To describe a case of rhabdomyosarcoma in an elderly patient.

MethodsAn exenteration surgery was performed of the right orbit with desperiostization and temporal muscle-skin flap rotation to cover the defect in a 96 year old patient with a history of right eye exotropia.

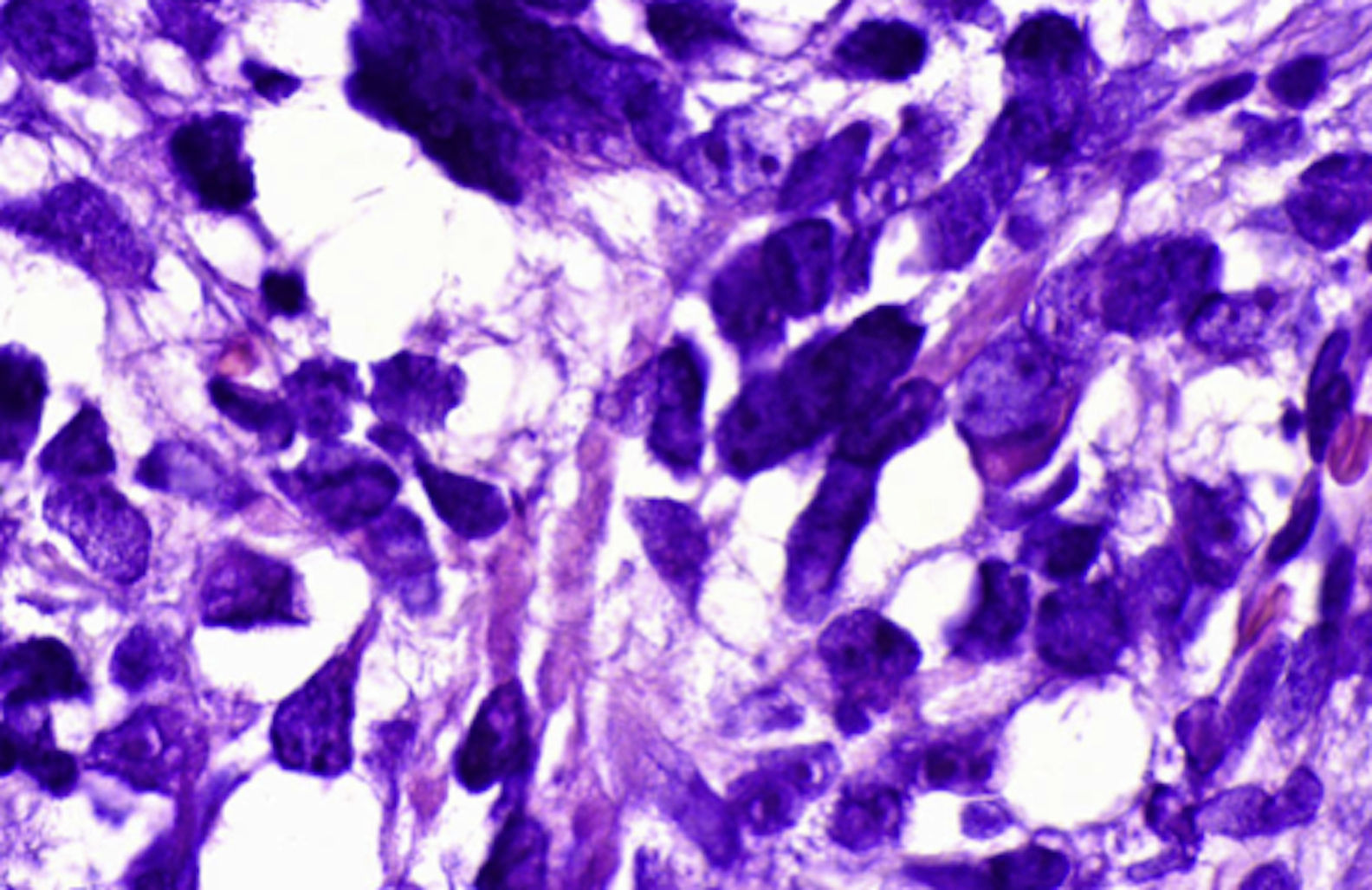

ResultsThe pathology report showed a malignant striate muscle neoplasm with pleomorphic neuclei of variable size with discromic and disperse cromatine that was consistent with pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma.

ConclusionsRhabdomyosarcoma, although a malignancy mainly seen in children can also affect other age groups, even the elderly.

Describir un caso de rabdomiosarcoma en un paciente anciano.

MétodosUna cirugía de exenteración se realizó de la órbita derecha con desperiostization y rotación colgajo de músculo-piel temporal para cubrir el defecto en un paciente de 96 años con antecedentes de exotropía ojo derecho.

ResultadosEl estudio anatomopatológico mostró una neoplasia de músculo estriado maligno con núcleos pleomórficos de tamaño variable, con cromatina dispersa y discrómica que era consistente con rabdomiosarcoma pleomórfico.

ConclusionesEl rabdomiosarcoma, aunque un tumor maligno visto principalmente en niños puede afectar también a otros grupos de edad, incluso a el de los ancianos.

Rhabdomyosarcoma is a neoplasm that affects mainly children in most case series, although infrequently can affect people of different ages. In the elderly it has been reported only in a few cases.1 The purpose of this case report is to describe a case of a pleoporphic rhabdomyosarcoma in an elderly patient.

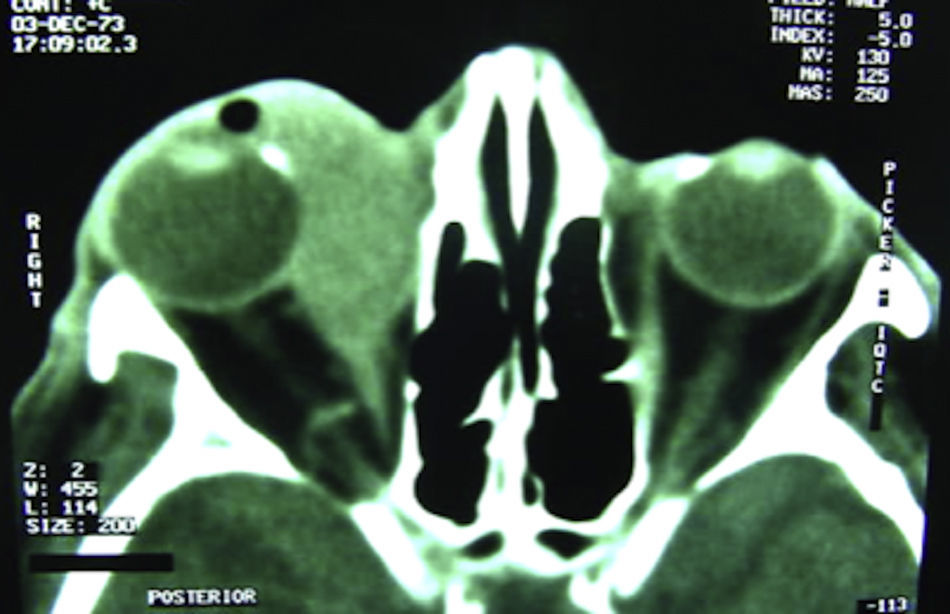

Case presentationA 96 year-old male patient presented with a history pain, exotropia and proptosis of his right eye of about one year. He had a history of neovascular glaucoma secondary to central retinal vein occlusion of the same eye. His right eye's visual acuity was no light perception, 40mmHg of intraocular pressure, posterior synechiae, and a total cataract (Fig. 1). On CT scan there was there was a tumoral lesion in the right orbit that extended from the upper eyelid, surrounding the globe and displacing it as well as the muscle cone at the vertex with loss of the internal rectus muscle contours. The lesion was isointense to the extraocular muscles (Fig. 2).

It measured 38.18mm×33.0mm. Considering the presence of a painful eye and the extent of the orbital involvement, an exenteration surgery was performed of the right orbit with desperiostization and temporal muscle-skin flap rotation to cover the defect.

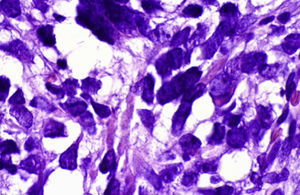

The pathology report showed a malignant striate muscle neoplasm with pleomorphic neuclei of variable size with discromic and disperse cromatine. The contours of the cells were irregular with eosinophilic citoplasm. Numerous atypic mitosis were observed in all cells. The neoplasm infiltrates adipose and muscle tissue surrounding it (Fig. 3). The histopathology diagnosis was rhabdomyosarcoma infiltrating adipous and muscle tissue as well as part of the sclera.

DiscussionRhabdomyosarcoma is the most common childhood primary soft-tissue sarcoma of the orbit1 and indeed is the most common childhood soft-tissue malignancy elsewhere in the body. Orbital lesions represent ∼10% of all rhabdomyosarcomas.2 Originally thought to arise from striated muscle cells, immunohistochemistry has now demonstrated that the tumor arises from malignant transformation of pluripotential mesenchymal cells.

There is a bimodal age distribution of orbital rhabdomyosarcoma, with ∼75% occurring within the first decade of life. This observation is the reason of seeing this pathology in adults and even in the elderly like our patient although this is somewhat rare.

There is a slight predominance of males.

The classic picture in the orbit is one of rapidly progressive unilateral proptosis that develops over days to weeks. In some instances, the growth may be so rapid that the proptosis becomes massively exacerbated over a weekend. This observation could not be corroborated in our patient due to he attended our clinic a year after he noticed the proptosis.

The most frequent location for the tumor is in the superonasal quadrant, but it may be seen anywhere in the orbit, including the retrobulbar space. The alveolar variant is held to be more common in the inferior orbit. This observation also coincides with the presentation in our patient.

Proptosis and paraxial globe displacement are the most common findings on clinical examination.3 Eyelid edema is also common, with an increased vascularity due to subadjacent blood vessels supplying the tumor; however, the massive chemotic edema and erysipeloid skin changes accompanying orbital cellulitis are generally missing.

Despite the often rapid clinical presentation, imaging studies often reveal bland, well-circumscribed lesions, which belie the true malignant nature of the process. On CT the tumor is isointense to muscle, and typically demonstrates homogeneous enhancement of the soft tissue mass. Although rarely the paranasal sinuses may become secondarily involved through bone erosion, they are more often clear of disease, which may help to differentiate rhabdomyosarcoma from orbital cellulitis in nontraumatic cases. In this regard, CT scan in our patient shows all these characteristics mainly the sparing of the paranasal sinuses.

Any patient with suspected rhabdomyosarcoma should undergo urgent orbital biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of a fulminant and rapidly developing proptosis in a child should include orbital cellulitis secondary to paranasal sinus infection (the most common cause of unilateral proptosis in children), idiopathic inflammatory orbital pseudotumor, conjunctivitis or allergic edema, chocolate cyst formation within a lymphangioma, and in the elderly of course metastatic tumor. This was ruled out in our patient and he had no history of primary malignant neoplasias elsewhere,

In 1997, the IRS Group published a comprehensive report on the subset of patients with orbital rhabdomyosarcoma, representing patients treated under protocols from trials I through IV.2 Eighty percent of orbital tumors were embryonal in subtype, botryoid in 4%, alveolar in 9%, and anaplastic in 0%. Tumors were catagorized as group I in 3% of patients, group II in 20%, group III in 74%, and group IV in 3%. Other large studies have echoed these figures.3 Therefore, tumors are confined to the orbit (groups I and II) at initial presentation, but they are usually incompletely resected (group III) in the majority of cases, therefore necessitating postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

The range of therapeutic options for orbital disease has been revolutionized over the past decades. Up to the 1970s, the standard of care for rhabdomyosarcoma was to attempt complete resection of the tumor, which meant disfiguring enucleation and possible exenteration.

After exenteration, survival rates were only 35%.1 Beginning in the mid 1960s local radiotherapy was introduced, followed by chemotherapy, which was generally reserved for patients with recurrent or disseminated disease.

Beginning with the IRSs in the 1970s, protocols combining radiotherapy and specific chemotherapeutic regimens were introduced, based on tumor grade and stage. These treatment protocols are extremely dynamic, evolving over the course of the various trials. With incomplete excision of the orbital tumor coupled with postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy the survival rate of patients with orbital rhabdomyosarcoma is 93%.4

An alveolar subtype within the orbit portends a worse prognosis, although this was not the case of por patient that showed a pleomorphic variant of the disease. This histopathological form carries a better prognosis.

Current rates of enucleation and/or exenteration in primary orbital rhabdomyosarcoma ranges from 7%3 to 14%.5

The decision of exenteration was made upon the fact that he had a blind, painful eye and maybe because of his age he could not withstand radiotherapy.

ConclusionsAlthough rare, rhabdomyosarcoma should be considered in patients of all ages including the elderly.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingNo endorsement of any kind received to conduct this study/article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors wish to thank all the staff of Instituto Oftalmológico Privado of Irapuato, Mexico.