Blastomycosis is a systemic fungal infection that most commonly affects dogs, and to a lesser extent humans and other mammals. This mycosis is endemic in certain regions of the United States and Canada around the Great Lakes, and in the Ohio and in the Mississippi river valleys. Disease incidence rates are estimated to be eightfold greater in dogs than in humans. For this reason dogs may serve as sentinels for human exposure. Blastomyces dermatitidis has been known, for many years, as the only causative agent of this disease. Recently, in order to identify risk factors for B. dermatitidis infection in dogs and humans, the prevalence and distribution of canine blastomycosis cases in Michigan have been investigated.3 Michigan has one of the greatest densities of lakes, ponds, rivers, and streams in the USA. Contrary to previous reports, most blastomycosis cases were acquired in the Upper Peninsula or in the northernmost regions of the Lower Peninsula. Travel or residence north of the 45th parallel was the most important predictor for blastomycosis occurrence. The use of dogs for hunting was also a significant risk factor. Hunting is also a risk factor for blastomycosis in humans. Both humans and dogs that hunt are presumably more likely to have exposure to infectious conidia. The etiological agents of blastomycosis are dimorphic fungi that exist as hyphal forms in the environment and as yeasts in tissue. The hyphal form produces infectious conidia that become aerosolized when soil is disrupted. Once inhaled, the conidia are phagocytized by alveolar macrophages and develop into the yeast phase. Pulmonary manifestations occur in greater than 80% of the affected dogs, and respiratory abnormalities are the most common reasons for clinical evaluation in these animals. Lymphatic, ocular, osteoarticular, and dermatologic involvement are also common. Unfortunately, diagnoses are often delayed due to lack of clinician awareness and similarities with other disease processes. Mortality rates can approach 40% in dogs, and relapses occur in up to 20% of canine patients despite months of antifungal therapy.

The ecological niche of B. dermatitidis reported includes sites with an acidic pH, high organic content, and close proximity to waterways. This fungus is extremely difficult to culture from the environment, so little is known about its environmental reservoirs. As culturing this species from the environment is often unsuccessful, previous studies have inferred the location of B. dermatitidis through epidemiologic data associated with outbreaks. In a recent study carried out in Minnesota,1 a culture-independent, PCR-based method to identify B. dermatitidis DNA in environmental samples was used, in order to characterize the unknown B. dermatitidis environmental niche. This study describes the find of environmental locations with high prevalence of B. dermatitidis. Furthermore, by combining molecular data with ecological niche modelling, these authors were able to predict the presence of this species in environmental samples with 75% accuracy and to define the characteristics of its environmental niche.

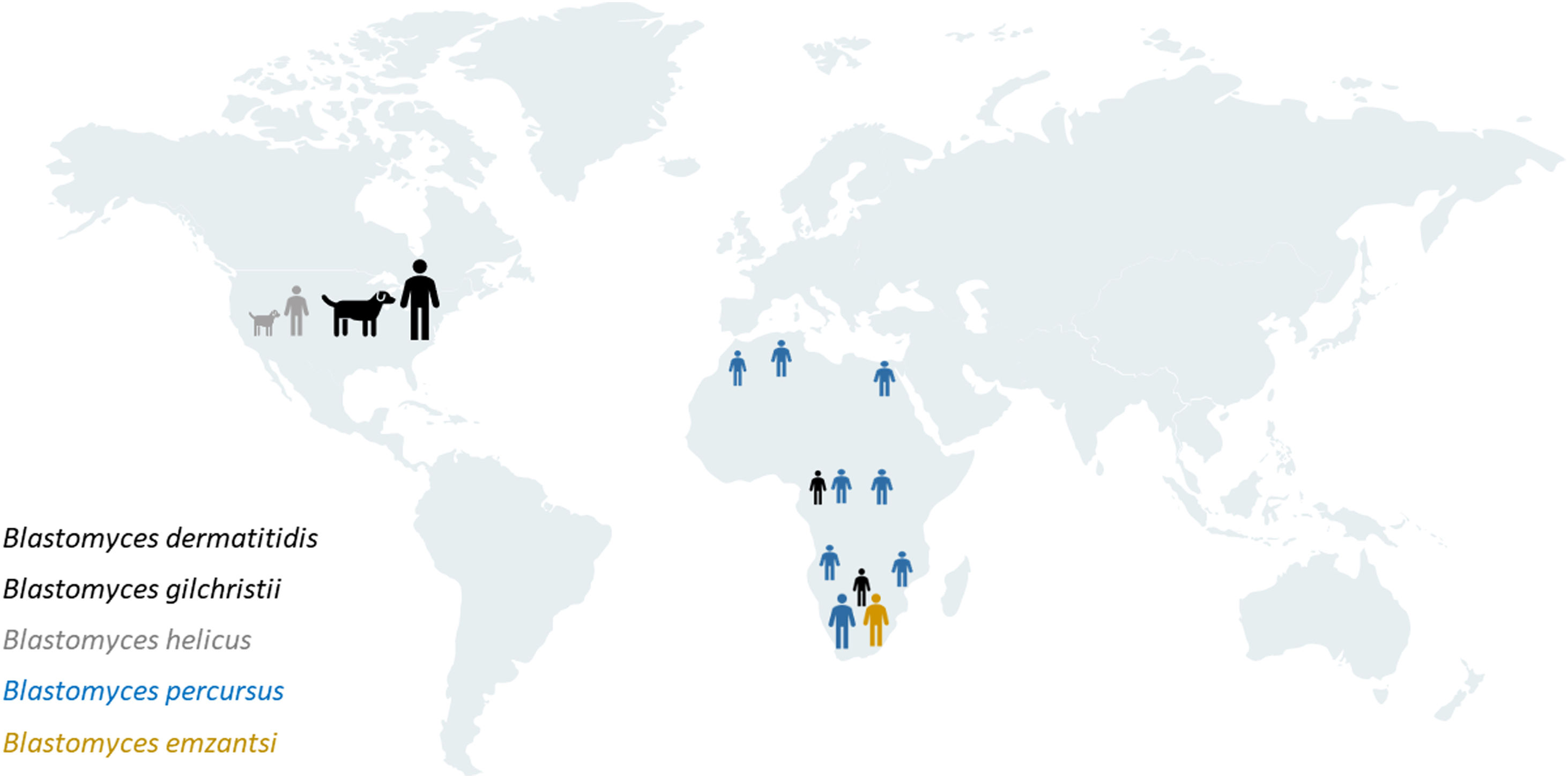

However, other species causing this mycosis have recently been described and their genetic and geographic diversity is greater than previously appreciated.2 In addition to B. dermatitidis and the cryptic species Blastomyces gilchristii, which cause blastomycosis in mid-western and various eastern areas of North America, atypical blastomycosis is occasionally caused by Blastomyces helicus in western parts of North America. Besides, this mycosis occurs throughout Africa and the Middle East in human beings, and is caused predominantly by Blastomyces percursus and, at least in South Africa, Blastomyces emzantsi, resulting in distinct clinical and pathological patterns of disease (Fig. 1). This interesting and detailed recent study confirms that the pathogens that cause blastomycosis in these countries are largely distinct from those causing the disease in North America. In this publication, the new species B. emzantsi is, precisely, described. Emzantsi means “south” in the isiXhosa language, referring to South Africa, the country of origin of the type species of this new taxon. Besides, this paper also includes a comprehensive literature search and review on human and veterinary cases of blastomycosis diagnosed or putatively acquired in Africa and the Middle East, covering seven publications on blastomycosis diagnosed in animals. In general, the information in these veterinary papers regarding the disease diagnosis and the identification of the fungal species involved is questionable as the findings are poorly detailed and, in the few cases where cultures were obtained, no molecular identification of the isolates was carried out. Moreover, none of the strains analysed in this study were recovered from animals, so the species involved in animal blastomycosis in these countries are unknown. At present, there are no reliable data on the occurrence of blastomycosis and its aetiology in domestic and wild animals in Africa and the Middle East.

Geographical distribution of species causing blastomycosis in man and dog. Note that the species causing blastomycosis in North America and Africa are different. At present, there are no reliable data on the occurrence of this mycosis in animals and its aetiology in Africa and the Middle East.2

Author has no conflict of interest.

Financial support came from Servei Veterinari de Bacteriologia i Micologia of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

These Mycology Forum articles can be consulted in Spanish on the Animal Mycology section on the website of the Spanish Mycology Association (https://aemicol.com/micologia-animal/).