Multiple education organizations and experts, including the recent education law in Spain, emphasize the significance of nurturing emotional skills from childhood to prevent the development of emotional and behavioral disorders. One of these skills is emotion knowledge (EK), which is closely linked to personal and social adjustment from early years, and later psychosocial adaptation. The present study aims to provide an assessment tool for EK in the bilingual context of the Basque Country and to provide evidence about the relationship between EK and various behavioral outcomes in early childhood education. The research involved 455 children between 3 and 6 years of old. The Emotion Matching Task, which measures the EK, was adapted to the bilingual context of the Basque Country has shown good psychometric properties and appropriate factor fit. The study also revealed the factor invariance of the Spanish and Basque versions, as well as invariance by sex. The results demonstrated that girls have higher EK than boys. Additionally, EK was associated with fewer externalizing, internalizing, and attention problems, as well as with lower atypicality and withdrawal, while higher EK was linked to greater adaptive skills. These findings support the need for interventions focused on the development of emotional skills and the suitable tools to assess their effectiveness.

Numerosos organismos y especialistas en educación, incluyendo la reciente ley de educación en España, destacan la importancia de favorecer el desarrollo de las habilidades emocionales desde la infancia y así prevenir la aparición de problemas emocionales y conductuales. Entre estas habilidades se encuentra el conocimiento emocional (CE), vinculado con el ajuste personal y social desde los primeros años, y con la posterior adaptación psicosocial. El presente estudio pretende ofrecer una herramienta para evaluar el CE en el contexto bilingüe del País Vasco y aportar evidencias de la relación entre el CE y diversos indicadores conductuales en Educación Infantil. Han participado 455 niños y niñas entre 3 y 6 años. Inicialmente se ha adaptado el Emotion Matching Task, que evalúa el CE, en el contexto bilingüe del País Vasco, que ha mostrado buenas propiedades psicométricas y un adecuado ajuste factorial. Además, se ha evidenciado la invarianza factorial de las versiones en español y en euskera, así como en función del sexo. Los resultados han mostrado que las niñas tienen superior CE, así como que el CE está asociado con menos problemas externalizantes, internalizantes y de atención, y con menor atipicidad y retraimiento. Finalmente, un superior CE se ha relacionado con mayores habilidades adaptativas. Estos resultados avalan la necesidad de contar con intervenciones dirigidas al desarrollo de habilidades emocionales, y de disponer de herramientas adecuadas para evaluar sus resultados.

Many studies have confirmed the importance of emotional skills in children’s psychosocial adjustment (Domitrovich et al., 2017; LoBue et al., 2019). Even during the earliest years of their lives, children recognize and imitate facial expressions and develop the ability to attach meaning to them (Denham, 1998; Ruba & Pollak, 2020; Zeidner et al., 2003). This set of intrinsically human capacities (Izard et al., 2011) become the cornerstone of emotional competence when they develop into skills, with competence being understood as the effective use of skills in situations of emotional activation (Buckley & Saarni, 2013; Campos et al., 2018).

One example of this is emotion knowledge (EK), defined as a set of skills that enable an individual to perceive emotional signals and label and understand emotions (Izard et al., 2011). From childhood onwards, EK promotes social adaptation, good mental health and school success (Domitrovich et al., 2017; Lafay et al., 2023; MacCann et al., 2020; OECD, 2015, 2021; Schoeps et al., 2021; Trentacosta et al., 2022; Voltmer & von Salisch, 2017), whereas its absence has been linked to the emergence of social and behavioral problems (Domitrovich et al., 2017; Ekerim-Akbulut et al., 2020; Izard et al., 2001). The development of EK begins with emotion perception, before moving on to labeling and, finally, understanding (Denham, 2019; Woodard et al., 2022). EK is also vital to the development of emotion regulation (Conte et al., 2019; Di Maggio et al., 2016).

The gradual acquisition of EK skills is based on general maturation and linguistic development (Conte et al., 2019; Denham, 2019; Hoemann et al., 2019) and is fostered by increased exposure to emotional experiences during social interactions. A more mature receptive vocabulary fosters the use of emotional language, which in turn facilities children’s learning and understanding of the messages present in their environment, laying the groundwork for emotional understanding (Harden et al., 2014; Nook et al., 2020; Sarmento-Henrique et al., 2020; Zeidner et al., 2003). In relation to sex, the extant literature is less consistent, and although most studies report higher EK levels among girls (Alwaely et al., 2021; Bennett et al., 2005; McClure, 2000; Voltmer & von Salisch, 2017), some fail to find any such differences (Conte et al., 2019; Fidalgo et al., 2018).

EK not only affects personal, social and school adjustment during early childhood, it also has a major impact during subsequent life stages, fostering adaptation during middle and late childhood and adolescence. Children with higher levels of EK have fewer internalizing, externalizing and attention problems, as well as lower levels of withdrawal (Alonso-Alberca et al., 2012; Domitrovich et al., 2017; Ekerim-Akbulut et al., 2020; Izard et al., 2001; O’Toole et al., 2013; Trentacosta & Fine, 2010; Zhang et al., 2024). A positive association has been observed also between EK and general school adjustment and academic performance, during both childhood (Domitrovich et al., 2017; Izard et al., 2001; MacCann et al., 2020; Voltmer & von Salisch, 2017) and later life stages (Denham et al., 2014).

In light of these results, and with the aim of fostering emotional competence, over recent years many different interventions have been developed to help children develop their emotional skills (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Housman et al., 2023; Lafay et al., 2023) and many studies have been conducted to assess their benefits (Murano et al., 2020). Both individual researchers (Eisenberg, 2020; LoBue et al., 2019) and international organizations (OECD, 2015) have highlighted the importance of early intervention in order to strengthen the protective effects of emotional skills and prevent problems associated with their absence. However, measurement instruments especially designed for use with children are required to obtain valid and reliable information about the impact of these interventions and respondents’ ability to identify emotions, process the information obtained and regulate their feelings.

Growing scientific interest in emotional competence during childhood has resulted in a large number of studies focused on measuring this construct (Denham, Bassett et al., 2020; Fernald et al., 2017; Kamboukos et al., 2022). Many authors argue that instruments designed for this purpose must comply with certain validity and reliability criteria, and be sensitive enough to detect different levels of emotional skill acquisition (Alonso-Alberca & Vergara, 2018; Denham, Ferrier et al., 2020; Wigelsworth et al., 2010), since only in this way will they help increase existing knowledge of the variables that affect the development of emotional skills and the impact that these skills have on diverse psychosocial factors.

Emotional skills in Spanish education lawThe Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) claims that, among other things, emotional skills are essential to people’s wellbeing and the advancement of society (OECD, 2015), highlighting the crucial role played by early schooling in the acquisition of these skills. In Spain, emotional competence has only recently been included in the school curriculum (Organic Law 3/2020), although the text of the new law underscores the importance of affective development during the preschool years as the basis for future learning and the establishment of children’s personality. It also highlights the importance of developing assessment strategies and objective indicators for measuring the acquisition of emotional skills and detecting areas requiring intervention. In Spain, however, there are few validated instruments for measuring these skills, particularly during the preschool years (Alonso-Alberca & Vergara, 2018; Arrivillaga & Extremera, 2020).

Assessment of bilingual contextsAccording to the guidelines published by the International Test Comission (2017), bilingual contexts require specially adapted instruments that enable assessments to be carried out in each individual's preferred language and guarantee the semantic, linguistic and cultural equivalence of the elements measured. Adapting assessment instruments to bilingual contexts is particularly important during early childhood, a period in which one language of reference is usually dominant. In Europe, several counties have two or more co-official languages, including Belgium, Switzerland, Spain, Italy and the United Kingdom. In Spain, for example, although Castilian Spanish is the most widely-spoken language, Catalonian, Valencian, Basque and Galician are spoken also in some autonomous communities. As a result of this situation, tens of millions of people need to be assessed in their preferred language. In the Basque Country, which has a population of two million, Basque and Spanish are co-official languages. According to recent data, 36.2% of the population of the Basque Country speak Basque as their first language, with this figure being even higher among younger generations (Basque Government, Department of Culture and Language Policy, 2023).

In the field of emotions, research carried out in bilingual contexts suggests that early experience with languages determines an individual's linguistic preference for communicating their feelings (Dewaele, 2012), mainly due to the specificities of the associated emotional vocabulary (Jackson et al., 2019; Lindquist, 2021; Lobue & Ogren, 2022). In this respect, the review carried out by Pavlenko (2012) concludes that, in bilingual contexts, the dominant language has an advantage in terms of both emotional processing and electrodermal reactivity, suggesting that a language learned later in life may be processed semantically, but not affectively. This means that, in order to properly assess emotional skills during childhood and capture all possible nuances, it is vital to have valid, reliable measures that are adapted to the different linguistic and cultural contexts in which they are to be applied.

Emotion matching taskThe Emotion Matching Task (EMT), developed by Carroll Izard (Morgan et al., 2010), is an instrument designed to assess EK among preschool children. Children are shown photographs of other boys and girls expressing basic emotions (happiness, sadness, anger and fear) and are asked to associate different emotional expressions (matching), establish links between emotional expressions and different situations (understanding), name emotional expressions (labeling) and, finally, point to the expression that corresponds to a stated emotion (identification or recognition).

The EMT is administered individually and is a self-report instrument. It is simple to complete and score and has minimal verbal requirements, thereby complying with the requisites established for measuring emotional skills among preschoolers (Alonso-Alberca & Vergara, 2018; Denham, Ferrier et al., 2020; Trentacosta & Fine, 2010). The EMT was originally developed for use in the USA (Morgan et al., 2010), but has since been validated in Spain (Alonso-Alberca et al., 2012), Italy (Di Maggio et al., 2013), Brazil (Andrade et al., 2014), Sudan (Alwaely et al., 2021) and Croatia (Babić Čikeš et al., 2023), with studies demonstrating its ability to identify associations between EK and emotion regulation, effortful control and behavioral and emotional problems (Alonso-Alberca et al., 2020; Belmonte-Darraz et al., 2021; Brock et al., 2019; Heinze et al., 2015; Morgan et al., 2010). Moreover, the EMT has been found to be sensitive enough to detect changes in EK following interventions aimed at improving this set of skills (Di Maggio et al., 2016; Dow, 2016; Finlon et al., 2015; Izard et al., 2004; Kats Gold et al., 2020).

The present studyThe general aim of the present study is to adapt and validate an EK assessment instrument in the Basque Country. The specific aims are: first, to adapt the EMT to the Basque language and to analyze factor structure and invariance between the Spanish and Basque versions; second, to analyze the invariance of the instrument in accordance with sex, in order to rule out any possibility of sex-based bias; third, to study the predictive capacity of age, sex and receptive vocabulary for EK; and fourth, to analyze the influence of EK on different behavioral dimensions, including adaptive skills, externalizing, internalizing and attention problems, atypicity and withdrawal, with the twofold aim of providing evidence of both criterion validity and the association between EK and behavior.

In terms of hypotheses, first, we expected to confirm the factor structure proposed by the original authors of the instrument and to demonstrate invariance between the two language versions. Second, we also expected to confirm the invariance of the instrument in terms of sex. Third, we expected age and receptive vocabulary to positively predict EK; and we expected girls to outperform boys. Finally, we expected higher levels of EK to be associated with better adaptive skills and fewer behavioral problems.

MethodParticipantsParticipants were 455 children (48.4% girls) aged between 35 and 75 months (M = 55.8 and SD = 10.4). The age distribution of the sample was as follows: 26.6% were aged 3 years, 33% were aged 4 years and 40.4% were aged 5 years. The distribution by sex in each age group (see Supplementary material 1, https://acortar.link/vXh19o) was balanced for both the Spanish χ2 (2) = 0.18, p = .91 and the Basque-speaking samples χ2 (2) = 0.14, p = .93. We used a heterogeneous convenience sampling technique that included children from Madrid (Spanish-speakers) and Gipuzkoa (Basque-speakers). The Spanish-speaking sample comprised 250 children (Mage = 53.8 months, SD = 10.3), and the Basque-speaking sample 205 children (Mage = 58.11 months, SD = 9.94).

InstrumentsEmotion Matching Task (EMT; Morgan et al., 2010). This instrument measures EK through four tasks, each with 12 items. It comprises 182 photographs of children whose facial expressions denote happiness, sadness, anger or fear. The tasks require respondents to associate emotional expressions, identify the cause of emotions, label emotions and recognize emotions. Each response is scored as either 0 = incorrect or 1 = correct. The original instrument has been found to have good internal consistency (α = .88), with evidence of both convergent and criterion validity. The Spanish version (Alonso-Alberca et al., 2012) has also been found to have adequate psychometric properties, with high internal consistency (Ω = .82).

Peabody (PPVT-III; Dunn et al., 2006). This instrument assesses receptive vocabulary and is often used as a control measure of children's verbal skills. Participants are shown a card containing four pictures and are asked to select the one that best represents the meaning of a spoken word. The Spanish version has been found to have adequate internal consistency (α = .91) and correlates with verbal ability and general intelligence measures. In the present study we used a Basque language version developed by the authors with the permission of the publishers.

Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC Spanish version; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). The BASC evaluates adaptive and maladaptive dimensions of children’s behavior. In the present study we used the T1 questionnaire, which is completed by teachers. This questionnaire has 106 items grouped into externalizing problems, internalizing problems, adaptive skills, withdrawal, atypicality and attention problems. The scale has good internal consistency.

ProcedureThe study was approved by the University of the Basque Country’s Ethics Committee. The Spanish-speaking sample completed the validated Spanish version of the EMT. The Basque language version was developed using a double back translation process. Two experts with experience working with emotional content translated the instrument from English to Basque and then compared their results to reach a consensus for each item. Next, another two experts translated the instrument back from Basque into English. Differences in meaning were then analyzed and the pertinent adjustments made. After conducting a pilot test and making the necessary modifications, the definitive version was drafted. Throughout the 2017–2018 academic year, we contacted schools to invite them to participate, and the data were collected during the 2018–2019 academic year. The management teams of participating schools gave their consent prior to the start of the study, as did all participating tutors and the parents of participating children. Each child was also asked to give their verbal consent before completing the tasks. Three educational psychologists collected the data during individual sessions lasting between 15 and 25 minutes, administering the PPVT first, followed by the EMT. Prior to these sessions, the psychologists visited each class group to introduce themselves and foster familiarity and trust. Finally, the children’s teachers completed the BASC questionnaire on their behavior.

Design and data analysisA cross-sectional survey design was used. Descriptive analyses were carried out to verify similarity in the distribution of the variables sex, age and receptive vocabulary across the two samples. Differences between the samples in the behavioral dimensions of the BASC were also analyzed. Due to the categorical nature of the items and the lack of normal distribution, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to explore the factor structure of the EMT, using the WLSMV (weighted least square mean and variance adjusted) estimator. The following goodness of fit criteria were established: CFI (comparative fit index), TLI (Tucker–Lewis index) ≥ .90, and RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) ≤ .05), and the models were compared using the likelihood ratio (Δχ2) and increase in CFI (≤ .01). To measure the reliability of the scale, we calculated Cronbach’s Alpha, McDonald’s Omega, Composite Reliability and Average Variance Extracted. The invariance of the measure across language and sex was assessed by means of a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis. The configural and scalar models were analyzed, comparing the Spanish and Basque language versions and the male and female samples. Finally, we used a structural equations model to analyze the influence of age, sex and receptive vocabulary on EK, as well as the impact of EK on behavioral dimensions. All data analyses were carried out using the Mplus 7.31 and SPSS 28.0.0.1(14) statistical software packages.

ResultsThe descriptive analyses carried out returned similar values in both samples for all variables under study (see Supplementary material 2, https://acortar.link/vXh19o).

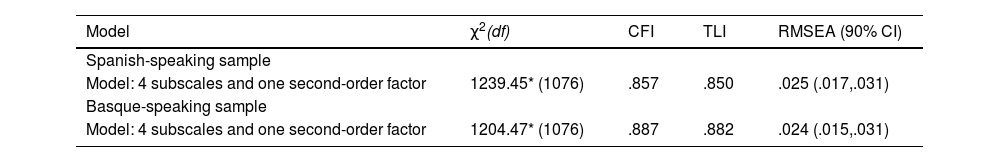

Analysis of the factor structure and dimensions of the EMTWe analyzed the goodness of fit of the four-dimensional model of the EMT proposed by the original authors, plus a second-order global EK factor, using both versions of the instrument, finding an adequate fit in both samples (Table 1).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of both language versions

| Model | χ2(df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish-speaking sample | ||||

| Model: 4 subscales and one second-order factor | 1239.45* (1076) | .857 | .850 | .025 (.017,.031) |

| Basque-speaking sample | ||||

| Model: 4 subscales and one second-order factor | 1204.47* (1076) | .887 | .882 | .024 (.015,.031) |

Note. χ2 = chi-squared; df = degrees of freedom; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval.

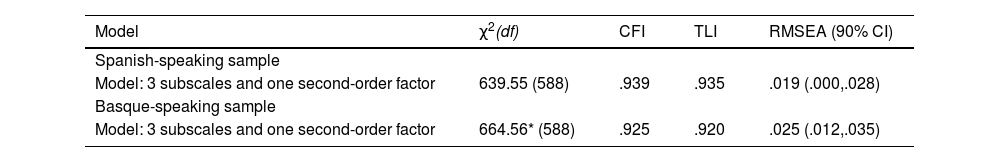

A ceiling effect was observed in the EMT4 subscale in relation to the univariate proportions of the items, which may explain the poor fit found in the confirmatory factor analysis. The decision was therefore made to eliminate this dimension and to analyze a three-dimensional model with a second-order global EK factor. A strong correlation was observed between some items of the EMT3 subscale, particularly between items 4 and 7, as well as between item 8 and items 10 and 11, which were included in the model. The results obtained are presented in Table 2.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of both language versions after eliminating subscale 4

| Model | χ2(df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish-speaking sample | ||||

| Model: 3 subscales and one second-order factor | 639.55 (588) | .939 | .935 | .019 (.000,.028) |

| Basque-speaking sample | ||||

| Model: 3 subscales and one second-order factor | 664.56* (588) | .925 | .920 | .025 (.012,.035) |

Note. χ2 = chi-squared; df = degrees of freedom; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval.

The three-factor model with one second-order global factor was found to have a good fit in both samples. In this study, the reliability values for the Spanish and Basque-speaking language versions of the EMT were Cronbach’s Alpha: .78 and .82; McDonald’s Omega: .81 and .83; Composite Reliability: .90 and .93; and Average Variance Extracted: .24 and .30, respectively.

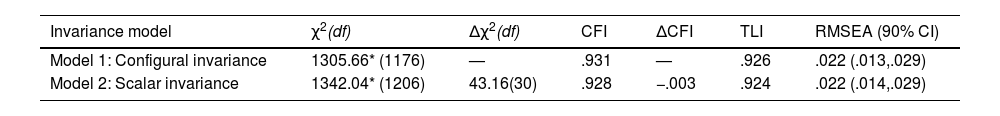

EMT invariance across language and sexWe analyzed the invariance of the measure across the different language versions. To do this, we first analyzed the three-dimensional model without the second-order factor (Table 3).

Factor invariance in accordance with language

| Invariance model | χ2(df) | Δχ2(df) | CFI | ΔCFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Configural invariance | 1305.66* (1176) | — | .931 | — | .926 | .022 (.013,.029) |

| Model 2: Scalar invariance | 1342.04* (1206) | 43.16(30) | .928 | −.003 | .924 | .022 (.014,.029) |

Note. χ2 = chi-squared; df = degrees of freedom; Δχ2 = change in chi-squared; CFI = comparative fit index; ΔCFI = change in CFI; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval.

According to the results obtained (Table 3), the EMT displays scalar invariance in accordance with language, since the increase in chi-squared was not statistically significant and the increase in CFI was less than .01. Next, we confirmed scalar invariance when the second-order factor was included, with the results indicating adequate fit: χ2 (1210) = 1344.55, CFI = .928, TLI = .926, RMSEA (90% CI) = .022 (.013, .029). Most of the standardized weights of the items in the subscales of both language versions of the instrument were statistically significant with values of over .25 (see Supplementary material 3, https://acortar.link/vXh19o), and even though three items had lower weights, given the adequate fit of the model, we opted not to eliminate them so as to maintain the original version of the instrument and facilitate future cross-cultural comparisons. Next, to confirm the absence of sex bias, we analyzed invariance in accordance with this variable, using a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (Table 4).

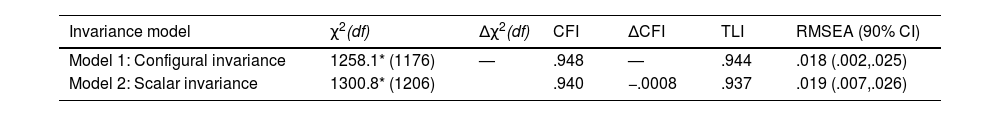

Factor invariance by sex

| Invariance model | χ2(df) | Δχ2(df) | CFI | ΔCFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Configural invariance | 1258.1* (1176) | — | .948 | — | .944 | .018 (.002,.025) |

| Model 2: Scalar invariance | 1300.8* (1206) | .940 | −.0008 | .937 | .019 (.007,.026) |

Note. χ2 = chi-squared; df = degrees of freedom; Δχ2 = change in chi-squared; CFI = comparative fit index; ΔCFI = change in CFI; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval.

The results indicated a good fit. Although a statistically significant increase was observed in χ2, the increase in CFI was less than .01, indicating no difference between the two models (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). The results therefore confirmed scalar invariance and ruled out the possibility of sex bias in the two language versions of the instrument used in this study. Finally, the analysis of scalar invariance when the second-order factor was included indicated an adequate fit: χ2 (1210) = 1301.77, CFI = .942, TLI = .939, RMSEA (90% CI) = .018 (.006, .026).

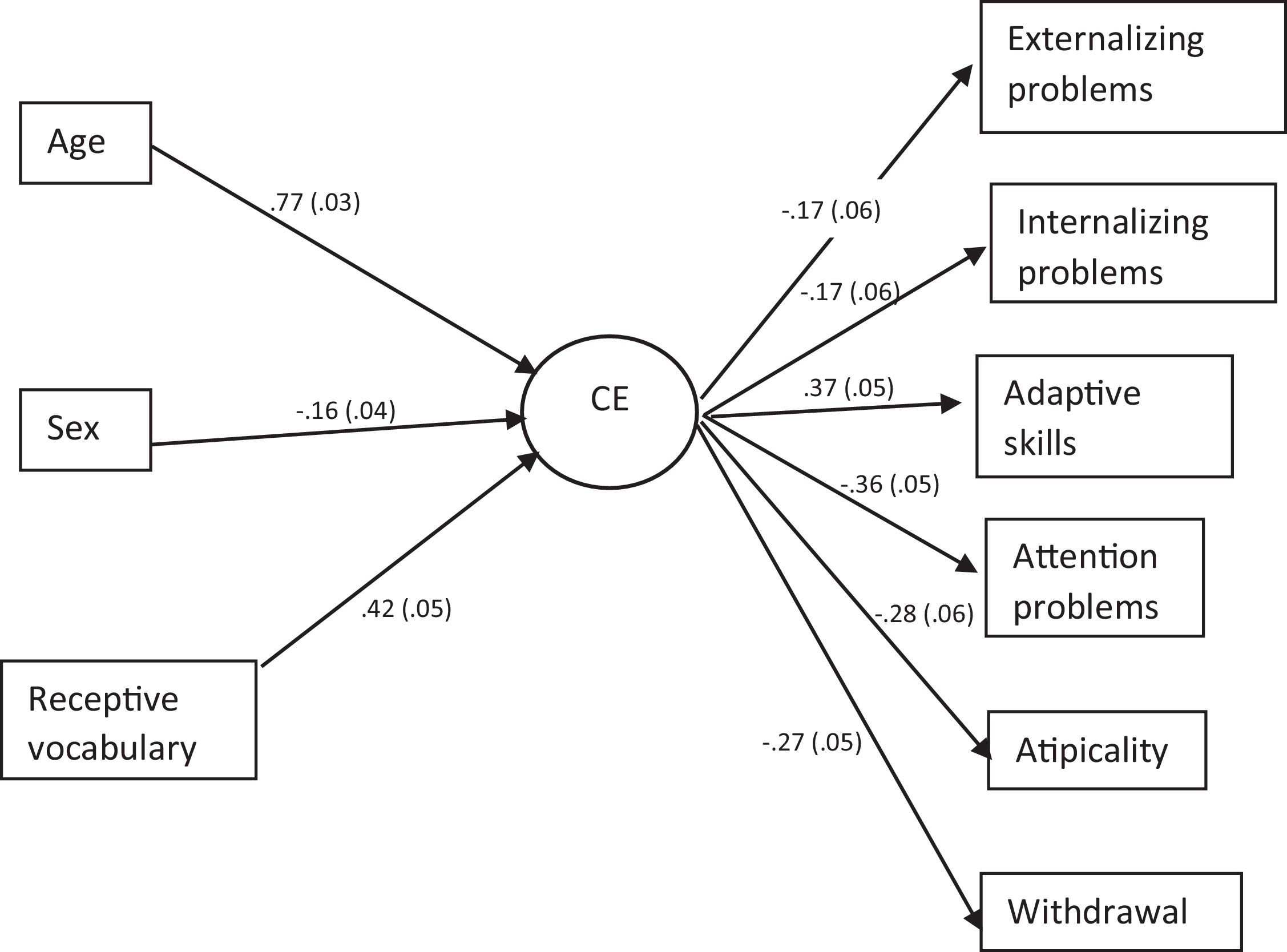

Predictive capacity of age, sex and receptive vocabulary for EK and the influence of EK on behavioral dimensionsAfter confirming the invariance of the instrument across language versions, we used a structural equations model with the entire sample to explore our hypotheses, taking age, sex and receptive vocabulary as predictors of EK and EK as a predictor of the behavioral dimensions analyzed. The model was found to have an adequate fit: χ2 (920) = 1064.53, CFI = .913, TLI = .906, RMSEA (90% CI) = .019 (.013, .023). Figure 1 presents the structural model, along with the standardized coefficients and standard errors corresponding to the associations between the latent and observed variables.

In terms of the variance explained in relation to the endogenous latent variable EMT, the value returned was .60, with a standard error of .05 (p < .001). All coefficients were statistically significant. The results indicate that age, sex and receptive vocabulary all influence EK. Girls scored higher for EK, as did older children and those with higher levels of receptive vocabulary. Furthermore, children with better EK were found to have fewer externalizing, internalizing and attention problems and lower levels of atypicality and withdrawal. Finally, higher levels of EK were associated with better adaptive skills.

DiscussionThe results of the present study provide evidence regarding the characteristics and properties of the Emotion Matching Task (EMT) for use in bilingual contexts in which both Spanish and Basque are spoken. This evidence will help advance both basic research into the processes involved in EK and applied research focused mainly on evaluating the impact of interventions on EK development.

First, the results suggest the suitability of using three of the four subscales proposed by the authors of the original instrument. The emotion recognition subscale (EMT 4) was found to be too easy for children in the age groups studied here, resulting in a ceiling effect in the scores. This subscale may of use in samples of children diagnosed with development problems, or may serve to help determine whether certain extreme scores in the rest of the instrument are due to the respondent in question having some kind of problem linked to the acquisition of emotional skills. Consequently, and in light of the results presented here, we suggest administering the original version of the EMT (Morgan et al., 2010) and, depending on the profile of the sample and the results obtained in the emotion recognition subscale, eliminating said subscale from the overall computation of the scores. Moreover, the administration of the entire instrument (i.e., all four subscales) will not only enable the cross-cultural comparison of the results obtained in different cultural contexts (Alonso-Alberca et al., 2020), but will also help confirm our findings pertaining to EMT 4.

Second, the results of the present study indicate that the EMT offers measurement invariance in relation to the two co-official languages of the Basque Country, along with a factor structure that is consistent with the theoretical construct proposed by the original authors, thereby confirming our first hypothesis. The psychometric properties of the instrument are adequate and provide evidence of validity, since they replicate the results obtained in previous studies, including the fact that EK improves with age and level of receptive vocabulary (Harden et al., 2014; Hoemann et al., 2019; Nook et al., 2020; Sarmento-Henrique et al., 2020), a finding that confirms our third hypothesis.

The study also provides evidence that the Spanish and Basque versions of the EMT are invariant in terms of sex, thereby indicating the absence of sex bias and confirming our second hypothesis. After ruling out this bias, the results obtained indicate that girls have higher EK levels than boys, a finding that confirms our third hypothesis. This is consistent with the results reported by most studies carried out to date (Alwaely et al., 2021; Bennett et al., 2005; McClure, 2000; Voltmer & von Salisch, 2017), although some authors continue to find no sex differences in this sense (Conte et al., 2019; Fidalgo et al., 2018).

We can therefore conclude that the EMT is an adequate instrument for evaluating EK among children aged between 3 and 6 years. It is easy to administer, requires only a low level of verbal agility and is attractive to children in this age range. Moreover, it complies with the criterion of collecting information directly from children themselves (Alonso-Alberca & Vergara, 2018; Denham, Ferrier et al., 2020; Trentacosta & Fine, 2010), something that is difficult at this age due to constraints linked mainly to language development. This makes it even more important to offer an instrument for evaluating EK that is adapted to the bilingual cultural context in which this study was carried out (Dewaele, 2012; Pavlenko, 2012). The present study offers an instrument in Basque with these characteristics, designed especially for use with children. Alongside the Spanish version of the EMT, it enables children’s emotional skills to be assessed in both official languages of the Basque Country.

The results of our study confirm the predictive capacity of EK in terms of behavior (hypothesis number four). As well as constituting further evidence of the validity of the EMT, this finding suggests that good EK may serve as a protective factor against internalizing, externalizing and attention problems, as well as atypicality and withdrawal (Fernald et al., 2017). Similarly, EK is associated with better adaptive skills, or in other words, with better social skills and the ability to adapt to different situations. These results pertaining to the relationship between EK and behavioral indicators corroborate previous findings (Domitrovich et al., 2017; Ekerim-Akbulut et al., 2020; Izard et al., 2001; Lafay et al., 2023; Trentacosta et al., 2022; Voltmer & von Salisch, 2017; Zhang et al., 2024) and confirm the benefits of fostering good emotional skills early on in life through educational intervention (LoBue et al., 2019; OECD, 2015).

The results outlined above highlight the importance of designing and implementing emotional education programs aimed at strengthening the protective effects of emotional skills from a very young age (Eisenberg, 2020; Hoffmann et al., 2020; LoBue et al., 2019; OECD, 2015, 2021). This in turn will help prevent the emergence of problems associated with a deficit of EK and poor emotion regulation, thereby helping to reduce behavioral problems. Furthermore, the explicit inclusion of emotional competence in the Spanish school curriculum (Organic Law 3/2020) constitutes an excellent opportunity, the benefits of which will be felt not only during the life stage in which said contents are taught, but in the medium and long term also (Denham et al., 2014).

It is therefore important to provide the education system with emotional competence intervention strategies whose efficacy is supported by sufficient evidence (Wigelsworth et al., 2010). To this end, it is vital to assess the results obtained using instruments with verified validity and reliability (Alonso-Alberca & Vergara, 2018; Denham, Ferrier et al., 2020) and indeed, this was one of the aims of the present study, namely to offer an instrument in Basque that, alongside the previously validated version in Spanish, will enable children evaluated in the Basque Country to choose the language in which they perform the test (International Test Comission, 2017).

Limitations and future researchThe principal limitation of the present study is its cross-sectional design, which prevents inferences being made regarding how the development of EK influences adaptive and maladaptive behavior in subsequent developmental stages. Longitudinal studies are required to test the hypothesis that the early development of emotional skills influences psychosocial adjustment in later life stages (Woodard et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2024). A second limitation is linked to the fact that the sample was not representative of the entire population of the Basque Country, among other reasons because in order to guarantee monolingual proficiency in Spanish, the Spanish-speaking sample comprised children resident in Madrid. Consequently, after analyzing the psychometric properties of the EMT, it would be interesting to replicate the study in both languages with a sample drawn entirely from the Basque Country, in order to guarantee the representativeness of the results.

Now that we have an instrument such as the EMT adapted to the bilingual context of the Basque Country, future studies may wish to implement an emotional skills education program and assess its effect both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, not only in terms of its ability to improve said skills, but also in relation to its impact on adaptive and maladaptive behavior. The aim of such an intervention would be to promote protective factors and improve psychosocial adjustment from early childhood onwards, as well as to provide educators with the resources they need to respond to the objectives outlined in Spain’s current education law (Organic Law 3/2020). Finally, in order to conduct longitudinal studies of this kind, it is necessary to develop instruments adapted to the linguistic context of the Basque Country that are capable of evaluating EK during later stages than the one on which the EMT focuses.

Despite the limitations outlined above, the present study offers a freely-available bilingual instrument with adequate psychometric properties that will enable the scientific community to advance the study and assessment of emotional competence during childhood.

FundingThe study was funded by Basque Government subsidies to Research Groups within the Basque University System (Code: IT1493-22).

CrediT authorship contribution statementNatalia Alonso-Alberca: Conceptualisation; data management; formal analysis; research; methodology; project management; resources; software; supervision; writing functions - original draft; and writing - review and editing.

Ana I. Vergara: Conceptualisation; formal analysis; obtaining funding; research; methodology; resources; software; writing functions - original draft; and writing - review and editing.