Parents of multilingual children often need to make choices about the transmission of languages in the next generations. The aim of this scoping review is to examine recent evidence addressing the language views and practices of multilingual families, to identify key patterns regarding the use of language(s) at home. Four databases were searched systematically in June 2023 including a total of 45 articles. Studies where children had language and/or communication disorders were included. The findings show that parents make their linguistic choices based on their own attitudes and experiences. They also consider professional advice, which does not always align with their views. The evidence reveals similarities between families with and without language and/or communication disorders, despite showing particularities related to the child's condition. Few studies were found where children had disorders, highlighting the need of further research on the matter to provide knowledge that could be useful in clinical settings.

Las familias multilingües a menudo tienen que tomar decisiones sobre la transmisión de lenguas en las siguientes generaciones. El objetivo de esta revisión es examinar evidencia reciente sobre las perspectivas y prácticas lingüísticas en familias multilingües, identificando patrones en relación con la elección de lenguas en el hogar. Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática en cuatro bases de datos en junio de 2023 incluyendo un total de 45 estudios. Se incluyeron familias con niños/as con y sin trastornos del lenguaje y/o comunicación. Los resultados revelan que los padres toman decisiones según sus propias perspectivas y experiencias lingüísticas. También consideran recomendaciones profesionales, aunque no siempre coinciden con sus preferencias. La evidencia muestra similitudes entre familias con y sin trastornos del lenguaje/comunicación, aunque existen particularidades según el trastorno. Se encontraron escasos estudios que incluyeran casos con trastornos, destacando la necesidad de continuar investigando esta área para expandir el conocimiento aplicable en entornos clínicos.

The growth of intercultural couples and multilingual1 families is a phenomenon that is now part of our societal structure. This cultural diversity has been a topic of interest for several years now (Pérez, 2022), leading to a growing number of studies addressing the linguistic and cultural dynamics of multilinguals.

According to the United Nations, in the year 2020 there were around 281 million international migrants around the globe (3.6% of the world population), which is an addition of 128 million people when comparing it to an estimation made 30 years earlier (World Migration Report, 2022). Globalization is a reality that cannot be ignored, so it is no longer a surprise to see a heterogeneity in the languages or cultures among friends and between couples, often leading to multilingualism in the following generations.

The multilingual family and language policiesGrowing up in a multilingual environment, moving to a different country, going through international adoption, or being raised in a setting where at least one of the parents speak a minority language are just a few of the many situations a child might experience to become a multilingual person (Braun & Cline, 2014; Grech & McLeod, 2012; Nieva, 2019).

The linguistic skills of those children will vary depending on different factors such as their socioeconomic status, amount and quality of language exposure (Schwartz, Moin, & Leikin, 2011), the decisions their parents make about language use, or the setting they grow up in Bayley, Schecter, and Torres-Ayala (1996), so when couples of different cultural backgrounds start a family, they need to make (conscious or unconscious) choices about the place they are going to raise their children in, the language they are going to use, as well as how they are going to educate – and transfer values to – their offspring (Moratalla, 2022).

With regards to language choice and use, Spolsky (2004) introduces the concept of Family Language Policies. These policies are the result of an interaction between language practices (use), language management (planning), and the beliefs and values assigned to the languages they or their children are exposed to Spolsky (2007). Family language policies are subject to change across families and can also vary with time, as families have their own priorities, views, expectations and experiences regarding the language(s) they speak within a variety of contexts and environments. In addition to family language policies, the individual practices that parents do to transmit the different languages will be referred to in this paper as language transmission strategies (or language strategies) (Juan-Garau & Pérez-Vidal, 2001).

Beliefs and language valueThe beliefs about a language and the value assigned to it are inherently related. De Luca (2018) affirms that giving proper value to one's mother tongue promotes a sense of pride that would have a positive effect on how a person perceives their own and other languages.

Nonetheless, it is not only the individual perception of a language what would play a role in adding value to it, but also the societal attitudes and institutional actions. From a linguistic point of view, all languages – spoken, signed, or written – are equal, as they meet all the needs required for a person to communicate with other people in their community (Moreno-Fernández, 2015). However, from a socio-economic perspective, languages are given different value and sometimes even used as an indicator of class (De Luca, 2018), and although the number of heterogeneous communities is growing, some world leaders still promote cultural assimilation and nationalism rather than cross-cultural interactions (Simon-Cereijido, 2018), leading to a language uniformity over diversity (Braun & Cline, 2014) that would support the differences in attitudes and values assigned to languages across the globe.

Nevertheless, it is clear that the views about languages will vary from person to person. Baker (1988) indicates that there are occasions where people demonstrate an inconsistency on their opinions in the case of minority/indigenous languages, showing positive public attitudes but a private skepticism. These circumstances cannot be dissociated from the motivations a person has to learn and/or teach a language to their offspring, which are strongly tied to their beliefs – as stated by Spolsky (2007). These motivations can be classified as integrative, where the motive is to become part of a community by learning a certain language; and instrumental, where the motives are mainly utilitarian (e.g., opportunities of employment) (Baker, 1988; Masgoret & Gardner, 2003). However, those definitions are linked to contextual and socioeconomic factors, leaving personal aspects such as emotional motivations out of the main frame. Therefore, in this review, the concept of language value will be addressed considering both contextual and personal perspectives.

Language transmission, culture and identityDuring the process of rearing children in a multilingual environment, it is primarily the role of the parents to transmit the heritage language (HL) and culture to their children (Gomashie, 2022) while also trying to integrate into the new community (Ferreira, Miglio, & Schwieter, 2019), but they might find difficulties due to the inevitably high exposure to the majority language or the language of instruction, the ability to contact with the extended family or the choice of language between siblings (Moratalla, 2022).

The external attitudes that the youth perceive about their language(s) while growing up may also play a role on the assimilation of their own linguistic and cultural identity from a young age, which in turn could have an effect on the home language use and maintenance (Gomashie, 2022; Gutiérrez-Clellen, 1999). If that is the case, negative attitudes and their consequences would limit the basic human right of any person to use and communicate in the language(s) they prefer (De Luca, 2018; Simon-Cereijido, 2018), and those limitations would tip the scale toward a situation of linguicism and ethnicism that could eventually lead to a language erasure that Skutnabb-Kangas (2019) would label as linguistic genocide.

For that reason, multilingual families could benefit from counting on a support system that advocates for the use of the home language in and out of their home setting. In this respect, professionals such as speech and language therapists or teachers would play an important role in the language development of the child (Dickinson, 2011) as well as their education, as the views and advice of practitioners could impact language choices and practices at home (Spolsky, 2012). However, despite the part that professionals can take on the language dynamics of multilinguals, they sometimes struggle to provide adequate support to families who speak minority languages or whose children present a language and/or communication disorder (e.g., developmental language disorder) (Moore & Pérez-Méndez, 2006; Nieva, Aguilar-Mediavilla, Rodríguez, & Conboy, 2020). There is evidence that supports a multilingual education and intervention regardless of the languages spoken or potential language difficulties or disorders (Gutiérrez-Clellen, 1999; Simon-Cereijido & Gutiérrez-Clellen, 2014). Various international expert panels have developed position papers on recommended practices for speech and language therapists who work with multilingual children in different linguistic contexts, defending a culturally responsive framework (McLeod, Verdon, & Bowen, 2013; Nieva, Conboy, Aguilar-Mediavilla, & Rodríguez, 2020; Stow & Pert, 2015). However, professionals may not be familiarized with the current practice guidelines or possess limited knowledge about the language development and skills of multilinguals. Therefore, speech-language therapists and other professionals would benefit from an evidence-based approach that is up to date with the current research.

Aims and research questionsGiven the context provided, the present study was developed to present up-to-date information that might be useful for professionals and other stakeholders, aiming to answer the following research questions:

- 1.

What aspects play a role in parents’ decisions regarding language choice and use in multilingual settings?

- 2.

How do parents transmit languages to their multilingual children?

- 3.

Is there evidence available about language attitudes and priorities of multilingual families with children with language and/or communication disorders?

Therefore, the aim of this review is to examine the available evidence addressing the language priorities of families who raise children in a multilingual environment, collecting information about parents’ views and use of their heritage/home language(s), and the factors that might influence their choice to transmit (or drop) their language(s) in the following generations. Furthermore, this review included studies where children could have language and/or communication disorders.

MethodsA scoping review was conducted to identify and analyze recent articles that addressed parental views and priorities regarding language maintenance and use in multilingual settings.

Inclusion criteriaThe studies included in this review were articles published between 2017 and 2023, excluding dissertations. It was required that the studies addressed any aspect related to family language policies, preferences and priorities regarding language choice and maintenance of families with multilingual children, as well as their views and attitudes toward their own and other languages. It was a requirement that the studies included information about parents’ language perspectives, even though the authors did not exclude those where the children expressed their views in addition to the parents. In addition, articles where there were children with speech, language and/or communication disorders (such as Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) – previously known as Specific Language Disorder(SLD) or Primary Language Impairment (PLI) – (Bishop, Snowling, Thompson, & Greenhalgh, 2017) or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) were not excluded to provide information about different language development settings in multilingual families. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were reviewed, and they could be written in English, Spanish, Galician, Catalan and/or Portuguese. The studies had to address oral language development, excluding those that were focused on sign language, written language as well as augmentative or alternative communication systems.

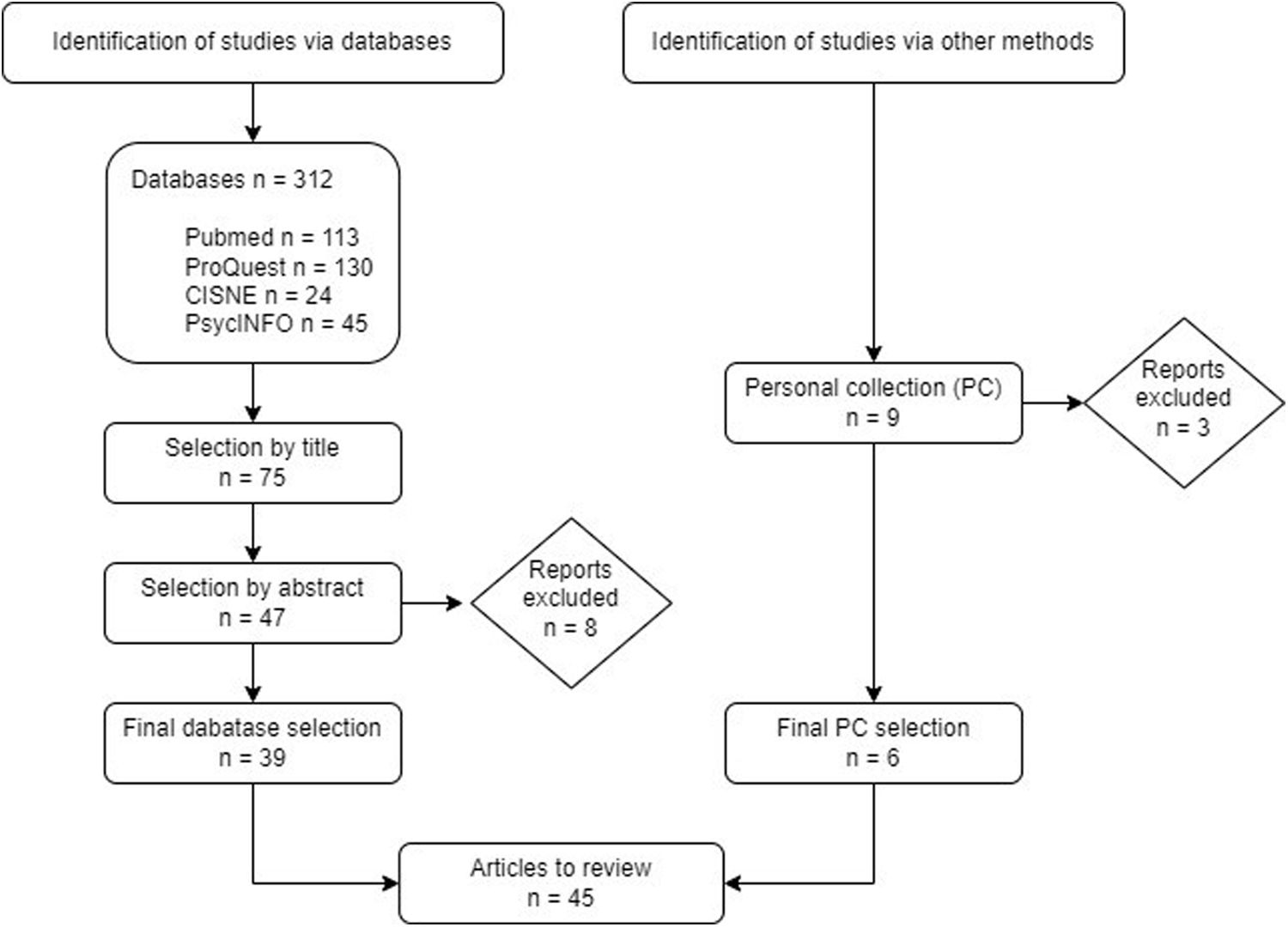

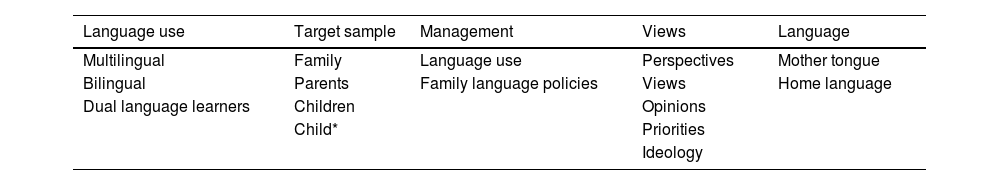

Search methodsThe language used for the article search was English, however the authors also reviewed studies written in other languages. An initial search of articles was undertaken between June and September 2022 with first a broad search to examine the state of art, followed by an in-depth search in PubMed, ProQuest and PsycINFO databases, with an additional search via CISNE database as it would provide access to articles archived in different university libraries. The search of articles was updated in July 2023, using the same databases. Table 1 shows the search words included in the databases. The first selection of articles was made according to their title and keywords, followed by an abstract revision to make the final choice of studies to review. In addition to that, a manual search was also performed examining articles cited in different studies as well as publications of authors of reference on the field. After a thorough reading of the articles, one last final screening was made to remove those that were not fully related to the aims of this study.

Data organizationAn Excel database was created to provide easy access to the search methods and procedure, showing a structured summary of the databases, keywords, and selected studies. The authors followed the PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews to develop this study (Tricco et al., 2018).

To organize the information extracted, each article was synthesized in a table that included the title and author(s) of the study, date of publication, geographical location of the study, sample information (number of participants, nationality(-ies), place of residence, languages spoken and potential language disorders), study design and methods, as well as the main findings of the study, quotes, possible limitations, and references that might be interesting for the review.

ResultsDuring the article search, a total of 312 entries were found with the introduction of the keywords in the selected databases. Of this search, 75 articles were potentially relevant for this review by reading the title. When considering the abstract of the studies, 47 were included, but 5 of them were duplicated and others presented information that deviated from the objective of this review, thus, at this stage, the final number of articles to analyze was 39. An addition of 6 articles from the personal collection of the authors was included, leaving a total of 45 articles to review. Fig. 1 shows the article selection process.

The articles included are empirical studies except for two that were reviewed because their content was considered of interest for this paper. The studies follow mainly a qualitative methodology and are located in several countries of Europe, America, Asia and Oceania, so this review includes the experiences of families who speak a variety of languages in different linguistic and cultural contexts. The families in the studies were of mixed origins and families who lived outside their home country, but there were also monolingual parents who opted for a multilingual education in their country of origin.

This section collects the information available in recent studies about language attitudes and practices of multilingual families regarding a multilingual education and the use of the heritage language(s). The articles were reviewed through an inductive approach with its focus on the research questions. Common topics were found across the different studies that were then organized in various categories discussing: (1) parental language attitudes and home-language maintenance, (2) the influence of external attitudes in the use of the home language, and (3) the choice of different language-transmission strategies and its challenges (see Table A1 in appendix A). Additionally, since there were also articles that discussed similar issues in families whose children might have language and/or communication disorders, those studies are clustered in their own separate section: (4) families where children have communication disorders or disabilities (see Table A2 in appendix A).

Parental language attitudes and home-language maintenanceThe studies included in this section addressed the personal attitudes and ideologies of parents toward their and other languages when it comes to managing the use of languages at home. These aspects did not necessarily have to be the main aims of the studies but had to be referenced as part of the elements considered when making linguistic decisions.

One common finding among the studies was the positive attitude parents have toward multilingualism and learning more than one language (Berardi-Wiltshire, 2017; Kostoulas & Motsiou, 2020), usually holding the idea of ‘the more languages, the better’ and the advantages that a multilingual education could bring to their children (Gharibi & Seals, 2019; Montanari, Fischer, & Aceves, 2022; Nakamura, 2019; Nogueroles López, Pérez Serrano, & Duñabeitia, 2021; Rodríguez-García, Solana-Solana, Ortiz-Guitart, & Freedman, 2018; Ryan, 2023; Wan & Gao, 2021). In general, parents are interested in preserving non-majority languages, however, their opinions on the maintenance and use of certain languages differed according to several factors, such as the sociocultural background of the family (Seo, 2021), the current or imagined place of residence (Akgül, Yazıcı, & Akman, 2019; Fuentes, 2020; Kostoulas & Motsiou, 2020; Surrain & Luk, 2023) along with its sociopolitical context (Seo, 2021), or the parents’ will to actively reinforce the home language (Gharibi & Seals, 2019; Kostoulas & Motsiou, 2020), where several aspects play an important role: the parents’ personal language-learning experiences and weaknesses (Berardi-Wiltshire, 2017; Nakamura, 2019; Nogueroles et al., 2021; Ryan, 2023; Seo, 2021; Surrain & Luk, 2023), their attachment to their culture and identity (Bezcioglu-Göktolga & Yagmur, 2018; Costa-Waetzold & Melo-Pfeifer, 2020; Fuentes, 2020; Gharibi & Seals, 2019; Kostoulas & Motsiou, 2020; Kwon, 2017; Moustaoui, 2021; Ryan, 2023; Soler & Zabrodskaja, 2017; Vollmann & Soon, 2018), and the usefulness and perceived value of the language (Curdt-Christiansen & Wang, 2018; Kwon, 2017; Nandi, 2019; Seppik & Zabrodskaja, 2022; Taqavi & Rezaei, 2021; Wang, 2023).

The relation between language and identity is commonly mentioned by parents throughout studies, considering the home language a defining element of their ethnicity and culture (Berardi-Wiltshire, 2017; Lomeu Gomes, 2022; Seppik & Zabrodskaja, 2022), sometimes using spontaneous religious expressions to socialize the child into their identity and therefore, constructing a shared family identity through language (Alasmari, 2023). However, Wang (2023) considers this association to be ‘taken for granted’ (p. 10), since it is often believed that learning the heritage language automatically results in identifying with the culture.

Even though parents usually seek to maintain the heritage language and preserve their cultural legacy, sometimes they struggle to perceive it as valuable (Curdt-Christiansen, 2020; Mirvahedi, 2021; Taqavi & Rezaei, 2021). This event is observed across languages; however it appears to occur more frequently in the case of local and minority languages, especially when they consider the presence of languages of higher perceived status (Nandi, 2019; Seo, 2021). In this context, families might prioritize the development and proficiency of the majority language, so that their children can integrate in the environment, perform better at school or have a better future (Kostoulas & Motsiou, 2020; Mirvahedi & Jafari, 2021; Taqavi & Rezaei, 2021), thus, opening doors to building good career opportunities and having economic advantages (Curdt-Christiansen & Wang, 2018).

Therefore, when it comes to better adapting to different linguistic environments, having a wider range of opportunities and/or belonging to a higher social class, parents are often ready to spend more time, money and effort into helping their children learn mainstream languages such as English or Spanish (Berardi-Wiltshire, 2017; Seo, 2021; Wan & Gao, 2021) even when they are not among the linguistic repertoire of the family or the country. Parents might sometimes make this choice at the cost of losing the home language (Lee, 2021), which is tightly linked to the idea of a language hierarchy (Curdt-Christiansen & Wang, 2018). But in contrast to this idea, some parents choose to preserve and transmit their cultural and linguistic heritage to confront the accommodation to the culture of the host country and prevent the loss of their linguistic identity (Moustaoui, 2021).

Occasionally, parents are very strict with their use of the HL at home to avoid losing it to the dominant language (Wilson, 2021), however, depending on the chosen language transmission strategies, this strictness might be fruitful or lead to an alienation against the language (Nandi, 2019; Rodríguez-García et al., 2018; Seppik & Zabrodskaja, 2022; Wang, 2023; Wilson, 2021), as children also have linguistic preferences and desires that do not always need to be aligned with the parents’.

Apart from the potential opportunities that multilingualism or teaching a certain language might bring, several studies mentioned how parents assign an affective value to their languages (Berardi-Wiltshire, 2017; Curdt-Christiansen & Wang, 2018; Danjo, 2021; Kwon, 2017; Rodríguez-García et al., 2018), and prioritize transmitting their home language to build better relationships with their children (Lomeu Gomes, 2022; Wang, 2023), providing emotional support and sharing their worldviews and values, so they can later discuss life events and prevent situations that could have negative consequences (Cox et al., 2021; Cycyk & Hammer, 2020). This emotional closeness brought by maintaining the HL would act as a symbol of ‘shared identity as heritage languagespeakers’, which is essential in family cohesion (Berardi-Wiltshire, 2017) and would help the child acknowledge their own multilingual identity (Costa-Waetzold & Melo-Pfeifer, 2020; Jung, 2022; Little, 2023; Montanari et al., 2022; Rodríguez-García et al., 2018; Soler & Zabrodskaja, 2017).

There are different ways families add value to a language, shaping their beliefs, goals, and expectations (Berardi-Wiltshire, 2017), however, it is common to find families whose views and ideologies toward home-language maintenance and their actual practices do not match. On this note, several authors explain that while some parents express a will to maintain their heritage language, their practices are sometimes inclined toward supporting the societal language or a language that offers better life opportunities (Mirvahedi, 2021; Mirvahedi & Jafari, 2021), allowing them to thrive in their local context and be global citizens (Curdt-Christiansen & Wang, 2018). Another reason that could explain this mismatch between language beliefs and practices could be the challenges faced by parents when trying to maintain the minority language in a context where they might not have enough language support (Gharibi & Seals, 2019; Nakamura, 2019).

The influence of external attitudes in the use of the home languageIn some cases, the attitudes parents hold toward multilingualism and home-language maintenance, and therefore their linguistic practices, are influenced by external opinions and recommendations, which usually come from professionals that parents put their trust on, such as teachers, school headmasters or speech-language therapists (SLTs).

In other cases, those views and opinions come from friends, family members or people outside their inner circle who are not language or education professionals. Rodríguez-García et al. (2018) describe certain situations where the experiences of stigmatization that parents have received influence their decisions of not transmitting the HL to their children. Nakamura (2019) highlights ‘the power of community’, and how a supportive group reinforces parents’ practices, but that is not always the case, so implementing a multilingual approach at home might become challenging in those situations. Nonetheless, there are occasions where parents’ perspectives and language decisions are strong enough to ignore or actively disagree with people who do not share their standards or show negative attitudes toward their language ideals (Seo, 2021).

The type of advice parents receive can range from a more minority-language-friendly approach to a stronger tendency to encourage monolingualism in the majority language. Frequently, the combination of doubts parents might already have, along with the social praise of monolingualism (Fuentes, 2020) and/or the negative views of teachers and other professionals, exacerbates their concerns (Kostoulas & Motsiou, 2020) and creates a confusion that may impact parent-child interaction by reducing their home-language use in favor of the majority language (Bezcioglu-Göktolga & Yagmur, 2018). There is often a mismatch between parents’ and teachers’ attitudes and expectations toward languages (Ragnarsdóttir, 2020), which can lead to conflicts between the home and school (Bezcioglu-Göktolga & Yagmur, 2018) that might affect children's social and academic wellbeing (Curdt-Christiansen, 2020).

Language rules, regulations and laws, with the aid of the media, have the power of turning ideologies into practices, shaping the parents’ linguistic behavior at home (Mirvahedi, 2021; Mirvahedi & Jafari, 2021; Taqavi & Rezaei, 2021; Vollmann & Soon, 2018), but this is not a one-way phenomenon, since parental motivation and public opinion can also influence legislative policies and education (Montanari et al., 2022), so the family would act as a bridge between the environment and their children (Nandi, 2019). On this note, Gharibi and Seals (2019) highlight the importance of an institution that values and validates minority languages and cultures, explaining how a supportive input from the society plays an important role in building a better linguistic environment for families and their children.

The choice of different language-transmission strategies and its challengesConsidering the external and internal factors that can play a role in family language dynamics, parents make conscious or not-so-conscious decisions about the management and use of the different languages in and out of the home setting. Therefore, with the objective of preserving or reinforcing the heritage language, prioritizing the majority language, or trying to find a balance between all of them (Kostoulas & Motsiou, 2020), parents make implicit or explicit efforts to implement different language and culture-transmission policies and strategies (Fuentes, 2020; Jung, 2022; Wan & Gao, 2021) according to their priorities, which can either be planned before birth (Nakamura, 2019; Seo, 2021; Seppik & Zabrodskaja, 2022) or discussed as the child grows (Mirvahedi & Hosseini, 2023).

As mentioned before, family language policies can range from more structured and strict approaches, where the tendency is to avoid switching codes as much as possible, to more flexible methods where there is room to mix languages. In the stricter spectrum of practices, we can find policies such as One-Parent-One-Language (OPOL) (Arnaus Gil & Jiménez-Gaspar, 2022; Kostoulas & Motsiou, 2020) as well as its variant One-Language-One-Community, where one language would be spoken at home and another one in the community (Akgül et al., 2019), or the minority-language-only method (Mattheoudakis, Chatzidaki, & Maligkoudi, 2020; Nakamura, 2019; Seo, 2021). As for the flexible approaches, the concept of translanguaging arises as commonly used by families (Danjo, 2021; Jung, 2022; Little, 2023; Soler & Zabrodskaja, 2017; Wilson, 2021), conceptualized as an ad-hoc use of multiple languages instead of adhering to planned actions (Kostoulas & Motsiou, 2020), which would follow a similar line as the laissez-faire language policy, where parents allow their children to use any language when communicating with them (Gharibi & Seals, 2019). Parents also follow a situational selection of languages (Kostoulas & Motsiou, 2020) that could be placed in the middle ground, as it allows using different languages, but the use is linked to the topic, location, or situation where the interaction takes place.

In some cases, children use the target language naturally (Gharibi & Seals, 2019), but in other cases, parents need to consciously implement different strategies to prompt language acquisition and use, usually introduced through Environmental Approaches, such as spending time with the extended family (Kwon, 2017) or HL-speaking peers (Montanari et al., 2022; Nandi, 2019), maintaining contact with the home country (Berardi-Wiltshire, 2017; Gharibi & Seals, 2019; Kwon, 2017; Rodríguez-García et al., 2018), participating in playgroups (Nakamura, 2019), or engaging in language management activities such as sports teams or after-school programs (Bezcioglu-Göktolga & Yagmur, 2018; Ryan, 2023); Educational Approaches that would include enrolling their children in formal and/or non-formal HL education programs or schools (Costa-Waetzold & Melo-Pfeifer, 2020; Lee, 2021; Mattheoudakis et al., 2020; Nakamura, 2019; Nandi, 2019; Ryan, 2023; Wan & Gao, 2021; Wang, 2023), hiring private tutors or speech-language therapists (Bezcioglu-Göktolga & Yagmur, 2018; Wan & Gao, 2021); as well as other more Recreational Approaches, such as reading books, watching movies/TV or listening to music (Gharibi & Seals, 2019; Kwon, 2017; Mattheoudakis et al., 2020; Mirvahedi & Jafari, 2021; Montanari et al., 2022; Nakamura, 2019; Seppik & Zabrodskaja, 2022; Wan & Gao, 2021).

Other strategies to maintain the home language would be related to Language Awareness, including reinforcing the HL at home or everywhere, explicit translation, correcting language when requested, pretending not to understand, ignoring the child unless they use the target language, reminding their children to use the HL, not replying in the majority language, punishing or paying a fine each time the majority language is used, correcting the children's mistakes in the HL, negotiating language use with the children or insisting on the use of a certain language between siblings (Berardi-Wiltshire, 2017; Fuentes, 2020; Gharibi & Seals, 2019; Kostoulas & Motsiou, 2020; Mirvahedi & Jafari, 2021; Nakamura, 2019; Nandi, 2019; Wang, 2023; Wilson, 2021).

Nonetheless, these types of practices are not always supported, as some parents believe that forcing children to speak a certain language could be a source of anxiety and damage the bond between parent and child (Danjo, 2021; Mirvahedi & Hosseini, 2023), leading to a potential rejection of the home language (Moustaoui, 2021; Seppik & Zabrodskaja, 2022; Wilson, 2021). This perspective differs according to the person's priorities, as some parents put more emphasis on language proficiency, while others prioritize communication apart from development (Wilson, 2021). Parents believe sticking to one language and avoiding code-mixing to be the best strategy, but paradoxically, families who report following policies like OPOL often admit translanguaging, since the efforts made to separate the languages enable the presence of more than one at the same time, facilitating language mixing (Ryan, 2023).

Parents often face challenges when trying to pass on the HL while trying to find balance between languages (Fuentes, 2020; Wang, 2023), especially when the child begins their formal education (Kwon, 2017; Mirvahedi & Hosseini, 2023; Moustaoui, 2021), which is usually in the majority language, but also due to the difficulties to find a peer community nearby (Rodríguez-García et al., 2018) where they can seek for support or share similar experiences. In some cases, minority languages are not forbidden nor encouraged, but the use is reduced due to parents and/or children being aware of the social perception of the language (Curdt-Christiansen & Wang, 2018; Lomeu Gomes, 2022).

Families where children have communication disorders or disabilitiesWhen addressing the views and experiences of parents whose children have communication disorders or are labeled as disabled, it is worth noting that they share similar views with parents of children with typical development, however, there are some experiences and beliefs that are unique to families where children have communication difficulties.

One of the common perspectives shared by both types of families relate to the positive views toward multilingualism (Cioè-Peña, 2021), where parents consider the different linguistic, cognitive, social or cultural advantages that a multilingual education could bring (Howard, Gibson, & Katsos, 2021), especially in the case of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), where the flexibility associated with multilingualism is considered beneficial (Hampton, Rabagliati, Sorace, & Fletcher-Watson, 2017). It is worth noting that in this case too, parents’ attitudes are also a reflection of their personal language experiences and hopes (Howard et al., 2021).

Parents of children with communication disorders also link their language to cultural heritage and identity, aiming to transmit their customs or religious practices (Mirvahedi & Hosseini, 2023; Sher, Gibson, & Browne, 2022), having an emotional impact that allows them to maintain or reinforce parent–child bonds (Howard et al., 2021) and express affection in the home language (Hampton et al., 2017).

It is common for parents to be concerned about a multiple-language exposure delaying language development or stressing the child (Howard et al., 2021), however, in the case of families with communication difficulties, they also show concerns about multilingualism amplifying the limitations children might already have (Hampton et al., 2017), so they sometimes choose to prioritize the amelioration of the difficulties over a multilingual education by reducing the exposure to the home language and enrolling the children in monolingual schools (Cioè-Peña, 2021). Parental decisions are often based on the language abilities and the severity of symptoms of the child, however, practices may fluctuate with time (Howard et al., 2021). In this context, some families show frustration over dropping the home language, even though they often see the shift to monolingualism as the only option (Hampton et al., 2017), while others consider it a step back (Sher et al., 2022).

When it comes to perceiving children's difficulties as barriers, this view often comes from the teachers’ attitudes and the influence of other professionals (Cioè-Peña, 2021; Hampton et al., 2017; Howard et al., 2021; Mirvahedi & Hosseini, 2023; Sher et al., 2022), who often hold the narrative of multilingualism being detrimental or confusing. When parents face this situation, they sometimes take this narrative as their own and follow the advice (Cioè-Peña, 2021; Hampton et al., 2017; Mirvahedi & Hosseini, 2023), but some other times they ‘listen to their inner voice’ and continue with a multilingual upbringing (Howard et al., 2021; Mirvahedi & Hosseini, 2023). Nevertheless, as stated by Sher et al. (2022) this is not always the case, since in other occasions, practitioners agree with parents and describe the monolingual advice as ‘old-fashioned’ and ‘offensive’, considering that children with communication disorders and typically developing children should be treated equally, and encouraging parents to continue with a home-language education at home.

DiscussionThe aim of this review was to explore the available evidence addressing the perspectives and dynamics surrounding multilingualism and use of languages in families from different linguistic or cultural settings. The main focus was to study how parents perceive and value their heritage languages with the aim of showing a glimpse of how their perspectives and lived experiences may influence their linguistic dynamics and choices with their children.

The results were built around the concept of home-language maintenance and transmission, showing a clear diversity in the perspectives and experiences reported by the families from the studies, but there were also certain patterns that were recurrent across families from different nationalities.

Regarding home-language maintenance, Mattheoudakis et al. (2020) explain that a language is better preserved when parents actively get involved in its development and pay attention to its instruction. On a similar note, Arnaus Gil and Jiménez-Gaspar (2022) reported in their study that the family language policies themselves do not necessarily result on the child showing balanced language competence, however, the authors hypothesized that the combination of those language policies with the choice of the minority language as the family language might bring better outcomes. Those statements would go on the same line as what has been previously studied by other researchers such as Nieva (2015) who affirms that a multilingual environment does not necessarily guarantee a successful multilingualism on children, adding other authors (Jalil, 2011; Thordardottir, 2017) that the time of exposition, as well as the quantity, quality and type of linguistic input play a crucial role in language acquisition.

In most cases, parents showed positive attitudes toward the idea of speaking more than one language and raising multilingual children, however, as revealed in several studies, their attitudes did not always match their language choice and practices at home (Schwartz, 2008). This could be justified by the priorities of parents with regards to each aspect of their lives, where a multilingual education in the home language, albeit important, might not always be the on the top of the list, thus giving priority to the majority language or languages of higher prestige that could bring better life opportunities for their children (Curdt-Christiansen, 2009). Another possible explanation could be related to the socio-economic situation of the family and the availability of resources aimed at promoting cultural diversity in their area, creating an environment where language-learning opportunities would vary depending on the ability of parents to invest time and money on their child's education (Park & Abelmann, 2004).

No matter the parental ideologies, the results show a general agreement on the practices that would bring better results. The studies report a particular tendency to aim for the highest amount of exposure through the OPOL approach, although revealing certain controversy around the different levels of flexibility in their methods (Piller, 2001). The idea of translanguaging (Otheguy, García, & Reid, 2015) was often rejected by parents while described as inevitable by others, suggesting that the child's personality and language preferences would play a role, along with the additional challenge of separating languages or maintaining the HL once formal education begins.

But it is not only the families’ own perspectives what affect language practices and transmission. Various studies have shown how external views and attitudes – especially from professionals such as teachers or SLTs – can influence parent's decisions regarding a multilingual education and the use of the home language, where the advice received does not always go according to the preferences of the families. The studies report that professionals often discourage an education in the heritage language while supporting a switch to the majority language; a recommendation that usually comes from professional's lack of information or expertise in multilingualism (Nieva et al., 2020) and would go against the recommended practice guidelines developed by experts in the field of speech and language therapy in multilingual contexts (McLeod et al., 2013; Nieva, Aguilar-Mediavilla, et al., 2020; Stow & Pert, 2015). In addition, Rodríguez-García et al. (2018) suggested how parents’ and children's experiences regarding language use vary depending on the external perception of the home language, the person's visible ethnic features and their cultural origin. The evidence shows that when families face these situations, they often stop using their own language and switch to an education in the majority language even though they do not always master nor have the competence to provide a quality input for their children, resulting in a shared language erosion (Cox et al., 2021) that can weaken the parent-child relationship and could also impact the child's language development. The authors emphasize how maintaining the home language and having a shared identity could prevent declines in physical, mental and behavioral health, having Müller, Howard, Wilson, Gibson, and Katsos (2020) previously highlighted how a multilingual education brings not only linguistic, but social and emotional benefits for the child.

On the bright side, the results also show professionals who encourage families to maintain the home language and transmit their cultural practices to the following generations. This would align with previous research where practitioners support the use of the home language (Thordardottir & Topbaş, 2019), which suggests that professional practices in multilingual contexts may be changing. This approach would better meet parent's requirements by reducing language bias (Steinberg, Valenzuela-Araujo, Zickafoose, Kieffer, & DeCamp, 2016) and would help create a trustworthy environment, as parents often expressed an emotional attachment to their language and identity that they seek to pass on.

Additionally, this review did not exclude studies where children could have language or communication disorders as we aimed to picture the evidenced experiences of different types of multilingual families, where the management of languages in the presence of language development difficulties is another reality that we did not want to omit. It was interesting to find a similar pattern of experiences and priorities when comparing studies of families with typical development and communication disorders, such as the positive views toward multilingualism or the emotional connection to their linguistic and cultural roots (Bakić et al., 2017).

However, there were both similarities and differences in parents’ concerns and the advice received from professionals, finding recommendations of both language maintenance and withdrawal, sometimes wondering whether multilingualism would worsen the child's difficulties, which has already been proved otherwise (McLeod, Harrison, Whiteford, & Walker, 2016). These findings highlight the need for professionals to base their practices on the evidence to make informed decisions when working with multilingual children and their families, as stated by authors such as Thordardottir (2010).

Limitations and future researchIt is important to note that this study has certain limitations, such as the absence of studies with families located in Africa, even though some included people from African countries who live in Europe. Apart from that, only 5 studies addressed language perspectives and experiences in families where children had language or communication disorders, being three of them focused on autism spectrum disorder and lacking information about other conditions such as developmental language disorder or speech-sound disorders. This highlights the need to continue doing research on this matter, so there can be more information about the linguistic and cultural environments in families where children have a diverse language development.

There are some facts related to the design of the reviewed studies that the authors consider important to point out, as most of them are qualitative studies, which is not necessarily a limitation per se, but there is a scarcity of quantitative or mixed-methods studies addressing the issue. Additionally, most studies are either case studies or have a small sample size, and some of them did not specify the number of participants or focused on the authors’ own experience raising multilingual children.

The present study also presents methodological limitations related to the search process. On the one hand, using English as the language of choice for the database search might have limited the findings to articles published mostly in that language. However, even though the language bias might have compromised the access to articles, the authors reviewed papers in English, Spanish, Galician, Catalan and Portuguese, contributing to the inclusion of studies that might have had been overlooked otherwise. The authors are also aware that the search terms included in the databases might not cover all the nuances necessary to reach more relevant articles, as the term “heritage language” is missing in the database keywords but was found in several articles and later used throughout this study. In addition, the articles included were published in a specific time range to provide recent evidence addressing the research questions, however, the study would have also benefited from a wider search to provide a comparison over time.

Lastly, this review focuses on parental perspectives, but the results evidence that the chosen family language policies and strategies are not always successful as children might have other linguistic preferences, bringing up the need to study not only the views of multilingual parents, but also those of their children, allowing them to amplify their voice and counting them as independent people who have their own views and opinions. For that reason, we invite researchers to study multilingual environments considering all the members in the household.

ConclusionTo conclude, this review analyzed recent articles published between 2017 and 2023 that studied language attitudes, values and practices of multilingual families across the globe. The study reflects on the relationship between language views and actual practices in the household, considering parental and other actors’ perspectives about multilingualism. The authors included articles where there could be either presence or absence of language and/or communication disorders, finding out that there is a dearth of studies addressing this topic in the latter group, therefore calling for further studies on the matter to have a better understanding of their linguistic environments. This research would be useful for speech-language therapists and other stakeholders who work with multilinguals. The review provides an overview of the current issues surrounding language and cultural dynamics of multilingual families and encourages researchers to continue doing research from a multi-variable perspective to encompass the singularities of culturally diverse families.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestAuthors have no conflict of interest to declare.