Disordered eating behaviors (DEB) such as dieting, fasting, laxatives or diuretics abuse, self-induced vomiting and binge eating may lead serious physiological and psychological consequences in individuals. Epidemiological data helps to the understanding of the magnitude of this problem within population; however point prevalence rates and the trend of DEB are still a subject of constant debate. Therefore the aim of this study is to systematically review empirical studies that have estimated the prevalence of DEB in women and provide some methodological considerations for future epidemiological studies. The search of articles was made through MEDLINE and SCIENCE DIRECT databases from 2000 to 2013. According to inclusion and exclusion criteria 20 studies were reviewed. Results yielded that the point prevalence range of dieting (0.6–51.7%), fasting (2.1–18.5%) and binge eating (1.2–17.3%) are higher than purgative behaviors (0–11%). However finding a trend in DEB over time was difficult since methodologies were significantly different. Methodological considerations for future research in DEB are proposed.

Las conductas alimentarias de riesgo (CAR) de los trastornos alimentarios, tales como dieta, ayuno, abuso de laxantes o diuréticos, vómito autoinducido y atracón, pueden causar graves consecuencias fisiológicas y psicológicas en el individuo. Los datos epidemiológicos ayudan a la comprensión de la magnitud de este problema en la población, sin embargo las tasas de prevalencia puntual y la tendencia de las CAR aún son tema de constante debate. Por lo tanto, el objetivo del presente estudio es revisar sistemáticamente estudios empíricos que estimen la prevalencia de las CAR en mujeres y proveer consideraciones metodológicas para futura investigación epidemiológica. La búsqueda de artículos fue a través de las bases de datos de MEDLINE y SCIENCEDIRECT de 2000 a 2013. Con base en los criterios de inclusión y exclusión 20 estudios fueron analizados. Los resultados arrojaron que el rango de la prevalencia puntual para dieta (0,6-51,7%), ayuno (2,1-18,5%) y atracón (1,2-17,3%) son mayores que el de las conductas purgativas (0-11%). Sin embargo, fue difícil encontrar una tendencia en las CAR a través del tiempo debido a que las metodologías utilizadas fueron significativamente diferentes. Se proponen consideraciones metodológicas para futuras investigaciones en CAR.

Eating disorders (ED) with higher prevalence rates are anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED) according to the 5th version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ([DSM-5] APA, 2013). In the last two decades studies about epidemiology on ED have increased significantly, however it is worth to point out that the three basic frequency measures in this kind of studies are incidence, prevalence and mortality. Incidence expresses the volume and acceleration of new cases —disease or disorder—over a specific population and period, usually one year (Striegel-Moore, Franko, & Ach, 2006); prevalence rates refer to the number of individuals in relation to the total population that suffer a disease or disorder in a specific time (Moreno, López, & Hernández, 2007); mortality rates point out the number of deaths caused by a specific disease. This measure is often used as an indicator of illness severity (Rothman, 2002). All these measures yield important information that helps us to characterize ED in terms of risk, occurrence and trends over time; however this study will focus exclusively on prevalence, because this measure is essential in planning health services, designation of economical resources and administration of medical care facilities (Hoek & van Hoeken, 2003; Kleinbaum, Kupper, & Morgenstern, 1982). According to epidemiological literature there are different types of prevalence, (a) point prevalence is a particular assessment in certain point in time; (b) period prevalence is the percentage of cases established within a period of time (usually 1-year period); and (c) lifetime prevalence is defined as the number of individuals that at any time have experienced a disorder (Hoek & van Hoeken, 2003; Hunter & Risebro, 2011).

Lifetime prevalence rates for AN, BN and BED are 0.9%, 1.5% and 3.5% among women and 0.3%, 0.5% and 2.0% for men respectively (, Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007). Also the category called “Other Specified Eating Disorders (OSED)” included in DSM-5, which is applied when the individual does not meet the full criteria for any of the ED, has a lifetime prevalence of 4–5% (Le Grange, Swanson, Crow, & Merikangas, 2012). Nevertheless it has been documented that disordered eating behaviors (DEB) are more common among community sample, such as, restrictive dieting, fasting, self-induced vomiting, abuse of laxatives and/or diuretics and binge eating (Garner, 2008; Tam, Ng, Man, & Young, 2007). These behaviors are important risk factors because they have physiological complications, for example, delayed linear growth and delayed puberty (Daee et al., 2002); dental erosion, mouth and esophagus ulcers and in severe cases the onset of esophagus cancer (Matsha et al., 2006; Mitchell, Pomeroy, & Adson, 1997); or digestive and urinary abnormalities (Mitchell et al., 1997). However the psychological consequences are as dangerous or even more than physiological complications since individuals who present them at early and late adolescence not only are more likely to develop an ED in adulthood, but also because these individuals are more susceptible to engage on depression, low self-esteem, anxiety, substance abuse or suicide attempts (Garner & Keiper, 2010; Kotler, Cohen, Davies, Pine, & Walsh, 2001; Nunes, Barros, Anselmo, Camey, & Mari, 2003; Preti, Rocchi, Sisti, Camboni, & Miotto, 2011; Tylka & Mezydlo, 2004).

Based on epidemiological research, in South Australia, Hay, Mond, Buttner, and Darby (2008) assessed the prevalence of DEB with women in two moments, the first in 1995 (M=43.4, SD=19.2 years) and the second in 2005 (M=45.1, SD=24.5 years) finding a point prevalence of 3.2% and 7.5% in binge eating; 1.3% and 2.1% in purging behaviors; 2.5% and 5.2% in strict dieting, respectively. These data give evidence of an increase in prevalence of DEB over time.

A set of studies carried out by Keel and colleagues evaluated, in a longitudinal study, the point prevalence of DEB (Heatherton, Mahamedi, Striepe, Field, & Keel, 1997), BN symptoms (Keel, Heatherton, Dorer, Joiner, & Zalta, 2006) and BN and OSED of BN (Keel, Gravener, Joiner, & Haedt, 2010). They reported that purging behaviors—defined as the use of vomiting, laxatives or diuretics to control weight—prevalence were 5.1% in 1982, 3.5% in 1992 and 4.3% in 2002, concluding that these behaviors did not change significantly across cohorts; however point prevalence in binge eating (29.2% in 1982, 20% in 1992 and 14.8% in 2002) and fasting (19.6% in 1982, 12.7% in 1992 and 11.1% in 2002) decreased significantly from 1982 to 2002 (Keel et al., 2006).

When there is a marked uncertainty in a specific topic, such as the prevalence of DEB, it is recommended to carry out a systematic review since this kind of studies gather relevant, valid and reliable information selected under rigorous methodological criteria that allow to discuss inconsistencies among studies to redesign and improve future research (Beltrán, 2005). In this sense, some literature reviews have tried to explain the epidemiology of ED (from 1981 to 2002; Hoek & van Hoeken, 2003), of OSED (among 1980–2003; Chamay-Weber, Narring, & Michaud, 2005), and combining ED and OSED but only with Spanish population (from 2000 to 2010; Peláez, Raich, & Labrador, 2010). Finally to our knowledge there are two extent studies that comprised ED, OSED and DEB that analyzed studies of the last three decades (Jacobi, Abascal, & Taylor, 2004) and one of them only reviewed Japanese publications (Chisuwa & O’Dea, 2010).

Based on these background, we can summarize that (1) DEB are more common than full entities; (2) empirical studies yield inconsistent prevalence rates and (3) literature reviews limit their analysis to specific population or full entities, therefore the aim of this paper is to systematically review empirical studies that have provided estimates of prevalence of the DEB in women, specifically on restrictive dieting, fasting, laxatives or diuretics abuse, self-induced vomiting and/or binge eating. Particular attention will be paid to methodological differences across studies since these may be linked to discrepancies in the results reported. Analysis of strengths and limitations of these studies will be followed with recommendations for future studies of DEB.

Several hypotheses emerged for this review: (a) different type of prevalence (point, period and lifetime) will yield diverse rates; (b) methodological differences will yield different rates of prevalence and (c) restrictive dieting and binge eating will be the most prevalent DEB.

MethodAccording to PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009) on February 2013, a search of articles was carried out through MEDLINE and SCIENCE DIRECT databases, using different combinations of the following key words contained in the title, abstract and/or within the article's keywords: eating disorders, eating disorders not otherwise specified (term known as OSED in DSM-5), anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, prevalence and women. Considering the dates of previous reviews for the current study were eligible studies published between January 2000 and January 2013.

To choose the studies for this review, the first two authors determined the relevance and adequacy of each eligible paper according the following selection criteria:

Inclusion criteria: (a) studies must be based on community sample and (b) studies must assess at least one of the behaviors of interest (restrictive dieting, fasting, misuse of laxatives and diuretics self-induced vomiting and/or binge eating).

Exclusion criteria: (a) studies based on clinical samples or only in male population; (b) assessment of exclusively other epidemiological measures (e.g. incidence or mortality); (c) papers written in any other language than English or Spanish and (d) dissertations.

Each article was analyzed using data extraction sheets, based on the principles proposed by Sánchez-Sosa (2004). The data extraction sheets included the following variables: (a) sample (geographical zone, age/gender, sample selection, sample size/sample-size power/response rate); (b) research design; (c) instruments; and (d) prevalence rates.

The first search yielded a total of 2024 abstracts, 1711 were excluded for: being related with the medical field, going deeply in psychiatric comorbidity or intervention programs, evaluate cognitions associated to eating disorders such as body dissatisfaction, perfectionism, thin ideal internalization, etc. Of the remaining 313 articles, 217 were excluded because: only incidence rates were reported, sample included only men, pregnant, or clinical cases, were dissertations, were written in a different language than Spanish or English and were reviews. Of the remaining 96 studies, 76 were excluded for: reporting only AN, BN and/or OSED prevalence rates. The 20 remaining studies that met inclusion criteria fluctuated from 2001 to 2010.

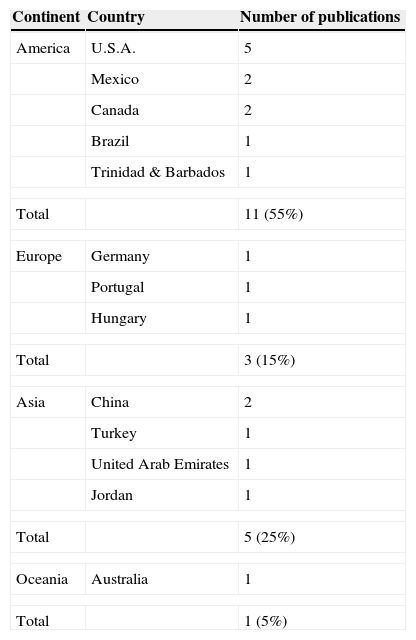

Data analysisSampleGeographical zoneMost of the studies were from United States (25%, n=5), followed by Canada, China and Mexico (10%, n=2 each country). The remaining studies were carried out in nine different countries (see Table 1).

Classification of studies according to the country where they were published.

| Continent | Country | Number of publications |

|---|---|---|

| America | U.S.A. | 5 |

| Mexico | 2 | |

| Canada | 2 | |

| Brazil | 1 | |

| Trinidad & Barbados | 1 | |

| Total | 11 (55%) | |

| Europe | Germany | 1 |

| Portugal | 1 | |

| Hungary | 1 | |

| Total | 3 (15%) | |

| Asia | China | 2 |

| Turkey | 1 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | |

| Jordan | 1 | |

| Total | 5 (25%) | |

| Oceania | Australia | 1 |

| Total | 1 (5%) | |

The studies were from two different settings; 16 (80%) from educational institutions, and 4 (20%) were from home-settings (Hay et al., 2008; Hudson et al., 2007; Nunes et al., 2003; Westenhoefer, 2001).

Age and genderMore than a half of the research papers (55%, n=11) worked with adolescent samples, which means participants aged among 11–19 years, 20% (n=4) of the studies included adults older than 19 years old (Hay et al., 2008; Hudson et al., 2007; Kiziltan, Karabudak, Ünver, Sezgin, & Ünal, 2006; Westenhoefer, 2001), and 25% (n=5) combined two different types of sample, including adolescents and young adults, going from 10 to 29 years old (Machado, Machado, Gonçalves, & Hoek, 2007; Neumark-Sztainer, Wall, Eisenberg, Story, & Hannan, 2006; Nunes et al., 2003; Tam et al., 2007; Tölgyes & Nemessury, 2004). Regarding to gender, in this review most of studies included men and women (60%, n=12); however it is important to underline that given the purpose of the present review we limit the “Findings” section to only female prevalence rates, since this population present the highest risk to develop DEB (APA, 2013).

Sample selectionFrom the 20 articles, 12 (60%) used randomized samples, 4 (20%) used convenience samples, and other 4 (20%) did not describe the type of sampling method they utilized (see Tables 2 and 3).

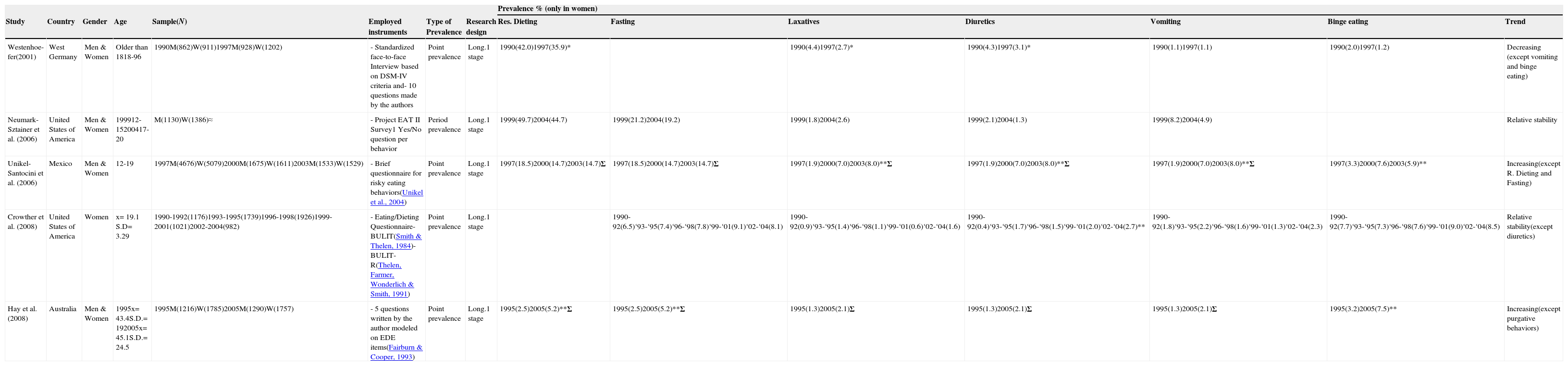

Longitudinal studies.

| Prevalence % (only in women) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Country | Gender | Age | Sample(N) | Employed instruments | Type of Prevalence | Research design | Res. Dieting | Fasting | Laxatives | Diuretics | Vomiting | Binge eating | Trend |

| Westenhoe-fer(2001) | West Germany | Men & Women | Older than 1818-96 | 1990M(862)W(911)1997M(928)W(1202) | - Standardized face-to-face Interview based on DSM-IV criteria and- 10 questions made by the authors | Point prevalence | Long.1 stage | 1990(42.0)1997(35.9)* | 1990(4.4)1997(2.7)* | 1990(4.3)1997(3.1)* | 1990(1.1)1997(1.1) | 1990(2.0)1997(1.2) | Decreasing (except vomiting and binge eating) | |

| Neumark-Sztainer et al. (2006) | United States of America | Men & Women | 199912-15200417-20 | M(1130)W(1386)≈ | - Project EAT II Survey1 Yes/No question per behavior | Period prevalence | Long.1 stage | 1999(49.7)2004(44.7) | 1999(21.2)2004(19.2) | 1999(1.8)2004(2.6) | 1999(2.1)2004(1.3) | 1999(8.2)2004(4.9) | Relative stability | |

| Unikel-Santocini et al. (2006) | Mexico | Men & Women | 12-19 | 1997M(4676)W(5079)2000M(1675)W(1611)2003M(1533)W(1529) | - Brief questionnaire for risky eating behaviors(Unikel et al., 2004) | Point prevalence | Long.1 stage | 1997(18.5)2000(14.7)2003(14.7)Σ | 1997(18.5)2000(14.7)2003(14.7)Σ | 1997(1.9)2000(7.0)2003(8.0)**Σ | 1997(1.9)2000(7.0)2003(8.0)**Σ | 1997(1.9)2000(7.0)2003(8.0)**Σ | 1997(3.3)2000(7.6)2003(5.9)** | Increasing(except R. Dieting and Fasting) |

| Crowther et al. (2008) | United States of America | Women | x= 19.1 S.D= 3.29 | 1990-1992(1176)1993-1995(1739)1996-1998(1926)1999-2001(1021)2002-2004(982) | - Eating/Dieting Questionnaire- BULIT(Smith & Thelen, 1984)- BULIT-R(Thelen, Farmer, Wonderlich & Smith, 1991) | Point prevalence | Long.1 stage | 1990-92(6.5)‘93-‘95(7.4)‘96-‘98(7.8)‘99-‘01(9.1)‘02-‘04(8.1) | 1990-92(0.9)‘93-‘95(1.4)‘96-‘98(1.1)‘99-‘01(0.6)‘02-‘04(1.6) | 1990-92(0.4)‘93-‘95(1.7)‘96-‘98(1.5)‘99-‘01(2.0)‘02-‘04(2.7)** | 1990-92(1.8)‘93-‘95(2.2)‘96-‘98(1.6)‘99-‘01(1.3)‘02-‘04(2.3) | 1990-92(7.7)‘93-‘95(7.3)‘96-‘98(7.6)‘99-‘01(9.0)‘02-‘04(8.5) | Relative stability(except diuretics) | |

| Hay et al. (2008) | Australia | Men & Women | 1995x= 43.4S.D.= 192005x= 45.1S.D.= 24.5 | 1995M(1216)W(1785)2005M(1290)W(1757) | - 5 questions written by the author modeled on EDE items(Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) | Point prevalence | Long.1 stage | 1995(2.5)2005(5.2)**Σ | 1995(2.5)2005(5.2)**Σ | 1995(1.3)2005(2.1)Σ | 1995(1.3)2005(2.1)Σ | 1995(1.3)2005(2.1)Σ | 1995(3.2)2005(7.5)** | Increasing(except purgative behaviors) |

Res. Dieting=Restrictive Dieting; M=Men; W=Women; x=Mean age; S.D=Standard Deviation; Long.=Longitudinal; *=Prevalence is significantly lower than time one (p<.05); **=Prevalence is significantly higher than time one (p<.05); ≈=Same subjects were followed up; BULIT=Bulimia Test; BULIT-R=Bulimia Test Revised; EDE=Eating Disorder Examination; ∑=Authors collapsed into one category more than one restrictive or purgative behavior.

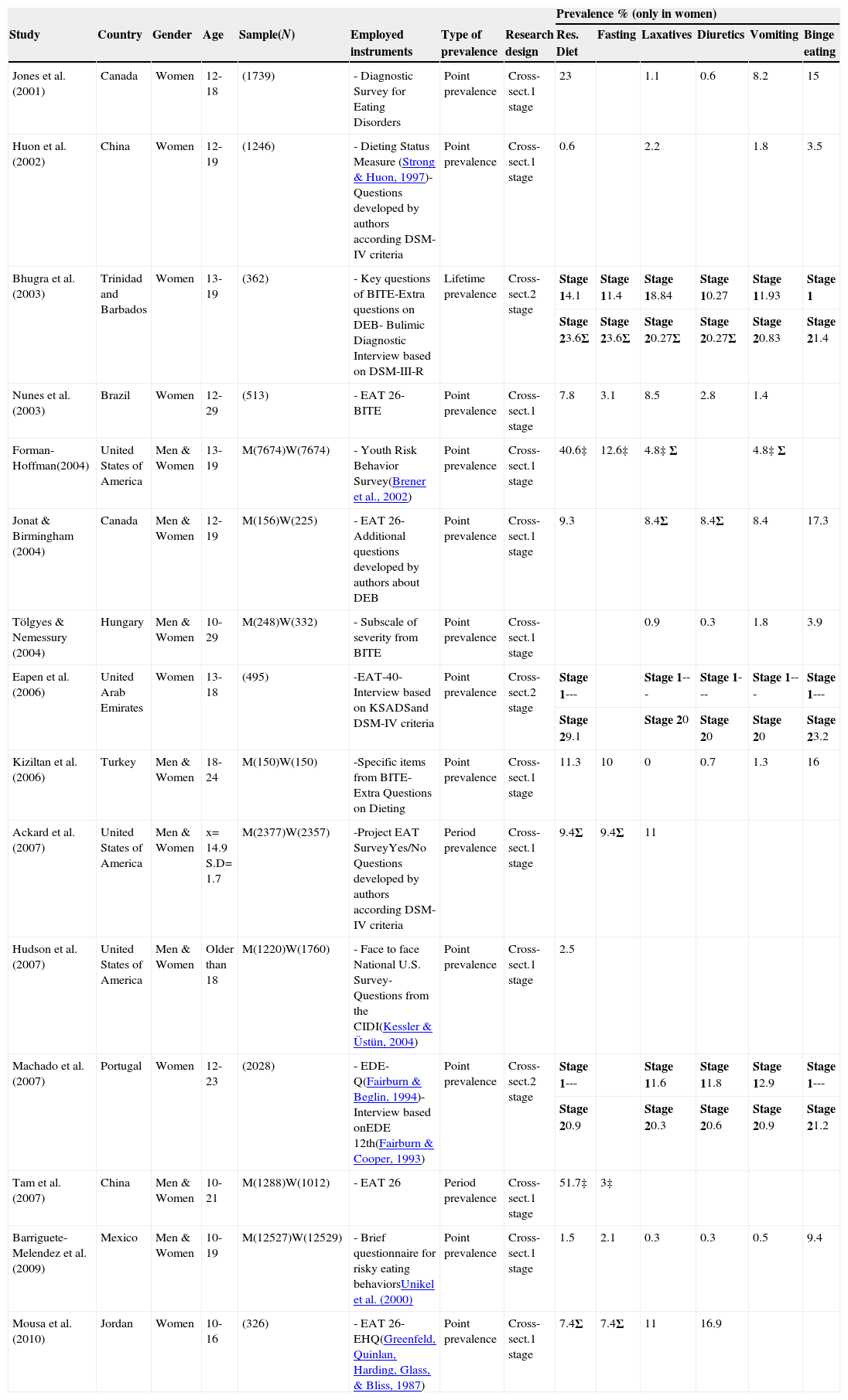

Cross-sectional studies.

| Prevalence % (only in women) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Country | Gender | Age | Sample(N) | Employed instruments | Type of prevalence | Research design | Res. Diet | Fasting | Laxatives | Diuretics | Vomiting | Binge eating |

| Jones et al.(2001) | Canada | Women | 12-18 | (1739) | - Diagnostic Survey for Eating Disorders | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 23 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 8.2 | 15 | |

| Huon et al. (2002) | China | Women | 12-19 | (1246) | - Dieting Status Measure (Strong & Huon, 1997)-Questions developed by authors according DSM-IV criteria | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 0.6 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 3.5 | ||

| Bhugra et al. (2003) | Trinidad and Barbados | Women | 13-19 | (362) | - Key questions of BITE-Extra questions on DEB- Bulimic Diagnostic Interview based on DSM-III-R | Lifetime prevalence | Cross-sect.2 stage | Stage 14.1 | Stage 11.4 | Stage 18.84 | Stage 10.27 | Stage 11.93 | Stage 1 |

| Stage 23.6Σ | Stage 23.6Σ | Stage 20.27Σ | Stage 20.27Σ | Stage 20.83 | Stage 21.4 | ||||||||

| Nunes et al. (2003) | Brazil | Women | 12-29 | (513) | - EAT 26- BITE | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 7.8 | 3.1 | 8.5 | 2.8 | 1.4 | |

| Forman-Hoffman(2004) | United States of America | Men & Women | 13-19 | M(7674)W(7674) | - Youth Risk Behavior Survey(Brener et al., 2002) | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 40.6‡ | 12.6‡ | 4.8‡ Σ | 4.8‡ Σ | ||

| Jonat & Birmingham (2004) | Canada | Men & Women | 12-19 | M(156)W(225) | - EAT 26- Additional questions developed by authors about DEB | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 9.3 | 8.4Σ | 8.4Σ | 8.4 | 17.3 | |

| Tölgyes & Nemessury (2004) | Hungary | Men & Women | 10-29 | M(248)W(332) | - Subscale of severity from BITE | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 3.9 | ||

| Eapen et al. (2006) | United Arab Emirates | Women | 13-18 | (495) | -EAT-40- Interview based on KSADSand DSM-IV criteria | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.2 stage | Stage 1--- | Stage 1--- | Stage 1--- | Stage 1--- | Stage 1--- | |

| Stage 29.1 | Stage 20 | Stage 20 | Stage 20 | Stage 23.2 | |||||||||

| Kiziltan et al.(2006) | Turkey | Men & Women | 18-24 | M(150)W(150) | -Specific items from BITE-Extra Questions on Dieting | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 11.3 | 10 | 0 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 16 |

| Ackard et al.(2007) | United States of America | Men & Women | x= 14.9 S.D= 1.7 | M(2377)W(2357) | -Project EAT SurveyYes/No Questions developed by authors according DSM-IV criteria | Period prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 9.4Σ | 9.4Σ | 11 | |||

| Hudson et al.(2007) | United States of America | Men & Women | Older than 18 | M(1220)W(1760) | - Face to face National U.S. Survey- Questions from the CIDI(Kessler & Üstün, 2004) | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 2.5 | |||||

| Machado et al. (2007) | Portugal | Women | 12-23 | (2028) | - EDE-Q(Fairburn & Beglin, 1994)- Interview based onEDE 12th(Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.2 stage | Stage 1--- | Stage 11.6 | Stage 11.8 | Stage 12.9 | Stage 1--- | |

| Stage 20.9 | Stage 20.3 | Stage 20.6 | Stage 20.9 | Stage 21.2 | |||||||||

| Tam et al. (2007) | China | Men & Women | 10-21 | M(1288)W(1012) | - EAT 26 | Period prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 51.7‡ | 3‡ | ||||

| Barriguete-Melendez et al. (2009) | Mexico | Men & Women | 10-19 | M(12527)W(12529) | - Brief questionnaire for risky eating behaviorsUnikel et al. (2000) | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 1.5 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 9.4 |

| Mousa et al. (2010) | Jordan | Women | 10-16 | (326) | - EAT 26- EHQ(Greenfeld, Quinlan, Harding, Glass, & Bliss, 1987) | Point prevalence | Cross-sect.1 stage | 7.4Σ | 7.4Σ | 11 | 16.9 | ||

Res. Diet=Restrictive Dieting; M=Men; W=Women; KSADS=Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; x=Mean age; S.D=Standard Deviation; CIDI=World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview; EDE-Q=Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire; EDE 12th=Eating Disorder Examination 12th edition; EHQ=Eating Habits Questionnaire; ‡=Results include men and women; ∑=Authors collapsed into one category more than one restrictive or purgative behavior.

In this review it was observed that 75% (n=15) utilized a sample size less than 3000, 15% (n=3) included a sample size over 3000 and less than 10,000 (Ackard, Fulkerson, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2007; Hay et al., 2008; Unikel-Santocini, Bojórquez-Chapela, Villatoro-Velázquez, Fleiz-Bautista, & Medina-Mora, 2006) finally 10% (n=2) of the articles considered samples over 10,000 participants (Barriguete-Meléndez et al., 2009; Forman-Hoffman, 2004). According to sample-size power, only two (10%) of the 20 articles, reported this analysis (Barriguete-Meléndez et al., 2009; Tam et al., 2007). Regard response rate reported by authors, 70% (n=14) stated a good response rate, 20% (n=4) mentioned that they did not reach a good parameter and 10% (n=2) did not mention any response rate.

Research designThe majority of studies (n=12, 60%) reviewed used a cross-sectional one-stage procedure to evaluate DEB—using either self-report questionnaires or interview. Cross-sectional of two-stage procedure was used by 15% (n=3) of the studies (Bhugra, Mastrogianni, Maharajh, & Harvey, 2003; Eapen, Mabrouk, & Bin-Othman, 2006; Machado et al., 2007; see Table 3). On the other hand a significant minority of the studies (n=5 or 25%) employed a longitudinal one-stage procedure where follow-ups varied from 5 to 15 years (see Table 2). None study used a two-stage longitudinal procedure.

InstrumentsTables 2 and 3 show the different measures utilized to evaluate DEB. From the 20 studies reviewed, five (25%) employed only self-report questionnaires (Crowther, Armey, Luce, Dalton, & Leahey, 2008; Mousa, Al-Domi, Mashal, & Jibril, 2010; Nunes et al., 2003; Tam et al., 2007; Tölgyes & Nemessury, 2004). The screening instrument utilized most frequently among these studies was the Eating Attitudes Test, four studies employed the 26-item version and one the 40-item version (Garner & Garfinkel, 1979; Garner, Olmsted, Bohr, & Garfinkel, 1982). The Bulimic Investigatory Test, Edinburgh ([BITE], Henderson & Freeman, 1987) was utilized by four studies (20%).

Four studies (Bhugra et al., 2003; Eapen et al., 2006; Machado et al., 2007; Westenhoefer, 2001) identified DEB by self-report measures and by clinical interview. The interviews utilized were: Those based on the 3rd Rev. ed. or the 4th ed. of the DSM (APA, 1987, 1994), the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE, 12th ed; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS).

A combined system of screening instruments plus questions ex professo developed by the authors was carried out in three investigations (Huon, Mingyi, Oliver, & Xiao, 2002; Jonat & Birmingham, 2004; Kiziltan et al., 2006).

Finally eight investigations (40%) assessed DEB through National Surveys but only three were specialized in ED being the most common Project EAT Survey (Ackard et al., 2007; Jones, Bennett, Olmsted, Lawson, & Rodin, 2001; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006). The other five surveys were focused in different aspects such as Drug and Alcohol in Student Population, Youth Risk Behaviors and National Health but questions related to DEB were embedded in these surveys.

PrevalenceType of prevalenceThe majority of studies (n=16, 80%) assessed point prevalence of DEB, three studies (15%; Ackard et al., 2007; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006; Tam et al., 2007) evaluated period prevalence and one study (5%; Bhugra et al., 2003) calculated lifetime prevalence (see Tables 2 and 3). Although for comparison purposes will be suitable to analyze studies with same type of prevalence, it was decided to include all investigations for the analysis, since period and lifetime prevalence studies were insufficient to make comparisons among them, therefore it is suggested that the reader take into account that four studies that estimated different type of prevalence were included in the present analysis.

Prevalence ratesFor better understanding of the data studies were classified according to the research design, of the 20 papers reviewed five were longitudinal and 15 were cross-sectional. This was determined since longitudinal studies may suggest a trend of the DEB while cross-sectional studies only report data in one specific point of the time, therefore to compare data from these two type of studies will be spurious. Also it is worth to highlight that in the analysis section when the term “paper-and-pencil instruments” is mentioned, it means that tests such as self-report questionnaires and/or surveys and/or ex professo questions were included to assess DEB.

Prevalence of restrictive dietingEleven of 15 cross-sectional studies reported this behavior; eight of them used one-stage procedure. From these latter eight, five were from America and three from Asia. All studies from the American continent utilized paper-and-pencil instruments, the highest prevalence rates was reported in one study from United States being 40.6%, followed by two studies of Canada that reported 9.3% and 23.0%. One study from Mexico reported 1.5% and one study from Brazil reported 7.8%. Otherwise studies from Asia used paper-and-pencil instruments yielding the following prevalence rates, 51.7% and 0.6% in China and 11.3% in Turkey (see Table 3).

Table 3 shows three two-stage studies. Bhugra et al. (2003) reported a prevalence rate in restrictive behaviors (dieting and fasting) of 3.6% in a Trinidadian population; Eapen et al. (2006) documented in women from United Arab Emirates a prevalence of 9.1%; and Machado et al. (2007) stated a prevalence of 0.9% in Portuguese population. Even though these studies used similar methodologies the prevalence rates were substantially different.

Paying special attention on longitudinal studies (n=5), it was observed that four of them assessed restrictive dieting. Only one study (Westenhoefer, 2001) used face-to-face interview with German population, reporting a significant decrease over the period surveyed (1990–1997) going from 42.0% to 35.9% (p<.05). Contrary, Hay et al. (2008) used paper-and-pencil instruments, they clustered restrictive dieting and fasting, founding prevalence rates of 2.5% in 1995 and 5.2% in 2005 (p<.002) in Australian population. However two studies suggested a relative stability over time using paper-and-pencil instruments, one from United States (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006) and the other from Mexico (Unikel-Santocini et al., 2006), the latter study collapsed dieting and fasting in one category (see Table 2).

FastingFive of 15 cross-sectional studies assessed this behavior; four of them used one-stage procedure. From these latter four, three were from America and one from Asia. All studies utilized paper-and-pencil instruments, the highest prevalence rates were reported in one study of United States (12.6%) and one from Turkey (10.0%), and the lowest prevalence rates were reported by Brazil (3.1%) and Mexico (2.1%; see Table 3).

The study of Bhugra et al. (2003) was the only that used a two-stage procedure to analyze restrictive behaviors (dieting and fasting) founding a prevalence rate of 3.6% in a Trinidadian population (see Table 3).

Of five longitudinal studies four assessed fasting. A statistical increase over time in this behavior was reported by Hay et al. (2008) showing prevalence rates of restrictive behaviors (restrictive dieting and fasting) from 2.5% in 1995 to 5.2% in 2005 (p<0.001) in Australian population. The other three longitudinal studies with American and Mexican population (Crowther et al., 2008; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006; Unikel-Santocini et al., 2006) noted a fairly stability over the years (see Table 2).

Binge eatingTwelve of 15 cross-sectional studies reported this behavior; nine of them used one-stage procedure. From these latter nine, five were from America, three from Asia and one from Europe. All studies from the American continent utilized paper-and-pencil instruments, the highest prevalence rates were reported in two studies from Canada being 17.3% and 15.0%, besides two studies were carried out in United States reporting 11.0% and 2.5% and finally one study from Mexico reported 9.4%. Otherwise studies from Asia used paper-and-pencil instruments yielding the following prevalence rates, 16.9% in Jordan, 16.0% in Turkey and 3.5% in China. There is one study from Europe, reporting 3.9% in Hungarian population using paper-and-pencil instruments (see Table 3).

Three of 15 studies used a two-stage procedure. Bhugra et al. (2003) reported a prevalence rate of 1.4% in a Trinidadian population; Eapen et al. (2006) documented in women from United Arab Emirates a prevalence of 3.2%; and Machado et al. (2007) stated a prevalence of 1.2% in Portuguese population (see Table 3).

Of five longitudinal studies four assessed binge eating. A statistical increase over time in this behavior was reported in two studies using paper-and-pencil instruments: Unikel-Santocini et al. (2006) reported prevalence rates from 3.3% to 5.9% in Mexican population and Hay et al. (2008), from 3.2% to 7.5% (p<0.001) in Australian population. The other two longitudinal studies with American and German population (Crowther et al., 2008; Westenhoefer, 2001) noted a fairly stability over the years (see Table 2).

Purgative behaviorsSix of 20 studies clustered the self-induced vomiting, abuse of laxatives and diuretics in one category, therefore the prevalence rates of these behaviors individually is uncertain, consequently the prevalence analysis was made only with those studies who reported prevalence rates of each behavior and not with those who combined more than one behavior, calling them purgative behaviors.

Abuse of laxativesEight of 15 cross-sectional studies assessed the use of laxatives; six of them used one-stage procedure. From these latter six, three of them were from America, two from Asia and one from Europe. All studies from the American continent utilized paper-and-pencil instruments, the highest prevalence rates were reported by Brazil with 8.5%, while Mexico and Canada reported prevalence rates equal or less than 1.1%. Otherwise studies from Asia used paper-and-pencil instruments yielding the following prevalence rates, 2.2% in China and 0% in Turkey. There is one study from Europe performed in Hungary reporting 0.9% with paper-and-pencil instruments (see Table 3).

Three of twenty studies used a two-stage procedure. Bhugra et al. (2003) reported a prevalence rate of 0.3% in a Trinidadian population; Eapen et al. (2006) documented in women from United Arab Emirates a prevalence of 0%; and Machado et al. (2007) stated a prevalence of 0.3% in Portuguese population (see Table 3).

Of five longitudinal studies three assessed the use of laxatives. One study from Germany reported a decreasing trend (4.4% in 1990 and 2.7% in 1997), in contrast, two studies from United States found a fairly stability over the years (see Table 2).

Abuse of diureticsSeven of 15 cross-sectional studies assessed this behavior; five of them used one-stage procedure. From these latter five, three were from America, one from Europe and one from Asia. All studies utilized paper-and-pencil instruments, the highest prevalence rate was reported by Brazil with 2.8%, while prevalence rates of Mexico, Canada, Hungary and Turkey ranged among 0.3% and 0.7%. On the other hand two studies used a two-stage procedure. The first performed in United Arab Emirates documented a prevalence of 0% (Eapen et al., 2006) and the second in Portugal stated a prevalence rate of 0.6% (Machado et al., 2007; see Table 3).

Of five longitudinal studies three assessed the use of diuretics. One study from Germany reported a decreasing trend (4.3% in 1990 and 3.1% in 1997), in contrast, one study from United States found a fairly stability over five-years with prevalence rates of 2.1% in 1999 and 1.3% in 2004 (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006), and the other found an increase in prevalence rates ranging among 0.4% to 2.7% in a twelve-year period (Crowther et al., 2008; see Table 2).

Self-induced vomitingTwelve of 15 cross-sectional studies evaluated this behavior; nine of them used one-stage procedure. From these latter nine, four were from America, one from Europe and four from Asia. All studies utilized paper-and-pencil instruments, the highest prevalence rate were reported by three studies, Mousa et al. (2010) reported a prevalence rate of 11.0% in Jordanian population, Jones et al. (2001) with 8.2% and Jonat and Birmingham (2004) with 8.4% these latter two prevalence rates in Canadian population. In contrast Mexico, Brazil, Hungary, Turkey and China showed range prevalence among 0.5–3.0% (see Table 3).

Three studies used a two-stage procedure. In Trinidadian (Bhugra et al., 2003), Arab (Eapen et al., 2006) and Portuguese (Machado et al., 2007) population prevalence rates were lower than 1.0% (see Table 3).

Of five longitudinal studies three assessed vomiting. All of them found a fairly stability over the years, one of them (Westenhoefer, 2001) with a standardized face-to-face interview found a prevalence rate of 1.1% in 1990 and 1997. The other two were carried out with American population using paper-and-pencil instruments, Neumark-Sztainer et al. (2006) stated in a five-year period prevalence rates of 8.2% in 1999 and 4.9% in 2004 and Crowther et al. (2008) reported prevalence rates that range among 1.8–2.3% in a twelve-year period (see Table 2).

To summarize the information above it is possible to assume that longitudinal studies suggested a stable trend for restrictive dieting, fasting, use of laxatives and vomiting since there were no statistical differences in prevalence rates over the periods assessed, while the suggested trend of binge eating and use of diuretics was variable according with the statistical analysis reported.

Considering the prevalence rates yielded for the 20 studies it was observed that restrictive dieting was the DEB with the highest prevalence rate, followed by fasting and binge eating, whereas purgative behaviors showed the lowest prevalence rates.

DiscussionThe main objective of the present paper was to systematically review empirical studies that have provided estimates of prevalence of the DEB in women, as well as make some recommendations for future epidemiological studies of DEB.

This review found inconsistent results among studies analyzed, however this is relevant since systematic reviews provide a general view of how have been investigated the prevalence of DEB. There are several confounding factors that may be responsible for these conflicting findings. One explanation is that different types of prevalence were reported, supporting the first hypothesis of this review which was: different type of prevalence (point, period and lifetime) will yield diverse rates. It is common that prevalence rates are consider just as one general epidemiological measure, however this may have different types and therefore different objectives. In this literature review 80% of the studies reported the point prevalence of DEB, this is reasonable since in ED field the temporality and frequency in these behaviors (at least during the past three months and twice a week according with DSM-5) are crucial data to determine the clinical relevance, therefore the point prevalence considers this aspect and gives a general view about the presence or absence of these behaviors among the population, allowing health services to provide facilities more attached to the necessities of the society. Hence it is recommended that both reader and researcher identify which kind of prevalence will be studied, since the unclearness in this aspect may affect the methodology, the results and main conclusions of the research, yielding prevalence rates over or sub-estimated not only of DEB but of any disorder.

There is a considerable debate around the prevalence of DEB, since it is difficult to determine if these have rise, decrease or remained stable over time, this dispute is not only related to type of prevalence issues, but also to differences in methodologies among studies such as sample features, research design and instruments, therefore the second hypothesis that was methodological differences will yield different rates of prevalence, was accepted. For instance, large samples are important in epidemiological studies to be able to generalize findings; in this review 35% of the papers reported less than 1000 participants. Although there is not a consensus about what does it mean “large samples”, Jacobi, Hayward, de Zwaan, Kraemer, and Agras (2004) have suggested for better estimations of prevalence rates, a sample size of at least 3000 subjects within a community-based study. However the size is not enough to assure the representativeness of the sample, also it is necessary to consider the method of sample selection and the response rate. The gold standard procedure in epidemiology for sample selection is the randomized methods, and Punch (2003) established that good response rates in face to face surveys goes from 80% to 85%, questionnaires sent by mail starting from 60%, by online of 30% or more and in classroom by paper starting from 50%. According to these assumptions it is worth to highlight that in this review most of studies accomplished with these two latter criteria, however these criteria must be achieved in all epidemiological researches, since these are key features that will reflect more real and certain prevalence rates among the population studied.

Regarding to research design, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies yield relevant information, for instance, cross-sectional studies allow to predict strategies for prevention and intervention programs; however longitudinal studies may suggest a trend of these DEB and as an additional goodness, to acknowledge if the strategies carried out by health services are impacting positively over time in population. Therefore it is suggested for future investigations to consider perform longitudinal studies even the enormous time and costs that this design requires, coinciding with Jacobi, Hayward, et al. (2004) who mention that the first step in identifying risk factors should be through longitudinal studies.

The last methodological confounding factor in this review has to do with instruments, highlighting two aspects: (a) type of question and (b) answer option. The first point arises when were analyzed the different questions utilized to estimate the point prevalence of DEB. In this analysis were identified questions such as “Do you currently diet/binge/vomit twice a week…?”, “during the past six months or in the past 1 year do you…?” and “have you ever…?”, in which was observed temporal differences thus different types of prevalence. For instance two studies carried out in the same country with similar sample sizes and similar participants’ features, found prevalence rates extremely discrepant. Huon et al. (2002) assessed the prevalence rate of restrictive dieting through questions that refer to the current moment finding 0.6%, while Tam et al. (2007) evaluated the same behavior with questions that enquired participants to think in the past year, yielding 51.7% suggesting that the temporality expressed implicitly in questions have a significant influence in the prevalence rates. Moreover it is common to use screening instruments to assess prevalence rates; however it is not enough to count with a wide recognized instrument, it is necessary to carefully select items that reflect the presence of the behavior and not the attitude toward the behavior. For example, it is better to select items such as “I vomit after eating” instead of “I would like to vomit after eating”.

The second point to discuss concerning instruments is the use of Likert scales to identify the DEB, since criteria were not specified to consider presence or absence of the behaviors, which is crucial factor in epidemiological research. For example, in a Likert scale with five answer options (always, usually, sometimes, rarely and never), rigorous criteria may limit presence as “always” and absence as “never”, but less exigent criteria may consider more than one answer option. This aspect was undervalued since almost any study specified meticulously how the presence or absence of DEB was established.

Data collection is one of the methodological procedures more important in any research, because this stage allows responding research questions proposed (Singh, 2006), therefore, the selection of the instrument must be a decision carefully taken since this incises in the results of research. To this respect, paper-and-pencil instruments are useful tools in epidemiological research to collect large amounts of information at a low cost per respondent, notwithstanding the instrument selected need to cover two important conditions: validity and reliability in specific populations (Bhattacherjee, 2012).

According to the results of this review restrictive dieting and binge eating were within the more prevalent DEB, supporting the last hypothesis formulated for this review. This finding could be influenced by the last confounding factor that has to do with cultural issues. To illustrate this, we can observe that Westenhoefer (2001) in a longitudinal study found a decrease in most of DEB, one possible explanation that he proposes is that Germany is considered a country where people is more aware about health and wellness issues; supporting this proposal, the International Markets Bureau (2010) mention that experts and media have worked together to warn population about health risks caused by the practice of DEB, making the wellbeing as a lifestyle and marketing concept. In contrast, Nunes et al. (2003) reported one of the highest prevalence rates in laxatives (8.5%) in Brazilian population, according to the authors this may be due to Brazilians women have more access to diet pills than women in other countries, these pills are each time more accessible to adolescents since medical prescription is no needed to obtain them, and the fact that media promotes them as “soft or natural weight control methods” increase the desire to consume these products. Besides, Brazil is considered one of the countries with the highest beauty standards, hence one of the countries where more cosmetic surgeries are performed per year in the world (International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 2013) this may cause a strong social pressure in women, pushing them to consume products that will help them to reach “the perfect body”. Other study that reflects cultural aspects in prevalence rates is the one carried out by Kiziltan et al. (2006) in Turkish population; they reported high prevalence rates in fasting (10%) and binge eating (16%). One possible explanation is that fasting is a behavior performed by Muslims girls for religious reasons; it is known that long periods without eating may lead an increased amount of food intake and this may be misunderstood as a binge eating, yielding high prevalence rates (Peláez et al., 2005). This underlines the importance to adapt culturally the instruments to detect when the practice of DEB is truly pathological and not performed for religious, cultural or health purposes.

The analysis carried out in this literature review add knowledge to understand the differences among studies about prevalence rates of DEB, however some limitations should be consider: (1) male prevalence rates were not analyzed, it is suggested that future research address this aspect since there is evidence that the practice of these behaviors are becoming more popular among adolescent boys and young men (Fortes et al., 2013; Petrie et al., 2008), (2) the search review was performed only in two data bases (MEDLINE and SCIENCE DIRECT), it is suggested that further research included information from other sources such as books, dissertations, articles in different languages or indexed in different data bases to enrich the knowledge in epidemiological field of ED, (3) excessive exercise is also a relevant DEB but was not included in this review, so further research should study it since there is evidence that it is associated with muscle dysmorphia (Hale et al., 2013) and (4) although this study was design as a systematic review it is possible to also consider it as a first approximation of a meta-analysis, since according with Crombie and Davies (2005) the validity of a meta-analysis depends on the quality of the systematic review on which it is based, therefore it is suggested that future researches give continuity to this work to provide more detailed and accurate information on DEB, following criteria proposed by PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses; Moher et al., 2009).

The main strength of this paper is the meticulous analysis performed in each article; this allowed deriving the following methodological considerations for epidemiological research in ED, which will contribute to describe more accurately the real state of the population study, as well as to have a greater scientific rigor:

- (1)

Sample. It is suggested for future studies to take into account the representativeness of the population preferably through randomized methods, if it is not possible to achieve this criteria, Jacobi, Hayward, et al. (2004) recommend a community sample size at least of 3000 participants, which may or may not be selected randomly. Also it is important to have a good response rate; it is suggested to follow the criteria proposed by Punch (2003).

- (2)

Research design. If the aim of research is to know the point prevalence of DEB and ED, it is suggested to use a cross-sectional design. However if the purpose of the study is to determine if prevalence rates have rise, decrease or remain stable over time, longitudinal design is the most suitable to clarify this constant discussion in specialized literature.

- (3)

Instruments. There are instruments developed specifically to assess DEB with epidemiological aims (Ferreira & Veiga, 2008; Hay, 1998; Unikel, Bojorquez, & Carreño, 2004). According to this review, the EAT was the most widely used instrument to assess the prevalence of DEB, however this instrument was created to measure attitudes and behaviors common among ED, not for epidemiological purposes. Independently of the instruments utilized it is necessary to consider three crucial points: (1) The instruction should encourage the participant to answer thinking in the past three months, given the frequency proposed by DSM-5; (2) If the answer options of the instrument have a Likert scale is imperative that the authors explain which answer option(s) was/were chosen for “presence” and which for “absence” of DEB; and (3) Frequency parameters are determinant in ED, these should be reflected also in epidemiological data; for instance to engage in vomiting an average of 1–3 times per week during the past three months is enough to consider it as an indicator of presence of this DEB, therefore it is necessary to specify what does it mean “rarely, sometimes, often, usually, always” since each participant may attribute different frequency to each answer option and at the same time we can prevent the overestimation of prevalence rates. If the Likert scale goes from “never” to “always” it is suggested to consider the following frequency for each answer option: never=absence; rarely=once a month or less; sometimes=two or more times a month; often=once a week; usually=two-six times a week; always=once a day or more.

This research was sponsored by CONACyT No. 131865-H granted to Dr. Juan Manuel Mancilla-Díaz. The first author was supported by a doctoral scholarship from CONACyT Scholar No. 245864.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

References marked with an asterisk indicate the articles considered in the analysis.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.