Phaeohyphomycosis can be caused by a number of different species, being the most common Alternaria alternata and Alternaria infectoria. The biggest risk factor for the development of the infection is immunosuppression.

AimsWe present the case of a 64-year-old male renal transplant patient who came to hospital for presenting a tumour in the Achilles region which had been gradually growing in size.

MethodsA skin biopsy was taken for histological study and culture of fungi and mycobacteria. Blood tests and imaging studies were performed.

ResultsHistopathology study and cultures identified A. infectoria as the causal agent. Imaging studies ruled out internal foci of infection. The lesion was surgically removed with no signs of recurrence after 24 months of follow-up.

ConclusionsThere are no treatment guidelines at present for cutaneous and subcutaneous Alternaria spp. infections. Various systemic antifungals have been used, either in combination with surgical removal or alone, with varying results. Surgery alone could be useful in the treatment of solitary, localised lesions in transplant patients in whom there are difficulties in controlling immunosuppression.

La feohifomicosis está causada por diversas especies de hongos, siendo las más habituales Alternaria alternata y Alternaria infectoria. El factor de riesgo principal en la aparición de la infección es la inmunosupresión.

ObjetivosPresentamos el caso de un hombre de 64 años de edad, sometido a un trasplante renal, que se presentó en el hospital con un tumor en la región del tendón de Aquiles que había aumentado gradualmente de tamaño.

MétodosSe obtuvo una biopsia de piel para estudio histológico y cultivo de hongos y micobacterias. Se efectuaron análisis de sangre y estudios de diagnóstico por imagen.

ResultadosEl estudio histopatológico y los cultivos permitieron la identificación de A. infectoria como del patógeno causal. Los estudios por imagen descartaron focos internos de infección. Se procedió a la exéresis quirúrgica de la lesión sin signos de recidiva después de 24 meses de seguimiento.

ConclusionesEn la actualidad no se dispone de guías de tratamiento para las infecciones cutáneas y subcutáneas por Alternaria spp. Se han utilizado diversos antimicóticos sistémicos, combinados con la exéresis quirúrgica o solos, con diferentes resultados desiguales. La cirugía sola podría ser útil en el tratamiento de las lesiones localizadas, solitarias, en los pacientes sometidos a un trasplante en los que es difícil controlar la inmunosupresión.

The increase in the number of transplant patients, in conjunction with improvement in their long-term management, has meant a rise in the incidence of opportunistic fungal infections.13 Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare cutaneous or systemic infection caused by the dematiaceous family of pigmented fungi. Over 100 species have been isolated as aetiological agents, with the most common being Alternaria, Curvularia, Exserohilum and Bipolaris.1 Although there have been some cases in immunocompetent patients,15 most cases of phaeohyphomycosis are found in immunosuppressed patients, particularly transplant recipients. We present a case of subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis caused by Alternaria infectoria in a renal transplant patient which was treated exclusively by surgery.

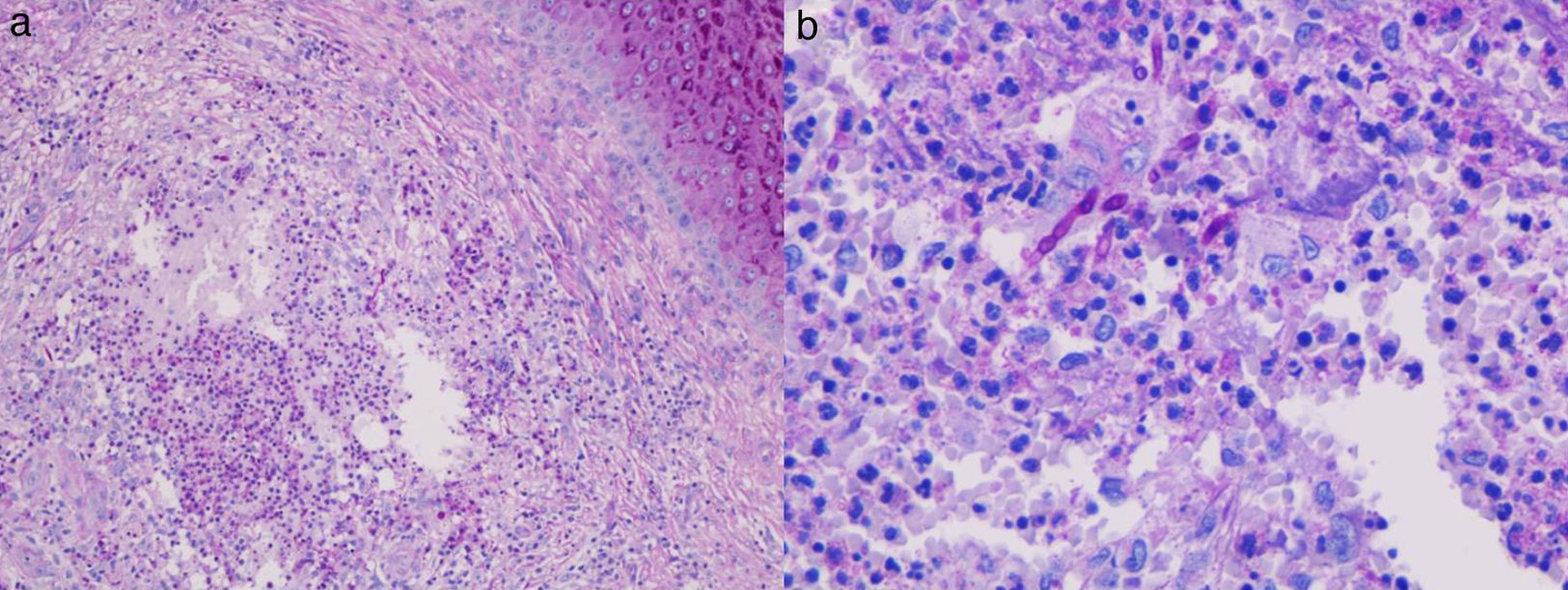

ReportThis was a 64-year-old male who was referred to our clinic following the development of an asymptomatic tumour formed by purplish nodules with dark pigmented areas in the Achilles area of his right foot (Fig. 1). The patient's relevant medical history included kidney transplantation 8 years previously as a result of end-stage renal failure caused by hypertensive nephropathy. He was on treatment with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone to prevent rejection of the transplanted organ. No inoculation events were identified. On examination, no fever, lymphadenopathy or systemic symptoms were detected. Blood tests found no abnormalities. A skin biopsy was taken for histology and culture for fungi and mycobacteria. The histopathology study found pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis formed by suppurative granulomas containing large quantities of neutrophils, lymphocytes, epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells. Inside the granulomas, areas of necrosis and PAS-positive septate extracellular structures with branching hyphae were observed (Fig. 2). A portion of the biopsy was spread on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SAB) plus chloramphenicol and incubated at 30°C; a pure culture was obtained after 48h of growth.

(a) Histological examination showing granulomatous infiltrate with areas of necrosis in the dermis (periodic acid–Schiff stain, 20× original magnification). (b) At greater magnification, the granulomas were seen to be composed of neutrophils, multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes, with thick-walled septate structures identified as fungal elements (periodic acid–Schiff stain, 40× original magnification).

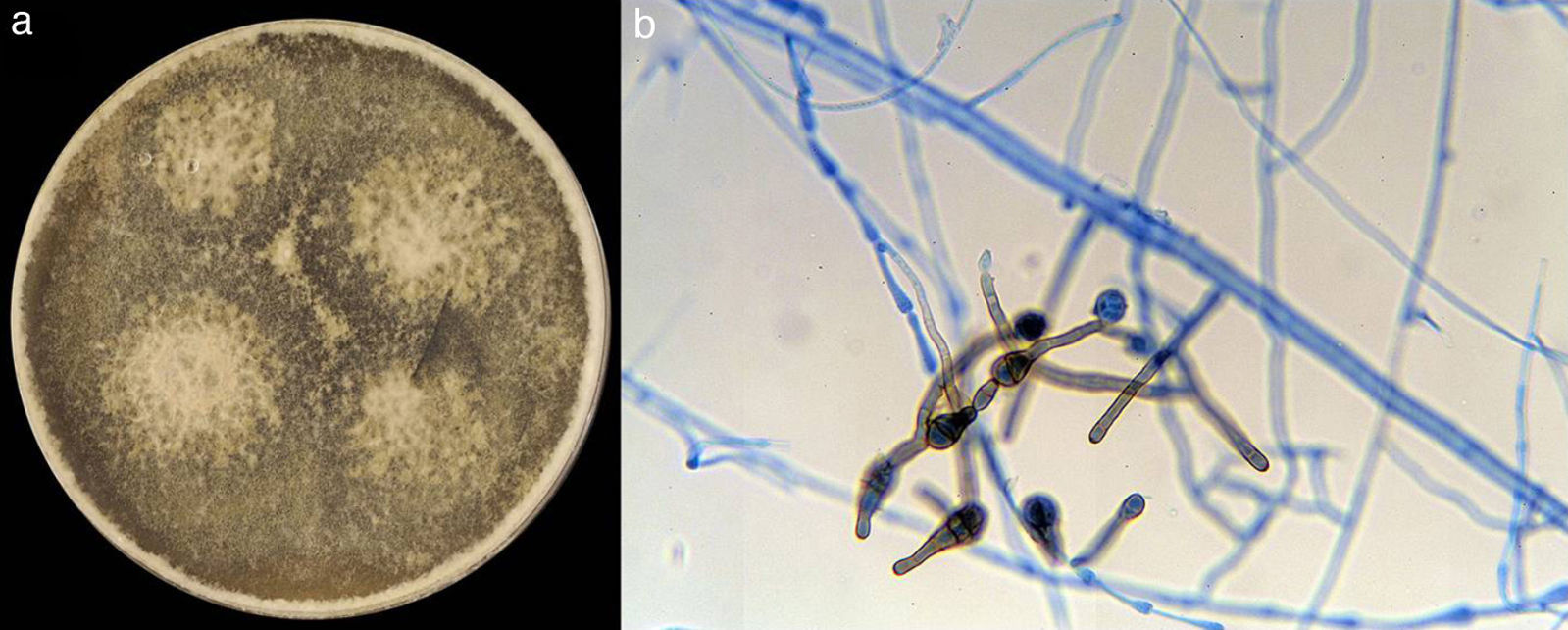

Colonies were initially felty, later turned greyish, and then olivaceous grey, with the same colour on the reverse. SAB cultures showed only a few conidia. Sporulation was induced by subcultures on potato dextrose agar, and the presence of dark brown, ovoid conidia with transverse and oblique septation arising in strongly branched chains was observed (Fig. 3), indicative of an Alternaria isolate. For identification purposes, the fungus was cultured on potato carrot agar (PCA; 20g potato, 20g carrot, 18g agar, 1000ml tap water) and incubated at 25°C and 37°C in the dark. The colonies on PCA at 25°C were rapid-growing, grey-to-olivaceous and felty, reaching a diameter of 51–52mm in 7 days. Scant growth was observed at 37°C. Microscopically, the fungus was characterized by short unbranched conidiophores from which sprouted long, often branched, conidial chains due to the development of secondary conidiophores through apical extension of a conidium. The conidia were brown-to-dark-brown, smooth-walled or finely warty, with a predominance of transverse septa, ovoid or ellipsoidal, often with apical beaks, measuring 13–46μm×8–11.5μm. On the basis of the above characteristics and on comparison with Alternaria reference strains (A. infectoria CBS 210.86, Alternaria alternata CBS 603.78), the isolate was identified as A. infectoria.4 Living cultures of the fungus were deposited in the fungal collections at the Medical Faculties in Córdoba and Reus (Spain) as CLFMC 16433 and FMR 9517 respectively.

Imaging studies, which ruled out internal foci of infection, were performed. In view of its size and the fact that it was well delimited, the lesion was removed surgically. The patient refused any kind of additional drug treatment. After 24 months of follow-up, no recurrence of the lesion has been detected.

DiscussionPhaeohyphomycosis can be caused by different species, being A. alternata and A. infectoria the most commonly isolated.12 The main route of transmission is traumatic inoculation by thorns, splinters or other soil substrates, vegetation or animals.5

Alternaria skin infections can occur in immunocompetent people, but all the published cases up to now caused by A. infectoria have been in immunosuppressed patients.1–3,5,6,8–11,14,16 Fifteen cases out of 18 cases were transplant patients, being new kidney recipients the most common ones (8/15).

Diagnosis is mainly based on clinical, histopathological and microbiological studies. A. infectoria skin infections adopt a very varied clinical morphology which is related to the route of transmission. When the infection occurs by inoculation, the lesions appear as solitary erythematous plaques with an ulcerated/crusty centre. Similar lesions were observed in our case although they were not associated with any trauma. In disseminated forms, multiple painful papules or nodules, which can develop into a sporotrichoid pattern, tend to appear on the skin.7 The histopathology can vary according to the point at which the skin biopsy is taken. Findings range from a mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in early phases to the formation of suppurative or sarcoidal granulomas in more established lesions. In our case, isolation and comparison with the strain type A. infectoria allowed us to confirm the identification of the isolate.

There are currently no standardised treatments for cutaneous and subcutaneous infections caused by Alternaria. In those cases where it is possible, reduction in the immunosuppression can be sufficient to resolve the lesions, although the long-term use of systemic itraconazole is recommended. One of the problems with this drug, however, is the potent inhibition of the metabolism of calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) by the cytochrome P450 (CYP3A4). These drugs are widely used to control transplant patients and so concomitant use of imidazoles can make management difficult and require plasma levels of CNI to be monitored. Some patients do not respond to drug treatment and surgical removal is required.1,2,6,8,9,14 In our case, we decided on surgery since the lesion was well delimited and only the skin was affected. After surgery, antifungal treatment for around 6 months is recommended, although this option was refused by our patient.

In well-delimited single lesions, and in the absence of systemic foci, complete surgical removal may be an effective treatment for localised forms of phaeohyphomycosis acquired by direct inoculation. Nevertheless, follow-up needs to be long-term due to the risk of late recurrence.1 Clinical trials are needed in order to produce consensus therapeutic guidelines for the standardised management of Alternaria spp. skin infections.

Funding sourcesNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.