The recruitment process aims to request relevant information from applicants, but sometimes this could be used to discriminate. Based mainly on the legal framework and the Rational Bias, the present paper explores the use of potentially discriminatory content against women in Spanish companies according to the enforcement of the equal employment opportunity legislation in 2007, and its relationship with organizational results. We have performed a comparative study between 2005 and 2009 implementing a combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis. All the websites of the Spanish Stock Exchange were analyzed. Results show that companies did include potentially discriminatory questions in application forms, even after the law enforcement, but not in recruitment statements. Regarding organizational results, small but significant relationships between legal fulfillment and annual returns were found, but these results could have been influenced by factors attributable to the economic crisis. To conclude, we provide recommendations regarding desirable policies and organizational practices in the context of the area being studied.

El proceso de reclutamiento es una fase importante del proceso de selección, donde se solicita información personal de los candidatos. Pero esta información podría ser utilizada de forma discriminatoria en la toma de decisiones. Basándonos en la Teoría del Sesgo Racional y en la legislación vigente en materia de igualdad, en este estudio se explora el posible uso discriminatorio contra las mujeres en las empresas que cotizan en la bolsa española, así como su relación con los resultados organizacionales. Hemos realizado un estudio comparativo entre los años 2005 y 2009 del contenido de las hojas de solicitud de empleo en las webs de todas las empresas que cotizaban en bolsa en esos años. Combinando técnicas cualitativas y cuantitativas, los resultados mostraron que las empresas incluían contenido potencialmente discriminatorio tanto antes como después de la Ley de Igualdad entre Mujeres y Hombres de 2007. Asimismo, hemos encontrado relación entre los resultados anuales de las empresas y el cumplimiento estricto de la legislación. Finalmente, incluimos recomendaciones de buenas prácticas para la política organizacional durante el reclutamiento.

Recruitment is the first step of personnel selection and can be defined as the process of attracting competent individuals to fill jobs (Schmitt & Chan, 1998). Specifically, Stone, Lukaszewski, Stone-Romero, and Johnson (2013) noted that the purpose of recruitment is “to provide the organization with a large pool of job applicants who are well suited for existing openings in terms of their knowledge, skills, abilities, and other attributes” (p. 51). After recruitment, the selection process takes place, and decision makers evaluate the capabilities of applicants on the attributes required to fill the job effectively (Smith & Robertson, 1993). But, during recruitment, applicants provide personal information that companies use to make hiring decisions, and sometimes the information requested by companies is inappropriate and could be used to discriminate (Bell, Ryan, & Wiechmann, 2004). Countries such as the USA and the UK have developed legal dispositions to ensure equality in the selection process (Aguinis, 2009). According to Myors et al. (2008), the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in USA derived in a legal environment which had an important effect on I/O psychology. In this way, employers have become more aware of the importance of legal issues during personnel selection procedures. As a result, practices as job analysis, criteria development, tests development and validation have been analyzed and improved. In the case of UK, the legal environment for selection made employers to be systematic and to conduct a job analysis when they are looking for employees. In the case of Spain, the legislation for minority groups during selection is weak despite having equal opportunities legislation in force. Consequently, Spain has yet to study and integrate its impact in current recruitment practices (García-Izquierdo, Aguinis, & Ramos-Villagrasa, 2010).

Following Pager and Western (2012), one of the main problems of studying equality at the workplace is that contemporary forms of discrimination are hard to investigate in a direct way. In other words, decision-makers who discriminate against a focus group or individual members are unable to admit the discriminatory elements which directly affect their decisions. Therefore, in the present paper we are going to analyze secondary data. We cannot ask directly an organization if they have discriminatory elements inside the organization because the answer will be a clear no; however we can analyze if there are discriminatory elements in the recruitment process (e.g., the recruitment sections in the companies’ websites) using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. When we detect potentially discriminatory content, as for example in the recruitment section of a company website, it signifies that the potential for discrimination exists (Stone-Romero & Stone, 2005). Furthermore, even without the latter discriminatory intent, the use of inadequate content generates negative reactions in applicants, which weaken the personnel selection process (e.g., Bauer et al., 2006; Truxillo, Steiner, & Gilliland, 2004).

The study reported here is built on a previous one (i.e., García-Izquierdo et al., 2010) that we developed with two purposes: (1) as a preliminary approximation to the Spanish practices in e-recruitment and (2) to show that a science-practice gap (Cascio & Aguinis, 2008) exists also in this context. Now, we want to take a step forward with a deeper study focused on the analysis of the relationship between legislation, real recruitment practices, and its impact on organizational results. Thus, taking the European legal framework and the literature regarding discrimination in job access into account, the current study aims to explore the use of potentially discriminatory content in the websites of listed companies in Spain. Specifically, we want to measure the degree of improvement in recruitment practices present in these websites in compliance with adoption of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act (Ley Orgánica de Igualdad de Oportunidades entre Mujeres y Hombres, LOIMH) in 2007. Furthermore, we wish to investigate whether the e-recruitment practices regarding gender discrimination have any relationship with organizational results. The findings reported here will be useful for Spanish researchers and practitioners, who need to ensure the equality of their selection procedures. Additionally they will also serve as guidance to those countries whose equal-opportunity legislation is being developed and, of course, to best-practice recruitment specialists.

Internet Recruitment and BiodataNowadays, the development of new technologies has turned the Internet into the prevalent recruitment source (Pfieffelmann, Wagner, & Libkuman, 2010). For example in Spain, according to the Observatorio Nacional de las Telecomunicaciones y la Sociedad de la Información(ONTSI, 2015) [the Spanish Observatory for Telecommunications and the Information Society] during 2014, 75.8% of companies with Internet access had their own website and 21.1% of companies used it to advertize the jobs or receive work requests. This means an increase of 18.3% and 3.4% respectively from 2008, which is the first year with available data on this issue. This new form of recruitment, named e-recruitment, implies important changes with regard to the traditional recruitment. According to Cober, Brown, Keeping, and Levy (2004), the differences are detectable when we refer to the experiences which become available with Internet web pages (e.g., images, sound, animations) as well as the possibility of providing a dynamic experience where the job-seeker is involved in the recruitment process instead of being a passive informational receiver. Moreover, e-recruitment offers many practical benefits in comparison with traditional methods such as the use of companies’ own corporate websites as a source of recruitment (Lievens & Harris, 2003), which serve to attract future workers through web content (Cober, Brown, Blumenthal, & Levy, 2001) and appearance (Thompson, Braddy, & Wuensch, 2008), and which can result in substantial savings in terms of financial costs and time invested (Sylva & Mol, 2009). Although e-recruitment offers many possibilities, it has several limitations. To start with, there are more applicants which can prove detrimental to the quality of the e-recruitment process (Boehle, 2000), and some potential applicants may become excluded due to demographic differences in Internet access (McManus & Ferguson, 2003).

During the recruitment process, organizations begin to obtain biographical data (biodata) from candidates. Biodata measures come from standardized methods of measuring past behaviors (e.g., education, job experience) that are relevant to future job performance (Becton, Mathews, Hartley, & Whitaker, 2009). The use of biodata has certain advantages such as their low collection cost and acceptable predictive validity (between .30 and .40) across a wide range of criteria and situations (Allworth & Hesketh, 2000). In addition, applicants do not usually fake their answers (Schmitt & Kunce, 2002). However, biodata cannot be considered trouble-free: biodata are perceived as somewhat lacking in terms of their legality (Furnham, 2008) and recent research has shown that it entails a much higher adverse impact than was previously supposed (Bobko & Roth, 2013). Nowadays, the concerns related with legal compliance and discrimination in the use of biodata are actually very relevant issues for organizations. For instance, the inclusion of content suggesting a preference for a specific gender which is unrelated to job performance could be a first step towards discrimination (Stone-Romero & Stone, 2005). Similarly, the inclusion of inappropriate or invasive content could promote the self-exclusion of potentially valuable applicants (Truxillo et al., 2004) and generating negative reactions from applicants (Bauer et al., 2006).

Discrimination in e-RecruitmentFollowing Guion (2011), the information gathered during recruitment should be job-related in accordance with a prior job analysis. In consequence, any question unrelated with the job content could be considered as invasive and may be conducive to the generation of negative reactions and perceptions of unfairness in applicants (Stone-Romero, Stone, & Hyatt, 2003). This is because it bestows upon decision makers the ability to make discriminatory choices (Stone-Romero & Stone, 2005).

Given its negative consequences, one expects that companies will not include invasive content in their selection processes. Surprisingly however, empirical evidence exists which indicates that public (Wallace, Tye, & Vodanovich, 2000) and private (García-Izquierdo et al., 2010) companies use potentially discriminatory items in e-recruitment. This could be explained by the Rational Bias Theory (Larwood, Gutek, & Gattiker, 1984). Rational Bias Theory has shown that employees might discriminate if they believe that both their supervisors and the organizational climate promote discrimination (e.g., Larwood, Szwajkowski, & Rose, 1988; Powell & Butterfield, 1994; Szwajkowski & Larwood, 1991), and this even in the absence of their own prejudices (Trentham & Larwood, 1998). According to Trentham and Larwood (1998) the Rational Bias Theory includes two preconditions which serve to produce gender discrimination: the preference norm and the compliance instrumentality. On the one hand, the preference norm refers to the perception of decision makers that other significant parties (mainly supervisors, but also clients) expect gender-discriminative choices from them. On the other hand, compliance instrumentality suggests that decision makers feel that their own careers could be affected if they do not support the existing bias. Although the authorship of the recruitment content is usually unknown, there is a broad agreement that executives are the persons involved in their preparation (Barr, Stimpert, & Huff, 1992). Consequently, and in accordance with the Rational Bias Theory explained above, the presence of potentially discriminatory content promotes discrimination. That is, if cues of discrimination are found in the e-recruitment sections it could signify that discrimination is expected by the managers of the organization according to the preference norm. In order to study in-depth what we could consider as discrimination, the legal framework must be taken into account.

The Legal Framework regarding Gender Equality and its FulfillmentSince its inception, the European Union has protected equality in the workplace, developing extensive legislation to prevent discrimination between women and men (García-Izquierdo & Ramos-Villagrasa, 2012). This equal-opportunity legislation commenced in the seventies with the enactment of some relevant Directives such as the Council Directives 75/117/EC and 76/207/EEC regarding equal pay, equal treatment in employment, and vocational training. At the beginning of the present century there was a renewed attempt to deal with this matter with the Council Directive 2000/78/EC to prevent all types of discrimination (gender, age, etc.). Some years later, the Council Directive 76/207/EEC gave member states an active role in achieving the objective of equality between men and women for example when formulating and implementing laws, and the Council Directive 2004/113/EC implemented the principle of equal treatment between men and women in the access to and supply of goods and services. More recently a new Directive has been provided, the EU Directive 2006/54/EC, which contains what we could consider as discrimination.

According to the EU Directive 2006/54/EC, discrimination can be performed directly if one person is treated less favorably on grounds of gender, or indirectly if an apparently neutral provision, criterion, or practice would put persons of one gender at a particular disadvantage compared with persons of the opposite gender. It should be noted that indirect discrimination alone is only acceptable based on the three following assumptions: (a) for professional activities where gender is a factor because of the nature or conditions of the activity to be performed, (b) to protect women, particularly in pregnancy and childbirth, and (c) to promote equal opportunities between men and women (art. 2.6 EU Directive 76/207 on Equal Treatment).

All in all, these Directives 2002/73/EC, 2004/113/EC and 2006/54/EC admonished member states to incorporate their content into countries’ respective legal systems between 2005 and 2008. Spain for example developed its own legislation in 2007 by implementing the Organic Act 3/2007, relating to the effective equality between women and men (LOIMH). In accordance with García-Izquierdo and García-Izquierdo (2007), art.5 of the LOIMH establishes that information gathered during personnel selection must focus on data related with job performance and must seek to avoid unrelated and invasive information as well as unfair procedures or unequal decisions. However, one of the major concerns of the LOIMH is what one understands to be discriminatory content, at least in absence of jurisprudence. In line with legislation, discrimination is only acceptable when dealing with professional activities where gender is a factor because of the nature or conditions of the activity to be performed. Consequently, we may consider that the inclusion in e-recruitment sections of any gender-related content which fails to justify a clear job-description (role) is potentially a discriminatory practice.

Equally important, as a well-built legal framework, is the impact of the legal dispositions on real practices, given that the true drivers of change are the practitioners, not the policies themselves (Yanow, 1999). This places the focus on the legal fulfillment. Research has shown that legal dispositions need some time to produce changes (e.g., Jain, Lawler, Bai, & Lee, 2010; Weichselbaumer & Winter-Ebmer, 2007). However, the time needed remains unclear. In fact, the number of articles addressing this problem is very scarce. Weichselbaumer and Winter-Ebmer (2007) performed a meta-analytic study regarding the gender-wage gap in 62 countries and found a small but positive effect during the first three years after the passing of the legislation. In a wider perspective, Jain et al. (2010) investigated a set of equal employment opportunity indicators in Canada during seven years, finding an upward trend over time. These studies show that it take at least a year to see changes in the practices of organizations.

The Present StudyThe present study focuses on searching for potentially discriminatory content against women in the websites of listed companies on the Spanish Stock Exchange. As we stated before, we developed a preliminary investigation regarding this question in the past (García-Izquierdo et al., 2010). In that study, we found that companies did not change their practices according to law enforcement. However, we want to complete our approach to Spanish e-recruitment by: (1) focusing on gender equality, because Spanish legislation includes specific guidelines in that sense; (2) developing and testing hypotheses based on the aforementioned arguments; (3) increasing our scope of the e-recruitment practices, including recruitment statements; and (4) analyzing the impact of the Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) law fulfillment in terms of its impact on organizational results. Therefore, we reach a better perspective of the Spanish e-recruitment.

Since the LOIMH has been in force from 2007, it is easy to be expected that companies would follow legal dispositions, but empirical studies have shown discrimination cues after the law enforcement (Alonso, Táuriz, & Choragwicka, 2009; García-Izquierdo et al., 2010; Mateos, Gimeno, & Escot, 2011). Therefore, here we offer an analysis of changes in the practices implemented by companies in Spain as a result of the introduction of LOIMH. If some improvement indicators are identified, then we can expect a progressive trend over time (e.g., Jain et al., 2010; Weichselbaumer & Winter-Ebmer, 2007), but if no changes appear to exist, then some kind of intervention is recommended (e.g., developing specific guidelines). Moreover, potentially discriminatory content could be detected when asking questions regarding gender, but also regarding marital status and children, as women are stereotyped for taking care of their family, especially when children are involved (e.g., Bobbit-Zeher, 2011; López-Zafra & García-Retamero, 2011; Sarrió, Barberá, Ramos, & Candela, 2002). In relation to the foregoing ideas, we believe that content regarding gender, marital status, or children could potentially be considered as discriminatory against women.

An important and closely related issue is the timespan of the study. The transposition of European Council directives by member states should have been finished between 2005 and 2008. Given that in 2005 the Spanish Government had not even published any draft legislation, we decided to commence our data gathering by aiming to capture “pre” enforcement practices in e-recruitment. Additionally, as Amor (2010) states, since 2005 Spain has moved from a period of economic growth to a recession and higher unemployment rates, the latter have been more pronounced for women. Job scarcity and concerns regarding unemployment have converted obtaining a job in one of the most desired objectives of the Spanish population, making equality considerations in personnel selection even more important. With respect to “post” condition measures, the LOIMH was finally enforced in 2007. Given that prior research has shown that legal dispositions require between one and three years to produce an observable impact (e.g., Jain et al., 2010; Weichselbaumer & Winter-Ebmer, 2007), we decided to gather data two years before and after the LOIMH enforcement (i.e., 2005 and 2009).

As stated previously, nowadays discrimination is subtler than in the past (Pager & Western, 2012). Thus, we require indirect methods for investigating discrimination. In this study, we have relied on narrative policy analysis, which helps to conciliate the policy narrative and the counter narrative (i.e., opposed position, in our case company practices) by comparison of both the former and the latter in order to generate a metanarrative acceptable to both sides (Hampton, 2004). From our point of view, this metanarrative should demonstrate that compliance with legal dispositions can in fact produce better organizational results than discriminative practices.

Regarding organizational results, Huselid (1995) stated that Human Resources practices contributed to the profitability of organizations. Generally speaking, research shows a weak but existing relationship (Wright & Gardner, 2003). This is because Human Resources practices are a somewhat remote indicator of results which are additionally affected by a pool of other different variables (Paauwe, 2009). In recent years, some authors have explored the relationship between equality practices and organizational results (e.g., Armstrong et al., 2010; Bloom, Kretschmer, & Van Reenen, 2011; Lee & DeVoe, 2012). However, to the best of our knowledge nobody has actually analyzed prior to this study the impact of e-recruitment discrimination or equality practices on organizational results, in Spain or elsewhere.

Based on our review of the literature in connection with the legal dispositions regarding equality at work, the e-recruitment in personnel selection, and their impact on organizational results, we propose the three following hypotheses. First of all, in accordance with the foregoing, if companies fulfill the LOIMH, one expects that they will only include job-related content, otherwise, the inclusion of potentially discriminatory content could be seen as a preference norm (Rational Bias Theory; Trentham & Larwood, 1998), serving to promote discrimination to job entry (Stone-Romero & Stone, 2005). Given that prior research in Spain has shown discrimination cues in the selection process (Alonso et al., 2009; García-Izquierdo et al., 2010; Mateos et al., 2011), we expect to find potentially discriminatory content in e-recruitment.

H1: Companies’ websites include potentially discriminatory content in their e-recruitment sections.

Secondly, and according with this idea, our study mentioned above shows that at the category level there is no change over time in the application forms (e.g., the number of companies asking for gender remains stable). However, research has shown an improvement in equality practices after the enactment of the law (e.g., Jain et al., 2010; Weichselbaumer & Winter-Ebmer, 2007). Given that Spanish EEO law is focused on gender, we expect that some positive changes could be seen when gender-content is analyzed as a whole.

H2: There is significant improvement in e-recruitment practices regarding gender equality (i.e., a reduction of potentially discriminatory content) before the LOIMH and after its enforcement.

Lastly, given that previous studies have shown a positive relationship between equality practices and organizational results (Armstrong et al., 2010, Bloom et al., 2011; Lee & DeVoe, 2012), we expect to find that companies with better equality practices (i.e., less potentially discriminatory content in e-recruitment) tend to obtain better organizational results than other companies.

H3: A negative association exists between the potentially discriminatory content of websites and the organizational outcomes of the companies.

MethodSampleThe sample is composed by all the companies listed on the Spanish Stock Exchange (i.e., Bolsa de Madrid). These companies fulfill two essential conditions for our study: (1) they had demonstrated their economic success in the past and (2) they are large, well-known, and influential. Given their social relevance we have assumed that these companies can obtain some benefits from a high degree of legal compliance because, as Cropanzano and Greenberg (1997) noted, adopting EEO practices improves organization's image. Furthermore, these companies have to comply with the legislation, and in consequence can be expected to have made changes in their e-recruitment pursuant to the LOIMH enforcement.

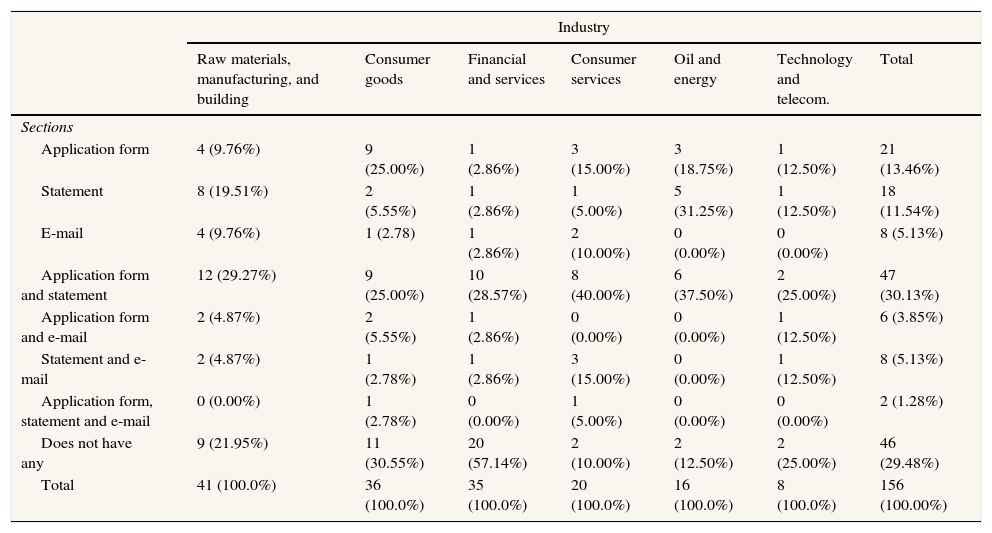

In 2005, 181 companies were listed on the Spanish Stock Exchange. Thirty of these companies formed part of consortiums that shared web access on a website common to all members, and thus they could be considered as the same company in our analysis. Therefore our sample is composed of 156 websites. In Table 1 we classified these companies in accordance with two criteria: firstly, the type of recruitment sections in their website (application forms, recruitment statements, e-mail, or several of these options at the same time), and secondly, the type of industry. The effective sample size was made of companies with recruitment statement, n=75, and with application forms, n=76. As we can see in Table 1, most companies included both recruitment statement and application forms (n=47, 30.13%). The number of organizations without options for e-recruitment in their websites was practically identical (n=46, 29.48%). It is also worth highlighting that 8 companies (5.13%) offered the possibility of sending the résumé by e-mail, and only 2 companies (1.28%) included recruitment statements, an application form, and e-mail address.

Number of companies classified by industry and website sections.

| Industry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw materials, manufacturing, and building | Consumer goods | Financial and services | Consumer services | Oil and energy | Technology and telecom. | Total | |

| Sections | |||||||

| Application form | 4 (9.76%) | 9 (25.00%) | 1 (2.86%) | 3 (15.00%) | 3 (18.75%) | 1 (12.50%) | 21 (13.46%) |

| Statement | 8 (19.51%) | 2 (5.55%) | 1 (2.86%) | 1 (5.00%) | 5 (31.25%) | 1 (12.50%) | 18 (11.54%) |

| 4 (9.76%) | 1 (2.78) | 1 (2.86%) | 2 (10.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 8 (5.13%) | |

| Application form and statement | 12 (29.27%) | 9 (25.00%) | 10 (28.57%) | 8 (40.00%) | 6 (37.50%) | 2 (25.00%) | 47 (30.13%) |

| Application form and e-mail | 2 (4.87%) | 2 (5.55%) | 1 (2.86%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (12.50%) | 6 (3.85%) |

| Statement and e-mail | 2 (4.87%) | 1 (2.78%) | 1 (2.86%) | 3 (15.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (12.50%) | 8 (5.13%) |

| Application form, statement and e-mail | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (2.78%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (5.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (1.28%) |

| Does not have any | 9 (21.95%) | 11 (30.55%) | 20 (57.14%) | 2 (10.00%) | 2 (12.50%) | 2 (25.00%) | 46 (29.48%) |

| Total | 41 (100.0%) | 36 (100.0%) | 35 (100.0%) | 20 (100.0%) | 16 (100.0%) | 8 (100.0%) | 156 (100.00%) |

Note. N=156. Description of industries: (1) raw materials, manufacturing and building: companies related with production or manufacturing of unprocessed material of any kind, and building construction; (2) consumer goods: companies that produce processed products to the final customer; (3) financial services and real estate: companies that provide services related with money management (e.g. banks, investment funds) and the renting/selling of buildings; (4) consumer services: companies that render services to the final customer; (5) oil and energy: companies that obtain, process, and sell fuel and/or energy; (6) technology and telecommunications: companies that product goods and render services related with information technology (e.g., computers, cell phones).

If we analyze the different options as regards different industries, we observe that more than half of the companies from financial services and real estate do not offer any recruitment option (n=20, 57.14%). Something similar occurs with consumer goods companies, where almost one third of the companies in the industry (n=11, 30.55%) do not have any e-recruitment section. There is a lot of heterogeneity in other industries, but a number of companies combine recruitment statements and application forms (n=47, 30.13%).

VariablesWe take into account three variables in our study: (1) potentially discriminatory content of websites, (2) improvement of e-recruitment practices in accordance with LOIMH enforcement, and (3) organizational results.

Potentially discriminatory content. Following the recommendations of Duriau, Reger, and Pfarrer (2007), potentially discriminatory content (PDC) was measured by the recount of clear proxies of discrimination, that is, presence of items related with gender discrimination in application forms of every company, using a single variable for each year (2005 and 2007). As we explained before, we consider PDC all those items related with gender, marital status, and number of children. We also consider that content about military service is a question about gender, because in Spain it was mandatory for men until year 2001. Once the PDC variable was made, we analyzed its normality by conducting skewness and kurtosis analyses. Given that results suggest that these variables do not follow a normal distribution (PDC2005 skewness=-.60, SE=.30, kurtosis=−1.12, SE=0.58; PDC2009 skewness=.11, SE=.30, kurtosis=−1.02, SE=0.58), we use nonparametric tests in the quantitative analysis.

Improvement on e-recruitment practices. Changes in gender discrimination were measured subtracting the value of the PDC variable for 2005 from the PDC variable for 2009. Thus, positive values are related with improvement and negative values with worse e-recruitment practices (i.e., an increase in the potentially discriminatory content).

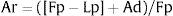

Organizational results. This variable was operationalized by the annual returns of each company. Annual return was calculated every year as follows:

where Ar is the annual return, Fp is the stock price on the first trading day, Lp is the closing price on the last trading day, and finally, Ad is the accumulative dividend obtained during the year. The higher values indicate better results.Procedure and AnalysisBuilding on previous steps made in narrative policy analysis such as those of McBeth, Shanahan, Arnell, and Hathaway (2007) and Shanahan, McBeth, Hathaway, and Arnell (2008), our approach merges qualitative and quantitative analysis of the recruitment sections obtained from the websites of listed Spanish companies. Data were collected from the official websites in two waves, the first in 2005 (two years before the LOIMH) and the second in 2009 (two years after the LOIMH). In the first wave we captured all the text content from the website recruitment statements and from the application forms. In the second wave (2009) we recorded application forms and the annual returns of the companies between 2005 and 2009. Recruitment statements were not recorded in 2009 because the results of 2005 showed us that their content were irrelevant for the purposes of our research.

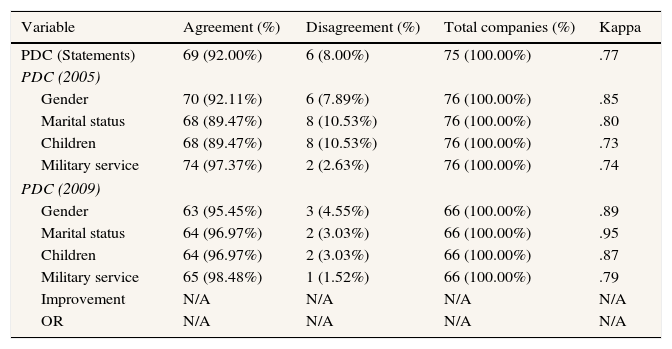

After data collection we proceeded with the qualitative approach. This was performed using content analysis, taking the content of the websites (i.e., recruitment statements and applicant forms) as the unit of analysis. The content analysis was conducted by two trained coders. We used different analyses for contents and for application forms. With the contents we took advantage of NVIVO 2.0 software in order to analyze the appearance of the illegal variables and the context in which they appear, while the analysis of the application forms consisted of the categories revision, considered as proxies of potentially discriminatory content and a recount of how many companies used each category. The degree of uniformity between coders was estimated by the Kappa-index which is shown in Table 2. As we can observe from the latter, the indices of agreement are between K=.73 and K=.95, that is, between “substantial agreement” and “almost perfect agreement” (Landis & Koch, 1977). Finally, the researchers discussed their disagreements with the authors and this process led to the final classification with a great agreement (K=.98).

Intercoder reliability.

| Variable | Agreement (%) | Disagreement (%) | Total companies (%) | Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDC (Statements) | 69 (92.00%) | 6 (8.00%) | 75 (100.00%) | .77 |

| PDC (2005) | ||||

| Gender | 70 (92.11%) | 6 (7.89%) | 76 (100.00%) | .85 |

| Marital status | 68 (89.47%) | 8 (10.53%) | 76 (100.00%) | .80 |

| Children | 68 (89.47%) | 8 (10.53%) | 76 (100.00%) | .73 |

| Military service | 74 (97.37%) | 2 (2.63%) | 76 (100.00%) | .74 |

| PDC (2009) | ||||

| Gender | 63 (95.45%) | 3 (4.55%) | 66 (100.00%) | .89 |

| Marital status | 64 (96.97%) | 2 (3.03%) | 66 (100.00%) | .95 |

| Children | 64 (96.97%) | 2 (3.03%) | 66 (100.00%) | .87 |

| Military service | 65 (98.48%) | 1 (1.52%) | 66 (100.00%) | .79 |

| Improvement | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| OR | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Note. PDC=potentially discriminatory content; Improvement=improvement of e-recruitment practices; OR=organizational results. Data from gender, marital status, children, and military service proxies refers to application forms.

The next step after content analysis was the empirical analysis. As the PDC variables do not follow a normal distribution, we use a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to determine if changes in potentially discriminatory content existed in e-recruitment practices pre and post the LOIMH, and Spearman correlations to investigate the relationship between the variables, including the organizational results.

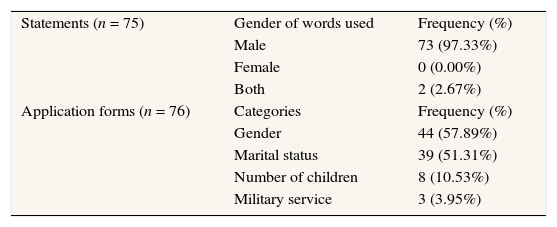

ResultsPreliminary AnalysesTable 3 provides an overview of the potentially discriminatory content in the e-recruitment sections of companies’ websites in 2005 before the LOIMH was in force. This initial screening showed that gender equality is scarcely considered in statements (n=2, 2.67%) and, on the contrary, potentially discriminatory content regarding gender is quite common in the application forms (gender: n=44, 57.89%; marital status: n=39, 51.31%; number of children: n=8, 10.53%; and military service: n=3, 3.95%) (for further details of the content in the e-recruitment sections of companies’ websites, see García-Izquierdo et al., 2010).

Potentially discriminatory content in the e-recruitment sections of companies’ websites in 2005.

| Statements (n = 75) | Gender of words used | Frequency (%) |

| Male | 73 (97.33%) | |

| Female | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Both | 2 (2.67%) | |

| Application forms (n = 76) | Categories | Frequency (%) |

| Gender | 44 (57.89%) | |

| Marital status | 39 (51.31%) | |

| Number of children | 8 (10.53%) | |

| Military service | 3 (3.95%) |

Recruitment statements and application forms were analyzed separately. In relation to recruitment statements, all of them (n=75) showed a clear structure: (1) data related to the company, (2) whom the statement is directed, (3) and equality and work life balance, but this last section is only shown in a few companies (n=3, 4.00%). The gender treatment was another interesting feature because the absolute majority of recruitment statements (n=73, 97.33%) refer to their workers, collaborators, and employees using the male grammatical gender. However, it should be pointed out that the plural male gender in Spanish includes both males and females, although this usage as such is somewhat controversial. Only two recruitment statements (2.67%) contemplated both genders, but it is important to point out that in one of these websites the female gender appears first, which seems to indicate that in this case the majority of workers of this company were women. In the other case, both genders were used only in some parts of the text.

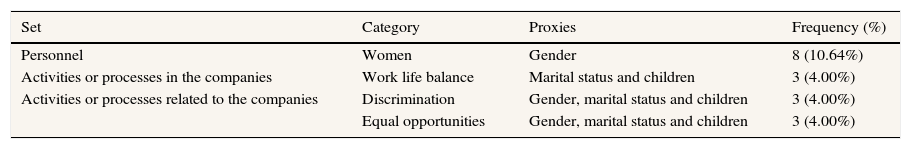

With reference to the content, we have four sets of categories object of this study: (1) personnel, which includes: professional, team, people, employees/workers, co-workers/participants, human resources, personnel; staff; women, young; (2) personal characteristics required, which includes initiative, responsibility, health, motivation, effort, security, talent, employment, abilities/competencies/skills, engagement, leadership, personal development, learning, creativity, honesty, geographical mobility, open mind, loyalty, discretion, and security; (3) activities or processes in the companies, including work, training, professional development, professional career, promotion, driving force, social advantages, transparency, work, and home-life reconciliation; and (4) activities or processes related to the companies, composed by work, enterprise, organization, company, management, job, values, aims, projects, quality, culture, strategy, view, innovation, principles, incorporation, challenge, human resource management, excellence, employee retention, share capital, human capital, flexibility, efficiency, quality of life, human resources policy, integrity, mission, joining, attraction, mobility, philosophy, risk prevention, ethics, professional profile, discrimination, recruitment, equal opportunities, and disability. In the application forms (n=76), we classify the items in three sets in accordance with their content: (a) personal data, (b) availability, and (c) other data. In Table 4 we present the categories found in the application forms classified according with three sets of data.Hypothesis 1 Potentially Discriminatory Content in e-Recruitment Sections

Categories in statements (2005).

| Set | Category | Proxies | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel | Women | Gender | 8 (10.64%) |

| Activities or processes in the companies | Work life balance | Marital status and children | 3 (4.00%) |

| Activities or processes related to the companies | Discrimination | Gender, marital status and children | 3 (4.00%) |

| Equal opportunities | Gender, marital status and children | 3 (4.00%) |

N = 75.

Our first hypothesis proposed that companies’ websites included potentially discriminatory content (comments involving gender, marital status, number of children, and military service) in their recruitment sections. After analyzing recruitment statements (n=75), we found that some of them could be related with gender discrimination in a direct or indirect way. These categories were “women” (n=8, 10.64%) from the personnel set, “reconciliation of work and home-life” (n=3, 4.00%) from the activities or processes in the companies set, and “discrimination” (n=3, 4.00%) and “equal opportunities” (n=3, 4.00%) from the activities or processes related to the companies’ set. Although we find categories that could be related with gender discrimination, the context in which they were used does not necessarily signify a discriminatory intention. After that, we did not consider appropriate to analyze the recruitment statements for 2009 (for further detail, see García-Izquierdo et al., 2010).

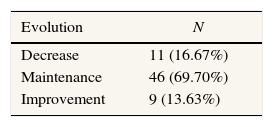

Talking about application forms, some companies have not been evaluated in both years (2005 and 2009) due to mergers and acquisitions between companies, changes in the e-recruitment sections (e.g., removal of application forms and substitution requesting that résumés should be sent by email), and technical problems of the websites. Taking all of these factors into account, our sample size suffers shrinkage from 76 in 2005 to 66 in 2009 (86.84% of the original sample). With respect to results and focusing on the four potentially discriminatory items (gender, marital status, number of children, and military service), we can see in Table 5 that most companies maintain their policy as regards e-recruitment (n=46, 69.70%). With reference to the rest, surprisingly, some companies have in fact increased the potentially discriminatory content (n=11, 16.67%) whilst, on the other hand, some companies have reduced their discriminatory content (n=9, 13.63%). It is worth highlighting that those companies which performed worse tend to ask for gender, which is precisely the item most directly related to gender discrimination. As we found cues of preference norm against women (Trentham & Larwood, 1998) in application forms in 2005 and 2007, we consider H1 supported.Hypothesis 2 Improvement according with the Passage of the LOIMH

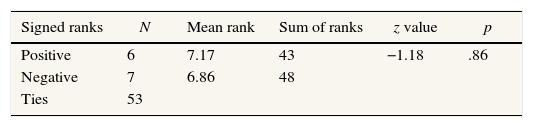

Table 6 shows the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test between companies for changes in e-recruitment practices regarding equality. As observed, differences between 2005 and 2009 are not statistically significant (z=−1.18, p ≤ .86). This means that H2 is not supported. In consequence, companies tend to maintain their policy even after LOIMH enforcement.Hypothesis 3 Legal Fulfilment and Organizational Results

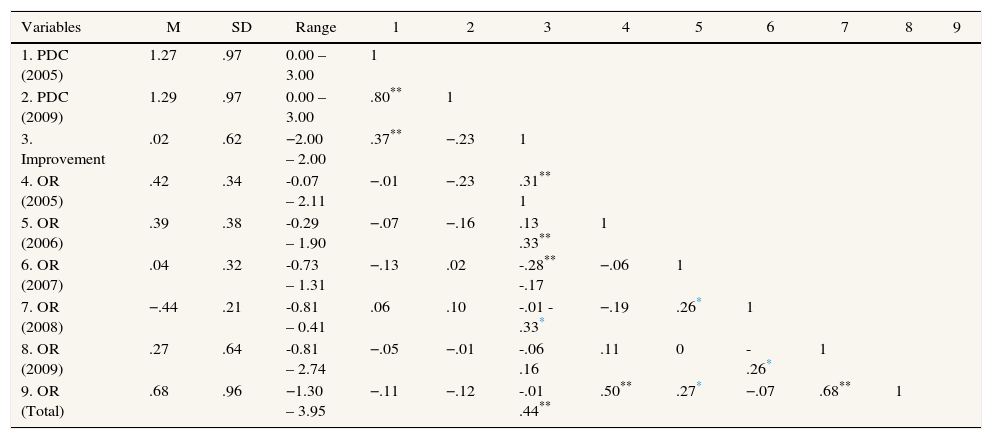

Finally, we analyzed the relationship between potentially discriminatory content and organizational results. To do this, we estimate the Spearman correlations between the variables of the study: PDC in 2005 and in 2009, improvement of e-recruitment practices, organizational results from 2005 to 2009, and the total value of organizational results. As we can see in Table 7, the PDC has shown similar descriptive statistics in 2005 and in 2009, and about one potentially discriminatory item per company (M=1.27 in 2005 and M=1.29 in 2009). With respect to organizational results, the values of annual returns varied substantially, with 2008 proving the worst year (M=-.44) and 2009 proving the best but with the highest variability (M=0.68; SD=0.96).

Spearman correlations between illegality scale, changes in policy, and annual returns.

| Variables | M | SD | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PDC (2005) | 1.27 | .97 | 0.00 – 3.00 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. PDC (2009) | 1.29 | .97 | 0.00 – 3.00 | .80** | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Improvement | .02 | .62 | −2.00 – 2.00 | .37** | −.23 | 1 | ||||||

| 4. OR (2005) | .42 | .34 | -0.07 – 2.11 | −.01 | −.23 | .31** 1 | ||||||

| 5. OR (2006) | .39 | .38 | -0.29 – 1.90 | −.07 | −.16 | .13 .33** | 1 | |||||

| 6. OR (2007) | .04 | .32 | -0.73 – 1.31 | −.13 | .02 | -.28** -.17 | −.06 | 1 | ||||

| 7. OR (2008) | −.44 | .21 | -0.81 – 0.41 | .06 | .10 | -.01 -.33* | −.19 | .26* | 1 | |||

| 8. OR (2009) | .27 | .64 | -0.81 – 2.74 | −.05 | −.01 | -.06 .16 | .11 | 0 | -.26* | 1 | ||

| 9. OR (Total) | .68 | .96 | −1.30 – 3.95 | −.11 | −.12 | -.01 .44** | .50** | .27* | −.07 | .68** | 1 |

Note. N = 66. PDC = potentially discriminatory content; Improvement = improvement of e-recruitment practices; OR = organizational results. All the correlations are one-tailed.

Focusing on the correlations, there is a strong relationship between PDC in 2005 and in 2009 (r=.80, p ≤ .01), that is, companies which have included PDC in 2005 tend to have PDC in 2009 also. There is no relationship between PDC and annual returns, but companies that obtain better organizational results in 2005 tend to make improvements in their application forms regarding equality diminishing potentially discriminatory content (r=.31, p ≤ .01); lastly, in 2007 there is an association between the improvement of e-recruitment practices and organizational results (r=-.28, p ≤ .01), which means that companies that increased their potentially discriminatory content obtained better annual returns that year. Given these results, we do not consider H3 as supported.

DiscussionWith the study described here, we show that indicators of gender discrimination in Spain were present during the recruitment process and even after the enforcement of LOIMH. Our results contribute to the scarce literature regarding gender discrimination and e-recruitment and have implications for equal opportunity policies. Companies show ambivalence in their e-recruitment sections. In contrast to our immediate expectations, recruitment statements do not include potentially discriminatory content. This evidence supports the idea that companies take substantial care of the corporate image offered by their website, avoiding cues of discrimination for attracting applicants, but when potential candidates are filling application forms, companies force them to answer potentially discriminatory items. These incongruent practices may have negative consequences for the organizations, e.g., valuable applicants could choose job offers of another organization which they perceive as being fairer (Truxillo et al., 2004). Continuing our discussion of contents, it is quite remarkable that only two companies include both genders in their word use and only one does it in a correct way.

Focusing on application forms, we can clearly state that most companies listed on Spanish Stock Exchange include potentially discriminatory content in them, even after the law enforcement. The most frequent item is related with gender, which is supported by legislation whether in terms of the nature of the particular tasks involved or in the context in which they are performed, such a characteristic constituting a genuine and determining occupational requirement, provided that the objective is legitimate and that the requirement is proportionate. Therefore, it becomes necessary to specify what we understand by a genuine and determining occupational requirement. In any event, situations like these should be more the exception than the rule. Therefore the systematic incorporation of gender proxies in application forms of companies seems unfair and potentially illegal. Posing questions concerning family and marital status also seems unfair, because their relationship with job performance is unclear. Our recommendation is to include gender only in application forms for jobs that involve situations supported by law and to remove the other three categories (military service, marital status, and number of children) in all situations.

Another interesting result is the non-significant change in the e-recruitment practices between 2005 and 2009. We hypothesize that LOIMH enforcement leads to a reduction of potentially-discriminatory content in websites, but companies maintain their application forms with the same questions, and in many cases with some additional ones. Only nine companies improve their application forms, most of them by removing the marital status category. On the other hand, eleven companies worsen their treatment with the inclusion of new potentially discriminatory proxies in their application forms, especially gender-related. Considering these results, it appears that the introduction of the LOIMH has no effect in e-recruitment practices.

With reference to organizational results, we wish to highlight the relationships existing between potentially discriminatory content on application forms and companies’ annual returns. We find that the improvement of e-recruitment practices shows a positive relationship with organizational results in 2005 but a negative one in 2007, precisely the year in which LOIMH came into force. These results suggest that the metanarrative that we proposed (legal compliance leads to better results) is not completely supported by the data. To explain this, we need to concentrate on the financial crisis which began to emerge in 2005 and continues nowadays (Amor, 2010). In fact, since 2007 there is a downward trend of organizational results and this probably affects the results of the present study. Correlations between organizational results over the years support this explanation. Additionally, as Sels et al. (2006) stress, in these types of studies it is difficult to rule out an alternative explanation for the relationships detected. We consider that our results must be analyzed carefully and that further research will help to either confirm or reject our findings.

Recommendations for Practitioners and Governmental PoliciesBased on our results, we wish to contribute the following recommendations for practitioners and the development of EEO policies. With respect to practitioners, we state here that the EU Directive 97/80 shifts the burden of proof in cases related to gender discrimination to the organization by compelling them to demonstrate that discrimination has not been committed. Furthermore, the Directive 2002/58/ EC points out the importance of adequate, accurate, and non excessive personal information. In accordance with this legislation, recruitment processes must specify how data will be collected, which data are relevant, and which people and qualification skills are necessary to process such data, as well as the conditions under which they will be processed. Our research has shown that potentially discriminatory items can be found. Therefore, we strongly recommend a revision of the application forms to ensure equality in e-recruitment. In this regard, the use of applied research is vital in order to clarify what particular data are adequate and relevant, and to what extent, with respect to candidate job entry.

We summarize our recommendations to companies and practitioners as follows: (1) in recruitment statements, use male and female gender in words; (2) avoid the use of potentially-discriminatory content in application forms; (3) include different items for different jobs, but not in the recruitment procedure in order to promote the opportunity to perform; and (4) add a statement about the commitment of the company with gender equality (e.g., “Our company is an Equal Employment Opportunities employer”), which is a common practice in other countries such the USA and the UK. By these actions companies guarantee a better legal compliance but also an improvement in applicant reactions (Bauer et al., 2006; Truxillo et al., 2004).

Our study also has implications for the development of governmental policies. Given that the LOIMH has not been as effective as expected, it probably requires additional changes to ensure its fulfilment. The LOIMH supports certain actions, such as the use of affirmative action measures, but research has consistently shown that biased decisions based on gender over merit tend to be seen as unfair by workers (e.g., Moscoso, García-Izquierdo, & Bastida, 2010; Moscoso, García-Izquierdo, & Bastida, 2012), and this has a negative impact on organizational results (e.g., Bauer et al., 2006; Truxillo et al., 2004). Therefore, it would be better developing specific guidelines for practitioners. In this sense, García-Izquierdo and Ramos-Villagrasa (2012) have proposed the use of procedural justice as a reference framework, since it has been demonstrated that organizational justice is an important determinant of attitudes, decisions, and behaviors, and consequently improves job performance and fosters behavior that promotes the effective functioning of organizations, building customer satisfaction and loyalty (Cropanzano, Bowen, & Gilliland, 2007). Moreover, employees seem to prefer transparent practices, as they are seen as antecedents of procedural justice (García-Izquierdo, Moscoso, & Ramos-Villagrasa, 2012). In line with this idea, and based on the work conducted by Gilliland (1993), and Anderson, Born, and Cunningham-Snell (2001), we recommend that legal dispositions force companies to: (1) use exclusively job-related items in their application forms; (2) give applicants the opportunity to clarify any of their answers; (3) provide information about the procedure and the evaluation process; (4) explain why potentially-discriminatory items are included for a specific job if any (if there are); (5) avoid intrusive or invasive items; (6) avoid asking for passwords or any other access to personal websites; (7) avoid requesting private information candidates could upload in social media; (8) give feedback when candidates (only candidates) ask for causes of rejection; (9) respect privacy; and (10) candidates should not be punished in the recruitment process when they defend their rights, privacy, and intimacy. However, the inclusion of these requirements in legal dispositions requires further research in relation to what kind of items are really best job-related and which circumstances should prevail to allow specific questions with respect to matters such as gender.

Limitations and Recommendations for Further ResearchThis study has certain limitations. First, it is a descriptive study, but it should be stressed that the purpose of this paper is to show the presence of potentially discriminatory content in e-recruitment sections of companies’ websites and its effect on organizational returns. Additionally, our design leads to the use of a combination of qualitative and quantitative narrative policy analysis that can be used by other researchers. Now that we have evidence showing that Spanish companies use potentially discriminatory application forms, further research should be made in relation to factors involving applicants, such as applicant reactions.

A second limitation is the degree of generalization. We have studied only the listed companies in Spain, but these results must be replicated in other samples and contexts. Research outside Anglo-Saxon countries is scarce (Aguinis, 2009), and further investigation is required to explore other cultures and the different degrees of legislation development. A third limitation is that, although the Rational Bias Theory provides support that merely the use of potentially discriminatory items could lead to discrimination, we cannot really ascertain whether a deliberate attempt at discrimination exists. Language is not neutral, so we can make inferences about subjacent values and cognitions (Riley, 2002), and the non-intrusive nature of our study allows us to capture some evidence which people would rarely recognize for use. Hence, further research needs to incorporate information as to why employers behave in this way.

In spite of those limitations, we believe that our work gives rise to new questions and recommendations for further research. In addition to the recommendations proposed for application by practitioners and for government policies, we propose extending our research efforts in the field of web-applicants perspective and e-recruitment. Further studies about how to improve application forms are also needed in order to help companies to avoid being the subject of litigations and court cases. From a gender point of view, it also seems interesting to go a step further by including other content such as nationality and disability that could be used to perform double discrimination (women who belong to another minority group). In addition, the redesign of corporate websites could also influence fairness in recruitment processes. Last but not least, other open questions are the study of the actual degree of information to be included in application forms for use in the selection process, and the comparison of the amount and relevance of such information used in both e-recruitment and traditional recruitment processes.

On the basis of all the foregoing comments, we strongly encourage on the one hand, that investigators refine studies in order to detect consistent relations between biodata and job performance and that, on the other hand, legislators as well as consulting professional and academic organizations take these studies into account, in order to provide comprehensive and accurate legislation, contributing to a wider EEO scenario.

Conflict of InterestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

Financial SupportThis manuscript has been partly supported founded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy (PSI-2013-44854-R).

The second author was working at Universidad de Oviedo during the development of this research, and his participation was funded by Universidad de Oviedo and Banco Santander (Grant: UNOV-09-BECDOC-S).

Authors want to thank Carlos Fernández (University of Oviedo, Spain) for his advice regarding organizational results. We would also like to thank Irene H. Frieze, Leire Gartzia and Esther Lopez-Zafra, and two anonymous reviewers for their help in an earlier draft of this paper.