Class III malocclusion is considered the most severe within the classification of malocclusions. In most patients, the etiology may be divided in skeletal and dentoalveolar components. In the adult patient, because skeletal growth has ceased, treatment options are reduced to two possibilities: camouflage or orthognathic surgery. These complex cases require careful planning, a multidisciplinary approach and patient cooperation.

Material and methodsA 44-year-old female with skeletal class III malocclusion, brachyfacial biotype, concave profile, bilateral molar class III, non-assessable canine class due to the presence of temporary canines; an edge-to-edge incisor relationship and anterior crossbite of the temporary canines.

ObjectiveTo improve the maxillo-mandibular relationship obtaining good occlusal function as well as to improve the aesthetics of the patient through a multidisciplinary treatment.

ResultsMaxillo-mandibular relationship was improved, canine guidance was achieved with implants and prosthesis, a bilateral class I molar relationship was obtained as well as good occlusal function. Periodontal health was maintained.

ConclusionThe multidisciplinary approach was successful in achieving the desired therapeutic results of improved function, improved aesthetics and improved self-esteem in this patient.

La maloclusión clase III es considerada como la más severa dentro de su clasificación. En la mayoría de los pacientes, la etiología de la misma puede estar combinada entre componentes esqueléticos y dentoalveolares. En el paciente adulto, debido a que el crecimiento esquelético ha cesado, las opciones de tratamiento se reducen a dos posibilidades: camuflaje o cirugía ortognática. Estos casos complejos requieren un planeamiento cuidadoso, una actuación multidisciplinaria y cooperación por parte del paciente.

Material y métodosSe reporta caso de una paciente de género femenino de 44 años de edad con maloclusión clase III esquelética, biotipo braquifacial, perfil cóncavo, clase III molar bilateral, clase canina no valorable por presencia de caninos temporales, mordida borde a borde anterior y cruzada a nivel de caninos temporales.

ObjetivoMejorar la relación maxilomandibular, obteniendo adecuada función oclusal; así como mejorar la estética de la paciente mediante el tratamiento multidisciplinario.

ResultadosSe mejoró la relación maxilomandibular, se consiguió dar guía canina, mediante las prótesis con implantes, clase I molar bilateral, salud periodontal y función oclusal adecuada.

ConclusiónEl caso de la paciente que se reporta en el presente artículo cumple con este enfoque interdisciplinario, obteniendo resultados que resuelven la problemática inicial y, de esta manera, logrando mejoría en la estética y función dentofaciales.

Adulthood is a stage of functional balance where growth has been completed and the individual reaches its greatest physical and intellectual development.1 Adult patients with dento-skeletal deformities usually require treatments where most cases need interdisciplinary intervention, an example of this being the surgical-orthodontic treatment; however, these complex cases require a precise diagnosis, a careful treatment plan, and patient cooperation. A poor aesthetically pleasing facial appearance is usually the main cause of consultation but it is often accompanied with functional problems, temporomandibular joint disorders and psychosocial aspects.2 Approximately 4% of the population has a dentofacial deformity that requires surgical-orthodontic treatment to correct it; the most common indications for surgical treatment are severe skeletal class II and class III patients and vertical skeletal discrepancies, in patients who have finished growth. Proffit et al, reported that from patients with surgical-orthodontic treatment, 20% suffer mandibular excess, 17% have maxillary deficiencies and 10% present both problems.3

Malocclusions are usually clinically significant variations from the normal fluctuation of growth and morphology. They have two basic causes: 1) hereditary or genetic factors and environmental factors; 2) (trauma, physical agents, habits and diseases). However, it is often the result of a complex interaction between several factors that influence growth and development, and it is not always possible to describe a specific etiologic factor.

Of all of these etiological factors there will be some that will influence more in a type of malocclusion than in another. Although both types of malocclusions (skeletal class II and III) may be morphogenetically determined, most of class III problems have very strong inherited components.4

Due to the fact that in the adult patient growth has ceased, our therapeutic options are reduced to two treatment plans, either camouflage or orthognathic surgery. The key question that should be performed during treatment planning for an adult with a skeletal class III malocclusion is to determine the best way to go. The answer must be based on the required orthodontic movements, the stability of these changes and if the likely aesthetic result meets the expectations of the patient, considering that psychological factors are more complex in adult patients seeking orthodontic treatment, and that is why it is extremely important to have a clear idea of what are the wishes and expectations of our patients.5,6

On the other hand, when any other anomaly associated with the dentofacial deformity is present in an adult, such as retained canines, one must be careful in the treatment plan that will be carried out, specially in an interdisciplinary case, as it is necessary to properly plan the times in which to perform each procedure.

The prognosis of orthodontic movement of a retained tooth depends on a variety of factors, such as the position of the impacted tooth with regard to the neighboring teeth, its angle, the distance that the tooth must travel and the possible presence of ankylosis.7 After third molars, the upper canine is the most frequently retained. The incidence of retention of the upper canine has been reported in approximately 2% of patients seeking orthodontic treatment. At the same time, upper canines are often retained 10 times more than the lower ones, appearing with increasing frequency in the palatal aspect and being unilateral retention much more common than the bilateral one.

Surgical procedures included in the surgical-orthodontic treatment of retained canines in patients with skeletal class III malocclusion may be classified according to the age of the patient, the dental development and the possibilities of eruption in: (a) conservative procedure (keep in the dental arch) and (b) late or radical procedure (remove the canine from the maxilla).8

Once the type of procedure to be performed has been determined, considering the characteristics according to the abovementioned classification, the patient must be informed about the treatment plan and its risks/benefits. If a conservative treatment is chosen, it must be carried out during the surgical preparation of the patient, during the presurgical orthodontic phase; on the contrary, if a late or radical treatment is to be made, the clinician should anticipate that an intervention of a prosthetic dentist at the end of orthodontic therapy might be required.9

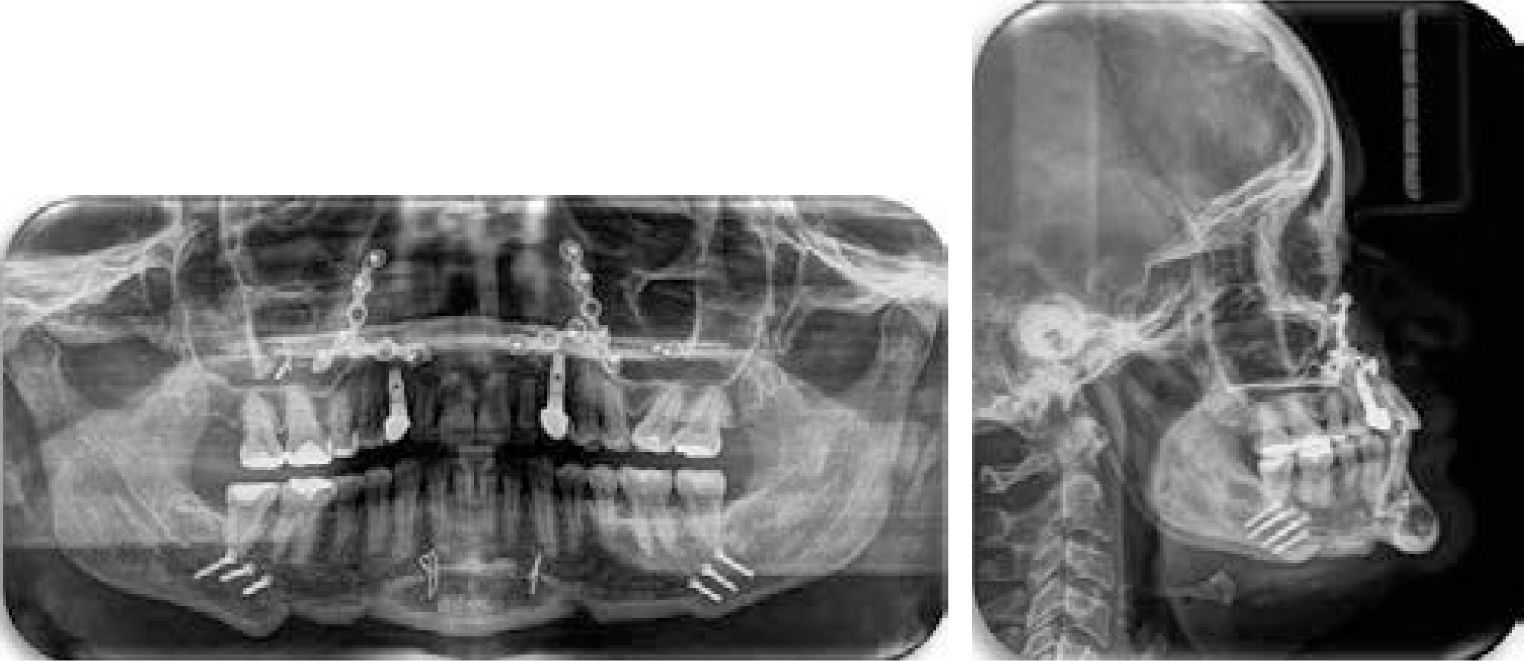

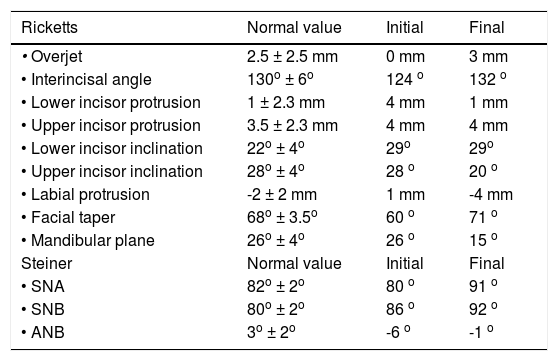

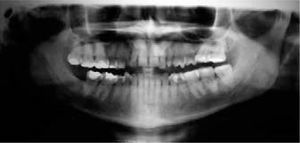

MATERIAL AND METHODSA female patient, 44 years of age, entered the Orthodontics Clinic of the High Specialty Center «Dr. Rafael Lucio». The reason for consultation was: «Because I have baby teeth and I want to close the spaces». According to the clinical analysis the patient was diagnosed as a brachifacial biotype, with an oval-shaped face, a concave profile, sunken middle third, medium lips and straight nose (Figure 1). The intraoral analysis showed a bilateral molar class III, a non-assessable canine class due to the presence of the primary canines, cross bite at the level of the deciduous teeth and an edge-to-edge relationship in the anterior segment, with a overjet of 0 mm, as well as the presence of upper anterior diastemas (Figure 2). Thof e cephalometric and radiographic analysis revealed a skeletal class III due to prognathism, upper incisor proclination, increased mandibular body length, absence of upper and lower third molars, except of the upper right third molar, retained upper canines and no pathologic data in hard tissues (Figures 3and4, Table I).

Initial intraoral photographs. Note the bilateral molar class III, the non-assessable canine class due to the presence of deciduous canines, anterior edge-to-edge bite and crossbite at the level of the primary teeth, 0 mm overjet and the presence of upper anterior diastemas. Patient with mixed dentition.

Initial panoramic radiograph, where the presence of 31 teeth may be observed as well as symmetrical condyles, asymmetric height of the mandibular ramus, 2:1 crown-root ratio, retained upper canines, presence of right upper and lower third molars and absence of left upper and lower third molars.

Cephalometric analysis, Ricketts and Jarabak.

| Ricketts | Normal value | Initial | Final |

|---|---|---|---|

| • Overjet | 2.5 ± 2.5 mm | 0 mm | 3 mm |

| • Interincisal angle | 130o ± 6o | 124 o | 132 o |

| • Lower incisor protrusion | 1 ± 2.3 mm | 4 mm | 1 mm |

| • Upper incisor protrusion | 3.5 ± 2.3 mm | 4 mm | 4 mm |

| • Lower incisor inclination | 22o ± 4o | 29o | 29o |

| • Upper incisor inclination | 28o ± 4o | 28 o | 20 o |

| • Labial protrusion | -2 ± 2 mm | 1 mm | -4 mm |

| • Facial taper | 68o ± 3.5o | 60 o | 71 o |

| • Mandibular plane | 26o ± 4o | 26 o | 15 o |

| Steiner | Normal value | Initial | Final |

| • SNA | 82o ± 2o | 80 o | 91 o |

| • SNB | 80o ± 2o | 86 o | 92 o |

| • ANB | 3o ± 2o | -6 o | -1 o |

It was a multidisciplinary treatment plan, where the specialties of periodontics, orthodontics, and maxillofacial surgery, implantology and oral rehabilitation intervened.

Orthodontic treatment consisted in placement of 0.022” x 0.028” slot MBT appliances, indicating the removal of the third molar, as well as the deciduous canines to try to traction the permanent ones. After eight months of traction of the retained canines, it was determined by radiographic analysis that the movement was very slow and that there was involvement of the adjacent organs, manifested by root resorption, so it was decided, with an informed consent, to surgically remove the retained canines and subsequently rehabilitate them by prosthesis with osseointegrated implants.

Once the presurgical phase of orthodontic treatment was complete, the patient was referred to the Maxillofacial Surgery Service for surgical prediction and planning, by which it was determined to perform: a 5 mm maxillary advancement, 5 mm retroclination of the anterior segment, 9 mm mandibular setback and finally, a descent and advancement of the chin of 4 mm and 7 mm, respectively.

In the postsurgical phase space closure was completed, final coordination of the dental arches took place as well as the settlement and detailing of the occlusion.

Retention was achieved through circumferential retainers on both arches plus fixed retention from lateral incisor to lateral incisor in the upper arch for the subsequent rehabilitation. Total treatment time was 34 months.

RESULTSThrough this treatment an improvement in the maxillo-mandibular relationship was obtained, giving proper projection of the lips and improving the profile; canine guidance was achieved by means of prosthetics. Bilateral molar class I was also obtained as well as coincident midlines, improvement of the smile, a positive overjet and overbite, periodontal health and occlusal function.

Prosthetic rehabilitation was performed to replace the upper canines using implants with fixed prostheses (Figures 5 to 8).

In adult patients who begin orthodontic treatment, special care must be taken in all the details of the malocclusion. Rehabilitation with implants in the anterior region has always been a challenge in the dental practice. The aesthetic and functional maintenance of the implants with the adjacent natural teeth can be particularly difficult. In these cases, appropriate interdisciplinary treatment planning is essential.10

Bailey and Johnston mentioned that historically, skeletal class III malocclusions have been treated only by mandibular setback; however, several studies indicate that bimaxillary procedures have become more frequent in the past 20 years.11,12 Kwon indicates that the skeletal class III malocclusion is often combined with a vertical discrepancy and it has been suggested that vertical changes may affect the amount of mandibular relapse.10,13 However Jākobsone, Moldez, Costa and Proffit stated that several studies established that stability was maintained after vertical changes in the position of the maxilla.14

Proffit mentioned, with respect to the time scale of postsurgical changes, that most of the changes, both skeletal and dento-alveolar, occur within the first six months after surgery, as it may be observed in the patient hereby presented. It is of vital importance that patients that have had dental decompensation, use orthodontic appliances for a few months after orthognathic surgery, to achieve stability in the dentoalveolar and skeletal structures and obtain an overall harmonic result.10

CONCLUSIONSkeletal class III malocclusions, as well as the other dentofacial deformities in adults, are cases of difficult diagnosis and, prognosis, due to the complexity of situations that are present in this group of patients. Suggesting a multidisciplinary treatment in patients with these characteristics who have, in addition, dental limitations (dental absences, periodontal disease, etc.) is of great importance for achieving the objectives set out in a well designed therapeutic plan, as the orthodontics alone would not be capable of restoring dentofacial harmony and thus avoiding success and stability in the treatments. The case of the patient that is reported in the present article complies with this interdisciplinary approach, obtaining results that solve the initial problem and, in this way achieving improvement in dentofacial aesthetics and in function.

Third-year resident of the Orthodontics Specialty.

This article can be read in its full version in the following page: http://www.medigraphic.com/ortodoncia