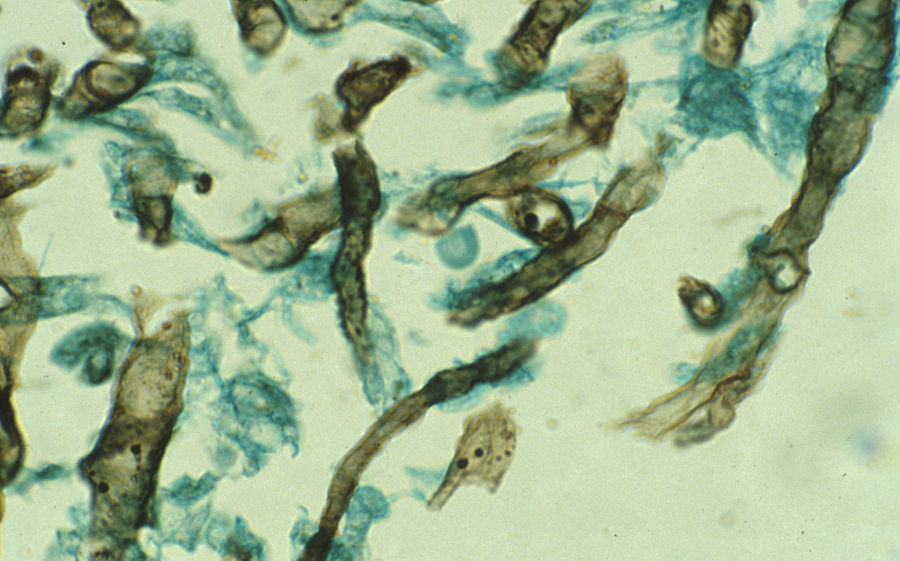

Oomycetes are eukaryotic, filamentous, fungal-like microorganisms that are phylogenetically grouped with diatoms and brown algae in the SAR (Stramenopiles–Alveolata–Rhizaria) supergroup, far from the members of the Kingdom Fungi. Among the most important oomycetes, some Phytophthora species stand out as the cause of devastating plant diseases, such as Phytophthora infestans, known for triggering the potato famine in Ireland in the mid-19th century. Today, this species remains a major threat to global food security, causing severe losses in potato and tomato crops. Some aquatic oomycetes are animal pathogens, such as Saprolegnia parasitica, which causes saprolegniosis in fish (Fig. 1), a major threat to aquaculture. This species is an important problem in the fish farming industry in Europe, Chile, Canada and Asia. In addition to fish, amphibian, crustacean and aquatic insect species are also highly susceptible to saprolegniosis. There is conclusive evidence that Saprolegnia species are a major cause of mortality in amphibian populations worldwide, threatening some endangered species. In contrast to their terrestrial counterparts, aquatic oomycetes remain poorly studied.2

Indeed, despite the importance of these aquatic pathogens, their taxonomy has not yet been satisfactorily elucidated. The genus Saprolegnia encompasses around twenty species. The identification of these species has been traditionally based on the morphology of asexual and sexual structures, such as the zoosporangium, the oogonium or the antheridium. In some cases, these taxonomic characters are often absent or ambiguous in the descriptions used to define species. To improve the classification and identification of the genus Saprolegnia, a standardised protocol for the description of its species has recently been proposed.3 This protocol includes good culture practices and proper preservation of the holotype. The characterisation and analysis of useful DNA sequences of these pseudofungi for taxonomical purposes is currently underway.

Saprolegniosis is a disease generally restricted to the epidermis and dermis of fish, but can affect deeper tissues. In the skin, the main lesions are clearly visible as white or grey patches that may appear over the entire body surface and are characterised by a cottony-looking growth formed by tufts of aseptate hyphae (Fig. 2). This growth disrupts the osmoregulatory mechanism of the fish and, unless treated, the infection is usually fatal. A recent retrospective study has detailed the most frequent distribution patterns of the skin lesions in brown trout (Salmo trutta) either from some rivers and a fish farm in the province of León, Spain.1 The number of lesions, the percentage of body surface area affected and the number of fish with necrotic lesions were much lower in farmed trout than in wild trout. However, farmed trout had received regular preventive chemical treatment for saprolegniosis. In river trout, lesions were observed anywhere on the body surface, including the eyes and fins. In farmed trout, the most frequently affected area was the adipose fin.

Until 2002, S. parasitica was kept under control with applications of malachite green. However, its use has been banned worldwide due to its toxicity, leading to an increase in Saprolegnia infections in salmonid aquaculture. Current control methods involve treatments with formalin-based products, which are also expected to be banned in the EU in the very near future. Probiotics are currently under intensive research as an alternative to the conventional chemicals used in aquaculture.

Conflict of interestAuthor has no conflict of interest.

Financial support came from Servei Veterinari de Bacteriologia i Micologia of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

These Mycology Forum articles can be consulted in Spanish on the Animal Mycology section on the website of the Spanish Mycology Association (https://aemicol.com/micologia-animal/).