A study was conducted to determine the biological richness of orb-weaver spiders from Calakmul municipality, Campeche, Mexico. Material deposited in the Colección Nacional de Arácnidos, Instituto de Biología, UNAM was revised. In addition, 16 collecting events were made in 14 localities of Calakmul municipality during this study. The collections were made using beating sheets and manual technique. A total of 1,151 specimens belonging to 8 families, 56 genera and 100 species were reviewed and identified. Two new species and 3 considered possibly new were found, which cannot be confirmed until specimens of both sexes are collected. According to previous studies and this work, 10 families, 65 genera and 119 species of spiders of orb-weaver spiders are present in Calakmul municipality, of which 4 families, 32 genera and 74 species are recorded for the first time. Furthermore, this work adds 3 genera and 10 species to the known diversity for the country, making a total of 14 families, 139 genera and 685 species of orb-weaver spiders recorded for Mexico.

Se realizó un estudio con el objetivo de conocer la riqueza biológica de arañas tejedoras de redes orbiculares del municipio de Calakmul, Campeche, México. Se revisó material depositado en la Colección Nacional de Arácnidos, Instituto de Biología, UNAM. Además, se realizaron 16 muestreos en 14 localidades del municipio Calakmul para la recolecta de ejemplares. Las recolectas se realizaron por medio del uso de redes de golpeo y técnica manual. Se recolectaron, revisaron e identificaron 1,151 ejemplares pertenecientes a 8 familias, 56 géneros y 100 especies. Dos especies nuevas y otras 3 se consideran posiblemente nuevas, lo que podrá confirmarse hasta obtener ejemplares de ambos sexos. De acuerdo con estudios previos y este trabajo, en el municipio Calakmul se encuentran presentes 10 familias, 65 géneros y 119 especies de arañas tejedoras, de las cuales 4 familias, 32 géneros y 74 especies se registran por primera vez. Además, este trabajo adiciona 3 géneros y 10 especies a la diversidad conocida para el país, siendo un total de 14 familias, 139 géneros y 685 especies de arañas tejedoras de redes orbiculares registradas para México.

The Calakmul municipality is the largest in the state of Campeche, in the center of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico (Conabio, 1995; Galindo-Leal, 1999; Ibarra-Manríquez, Villaseñor, Durán, & Meave, 2002). According to Galindo-Leal (1999) this region contains the greatest number of species in the Yucatán Peninsula because it is located near 5 mountain ranges, which promote this high biological richness (Villaseñor, Maeda, Colín-López, & Ortiz, 2005). The species community at Calakmul has Neotropical and Nearctic affinities, that is the reason it holds a Biosphere Reserve (Reserva de la Biosfera de Calakmul), bordering the Guatemalan department of El Petén to the south. It occupies 7,231km2 and includes about 12% of the subperennial jungles of Mexico. This reserve is one of the largest protected areas in Mexico, covering more than 14% of the state and it is considered one of the most diverse of Mexico since it conserves many species, some of them threatened (Arreola, Villalobos, Hernández, Sánchez, & Caamal, 2008; Conabio, 1995; Folan and García, 2001).

In Mexico there are reported 2,385 species of spiders, 453 genera, and 69 families (Francke, 2013; World Spider Catalog, 2016), representing 5.1% of the total world diversity (113 families, 4,025 genera, and 46,351 species), and one of the most studied spider groups has been the orb-weaver spiders. Orb-weavers are among the most diverse lineages of araneomorph spiders and are represented by 2 superfamilies: Araneoidea, with 19 families, 1,132 genera, and 12,370 species, and Deinopoidea, with 2 families, 20 genera and 341 species (Hormiga and Griswold, 2014; World Spider Catalog, 2016). According to Jiménez (1996), García-Villafuerte (2009), Ibarra-Núñez, Maya-Morales, and Chamé-Vázquez (2011), and World Spider Catalog (2016), in Mexico there are currently distributed 13 families, 144 genera and 688 species of orb-weaver spiders. In the state of Campeche there are reported 32 genera and 41 species of spiders representing almost one-third of the endemic species of Mexico (Jiménez, 1996); however, there are no studies on diversity of orb-weavers and the few previous records were made by sporadic collections. Hoffmann (1976), Gertsch (1977) and Reddell (1977) reported 6 families, 13 genera and 17 species for Campeche. After that, Exline and Levi (1962), Levi (1957, 1968, 1975, 1976, 1991, 1992, 1995a,b, 1997, 1999, 2005), and Piel (2001) found new records for 23 species of 13 genera of family Araneidae, and 3 species of 3 genera of Theridiidae. Consistent with this information, until 2005, there were reported 6 families, 31 genera and 44 species of orb-weaver spiders from Campeche, being Araneidae and Theridiidae the families with the highest diversity with 16 genera and 27 species, and 11 genera and 13 species respectively. The present study is an update of the diversity of orb-weaver spiders for the last 10 years for Calakmul and Campeche, as well for the Yucatán Peninsula and Mexico.

Materials and methodsWe studied unidentified preserved spiders in 80% ethanol from the arachnological collection (CNAN) of Instituto de Biología, UNAM. These specimens were collected in November 1991, June 1997, April and July 1998, July 2001, July 2007, and July 2010 at Calakmul, Campeche. Also we made a survey in October 2011 to collect specimens of orb-weaver spiders.

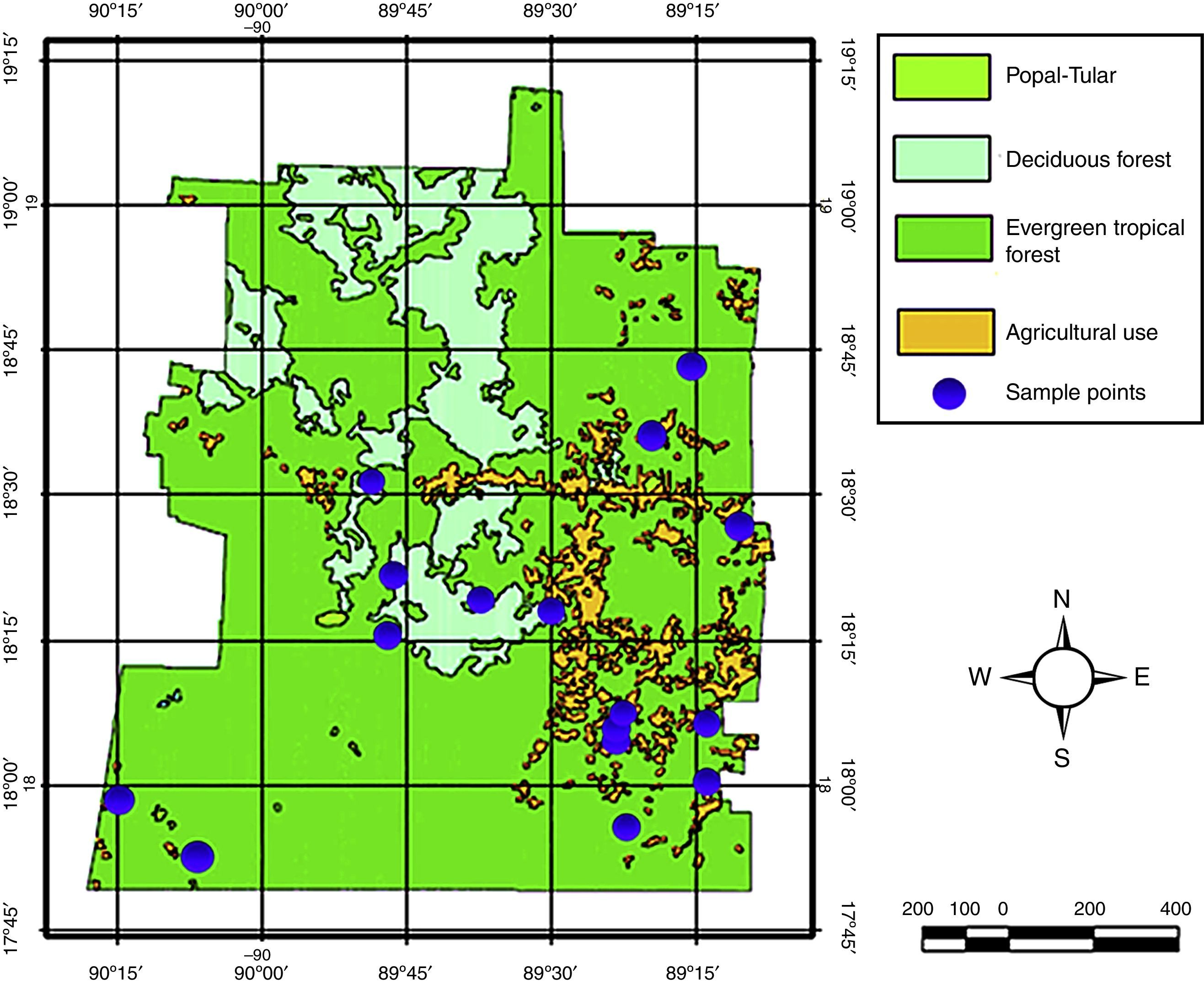

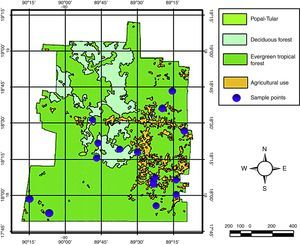

The sampling was conducted in the rainy season because this is when an increase in the abundance and richness of spiders has been reported in other studies in Mexico (Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Solís-Catalán, & Valdez-Mondragón, 2015; Valdez-Mondragón, 2006). Also, the reproduction of most of the species occurs in this season, being a period where the presence of food is constant (Nogueira, Pinto da Rocha, & Brescovit, 2006). We visited the borders of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve on the center and south of the municipality (Fig. 1), from October 10 to 17 in 2011 to collect orb-weaver spiders. We visited 14 localities and made 16 samplings (Fig. 1), 14 were diurnal and 2 nocturnal. The criteria for selection of localities were the presence of a high conservation level and low or absent flooding to ease access to the vegetation. The predominant vegetation in the localities was tropical rainforest, vegetation type present in 12 of 14 localities, the other 2 localities presented deciduous forest vegetation and a cave environment. Five localities were well preserved and 9 showed some degree of disturbance, mainly in the southwest portion of the municipality, where there were plots and pastures, instead of forest (Fig. 2). During mornings, we used beating sheets of 70cm×70cm size to collect spiders. We placed them under the trees and shrubs in 1m2 quadrats, and then beat the vegetation with a 40cm long stick. The spiders were collected with arachnological aspirators into plastic vials. At most localities we made about 20 beatings; however, in localities with disturbed vegetation we made only 10. Additionally, we searched under rocks and fallen logs exhaustively for spiders and collected them by hand or using forceps, arachnological aspirators and/or small brushes. At night we searched for orb-weaver spiders on the vegetation using headlamps with white light and collected them with an aspirator or directly into vials. A team of 5 people worked 1h during the day and 2h at night at each locality. Considering that only in 2 localities we made nocturnal collections, the sampling effort was 18h/person, totaling 90h among the 5 participants. All specimens were preserved in glass jars with ethanol (80%), labeled with their respective collection data, and deposited in the CNAN.

The revision of specimens was made in a stereoscopic microscope Nikon SMZ 745T, where sexual and somatic characters were revised for each specimen. The dissection of male pedipalps and epigyna was made following Levi's protocol (1965), and for identifications to species level we used specialized literature and taxonomic keys.

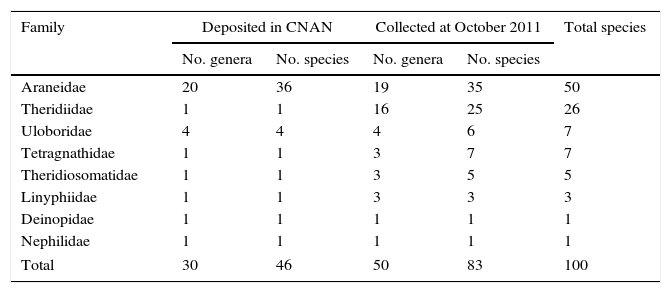

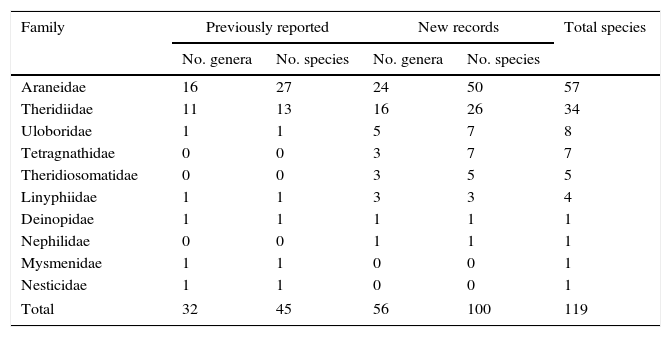

ResultsConsidering the material previously collected plus the newly collected material in October, we identified 1,151 specimens, belonging to 8 families, 56 genera and 100 species of orb-weaver spiders (Table 1). Regarding the material deposited in the CNAN, we sorted and identified 8 families, 30 genera, and 46 species of orb-weavers (Table 1). The families with the highest number of species were Araneidae with 36 species (78%), and Uloboridae, with 4 species (8.7%). It is important to emphasize that these spiders were captured using mainly manual techniques, and the collections were focused on collecting all arachnid orders. Then, in the sampling made in October 2011 we found a total of 8 families, 50 genera, and 83 species (Table 1). The families with the highest diversity in these samplings were Araneidae and Theridiidae with 35 (42.2%) and 25 (30.1%) species, respectively (Table 1). Considering the published records until 2005 and the new results from this study, in the Calakmul municipality and the state of Campeche, currently 10 families, 65 genera and 119 species of spiders of orb-weaver spiders are reported (Table 2; Appendix 1). The most diverse families were Araneidae with 57 (47.9%) and Theridiidae with 35 species (28.6%) (Table 2).

Number of genera and species per family of orb-weaver spiders previously deposited in CNAN plus those collected in October 2011.

| Family | Deposited in CNAN | Collected at October 2011 | Total species | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. genera | No. species | No. genera | No. species | ||

| Araneidae | 20 | 36 | 19 | 35 | 50 |

| Theridiidae | 1 | 1 | 16 | 25 | 26 |

| Uloboridae | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 7 |

| Tetragnathidae | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 7 |

| Theridiosomatidae | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Linyphiidae | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Deinopidae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nephilidae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 30 | 46 | 50 | 83 | 100 |

Updated diversity of orb-weaver spiders considering the published records until 2005 and the results from this study.

| Family | Previously reported | New records | Total species | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. genera | No. species | No. genera | No. species | ||

| Araneidae | 16 | 27 | 24 | 50 | 57 |

| Theridiidae | 11 | 13 | 16 | 26 | 34 |

| Uloboridae | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 8 |

| Tetragnathidae | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 7 |

| Theridiosomatidae | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Linyphiidae | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Deinopidae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nephilidae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mysmenidae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Nesticidae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 32 | 45 | 56 | 100 | 119 |

Two new species were found: Dipoena sp. nov. (Theridiidae) and Hingstepeira sp. nov. (Araneidae), and 4 are considered possibly new: Pozonia sp. (Araneidae), Ceratinopsis sp. (Linyphiidae), Conifaber sp. (Uloboridae), and Ogulnius sp. (Theridiosomatidae). However, in these cases it is necessary to collect adult specimens of both sexes to confirm the identifications, because there are genera with a great number of species that are described from only 1 sex, and proper comparisons with the specimens collected cannot be completed.

DiscussionRegarding the genera of orb-weavers found in this study, the most diverse genera of Araneidae were Mangora Cambridge, 1889 and Micrathena Sundevall, 1833 with 6 species each, whereas 16 genera (61.1%) were represented by a single species (Appendix 1). Among Theridiidae, the most diverse genera were Faiditus Keyserling, 1884 and Theridion Walckenaer, 1805 with 4 species each, whereas 11 genera (42.3%) were represented by 1 species (Appendix 1). The high diversity of Araneidae and Theridiidae has been also reported by Silva and Coddington (1996). According to Deza and Andía (2009), the diversity of Araneidae should increase with manual exhaustive sampling, in both diurnal and nocturnal searches, because it considers every habitat in the field. In this study, one of the collection techniques was manual, but we could only carry out 2 nocturnal collections because of the rain. Therefore, it is possible that the diversity of Araneidae in Calakmul could be higher if more nocturnal collections are made. For Uloboridae, the most diverse genus was Uloborus Latreille, 1806, represented by 3 species, whereas 37.5% of the genera were represented by a single species (Appendix 1). Our results are similar to that found by Silva and Coddington, 1996, in which Uloboridae represented 8.9% of the diversity of orb-weavers collected during rainy season in October in Pakitza, Peru. In the case of Tetragnathidae family, the genus Tetragnatha Latreille, 1804 was the most diverse with 4 species; and Opas Cambridge, 1896 was the only genus represented by a single species (Appendix 1). The diversity of Tetragnathidae was quite similar to that found by Rico, Beltrán, Álvarez, and Flórez (2005) in Gorgona Island, Colombia in which the family represented 8.3% of the diversity of orb-weaver spiders. That study was comparable to ours because they made only one collection event and the altitude, vegetation, and season conditions were similar. For Theridiosomatidae, the most diverse genera were Epeirotypus Cambridge, 1894 and Theridiosoma Cambridge, 1879 with 2 species each one, whereas the genus Ogulnius Cambridge, 1882 was represented by 1 species, which is possibly new (Appendix 1) and the family represents 6% of the total diversity found. According to Silva and Coddington, 1996, the diversity of this family increases at the beginning of the dry season; and the spiders of genus Epeirotypus were collected in spiny trunks of palms, and spiders of genus Theridiosoma were found in webs built over topsoil. Thus, it is important to search for these spiders in different microhabitats, in different types of vegetation, and in different seasons to get a greater species richness.

All the genera found of the families Linyphiidae, Deinopidae, Mysmenidae, Nephilidae, and Nesticidae were represented by 1 species each. According to these results, 65.2% of the genera reported for Calakmul and Campeche are represented by only 1 species (Appendix 1). The low diversity found in some families of orb-weaver spiders has been also reported in other studies. In the study conducted by Rico et al. (2005), the diversity of Uloboridae was greater and represented 13.8% of orb-weavers. In contrast, Ferreira-Ojeda, Flórez, and Sabogal-González (2009) found that family Uloboridae was only represented by 1 species (2.8%) in Sierra Nevada, Santa Marta, Colombia. The difference in results could be influenced by weather, vegetation, and altitude of the localities sampled. The family Linyphiidae presented low diversity, with only 3 genera and 3 species (3.6%). This low diversity is similar to that found by Silva and Coddington (1996), where Linyphiidae represented 1.7% of orb-weaver diversity. That study, as this one, was conducted in tropical rainforest at a low elevation (356m). According to Russell-Smith and Stork (1994), Sørensen (2004) and Ibarra-Núñez et al. (2011) this family is not diverse in low tropical regions and the species richness increases with elevation. In the Yucatán Peninsula, the elevation in the southern region is slightly above 200m, therefore this region is quite low. In contrast, in a revision by Ibarra-Núñez et al. (2011), who studied the diversity of spiders in the Biosphere Reserve of Tacaná Volcano, Chiapas, at an altitude above 2,000m, found that Linyphiidae were represented by 20 species, almost 25% of the diversity of orb-weaver spiders.

The less diverse families in Calakmul were Nephilidae and Deinopidae. The family Nephilidae is not diverse in America, and is represented by only 2 genera and 6 species (World Spider Catalog, 2016). Currently, the genus Nephila has colonized at least 40 islands and landmasses, and many species have an extended distribution (Kuntner and Agnarsson, 2011). In the case of Nephila clavipes (Linnaeus, 1767), it is distributed from the USA to Argentina. The low diversity of the genus could be due to its high dispersion capacity, which limits its diversification and maintains gene flow among geographically distant populations (Kuntner and Agnarsson, 2011). The diversity of Deinopidae is quite similar to Nephilidae; this family is represented by 1 genus and 19 species in America, of which 1 genus and 2 species (Deinopis aurita Cambridge, 1902 and Deinopis longipes Cambridge, 1902) have been reported for Mexico, being D. longipes the species found in this study. In other studies of diversity of orb-weaver spiders, specimens of this family have not been reported (Ferreira-Ojeda et al., 2009; Rico et al., 2005; Romo and Flórez, 2008) or when they are found, are represented by only 1 species (Blanco-Vargas, Amat-García, & Flórez-Daza, 2003; Silva and Coddington, 1996). According to Coddington, Kuntner, and Opell (2012), despite the tropical distribution of the family, their size, and their habits, specimens of this family are poorly represented both in field and in biological collections, therefore they are considered rare.

Of the 8 families, 57 genera, and 100 species of orb-weavers found in this study, only 4 families, 24 genera and 27 species (27%) were previously reported in others works for Calakmul and Campeche. In contrast, 10 genera and 27 species of Araneidae, 9 genera and 20 species of Theridiidae and 15 genera and 27 species of Deinopidae, Linyphiidae, Nephilidae, Tetragnathidae, Theridiosomatidae, and Uloboridae represent new distribution records for Calakmul and Campeche. Regarding the new records for Mexico, 3 genera and 5 species have not previously reported for the country. For Araneidae, the species Ocrepeira serrallesi (Bryant, 1947) was previously reported only from the West Indies (Levi, 1993); and this is the first time that the genus Higstepeira Levi, 1995 is reported for North America (Levi, 1995b). For Theridiidae, Faiditus chickeringi (Exline and Levi, 1962) and Theridion chiriquiLevi, 1959 were previously only reported for Panama (Exline and Levi, 1962; Levi, 1959). In the case of Theridiosomatidae, the genus Ogulnius is reported for North America for the first time (Coddington, 1986). Also, Epeirotypus chavarriaCoddington, 1986 was only previously reported for Costa Rica (Coddignton, 1986), and Theridiosoma zygops (Chamberlin and Ivie, 1936) was reported for Panama (Chamberlin and Ivie, 1936). For Uloboridae, is the first time that the genus Conifaber Opell, 1982 is reported for North America (Grismado, 2004; Lubin, Opell, Eberhard, & Levi, 1982).

Most of the new records for Mexico are for species that were previously registered in localities that are very distant from Calakmul and Campeche, such as Hingstepeira, Conifaber, and Ogulnius. The orb-weaver spiders have a dispersion method called “ballooning” and it consists in the production of silk threads caused by friction of air with the spinnerets. The silk threads act like a parachute, allowing spiders travel long distances (Sutter, 1992). Considering this, it is possible that many species previously registered only for Central and South America, are also distributed in North America, and therefore in Mexico. Regarding the 2 new species Dipoena sp. nov. (Theridiidae) and Hingstepeira sp. nov. (Araneidae), and the possibly new: Pozonia sp. (Araneidae), Ceratinopsis sp. (Linyphiidae), Conifaber sp. (Uloboridae), and Ogulnius sp. (Theridiosomatidae), it is necessary to collect adult specimens of both sexes to confirm the identifications, because there are genera with a great number of species that are described from only 1 sex, and proper comparisons with the specimens collected cannot be carried out.

With the diversity of orb-weavers registered until 2011, in Calakmul and Campeche currently there are found 10 families, 65 genera, and 119 species. However, this diversity could increase if more systematized sampling events and collecting techniques are implemented, and even studying the fluctuation of species numbers could be determined according to the different seasons. Some species that were previously reported for Campeche were not found in this study; the absence of these species in our collections could be influenced by differences in collection techniques and seasonality, but also by degree of perturbation of the native vegetation. In addition, some species such as Hingstepeira sp. nov. are reported from localities inside of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve and were not found in the present study. Thus, it is possible that this species is endemic to the Reserve, or that it is easily found there because of the high level of conservation, as opposed to some of our other sampling localities (Fig. 2); and the same could be happening with other species. The family Araneidae resulted the most diverse, with 47.9% of the species of orb-weaver spiders, but despite the great number of studies on the taxonomy and species richness of Araneidae, it is considered that almost the 50% of the diversity of the family is still unknown (Coddington and Levi, 1991). Therefore, it is necessary to intensify the number of studies on orb-weaver spiders, mainly in the Neotropical region in order to increase their known diversity, because in these regions is where the greatest level of species richness of this family has been found (Flórez, 1998). According to the diversity of the orb-weavers for Mexico, the families Theridiosomatidae, Mysmenidae, Anapidae, and Symphytognathidae are the less diverse (except Nephilidae and Deinopidae); it is possible that their low diversity is because these spiders are tiny and they are difficult to collect using manual techniques. Therefore, it is recommended that in future collections special techniques should be used to capture these types of spiders, such as collection of leaf litter and the use of Berlese funnels to have a more accurate approach to document the real diversity of these families.

We thank Oscar F. Francke for his comments, fieldwork, support and corrections on the manuscript, Juan J. Morrone for his recommendations to improve the manuscript, Griselda Montiel Parra and Diego Barrales Alcalá for their help with the fieldwork, to Guillermo Ibarra for his help with the identification of the spiders, and the reviewers for their comments and improvement of the manuscript. To the Instituto de Biología (IBUNAM) and Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas of UNAM. The second author thanks to the program “Cátedras Conacyt”, Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Conacyt) for the scientific support for project No. 59: “Laboratorio Regional de Biodiversidad y Cultivo de Tejidos Vegetales (LBCTV) del Instituto de Biología (IBUNAM), sede Tlaxcala”. To the people from different localities in Campeche for the help and facilities in the fieldwork. The specimens were collected under Scientific Collector Permit FAUT-0175 from the Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat) to Oscar F. Francke.

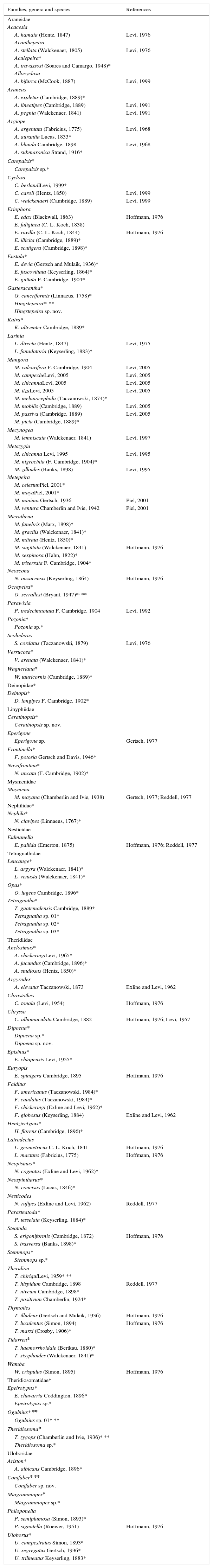

| Families, genera and species | References |

|---|---|

| Araneidae | |

| Acacesia | |

| A. hamata (Hentz, 1847) | Levi, 1976 |

| Acanthepeira | |

| A. stellata (Walckenaer, 1805) | Levi, 1976 |

| Aculepeira* | |

| A. travassosi (Soares and Camargo, 1948)* | |

| Allocyclosa | |

| A. bifurca (McCook, 1887) | Levi, 1999 |

| Araneus | |

| A. expletus (Cambridge, 1889)* | |

| A. lineatipes (Cambridge, 1889) | Levi, 1991 |

| A. pegnia (Walckenaer, 1841) | Levi, 1991 |

| Argiope | |

| A. argentata (Fabricius, 1775) | Levi, 1968 |

| A. aurantia Lucas, 1833* | |

| A. blanda Cambridge, 1898 | Levi, 1968 |

| A. submaronica Strand, 1916* | |

| Carepalxis* | |

| Carepalxis sp.* | |

| Cyclosa | |

| C. berlandiLevi, 1999* | |

| C. caroli (Hentz, 1850) | Levi, 1999 |

| C. walckenaeri (Cambridge, 1889) | Levi, 1999 |

| Eriophora | |

| E. edax (Blackwall, 1863) | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| E. fuliginea (C. L. Koch, 1838) | |

| E. ravilla (C. L. Koch, 1844) | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| E. illicita (Cambridge, 1889)* | |

| E. scutigera (Cambridge, 1898)* | |

| Eustala* | |

| E. devia (Gertsch and Mulaik, 1936)* | |

| E. fuscovittata (Keyserling, 1864)* | |

| E. guttata F. Cambridge, 1904* | |

| Gasteracantha* | |

| G. cancriformis (Linnaeus, 1758)* | |

| Hingstepeira*, ** | |

| Hingstepeira sp. nov. | |

| Kaira* | |

| K. altiventer Cambridge, 1889* | |

| Larinia | |

| L. directa (Hentz, 1847) | Levi, 1975 |

| L. famulatoria (Keyserling, 1883)* | |

| Mangora | |

| M. calcarifera F. Cambridge, 1904 | Levi, 2005 |

| M. campecheLevi, 2005 | Levi, 2005 |

| M. chicannaLevi, 2005 | Levi, 2005 |

| M. itzaLevi, 2005 | Levi, 2005 |

| M. melanocephala (Taczanowski, 1874)* | |

| M. mobilis (Cambridge, 1889) | Levi, 2005 |

| M. passiva (Cambridge, 1889) | Levi, 2005 |

| M. picta (Cambridge, 1889)* | |

| Mecynogea | |

| M. lemniscata (Walckenaer, 1841) | Levi, 1997 |

| Metazygia | |

| M. chicanna Levi, 1995 | Levi, 1995 |

| M. nigrocinta (F. Cambridge, 1904)* | |

| M. zilloides (Banks, 1898) | Levi, 1995 |

| Metepeira | |

| M. celestunPiel, 2001* | |

| M. mayaPiel, 2001* | |

| M. minima Gertsch, 1936 | Piel, 2001 |

| M. ventura Chamberlin and Ivie, 1942 | Piel, 2001 |

| Micrathena | |

| M. funebris (Marx, 1898)* | |

| M. gracilis (Walckenaer, 1841)* | |

| M. mitrata (Hentz, 1850)* | |

| M. sagittata (Walckenaer, 1841) | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| M. sexpinosa (Hahn, 1822)* | |

| M. triserrata F. Cambridge, 1904* | |

| Neoscona | |

| N. oaxacensis (Keyserling, 1864) | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| Ocrepeira* | |

| O. serrallesi (Bryant, 1947)*, ** | |

| Parawixia | |

| P. tredecimnotata F. Cambridge, 1904 | Levi, 1992 |

| Pozonia* | |

| Pozonia sp.* | |

| Scoloderus | |

| S. cordatus (Taczanowski, 1879) | Levi, 1976 |

| Verrucosa* | |

| V. arenata (Walckenaer, 1841)* | |

| Wagneriana* | |

| W. tauricornis (Cambridge, 1889)* | |

| Deinopidae* | |

| Deinopis* | |

| D. longipes F. Cambridge, 1902* | |

| Linyphiidae | |

| Ceratinopsis* | |

| Ceratinopsis sp. nov. | |

| Eperigone | |

| Eperigone sp. | Gertsch, 1977 |

| Frontinella* | |

| F. potosia Gertsch and Davis, 1946* | |

| Novafrontina* | |

| N. uncata (F. Cambridge, 1902)* | |

| Mysmenidae | |

| Maymena | |

| M. mayana (Chamberlin and Ivie, 1938) | Gertsch, 1977; Reddell, 1977 |

| Nephilidae* | |

| Nephila* | |

| N. clavipes (Linnaeus, 1767)* | |

| Nesticidae | |

| Eidmanella | |

| E. pallida (Emerton, 1875) | Hoffmann, 1976; Reddell, 1977 |

| Tetragnathidae | |

| Leucauge* | |

| L. argyra (Walckenaer, 1841)* | |

| L. venusta (Walckenaer, 1841)* | |

| Opas* | |

| O. lugens Cambridge, 1896* | |

| Tetragnatha* | |

| T. guatemalensis Cambridge, 1889* | |

| Tetragnatha sp. 01* | |

| Tetragnatha sp. 02* | |

| Tetragnatha sp. 03* | |

| Theridiidae | |

| Anelosimus* | |

| A. chickeringiLevi, 1965* | |

| A. jucundus (Cambridge, 1896)* | |

| A. studiosus (Hentz, 1850)* | |

| Argyrodes | |

| A. elevatus Taczanowski, 1873 | Exline and Levi, 1962 |

| Chrosiothes | |

| C. tonala (Levi, 1954) | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| Chrysso | |

| C. albomaculata Cambridge, 1882 | Hoffmann, 1976; Levi, 1957 |

| Dipoena* | |

| Dipoena sp.* | |

| Dipoena sp. nov. | |

| Episinus* | |

| E. chiapensis Levi, 1955* | |

| Euryopis | |

| E. spinigera Cambridge, 1895 | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| Faiditus | |

| F. americanus (Taczanowski, 1984)* | |

| F. caudatus (Taczanowski, 1984)* | |

| F. chickeringi (Exline and Levi, 1962)* | |

| F. globosus (Keyserling, 1884) | Exline and Levi, 1962 |

| Hentziectypus* | |

| H. florens (Cambridge, 1896)* | |

| Latrodectus | |

| L. geometricus C. L. Koch, 1841 | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| L. mactans (Fabricius, 1775) | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| Neopisinus* | |

| N. cognatus (Exline and Levi, 1962)* | |

| Neospintharus* | |

| N. concisus (Lucas, 1846)* | |

| Nesticodes | |

| N. rufipes (Exline and Levi, 1962) | Reddell, 1977 |

| Parasteatoda* | |

| P. tesselata (Keyserling, 1884)* | |

| Steatoda | |

| S. erigoniformis (Cambridge, 1872) | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| S. trasversa (Banks, 1898)* | |

| Stemmops* | |

| Stemmops sp.* | |

| Theridion | |

| T. chiriquiLevi, 1959* ** | |

| T. hispidum Cambridge, 1898 | Reddell, 1977 |

| T. niveum Cambridge, 1898* | |

| T. positivum Chamberlin, 1924* | |

| Thymoites | |

| T. illudens (Gertsch and Mulaik, 1936) | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| T. luculentus (Simon, 1894) | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| T. marxi (Crosby, 1906)* | |

| Tidarren* | |

| T. haemorrhoidale (Bertkau, 1880)* | |

| T. sisyphoides (Walckenaer, 1841)* | |

| Wamba | |

| W. crispulus (Simon, 1895) | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| Theridiosomatidae* | |

| Epeirotypus* | |

| E. chavarria Coddington, 1896* | |

| Epeirotypus sp.* | |

| Ogulnius* ** | |

| Ogulnius sp. 01* ** | |

| Theridiosoma* | |

| T. zygops (Chamberlin and Ivie, 1936)* ** | |

| Theridiosoma sp.* | |

| Uloboridae | |

| Ariston* | |

| A. albicans Cambridge, 1896* | |

| Conifaber* ** | |

| Conifaber sp. nov. | |

| Miagrammopes* | |

| Miagrammopes sp.* | |

| Philoponella | |

| P. semiplumosa (Simon, 1893)* | |

| P. signatella (Roewer, 1951) | Hoffmann, 1976 |

| Uloborus* | |

| U. campestratus Simon, 1893* | |

| U. segregatus Gertsch, 1936* | |

| U. trilineatus Keyserling, 1883* | |

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.