The aim of this study was to compare fertilisation, pregnancy rates and perinatal outcomes in patients undergoing intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) due to oligozoospermia.

MethodsA total of 166 patients with oligozoospermia who underwent an ICSI procedure were included in the study. The subjects were divided into two groups according to the sperm retrieval technique used: group 1, ejaculated semen (n=111); group 2, surgical sperm retrieval (n=55).

ResultsAlthough the clinical pregnancy rate was lower in group 2, the difference was not statistically significant (36.4% vs. 42.3%, p=0.460). The difference between fertilisation and take-home baby rates of the groups were not significantly different, either (p=0.486, p=0.419, consecutively).

ConclusionTwo different sperm retrieval techniques used for ICSI had no statistically significant difference on intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes in oligozoospermic patients.

El objetivo de este estudio fue comparar la fertilización, las tasas de embarazo y los resultados perinatales en pacientes sometidos a inyección intracitoplasmática de espermatozoides (ICSI) por oligozoospermia.

MétodosUn total de 166 pacientes con oligozoospermia que se sometieron a un procedimiento ICSI se incluyeron en el estudio. Los sujetos se dividieron en dos grupos según la técnica de recuperación de espermatozoides utilizada: grupo 1, semen eyaculado (n=111); Grupo 2, recuperación quirúrgica de espermatozoides (n=55).

ResultadosAunque la tasa de embarazos clínicos fue menor en el grupo 2, la diferencia no fue estadísticamente significativa (36.4% vs. 42.3%, p=0,460). La diferencia entre las tasas de fecundación y de bebés a domicilio de los grupos tampoco fue significativamente diferente (p=0.486, p=0.419, consecutivamente).

ConclusiónDos diferentes técnicas de recuperación de espermatozoides utilizados para la ICSI no tenía ninguna diferencia estadísticamente significativa en la inyección de espermatozoides intracitoplasmáticos resultados en pacientes oligozoospermicos.

Oligozoospermia, a common finding in male infertility and consistent with the 5th percentile for fertile men, is defined by the World Health Organization as less than 15millionsperm/mL.1,2 Severe oligozoospermia is defined as a concentration of less than 5×106sperm/mL.3 Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) is the preferred method of management in severe oligozoospermia.4

Palermo et al.5 reported the first successful pregnancy as a result of the ICSI method they performed on four patients, three of them had oligoasthenoteratospermia and one of them asthenoteratospermia. One year later, using ICSI, higher fertilisation and pregnancy rates were reported in patients where standard in vitro fertilisation-embryo transfer (IVF-ET) had failed.6 In that study, the patients were defined as having a less then 5% chance of fertilisation per cycle or less than 500,000 progressive motile spermatozoa in whole ejaculate. However, Harari et al.7 and Nagy et al.8 postulated that sperm parameters do not affect fertilisation and pregnancy rates.

In ICSI, the material required for the procedure is obtained either surgically via testicular sperm extraction (TESE), microsurgical epididymal sperm aspiration and percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration or from freshly ejaculated semen.9 As surgical sperm retrieval is an invasive surgical procedure, it is generally not preferred by physicians and patients.10

With regard to oligozoospermia, there is no consensus on whether surgical sperm retrieval or freshly ejaculated semen should be used in ICSI procedures, and there are conflicting results in the literature regarding ICSI outcomes using ejaculated or surgical sperm retrieval. Ben-Ami et al.10 claimed that surgical sperm retrieval was more suitable for patients who failed to conceive from ICSI using ejaculated spermatozoa, with the former resulting in higher pregnancy rates. Strassburger et al.11 argued that the origin of the sperm (testicular or ejaculation semen) affected ICSI outcomes in assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles performed in cases of oligozoospermia. Stalf et al.12 also asserted that the origin of the sperm affected fertilisation rates, clinical pregnancy rates and live birth rates. Conversely, other studies, including a meta-analysis, showed that the technique used to retrieve the spermatozoa had no effect on outcomes.12–14 A recent meta-analysis also concluded that there were no difference between two sperm retrieval methods (TESE and freshly ejaculated semen) with regard to intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes in ART cycles in cases of cryptozoospermia.15

In this study, we aimed to compare the impact of surgical sperm retrieval and ejaculated semen on fertilisation, pregnancy rates and perinatal outcomes in ART cycles in cases of oligozoospermia.

MethodsData on patients with oligozoospermia who had undergone fresh ET-ICSI cycles at Zekai Tahir Burak's Women's Health Research and Education Hospital, Reproductive Endocrinology Department between September 2010 and March 2012 were reviewed. The hospital is a tertiary referral centre in Ankara for patients throughout the country, and it performs an average of 500 ICSI-IVF cycles per year. Oligozoospermia was defined according to the criteria of the World Health Organization.2 The criteria for inclusion in the study were cases with severe nonobstructive type oligozoospermia (<5millionsperm/mL) who had undergone just one ICSI cycle following two sperm retrieval methods (TESE or freshly ejaculated semen). If there were no sperm in the semen, these patients were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria were a previous history of genital infection, varicocele, cryptorchidism, exposure to gonadotoxin and hypogonadism. Standard chromosome analyses (karyotype) and screenings for Yq microdeletions were performed in all subjects. Subjects with normal karyotypes and those who did not show signs of Yq microdeletions were enrolled in the study. This study was approved by the ethics committee and institutional review board of Zekai Tahir Burak's Women's Health Research and Education Hospital.

The primary outcome measure was the clinical pregnancy rate. The secondary outcome measures included the fertilisation and take-home baby rates.

Semen retrieval techniqueSemen samples were collected by masturbation after 2–3 days of abstinence, and then the samples were allowed to liquefy for at least 20min at 37°C before analysis. The concentration, motility and morphology of the fresh sperm were assessed, followed by centrifugation.16 Subsequently, the semen precipitate was placed in an injection dish containing several droplets of culture medium, and a meticulous extended sperm search was undertaken to find viable motile spermatozoa for ICSI.

Surgical sperm retrieval techniqueTESE was performed under local anaesthesia and intravenous sedation, according to the previous reported procedure.17 Testicular parenchyma was observed at 40× magnification, using an operative microscope (Ziess, Oberkochen, Germany), and resection of the dilated seminiferous tubules was carried out to find viable spermatozoa for ICSI. Using two insulin syringes, the excised tubules were transferred to a sterile plate and washed in warmed Ham's F10 media to eliminate red blood cells. The washed tubules were then minced in a sterile plate containing the warmed medium. Cells lysate and debris were removed by centrifugation at 300×g for 5min to obtain a pellet containing viable spermatozoa for ICSI.18

Ovarian stimulation and oocyte retrievalControlled ovulation stimulation was achieved using the long protocol. First, pituitary down-regulation was performed with a GnRH agonist. Then, the ovaries were stimulated by exogenous gonadotropins. The GnRH agonist leuprolide acetate (Lucrin; Abbott Cedex, Istanbul, Turkey) was administered subcutaneously daily from day 21 of the preceding luteal phase (0.5mg/day, sc) until menstruation, and then the dose was decreased to 0.25mg/day until ovulation was triggered. Recombinant FSH (Puregon; Organon, Oss, the Netherlands or Gonal F; Serono, Istanbul, Turkey) was used for stimulation. The initial gonadotropin dose used was individualised according to the patient's age, baseline serum FSH concentration on day 3, body mass index and previous response to ovarian stimulation. The starting regimen was fixed for the first 3 days (100–225IUrecombinantFSH/day). Thereafter, the dose of gonadotropin was adjusted according to the individual ovarian responses, which were monitored by measuring serum estradiol levels and transvaginal ultrasonography. Ovulation was triggered by administration of 250IU recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) (Ovitrelle, Serono, Istanbul, Turkey) when at least two follicles reached 18mm in diameter. Oocytes were retrieved 36h after the HCG injection, and ICSI was performed for all IVF-ET patients. ETs were performed on day 3.

Statistical analysisSPSS 15 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software was used for the statistical analyses. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test for normal or abnormal distributions of the continuous variables. An independent samples T-test was used for the between-group comparisons of the continuous variables with normal distributions. The data are expressed as the mean±SD. The Mann–Whitney U test was applied for variables with a non-normal distribution. The data are expressed as median and inter-quartile ranges. Categorical data was analysed by Pearson's chi-square test, and Fisher's exact test was applied if the expected frequency was less than 5 in >20% of all cells. p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Power analysis and sample size calculations were carried out using the G*Power 3.0.10 programme (Franz Faul, Universität Kiel, Kiel, Germany).

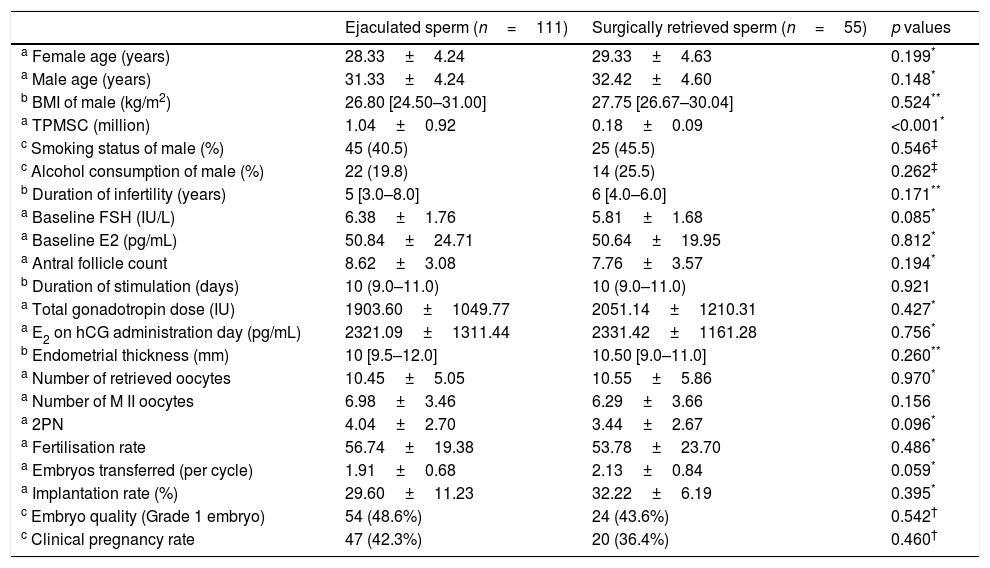

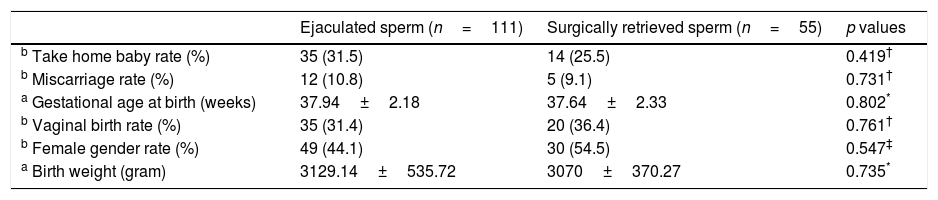

ResultsA total of 254 patients were initially diagnosed with oligozoospermia. Of them, 166 patients were eligible for the study. The patients were divided into two groups according to the sperm retrieval technique used: group 1, ejaculated semen (n=111); group 2 surgical sperm retrieval (n=55). The karyotype analysis was normal (46, XY), and none of the patients had Y chromosome microdeletions. The clinical and laboratory parameters of the groups were similar (Table 1). The perinatal outcomes of the groups were also similar (Table 2). All pregnancies led to at-term deliveries, with normal foetal weights, and there were no major or minor malformations. Despite decreased clinical pregnancy (42.3% vs. 36.4%) and take-home baby (31.5% vs. 25.5%) rates in group 2, there were no statistically significant differences in the clinical pregnancy and take-home baby rates between groups 1 and 2 (p=0.460 and p=0.419).

Clinical and laboratory parameters of the groups.

| Ejaculated sperm (n=111) | Surgically retrieved sperm (n=55) | p values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a Female age (years) | 28.33±4.24 | 29.33±4.63 | 0.199* |

| a Male age (years) | 31.33±4.24 | 32.42±4.60 | 0.148* |

| b BMI of male (kg/m2) | 26.80 [24.50–31.00] | 27.75 [26.67–30.04] | 0.524** |

| a TPMSC (million) | 1.04±0.92 | 0.18±0.09 | <0.001* |

| c Smoking status of male (%) | 45 (40.5) | 25 (45.5) | 0.546‡ |

| c Alcohol consumption of male (%) | 22 (19.8) | 14 (25.5) | 0.262‡ |

| b Duration of infertility (years) | 5 [3.0–8.0] | 6 [4.0–6.0] | 0.171** |

| a Baseline FSH (IU/L) | 6.38±1.76 | 5.81±1.68 | 0.085* |

| a Baseline E2 (pg/mL) | 50.84±24.71 | 50.64±19.95 | 0.812* |

| a Antral follicle count | 8.62±3.08 | 7.76±3.57 | 0.194* |

| b Duration of stimulation (days) | 10 (9.0–11.0) | 10 (9.0–11.0) | 0.921 |

| a Total gonadotropin dose (IU) | 1903.60±1049.77 | 2051.14±1210.31 | 0.427* |

| a E2 on hCG administration day (pg/mL) | 2321.09±1311.44 | 2331.42±1161.28 | 0.756* |

| b Endometrial thickness (mm) | 10 [9.5–12.0] | 10.50 [9.0–11.0] | 0.260** |

| a Number of retrieved oocytes | 10.45±5.05 | 10.55±5.86 | 0.970* |

| a Number of M II oocytes | 6.98±3.46 | 6.29±3.66 | 0.156 |

| a 2PN | 4.04±2.70 | 3.44±2.67 | 0.096* |

| a Fertilisation rate | 56.74±19.38 | 53.78±23.70 | 0.486* |

| a Embryos transferred (per cycle) | 1.91±0.68 | 2.13±0.84 | 0.059* |

| a Implantation rate (%) | 29.60±11.23 | 32.22±6.19 | 0.395* |

| c Embryo quality (Grade 1 embryo) | 54 (48.6%) | 24 (43.6%) | 0.542† |

| c Clinical pregnancy rate | 47 (42.3%) | 20 (36.4%) | 0.460† |

p<0.05 is statistically significant.

Perinatal outcomes of the groups.

| Ejaculated sperm (n=111) | Surgically retrieved sperm (n=55) | p values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| b Take home baby rate (%) | 35 (31.5) | 14 (25.5) | 0.419† |

| b Miscarriage rate (%) | 12 (10.8) | 5 (9.1) | 0.731† |

| a Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 37.94±2.18 | 37.64±2.33 | 0.802* |

| b Vaginal birth rate (%) | 35 (31.4) | 20 (36.4) | 0.761† |

| b Female gender rate (%) | 49 (44.1) | 30 (54.5) | 0.547‡ |

| a Birth weight (gram) | 3129.14±535.72 | 3070±370.27 | 0.735* |

p<0.05 is statistically significant.

In the present study, the impact of two different sperm retrieval methods (surgically retrieved or ejaculated) on fertilisation, pregnancy and take-home baby rates in ART cycles in cases of oligozoospermia infertility were compared. Despite the decreased fertilisation (56.74±19.38 vs. 53.78±23.70), clinical pregnancy (42.3% vs. 36.4%) and take-home baby (31.5% vs. 25.5%) rates in group 2, the difference between the groups did not reach statistical significance (p=0.460, p=0.486, p=0.419, respectively).

There are conflicting results in the literature regarding the results of ICSI with different sperm retrieval methods (negative or no correlation) in men with oligozoospermia. According to some researchers, there is no correlation between fertilisation rates and the sperm retrieval method (surgical retrieval or freshly ejaculated semen), and the method used does not adversely affect fertilisation rates in ART cycles in cases of oligozoospermia.19–22 Some studies have demonstrated that fertilisation rates were better when using testicular sperm rather than ejaculated semen, even after freeze-thawed cycles,10,23,24 whereas others have reported that they were lower when surgical sperm retrieval (testicular sperm) rather then ejaculated semen was used.8,25 In the present study, no difference was found between two groups (freshly ejaculated semen or surgical sperm retrieval) regarding fertilisation rates.

With regard to the effect of different sperm retrieval methods on the quality of the embryo, some studies reported that the use of testicular sperm in the ICSI procedure worked better and enabled the growth of more qualified embryos, as was found with fertilisation rates, whereas others argued that no difference existed.19,23,25 In the present study, no statistically significant difference was found between the groups in the embryo quality.

When evaluated from the perspective of clinical pregnancy rates, some studies concluded that testicular sperm produced better outcomes,10,19,24,26 whereas others found no difference in clinical pregnancy rates between the two methods (TESE and freshly ejaulated semen),25 as was the case in the present study.

In an earlier study, the sperm was retrieved from ejaculated semen in the first ART cycle for the ICSI procedure, and surgically testicular sperm retrieval was used if the first ART cycle failed in the same couple.10 In the present study, the sperm used in each ART cycle for the ICSI procedure was either surgically retrieved (testicular sperm) or obtained from ejaculated semen.

According to the literature, post-testicular injury (changes in spermatozoa and damage of sperm DNA) to spermatozoa occurs during the transfer from the epididymis and seminiferous tubules to the vagina, and this has a negative effect on ICSI outcomes. However, in the surgical sperm retrieval technique, it has been suggested that the spermatozoa maturation could not be completed because the ICSI method itself by passed natural barriers. Furthermore, the impact of the morphology and motility of the sperm selected by the embryologist for use in the ICSI procedure on subsequent outcomes is unclear.21,26,27 The conflicting results in the literature, including those of the present study, may be due to the different numbers of patients included in the studies, treatment techniques and outcome measures. For instance, some studies reviewed outcomes following consecutive cycles with different sperm retrieval methods in the same couples, whereas others studied only the first cycle in each couple.

Sperm DNA damage is known to be associated with adverse reproductive outcome, including fertilisation, embryo quality, blastocyst formation, implantation and spontaneous miscarriage. The cause of sperm DNA fragmentation is still unknown. However, chromatin remodelling defects during spermiogenesis and oxidative stress is considered to be the cause of this situation. It is claimed that this negative effect is bypassed by TESE.28,29 It might be useful to perform sperm DNA fragmentation tests in severe oligozoospermia. There is need studies to elicit positive reproductive outcomes with testicular sperm.

Visible bleeding, infection or testicular damage can occur during the surgical procedure and have negative effects on spermatogenesis. Thus, this method of sperm should only be used after non-surgical methods (freshly ejaculated semen) have failed.

The limitations of this study are its retrospective design and small sample size. The primary aim of this study was to determine the difference in clinical pregnancy rate between groups. According to the post hoc power calculation, group sample size of 111 and 55 achieve 29% power to detect a difference of 0.059 between the null hypothesis that both group proportions are 0.423 and the alternative hypothesis that the proportion in the other group is 0.364 with a significance level of 0.05. In the post hoc power analysis, the power of the study was 0.291 for clinical pregnancy rates, 0.311 for take-home baby rates and 0.569 for fertilisation rates.

In conclusion, although the sample size was small, and this was a retrospective study, no significant difference was found in perinatal outcomes between ejaculated and surgical sperm retrieval in cases of oligozoospermia treated with ICSI-ART. Concerning the adverse effects of TESE, including haematoma, infection, pain, changes in testosterone levels and equal success rates, the use of ejaculated sperm, when available, should be preferred to surgical sperm retrieval.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the subject matter or materials discussed in this article.

None.