There are no epidemiological studies of Portuguese Public Hospitals in relation to infertility and its treatments.

ObjectivesWe characterized the infertile couple of a northern region of Portugal that uses a Public Hospital.

Materials and methodsA retrospective, epidemiological, observational and descriptive study was performed of couples attending infertile consultations at the Hospital Centre of St. John, Porto. A data-base was constructed and analyzed for the period 2005–2011.

ResultsOf the 1660 couples, 69% belonged to the district of Porto. The majority of the women were under 35 years of age (55%), were well-educated (74%), were eutrophic (55%), did not smoke (83%), presented high levels of alcohol consumption (56%) and primary infertility (74%), and the male factor was the main cause of infertility (44%). Of the 2245 treatment cycles performed, 60% were by intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI): 21% by in vitro fertilization, 9% by preimplantation genetic diagnosis, 9% by intra-uterine insemination and 1% by ovulation induction. The clinical pregnancy rates were similar to the European means (30%, 37%, 16%, 18% and 39%, respectively).

ConclusionsThe age of the ovary, smoking and obesity were not determinant factors of the infertility status. On the contrary, it is mandatory to increase the knowledge regarding the toxic effects of alcohol drinking. Primary infertility and male factor predominated, and as consequence the ICSI technique was the most used.

No existen estudios epidemiológicos de los hospitales públicos de Portugal en relación con la infertilidad y sus tratamientos.

ObjetivosCaracterizar las parejas infértiles en una determinada región del Norte de Portugal que acude a un Hospital Público.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio epidemiológico retrospectivo, observacional y descriptivo de las parejas que acudieron a la consulta de infertilidad en el Hospital de S. João, Porto entre 2005-2011, después de crearse una base de datos para este fin.

ResultadosDe las 1.660 parejas, el 69% pertenecían al distrito de Oporto. La mayoría tenía menos de 35 años (55%), un buen nivel de educación (74%), peso normal (55%), la ausencia de tabaquismo (83%), mayor consumo de alcohol (56%), la infertilidad primaria (74%) y factor masculino como la principal causa de infertilidad (44%). De 2.245 ciclos de tratamiento realizados, el 60% fueron por microinyección intracitoplasmática de espermatozoides (ICSI), el 21% por fertilización in vitro, el 9% por diagnóstico genético de pre-implantación, el 9% por inseminación intrauterina y el 1% por inducción de ovulación. Las tasas de embarazo clínico fueron similares a la media europea (30%, 37%, 16%, 18% y 39%, respectivamente).

ConclusiónSe observó que la edad del ovario, el consumo de tabaco y la obesidad no eran factores relevantes en la infertilidad. Por el contrario, los resultados evidencian la necesidad de una mayor concienciación de los efectos nocivos del consumo de alcohol. Predominaron la infertilidad primaria y el factor masculino por lo que en consecuencia el ICSI fue el método de tratamiento más utilizado.

Infertility is a disease of prominent importance in the actual western world and is defined as “a disease of the reproductive system defined by the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse”1 but it also includes women with inability to carry a pregnancy to childbirth. In the western world, the mean prevalence of infertility was estimated as 9% (3.5–16.7%) of the couples,2 and in Portugal to about 9–10%.3 Also in Portugal, only 43–48% of infertile women resort to medical consultations, 25% perform treatment cycles and 31% ignore the cause of their problem.3 Infertility may be primary if the woman never had a full term pregnancy or secondary when the woman had one or more previous pregnancies.4,5 It is supposed that infertility has not increased in the last decades but that infertility has gained much more public information and the availability of new techniques improved diagnosis. Additionally, nowadays couples decide more often to postpone their decision to conceive due to professional and economic reasons and this is associated with ovarian and testicle aging and more time of exposure to stress and social and ambient toxics.4,5

In our current society numerous ambiental, professional and habits have a strong impact on fertility. In this setting, one of the most important factors is aging of the reproductive tract, which is associated with lower fecundity rates and adverse reproductive outcomes; this includes the ovary, as after 35 years there is a significant decrease in oocyte number and quality,6–8 and the testes, as after 40 years there is a significant decrease in semen parameters.9,10 Infections of the male11 and female12 tracts are also, still today, an important component of infertility. Another cause of infertility is dependent on environmental and occupational toxics that may compromise the male13–16 and female17,18 reproductive functions.

Another critical aspect in our society today is the problem with western food intake and the associated obesity, with increased body mass index being associated with both female19,20 and male16,21–23 infertility. Alcohol abuse,16,24–26 cigarette smoking,16,27 drug addiction,16 high intensity exercise16 and medicines16 are also associated with lower fecundity rates and adverse reproductive outcomes. Finally, personality traits associated with depressive and anxiety disorders may also compromise female and male fertility.16,28

The objective of the present report was to characterize the infertile couple from the northeast Portuguese region that had infertility consultations at the Unit of Reproductive Medicine of the Hospital Centre of St. John, Porto, during the period 2005–2011.

Materials and methodsA patient database was developed for cases that had infertility consultations and treatments at the Unit of Reproductive Medicine of the Hospital Centre of St. John, Porto, Portugal. Data were used under written and informed patient consent according to the National Law of Assisted Medical Procreation (Law n.° 32/2006, of 26 July), and under the requirements of the National Council of Assisted Medical Procreation (CNPMA, 2008).

A retrospective, observational and descriptive study was performed from the patient database from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2011, with evaluation of 1660 cases. Data were collected from patients files between 2005 and 2007, while between 2008 and 2011 it were obtained from a computerized data base. We conducted a structured division of years as follows: 2005–2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011.

The hypotheses (questions) for the work regarding this population were:

- 1.

Do most couples look for health support when age begins to approach the limit or do instead look after two years without achieving a pregnancy?

- 2.

How many couples use health facilities outside their district of residence?

- 3.

Who are the municipalities in the district of Porto with over subscription to this service?

- 4.

Abnormal values of women body mass index can change the odds of conception?

- 5.

Are there couples to seek help without changing their habits, even though they may affect their problem?

- 6.

Is primary infertility the most common type of infertility?

- 7.

What is the factor of infertility with a higher prevalence?

- 8.

What percentage of couples is still unaware of the cause of their infertility?

- 9.

The number of cycles performed per year is increasing?

- 10.

The proportion of couples that can effectively carry out a pregnancy using only the induction of ovulation is reduced?

- 11.

What kind of treatment is the most suited to each factor of infertility (male, female, both)?

- 12.

What percentage of couples achieved a pregnancy?

The variables that were collected throughout the study were:

- 1.

Demographic data: age at the beginning of treatment, district and municipalities of residence, marital status, occupation, height, weight, body mass index, smoking and ethyl habits. Considering body mass index, smoking and ethyl habits these are exclusively presented for women, as patient files did not incorporated male data.

- 2.

Assessment data: type of infertility, cause of infertility (male, female, mixed factors), type of treatment cycles (ovulation induction, intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, preimplantation genetic diagnosis) and cycles outcomes (clinical pregnancy: yes or no).

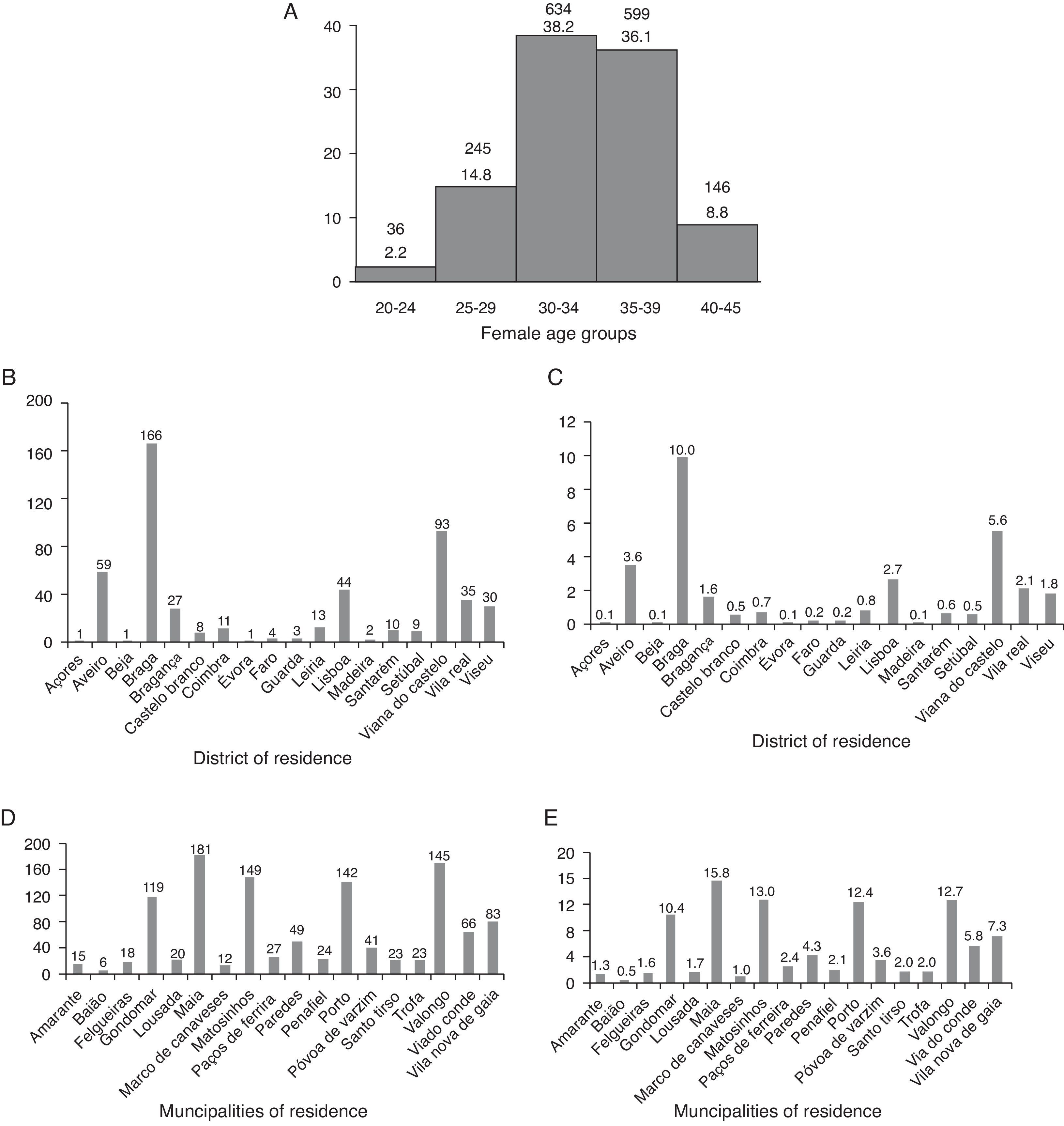

Only those infertile couples who are officially married or live together for a minimum of two years can be treated in the Public health system according to the National Law of Assisted Medical Procreation. For this motive all couples (1660) belonged to this marital status. Regarding female age groups the majority (55.1%; 915/1660) had less than 35 years and 74.3% (1233/1660) belonged to the group of 30–39 years (Fig. 1A). Concerning the district of residence, Porto displayed the higher percentage (68.9%; 1143/1660) whereas 31.1% (517/1660) came from other zones. Of the latter, the majority came from Braga and Viana do Castelo. Except for Porto, only Viana do Castelo belonged to the reference Hospital (Fig. 1B and C). Analysis of the municipalities in the district of Porto revealed that most of the couples came from Maia, followed by Matosinhos, Valongo, Porto and Gondomar. Only Maia, Matosinhos, Porto, Póvoa de Varzim and Vila do Conde belonged to the reference Hospital (50.7%; 579/1143) (Fig. 1D and E).

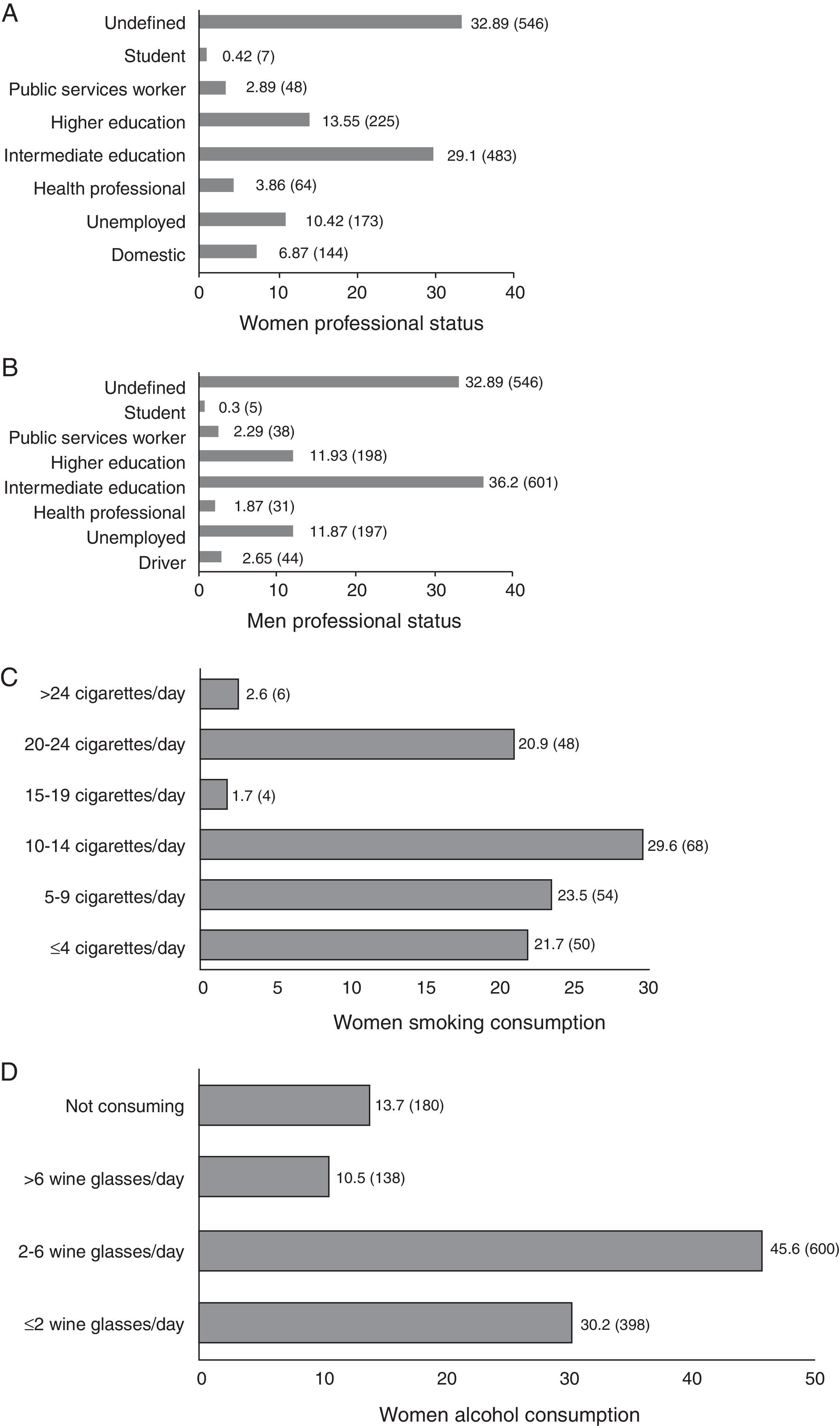

In relation to the professional status, the majority of the women (74.2%; 827/1114) and men (78.4%; 873/114) had evident intermediate or higher education levels (Fig. 2A and B). Three risks for infertility were evaluated regarding weight and habits. Regarding the body mass index, the majority 54.8% (888/1619) was eutrofic (BMI: 18.5–24.99), 27.3% (442/1619) had overweight (BMI: 25–29.99), 14.7% (238/1619) were obese (BMI: ≥30) and 3.2% (51/1619) presented underweight (BMI: <18.5). Relatively to the smoking habits the majority of the women (82.5%; 1086/1316) were no smokers and 17.5% (230/1316) were smokers. In total, 7.9% consumed less than ten cigarettes and 9.6% smoked more than ten cigarettes per day, whereas in relation to smokers these rates were 45.2% and 54.8% respectively (Fig. 2C). On the contrary, in relation to alcohol consumption, 56.1% (738/1316) of the women consumed more than two wine glasses per day, whereas 43.9% (578/1316) did nor consume or consumed less than 2 wine glasses per day (Fig. 2D).

(A) Frequency and percentage of female professional status. (B) Frequency and percentage of male professional status. (C) Frequency and percentage of female smoking habits. (D) Frequency and percentage of female alcohol consumption. Undefined: without data in files; student: high school students; public services workers: 12th grade; health professional: physicians, nurses, physiatrists, university professors; unemployed: without data in files; domestic: less than 9th grade.

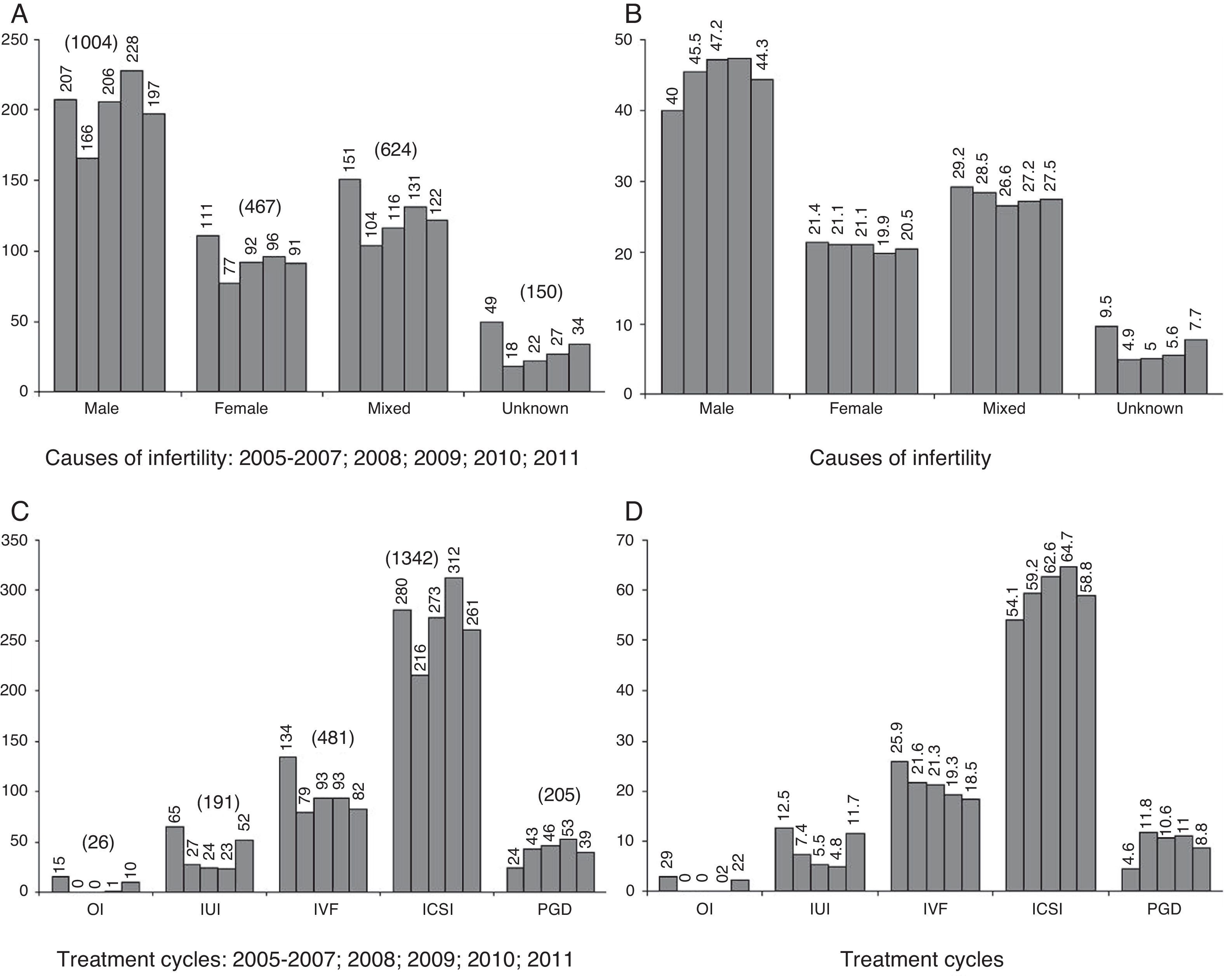

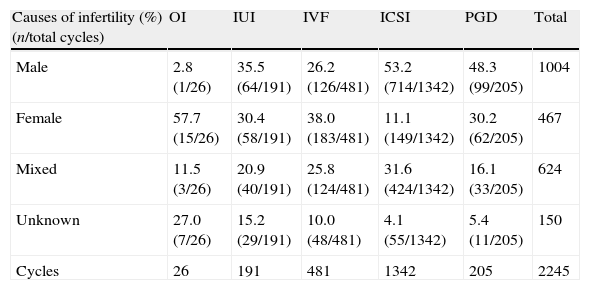

Of the 1660 cases, 74% (1228) of the couples presented primary infertility and 26% (432) had secondary infertility. The main infertility cause was of male origin (44.3%; 736), followed by mixed causes (28%; 464), female causes (20.5%; 341) and unknown origin (7.2%; 119). There was a total of 2245 treatment cycles, 518 in 2005–2007, 365 in 2008, 436 in 2009, 482 in 2010 and 444 in 2011. The evolution along the studied years regarding the causes of infertility per cycle revealed that the rates remained relatively consistent, for male (mean of 44.7%) mixed (mean of 27.8%), female (mean of 20.8%) and unknown (mean of 6.7%) causes (Fig. 3A and B). Regarding the frequency of the treatment technique used per each cause of infertility, the main cause in ovulation induction (OI) cycles was female, in intra-uterine insemination (IUI) cycles were male, female and mixed, in in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles were female, male and mixed, and in intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and in preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) cycles was male (Table 1). Different tendencies were observed when causes were analyzed in pregnant women (657 clinical pregnancies), with OI cycles having a predominance of female and unknown causes, in IUI cycles of male and female causes, in IVF cycles of female causes, in ICSI cycles causes remained similar (male) and PGD cycles had a predominance of female causes (Table 1).

Causes of infertility per type of treatment and in pregnant women.

| Causes of infertility (%) (n/total cycles) | OI | IUI | IVF | ICSI | PGD | Total |

| Male | 2.8 (1/26) | 35.5 (64/191) | 26.2 (126/481) | 53.2 (714/1342) | 48.3 (99/205) | 1004 |

| Female | 57.7 (15/26) | 30.4 (58/191) | 38.0 (183/481) | 11.1 (149/1342) | 30.2 (62/205) | 467 |

| Mixed | 11.5 (3/26) | 20.9 (40/191) | 25.8 (124/481) | 31.6 (424/1342) | 16.1 (33/205) | 624 |

| Unknown | 27.0 (7/26) | 15.2 (29/191) | 10.0 (48/481) | 4.1 (55/1342) | 5.4 (11/205) | 150 |

| Cycles | 26 | 191 | 481 | 1342 | 205 | 2245 |

| Causes of infertility in pregnant women (%) (n CP/total CP) | OI | IUI | IVF | ICSI | PGD | Total |

| Male | 0.0 (0/10) | 37.1 (13/35) | 24.6 (44/179) | 57.4 (230/401) | 31.2 (10/32) | 297 |

| Female | 40.0 (4/10) | 31.4 (11/35) | 40.8 (73/179) | 12.5 (50/401) | 50.0 (16/32) | 154 |

| Mixed | 20.0 (2/10) | 14.3 (5/35) | 24.0 (43/179) | 25.9 (104/401) | 18.8 (6/32) | 160 |

| Unknown | 40.0 (4/10) | 17.1 (6/35) | 10.6 (18/179) | 4.2 (17/401) | 0.0 (0/32) | 46 |

| CP | 10 | 35 | 179 | 401 | 32 | 657 |

OI: ovulation induction; IUI: intrauterine insemination; IVF: in vitro fertilization; ICSI: intracytoplasmic sperm injection; PGD: preimplantation genetic diagnosis; CP: clinical pregnancy.

In relation to the number of cycles (2245) realized along the studied years there was a predominance of ICSI cycles (59.8%), followed by IVF cycles (21.4%), PGD cycles (9.1%), IUI cycles (8.5%) and OI cycles (1.2%). Along the studied period, the frequency of ICSI and PGD increased; there was a tendency to a recent increase in OI and IUI treatment cycles after a general decrease observed between 2008 and 2010; and a sustained decrease in IVF cycles (Fig. 3C and D).

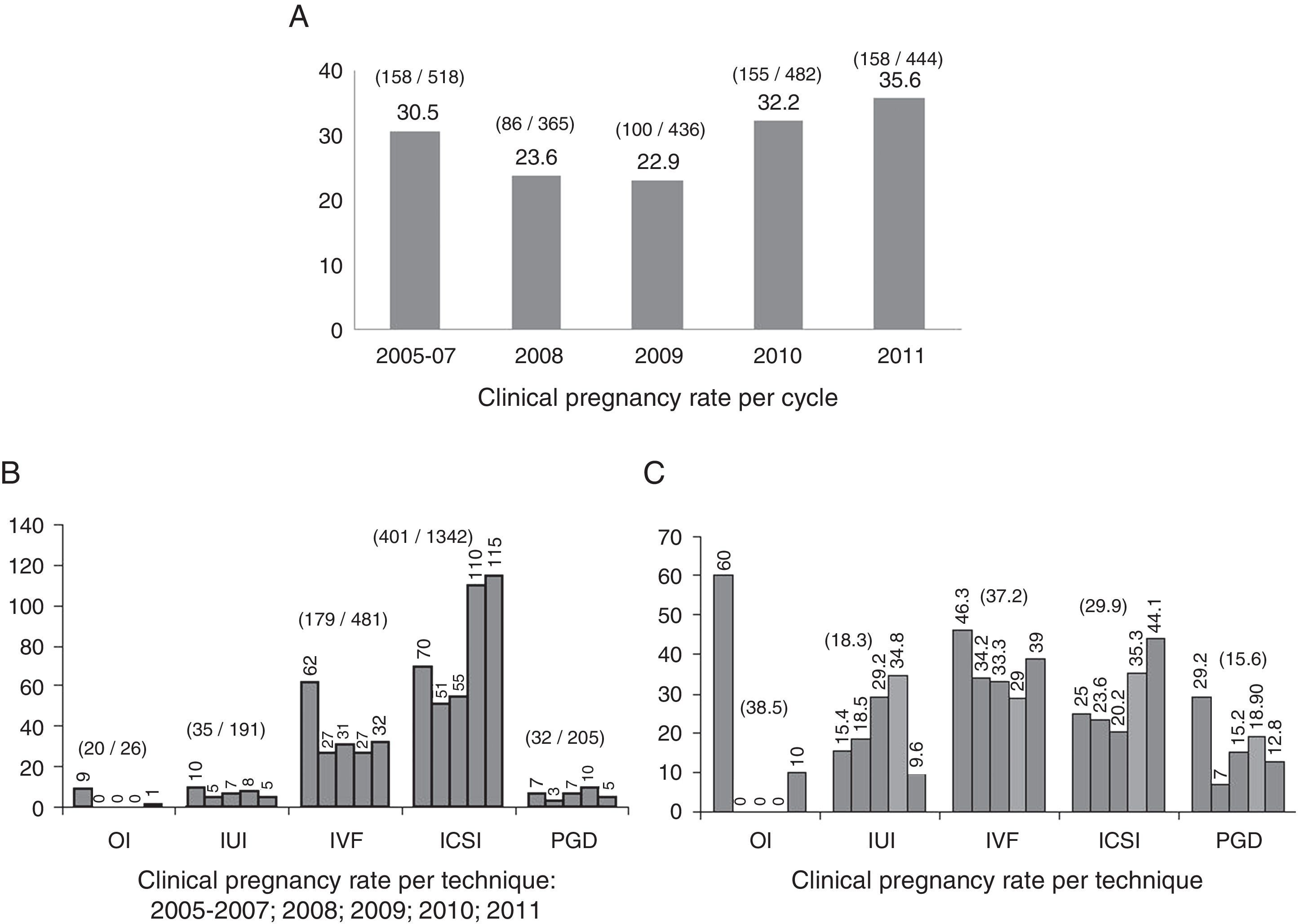

The rates of clinical pregnancy have increased along the studied years, from 30.5 to 35.6, with a slight decrease in 2008 and 2009 (Fig. 4A). Of the 2245 treatment cycles (with 657 clinical pregnancies), the rates of clinical pregnancy were 38.5 for OI, 18.3 for IUI, 37.2 for IVF, 29.9 for ICSI and 15.6 for PGD (Fig. 4B and C).

DiscussionIn Portugal there are 10 Public and 17 Private Units of Reproductive Medicine that perform assisted reproduction treatments. Not all have all techniques disponible and thus some specific pathologies are treated with collaborations. According to reports of the National Council of Assisted Medical Procreation in total during 2011 there were 2049 IUI cycles (1027 in Public centres, 1022 in Private centres), 1830 IVF cycles (970 in Public centres, 860 in Private centres), 3873 ICSI cycles (1784 in Public centres, 2089 in Private centres) and 69 PGD cycles (46 in Public centres, 23 in Private centres). In the National registries there is no information regarding OI. Thus, in 2011, in Portugal, there were a total of 7752 cycles, with a representation of IVF (23.6%), ICSI (50%) and IUI (26.4%). In Public centres these figures were 3781 cycles of IVF (25.7%), ICSI (47.2%) and IUI (27.2%), and in Private centres there were 3971 cycles with IVF (21.7%), ICSI (52.6%) and IUI (25.7%). Our present report refers to a Public centre with numbers regarding the period of 2005–2011.

Analysis of the results indicated that the majority of the infertile couples (74%) seek support from health facilities when women are between 30 and 39 years. In the past, women were educated to marry and raise a family as a priority, but recently started to include other life goals such as career success and financial independence so that pregnancy is postponed. Consequently and due to ovary aging the older age of conception naturally reduces the possibility and chances of pregnancy.7,8

Of the 1660 infertile couples, it was observed that 69% belonged to their area of residence in Porto and that 31% moved outside this region. Of these, the vast majority belonged to areas outside of the centre of reference, which is explained by matching the cases that started treatment before the official change of reference regions.

About 74% (females) and 78% (males) of the couples had enough levels of education that allowed access to information about infertility more easily. These values mean that most of the couples do have adequate levels of schooling to better understand their problem, and that the actual large diffusion of information and the loss of the stigmata linked to infertility is allowing with the brevity required the access to the RMA centres. Interestingly, higher levels of infertility were observed among women with higher levels of education, with the cultural level having been involved with the decision to become pregnant later.29 These findings are different from the values found in a Portuguese epidemiological study that showed that the majority of infertile women have four or less years of education.3

The observation that most of the infertile women (83%) did not smoke and that of those who smoke 45% consumed less than 10 cigarettes per day clearly indicates that women are aware of the pernicious effects of smoke. Cigarette smoke contains several toxics that impact over oocyte quality, ovulation, embryo transport over the Fallopian tube, implantation and fetal growth.16,27 Similar values were found in a Portuguese epidemiological study.3 However 56% of the women consumed more than two wine glasses per day. The negative impact on fertility is the same reported to cigarette smoke.24,29 This finding suggests that women need to find a recreational consumption that instead of smoking is being directed to alcohol consumption. These findings contrast with the values found in a Portuguese epidemiological study that indicated that the majority of infertile women do not consume alcoholic beverages.3

Obesity is a most actual problem of our society and is related to ovulation disturbances, difficulties in embryo implantation and complicated gestations.19,20 The present findings were rewarding as 55% of the studied women were eutrophic, and considering that overweight do not impact too much over fecundity, then 82% of the women had a compatible weight to reproduction. Similar values were found in a Portuguese epidemiological study.3

Most of the studied couples (74%) presented primary infertility. The male factor was the most representative (44%) and together with mixed factors this raises to 72% the factors were the male factor was present. It is supposed that this high level of male factor is due to a recent more accurate diagnostic of male problems.30,31 The rate of unknown causes was relatively low (7%) in relation to published reports.32,33 and this can be explained by a more exhaustive diagnostic search in the studied population.

As a consequence there were more ICSI cycles (60%). In these the male factor (53%) was obviously predominant, attaining 85% with mixed causes, with the same being observed in pregnant women from ICSI cycles (57% and 83%). The clinical pregnancy rate was 30%, which was similar to that reported from Europe and Portugal (29%).34 Regarding IVF the causes of infertility were similarly distributed, female (predominant), male and mixed, with a predominance of the first two (64%), with the same being observed in pregnant women from IVF cycles (65%). The rate of clinical pregnancy was 37%, which was slightly superior in relation to the European mean (29%) but similar to the Portuguese mean (36%).34 Concerning PGD, there was predominance of the male factor, but in pregnant women from PGD cycles the female factor predominated. The clinical pregnancy rate was 16%, which was lower than the European mean (25%).34,35

For IUI as for IVF the causes of infertility were similarly distributed, male, female and mixed, with a predominance of the first two (66%), and in pregnant women from IUI cycles there was a predominance of male and female factors (69%). The rate of clinical pregnancy was 18% and although the European (8%) and Portuguese (10%) results were only given per delivery,34 it is possible that the present results will be similar.36 The percentage of cycles of IUI (8.5%) in the present center was low regarding the Portuguese report of 27.2% of IUI cycles in 2011 in Public centres. Although not completely comparable as our report is during the period of 2005 to 2001, it may reflect the high variability of patients in each center, with a predominance of ICSI cycles in our center (59.8%). Notwithstanding, the percentage of IUI cycles in 2011 increased to 11.7% and that of IVF decreased to 18.5%, which is similar to the proportion observed in Portuguese data (25.7% IVF and 27.2% IUI). This may reflect the fact that patients are more aware of the infertility problems and seek for help much more frequently and earlier in their problems nowadays. Additionally, due to the present severe economic restrictions it is also possible that techniques are more strictly selected.

The IO procedure was mainly applied for female infertility causes (58%), but in pregnant women from OI cycles there was an equal predominance of female and unknown factors (80%). The pregnancy rate obtained was 39%, which is similar to that reported,37 but it can be overestimated due to the low number of patients.

In conclusion, of the 1660 infertile couples analyzed during 2005–2011 we observed that the ovary age was not a relevant factor as 55% of the women had less than 35 years. The same could be observed regarding cigarette smoking and weight, as the large majority were non-smokers and not obese. A society problem was however found regarding alcohol beverages as the majority of the women drink to excess. Primary infertility was the main type of infertility found, altogether with infertility due to male causes, and consequently ICSI was the main technique used. The rates of clinical pregnancy found were similar to the European and Portuguese databases.

Conflict of interestThe Authors declare to have no conflict of interest.

Ethical responsibilitiesConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Protection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

UMIB is funded by National Funds through FCT-Foundation for Science and Technology, under the Pest-OE/SAU/UI0215/2014.