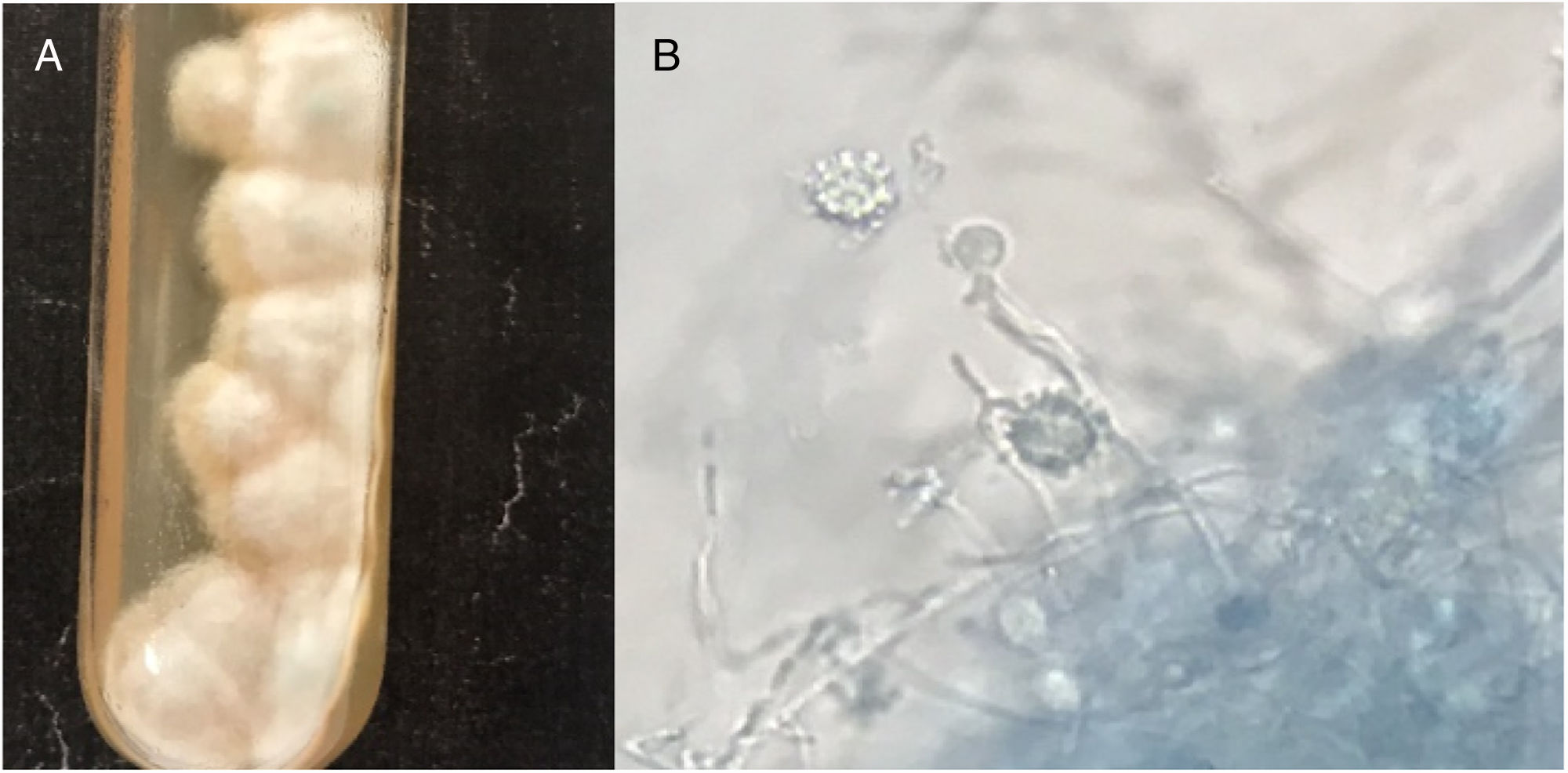

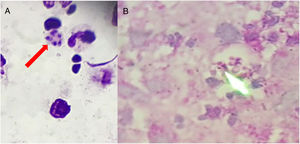

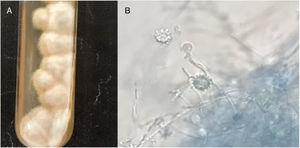

Clinical specimens (pus and fluids from ulcers; tongue and mouth scrapes) were obtained, and direct microscopy observation and culture were performed. Giemsa-stained skin fluid sample and histopathological examination of skin tissue revealed clusters of small, round, intracellular yeast-like cells of relatively equal size (4–5μm), suggestive of H. capsulatum (Fig. 2). Direct microscopic examination of tongue scrapings using 20% KOH revealed only oval yeast cells and pseudohyphae, consistent with the Candida genus. In order to confirm these results, fluid obtained from pustular skin lesions was inoculated onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) plates supplemented with 0.05% chloramphenicol and onto brain heart infusion agar (BHI) plates supplemented with 5% dextrose. The plates were then incubated at two different temperatures (25–27°C and 35–37°C). After 12 days of incubation, cottony white colonies became visible on both media. Microscopic analysis of the colonies revealed the presence of hyphae and round, thick-walled, tuberculated macroconidia measuring 8–14μm in diameter, consistent with H. capsulatum (Fig. 3). In order to confirm this identification, fungal DNA was extracted from a small portion of the colony and submitted to nested-PCR analysis, followed by DNA sequencing, which confirmed the identification of the isolate as H. capsulatum var capsulatum.8,13 The patient was diagnosed with systemic disseminated histoplasmosis and was treated with 400mg/day of itraconazole (200mg twice a day). After three weeks of treatment, the overall condition of the patient improved significantly; some skin lesions had formed blackened blood scabs, while others had completely healed. After 6 weeks of treatment (+45 days), the patient was in good health; the lesions on the skin had nearly disappeared and no new lesions had appeared. The patient completed five months of treatment, and all new cultures and direct microscopic examination of new skin biopsies were negative for H. capsulatum.

Epidemiology data show that this fungus can be found from latitude 45° North to latitude 30° South.3 Vietnam is not within the epidemiological area of the disease, but some cases of lung disease have been reported.8,12,13 The first reported case, in 1962, was in a patient from the South of Vietnam.12 In Northern areas of Vietnam, 26 patients suffering lung infections (15 with HIV) had antibodies against H. capsulatum, detected by indirect ELISA, and 9 cases were diagnosed by nested PCR, followed by sequencing.8 The true prevalence of histoplasmosis in the Asia-Pacific area is poorly documented; improving and strengthening the knowledge on deep fungal diseases, as well as the management of the standard methods on mycological diagnosis, is necessary in this region (1, 6, 8). In this case study, the source of the patient's H. capsulatum could not be determined.

Acute disseminated histoplasmosis is rarely reported because clinical manifestations are not pathognomonic and difficult achieving a proper diagnosis. Histoplasma affects the reticuloendothelial system, which leads to clinical lesions in liver, spleen, lymph nodes, adrenal glands, skin, and mucous membranes. H. capsulatum (H. capsulatum var. capsulatum and H. capsulatum var. duboisii) can also form papules or centrally ulcerated pustular lesions that become covered by a crust with blackened blood scabs, surrounded by thick dry skin, sometimes accompanied by gangrene and nearby adenopathies without pain or itching.5,11 The patient from the current report also had the reticuloendothelial system affected, but the associated symptoms were neglected until skin lesions were visible.

According to Bosshard, dimorphic fungi take the longest time to grow, six weeks on average, while it takes approximately four weeks to culture Histoplasma from blood specimens.4 We suppose that the high concentration of the fungal cells in our sample contributed to a short time of incubation. We also added 5% dextrose to BHI to shorten the time of incubation. This action could potentially contribute to increase the chance of fungal growth since specimens from skin lesions may yield a lower growth rate of Histoplasma when compared to bronchial lavage fluid from acute lung lesions.10 However, we were not able to obtain the yeast phase of this fungus at 37°C. Kauffman recommends to perform PCR following the culture at 25°C because of its high sensitivity and very low chance of false positive results. This author suggests that, in order to confirm the species identification, a subculture at 35–37°C to obtain the yeast phase is not necessary.10 Using these techniques the time to arrive at a final diagnosis can be substantially shortened.

We describe the isolation and identification of H. capsulatum causing disseminated skin disease in a non-HIV/AIDS patient from Vietnam. This case underlines the importance of histoplasmosis suspicion in patients showing compatible symptoms, even in the absence of immunosuppressive conditions. The latter agrees with previous reports.5,11 The patient's condition greatly improved after being treated with itraconazole for three weeks and completing a modified five-month treatment, according to clinical guidelines.18 His condition remained stable and no recurrence of histoplasmosis, neither clinical nor microbiological, was observed.