Psychopathy is a personality disorder characterized by affective and antisocial traits. The defining features of psychopathy are risk factors to present violent behavior. It has been suggested that both orbitofrontal neuropsychological performance and genetic factors are fundamental for the development of psychopathy.

ObjectiveTo assess the moderating role of MAOA genotype on the relationship between orbitofrontal function and psychopathy traits.

Methods66 adult male inmate subjects were assessed by an executive functions battery and the MAOA-uVNTR polymorphism was obtained. Multiple regression analysis was carried out to compare the group slopes according to the genetic variation of MAOA and to assess the effect of this variation in the relationship between orbitofrontal functioning and psychopathy traits.

ResultsThe relationship between low orbitofrontal neuropsychological performance and the presence of antisocial traits of psychopathy was stronger among the low activity of MAOA allele carriers.

DiscussionThese findings were according to the previous studies about abnormal emotional processing and behavioral inhibition failures reported in subjects with genetic risk for violence, as well as with studies about neuropsychological performance in psychopaths. Further the MAOA genotype moderates the relationship between orbitofrontal functioning and antisocial traits of psychopathy which is a risk factor for violence.

La psicopatía es un trastorno de la personalidad que se caracteriza por rasgos afectivos y antisociales. Se considera que los rasgos definitorios de la psicopatía son un factor de riesgo para presentar conductas violentas. Se ha sugerido que tanto el desempeño neuropsicológico orbitofrontal como los factores genéticos son importantes para el desarrollo de la psicopatía.

ObjetivoEvaluar el efecto moderador del genotipo MAOA en la relación entre función orbitofrontal y rasgos de psicopatía.

Método66 hombres adultos de población carcelaria fueron evaluados mediante una batería de funciones ejecutivas y se obtuvo el genotipo del polimorfismo MAOA-uVNTR. Se realizó un análisis de regresión múltiple para comparar las pendientes de regresión entre los grupos divididos de acuerdo a la variación genotípica de MAOA y evaluar el efecto de dicha variación sobre la relación entre función orbitofrontal y rasgos de psicopatía.

ResultadosSe encontró que la relación entre bajo desempeño orbitofrontal y el incremento en rasgos antisociales es más fuerte en los sujetos portadores del alelo de baja actividad de MAOA.

DiscusiónEstos hallazgos se relacionan con los estudios acerca del procesamiento emocional alterado y fallas en inhibición conductual en sujetos con riesgo genético a la violencia, así como con los estudios sobre neuropsicología y psicopatía, además el genotipo MAOA modera la relación entre función orbitofrontal y rasgos antisociales de psicopatía, los cuales se consideran un factor de riesgo para la violencia.

Psychopathy is a personality disorder characterized by interpersonal, affective, behavioral and lifestyle traits such as manipulation, grandiosity, glibness, shallow affect, lack of empathy and remorse, an impulsive and irresponsible lifestyle, and the persistent violation of social norms.1 Since development and implementation of Hare's psychopathy checklist-revised (PCL-R1), the evaluation of this disorder has been improved. Psychopathy, as assessed by PCL-R, is related to interpersonal and affective personality features such as manipulation, pathological lies and lack of remorse, all together grouped in Factor 1 (F1). On the other hand the antisocial tendencies such as irresponsibility, impulsivity and criminal behavior are grouped in Factor 2 (F2).2

There is a clear relationship between psychopathy and hazardous behaviors such as violence, and it has been suggested that the deficiency of violence inhibitors such as empathy, emotional ties, low fear to punishment, egocentrism, self-justification and impulsivity facilitates the presence of violent behaviors in psychopaths.3 Also, it has been proposed that the psychopathic personality in adolescence predicts antisocial behavior, aggression and the violation of law in adulthood.4

It has been suggested that the etiology of psychopathy has an important biological component. This idea arises by studies that demonstrate the contribution of genetic factors on the development of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) that is closely related to psychopathy. In these studies genetic factors account for 50% of variance of ASPD.5–8

It has been demonstrated that genetic factors influence psychopathy traits such as antisocial behavior and detachment9; callous unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior when detachment is high10; cruelty in men with higher level of this over the time11; and cruelty, disinhibition and manipulation.12

A reason to relate genes of serotonergic system to psychopathy is the modulation of serotonin (5HT) on violence and impulsivity, namely there is a relationship between 5HT function and impulsivity in which the more impulsive offenders had more psychopathic traits.13

Monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) is an enzyme that catalyzes monoamines in brain and has affinity for 5HT. The MAOA gene is located in X chromosome (Xp11.4–Xp11.3).14 A functional polymorphism of MAOA of variable number of tandem repetitions (MAOA-uVNTR) has been described. MAOA-uVNTR is a repetition of 30 base pairs sequence in the promoter region of gene that impacts the transcription in vitro. The expression of the enzyme is relatively higher in carriers of 3.5–4 repetitions (alleles MAOAH) and lower in carriers of 2, 3, 5 repetitions (alleles MAOAL).15

Studies about molecular genetics follow the same idea about the relationship between ASPD and psychopathy, particularly MAOAL allele is associated with psychopathy traits such as violence, ASPD, aggression and impulsivity.16–23 Specific to psychopathy Fowler and colleagues24 found an association between MAOAL allele and affective traits of psychopathy.

Neuropsychological findings about psychopathy suggest a frontal dysfunction,25 specifically in ventromedial and orbitofrontal cortices26–30; on the other hand apparently the function of dorsolateral cortex is not altered.31,32 However, some ASPD traits in criminal offenders have been associated to dorsolateral dysfunction such as poor performance in planning, in addition to ventromedial dysfunction such as failure in behavioral inhibition.33

Both the MAOA u-VNTR polymorphism and psychopathy are associated to the function of prefrontal cortex; therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate if MAOA u-VNTR polymorphism moderates the relationship between executive functions and psychopathy traits in male inmates. Since psychopathy traits are related to low orbitofrontal neuropsychological performance, and MAOA genetic variation is related to impulsivity, aggression and violence, we expected an interaction between MAOA genotype and neuropsychological performance in orbitofrontal/ventromedial related tasks to predict Factor 2 score. On the other hand, due to previous findings about the relationship between dorsolateral function and ASPD traits we were interested in investigating the effect of dorsolateral neuropsychological performance on psychopathy factors.

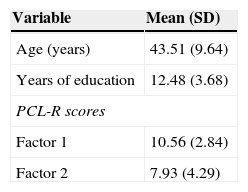

MethodsParticipantsA total of 66 male inmates from high-security prisons in Mexico participated in this study. The mean age, mean years of education, mean PCL-R factor scores and distribution of MAOA alleles are shown in Table 1. The sample selection was conducted by reviewing case files. Inclusion criteria were being Mexicans of Mexican ancestry to avoid stratification artifacts, the absence of any psychiatric, medical or neurological disorder, visual or auditory illness, severe traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness, drug consumption in the last 6 months. Each participant signed a written consent.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample.

| Variable | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.51 (9.64) |

| Years of education | 12.48 (3.68) |

| PCL-R scores | |

| Factor 1 | 10.56 (2.84) |

| Factor 2 | 7.93 (4.29) |

| MAOA alleles | Count (%) |

|---|---|

| MAOAH | 42 (64) |

| MAOAL | 24 (36) |

PCL-R: Hare's psychopathy check list-revised; MAOAH: high activity of MAOA; MAOAL: low activity of MAOA.

DNA was collected from buccal cell samples using the Gentra Puregen Buccal Cell Kit (Qiagen). The analysis of MAOA u-VNTR polymorphism was made through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using standard methods. The oligonucleotides sequence was, sense orientation: 5′-ACA GCC TGA CCG TGG AGA AG-3′, antisense orientation: 5′-GAA CGG ACG ACG CTC CAT TCG GA-3′. The PCR was made in a final volume of 12.5μl containing 1.5mM of MgCl2, 200μM of each oligonucleotide, 0.2μM of dNTPs (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP), 0.25U of Go Taq Flexi of promega and 50ng of genomic DNA. After 4min of denaturation at 95°C, 35 cycles with the following specifications were performed: 1min at 95°C, 1min at 62°C, 1min at 72°C and finally 4min at 72°C. The PCR products were analyzed by means of electrophoresis in agarose/Metaphor gels at 2.5% and visualized with UV light after staining with ethidium bromide. The subjects were grouped according to their MAOA genotype. The distribution of the alleles was 64% carriers of MAOAH allele, and 36% carriers of MAOAL allele (see Table 1).

Psychopathy assessmentTo determine the psychopathy level of the inmates a semistructured interview adapted from Hare's interview to detect psychopathy was used.1 It focused on family history, education, personal relationships, work history, juvenile delinquency, criminal career and other psychopathic traits. Also a detailed review of files provided by the prison authorities was carried out.

Psychopathy was assessed by two different raters independently using the standardized version in Mexican inmate population of PCL-R34; this is a 20-item, three point scale (0–2); total score can range from 0 to 40 and reflect the degree to which the person matches the psychopathy construct. Items can be arranged in a two-factor structure. Factor 1 (F1) reflects the core personality features of psychopathy, while Factor 2 (F2) reflects a socially deviant lifestyle and antisocial behaviors. The inter-rater score of 0.90 was obtained for the total PCL-R score, 0.91 for F1 and 0.89 for F2.

Neuropsychological assessmentThe performance in orbitofrontal/ventromedial and dorsolateral related tasks was assessed using Executive Functions Battery BANFE.35 This is comprised of 15 subtests that assess frontal and executive functions related to orbitofrontal, dorsolateral and anterior cortices. In this study only the orbitofrontal index (OFI) and the dorsolateral index (DLI) were used. OFI measures inhibitory control, incorporation of social rules, and following up of instructions as well as risk/benefit processing. The DLI measures visuospatial and verbal working memory, mental flexibility, verbal fluency and planning. Performance in each index is based on a mean of 100 (SD=15).

ProcedureThe protocol was approved by the prison authorities; it consisted of three sessions of 2.5h each. Before the first session, criminological case files were reviewed in order to select the sample.

During the first session a semistructured interview and clinical history were carried out. During the second and third sessions the BANFE was applied and DNA was collected.

Statistical analysisMultiple linear regression analyses were conducted to test for the effect of five independent variables (MAOA u-VNTR, OFI, DLI) and interaction terms (MAOA u-VNTR*OFI, MAOA u-VNTR*DLI) to predict F1 and F2 scores of PCL-R. Due to statistical artifacts a hierarchical approach was adopted, namely, the principal effects of genotype, OFI and DLI were entered first in a regression model, and then the interaction terms were included.

All analyses were conducted using JMP software v10 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Due to the small effect of a single gene variation on behavioral measures the statistical significance was set at 0.05.

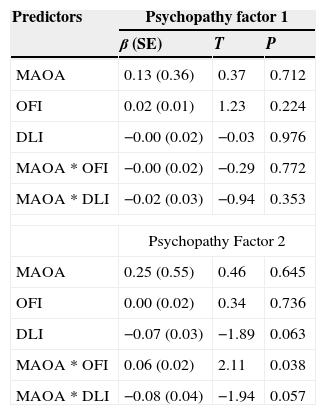

ResultsEffect of MAOA genotype and executive functions performance on psychopathy traitsThe principal effects of MAOA-uVNTR polymorphism, Orbitofrontal and Dorsolateral neuropsychological performance on both psychopathy factors are shown in Table 2.

Relationship of neuropsychological performance and MAOA genotype on psychopathy traits.

| Predictors | Psychopathy factor 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | T | P | |

| MAOA | 0.13 (0.36) | 0.37 | 0.712 |

| OFI | 0.02 (0.01) | 1.23 | 0.224 |

| DLI | −0.00 (0.02) | −0.03 | 0.976 |

| MAOA*OFI | −0.00 (0.02) | −0.29 | 0.772 |

| MAOA*DLI | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.94 | 0.353 |

| Psychopathy Factor 2 | |||

| MAOA | 0.25 (0.55) | 0.46 | 0.645 |

| OFI | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.34 | 0.736 |

| DLI | −0.07 (0.03) | −1.89 | 0.063 |

| MAOA*OFI | 0.06 (0.02) | 2.11 | 0.038 |

| MAOA*DLI | −0.08 (0.04) | −1.94 | 0.057 |

OFI=orbitofrontal index; DLI=dorsolateral index; β=regression coefficient; SE=standard error.

The results of multiple regression analysis shown that genotype and neuropsychological performance (orbitofrontal and dorsolateral) were not associated with both psychopathy factors.

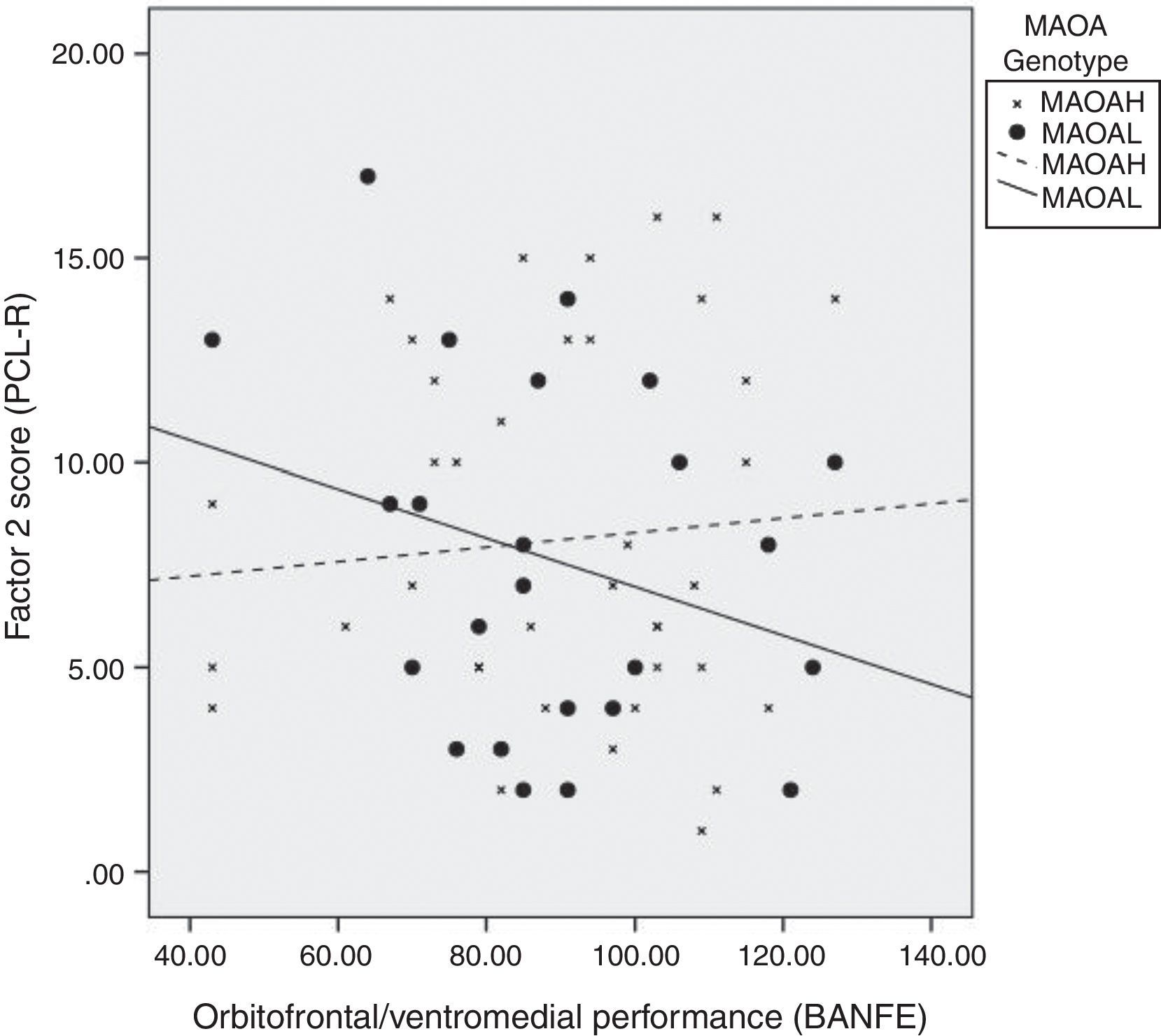

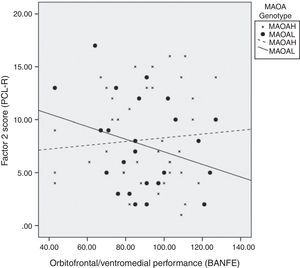

Interaction of MAOA-uVNTR and neuropsychological performance (orbitofrontal and dorsolateral) on psychopathy traitsA significant interaction effect between MAOA-uVNTR polymorphism and orbitofrontal neuropsychological performance was found on Factor 2 of psychopathy (β=−0.06, P=0.038) (see Table 2) (Fig. 1).

Scatterplot of orbitofrontal/ventromedial performance vs. factor 2 score; crosses represent the dispersion of MAOAH allele carriers, dots represent the dispersion of MAOAL allele carriers; dashed line represent the slope of MAOAH allele carriers, continuous line represent the slope of MAOAL allele carriers.

The main finding in the present study was the interaction between MAOA-uVNTR polymorphism and neuropsychological performance in executive functions, particularly the orbitofrontal/ventromedial performance. This interaction implies that the natural variation of the MAOA gene moderates or modifies the association between orbitofrontal functioning and antisocial and lifestyle features grouped in Factor 2 of psychopathy, namely, decrements in orbitofrontal neuropsychological performance are associated with increments in Factor 2 scores (antisocial and lifestyle features). This association was most evident in MAOAL allele carriers.

There is a strong relationship between psychopathy and violence, the lack of violence inhibitors such as empathy, having emotional ties with others, reduced fear to punishment, and the presence of egocentrism, self-justification and impulsivity, enhancing the presence of violent behavior in psychopaths.3 However not all features of psychopathy (measured by PCL-R) are related with violent behavior. The results of two meta-analysis showed that Factor 2 had a better efficacy to significantly predict violent behavior (effect size range: 0.4–0.6) than Factor 1 (effect size range: 0.1–0.2),36,37 that implies that increments in Factor 2 scores are associated with high risk to commit violent acts.

The MAOAL carriers showed a strong association between low orbitofrontal performance and high Factor 2 scores. It has been proposed that the low activity allele is associated with increments in features related to violent behavior such as presence of ASPD, emotional disturbances, impulsivity, physical aggression, weapon use and gang membership,16–23 so the low activity allele confers vulnerability to violent behavior. There is strong evidence derived from fMRI's studies that this vulnerability could be due to the tendency to experience negative emotions since MAOAL carriers show hyperactivity in emotion-related cerebral structures in response to negative emotional tasks,38–40 and at behavioral level the MAOAL carriers show increments in personal distress and impulsivity measures.41 In this sense some structural MRI studies revealed that healthy MAOAL carriers (compared to MAOAH carriers) show differences in gray matter concentration on the orbitofrontal area of frontal-inferior gyrus.40,42 The activity of this cerebral region has been differentially related to negative affectivity and the tendency to inhibit the expression of emotion or behavior in social relationships, or social inhibition, namely negative affectivity was negative correlated, while social inhibition was positively correlated.43 Considering this structural and functional evidence is likely that MAOAL carriers have a neurobiological predisposition to experience negative emotions and tend to fail to inhibit their behavior and as a result may present an increase in behaviors grouped in Factor 2 of psychopathy such as impulsivity and antisocial behaviors.

Another finding in the present study was the lack of effect of dorsolateral performance on both psychopathy factors, despite the evidence which suggested that dorsolateral executive functions such as planning are altered in APSD subjects.33 Our results are according to the previously studies that emphasize the orbitofrontal dysfunction in psychopaths that reflects failures in modulation of dominant responses that is related to higher levels of aggression and impulsivity.26–32

Research conducted with inmates entails ethical considerations. From the genetic perspective the use of genetic markers that confer risk for the development of personality disorders could be included as a complement for diagnosis thus the behavioral traits of psychopathy (e.g. failure to conform to social norms, violence) can be addressed as a clinical entity and as a result develop therapeutic strategies considering the socio-emotional dysfunction associated to MAOA-uVNTR polymorphism.

The present study has some limitations to be considered. The sample size was small to detect an association between MAOA genotype, and thus in future studies it is necessary to increase the sample size. Similarly the results should be viewed cautiously since the interaction term MAOA*OFI was barely significant, perhaps due to sample size. On the other hand, the present study has some strengths. First the statistical analysis allowed to explore the effect of orbitofrontal performance on psychopathy factors controlling potential confounding effects such as the relationship with dorsolateral performance. Despite the sample being composed of inmates the inclusion criteria allowed to explore the specific effects of independent variables on psychopathy traits controlling variables such as substance abuse, or neurological and psychiatric background; also the neuropsychological indexes (orbitofrontal, dorsolateral) allowed to explore the whole function of these prefrontal areas instead of measuring isolated functions.

ConclusionsThe present findings suggest that the genetic variation of MAOA impacts the relationship between low orbitofrontal/ventromedial functions and high antisocial traits measured by PCL-R. Despite this moderating role of the MAOA genotype is important to consider that the construct of psychopathy also includes affective traits. Therefore it is necessary to carry out studies about the genetic contribution on these affective traits and its relationship to neurocognitive bio-markers to have a better understanding of this complex phenotype.

FundingThis work was partially supported by PAPIIT IN305313: “Conducta violenta y sus bases biológicas: neuroimagen, neuropsicología y electrofisiología”.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

To Dr. Beatriz Camarena-Medellín for the genotyping analysis.