This study examines the effect of the congruence of gender role identity (androgynous/non-androgynous) and gender management characteristics (communal/agentic) on the quality of leader-member exchange (LMX); also whether authentic management is a variable that moderates this relationship. The study hypothesized the existence of a positive relationship between gender role identity and gender management characteristics with the quality of LMX. An additional hypothesis was that authentic management moderates and explains this relationship. The sample included 120 women subordinates managed by women. The respondents completed a questionnaire, in which they were requested to evaluate and describe their perception of their manager according to the study variables: gender role identity (androgynous/non-androgynous), gender management characteristics (communal/agentic), the quality of LMX, and the degree of authenticity that characterized their management style. At the same time, 24 managers were asked to complete a questionnaire that dealt with the quality of their leader-member exchange (LMX). The findings supported all of our hypotheses and indicated a positive relationship between the variables. When gender role identity and gender management characteristics are congruent, the quality of LMX is perceived as higher. In addition, we found that authentic management is indeed a moderating variable. That is to say, the relationship between the congruence of gender role identity and gender management characteristics and LMX is moderated and explained by authentic management. Additional findings point to the gap between managers and subordinates when evaluating and reporting LMX. When no congruence was found, there was a gap between the managers’ and subordinates’ reports, i.e., the managers evaluated LMX as higher. On the other hand, when congruence was found there were no significant differences between subordinates’ and managers’ reports regarding LMX.

Este trabajo analiza el efecto de la congruencia de la identidad del rol de género (andrógina/no andrógina) y las características de género de la gestión (comunitaria/egocéntrica) en la calidad del intercambio lídersubordinado (LMX), así como que si la gestión auténtica es una variable que modere dicha relación. El estudio plantea la hipótesis de una relación positiva entre la identidad del rol de género y las características de género de la gestión con la calidad de la LMX. Otra hipótesis ha sido que la gestión auténtica modera y explica esta relación. La muestra constaba de 120 mujeres dirigidas por otras mujeres. Cumplimentaron un cuestionario en el que se les pedía evaluar y describir su percepción de su jefa de acuerdo a las variables del estudio: identidad del rol de género (andrógina/no andrógina), características de género de la gestión (comunitaria/egocéntrica), la calidad de la LMX y el grado de autenticidad característico de su estilo de gestión. Además se pidió a 24 directivos que cumplimentasen un cuestionario sobre la relación líder-subordi nado (LMX) que les caracterizaba. Los resultados avalaban todas nuestras hipótesis, señalando una relación positiva entre las variables. Cuando la identidad del rol de género y las características de género de la gestión eran congruentes se percibía que la calidad de la LMX era superior. Además se encontró que la gestión auténtica es realmente una variable moderadora; es decir, la relación entre la congruencia de la identidad del rol de género y las características de género de la gestión y la LMX es moderada y explicada por la gestión auténtica. Otros resultados revelan la brecha entre líderes y subordinados al evaluar la LMX e informar sobre ella. Cuando no se hallaba congruencia había una brecha entre los informes de los líderes y de los subordinados; es decir, los primeros evaluaban mejor la LMX. Por otra parte, cuando había congruencia no había diferencias significativas entre los informes de subordinados y líderes en relación a la LMX.

Is there such a thing as “feminine” management? Do women and men behave differently as managers? This question has been studied extensively, yet is still controversial. Nevertheless, there is consensus that women encounter more obstacles to become managers, particularly management roles that are perceived as masculine (Mor, Mehta, Fridman, & Morris, 2011).

The March 2011 edition of the Status management journal dealt with this question and was entirely devoted to the issue of feminine management. The introduction was written by Rachel Ben-Zvi, CEO of “Motto-Mass Communication”, who manages 170 employees of which 90% are women. She claims that there is no such thing as “feminine” management; there is “natural” management, in which one needs not make an effort to become a management-bully in order to help employees to become a better version of themselves.

So, who is a good manager? Ben-Zvi used a parable to answer this question: “A good manager is one who can be an octopus and a wild horse at the same time. A wild horse is motivated by the urge to be first, to rebel against conventions; it is determined, passionate, and focused on the desired outcome. In parallel to the organizational world: to lead a vision and a strategy. And how does the octopus fit in? In the ‘how’ – the tactics – by achieving the daily balance, reinforcing the weak arms with strong arms, and controlling the workload and the pressure that allow the organization to move ahead securely.”

It can be said that this parable includes the combination of the main variables of the present study: gender management styles and their integration, and, of course, the result: achieving sound leadermember exchange based on trust, security, and reciprocity. The parable primarily emphasizes the variable that is at the core of this study: “natural” management, that is to say, authentic management. Nowadays, the demand for this type of management is increasing, and authenticity is becoming a valued asset in the organizational world.

Most research on this issue has addressed the role of charisma rather than authenticity. However, some studies have shown the link between awareness/authenticity and charisma. An aware manager can influence his or her subordinates and be appreciated by them (Hsiung, 2011). Therefore, when women adopt behavior that is contrary to their gender identity, it can be seen or interpreted as inauthentic or “by script”. Thus, a female manager is perceived as “real” or “playing a role” according to the awareness and sincerity that she displays (Kawakami, White, & Langer, 2000).

Recent studies (Kark, Waismal-Manor, & Shamir, 2012; Koenig, Mitchell, Eagly, & Ristikari, 2011) have indicated that both men and women in the labor force assume characteristics that are typical of the other gender. But, whereas men use “feminine” qualities as an additional means to gain control and satisfaction, women do not enjoy the advantage of flexibility and integration, thus creating a new asymmetry between men and women in the labor force (Mor et al., 2011).

This asymmetry takes discussion of this issue one step forward, because its roots are actually in the integration rather than in the conflicting expectations and stereotypes of gender and role, which are usually prominent in related studies. Therefore, in the present study we have chosen to focus on an androgynous group of women that combine “male” and “female” characteristics, and to examine whether authentic management style can balance the consequent asymmetry and serve as a solution for women managers.

Theoretical ReviewCongruence of gender role identity (androgynous/nonandrogynous) and gender management characteristics (communal/agentic)Congruence and its components. Discussion of the variable “congruence” requires decomposition and definition of its components in order to create its subsequent conceptual reconstruction. In regard to the present study, congruence means that female managers act according to expectations and beliefs attributed to them by their gender and according to their perceived gender identity. The assumption is that women make an effort to match their gender role to their management role despite frequent contradictions, which might form a management style that is different than men's (Rosette & Tost, 2010).

Gender role identity (androgynous/non-androgynous). Gender roles in society are shared expectations and beliefs that are attributed to individuals based on their gender. Gender roles include rights and obligations that are defined as befitting men and women in society. Gender roles affect behavior not only because men and women react to society's expectations, but also because most people internalize their gender roles (Eagly and Johanneson, 2001).

Androgyny is defined as the degree of one's psychological flexibility regarding gender-related stereotypical behaviors, namely, women that combine male and female stereotypical behaviors. Operationally, based on Bem (1974) Sex Role Inventory, an androgynous woman manager receives high scores on both the female and the male scales (Kark et al., 2012).

Gender management characteristics (communal/agentic). Managers are affected not only by their place in the hierarchy, but by their gender roles. There is agreement today that gender roles boil over to organizations, and therefore gender serves as an “identity background” in the workplace (Eagly and Johanneson, 2001). On the basis of the Social Role Theory regarding gender differences and similarities, expectations from leaders based on their categorization as male/female are usually defined as either agentic (a style attributed mainly to men and described as assertive, controlling, and confident) or communal (a style attributed mainly to women and described as being helpful, kind, gentle, sympathetic, and sensitive to others) (Eagly et al., 2000).

Do men and women act differently as managers? This has been a very controversial question for many years in the academic and organizational worlds. However, there is general consensus that women encounter more obstacles to becoming managers, probably because management roles invariably incorporate the dominance of male characteristics (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Koenig et al., 2011).

Studies on this topic range from traditional perceptions that male and female management styles are totally diverse to social perceptions that suggest minimizing the importance of gender differences (Eagly and Johanneson, 2001). Three main trends can be identified. First, the traditional dichotomous point of view that basically says: “Think manager – think man”, which is based on gender stereotypes. Second, a more modern outlook, which claims that effective leadership in fact requires skills that are stereotypically perceived as “feminine” (Duehr & Bono, 2006; Kark et al., 2012). The explanation of this outlook is that “feminine” leadership is more suitable to modern organizations. The third trend, typical of most recent research and the focus of the present study, is the understanding that the combination between both management styles is what creates effective leadership (Rosette & Tost, 2010; Vinkenburg et al., 2011).

We will try to break away from the traditional dichotomy and explain management differences between men and women in a social and organizational context that fits the third trend mentioned above.

Theoretic rationale of similarities and differences in gender management styles. The theoretic rationale derives from the Social Role Theory regarding gender-related similarities and differences, according to which expectations from managers or leaders are based on their categorization as male or female (Eagly and Johanneson, 2001). Thus, this approach assumes the existence of gender stereotypes.

Gender stereotypes are simplistic generalizations about the gender attributes, differences, and roles of individuals and/or groups. The typical distinction is that women are perceived as more “communal” and men as more “agentic” (Duehr & Bono, 2006).

Agentic style is generally attributed to men. It is depicted as assertive, controlling, and confident, and is expressed by aggression, ambition, belligerence, independence, daring, competitiveness, and self-confidence. In the work and management world it means: assertiveness, competition for attention, task-orientation, and focus on the problem to find solutions (Eagly and Johanneson, 2001).

Communal style is attributed to women, and is usually described in terms of sharing and concern for others, i.e., to be useful, to be gentle and kind, to help, to be sympathetic, and to be sensitive to others. In the work and management world it is expressed as: hesitant speech, not drawing attention to oneself, accepting the other, providing support and help, finding solutions for personal problems, and focusing on the process rather than the task and bottom-line (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Rosette & Tost, 2010).

The differences between the styles and their gender attribution form the general opinion that a good manager is aggressive, competitive, self-confident, independent, and has a great deal of control. This approach is gender-oriented, and thus assumes that women lack these qualities. Furthermore, women are perceived as less controlling and more cooperative than men. Male managers are described as unemotional and analytic, whereas women are viewed as intuitive and empathetic (Hayes & Allinson, 2004).

Moreover, Dickerson (2000) argues that these differences explain why women are under-represented in management positions. Apparently, they lack the male abilities that are perceived to produce effective, successful managers. Whether or not this is true and whether it is a result of social structuring, it affects women's place in management hierarchy and their own self-esteem (Hayes & Allinson, 2004). Confirmation of this can be found in a recent study that examined the existence of these stereotypes. The results indicated that 72% of all women in senior managerial positions claimed that stereotypes regarding job expectations and women's abilities were their main, most significant obstacle to senior management positions (Koenig et al., 2011). Other studies over the years were harsher in their assessment, claiming that it is just about impossible to change these stereotypes, even in view of awakening social changes (Duehr & Bono, 2006).

It is clear today that the social environment concerning respect for women has changed, expressed in the organizational environment primarily by giving more women the opportunity to climb the corporate ladder and by making diversity a business goal. The inevitable questions are: can the mentioned social changes break the glass ceiling?; can they alter gender stereotypes?

Congruence: A simultaneous perception of gender roles and management roles. In view of the above, it is obvious that managers are affected not only by their place in the hierarchy but also by their gender roles.

Scholars agree today that gender roles boil over to organizations, and therefore gender serves as an “identity background” at the workplace (Eagly and Johanneson, 2001). What is more, studies conducted in the field have concluded that there is not much new under the sun: although some stereotypical gender differences were eroded by organizational roles, some are still alive and kicking and can be seen on a daily basis (Eagly, 2005). Another study, which examined behaviors in a wide variety of work definitions, found that behaviors categorized as agentic were observed between the participants and the supervisor rather than the boss. On the other hand, communal behaviors were affected by the participant's gender regardless of status, and women tended more to this type of behavior, especially with other women (Eagly & Karau, 2002).

In this context, congruence means that women managers act according to gender expectations and beliefs, and their perceived gender identity. Gender role has various implications to men's and women's behavior as managers, not only because of the different content of men‘s and women's roles, but primarily because of the inconsistencies between the communal traits expected of women and the belief that agentic qualities are required in order to succeed as a manager in the corporate world (Rosette & Tost, 2010).

Thus, incongruence between gender and management roles tends to create prejudices against women managers in two ways:

- a.

Women are not perceived as having ‘management potential’ because management abilities are stereotypically attributed to men.

- b.

Women are perceived as possessing lesser leadership abilities because agentic behavior is attributed more to men than to women (Eagly and Johanneson, 2001).

Analysis of congruence and incongruence sheds new light on the discussion, as it clarifies the insight that promoting women to managerial jobs is limited by threats from two directions: on one hand, women must conform to their gender roles, which could cause them to fail to meet the requirements of their managerial position; on the other hand, conforming to their management role could cause them to fail in their gender role (Koenig et al., 2011). Thus, for instance, women could encounter more negative reactions if they choose agentic-style behavior, because it includes power and control over others (Mor et al., 2011).

We can sum up and say that gender roles are evident in organizations. Female managers’ gender identity could easily lead to behaviors that clash with their gender role (Eagly & Karau, 2002). Therefore, it is harder for women, because their gender role does not necessarily match their management role, which creates obstacles and prejudices for women managers (Duehr & Bono, 2006).

Androgyny and the “winning combination”. In recent years, the discussion of stereotypes has decreased and has moved on to concepts of agentic and communal styles, and the degree to which women adopt the former, more masculine style (Rosette & Tost, 2010). Studies over the years have found an increase in women's statements that they adopt traits that were previously considered male, primarily due to the social climate for women, and which is significantly expressed in the workplace (Duehr & Bono, 2006; Hayes & Allinson, 2004).

The common assumption today is that men and women who can combine “male” and “female” characteristics derive considerable benefits, as the combination allows them to switch between traits according to context rather than remaining chained to a specific range of behaviors (Mor et al., 2011).

In view of the above, one can assume that this “androgynous” ability could serve as a solution for women in management positions, and solve the inherent incongruence between gender and management roles (Rosette & Tost, 2010).

But, is it enough? Can androgyny make the difference, or rather obscure it? Recent studies (Kark et al., 2012; Mor et al., 2011) indicate that when managers combine characteristics and adopt an androgynous gender identity, men still have an advantage. Furthermore, Mor et al. (2011) assert that women derive usefulness only from “male” traits, since their sense of control over their life depends on instrumental rather than expressional traits.

Kark et al. (2012) add the surprising finding in this context, namely that not only do they derive less benefit, but women pay a higher price when they are diagnosed as non-androgynous compared to non-androgynous men.

Is it enough for women? The discussion of this question follows.

Authentic ManagementAuthentic management – now more than ever. In their fascinating book Authentic Leadership, Goffee and Jones (2005) describe what they call a unique modern obsession – the search for authentic leadership and its manifestations in the corporate and organizational world. It symbolizes the disenchantment with the skilled “apparatchik” or talented follower. Moreover, in a world in which “real” has become unrestrained “reality”, and virtual communities fill the void created by the demise of real community life, the desire for authenticity is evident (Goffee & Jones, 2005). This criticism of modern life has been heard often, but it is particularly relevant in the workplace.

The recently increasing interest in authentic leadership boils over to organizations in the form of authentic management. It has been said that the unique stressors in modern-day organizations require a new leadership approach, which should rehabilitate basic security, hope, optimism, and meaning (Avolio et al., 2004).

What is authentic management? The concept of authenticity has its roots in Greek philosophy (“To thine own self be true”) (Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Humanist psychologists such as Maslow defined authentic people as self-actualizing people, congruent with their basic nature, who see themselves and their life clearly and precisely. Since these people are not motivated by others’ expectations, they can make decisions that are compatible with their inner voice.

One should not make the common mistake of confusing authenticity with sincerity. Erickson (1995) made the distinction, defining sincerity as “congruence between avowal and actual feeling”, that is to say, sincerity is measured or judged by how the self is represented accurately and honestly to others, rather than the extent to which one is true to the self.

Authentic leadership was conceptualized in the field of positive psychology, and was developed by Avolio (2003) and Avolio and Gardner (2005), who define authentic leaders as people who are deeply aware of their thoughts and behavior and are perceived by others as aware of their own values, knowledge and power, and that of others; they are aware of the context in which they operate and seem secure, hopeful, optimistic, and resilient.

Authentic leadership and authentic management – the organizational world. The work world in recent years is characterized by unique pressures, dynamics, challenges, and a constant determination to create a competitive edge. Organizations have consequently realized that they need authentic leaders/managers (Hsiung, 2011). In this context, Avolio and Gardner (2005) defined authentic leadership in the organizational world as “A process that draws from both positive psychological capacities and a highly developed organizational context to foster greater self-awareness and self-regulated positive behaviors on the part of leaders and associates, producing positive self-development in each” (Avolio & Gardner, 2005, p. 321). Beyond the breadth of this definition, it holds a built-in challenge – How does one measure authentic leadership? Shamir and Eilam (2005) addressed the breadth of the above-mentioned definition by defining four characteristics of authentic leaders:

- a.

Authentic leaders are true to themselves.

- b.

Authentic leaders are not motivated by external benefits such as personal gain, status, or honor.

- c.

Authentic leaders are the original, not the copy, and come to their convictions through their own internal processes.

- d.

Authentic leaders’ actions are based on their personal values. In this context, they defined the subordinate of an authentic leader/manager, as one who follows for authentic reasons and conducts an authentic relationship with him or her.

The described characteristics are compatible with the four measures of authentic management that are the basis for the Authentic Leadership Questionnaire developed by Avolio, Gardner, and Walumbwa (2007) that includes 16 statements (Hsiung, 2011):

- a.

Self-awareness – knowing oneself and one's strengths and weaknesses.

- b.

Transparency – presenting one's authentic (rather than fake) face to others.

- c.

Balanced processing – considering all relevant data before making a decision.

- d.

Ethics/morals – internalized and integrated self-regulation.

Goffee and Jones (2005) take this discussion one step forward by stating that a manager cannot identify him/herself as an authentic leader. Only subordinates who have experienced an authentic manager can perceive or describe them as such. In other words, authentic leadership can only be identified by others, and hence no manager can proclaim “I am authentic”.

Wanted: Authentic managers. Goffee and Jones (2005) assert that in the present, work has become a means to fulfilling external needs – paying off a mortgage, buying designer labels, etc., but is not a way of life that leads to discovering, building, and revealing the authentic self. The demand for authentic leadership exists, and it is ever increasing. Traditional hierarchies are crumbling, and only leadership can fill the void. In an earlier paper, Goffee and Jones (2005) propose two ways to manage authenticity: first, make sure that your words fit your actions, and second, find common ground with your people. You should see various sides, adjust to various situations, and play different roles, but they must come from your own personality. Playing roles does not mean faking. Subordinates invariably realize when their leader is faking it.

Modern organizations acknowledge the added value of authentic managers. When managers are authentic it affects their subordinates, which in turn affects their attitude to colleagues and customers, all of which are the basis for an organizational culture rooted in authenticity (Avolio et al., 2004). Furthermore, authentic leaders encourage diversity and know how to develop their subordinates’ abilities and empower them (Hsiung, 2011).

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) TheoryThe LMX theory focuses on the exchange between leaders and followers (Liden, Wayne, & Sparrowe, 2000; Scandura, 1999). According to this approach, the managerial pattern is different across subordinates and changes in keeping with the quality of the manager-employee relationship. The nature of this relationship determines the distribution of resources and time between managers and employees (Yammarino & Dubinsky, 1992; Yukl & Fu, 1999).

Within LMX theory, the quality of the relationship is assessed by managers and subordinates alike. A high-quality relationship is characterized by a high level of information exchange, high level of trust, respect, fondness, extensive support, high level of interaction, mutual influence, and numerous rewards. A low-quality relationship is characterized by a low level of trust, formal relations, one-directional influence (from manager to employee), limited support, a low level of interaction, and few rewards (Bauer & Green, 1996). Hence, the essential core of LMX theory is an understanding of the different types of exchange between leaders and followers. Accordingly, as patterns of exchange constitute an important basis of relationship development, types of exchange relationships can cause followers to behave in certain ways. In other words, in a high-level exchange, managers develop a kind of trusted in-group with their employees and in a low-level exchange the manager-employee relationship is basically supervisory and less personal in nature. Leaders functioning within a trusted in-group also delegate responsibility, which may take place prior to the development of the relationship as a method of assessing trust and capabilities, and later as a way of rewarding employees and expressing approval of their work.

Liden et al. (2000) findings show that the quality of interpersonal relationships between managers and employees has an impact on the employees’ sense of empowerment. Gómez and Rosen, 2001 also found a significant relationship between LMX and employees’ empowerment. Members of the in-group feel more empowered than members of the out-group, since the manager, by delegating more authority and responsibilities to members of the in-group, grants them more emotional support and includes them in the decision-making process. Moreover, employees who maintain high level LMX demonstrate greater responsibility toward the organization, and therefore contribute more. In addition, a high level of exchange mandates mutual trust, support, and loyalty between leader and employees (Asgart et al., 2008). However, even within the context of in-group and out-group distinctions, Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995) claims that managers should afford all their subordinates access to LMX processes by at least attempting to create two-way LMX with them. As such, when dealing with a high level of exchange, managers aim at the highest social needs of their employees, thus encouraging them to place the collective interest above and beyond short-lived gratitude (Uhl-Bien and Maslyn, 2003). Studies also show that the manager's fairness can create positive social exchanges (Wayne et al., 2002). Furthermore, the findings of Sweetland and Hoy (2000) suggest employees who were given knowledge and granted freedom of action from their managers, and were involved in decision-making, felt more empowered than employees who were not granted these actions by their managers.

The LMX theory is fundamentally sociological and based on the Social Exchange Theory (Blau, 1964), which establishes human relationships on diverse exchanges. These exchanges may be economic, social, political, or emotional. Reciprocal relationships based on these types of exchange build a relationship between two parties on diverse levels of intensity, depending on the type of exchange. In addition, recent studies indicate a link between LMX and the efficacy of reducing resistance to change. Thus, for example, Furst and Cable (2008) show that high LMX mitigates the link between the use of ingratiation tactics and resistance to change among employees. According to this study, the relationship is not unequivocal and is not always exposed. For change tactics such as sanctions and legitimization, no significant relationship was found between LMX and reducing resistance to change. In a similar fashion, the leader-follower exchange creates a relationship of mutual influence, while negotiating the role of the follower within the organization. The more the relationship develops, the more the freedom of action granted to the follower can expand. This freedom of action empowers employees. This notion is reinforced by Liden et al. (2000), who found a significant relationship between leader-follower exchange and the employees’ perception of their level of empowerment. Thus, it seems that the leader-follower exchange is positively related to positive attitudes toward work, such as job satisfaction.

Relationships between VariablesThe relationship between the congruence of male and female gender roles and management characteristics, and authentic leadership. Despite achievements in the arena of women's status and the development of various feminist theories, men are still considered better managers than women, primarily because the perceived successful management style is male. Qualities such as independence, self-confidence, assertiveness, dominance, and rationality, which are typical of the agentic style (Eagly, 2005), have been and still are attributed only to men. Both men and women have defined a good manager this way (Schein, 2007).

Therefore, women managers face a paradox: If they adopt a male management style, their subordinates will not like them. If they adopt a warm, feminine management style, they will be liked but not considered strong and respected (Eagly, 2005; Mor et al., 2011). When women achieve senior management positions and leadership, their success is not perceived as immediate and it takes them longer than men to be recognized. If they adopt behavior norms that are contrary to their gender, they might be successful or even be perceived as charismatic, but the price they pay is dislike and being seen as an outsider. Women get a negative response if they exert authority. Moreover, many people view the use of power, persuasion, and determining an organization's agenda as outside women's realm (Carli, 2001).

These trends are compatible with what was described as congruence between female gender role identity and appropriate gender management characteristics, or the incongruence of adopting a male management style. Thus, incongruence could provide an explanation for the challenges encountered by women managers.

All the same, a recent school of thought claims that management has become more “feminine”, and characteristics that were previously considered female stereotypes are now identified with effective management (Duehr & Bono, 2006). Economic, demographic, technological, and cultural changes have created an alternative approach that views traditional management styles as less effective. The contention is that precisely because of these changes, managers are required to be more flexible, cooperative, empathetic, and committed, and to put an emphasis on employee development and empowerment (Kark, 2004). Consequently, effective leadership can no longer be defined exclusively in male terms, but as androgynous, combining female and male styles that can provide more flexibility and an advantage for both genders in management roles (Kark et al., 2012).

The transition to androgyny might make things easier for women's incongruence (between gender role and management role) problem, and allow them to cope better with the double paradox: contradicting expectations that women adopt the agentic management style to fulfill their corporate role, but at the same time act “communally” to fulfill their gender role. Additionally, when women behave in a way that is incongruent with their gender role, it could be interpreted as inauthentic and “by script”. Therefore, women that do not have androgynous characteristics yet adopt a male management style because it is expected of them, are considered fakes and disliked, because there is incongruence between their identity and management style (Rosette & Tost, 2010). Women also pay a higher price than men do when incongruence is perceived between their role identity and management characteristics (Kark et al., 2012).

In this context, a female manager's awareness and sincerity are important, and therefore – beyond combining management styles and androgyny – she must be perceived as an authentic manager in order not to pay the abovementioned price. This aspect sheds new light on the discussion, because the premise of authentic management is being true to oneself and less concerned with others’ expectations and actions based on personal values (Shamir & Eilam, 2005). Therefore, the awareness and sincerity exhibited by the female manager and the degree to which she is perceived as real and authentic or “playing a role” are what counts (Kawakami et al., 2000). The congruence between androgyny and a combined male/female management style could help women managers to be seen as more authentic than others that adhere to one style, and especially those that adopt a style that is contrary to their gender identity. In view of the above, it can be assumed that women with an androgynous gender role that combine agentic and communal characteristics will be perceived as more authentic than their counterparts that do not combine styles and are less androgynous.

Hypothesis 1Women managers that are perceived by their subordinates as having an androgynous gender role identity and combined agentic and communal management style will be perceived as more authentic managers than others.

Authentic management and LMX. Leadership, by definition, is a system of interactions. The early Trait Theory ignored the fact that a relationship is actively built by both parties. In reality, leadership is always a social construct that is recreated by the relationships between leaders and those they aspire to lead (Goffee & Jones, 2005). Avolio and Gardner (2005) claim that authentic management has a multi-dimensional impact on organizations, and referred to the levels of individual, group, and pair. The pair level relates to the exchange relationship between manager and subordinate (LMX). They state that authentic leadership/management can create a positive exchange relationship between managers and their subordinates.

Theoretically, authentic management focuses on the leader's behavior. LMX focuses on the congruence of the relationship between manager and subordinate. Since female managers are more willing to share information and to express their thoughts and inner feelings, they can create more trust, loyalty, and identification (Wang et al., 2005). Furthermore, their integrity and trustworthiness help them form long-term mutual relationships with their female subordinates, so that they act as partners with common expectations and goals (Hsiung, 2011). Thus, it can be assumed that authentic management will affect the quality of LMX, and that authentic leadership relates positively to the quality of LMX.

Hypothesis 2A positive relationship will be found between the degree of authentic management and the quality of LMX between female managers and their subordinates (as reported by managers and subordinates).

Authentic management as a moderator between the congruence of gender role identity-gender management characteristics, and leader-member exchange (LMX). We have noted that androgyny and integration of both management styles are not sufficient to serve as a solution for women managers who deal with a double set of expectations rooted in their gender and management identities. Since, as a rule, men lead groups, women are less perceived as the prototype of leadership. Consequently, when leadership is perceived in masculine terms, the demand is usually for masculine leaders irrespective of their gender (Rosette & Tost, 2010). Furthermore, if women become leaders and managers, their success is not perceived immediately, and it takes longer for them to gain recognition by their subordinates (Kark et al., 2012). If they adopt characteristics that are seemingly opposite to their gender (incongruence) perhaps they can achieve success and be perceived as charismatic, but they pay the price of being disliked and regarded as outsiders that act against expectations (Eagly, 2005; Kawakami et al., 2000).

In the last two years, research has moved the discussion a step forward by showing that whereas for men “feminine” characteristics serve as an additional means to achieve control, women do not enjoy this advantage. Namely, when both genders integrate male and female traits and develop androgyny, only men benefit from it, while women are seen in a negative light (Kark et al., 2012; Mor et al., 2011). This sheds new light on the discussion and creates a fresh asymmetry that women managers are forced to deal with.

The question, then, is: What, apart from an androgynous gender identity and combining male and female characteristics, can help women managers to be considered successful and to maintain high quality LMX with their subordinates?

Studies have found that women who are aware and authentic, and are able to combine management styles within context, can avoid this paradox. How so? Authenticity is based on awareness and sincerity, and therefore one can assume that the more aware and true to herself she is, the better she can influence her subordinates and gain their appreciation (Hsiung, 2011). The same parameters determine whether she is perceived as “real” and as a woman who integrates styles based on her values and management agenda rather than social desirability. Substantiation of this can be found in a study that concluded that women managers who are “masculine” in style yet aware, are perceived by men as more successful than women who adopt a male style but are not sincere and not aware (Kawakami et al., 2000). That is to say, even when women do not integrate management styles and adopt a male style out of awareness and congruence with their role identity (which in this case is male), their authenticity helps them to be seen as successful and sincere. Surprisingly, this viewpoint is common among women too, especially when regarding other women in senior management positions (Rosette & Tost, 2010).

In view of the above, adding the variable of authentic management promotes the explanation of the relationship between the variables: since authenticity is related to LMX, subordinates must identify with their manager and accept her values, which fit and serve the community/group that they belong to and in which the manager has authority (Goffee & Jones, 2005). It is not enough that managers are aware of their values; they must also believe that they serve their community. Namely, the leader must reflect their common ideas and values in order to gain her subordinates’ legitimization (Eagly, 2005). Additionally, legitimization by subordinates is necessary, because a manager cannot identify or declare herself as authentic. Authenticity is identifiable by others, so that only subordinates that have experienced an authentic manager can perceive her as such (Goffee & Jones, 2005). Thus, we believe that combination of styles and androgyny adopted by women managers reinforces the quality of exchange with their subordinates. Nevertheless, this is not the full solution, and authentic management can explain this relationship and contribute to it. Consequently, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3Women subordinates that perceive that their manager has an androgynous gender role identity and combined management style will report higher quality LMX than subordinates that do not perceive their manager so.

Hypothesis 4Women managers that are perceived by their subordinates as having an androgynous gender role identity and combined management style will report higher quality LMX than managers that are not perceived so.

Hypothesis 5Authentic management moderates the relationship between the congruence of gender role identity (androgynous/non-androgynous) – gender management characteristics (agentic/communal), and LMX.

Summary of HypothesesHypothesis 1: Women managers that are perceived by their subordinates as having an androgynous gender role identity and combined agentic and communal management style will be perceived as more authentic managers than others.

Hypothesis 2: A positive relationship will be found between the degree of authentic management and the quality of LMX between female managers and their subordinates (as reported by managers and subordinates).

Hypothesis 3: Women subordinates that perceive that their manager has an androgynous gender role identity and combined management style will report higher quality LMX than subordinates that do not perceive their manager so.

Hypothesis 4: Women managers that are perceived by their subordinates as having an androgynous gender role identity and combined management style will report higher quality LMX than managers that are not perceived so.

Hypothesis 5: Authentic management moderates the relationship between the congruence of gender role identity (androgynous/non-androgynous) – gender management characteristics (agentic/ communal), and LMX.

MethodParticipantsThe data were collected from 144 women, of whom 24 were managers and 120 were subordinates. Each respondent was asked to fill out a questionnaire that examined the relevant variables for managers and subordinates separately.

Subordinates. The mean age was 35.05 (SD = 9.4); the minimum age was 20 and the maximum age was 60; 68.3% were married, 25.8% single, 5% divorced, and 0.8% widowed; 79.2% of the subordinates were professional workers and 20.8% were administrative workers; 46.7% held a BA degree, 25% held a MA degree, 15% secondary education, and 13.3% high school education. The mean number of children was 1.46 (SD = 1.37, minimum number of children 0, maximum 6); 34.2% had no children, 41.7% had 1-2 children, 22.5% had 3-4 children, and 1.6% had 5-6 children.

Managers.The mean age was 37.29 (SD = 6.64); the minimum age was 24 and the maximum age was 60. Most (87.5%) were married, 6.7% were single, and 5.8% were divorced; 79.2% of the managers were mid-level management, 25% were senior management (directors), and 20.8% were junior management; 59.2% held a MA degree, 40% held a BA degree, and 0.8% had secondary education. The mean number of children was 1.87 (SD = 0.99, minimum number of children 0, maximum 4); 12.5% had no children, 58.3% had 1-2 children, and 29.1% had 3-4 children.

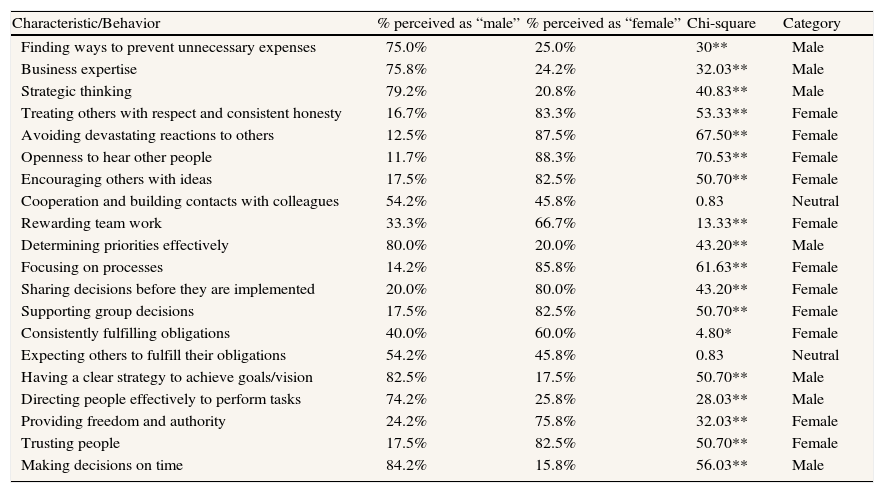

MeasuresSubordinatesIdentification of management patterns as “male” or “female”. An instrument was used to preliminarily identify general male and female management patterns as perceived by the subordinates. The instrument was developed by Annes (1997) as part of her thesis and includes 20 statements that describe behaviors and characteristics. The respondents were requested to categorize the statements in general (not about their own managers) as “agentic” (male) or “communal” (female). Table 1 presents an analysis of the responses. The results indicate that 7 of the examined characteristics were perceived as male, 11 as female, and 2 as neutral. These results served as a basis for consequently constructing the variables “agentic” and “communal” as male and female gender management characteristics.

Management characteristics categorized as male or female.

| Characteristic/Behavior | % perceived as “male” | % perceived as “female” | Chi-square | Category |

| Finding ways to prevent unnecessary expenses | 75.0% | 25.0% | 30** | Male |

| Business expertise | 75.8% | 24.2% | 32.03** | Male |

| Strategic thinking | 79.2% | 20.8% | 40.83** | Male |

| Treating others with respect and consistent honesty | 16.7% | 83.3% | 53.33** | Female |

| Avoiding devastating reactions to others | 12.5% | 87.5% | 67.50** | Female |

| Openness to hear other people | 11.7% | 88.3% | 70.53** | Female |

| Encouraging others with ideas | 17.5% | 82.5% | 50.70** | Female |

| Cooperation and building contacts with colleagues | 54.2% | 45.8% | 0.83 | Neutral |

| Rewarding team work | 33.3% | 66.7% | 13.33** | Female |

| Determining priorities effectively | 80.0% | 20.0% | 43.20** | Male |

| Focusing on processes | 14.2% | 85.8% | 61.63** | Female |

| Sharing decisions before they are implemented | 20.0% | 80.0% | 43.20** | Female |

| Supporting group decisions | 17.5% | 82.5% | 50.70** | Female |

| Consistently fulfilling obligations | 40.0% | 60.0% | 4.80* | Female |

| Expecting others to fulfill their obligations | 54.2% | 45.8% | 0.83 | Neutral |

| Having a clear strategy to achieve goals/vision | 82.5% | 17.5% | 50.70** | Male |

| Directing people effectively to perform tasks | 74.2% | 25.8% | 28.03** | Male |

| Providing freedom and authority | 24.2% | 75.8% | 32.03** | Female |

| Trusting people | 17.5% | 82.5% | 50.70** | Female |

| Making decisions on time | 84.2% | 15.8% | 56.03** | Male |

*p < .05, **p < .01

LMX was assessed using a 6-item questionnaire based on Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995). The respondents answered on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (low quality LMX with manager) to 6 (high quality LMX with manager). The variable was consequently calculated as the mean replies to the items (α = .907, M = 3.80, SD = 1.05).

Authentic leadership/management was gauged by means of the Authentic Leadership Questionnaire developed by Avolio et al. (2007). The questionnaire includes 16 items relating to the four measures of authenticity. Participants indicated the frequency with which they experienced the situation described by each item using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (all the time) (α = .944, M = 3.91, SD = 1.01).

Gender role identity was tapped using the Bem Sex Role Inventory (1974), which examines the respondents’ gender identity based on identification with various personal traits. We chose to use the Hebrew version, which was adapted to Israeli culture by Milgram and Milgram (1975), and consequently cited by Rosenberg (1991). The questionnaire includes 60 items, which respondents were asked to grade about their managers on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not characteristic at all) to 6 (very characteristic).

Male: α = .938, M = 4.11, SD = 0.98; female: α = .939, M = 3.86, SD = 0.98.

Gender management style was assessed reusing the preliminary questionnaire, but this time the respondents were requested to relate to their own manager on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (all the time). The goal was to characterize the management style perceived by the subordinate as agentic or communal.

Agentic: α = .881, M = 4.36, SD = 1.03; communal: α = .953, M = 3.37, SD = 1.21.

ManagersLMX was measured using the same questionnaire as the subordinates’ questionnaire. The manager was requested to answer about her subordinates and a separate questionnaire was filled out for each subordinate (α = .876, M = 4.26, SD = 0.72).

Goffee and Jones (2005) emphasize that one cannot identify one's own authenticity – only subordinates can describe him or her as such. Therefore, this measure was gauged only with the subordinate respondents.

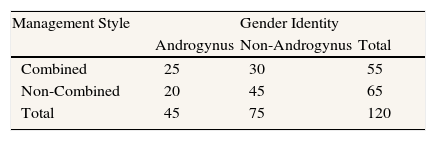

Congruence between gender role identity (androgynous/non-androgynous) and combined (communal + agentic) management style.

In the first stage, we built the variable “gender role identity” by categorizing two groups: A. androgynous – respondents that received a score higher than the median for male role characteristics (median = 4.4) and a score higher than the median for female role characteristics (median = 4.1); B. non-androgynous – all the others.

In the second stage, we constructed the variable “combined management style” by classifying two groups: A. combined – respondents that received a score higher than the median for “agentic” management (median = 4.57) and a score higher than the median for “communal” management (median = 4.0); B. non-combined – all the others.

In the third stage, we created the variable “androgynous and combining styles”, classified by two groups: A. congruent – respondents that were found to have androgynous gender role identity and a combined management style; B. incongruent – all the others.

Table 2 indicates that 20.8% of all the managers are perceived as both androgynous and having a combined management style.

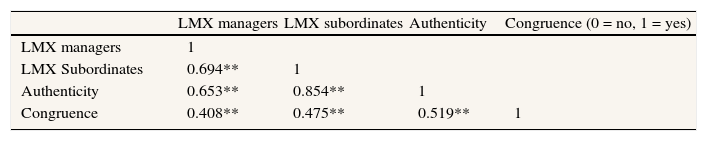

ResultsTable 3 presents the correlations of the study's variables, and we can observe that the variables are noticeably inter-correlated. Therefore, when examining hypotheses 2-4 we proceeded with Hotelling's T-squared tests rather than independent t-tests.

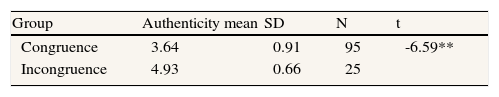

Women managers that are perceived by their subordinates as having an androgynous gender role identity and combined agentic and communal management style will be perceived as more authentic managers than others.

An independent t-test was performed to examine the first hypothesis. The independent variable was congruence of androgynous gender role identity and combined management style and the dependent variable was authenticity. Table 4 presents the comparison results of the managers’ degree of authenticity between those that were perceived as congruent with those that were not.

The findings confirm the first hypothesis, that is to say that the degree of authenticity among managers that are perceived as congruent (M = 4.93) is higher than that of managers that are not perceived as congruent (M = 3.64).

Hypothesis 2A positive relationship will be found between the degree of authentic management and the quality of LMX between female managers and their subordinates.

Hotelling's T-squared test was run between the two dependent variables – subordinates’ LMX and managers’ LMX, and the independent variable – authentic management. The reason for employing this test was the high correlation between the two dependent variables (r = .694, p < .01). The results were as follows: Hotelling's T-squared = 2.78, F(2, 117) = 163, p < .01.

We found a significant positive effect of authentic management on subordinates’ LMX, b = 0.889, p < .01, F(1, 118) = 317.63, and a significant positive effect of authentic management on managers’ LMX, b = 0.463, p < .01, F(1, 118) = 87.61. Hypothesis 2 was thus corroborated.

Hypotheses 3 and 4Hotelling's T-squared test was employed to examine hypotheses 3 and 4. The dependent variables were subordinates’ LMX and managers’ LMX, and the independent variable was congruence of androgynous gender role identity and gender management characteristics. The following results were obtained: Hotelling's T-squared = 0.311, F(2, 117) = 18.22, p < .01.

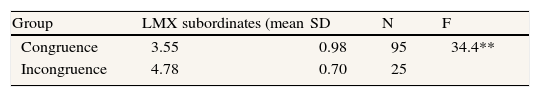

Hypothesis 3Women subordinates that perceive that their manager has an androgynous gender role identity and combined management style will report higher quality LMX than subordinates that do not perceive their manager so.

Table 5 indicates that a significant effect was found for the congruence of androgynous gender role identity and gender management characteristics on subordinates’ LMX, F(1, 118) = 34.4, p < .01.

The degree of LMX reported by subordinates with managers that are perceived as congruent (M = 4.78) was higher than the reported degree of LMX with managers that are not perceived as congruent (M = 3.55). Hence, hypothesis 3 was confirmed.

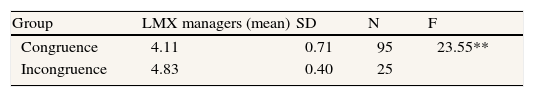

Hypothesis 4Women managers that are perceived by their subordinates as having an androgynous gender role identity and combined management style will report higher quality LMX than managers that are not perceived so.

A significant effect was found for the congruence of androgynous gender role identity and gender management characteristics on managers’ LMX, F(1, 118) = 23.55, p < .01.

Table 6 clearly shows that the fourth hypothesis was substantiated. Managers with higher congruence (M = 4.83) reported a higher level of LMX than managers that are not perceived as congruent (M = 4.11).

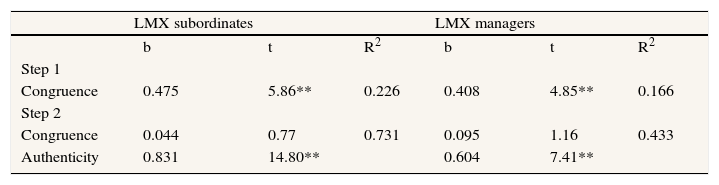

Hypothesis 5Authentic management moderates the relationship between the congruence of gender role identity (androgynous/non-androgynous) – gender management characteristics (agentic/communal), and LMX.

A two-step hierarchical regression was employed to examine the fifth hypothesis. In the first step, the independent variable was “congruence” and the dependent variable was “LMX”. In the second step, the variable “authentic management” was added as a possible moderator.

Table 7 indicates that the fifth hypothesis was corroborated. In the first step, a positive relationship was found between congruence and LMX subordinates, and between congruence and LMX managers (b = 0.475 and b = 0.408, respectively). In the second step, after we added authentic management as a moderating variable, the relationship between congruence and LMX subordinates and between congruence and LMX managers disappeared (b = 0.044 and b = 0.095, respectively). We can, thus, conclude that authentic management moderates the relationship between the congruence of gender role identity – gender management characteristics, and leader-member exchange (LMX).

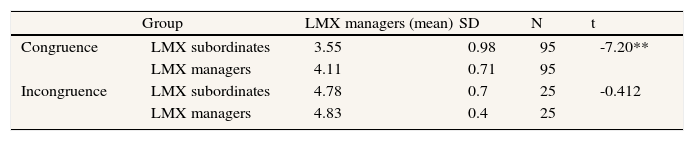

Additional findingsAfter reviewing the results, an additional question arose: would we find differences between the LMX perceptions of subordinates and managers, and could these differences be explained by the lack of perceived congruence? Separate t-tests were conducted for managers with perceived congruence and for managers that were perceived as incongruent.

Table 8 clearly indicates a difference. If there is no congruence between gender role identity and gender management characteristics, there is a gap between the reported LMX of managers and of subordinates. Equally, if there is congruence between gender role identity and gender management characteristics, no significant differences are found between the reported LMX of managers and of their subordinates.

DiscussionThe current study examined the relationships between the following variables: congruence of gender role identity (androgynous/non-androgynous) and gender management characteristics (agentic/ communal), the quality of leader-membership exchange (LMX), and authentic management. The study focused on the effect of the congruence of gender role identity and gender management characteristics on the quality of LMX, and whether authentic management moderated this relationship. We also asked if the “winning combination” was sufficient or if an additional component was required as a solution for women managers. To this end, we examined the effect of authentic management as a moderator, which shed new light on a discussion that has been the focus of much research.

Our findings indicate that all five hypotheses were substantiated.

Examination of the first hypothesis found that women managers that were perceived by their subordinates as possessing an androgynous gender role identity and combined management characteristics were perceived as more authentic leaders than others. Namely, a positive relationship was found between congruent (i.e., perceived as androgynous and having communal and agentic traits) managers and perceived authenticity. These findings support previous research that emphasized that the traditional management roles of men and women were less relevant today. Kark (2004) underlined this point when she presented an alternative view of traditional management styles as less effective. Furthermore, effective leadership can no longer be defined in male terms, but should combine male and female styles that add flexibility and an advantage to both genders in management roles (Kark et al., 2012).

Like previous research, the present study found that women managers that are perceived as androgynous are also perceived as able to integrate and cope with the double paradox: contrasting expectations that women should adopt “agentic” behaviors (assertiveness, competitiveness, etc.) to fulfill their management role properly, but at the same time act “communally” to realize their gender role. Additionally, these women are also perceived by their subordinates as more authentic leaders. Research on the topic explained that when women behave in a way that contradicts their gender role, it can be interpreted as inauthentic and “by script”. Therefore, the awareness and sincerity exhibited by the manager and the degree to which she is perceived as authentic are crucial (Kawakami et al., 2000). Thus, women managers that are perceived by their subordinates as employing an androgynous gender role identity and combined “agentic” and “communal” management styles are seen as more authentic managers than others.

Examination of the second hypothesis revealed a positive relationship between the degree of perceived authenticity and leader-member exchange (LMX). These findings are compatible with previous studies. In this context, Avolio and Gardner (2005) claimed that authentic leadership/management could create positive LMX between managers and subordinates. Also, since authentic leaders are more willing to share information and to express their inner thoughts and feelings, they generate more trust, loyalty, and identification (Wang, Law, Hackett, & Chen, 2005). The present study has shown that their apparent integrity and sincerity helped the managers to create long-term mutual relationships with their subordinates, to the point that they were perceived as partners and sharing expectations and goals, which is the essence of authentic management.

The third and fourth hypotheses indicated a positive relationship between the congruence of gender role identity (androgynous/non-androgynous) – combined management styles (agentic + communal) and the quality of LMX, in the managers’ and the subordinates’ eyes.

The fifth hypothesis examined the type and quality of this relationship by assuming the involvement of “authentic management” as a moderator, and this link was corroborated. These findings correspond with previous studies, and answer the main research question: can the “winning combination” serve as a single solution for women managers? Studies have shown that women managers that are perceived as authentic and can combine management styles are able to avoid the paradox concerning conflicting expectations. It was found that, in the view of men, women who are “male” in style but aware are considered more successful managers than women who adopted a male style but were neither aware nor sincere (Kawakami et al., 2000). Surprisingly, this view is common among women too, even more so than among men, particularly when it concerns women in senior management positions (Rosette & Tost, 2010).

Beyond the study's hypotheses, a gap was found between managers’ and subordinates’ reports regarding LMX. When there was no congruence between gender role identity and gender management characteristics, there was a gap between the reported LMX of managers (who reported them as higher) and their subordinates. On the other hand, if there was congruence, no significant differences are found between the reported LMX of managers and their subordinates. These findings are in line with previous research, which submitted the premise that traditional management styles are less effective, whereas androgyny and combined management styles contribute to LMX (Kark et al., 2012).

Authentic management can provide an additional explanation for the abovementioned link. Authenticity is all about awareness and sincerity. An authentic manager must see different sides, adapt to various situations, and fulfill various roles. However, it must come from her personality and not be perceived as faking or role-playing (Goffee & Jones, 2005). It is not enough for women managers to be aware of their own and their subordinates’ values; they must believe that they serve their community. Moreover, their image as a leader must reflect their common values and ideas in order to gain their subordinates’ legitimization (Eagly, 2005). Thus, a manager that just plays a role and is unaware of her true relationship with her subordinates would probably score her LMX as higher, due to the very unawareness that clouds her ability to see the “fakery” perceived by her subordinates.

ConclusionsThe findings of the present study lead us to a number of conclusions.The current debate regarding the question “Who is a good manager?” has expanded and become more complex by asking “Who is a good female manger?” The attempt to steer clear of the traditional dichotomy and to choose integration and androgyny seems to indicate that it is not enough to combine management styles, and certainly not to call it a “winning combination”. The reason is that even when managers combine styles, women still pay a higher price. The well-known asymmetry and dichotomy have changed, but still exist. This study has examined only women and can therefore lead to a more focused conclusion, because when women evaluate other women, the perceived quality of their relationship depends on the combination. Nevertheless, the number of managers in this study that were perceived by their women subordinates as exhibiting congruence was significantly lower than those that were perceived dichotomously as either “male” or “female”. Specifically, they indicated the connection, but something was still missing. Authenticity filled that void. The added value was obtained when the variable “authenticity” was added and moderated the relationship. Women managers that adopt an authentic management style may find it easier to deal with combined styles and androgyny, and make the best of them. What is more, the combination of authenticity and congruence indicated LMX based on trust, mutuality, combined emotions and rationale, and determination to achieve “natural management” that we all long for, regardless of sex or gender. Women managers that exhibit congruence but do not act authentically create a leader-member exchange that is perceived as fake and unstable. I believe that this situation could duplicate what happened when women entered the corporate world and adopted extreme male characteristics, which prevented them from climbing the corporate ladder because they were disliked and perceived as “playing a role”, rather than acting with integrity and inner truth. Thus, authenticity can serve as a solution for both women and men because it concerns the management world regardless of gender. Nevertheless, women's road is still longer and more challenging, albeit possible.

Limitations- •

The participants were asked to fill out a long 6-part questionnaire. It is possible that some did not take it seriously and marked random answers in order to complete it quickly. This might affect the results.

- •

The study was conducted at one point in time. A longitudinal study might have supplied deeper insights.

- •

Most of the questionnaire was composed of closed questions, which could have limited the respondents’ freedom to supply answers that were a more accurate reflection of their view, especially as the questions concerned subjective measures.

- •

All of the research variables were measured by the same tool and at the same time. This could have created serial responses, i.e., the tendency to answer all of the items in a similar manner. The source of this bias is the respondent's desire to portray herself in a consistent way.

- •

The size of the sample was relatively small (120 pairs, because the LMX questionnaire was filled out simultaneously by managers and subordinates). It is possible that a larger sample, particularly of managers, would have provided a more varied sample and a higher level of significance, which in turn would have produced different results.

- •

The questionnaires were handed out to subordinates and managers. It is possible that knowing this could have affected the replies. Although the questionnaires were anonymous, placed in envelopes, and then in a closed box, many respondents had doubts and asked what the code was for.

- •

Managers usually filled out more than one questionnaire (according to the number of subordinates). This may have created a bias, specifically that the information regarding each subordinate could have served as a reference point for the next one.

- •

In some cases the questionnaires were distributed in organizations that I am involved with (as a consultant), which may have caused some subordinates to feel insecure, because they knew that I had a client/service-provider relationship with their manager. Consequently, I tried to use other consultants as much as possible.

- •

This study did not focus on the managers’ management level, which could possibly affect their degree of congruence, and the awareness and authenticity required at higher levels. One could assume that in senior management positions, which are traditionally identified with men, women's incongruence would be more pronounced (Kark et al., 2012). In this context, it would therefore be interesting to examine whether authenticity would serve as a solution for senior women managers. Furthermore, it could be possible to compare the evaluations of subordinates managed by women in junior positions with those of subordinates managed by women in senior positions.

- •

Investigation could be expanded to include the differences between men and women managers. Do androgyny and combined management characteristics serve men and women equally? Do they receive the same validation, or do women managers pay a higher price? Recent studies (Kark et al., 2012) have dealt with this question, but have not considered authenticity. It would be interesting to observe whether authenticity affects the price paid by women versus men, and whether it serves as a solution in this case as well.

- •

The present study focused on women subordinates managed by women. The different perceptions of male and female subordinates would be of interest. Additionally, other variables such as perception of women managers as effective, sympathetic, imaginative, etc. could be added.

- •

It might be interesting to examine various other work sectors and compare them; for instance, sectors that are considered “female” such as education, in which more women hold senior positions than in other “male” sectors. The present study did include women managers from a number of sectors, but due to the size of the sample, no significant comparisons could be made.

The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.