Sporothrix species have proved to show high degrees of endemicity. Sporothrix globosa is the only pathogenic Sporothrix species that has till date been reported from China, where it is endemic in the northeastern provinces.

AimsWe report two cases of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis with diabetes mellitus as underlying disease in patients from the non-endemic area of China.

MethodsA 59-year-old farmer and a 60-year-old gardener were admitted in February and June 2014, respectively. Both patients were right-handed men and presented with progressive plaques and nodules, which they had for several years, involving the right upper extremity. Skin biopsy from the granuloma was taken and cultured on Sabouraud medium, and molecular identification based on the calmodulin region was performed. Antifungal susceptibility testing was also performed with the microdilution method.

ResultsBiopsy of the lesions showed the presence of infectious granuloma. The fungal cultures were identified as Sporothrix globosa by conventional methods, and confirmed by molecular identification. A subsequent course of oral antifungal therapy with low dosage of itraconazole was well tolerated and resolved the infection.

ConclusionsIdentification of fungal species and antifungal susceptibility testing are mandatory for epidemiological and therapeutic reasons. Early diagnosis of sporotrichosis is essential to prevent those sequelae when the disease progresses and provides highly effective methods for treating this emerging disease. Avoiding the exposure to plant material potentially contaminated with fungal spores should be recommended, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Las especies de Sporothrix han demostrado un alto nivel de endemicidad. Sporothrix globosa es la única especie patógena descrita hasta la fecha en China, donde es endémica en las provincias del nordeste.

ObjetivosSe describen dos casos de esporotricosis linfocutánea con diabetes mellitus como enfermedad de base, en pacientes procedentes de un área no endémica de China.

MétodosUn campesino de 59 años y un jardinero de 60 años de edad fueron atendidos en febrero y junio de 2014, respectivamente. Ambos eran varones, diestros y se presentaron con placas y nódulos de varios años de evolución, que afectaban a la zona superior del brazo derecho. Se tomaron biopsias de los granulomas de la piel, que fueron cultivados en medio de Sabouraud, y se realizó una identificación molecular basada en la región de la calmodulina. Se evaluó la sensibilidad a los antifúngicos mediante el método de microdilución.

ResultadosLa biopsia de las lesiones mostró la presencia de un granuloma infeccioso. Los hongos aislados en los cultivos fueron identificados como Sporothrix globosa por métodos convencionales, y confirmados mediante identificación molecular. La subsecuente administración de terapia antifúngica oral con bajas dosis de itraconazol fue bien tolerada y resolvió la infección.

ConclusionesLa identificación de las especies fúngicas y el análisis de la sensibilidad a los antifúngicos son necesarios por razones epidemiológicas y terapéuticas. El diagnóstico temprano de la esporotricosis es esencial para prevenir las secuelas que genera el progreso de la enfermedad y para ofrecer métodos altamente efectivos para el tratamiento de esta enfermedad emergente. Debe recomendarse evitar la exposición a material vegetal potencialmente contaminado con esporas fúngicas, especialmente en pacientes inmunocomprometidos.

Sporotrichosis is a subcutaneous mycosis caused by several species of the genus Sporothrix, viz. Sporothrix brasiliensis, Sporothrix globosa, Sporothrix mexicana, and Sporothrix luriei, in addition to the classical species Sporothrix schenckii.3,14,15,18,19,28,30 The disease is commonly associated with agricultural labor, gardening, construction work, or other activities that may increase the risk for traumatic introduction of propagules from the environment into the subcutaneous tissue.3 Sporotrichosis has a global distribution, but the causative agents are not proportionally distributed since the main pathogenic Sporothrix species have proven to show high degrees of endemicity. Sporothrix brasiliensis is known to be geographically limited to Brazil and is involved in an expanding zoonosis with preponderant feline transmission.21 The contemporary sapronotic outbreak with similar dimensions in China is caused by S. globosa, that exhibits a global distribution pattern.28

S. schenckii s. str., the genetically most variable species within the clade, has also a plant origin, with ecological similarities to that of S. globosa, but zoonoses with cats as prime susceptible hosts have also been observed.18

In China, sporotrichosis exists nationwide but is mainly observed in the Northeastern provinces.11,23,24,26,27S. globosa exhibited a global distribution with nearly identical genotypes and this species is the only pathogenic Sporothrix species that is thus far confirmed to occur in China, mainly causing fixed or lymphocutaneous infections without being vectored by animals, which are known to be the vectors in this country.28 Here we report two cases from the non-endemic area of China. These cases illustrate the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for atypical fungal infections with granulomatous appearance in patients with poor immune function, especially those individuals working outdoors and who are in close contact with plant materials.

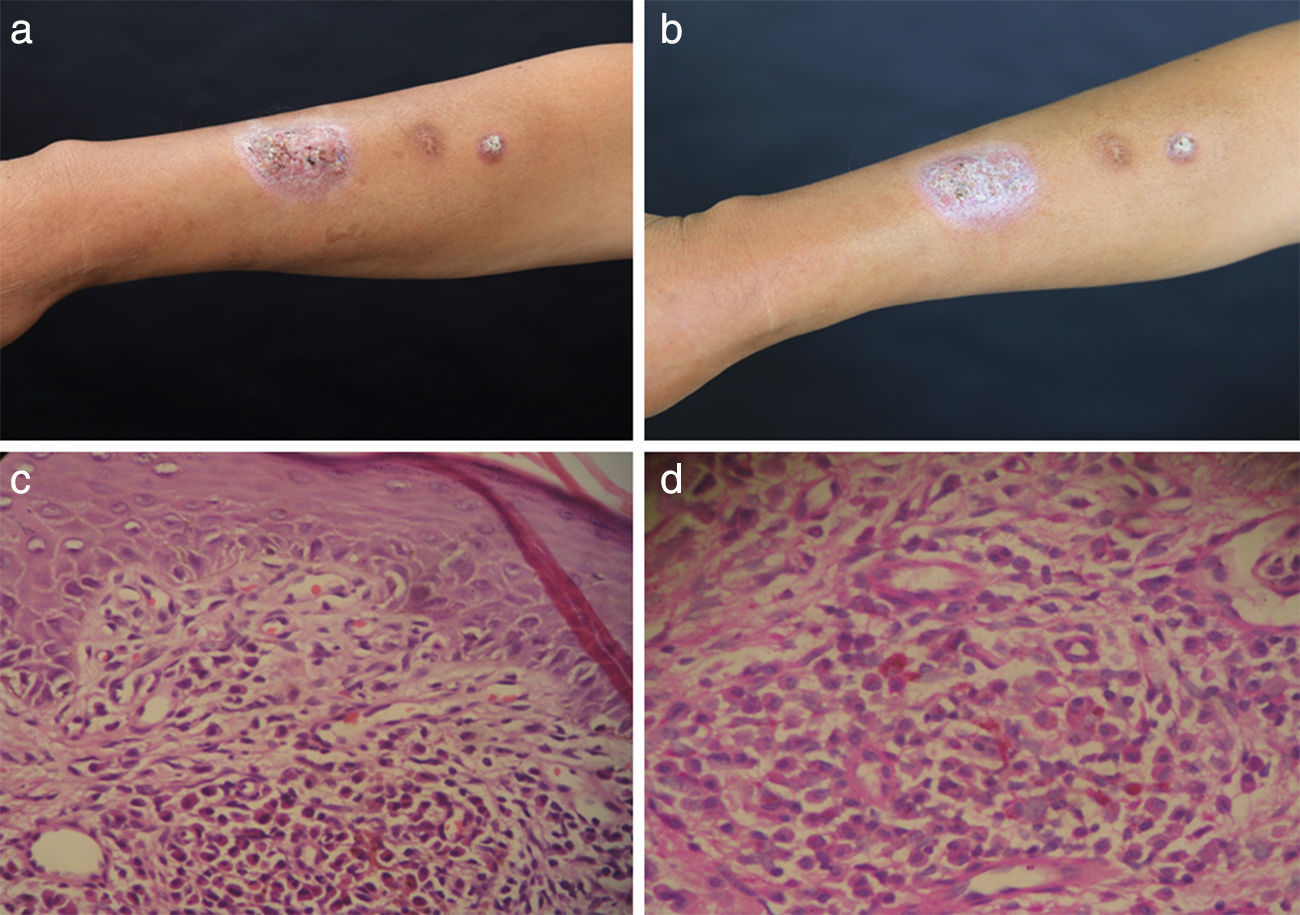

Case reportsPatient 1A 59-year-old, right-handed male Chinese farmer from Tianjin presented in February 2014 with plaques and multiple nodules on the right upper extremity. Three months before, he had noted a red-colored and bean-sized painless nodule on his right wrist. He was diagnosed with fibromas and underwent a surgical excision in a local hospital, but without signs of improvement. Approximately one month later, a new plaque with hyperplasia, granulomatous appearance, ulcers and burst emerged near the scar, which progressed gradually to a size of 3cm×1.5cm. Simultaneously, an additional red nodule was noted to appear proximally along the right arm. He had a history of contact with corn and wheat and denied any evident trauma and none of the family members had similar symptoms. The patient had a 10-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, for which he was intermittently treated with oral dimethyldiguanide tablets 250mg t.i.d. As a farmer he was frequently involved in breaking off corn cobs and daily in contact with reeds and wheat. Based on the pattern of progression of the lesions along lymphatic channels, there was a clinical suspicion of infection with microorganisms such as Sporothrix species and/or atypical mycobacteria.

Physical examination revealed a plaque with a size of 3cm×1.5cm on the flexor side of the right wrist, multiple visible nodules and several palpable but invisible subcutaneous nodules from soya size to fava bean size on the patient's right arm; the nodules were in various stages of evolution and appeared to spread along lymphatic channels (Fig. 1a–c).

The patient underwent follow-up evaluation. Fungal cultures of a skin biopsy yielded dark colonies on SDA medium, morphologically identified as Sporothrix globosa. Routine bacterial cultures and tests for acid-fast bacteria remained negative. Successive blood glucose level was 8.19–9.43mmol/l, which was above the normal range of 3.9–6.1mmol/l.

Molecular identification was performed by amplification and sequencing of the calmodulin (CAL) region as described before.17 A search of this sequence by using BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) demonstrated a 100% match with the type-strain of S. globosa CBS120340 (GenBank accession number AM116908).

In vitro antifungal susceptibility testing was performed with the CLSI recommended microdilution method (M38-A2) for the compounds itraconazole (ITR), terbinafine (TRB), voriconazole (VOR), amphotericin B (AMB) and caspofungin (CAS).6 For CAS the minimal effective concentration (MEC) was defined as the minimal antifungal concentration; for the other compounds the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) endpoints were determined as the lowest drug concentration that yielded no visible fungal growth. The experiment was carried out in duplicate. The MIC values against ITR, TRB, VOR and AMB were 8μg/ml, 2μg/ml, 16μg/ml and 8μg/ml, respectively, while the MEC value for CAS was 16μg/ml.

Histopathology findings included epidermal superficial scab, stratum spinosum hypertrophy, pseudoepithelioma hyperplasia, dermal angiectasis hyperemia, a large number of neutrophils lymphocytes cells and plasma cell infiltrates, and visible multinucleated giant cell (Fig. 1d). The PAS staining did not reveal the presence of fungal elements.

Therapy with oral itraconazole 100mg daily was initiated and lasted for 10 months until presently. The low dosage itraconazole regimen was well tolerated, and has finally resulted in the complete resolution of the lesion, but only small scars are left (Fig. 1d).

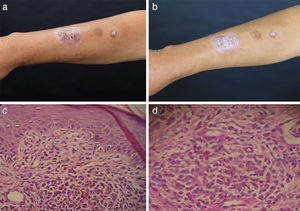

Patient 2A 60-year-old, right-handed male Chinese gardener from Tianjin was admitted in June 2014 to our hospital with multiple plaques on the right upper extremity. Three years before, he noticed a red-colored and pea-sized painless nodule with exudation on the back of his right hand. After one year of development of the lesion he received cryotherapy at a local hospital, but without improvement. The nodule gradually progressed to a plaque with hyperplasia, granulomatous appearance and exudation, reaching a size of 2.5cm×2.5cm, and simultaneously new nodules with hyperplasia began to appear along the right forearm. He went to another local hospital, where a biopsy was taken but without a conclusive diagnosis and treatment. He could not recall any trauma and none of the family members showed similar clinical signs. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus for three months, but without treatment.

Physical examination revealed two plaques, 2.5cm×2.5cm and 1cm×1cm in size, on the extensor aspect of the right forearm (Fig. 2a and b). The blood glucose levels were 6.8–6.9mmol/l (normal range: 3.9–6.1mmol/l). Histopathology showed the presence of epidermal hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, thickening of the stratum spinosum, basal cell focal liquefaction, upper dermis lymphocyte cells, plasma cells, neutrophils infiltration in great quantities, and occasional multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 2c). The histopathology stained with PAS revealed yeast-like cell structures (Fig. 2d). Microbiological study of a punch skin biopsy yielded dark colonies when cultured on SDA medium, morphologically identified as S. globosa, and confirmed by molecular identification, demonstrating a 100% match with the type-strain of S. globosa CBS120340 (GenBank accession number AM116908). Routine bacterial cultures and tests for acid-fast bacteria remained negative. In vitro antifungal susceptibility testing gave MIC values for ITR, TRB, VOR and AMB of 4μg/ml, 1μg/ml, 16μg/ml and 4μg/ml, respectively, while the MEC value for CAS was 16μg/ml. A low dosage of oral itraconazole 100mg q.d. was administrated, and local heat therapy was applied. At six-month follow-up, the plaques shrunk and became flat without any noticeable side effect.

DiscussionSporotrichosis is a subacute to chronic disease caused by members of the fungal genus Sporothrix, which are associated with soil and plant material with or without animal-vectored transmission. The prevalent clinical presentation is the lymphocutaneous form. In contrast to those cases occurring in other continents, large case series of sporotrichosis in China are dominated by fixed forms, followed by the lymphocutaneous form, while disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis is rare.11,12,23–29 Relative immune impairment or underlying metabolic diseases are not only important risk factors for deep infections with Sporothrix species, but may also enhance virulence of localized cases, as underlined by the fact that the two Chinese cases reported here occurred in patients with diabetes mellitus.2,13 Diabetes mellitus as a comorbidity for sporotrichosis has been reported before.16,19 However, most of these cases developed into disseminated, systemic or extracutaneous infections, especially in immunocompromised patients.1,4,7,9,22 Both our patients denied any history of trauma or a potentially contaminated injury to the upper extremity, while this is typical for the onset of a Sporothrix infection.

Several studies showed the existence of a relationship between geographical distribution and genotypes among species of the genus Sporothrix.15,28,30 With the exception of Africa and Australia, S. globosa has been reported globally, similar to its sibling S. schenckii.28 Previous epidemiological investigations proved that strains of S. globosa from Brazil, China, Japan, Spain, and United Kingdom had nearly identical genotypes. A yet unknown mechanism seems to be involved in the rapid dispersal of S. globosa.28 Given the large geographical distances between the localities where these genetically indistinguishable isolates have been found, airborne distribution seems to be the most plausible explanation. This was also the most likely scenario for other fungal pathogens.28 The absence of reported S. globosa infections and environmental isolates from Africa and Australia may be explained by sampling effects. Notably, S. globosa infections are derived from plant debris11,23,24 and this infection is classically known as ‘reed toxin’.23 Based on multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) and calmodulin gene sequence analysis, five Chinese environmental isolates of Sporothrix previously received as S. schenckii have been identified as S. globosa.15,26 This underlines the need for proper molecular characterization of fungal microorganisms and long-term availability of isolates for future research.8 Interestingly, cats have never been observed as sources of infection in endemic areas of S. globosa, while a large-scale ongoing and expanding outbreak of S. brasiliensis among humans and cats has been reported.21

Early diagnosis of Sporothrix schenkii s.l. infection is critical to prevent complications including septic arthritis, systemic infection, and death. Culture is the most sensitive method to make the diagnosis.5 Species identification of clinical isolates is essential to design reasonable regimens for antifungal treatment, epidemiological purposes, recognition of geographic distribution patterns, and the relevance between virulence and clinical patterns.

Recommended treatment for lymphocutaneous disease is oral itraconazole, 100–200mg q.d. for 3–6 months, with amphotericin B reserved for disseminated disease or severely immunocompromised patients.10,20 Fluconazole is only modestly effective for the treatment of sporotrichosis and should be considered as second-line therapy for the occasional patient who is unable to take itraconazole.9

A high suspicion for sporotrichosis and other atypical infectious agents in the setting of a lymphocutaneous syndrome is essential to prevent disease progression and repeated diagnostic interventions.

The authors thank Maria Francisca Colom for providing the Spanish translation of the abstract.