Few studies exist on prevalence of fungemia by Candida orthopsilosis, with variable results.

AimsTo study the incidence, epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility of C. orthopsilosis strains isolated from fungemias over two years at a tertiary hospital.

MethodsCandidemia episodes between June 2007 and June 2009 in a university hospital (Puerta del Mar, Cádiz, Spain) were studied. The strains initially identified as Candida parapsilosis were genotypically screened for C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, C. orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis, and their antifungal susceptibility was evaluated.

ResultsIn this period 52 cases of candidemia were documented. Of the 19 strains originally identified as C. parapsilosis, 13 were confirmed as C. parapsilosis sensu stricto and 6 as C. orthopsilosis. Of the 52 isolates, the most frequent species were Candida albicans (30.8%), C. parapsilosis sensu stricto (25%), C. orthopsilosis, Candida tropicalis and Candida glabrata in equal numbers (11.5%). C. orthopsilosis isolates were susceptible to amphotericin B, caspofungin, voriconazole and fluconazole, with no significant differences in MIC values with C. parapsilosis sensu stricto. The source of isolates of C. orthopsilosis were neonates (50%) and surgery (50%), and 100% were receiving parenteral nutrition; however C. parapsilosis sensu stricto was recovered primarily from patients over 50 years (69.2%) and 46.1% were receiving parenteral nutrition.

ConclusionsThese findings show that C. orthopsilosis should be considered as human pathogenic yeast and therefore its accurate identification is important. Despite our small sample size our study suggests that a displacement of some epidemiological characteristics previously attributed to C. parapsilosis to C. orthopsilosis may be possible.

Apenas se han publicado estudios sobre la prevalencia de los episodios de fungemia por Candida orthopsilosis, y sus resultados han sido variables.

ObjetivosExaminar la incidencia, epidemiología y sensibilidad a antifúngicos de las cepas de C. orthopsilosis aisladas de fungemias en un periodo de 2 años en un hospital de asistencia terciaria.

MétodosEntre junio de 2007 y junio de 2009, en el Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar (Cádiz, España) se estudiaron todos los episodios de fungemia. Las cepas identificadas inicialmente como Candida parapsilosis se genotipificaron para su clasificación como C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, C. orthopsilosis y Candida metapsilosis, y se testó su sensibilidad a los antifúngicos.

ResultadosDurante este periodo, se documentaron 52 episodios de fungemia. De las 19 cepas identificadas originalmente como C. parapsilosis, 13 fueron C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, y 6 C. orthopsilosis. De los 52 aislamientos, las especies más frecuentes fueron Candida albicans (30,8%), C. parapsilosis sensu stricto (25%) y C. orthopsilosis (11,5%), y Candida tropicalis y Candida glabrata fueron aisladas en igual número. Todos los aislamientos de C. orthopsilosis fueron sensibles a anfotericina B, caspofungina, voriconazol y fluconazol, sin diferencias significativas en las concentraciones inhibitorias mínimas obtenidas con C. parapsilosis sensu stricto. Los aislamientos de C. orthopsilosis procedían de recién nacidos (50%) y de pacientes sometidos a cirugía (50%). El 100% de los pacientes recibía nutrición parenteral; sin embargo, el foco de C. parapsilosis sensu stricto procedía, ante todo, de pacientes de más de 50 años de edad (69,2%), y el 46,1% recibía nutrición parenteral.

ConclusionesLos resultados del presente estudio revelan que C. orthopsilosis debe considerarse una levadura patogénica para el ser humano y, por esta razón, es importante su identificación. A pesar del pequeño tamaño de la muestra, el presente estudio evidencia el desplazamiento a C. orthopsilosis de algunas características epidemiológicas atribuidas previamente a C. parapsilosis.

Candidemia has emerged as a serious threat to hospitalized patients,1,2 and non-Candida albicans Candida species are becoming increasingly prevalent.14–16Candida parapsilosis is one of the most common yeasts involved in invasive candidiasis10 and is frequently transmitted horizontally via contaminated external sources such as medical devices or fluids, the hands of health care workers, prosthetic devices, and catheters.24 Recent studies have reported an association between C. parapsilosis fungemias and the use of indwelling devices and parenteral nutrition, found frequently in patients admitted to neonatal or surgical ICUs.17

Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis are recently described species phenotypically indistinguishable from C. parapsilosis.21 Retrospective epidemiological studies have been undertaken to screen for C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis among isolates previously identified as C. parapsilosis,8,12,13,22 in which important epidemiological variations have been found. Studies on these species are necessary to clarify their incidence and epidemiology.

The aim of this work is to analyze the incidence, epidemiological data and sensitivity to antifungals of C. orthopsilosis and C. parapsilosis sensu stricto isolates from fungemia and the relation with all the Candida species isolated from blood cultures over a two-year period in a Spanish tertiary care hospital.

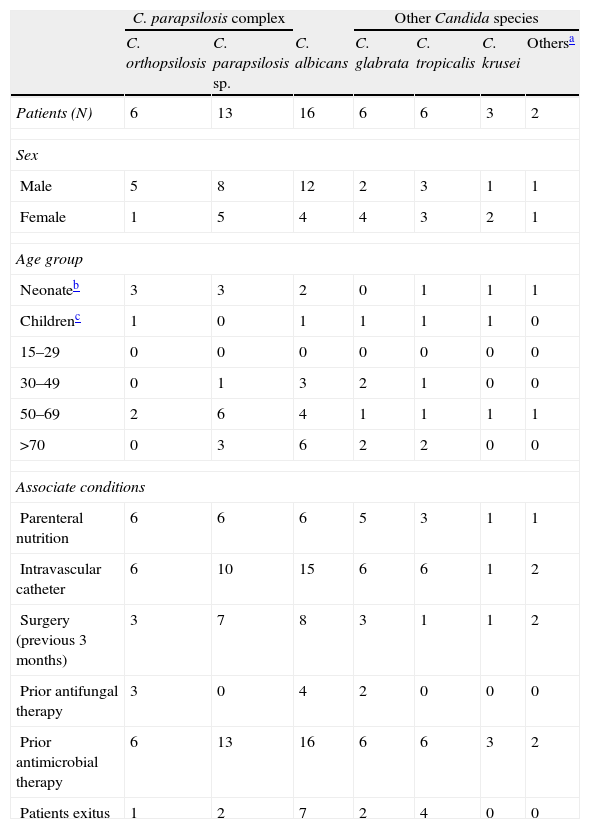

Material and methodsAll the fungemia episodes between June 2007 and June 2009 in a tertiary university Hospital (Puerta del Mar, Cádiz, Spain) were studied and some variables were analyzed according to a pre-established protocol (Table 1).

Comparison of sex, age and associated conditions of 52 patients with candidemia by C. orthopsilosis, C. parapsilosis, C. albicans, and other Candida species.

| C. parapsilosis complex | Other Candida species | ||||||

| C. orthopsilosis | C. parapsilosis sp. | C. albicans | C. glabrata | C. tropicalis | C. krusei | Othersa | |

| Patients (N) | 6 | 13 | 16 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 5 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Age group | |||||||

| Neonateb | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Childrenc | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 15–29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 30–49 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 50–69 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >70 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Associate conditions | |||||||

| Parenteral nutrition | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Intravascular catheter | 6 | 10 | 15 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Surgery (previous 3 months) | 3 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Prior antifungal therapy | 3 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Prior antimicrobial therapy | 6 | 13 | 16 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Patients exitus | 1 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

Blood culture samples were processed using the Wider System (Wider, Francisco Soria Melguizo, Madrid, Spain) and subcultured on Sabouraud and CHROMagar Candida plates (CHROMagar, Paris, France). A total of 52 Candida spp. were isolated from 52 different patients and 19 of these strains were originally identified as C. parapsilosis by API ID 32C (bioMérieux, Madrid, Spain).

Molecular identification of C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, C. orthopsilosis, and C. metapsilosis was carried out in the Microbiology laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, and assisted by the Facility of Bioscience Applied Techniques (STAB, Extremadura University, Spain), according to Chen et al.5 DNA of the 19 isolates and the control strains C. parapsilosis sensu stricto ATCC 1449, C. orthopsilosis CECT 13011 and C. metapsilosis CECT 13010 was extracted using a MasterPure™ Yeast DNA Purification Kit (EPICENTRE, Madison, WI). PCR with the universal primers ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) was used to amplify the 5.8S RNA gene and the flanking ITS1 and ITS2 region. All ITS sequences were submitted to the BLAST program of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Web site (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed using the Sensititre YeastOne panel-YO-7 (TREK Diagnostic Systems, Izasa, Madrid, Spain).

ResultsDuring the study period, 52 Candida spp. were isolated from blood cultures. The most frequently isolated species was the C. parapsilosis complex (36.5%) – C. parapsilosis sensu stricto (25%) and C. orthopsilosis (11.5%) – followed by Candida albicans (30.8%), and with the same number Candida tropicalis and Candida glabrata (11.5%) (Table 1); no cases of C. metapsilosis were isolated. Episodes of fungemia were most frequently observed in patients from the following departments: ICUs (21.2%), general surgery (21%), neonatology (15.4%) and internal medicine (7.7%).

Gender, age and associated conditions of the 52 patients with candidemia are shown in Table 1. Prior antibacterial therapy was administered in 100% of the cases of candidemia; presence of intravascular catheter fluctuated from 77 to 100%, except in Candida krusei, a species in which the presence of hematological malignancies is noted. C. parapsilosis complex fungemias share several risk factors but with some differences: C. orthopsilosis fungemia was related mainly with parenteral nutrition (100%) and neonates (50%); C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, however, was recovered primarily from patients aged at least 50 years (69.2%) and only 46.1% were receiving parenteral nutrition (P=0.02).

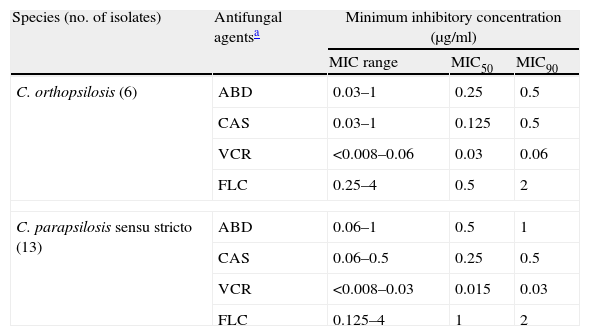

Antifungal susceptibility testing results of C. parapsilosis sensu stricto and C. orthopsilosis for fluconazole, voriconazole, amphotericin B and caspofungin are summarized in Table 2. All isolates were found to be susceptible to the four antifungal agents tested, followed MIC breakpoints by established CLSI guidelines.6 There were no significant differences in MIC values between both species. However, by using the new breakpoints of fluconazole proposed by the EUCAST,20 there is one isolate of C. parapsilosis sensu stricto which is susceptible-dose dependent to fluconazole (MIC=4).

In vitro susceptibilities of C. orthopsilosis and C. parapsilosis sensu stricto bloodstream isolates to four antifungal agents.

| Species (no. of isolates) | Antifungal agentsa | Minimum inhibitory concentration (μg/ml) | ||

| MIC range | MIC50 | MIC90 | ||

| C. orthopsilosis (6) | ABD | 0.03–1 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| CAS | 0.03–1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | |

| VCR | <0.008–0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

| FLC | 0.25–4 | 0.5 | 2 | |

| C. parapsilosis sensu stricto (13) | ABD | 0.06–1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| CAS | 0.06–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| VCR | <0.008–0.03 | 0.015 | 0.03 | |

| FLC | 0.125–4 | 1 | 2 | |

Nosocomial infections by C. parapsilosis have increased considerably and high rates of candidemia by C. parapsilosis can be attributed to nosocomial transmission.9,24C. parapsilosis is notorious for its capacity to grow in total parenteral nutrition, for nosocomial spread by hand carriage, and for its persistence in the hospital environment.24 Incidence varies from one study to another, due fundamentally to the type of the population studied. In children's hospitals incidence reaches up to 60% of the candidiasis isolated,7,18 whereas in adults the incidence is lower, with references of 20–30%.1,16 In our study we found an incidence of fungemia by C. parapsilosis complex of 36.5%, which reached 54.5% in neonates, percentages which vary with the identification of new species. In neonates C. orthopsilosis provided 50% of the isolates and C. parapsilosis sensu stricto 23%, the possible source of infection being exogenous colonization by neonatology staff. On the other hand, 69.2% of C. parapsilosis sensu stricto was recovered from patients aged at least 50 years as opposed to 33% of C. orthopsilosis. Our results indicate that the frequency of the species differ depending on the age of the patients, in agreement with Tay et al.23 who found a higher frequency of C. orthopsilosis candidemia in pediatric patients compared to adult patients.

The existence of three genetically different groups in C. parapsilosis was described by Lin et al.11 and the groups were subsequently classified as different species by Tavanti et al.21 as C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis. In the present study we found, after molecular identification of 19 C. parapsilosis complex isolates of fungemia, that 31.5% of the isolates phenotypically identified as C. parapsilosis were C. orthopsilosis. Studies performed on incidence of C. orthopsilosis within the complex group presented variable results3,13,19,21,23 fluctuating from 2.37%18 to 25.9%19,21, which is similar to our results. Our findings show a high prevalence of fungemia by C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, and by C. orthopsilosis, second and third species in frequency after C. albicans. In one case of fungemia by C. orthopsilosis, identical isolation was obtained on repeating the hemoculture a week after treatment. No isolates of C. metapsilosis were obtained, a species which has been reported to be rarely recovered from clinical samples.17

The results of antifungal susceptibility testing showed that the C. parapsilosis sensu stricto and C. orthopsilosis isolates tested in this study were susceptible to amphotericin B, caspofungine, fluconazole and voriconazole. According to previous studies,4,15,17 all the isolates show a high level of susceptibility to all the agents tested. Some authors find in C. orthopsilosis greater resistance to voriconazole3, and greater susceptibility to echinocandins3,8; in the case of our strains, a slight displacement of MICs in this sense was observed. In general, there was no statistically significant difference between the susceptibility profile of the two species either with the azoles (fluconazole, voriconazole) or with amphotericin or caspofungin.

In this study we report a notable prevalence of the recently described species C. orthopsilosis from blood culture, and we point to the clinical relevance of these newly described yeasts. Although molecular methods are not routinely available, identification is easily performed by ITS sequencing. Differentiation of the new species allowed us to define the epidemiology of candidemia by C. parapsilosis sensu stricto and C. orthopsilosis. The low number of C. orthopsilosis isolates found during the period studied merits additional investigation concerning its epidemiology, since some of the characteristics previously attributed to infections by C. parapsilosis, such as presence in neonates, may be displaced toward C. orthopsilosis.

Ethical responsibilitiesConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of the data from the patients, and that all patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors report no conflicts of interest.

This study was supported by grants from the Junta de Extremadura, Spain, project PRI09A021 and Grant GR10031 to Investigation Groups; FEDER and CIBER-BBN funds. We are grateful to J. McCue for the preparation of the manuscript, and to Bioscience Applied Techniques Services of SAIUEx for technical and human support (financed by UEX, Junta de Extremadura, MICINN, FEDER and FSE).