Prostate cancer is the second most frequently diagnosed cancer in men. The initial diagnosis is made in increasingly younger patients, so it seems to be essential to guarantee optimal functional results. We carried out a systematic search to define the functional results of each of the therapeutic options for localized prostate cancer. Radical prostatectomy generates a greater negative effect on urinary continence and erectile function compared to active surveillance and radiotherapy. Robotic surgery seems to offer better functional results, especially at the level of erectile function. Urinary and bowel symptoms are more pronounced after radiotherapy compared to other options. Patients must be warned of the possible functional results prior to choice of treatment.

El cáncer de próstata es el segundo cáncer que se diagnostica con mayor frecuencia en varones. El diagnóstico inicial se establece en pacientes cada vez más jóvenes, por lo que parece que es fundamental para garantizar resultados funcionales óptimos. Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática para definir los resultados funcionales de cada una de las opciones terapéuticas para el cáncer de próstata localizado. La prostatectomía radical genera mayor efecto negativo sobre la continencia urinaria y la función eréctil en comparación con la vigilancia activa y la radioterapia. Parece que la cirugía robótica ofrece mejores resultados funcionales, sobre todo respecto a la función eréctil. Los síntomas urinarios e intestinales son más pronunciados después de la radioterapia en comparación con otras opciones. Se debe advertir a los pacientes de los posibles resultados funcionales antes de elegir el tratamiento.

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most diagnosed cancer in men, constituting 15% of all diagnosed tumors. PCa has a prevalence of 1.1 million affected patients in 2012 and is estimated to affect 1.7 million in 2030.1 In addition, it is the most frequent cause of morbidity and the second most frequent cause of cancer-related mortality in men.2 On many occasions, the diagnosis is made in healthy and young patients, that is, younger than 65 years of age, and with a life expectancy of more than 10 years, who seek definitive treatment without losing their quality of life. In general, the average life expectancy after diagnosis is 13.8 years, with a cancer-specific survival of 95% at 5 years and 90% at 10 years.3 The exponential use of PSA as a “screening marker” and the more selective indication for prostate biopsies have led to the more and more frequent diagnosis of PCa in early stages. This fact, together with the increase in overall life expectancy, make it increasingly important to take into account the quality of life after treatment.4 Quality of life is closely linked to functional results after initial treatment, mainly urinary incontinence (UI) and erectile dysfunction (ED).

Localized PCa is defined as that which does not exceed stage T2, meaning that it does not extend beyond the prostatic capsule. In addition, it can be stratified into risk groups according to the D’Amico classification system, with low risk tumors (PSA<10, GS<7 or cT2a), intermediate risk tumors (PSA 10–20, GS 7 or cT2b) or high risk tumors (PSA>20, GS>7 or cT2c).5 The main treatment options for this type of patients are active surveillance (AS), radical prostatectomy (RP), radiotherapy (EBRT), brachytherapy (BT) and ablative or focal techniques such as HIFU and cryotherapy within the context of clinical trials, all with a grade A recommendation.5 In general terms, none of the options demonstrates superiority in the control of the cancer, and the choice of each of them depends on the patient's clinical characteristics, their life expectancy, their health status, patients’ access to each option, their preferences and the profile of the possible complications that could occur.5

The objective of this review is to define, in an updated manner and with the greatest possible scientific evidence, the incidence and characteristics of the main functional results of each of the therapeutic options of localized PCa with curative intentions, understanding as functional results not only UI and ED, but also obstructive and irritative voiding symptoms and intestinal symptoms depending on the different treatments.

Review methodA narrative review was carried out summarizing the data published to date on the functional results of the different treatment options for localized PCa. For this, a systematic search was made of original studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses published before January 2017 using MEDLINE-PubMed with the following search terms: “radical prostatectomy”, “active surveillance”, “radiotherapy”, “brachytherapy”, “HIFU”, “cryotherapy”, “ablative therapies” and “functional outcomes”. Studies were included where the treatment in question was used exclusively as first line, preferably in randomized clinical trials, prospective and retrospective comparative series and individual series, in this order. Whenever possible, except in the case of a very relevant study, data from studies that associated androgen deprivation to one of the treatment arms were not included. In relation to sexual function, the evaluation was limited to erectile dysfunction, avoiding the inclusion of other elements of sexual function such as ejaculation, orgasm, and desire, to keep the review from becoming too complex and extensive. The main author compiled the bibliography, established a structure and prepared a draft. The definitive text was defined as a narrative review and was critically reviewed by all co-authors before its submission and final acceptance.

Active surveillanceActive surveillance (AS) consists of the progressive follow-up of the patient with PCa by means of PSA controls and serial prostate biopsies. The patients who are candidates to start an AS protocol are those with a life expectancy of more than 10 years and with low-risk PCa,5 as the mortality associated with low-risk tumors could be as low as 7% in fifteen years of follow-up.5 The conceptual basis of AS is to avoid adverse effects related to active treatment. Higher levels of anxiety have not been observed in patients undergoing AS. Disease progression data are what usually force the suspension of the follow-up protocol,6 and thus, approximately 60% are treated with curative intention at 10 years, or 50% if very low risk inclusion criteria were used.7

Despite trying to minimize the morbidity caused by active treatment, AS patients have also shown to suffer from a certain degree of sexual dysfunction. In fact, although it is true that these patients are more sexually active than those undergoing radical therapy, 44–51% of them suffer from some difficulty in reaching or maintaining an erection compared to 81–85% of those treated.8,9 Even so, this deterioration, which is significant compared to patients without PCa, has little clinical relevance, is difficult to distinguish from the natural aging process, and may be related to the present comorbidities and PSA kinetics, and not to the state of anxiety found in these patients.10,11

On the other hand, although the multiple prostate biopsies characteristic of AS may cause inflammatory processes in the prostate,12 no association has been demonstrated between the number of prostatic biopsies and the worsening of erectile function, or the progression of symptoms of the lower urogenital and digestive tracts over the long term during AS.11 These soft-tissue processes could increase complexity when needing to establish surgical planes during surgery and this, in turn, could have an impact on the subsequent functional results, however, referring to the ED, although there may be a negative relationship if surgery is performed in the first 6 months,12 this difference was not observed after the first year of follow-up,10,13–15 and regarding the UI, the effect proved to be null.10,12–14

Radical prostatectomyThe functional results of radical prostate surgery or radical prostatectomy (PR), especially regarding UI and ED, are the factors that most deteriorate the overall well-being of patients undergoing surgery. There are three radical prostatectomy techniques: the open or retropubic approach (ORP), the laparoscopic approach (LRP) and the robot-assisted approach (RARP). Regardless of the technique used, the preservation of the neurovascular bundles is a key factor for the recovery not only of the erectile function, but also for the recovery of continence, as the pelvic plexus provides autonomic innervation to the external sphincter; recovery is faster when preservation is bilateral.16

Robotic radical prostatectomy. Currently, the surgical technique that seems to show better functional results is the RARP.17,18 This approach offers a series of advantages over other surgical techniques including the ease of making precise and meticulous movements while offering freedom in surgical movement (7 degrees of movement), reduction of any shaking of the surgeon's hands, optical magnification, the three-dimensional vision and the ergonomics of the surgical console. There are no clear recommendations about the patient profile that could benefit more from one approach or another.5 That said, it is true that those patients who undergo robotic surgery tend to be younger patients with a lower rate of comorbidities, where the robotic approach makes more sense in order to preserve the previous urinary and sexual functionality. This can infer an obvious selection bias when comparing the functional results of the different approaches.

Simple series of RARP provide excellent results in the recovery of urinary continence and erectile function. Considering continence as the absence of use of liners or pads, or their use for any potential leaks, recovery rates are 65% at 3 months, 88% (79–97%) at 6 months, 91% (89–92%) at 12 months and 95% at 24–36 months.17 As for the preservation of erectile function, the results are equally good. The rates of potent patients after RARP with bilateral preservation of neurovascular bundles are 56% (32–68%) at 3 months, 69% (50–86%) at 6 months, 74% (62–90%) at 12 months and 82% (69–94%) at 24 months.18 Nonetheless, there are many factors that can influence the variability of recovery results of erectile function such as patient age, preoperative erectile function, comorbidity index, quality of nerve preservation during surgery, the definition of the concept of recovery of erectile function and the follow-up or lack thereof of a penile rehabilitation protocol after surgery.

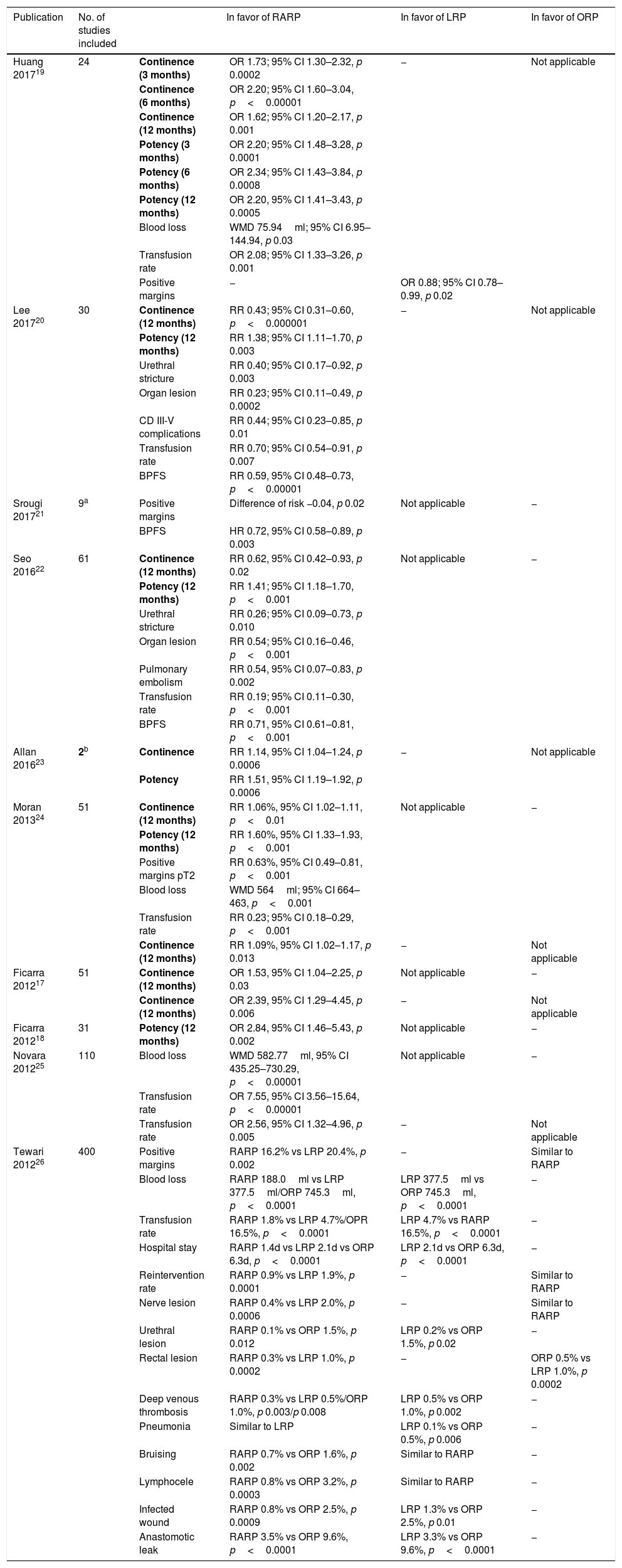

Systematic reviews. An attempt has been made to combine the multiple published comparative studies into two systematic reviews and meta-analysis.17,18 In relation to the recovery of urinary continence, if RARP is compared with LRP, recovery occurs in 64–92% of the patients at 6 months, and in 82–100% at 12 months with LRP, compared to 40–93% at 6 months and 93–100% at 12 months with RARP, with the results being favorable with the robotic technique (RR LRP 9.6% vs. RR RARP 5%, OR 2.39 (95% CI 1.29–4.45, p 0.006)). Comparing RARP with ORP, recovery occurs in 54–84% of patients at 6 months, in 80–97% at 12 months and at 130–160 days after ORP, compared to 40–97% at 6 months, 89–100% at 12 months and at 44–110 days after RARP, the results being favorable to the robotic technique (RR ORP 11.3% vs. RR RARP 7.5%, OR 1.53 (95% CI 1.04–2.25, p 0.03).17 Regarding the recovery of sexual function, comparing RARP and LRP, at 12 months after the intervention, 32–78% recover with LRP versus 55–81% with RARP, with no statistically significant difference between both techniques (RR LRP 55.6% vs. RR RRP 39.8%, OR 1.89 (95% CI 0.70–5.05, p 0.21).) The cumulative analysis between the PRL and the PRAR offers similar results, although there is a slight favorable trend for the PRAR. In the comparison between PRA and PRAR, the recovery of function at 12 months is 26–63% in PRA compared to 55–81% in PRAR; the statistically significant difference in meta-analysis is in favor of PRAR (RR PRA 47.8% vs. RR PRAR 24.2%, OR 2.84 (95% CI 1.48–5.43, p 0.002)).18 These 2 systematic reviews may be the of highest quality of that published, but there are also others that have been published since then that have showed similar results, that is, in favor of robotic surgery for early functional recovery and intra-operatory results17–26 (Table 1).

Systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Cumulative analysis of comparative studies between techniques.

| Publication | No. of studies included | In favor of RARP | In favor of LRP | In favor of ORP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang 201719 | 24 | Continence (3 months) | OR 1.73; 95% CI 1.30–2.32, p 0.0002 | − | Not applicable |

| Continence (6 months) | OR 2.20; 95% CI 1.60–3.04, p<0.00001 | ||||

| Continence (12 months) | OR 1.62; 95% CI 1.20–2.17, p 0.001 | ||||

| Potency (3 months) | OR 2.20; 95% CI 1.48–3.28, p 0.0001 | ||||

| Potency (6 months) | OR 2.34; 95% CI 1.43–3.84, p 0.0008 | ||||

| Potency (12 months) | OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.41–3.43, p 0.0005 | ||||

| Blood loss | WMD 75.94ml; 95% CI 6.95–144.94, p 0.03 | ||||

| Transfusion rate | OR 2.08; 95% CI 1.33–3.26, p 0.001 | ||||

| Positive margins | − | OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.78–0.99, p 0.02 | |||

| Lee 201720 | 30 | Continence (12 months) | RR 0.43; 95% CI 0.31–0.60, p<0.000001 | − | Not applicable |

| Potency (12 months) | RR 1.38; 95% CI 1.11–1.70, p 0.003 | ||||

| Urethral stricture | RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.17–0.92, p 0.003 | ||||

| Organ lesion | RR 0.23; 95% CI 0.11–0.49, p 0.0002 | ||||

| CD III-V complications | RR 0.44; 95% CI 0.23–0.85, p 0.01 | ||||

| Transfusion rate | RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.54–0.91, p 0.007 | ||||

| BPFS | RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.48–0.73, p<0.00001 | ||||

| Srougi 201721 | 9a | Positive margins | Difference of risk −0.04, p 0.02 | Not applicable | − |

| BPFS | HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.58–0.89, p 0.003 | ||||

| Seo 201622 | 61 | Continence (12 months) | RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.42–0.93, p 0.02 | Not applicable | − |

| Potency (12 months) | RR 1.41; 95% CI 1.18–1.70, p<0.001 | ||||

| Urethral stricture | RR 0.26; 95% CI 0.09–0.73, p 0.010 | ||||

| Organ lesion | RR 0.54; 95% CI 0.16–0.46, p<0.001 | ||||

| Pulmonary embolism | RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.07–0.83, p 0.002 | ||||

| Transfusion rate | RR 0.19; 95% CI 0.11–0.30, p<0.001 | ||||

| BPFS | RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.61–0.81, p<0.001 | ||||

| Allan 201623 | 2b | Continence | RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.04–1.24, p 0.0006 | − | Not applicable |

| Potency | RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.19–1.92, p 0.0006 | ||||

| Moran 201324 | 51 | Continence (12 months) | RR 1.06%, 95% CI 1.02–1.11, p<0.01 | Not applicable | − |

| Potency (12 months) | RR 1.60%, 95% CI 1.33–1.93, p<0.001 | ||||

| Positive margins pT2 | RR 0.63%, 95% CI 0.49–0.81, p<0.001 | ||||

| Blood loss | WMD 564ml; 95% CI 664–463, p<0.001 | ||||

| Transfusion rate | RR 0.23; 95% CI 0.18–0.29, p<0.001 | ||||

| Continence (12 months) | RR 1.09%, 95% CI 1.02–1.17, p 0.013 | − | Not applicable | ||

| Ficarra 201217 | 51 | Continence (12 months) | OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.04–2.25, p 0.03 | Not applicable | − |

| Continence (12 months) | OR 2.39, 95% CI 1.29–4.45, p 0.006 | − | Not applicable | ||

| Ficarra 201218 | 31 | Potency (12 months) | OR 2.84, 95% CI 1.46–5.43, p 0.002 | Not applicable | − |

| Novara 201225 | 110 | Blood loss | WMD 582.77ml, 95% CI 435.25–730.29, p<0.00001 | Not applicable | − |

| Transfusion rate | OR 7.55, 95% CI 3.56–15.64, p<0.00001 | ||||

| Transfusion rate | OR 2.56, 95% CI 1.32–4.96, p 0.005 | − | Not applicable | ||

| Tewari 201226 | 400 | Positive margins | RARP 16.2% vs LRP 20.4%, p 0.002 | − | Similar to RARP |

| Blood loss | RARP 188.0ml vs LRP 377.5ml/ORP 745.3ml, p<0.0001 | LRP 377.5ml vs ORP 745.3ml, p<0.0001 | − | ||

| Transfusion rate | RARP 1.8% vs LRP 4.7%/OPR 16.5%, p<0.0001 | LRP 4.7% vs RARP 16.5%, p<0.0001 | − | ||

| Hospital stay | RARP 1.4d vs LRP 2.1d vs ORP 6.3d, p<0.0001 | LRP 2.1d vs ORP 6.3d, p<0.0001 | − | ||

| Reintervention rate | RARP 0.9% vs LRP 1.9%, p 0.0001 | − | Similar to RARP | ||

| Nerve lesion | RARP 0.4% vs LRP 2.0%, p 0.0006 | − | Similar to RARP | ||

| Urethral lesion | RARP 0.1% vs ORP 1.5%, p 0.012 | LRP 0.2% vs ORP 1.5%, p 0.02 | − | ||

| Rectal lesion | RARP 0.3% vs LRP 1.0%, p 0.0002 | − | ORP 0.5% vs LRP 1.0%, p 0.0002 | ||

| Deep venous thrombosis | RARP 0.3% vs LRP 0.5%/ORP 1.0%, p 0.003/p 0.008 | LRP 0.5% vs ORP 1.0%, p 0.002 | − | ||

| Pneumonia | Similar to LRP | LRP 0.1% vs ORP 0.5%, p 0.006 | − | ||

| Bruising | RARP 0.7% vs ORP 1.6%, p 0.002 | Similar to RARP | − | ||

| Lymphocele | RARP 0.8% vs ORP 3.2%, p 0.0003 | Similar to RARP | − | ||

| Infected wound | RARP 0.8% vs ORP 2.5%, p 0.0009 | LRP 1.3% vs ORP 2.5%, p 0.01 | − | ||

| Anastomotic leak | RARP 3.5% vs ORP 9.6%, p<0.0001 | LRP 3.3% vs ORP 9.6%, p<0.0001 | − | ||

2 single randomized clinical trials n 232 (level of evidence 1). In bold, functional results (UI, ED). RARP – radical assisted radical prostatectomy, LRP – laparoscopic radical prostatectomy, ORP – open radical prostatectomy, BPFS – biochemical progression-free survival, CD – Clavien-Dindo, WMD – weighted mean difference, OR – odds ratio, RR – relative risk, CI – confidence interval.

Despite the good results in terms of continence and recovery of erectile function in favor of RARP, these reviews should be interpreted with caution. The evidence that is extracted is still low due to the methodological quality, with a majority of series of comparative cases including retrospective and non-randomized retrospective cases, and the inherent selection bias. In general, surgeon skill was not evaluated, with the surgeon's experience being a more powerful predictor than the surgical technique itself. In addition, the variability in the definition of UI and ED, with the irregular use of validated questionnaires, and the variability in the follow-up of rehabilitation protocols, also limit the interpretation of the results of these meta-analyses.

On the other hand, the systematic reviews performed comparing the 3 techniques with other objectives did not show superiority of any approach in oncological terms.27 They did, however, show superiority regarding the perioperative results and presence of postoperative complications, where RARP required a lower rate of blood transfusions compared to ORP and LRP.25

Randomized clinical trials. To date, only two studies have been published that provide a 1b level of evidence, that is, as prospective and randomized studies.28,29 In both, the LRP is compared to the RARP with nerve preservation, performed in a single center and by the same experienced surgeon. In the first, for patients undergoing RARP, the percentage of continence was higher at all cut-off points, and the percentage of potent patients was higher only at 12 months.28 In the second, no statistically significant differences were found in the continence between groups at any of the cut-off points, however, a statistically significant superiority of RARP was observed in terms of potency from the first month after surgery. It is true, however, that the mentioned studies do not have any real applicability as the results are limited to a single surgeon.29 Recently another phase III controlled clinical trial has been published, which is the first to compare ORP with RARP. In the short term (12 months) no differences were found in the functional results, however, RARP provided better intra- and post-operative results, such as the reduction of surgical time, blood loss, postoperative pain and hospital stay. The extensive experience of the two surgeons involved, the fact that the study was not blind and the lack of long-term follow-up, limit the conclusions of this study.30

Despite the relative low level of evidence in general, the results reflect that RARP offers better functional results, especially in terms of recovery of erectile function. Its high cost, both in acquisition and maintenance, must be justified by a clear superiority over other techniques.31 Therefore, more studies are needed that provide greater evidence to impose RARP as a “gold-standard” for the surgical treatment of PCa due to its clear superiority over other techniques.

Radiotherapy – brachytherapyThe data on functional results after radiotherapy (EBRT) and brachytherapy (BT) in patients with localized PCa are heterogeneous and vary according to the type of treatment used.32

Both irritative and obstructive urinary symptoms are evaluated by degrees of toxicity, including early and late onset. The incidence of moderate grade 2 genitourinary toxicity (frequency, dysuria, hematuria) is 20% at doses of 81Gy versus 12% at lower doses.33 In the EBRT modality with a three-dimensional configuration, a higher dose leads to a higher number of complications. The percentage of late onset toxicities is similar after 3 years of follow-up, regardless of the initial dose.32 In the modality of radiotherapy with modulated intensity (IMRT), there is greater late onset toxicity at 10 years with higher doses.32 However, in BT, moderate initial toxicity is generated (increase in baseline IPSS by 5.6 points between the first and sixth month) returning to normal in mid-term follow-up (baseline IPSS increase of 0.41 points between the fourth and fifth year of follow-up).32

The etiology of ED in radiated patients has a multifactorial origin, although vascular and neuronal damage and the acceleration of atherosclerosis seem to be decisive. The onset of ED is usually delayed, related to each patient's age and comorbidities.32 According to a recent meta-analysis where a total of 103 studies and 26269 patients were included, the prevalence of ED in radiated patients is 34% at one year, 39% at 2 years, 44% at 3 years and 57% at 5 years. However, only cohort studies were included in this meta-analysis, without a control group, where residual confounding factors, such as age, follow-up, drop-out rate, and association with hormonal deprivation, cannot be excluded. In addition, the great variability should be highlighted in the inclusion of patients, the description of their characteristics, the modalities of radiation treatment, and fundamentally in the definition of ED, with more than 7 questionnaires used and 23 different cut-off points.34,35 The percentage is quite similar among the different EBRT modalities, even taking into account new emerging techniques (IMRT, escalated dose sessions or image-guided radiation), with 34–64% in the EBRT with a three-dimensional configuration, and 34–80% in BT. Again, the higher the dose, the greater the risk of ED.32 In fact, no differences have been found between BT and EBRT.34

The incidence of grade 2 intestinal toxicity (diarrhea, presence of mucus in stool, moderate abdominal and rectal pain) is 5% for IMRT compared with 13% for EBRT with a three-dimensional configuration.33

Comparative studies: active surveillance vs surgery vs radiotherapyThrough a recent systematic review, following the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) and the Cochrane review principles, and under the supervision of a panel of experts from the EAU (European Association of Urology) who create the PCa Clinical Guidelines, the extraction has been possible of data with the highest level of scientific evidence published to date in relation to comparative studies between AS, RP, EBRT and BT.36 This review included 3 randomized clinical trials and 15 non-randomized comparative studies. The aim was to compare functional outcomes related to quality of life among the classic treatment options for localized PCa.

Comparative clinical trials. The main trial is the ProtecT study, which included 1643 patients randomized to AS (545), ORP (58.6% ORP) (553) or EBRT (three-dimensional configuration associated with hormonal block) (545) with low and intermediate risk PCa, which were evaluated using the EPIC questionnaire (Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite) and followed-up for 6 years.37 RP produced the greatest negative effect on continence at 6 months, and despite improvement, it remained clearly more affected than those in the EBRT and AS groups at all points of follow-up, which in turn were similar among themselves. The obstructive and irritative symptoms were more pronounced in the EBRT group at 6 months, but later they returned to be similar to those at the beginning of the study and those of the RP and AS groups. Erectile function was reduced in all groups at 6 months, being worse in the RP group at all cut-off points, but a slight improvement was observed at 3 years. Although milder, the findings were similar for the EBRT group. In contrast, the AS group experienced a progressive worsening of erectile function year after year, but always lower than the rest of the groups. The intestinal function (primarily hematochezia) did not vary between the RP and AS groups but was worse in the EBRT group, especially at 6 months, although this deterioration did not reach the threshold of clinical relevance.38 There were no differences in overall quality of life at 5 years of follow-up.37

In the other two clinical trials, which had less strength due to their small sample size and short follow-up, a comparative study was performed in patients with low-risk PCa comparing RP and low-dose BT.39,40 The SPIRIT study (Surgical Prostatectomy Versus Interstitial Radiation Intervention Trial) included 168 patients (66 RP vs 102 BT), with favorable results for BT in the domains of urinary function and sexual function, with no differences in the intestinal function of the EPIC questionnaire, after an average follow-up of 5.2 years. However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as only 19% of patients were randomized, and the study closed prematurely due to poor recruitment.39 The other clinical trial included 200 patients (100 RP vs 100 BT), showing an increase in obstructive and irritative voiding and bowel symptoms in patients treated with BT during the first year, with incontinence being more frequent in patients who underwent surgery, with no significant differences in the sexual function between both treatments after the first year of follow-up, and with no differences between the functional results of both groups at 5 years.40

Non-randomized comparative studies. Non-randomized comparative, prospective, or retrospective studies have significant limitations. They are observational cohort studies where there is a risk of an inherent selection bias, with heterogenous groups for various characteristics from the start, making it difficult to draw accurate conclusions. Many studies have been published related to short-term comparative studies (with a follow-up period of 2–3 years), all of which coincide with their findings.41–43

Regarding continence, the results were clearly worse for RP, primarily 2 months after the intervention and while there was a tendency for subsequent recovery, the initial stage was not reached after 2 years of follow-up. The patients who underwent EBRT and BT experienced minimal declines in continence, of which was only very minor in the first few months. Significant improvement to the previous state in regards to irritative and obstructive symptoms was observed in patients undergoing surgery, with initial moderate worsening (2–6 months) in patients receiving EBRT and BT, with subsequent recovery after 2 years of follow-up.

In regards to sexual function, the 3 options resulted in significant erectile dysfunction, although RP was clearly associated with a greater degree with respect to EBRT and BT,41–43 and with a tendency to equalize at 2 years. In terms of intestinal function, namely, intestinal symptoms such as urgency, frequency, abdominal pain, fecal incontinence, or hematochezia, there were no incidences of these in patients who underwent surgery. However, there was significant impact with no tendency of subsequent recovery in patients treated with EBRT and BT. In medium- and long-term studies with a follow-up of 5–15 years, the functional results had a tendency to vary with respect to those achieved in short-term studies. The PCOS (Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study) is the most representative.44

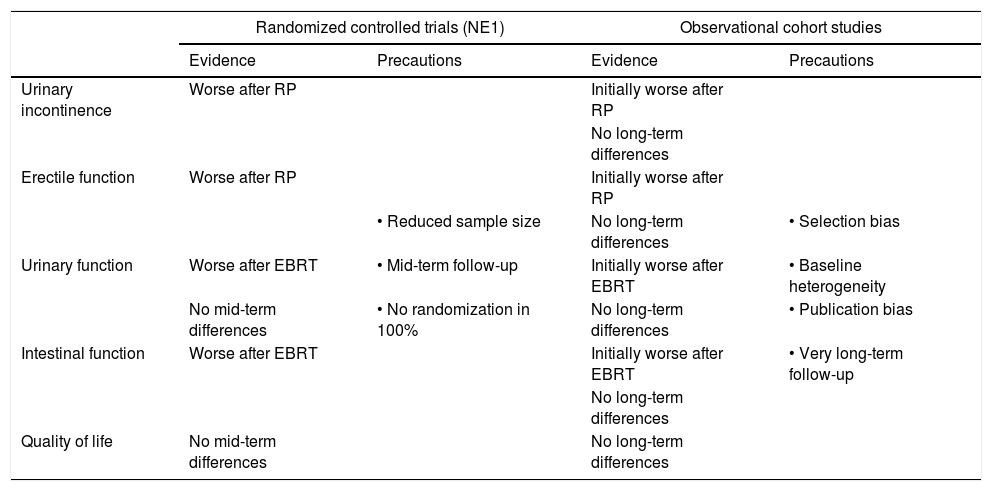

In terms of incontinence, the results were worse after 5 years for patients who underwent intervention in comparison to those who received radiotherapy. This difference however, disappeared after 15 years of follow-up, with incontinence being comparable between both groups. A similar phenomenon could be observed in relation to sexual function. This long-term comparison of incontinence and erectile dysfunction can be interpreted as an inherent phenomenon of aging.44 However, these results should also be interpreted with caution since they include patients with PCa diagnosed in the 1990s, where both surgical techniques and radiotherapy techniques had not yet been developed as we understand them today (Table 2).

Comparison of the functional results after AS, RP, EBRT and BT in the management of localized PCa, stratified by the evidence given by the design of the studies.

| Randomized controlled trials (NE1) | Observational cohort studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence | Precautions | Evidence | Precautions | |

| Urinary incontinence | Worse after RP | Initially worse after RP | ||

| No long-term differences | ||||

| Erectile function | Worse after RP | Initially worse after RP | ||

| • Reduced sample size | No long-term differences | • Selection bias | ||

| Urinary function | Worse after EBRT | • Mid-term follow-up | Initially worse after EBRT | • Baseline heterogeneity |

| No mid-term differences | • No randomization in 100% | No long-term differences | • Publication bias | |

| Intestinal function | Worse after EBRT | Initially worse after EBRT | • Very long-term follow-up | |

| No long-term differences | ||||

| Quality of life | No mid-term differences | No long-term differences | ||

LE – level of evidence, RP – radical prostatectomy, EBRT – external radiotherapy.

The evidence in relation to the functional results from the use of main therapies in cases of localized PCa is scarce. Randomized clinical trials are anecdotal and of low potency, and the bulk of the literature focuses on comparative prospective or retrospective series with a clear selection bias that must be taken into account. Based on the evidence currently available, each of the treatment options for clinically localized PCa produces a different impact on the specific quality of life for a period of up to 6 years after treatment. Patients managed with AS have a good quality of life in general, better than patients undergoing radical treatments. Surgery infers a pronounced negative impact on urinary and sexual function when compared to AS and EBRT, while EBRT has a greater negative impact on bowel function when compared to AS and RP. The findings of the aforementioned systematic review36 support the assertion that active surveillance offers a good alternative to radical treatments in patients who wish to prioritize functional outcomes. The findings provide a basis for informing patients about the impact of radical treatments on quality of life.

Ablation therapiesTraditionally, ablation or minimally invasive therapies have been used when radical procedures cannot be performed (RT, EBRT, BT) due to the associated comorbidities, or as a rescue treatment after a previous radical process, fundamentally RT, with the advantage that they can be repeated, filling the gap between active surveillance and more aggressive therapies. The improvement of these techniques has allowed for increased effectiveness and safety.5 As these cannot be considered as radical treatments, their oncological control is not comparable with the previously described treatments.

HIFU (high-intensity focused ultrasound). Functional results from HIFU are highly varied. The main complications after treatment are urinary retention (<1–20%), lower urinary tract infections (1.8–47.9%), UI (<1–34.3%) and ED (20–81.6%).45 The morbidity of the voiding symptoms seems to be reduced with the combination of the previous transurethral resection of the prostate. On the other hand, a review on the functional results after partial prostatic ablation by HIFU has recently been published, in which both the UI rates (0–10%) and the ED rates (0–48%) are lower in relation to those obtained with global treatment on the prostate.46 The absence of standardization of the inclusion criteria and follow-up protocols, the marked heterogeneity between the included studies, and the absence of long-term studies, make it necessary to be cautious when affirming the oncological efficacy and safety of this modality of focal treatment.

Cryotherapy. Advances in imaging technology and 4th generation cryotherapy techniques have allowed the design of a targeted, or even unifocal, therapy with oncological control similar to cryoablation of the entire gland and with better functional results than devices used until now.47 For example, in a study that included 393 patients, on voiding symptoms, the IPSS questionnaire showed an improvement of 4 points one year after treatment (p<0.001) and the urgency and urinary retention rate was 27.7%. Regarding erectile function, there was no difference in the score with the SHIM (Sexual Health Inventory For Men) questionnaire compared to those obtained before treatment (p>0.7), and the rate of de novo erectile dysfunction was only 9.2%, but without any tendency of improvement during follow-up.48

Comparative studies: surgery vs radiotherapy vs cryotherapyThe comparative evaluation of ablation therapies with the rest of the treatments for localized PCa can be extracted from a relatively recent meta-analysis.49 Accordingly, the UI rate for cryotherapy is similar to that for EBRT (<1%, OR 0.41 (0.02–19.0) p 0.67), and is lower than that for RP (OR 0.02 (<0.01–0.39), p>0.99) in the first year, but not at 5 years, where no differences are observed (OR 0.12 (<0.01)–16.8) p 0.81). The rate of ED is lower compared with RP, however this difference is not statistically significant (0–40%, OR 0.69 (<0.01–13.1) p 0.58). The incidence of dysuria, episodes of urinary retention and rectal pain is similar to that produced by EBRT. On the other hand, the UI rate produced by HIFU is similar to that produced by EBRT (OR 2.4 (0.28–19.5) p 0.18) and lower than that produced by RP (OR 0.06 (0.01–0.48) p>0.99) per year, which is similar at 5 years (OR 1.9 (0.04–12.1) p 0.38). The rate of ED is significantly lower with HIFU compared to RP, but this difference is not statistically significant (OR 0.57 (0.01–352) p 0.72). The incidence of dysuria, episodes of urinary retention and rectal pain is similar to that produced by EBRT.49 Another more recent meta-analysis,50 which included a total of 7 studies with 1252 patients, comparatively studied the functional results of cryotherapy and EBRT. In this meta-analysis, no differences were found in relation to voiding or sexual symptoms between cryotherapy and EBRT, however, there was a trend toward greater voiding symptoms after EBRT and sexual symptoms after cryotherapy.50 That said, despite the attractiveness of the results of these reviews, the comparative differences between treatments are relatively weak and there are no randomized clinical trials published in this regard.

ConclusionsAttempting to outline the heterogeneity of the data obtained from the different comparative studies, while aware of the limitations of the reviews included, the functional results of the different management options for localized PCa can be summarized in the following facts; AS offers the best possible functional results compared to the rest of the options; RP produces low UI and moderate ED rates; EBTR and BT produce moderate urinary and intestinal symptoms and ED, although they are milder with BT. The latest generation ablation therapies used as focal treatments generate functional results that are superimposable to those of EBRT or BT. Of all the affected functions, sexual dysfunction is the most frequent, with 90% of patients affected, especially if they have suffered from previous deterioration.

Given the high survival rate with localized PCa, it is important to know the long-term effects of each of the treatment options. In our daily clinical practice, it is extremely important to warn of the expected functional results and the most common symptoms that affect quality of life when considering a therapeutic option, within the context of all of them are safe from an oncological perspective.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments have been conducted in humans or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of the dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that patient data does not appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.