Inventorying biodiversity is basic for conservation and natural resources management because constant loss of natural areas increases the need for fast biodiversity inventories. Desert flea diversity and associations are not well known in Mexican deserts, especially in the Oriental Basin (OB). Rodents were trapped in the Oriental Basin through June 2007, 2009, and 2010, and July 2008, in 10 localities. A total of 144 rodents belonging to 10 species were trapped, of which 133 were parasitized by 350 fleas belonging to 18 species. Peromyscus difficilis had the highest parasite richness with 9 species, followed by P. maniculatus with 8. The most abundant fleas in the OB were Polygenis vazquezi, Plusaetis parus, Meringis altipecten, and Plusaetis mathesoni. Seven species were found representing new records for 3 states.

Tener un inventario de la diversidad biológica es fundamental para la conservación y gestión de los recursos naturales, ya que la pérdida constante de áreas naturales aumenta la necesidad de realizar inventarios rápidos de la biodiversidad. En particular la diversidad de pulgas y sus asociaciones no son muy conocidas en zonas áridas de los desiertos mexicanos, especialmente en la Cuenca Oriental. Por lo anterior, fueron colectados roedores en 10 localidades de la Cuenca Oriental en junio de 2007, 2009, 2010 y julio de 2008. Se recolectó un total de 144 roedores pertenecientes a 10 especies; 133 estaban parasitados por 350 pulgas pertenecientes a 18 especies. Peromyscus difficilis tuvo la riqueza más alta de pulgas con 9 especies, seguido por P. maniculatus con 8. Las pulgas más abundantes en la Cuenca Oriental fueron Polygenis vazquezi, Plusaetis parus, Meringis altipecten y Plusaetis mathesoni. Se encontraron 7 especies que representan nuevos registros para 3 estados.

Inventorying biological diversity is a basic scientific activity, essential for good conservation practices and natural resources management. Financial resources and human efforts dedicated to document biodiversity of a given area ideally promote better conservation activities and policies (Brooks, da Fonseca, & Rodrigues, 2004a, 2004b; Ferrier et al., 2004). Constant loss of natural areas located near cities and drastic changes in land use increase the need for fast biodiversity inventories. An area located in Central Mexico that may vanish in the short term is the Oriental Basin (OB; Hafner & Riddle, 2005).

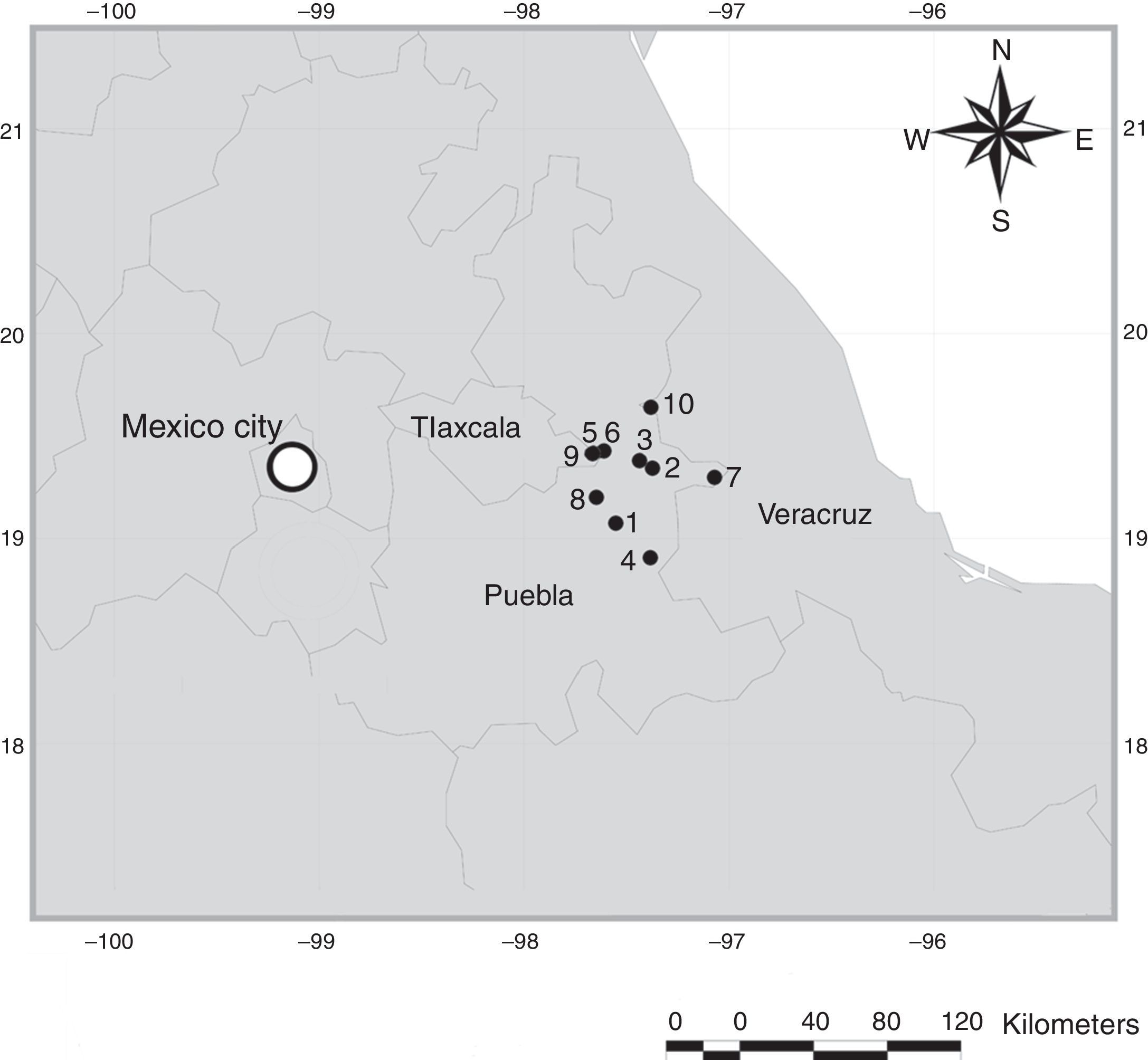

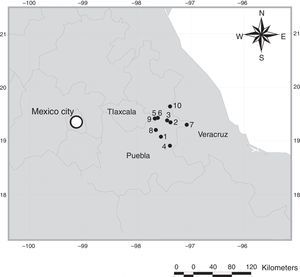

This region is considered a relict of the Chihuahuan desert and its southern-most extension (Shreve, 1942; Fig. 1). The vegetation is characterized by alkaline grass and thorn scrub in the dry valleys, and coniferous forest in the surrounding mountains (Valdéz & Ceballos, 1997). The OB area has been isolated at least since Pleistocene times, and several endemic mammals can be found here: Cratogeomys fulvescens Merriam, 1895 (Hafner et al., 2005), Peromyscus bullatus Osgood, 1904 (González-Ruíz & Álvarez-Castañeda, 2005), Neotoma nelsoni Goldman, 1905 (Fernández, 2012; González-Ruíz, Ramírez-Pulido, & Genoways, 2006), and Xerospermophilus spilosoma perotensis (Bennett, 1833) (Best and Ceballos, 1995; Fernández, 2012).

Map of localities in the Oriental Basin in Central Mexico. 1, Chalchicomula de Serna, 3km S Cd. Serdán entronque Cd. Serdán – Esperanza, Dirección Santa Catarina; 2, Guadalupe Victoria, 2km W Guadalupe Victoria; 3, Guadalupe Victoria, 9.6km W Guadalupe Victoria; 4, La Esperanza, 2km W La Esperanza; 5, Oriental, 1km S Oriental; 6, Oriental, 1.5km S Oriental; 7, Quimixtlan, 10km NE Huaxcaleca; 8, San Salvador El Seco, 1km S Coyotepec; 9, El Carmen Tequexquitla, 2.5km El Carmen; 10, Perote, 3km S El Frijol Colorado.

Interspecific interactions such as parasitism are considered an important part of biodiversity (Wilson, 1992). Some of the most common mammal parasites are fleas (Insecta: Siphonaptera). Siphonapterans are characterized by the lack of wings, and a buccal apparatus adapted for biting and sucking blood. Their body is small (1–9mm) and laterally compressed, with strong legs and big coxae (Barrera, 1953; Rothschild, 1975).

Fleas are bird and mammal parasites. However, bird fleas represent only 5% of the known flea diversity. Most of the flea species have been found in mammals, and 70% of all fleas have been collected in rodents (Traub, Rothschild, & Haddow, 1983). Usually, when their host dies, fleas leave the body and look for a new host. Many flea species are apparently host specific, whereas others lack a close relationship with a specific host and are able to parasitize several mammal species (Barrera, 1953; Whitaker & Morales-Malacara, 2005).

Parasite conservation may not be a popular topic, but preserving and studying parasite diversity and interactions represent many benefits. Christe, Michaux, and Morand (2006) point out that parasites must be preserved not only for being part of biodiversity, but also for actively modeling community structure and keeping diversity, for being good indicators of ecosystem health by accumulating heavy metals in their tissues, for their use in biomedicine, and because their DNA may provide a biological record of evolutionary dynamics between parasites and hosts.

In Mexico, 163 flea species have been recorded (Salceda-Sánchez & Hastriter, 2006), and recent work raised the number to 172 (Acosta, 2014). However, flea species diversity in Mexico is probably higher, because many large areas like desert regions lack extensive flea inventories and show only scattered records (Gutiérrez-Velázquez, Acosta, & Ortiz, 2006; Ponce & Llorente, 1996; Salceda-Sánchez & Hastriter, 2006).

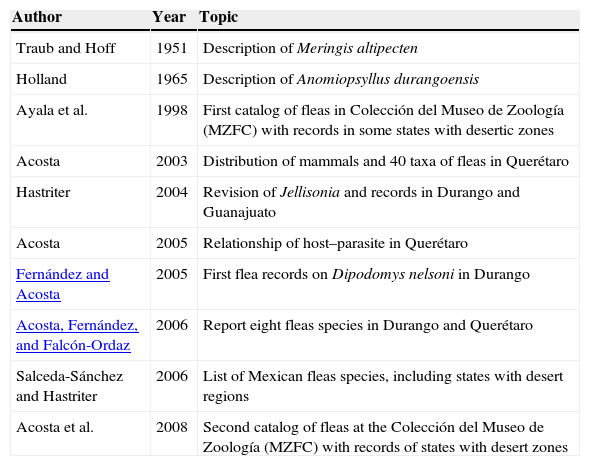

Arid land studies on Mexican fleas are not abundant, but some of them have documented new species, generated regional checklists, distributional records, taxonomic revisions, and explored co-distributional aspects (Table 1). Only 2 recent publications exist for the study area: Acosta, Fernández, Llorente, and Jimenéz (2008) presented data for 6 and 5 flea species in El Carmen Tequexquitla (Tlaxcala) and La Esperanza (Puebla), respectively; and Falcón-Ordaz, Acosta, Fernández, and Lira-Guerrero (2012) documented ecto- and endo-parasites of 5 rodent species in the OB.

Author, year, and main topic of bibliographic references regarding arid land studies on Mexican fleas.

| Author | Year | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Traub and Hoff | 1951 | Description of Meringis altipecten |

| Holland | 1965 | Description of Anomiopsyllus durangoensis |

| Ayala et al. | 1998 | First catalog of fleas in Colección del Museo de Zoología (MZFC) with records in some states with desertic zones |

| Acosta | 2003 | Distribution of mammals and 40 taxa of fleas in Querétaro |

| Hastriter | 2004 | Revision of Jellisonia and records in Durango and Guanajuato |

| Acosta | 2005 | Relationship of host–parasite in Querétaro |

| Fernández and Acosta | 2005 | First flea records on Dipodomys nelsoni in Durango |

| Acosta, Fernández, and Falcón-Ordaz | 2006 | Report eight fleas species in Durango and Querétaro |

| Salceda-Sánchez and Hastriter | 2006 | List of Mexican fleas species, including states with desert regions |

| Acosta et al. | 2008 | Second catalog of fleas at the Colección del Museo de Zoología (MZFC) with records of states with desert zones |

The objective of this work was to increase the existing inventory of fleas and rodents in the OB. Based on the specimens collected, mean abundance and prevalence of fleas species were calculated; likewise, their associations with rodent species were analyzed. Furthermore, habitat and host preferences, and host and parasite diversity, were also discussed.

Materials and methodsThe OB is an arid or semi-arid region located among the southeastern mountains of the Trans-Mexico Volcanic Axis (TMVA; Fig. 1), between 19°42′00″ and 18°57′00″N, 98°02′24″ and 97°09′00″W. The OB is shared among the states of Puebla, Tlaxcala, and Veracruz, and is a relatively small area (5,000km2 approximately) characterized by grassland, alkaline grassland, thorn scrub and corn fields (Valdéz & Ceballos, 1997).

Rodent sampling was carried out during June 2007, 2009, and 2010, and during July 2008, in 10 localities (Fig. 1; Table 2). Rodents were taken with collecting permits FAUT-0002 and FAUT-0219 granted to F. A. Cervantes and J. J. Morrone, respectively. Mammal specimens were housed at Colección Nacional de Mamíferos (CNMA), Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and at the Museum of Natural Science (LSUMZ), Louisiana State University. The collected fleas were housed at Colección de Siphonaptera “Alfonso L. Herrera”, Museo de Zoología (MZFC), Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM.

States, sampling localities, vegetation, elevation, and geographic coordinates of sampling areas in the Oriental Basin (OB), Mexico.

| State | Localities | Vegetation | Altitude | Geographic coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puebla | Chalchicomula de Serna, 3km S Cd. Serdán junction Cd. Serdán – Esperanza, direction Santa Catarina | Desert scrub | 8,320ft | 19°00′32.5″N, 97°33′21.3″W |

| Guadalupe Victoria, 2km W Guadalupe Victoria. | Crop/farming – sandy soil | 7,893ft | 19°16′49.7″N, 97°22′41.4″W | |

| Guadalupe Victoria, 9.6km W Guadalupe Victoria. | Crop/farming – sandy soil | 7,874ft | 19°18′56.8″N, 97°25′58.4″W | |

| La Esperanza, 2km W La Esperanza | Crop/farming – Agave fields | 8,349ft | 18°50′31.0″N, 97°23′09.1″W | |

| Oriental, 1km S Oriental | Desert scrub | 7,742ft | 19°21′10″N, 97°38′07.8″W | |

| Oriental, 1.5km S Oriental. | Desert scrub | 7,742ft | 19°21′10″N, 97°38′07.8″W | |

| Quimixtlan, 10km NE Huaxcaleca. | 19°13′59″N, 94°4′46″W | |||

| San Salvador El Seco, 1km S Coyotepec | Desert scrub | 7,988ft | 19°00′32.5″N, 97°33′21.3″W | |

| Tlaxcala | El Carmen Tequexquitla, 2.5km El Carmen. | Desert scrub | 7,801ft | 19°21′00.4″N, 97°39′54.5″W |

| Veracruz | Perote, 3km S El Frijol Colorado | Crop/farming | 7,988ft | 19°34′20.4″N, 97°23′00.7″W |

Rodents were trapped using standard methods approved by the American Society of Mammalogists (Kelt, Hafner, & The American Society of Mammalogists’ ad hoc Committee for guidelines on handling rodents in the field, 2010; Sikes, Gannon, & the Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists, 2011). Sherman traps were baited with oatmeal, and captured rodents were identified in the field or at the laboratory using taxonomic keys (Hall, 1981).

Fleas were collected by brushing every rodent with a toothbrush, and they were subsequently placed in vials filled with 80% ethanol. Siphonapterans were mounted on slides following Smit (1957). Fleas were determined to species level using taxonomic keys by Acosta and Morrone (2003), Barnes, Tipton, and Wildie (1977), Hastriter (2004), Hopkins and Rothschild (1956, 1962, 1966), Linardi and Guimarães (2000), Stark (1958), Traub (1950), and Traub et al. (1983). For each host species the following indices and parameters were calculated: flea species richness (S=number of species), mean abundance (MA=total number of individuals of a parasite species on a host/total number of species, including infested and non-infested species), and prevalence ([P=number of infested animals with 1 or more individuals of a parasite species/total number of examined mammals for that parasite species]*100). The Shannon–Wiener diversity index (H=−∑[pilnpi]) was also calculated for hosts and parasites (Begon, Harper, & Townsend, 1988; Bush, Lafferty, Lotz, & Shostak, 1997).

ResultsA total of 144 rodents belonging to 10 species (H=1.450), 4 families (Muridae, Heteromyidae, Sciuridae and Geomyidae), and 6 genera were recorded, of which 133 were parasitized by 350 fleas belonging to S=18 species (H=1.860), 11 genera, and 4 families (Pulicidae, Rhopalopsyllidae, Ctenophthalmidae, and Ceratophyllidae).

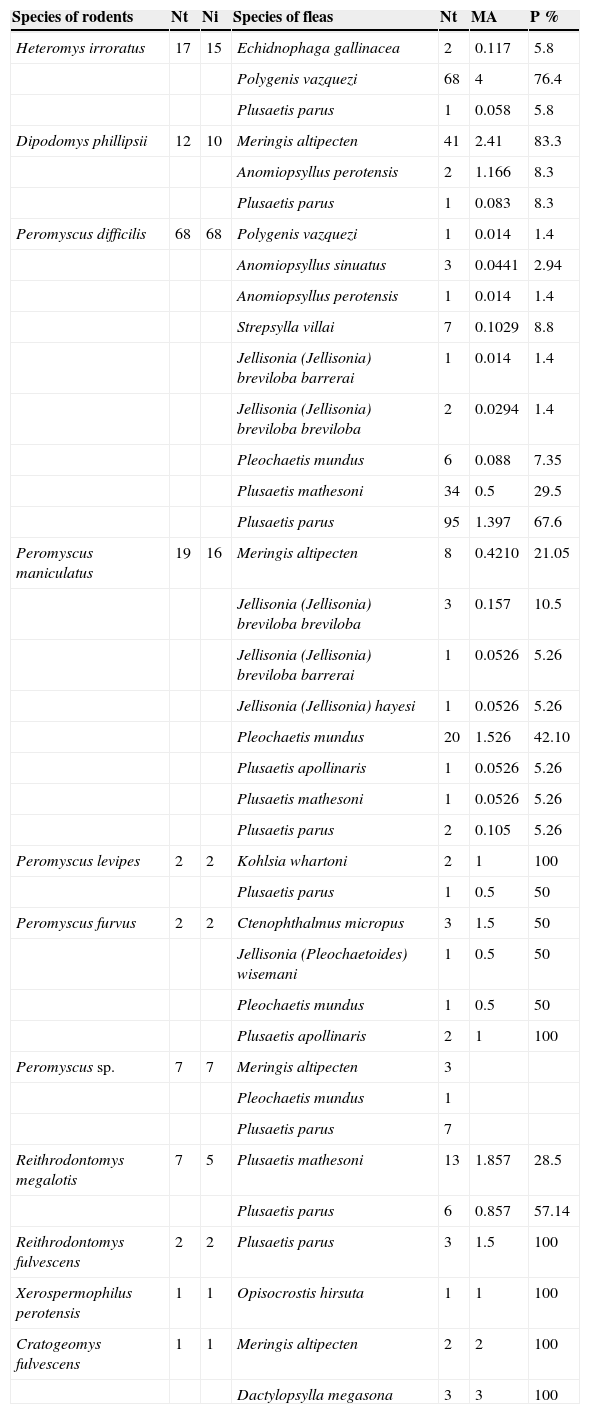

Peromyscus difficilis (J. A. Allen, 1891) had the highest parasite richness of S=9, followed by P. maniculatus (Wagner, 1845) with S=8 species. The rodent species with the smallest number of fleas were the fulvous harvest mouse Reithrodontomys fulvescens J. A. Allen, 1894 and the Perote ground squirrel Xerospermophilus spilosoma perotensis with only 1 species each (Table 1).

The most abundant fleas in the OB were Polygenis vazquezi Vargas, 1951, Plusaetis parus (Traub, 1950), Meringis altipectenTraub and Hoff, 1951, and Plusaetis mathesoni (Traub, 1950;Table 3). Differences were found in flea prevalence on rodent species (Table 3). Meringis altipecten (83.3%) on Phillips’ kangaroo rat Dipodomys phillipsii Gray, 1841, P. vazquezi on the Mexican spiny pocket mouse Heteromys irroratus (Gray, 1868) (76.4%), and P. parus (67.6%) on the rock mouse Peromyscus difficilis, show the highest rodent-specific prevalence values, above 50% of prevalence (some species have values of 100% but these were not taken into account by the sample size). The total prevalence value for the OB was 92.3%, meaning that most rodent species harbor at least 1 species of flea. The largest overall prevalence values in fleas in the OB were P. parus (42.36%), P. mathesoni (16.6%), P. mundus (Jordan and Rothschild, 1922) (12.5%), and M. altipecten (11.8%) (Table 4), besides being shared species in 3 states, on the other hand, smallest prevalence values for fleas were Opisocrostis hirsuta Jordan, 1933, Dactylopsylla megasona, Jellisonia (Jellisonia) hayesiTraub, 1950, and Echidnophaga gallinacea (Westwood, 1875), with a value of 0.69% in each case.

Fleas from rodent species in the OB, Mexico (Nt=number of total individuals, Ni=number of infested individuals, MA=abundance, P=prevalence %).

| Species of rodents | Nt | Ni | Species of fleas | Nt | MA | P % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heteromys irroratus | 17 | 15 | Echidnophaga gallinacea | 2 | 0.117 | 5.8 |

| Polygenis vazquezi | 68 | 4 | 76.4 | |||

| Plusaetis parus | 1 | 0.058 | 5.8 | |||

| Dipodomys phillipsii | 12 | 10 | Meringis altipecten | 41 | 2.41 | 83.3 |

| Anomiopsyllus perotensis | 2 | 1.166 | 8.3 | |||

| Plusaetis parus | 1 | 0.083 | 8.3 | |||

| Peromyscus difficilis | 68 | 68 | Polygenis vazquezi | 1 | 0.014 | 1.4 |

| Anomiopsyllus sinuatus | 3 | 0.0441 | 2.94 | |||

| Anomiopsyllus perotensis | 1 | 0.014 | 1.4 | |||

| Strepsylla villai | 7 | 0.1029 | 8.8 | |||

| Jellisonia (Jellisonia) breviloba barrerai | 1 | 0.014 | 1.4 | |||

| Jellisonia (Jellisonia) breviloba breviloba | 2 | 0.0294 | 1.4 | |||

| Pleochaetis mundus | 6 | 0.088 | 7.35 | |||

| Plusaetis mathesoni | 34 | 0.5 | 29.5 | |||

| Plusaetis parus | 95 | 1.397 | 67.6 | |||

| Peromyscus maniculatus | 19 | 16 | Meringis altipecten | 8 | 0.4210 | 21.05 |

| Jellisonia (Jellisonia) breviloba breviloba | 3 | 0.157 | 10.5 | |||

| Jellisonia (Jellisonia) breviloba barrerai | 1 | 0.0526 | 5.26 | |||

| Jellisonia (Jellisonia) hayesi | 1 | 0.0526 | 5.26 | |||

| Pleochaetis mundus | 20 | 1.526 | 42.10 | |||

| Plusaetis apollinaris | 1 | 0.0526 | 5.26 | |||

| Plusaetis mathesoni | 1 | 0.0526 | 5.26 | |||

| Plusaetis parus | 2 | 0.105 | 5.26 | |||

| Peromyscus levipes | 2 | 2 | Kohlsia whartoni | 2 | 1 | 100 |

| Plusaetis parus | 1 | 0.5 | 50 | |||

| Peromyscus furvus | 2 | 2 | Ctenophthalmus micropus | 3 | 1.5 | 50 |

| Jellisonia (Pleochaetoides) wisemani | 1 | 0.5 | 50 | |||

| Pleochaetis mundus | 1 | 0.5 | 50 | |||

| Plusaetis apollinaris | 2 | 1 | 100 | |||

| Peromyscus sp. | 7 | 7 | Meringis altipecten | 3 | ||

| Pleochaetis mundus | 1 | |||||

| Plusaetis parus | 7 | |||||

| Reithrodontomys megalotis | 7 | 5 | Plusaetis mathesoni | 13 | 1.857 | 28.5 |

| Plusaetis parus | 6 | 0.857 | 57.14 | |||

| Reithrodontomys fulvescens | 2 | 2 | Plusaetis parus | 3 | 1.5 | 100 |

| Xerospermophilus perotensis | 1 | 1 | Opisocrostis hirsuta | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| Cratogeomys fulvescens | 1 | 1 | Meringis altipecten | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| Dactylopsylla megasona | 3 | 3 | 100 |

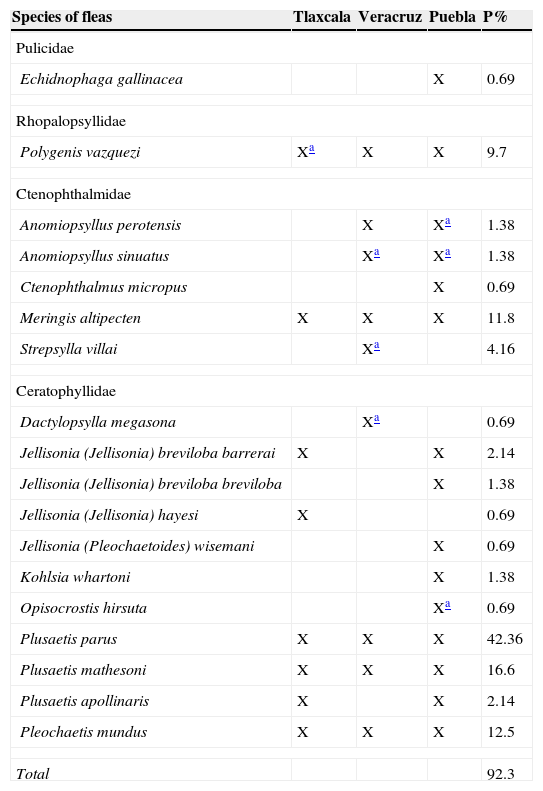

Fleas species collected in the Oriental Basin, Central Mexico.

| Species of fleas | Tlaxcala | Veracruz | Puebla | P% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulicidae | ||||

| Echidnophaga gallinacea | X | 0.69 | ||

| Rhopalopsyllidae | ||||

| Polygenis vazquezi | Xa | X | X | 9.7 |

| Ctenophthalmidae | ||||

| Anomiopsyllus perotensis | X | Xa | 1.38 | |

| Anomiopsyllus sinuatus | Xa | Xa | 1.38 | |

| Ctenophthalmus micropus | X | 0.69 | ||

| Meringis altipecten | X | X | X | 11.8 |

| Strepsylla villai | Xa | 4.16 | ||

| Ceratophyllidae | ||||

| Dactylopsylla megasona | Xa | 0.69 | ||

| Jellisonia (Jellisonia) breviloba barrerai | X | X | 2.14 | |

| Jellisonia (Jellisonia) breviloba breviloba | X | 1.38 | ||

| Jellisonia (Jellisonia) hayesi | X | 0.69 | ||

| Jellisonia (Pleochaetoides) wisemani | X | 0.69 | ||

| Kohlsia whartoni | X | 1.38 | ||

| Opisocrostis hirsuta | Xa | 0.69 | ||

| Plusaetis parus | X | X | X | 42.36 |

| Plusaetis mathesoni | X | X | X | 16.6 |

| Plusaetis apollinaris | X | X | 2.14 | |

| Pleochaetis mundus | X | X | X | 12.5 |

| Total | 92.3 | |||

P=prevalence %.

The fleas that were found on most of the hosts were: Plusaetis parus on 7 rodent species (Table 3), followed by P. mundus on 4 species, P. mathesoni, and M. altipecten on 3 species, respectively.

In the OB, 7 species were found representing new records for 3 states, Tlaxcala (1 species), Puebla (3), and Veracruz (3; Table 4).

DiscussionThis is one of the first studies on basic parasite ecology in the OB. Previous works in the OB (Acosta & Fernández, 2009; Falcón-Ordaz et al., 2012) reported 11 flea species on 6 rodent species. Here we duplicated host and parasite numbers by visiting more localities, allowing us to have a greater representation of species and a better understanding of interactions inside rodent and parasite communities.

For this work, only the dry valleys of the OB were sampled. However, this area shows habitat variety such as small hills alternated with plains covered by native vegetation or agriculture fields (Valdéz & Ceballos, 1997). This habitat mosaic allows several rodent species and other mammals to live there, as well as their ectoparasites. Flea and rodent diversity was low with values below 2 (Begon et al., 1988).

However, Lareschi, Ojeda, and Linardi (2004) in a desert biome in Argentina, obtained similar values and reported that the diversity of fleas is high. Here we can consider that diversity was higher in fleas than in rodents, probably because fleas are more abundant and diverse in small and medium sized mammals (Krasnov, Shenbrot, Medvedev, Vatschenok, & Khokhlova, 1997), and/or because most fleas are generalists, meaning that 1 flea species may parasitize more than 1 host species (Marshall, 1981; Traub, 1985). Additionally, flea diversity in an area is not determined only by host species, but by environmental parameters inherent to the habitat, that will determine nest and den conditions (temperature, humidity, and construction material; Krasnov et al., 1997). All these characteristics will complete basic flea needs like food, habitat and mating opportunities (Marshall, 1981), favoring flea species and population abundance.

Total flea prevalence for the OB is >90% for rodents, but fleas with the highest prevalence were Plusaetis parus, P. mathesoni, M. altipecten, and Polygenis vazquezi. The first one was found in more than 40% of the rodents collected in the OB. Fleas of the genus Plusaetis are very diverse in Mexico, and very abundant (Ponce & Llorente, 1996) in central and southern parts of the country.

Most of the flea species collected here were previously found in the states forming the OB (Tlaxcala, Puebla, or Veracruz; Acosta et al., 2008; Acosta & Fernández, 2009; Ayala-Barajas, Morales, Wilson, Llorente, & Ponce, 1988; Table 4), but some of the species reported here are new records for Tlaxcala (Polygenis vazquezi), Puebla (Anomiopsyllus perotensisAcosta and Fernández, 2009, A. sinuatusHolland, 1965, and Opisocrostis hirsuta Baker, 1895), and Veracruz (Strepsylla villai Traub and Barrera, 1955, A. sinuatus, Dactylopsylla megasona, and O. hirsuta).

The record of Opisocrostis hirsuta is relevant because it is the first siphonapteran collected on the OB endemic Xerospermophilus spilosoma perotensis (the Perote ground squirrel). Hall and Dalquest (1963) collected flea specimens from this species, but they did not publish their findings. According to Best and Ceballos (1995) there are no ectoparasite record for this taxa. On the other hand, Fernández (2012) recently suggested the inclusion of X. perotensis as a X. spilosoma subspecies. For X. spilosoma there are several flea records (Thrassis pansus (Jordan, 1925), T. fotus (Jordan, 1925), and E. gallinacea; Streubel, 1975; Sumrell, 1949). However, O. hirsuta is not mentioned.

Peromyscus difficilis is an endemic rodent with a wide distribution in Mexico, and fleas from at least 5 families have been collected on this species. However, Polygenis vazquezi is a new record (Fernández, García-Campusano, & Hafner, 2010). Most of the existing records were obtained from the northern part of its distribution (Acosta, 2003, 2005; Acosta et al., 2008; Ayala-Barajas et al., 1988; Barrera, 1953, 1968; Hastriter, 2004; Tipton & Méndez, 1968) and include the following families and species: Ctenophthalmidae: Anomiopsyllus sinuatus, Ctenophthalmus haagiTraub, 1950, C. micropusTraub, 1950 (T. M. Pérez-Ortíz, personal communication), C. pseudagyrtes Baker, 1904, C. tecpin Morrone et al., 2000, Epitedia wenmanni (Rothschild, 1904), Meringis arachis (Jordan, 1929), Stenoponia ponera Traub & Johnson, 1952, Strepsylla minaTraub, 1950, S. taluna Traub & Johnson, 1952, S. villai and S. davisae Traub & Johnson, 1952; Hystricopsyllidae: Atyphloceras tancitari Traub & Johnson, 1952, Hystrichopsylla llorentei Ayala & Morales, 1990, and H. occidentalis Holland, 1949; Ceratophyllidae: Jellisonia brevilobaTraub, 1950, J. grayi Hubbard, 1958, J. hayesiTraub, 1950, J. ironsi (Eads, 1947), J. wisemani Eads, 1951, Kohlsia martini Holland, 1971, K. pelaezi Barrera, 1956, Pleochaetis mundus, P. paramundusTraub, 1950, Plusaetis apollinaris (Jordan & Rothschild, 1921), P. asetus (Traub, 1950), P. aztecus (Barrera, 1954), P. dolens (Jordan & Rothschild, 1914), P. mathesoni, P. sibynus (Jordan, 1925), P. soberoni (Barrera, 1958), and 1 species of the genus Thrassis; Leptopsyllidae: Peromyscopsylla hesperomys (Baker, 1904), and Pulicidae: Echidnophaga gallinacea, and Euhoplopsyllus glacialis (Taschenberg, 1880).

For R. fulvescens, 2 fleas have been recorded: Peromyscopsylla scotti Fox, 1939 and Orchopeas leucopus (Baker, 1904) in Texas (McAllister & Wilson, 1992), and there are records of specimens of the genus Polygenis in Mexico (Petersen, 1978; Spencer & Cameron, 1982). Several fleas have been colleted for the nimble-footed mouse Peromyscus levipes Merriam, 1898 (Acosta, 2003; Whitaker & Morales-Malacara, 2005). Here we found Kholsia warthoni Traub & Johnson, 1952 representing a new record for this rodent.

The flea Dasypsyllus megasoma has only been recorded in Distrito Federal, State of México, and Oaxaca, on Merriam's Pocket gopher (Cratogeomys merriami). Hafner et al. (2005) studied the C. merriami complex and elevated the Oriental basin Pocket Gopher Cratogeomys fulvescens to specific level. Here, we reported for the first time a flea species for C. fulvescens and for the state of Veracruz, being a new host and locality record. The record of Meringis altipecten for C. fulvescens is considered as accidental because this flea has been found mainly on heteromyid rodents, as well as on the genus Polygenis (Whitaker, Wren, & Lewis, 1993). As Marshall (1981) pointed out, flea presence in not common hosts might be due to accidental transference or parasite interchange while visiting the nest or other rodent dens.

In Heteromys irroratus 3 flea species have been reported previously (Hoplopsyllus glacialis Taschenberg 1880, Polygenis gwyni (Fox, 1914), and P. martinezbaezi Vargas, 1951; Eads & Menzies, 1949; Eads, 1950; Genoways, 1973). Another 3 flea species were found for this rodent in the OB. The blackish deer mouse Peromyscus furvus was known for harboring only 1 flea species: Ctenophthalmus pseudagyrtes. Here we reported another 4 distinct flea species (Table 1). Until Jones and Genoways (1975) publication, not a single ectoparasite was known for D. phillipsii. Recently Vargas, Pérez, and Polaco (2009) reported 3 species of acari and here we reported 3 fleas parasitizing D. phillipsii.

On the other hand, the harvest mouse (R. fulvescens), and the Perote ground squirrel (X. spilosoma perotensis) were only parasitized by 1 flea species. However, these records may not be representative because only a few specimens of these rodents were collected. Collection of the Perote ground squirrel was restricted because it is an endangered taxon (Semarnat, 2010), and it is not distributed in every sampled locality.

Fleas were collected in 4 summer seasons, and flea abundance values were high, probably because rodent abundance is high in this season. Particularly, P. difficilis is very abundant, which can explain flea abundance. As mentioned by Morand and Poulin (1998), and Krasnov and Matthee (2010), population density is an important factor influencing dispersion and/or propagation, and distribution of parasites among individuals, as well as parasite specific richness. This fact might explain seasonal abundance. Collecting trips during winter would add valuable information about parasites population behavior.

The authors thank J. Falcón and J.C. Windfield for their help during fieldwork. They also thank M. Titulaer and J.J. Morrone for their critical review. Funding for this study was provided by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Técnología (Grant 200243) and Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica, UNAM, IN205408 and IN214012. They thank the Museo de Zoología for providing working space, equipment, and supplies.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.