Transmigration is a rare and special phenomenon in that intraosseous tooth migration takes place, through the midsymphyseal or mid palatine suture. Transmigration typically affects the mandibular canines. These teeth usually remain impacted and asymptomatic but in some cases they ectopically erupt in the midline or next to the contralateral side. Transmigrated teeth can cause neurologic symptoms and pressure resorption of the adjacent teeth roots. A 15-year-old girl was referred to our clinic complaining of pain in the inferior incisives. On intraoral examination, right mandibular deciduous canine was seen to be retained. Panoramic radiograph revealed a horizontally impacted right mandibular permanent canine migrated toward the midline and located below the apices of the incisives. The tooth was surgically removed under general anesthesia. The presence of an overretained mandibular deciduous canine should always be investigated radiographically.

A transmigração é um fenómeno raro no qual dentes não erupcionados migram através da linha média maxilar ou mandibular. A transmigração, geralmente, afeta os caninos mandibulares. Normalmente estes dentes permanecem impactados e assintomáticos mas em alguns casos podem erupcionar na linha média ou na região do canino contralateral. Os dentes transmigrados podem originar sintomas tais como dor ou reabsorção das raízes dos dentes adjacentes. Uma menina de 15 anos de idade compareceu a nossa consulta referindo dor nos incisivos inferiores. Ao exame clínico foi possível verificar a presença na arcada do canino mandibular direito decíduo. A radiografia panorâmica revelou que o canino permanente mandibular direito se encontrava impactado numa posição horizontal abaixo dos ápices dos incisivos tendo migrado em direção ao lado contralateral, ultrapassando a linha média. O dente foi removido cirurgicamente, sob o efeito de anestesia geral. A presença na arcada de um canino mandibular decíduo deve ser considerada suspeita, justificando investigação radiográfica.

Transmigration is a rare phenomenon in which non-erupted teeth migrate across the midline. It is more common in women than in men in a 1.6:1 ratio,1 the mandibular left side being more often affected than the right side.2 Transmigration of permanent mandibular canines is an unusual phenomenon with a prevalence reported between 0.14 and 0.31%.3–5 The etiology remains to date poorly understood. However, hereditary, mandibular trauma at a very early age or a small obstacle such as a root fragment or the presence of a cyst could be sufficient to divert such a tooth to an abnormal path.6 Transmigration of mandibular canines ranges from mild to extreme. Mupparapu7 classified transmigrated mandibular canines into five types based on their migratory patterns and their positions in the jaw: type I, canine impacted mesioangularly across the midline, labial or lingual to the anterior teeth; type II, canine horizontally impacted near the inferior border of the mandible inferior to the apices of the incisors; type III, canine erupting on the contralateral side; type IV, canine horizontally impacted near the inferior border of the mandible below the apices of the posterior teeth on the opposite side; type V, canine positioned vertically in the midline with the long axis of the tooth crossing the midline. Usually there are no clinical symptoms, although the formation of follicular cysts, chronic infection as well as pain in the lower incisors have been reported.8 The absence of permanent mandibular canine beyond the average chronological age of eruption makes taking a panoramic radiograph for screening imperative. In most cases periapical radiographs are not sufficient to detect transmigrated canines9 which typically remain impacted10–16 but in some cases they may erupt ectopically at the midline17 or on the opposite side of the arch.18–21 Surgical removal, transplantation, radiographic follow-up and surgical exposure with orthodontic treatment are suggested as treatment options for transmigrated canines.22 In some patients when indications for removal do not exist, it is acceptable to leave the impacted canine in situ. In such cases periodic radiographic follow-up is essential to check for any pathologic change.23

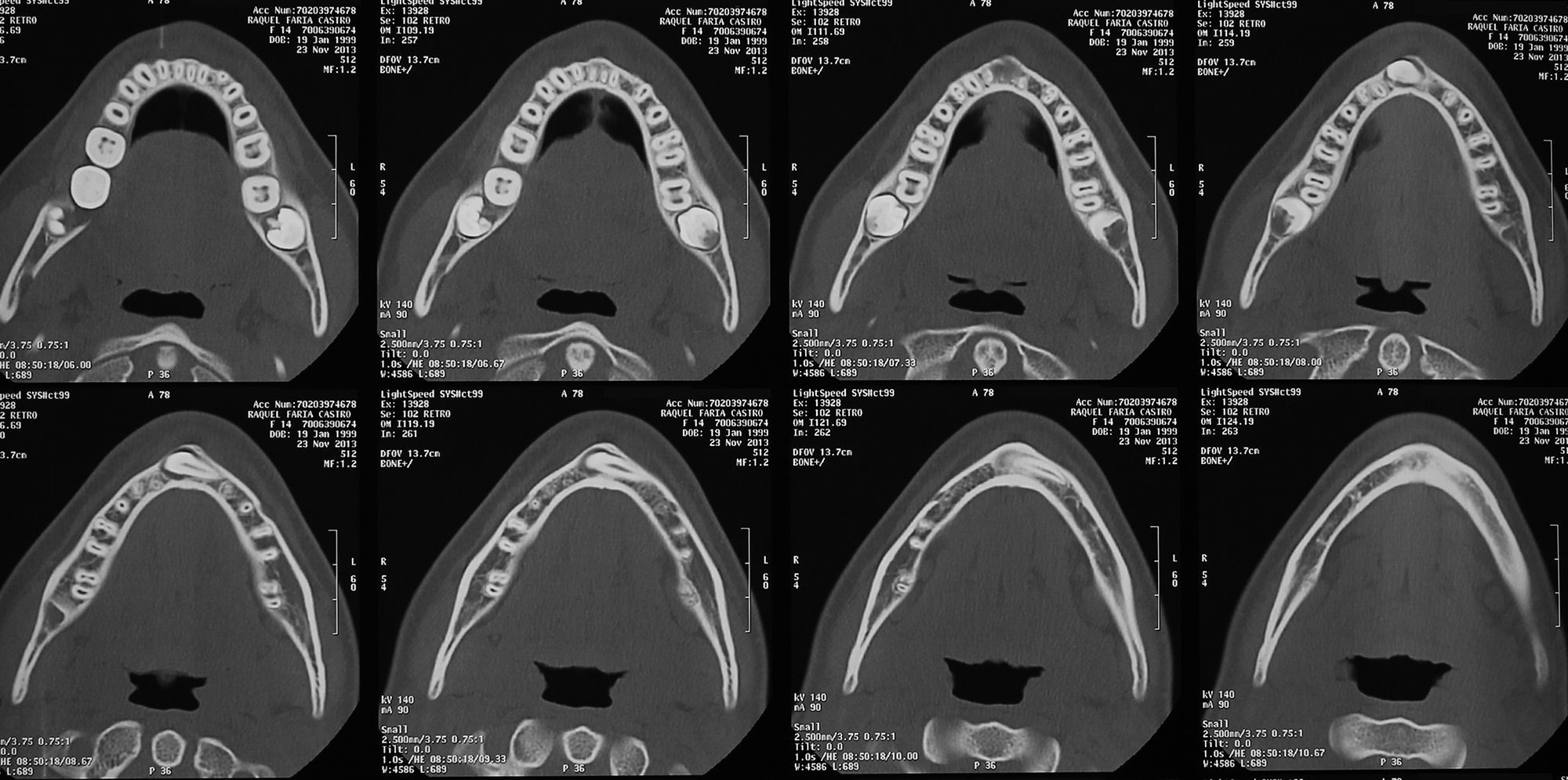

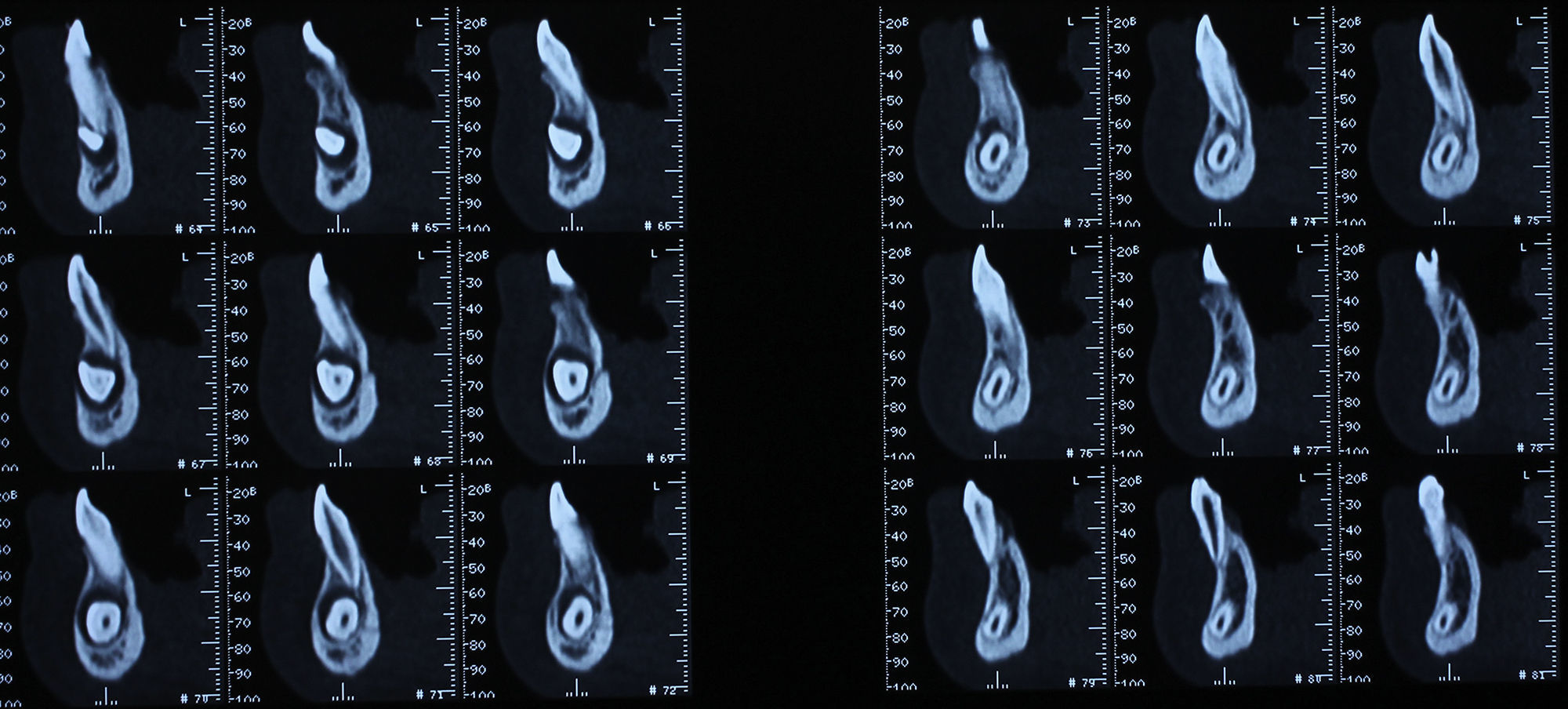

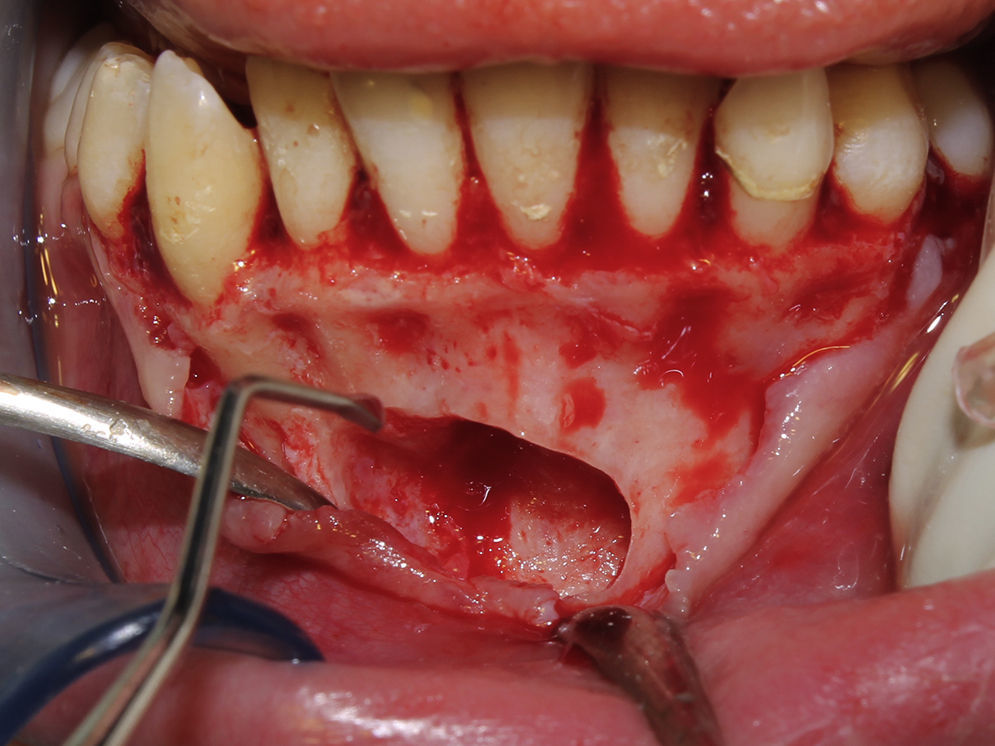

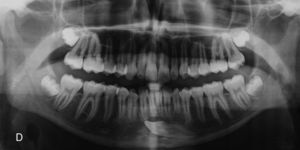

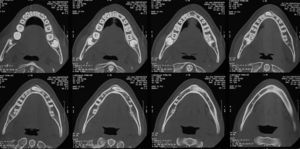

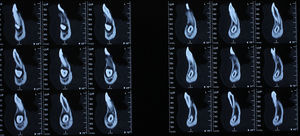

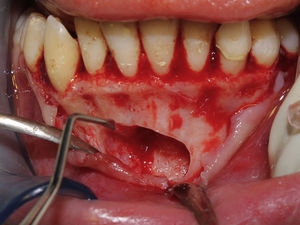

Case reportA 15-year-old female patient attended our Dental Medicine appointment complaining of sensitivity and pain in mandibular incisors. Sensitivity and pain were reported for the past two months. The clinical history did not reveal any relevant information and there was no previous history of trauma. On clinical examination the lower incisors show no significant abnormality. Right mandibular deciduous canine was present in the mandibular arch (Fig. 1). A vitality test was performed and all four teeth were found to be vital. As a part of the routine assessment a panoramic radiograph was taken, which revealed the presence of an impacted transmigrated canine in a horizontal position below the root apices of lower incisors (Fig. 2). Due to the lack of any other clinical evidence directing us toward the cause of pain we accepted the impacted mandibular canine as a potential cause. The patient was asked to take a computerized axial tomography to program surgical extraction of the tooth (Figs. 3 and 4) which occurred under general anesthesia. A buccal mucoperiosteal flap was raised and the tooth was exposed after removing the cortical plate (Figs. 5–7).

We reserved the option of intentional root canal treatment of incisors if the symptoms did not subside. The patient was on periodic control review. She remained free of symptoms and did not require further intervention. Adequate healing of the bone could be seen in a panoramic radiograph taken 1 year after surgery (Fig. 8).

DiscussionAndo et al.24 were the first to use the term “transmigration”. Tarsiano et al.25 defined transmigration as the phenomenon of an unerupted mandibular canine crossing the midline. Javid11 expanded the definition to include the cases in which more than half of the tooth had passed through the midline. Joshi9 and Auluck et al.26 suggested that the tendency of a canine to cross the midline suture is a more important consideration than the actual distance of migration after crossing the midline. Moreover, the stage of transmigration of the tooth at the time of examination is a determining factor in the distance travelled.

Canine impaction is more prevalent in the maxilla than in the mandible,5 but transmigration of maxillary canines is rare maybe because the maxillary midpalatal suture acts as a barrier preventing transmigration to the contralateral side. Maxillary canine transmigration might be difficult also because of anatomic constraints, which include the relatively short distance between the floor of the nasal fossa and the roots of maxillary incisors.5,27,28 The mandibular canine is the only tooth in which migration and crossing of the midline have been documented.7,27–29

From the data published, it is possible to define various behavior patterns of transmigrated mandibular canines. In particular, Mupparapu described five patterns. Most of the cases reported in the literature would fit into type I7; however, according to this classification, our case was a type II transmigrated canine.

Bilateral transmigration is extremely rare and there are very few published cases.27,30

Treatment considerations for transmigrated teeth depend on the stage of development, distance of migration, angulation when they are identified and whether the patient is symptomatic or not. Treatment options proposed for transmigrated mandibular canines are surgical removal, auto-transplantation and surgical exposure with orthodontic alignment. Surgical extraction is the most preferred treatment, especially if the patient is symptomatic or has any associated abnormalities7 being more favorable than trying to bring the tooth back to its original place, especially when the mandibular arch is crowded and requires therapeutic extractions to correct the incisor crowding. However, if the other teeth are in a normal position and space for the transmigrated canine is sufficient, a transplantation process may be undertaken. Due to unfavorable position of the transmigrated canine, orthodontic repositioning is difficult. Until now, successful corrections of transmigrated canines using orthodontic treatment have rarely been documented in the literature.31,32 Wertz32 advocated that if the tip of the crown has migrated past the adjacent lateral incisor root apex, it might be mechanically impossible to bring the aberrant canine into its normal place. In our case we opted for surgical removal of transmigrated canine due to the fact that patient was symptomatic and due to an unfavorable position of the impacted tooth to undergo orthodontic traction.

If the patient is asymptomatic, the transmigrated canine could be left in place, but it is very important to control movement of these teeth by taking regular radiographs.8,20

The deciduous canine remains overretained most of the time in such cases. Its root does show resorption but is rather slow, so it could be left in site.22 Due to our patient's age and root resorption's degree we decided to leave the deciduous canine. In the future the deciduous tooth can be replaced by an intraosseous implant. An orthodontic study should be done previously to calculate the need for realigning the inferior incisors and open space for implant placement. In the panoramic radiograph some root reabsorption seems to exist in the mandibular right canine and lateral incisor. The patient is in periodic review to control the vitality of those teeth.

Transmigrated canine maintains its nerve supply from the original site.9 This is an important factor when surgical removal is planned under local anesthesia, because it is necessary to anesthetize the nerve of the side to which the canine belongs. However, like it happened in our case, if general anesthesia is to be used, this problem does not arise.

ConclusionThe presence of an overretained mandibular deciduous canine should always be investigated radiologically. An intraoral radiograph usually is not sufficient, and it should be supplemented preferably by an orthopantomograph. Early diagnosis with timely orthodontic or surgical intervention can help dentists preserve canines, which play an important role, in both esthetics and function in the human dentition.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.