Research has demonstrated that job complexity moderates the validity of general mental ability (GMA), the relationship between personality and job satisfaction, and the relationship between GMA and job satisfaction. However, no published research has investigated whether job complexity moderates the criterion validity of the Five-Factor Model (FFM) of personality for predicting job performance. This paper reports a meta-analytic examination of the moderator effects of job complexity on the criterion validity of the FFM of personality as assessed with forced-choice inventories. In accordance with the hypotheses, the results showed that job complexity moderates negatively the validity of conscientiousness and emotional stability and that it moderates positively the validity of openness. The implications for personnel selection research and practice are discussed.

La investigación ha demostrado que la complejidad del puesto de trabajo modera la validez de la capacidad mental general (CMG), la relación entre la personalidad y la satisfacción en el trabajo y las relaciones entre la CMG y la satisfacción en el trabajo. Sin embargo, no se ha publicado ninguna investigación que haya examinado si la complejidad del puesto de trabajo modera la validez de criterio del modelo de los cinco grandes factores (MCGF) de personalidad para predecir el desempeño en el trabajo. Este artículo presenta un metaanálisis sobre los efectos moderadores de la complejidad del puesto en la validez del MCGF de personalidad cuando se emplean cuestionarios de elección forzosa (CEF). De acuerdo con las hipótesis planteadas, los resultados muestran que la complejidad del puesto modera negativamente la validez de criterio de los factores de responsabilidad y de estabilidad emocional y positivamente la validez del factor de apertura a la experiencia. Finalmente, se plantean algunas posibles implicaciones para la teoría y la práctica de la selección de personal.

Recent surveys have shown that personality inventories are popular instruments for making personnel decisions in the United States (US) and the European Union (EU) (Alonso, Moscoso, & Cuadrado, 2015; Tett, Christiansen, Robie, & Simonet, 2011; Zibarras & Woods, 2010) and research on personality at work has also shown they are very useful procedures for predicting important organizational criteria. For example, personality measures predict job performance, training proficiency, counter-productive behaviors, well-being, accidents, productivity data, salary, promotions, and occupational attainment, among other work criteria (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Barrick, Mount, & Judge, 2001; Clarke & Robertson, 2005; Gilar, De Haro, & Castejón, 2015; Ng, Eby, Sorensen, & Feldman, 2005; Ones, Viswesvaran, & Schmidt, 1993; Poropat, 2009; Raman, Sambasiva, & Kumar, 2016; Salgado, 1997, 1998, 2002, 2003; Salgado, Anderson, & Tauriz, 2015; Salgado & Tauriz, 2014). They also predict expatriate cross-cultural adjustment and effectiveness (AlDosiry, Alkhadher, AlAqraa, & Anderson, 2016; Mol, Born, Willemsen, & Van der Molen, 2005; Salgado & Bastida, 2017).

In the domain of personality at work, the Five-Factor Model (FFM) of personality (i.e., emotional stability, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) has received more attention than any alternative model. The extant meta-analytic evidence has demonstrated that conscientiousness and emotional stability generalized validity across samples, criteria, occupations, and countries, and that the other three personality dimensions were valid predictors for specific criteria and specific occupations. For example, openness to experience predicted training proficiency, and extraversion and agreeableness predicted performance in occupations characterized by a large number of interpersonal relationships (e.g., Barrick et al., 2001; Judge, Rodell, Klinger, Simon, & Crawford, 2013).

Nevertheless, agreement is not unanimous about the relevance of personality measures for personnel selection. For example, Murphy and Dzieweczynski (2005) posited that the theories linking personality constructs and job performance were often vague and unconvincing, that little was known about how to match personality dimensions and occupations, and that some of the most valid personality-related measures (e.g., integrity tests) included poorly defined constructs. On the other hand, researchers suggested that the validity of personality measures was small and that the measures based on self-reports can be faked, independently of the administration mode (Grieve & Hayes, 2016; Morgeson et al., 2007a, 2007b; Salgado, 2016).

In part, these criticisms have been contradicted by recent research that showed that (1) the format of the personality inventories is an important moderator of the criterion-related validity of the Big Five dimensions (Salgado, Anderson et al., 2015; Salgado & Tauriz, 2014), (2) the facets of the Big Five do not show evidence of criterion-related validity for predicting job performance when the variance of the facets is residualized (Salgado, Moscoso, & Berges, 2013; Salgado, Anderson et al., 2015), and (3) there is robust evidence of the construct validity of the FFM (e.g., Judge et al., 2013). With regard to the first issue, Salgado and Tauriz (2014) and Salgado, Anderson et al. (2015) found that criterion-related validity increased noticeably when quasi-ipsative forced-choice (QIFC) formats are used. For example, the operational validity of conscientiousness was found to be .39 when a QIFC format was used. In addition, some empirical evidence showed that the forced-choice (FC) format can be more resistant to faking than the most frequently used formats, such as Likert's (Jackson, Wroblewski, & Ashton, 2000; Nguyen & McDaniel, 2000).

Therefore, there is currently empirical evidence that the FC personality inventories are valid predictors of job performance and that they are also widely used in organizations for making personnel decisions. However, no previous research has examined the potential moderator effects of job complexity on the FC inventories as a unique category, nor have the moderator effects for the particular types of FC inventories (i.e., normative, ipsative, and quasi-ipsative) been examined.

The objective of this study is to shed light on this issue that has been ignored in the meta-analytic research conducted to examine the validity of the FC personality inventories. Consequently, the main goal of this study is to meta-analytically examine whether job complexity is a moderator of the criterion validity of FC inventories. The second goal is to check whether job complexity has similar effects for the three types of FC personality scores which can be obtained from FC inventories. Thus, the main contribution of this paper lies in highlighting the role that job complexity plays in the validity of FC personality inventories for predicting job performance.

Forced-Choice Personality InventoriesThe first FC personality inventories were developed during the 1940s and 1950s (Hicks, 1970) and the FC models used in those days have remained relatively unchanged until now. Usually, the FC method asks the individual to make a choice between several alternatives, most frequently three or four. In order to make the decision the individual must indicate what alternative he/she likes most and what alternative he/she likes least when those alternatives are applied to the individual. The alternatives are paired in terms of similar levels of social discrimination and preference. Therefore, the FC method distinguishes from the most typical personality assessment methods, such as Likert, True-False, Agree-Indecisive-Disagree (collectively called single-stimulus [SS] methods), in that the individual has to make a choice between two or more alternatives rather than to rate each single statement or phase as is typically done with SS personality inventories.

Even though the FC method always consists of a choice between alternatives, the FC inventories can produce three types of scores depending on how the choice is made (Cattell, 1944; Clemans, 1966; Hicks, 1970). The FC personality inventories can result in normative, ipsative, and quasi-ipsative scores (see Salgado, Anderson et al., 2015, and Salgado & Tauriz, 2014, for a detailed account of these three scores). This contrasts with the SS personality inventories which always produce normative scores. Therefore, it is important to take into account the score type produced by the FC inventory because each of them has important psychometric characteristics.

The normative scores allow comparisons among individuals and groups on each personality variable. Therefore, they are inter-individual scores. The ipsative scores are dependent on the individual level in the other variables included in the choice. Consequently, ipsative scores permit the comparison of one individual across different personality factors. In other words, the ipsative scores are intra-individual ones. The quasi-ipsative scores allow comparisons between individuals and between groups, but produce simultaneously some degree of dependence among the variables assessed.

Several characteristics of the FC personality inventories which are relevant for personnel assessment have to be mentioned. First, they appear to correlate with general mental ability (GMA) when individuals respond as job applicants (Vasilopoulos, Cucina, Dyomina, Morewitz, & Reilly, 2006), so they can be more cognitively loaded than the typical SS personality formats (e.g., Likert, Yes, No). Therefore, the validity of the FC personality measures might be moderated by job complexity, as this variable also moderates the validity of GMA. Second, the FC-based measures may produce gender differences in some cases and, consequently, equal opportunities may also be negatively affected (Anderson & Sleap, 2004). Third, FC personality inventories showed stronger resistance to faking than SS personality inventories, although they are not totally unaffected by faking (Jackson et al., 2000; Nguyen & McDaniel, 2000). Fourth, recent advances in IRT methodology have produced methods for recovering normative scores from ipsative scores (Brown & Maydeu-Olivares, 2011; Chernyssenko, Stark, Drasgow, & Roberts, 2007; Heggestad, Morrison, Reeve, & McCloy, 2006; Maydeu-Olivares & Brown, 2010; McCloy, Heggestad, & Reeve, 2005; Stark, Chernyshenko, & Drasgow, 2005; Stark, Chernyshenko, Drasgow, & Williams, 2006). Fifth, they are currently used in around 30% of organizations, according to a survey conducted by Tett et al. (2011).

Job ComplexityHunter and Hunter (1984) defined job complexity as the cognitive difficulty of the requirements and demands of the occupation. This definition can be extended to include not only the number of complex tasks that should be solved, but also the degree to which these tasks are not repetitive, to what extent the goals are hard to define, the number of opportunities that exist for making personal decisions, and the degree to which the procedures of problem solving are not standardized. According to Hunter and Hunter, job complexity is to a great extent captured in the “data” dimension of Fine's (1955) Functional Analysis, which has defined three extensive occupational families. Other two smaller occupational families were defined by Fine's “things” dimension. Based on this scheme, Hunter and Hunter classified occupations in five big occupational families using the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT; U.S. Department of Labor, 1977/1991). These occupational families were: design (I), feed (II), synthesize (III), coordinate, analyze/compile/calculate (IV), and compare/copy (V). According to their degree of complexity, the most complex would be family I; families III and IV would be of an intermediate level of complexity, and II and V would be of low complexity. The percentage of job positions that would exist in each complexity family would be 2.5, 2.4, 14.7, 62.7, and 17.7 percent for families I, II, III, IV, and V, respectively. This means that approximately 17.2% of the occupations would be of high complexity, 62.7% would be of intermediate complexity, and 20.1% would be of low complexity. Later, Hunter and Hunter's classification was reduced to three levels of complexity by Hunter, Schmidt, and their colleagues (Hunter, Schmidt, & Judiesch, 1990; Schmidt, Shaffer, & Oh, 2008)

Job complexity is a construct that has been shown to be relevant as a moderator of the relationships between a series of individual differences variables (e.g., intelligence and personality) and also organizational variables (e.g., job performance and job satisfaction). For example, Hunter and Hunter (1984) demonstrated that job complexity moderated the validity of GMA, so higher complexity was associated with larger validity coefficients of GMA for predicting both job performance and training proficiency. This finding was later replicated by other researchers (e.g., Hartigan & Wigdor, 1989; Salgado et al., 2003; Schmidt et al., 2008). Ganzach (1998) found that job complexity moderates the relationship between intelligence and job satisfaction. Wilk and Sackett (1996) demonstrated that there is a positive relationship between job complexity and cognitive ability for people in the process of labor mobility. Judge, Bono, and Locke (2000) found that job complexity moderates the relationship between personality and job satisfaction. The moderator effects of job complexity have also been examined for the criterion validity of situational interviews (SI) and behavior-description interviews (BDI) by Huffcut, Conway, Roth, and Klehe (2004), who found moderator effects of job complexity for SIs but not effects for BDIs. However, no meta-analysis has been published to examine whether job complexity moderates the validity of personality measures in general and of those FC inventories in particular.

Job Complexity-Personality Relationships: Reasons to Expect Moderator EffectsThere are theoretical and empirical reasons to expect a moderator effect of job complexity on the validity of FC personality inventories. First, if the wide definition of job complexity mentioned above is used, i.e., the one that includes not only cognitive factors but also situational and personal ones, it could be argued that some personality factors could be related to job complexity and, therefore, job complexity could moderate the validity of these personality factors for predicting job performance. For example, Judge et al. (2000) have demonstrated that there is a moderator effect of job complexity on the relationship between personality and job satisfaction, which suggests that such moderator effects could be present in other relationships in which personality could be a determinant, such as for example job performance. In addition, some researchers have suggested that conscientiousness might not predict performance well for all occupations and situations. For example, it could be contraindicated in those occupations in which innovation, creativity, or leadership are important (Costa, Páez, Sánchez, Garaigordobil, & Gondim, 2015; Hülsheger, Anderson, & Salgado, 2009; Hough, 1997, 1998; Robertson, Baron, Gibbons, MacIver, & Nyfield, 2000; Robertson & Callinan, 1998). Given that creativity, innovation, and leadership are elements which would contribute to or reflect the complexity of a job, then job complexity would produce a negative effect on the validity of the conscientiousness dimension for predicting job performance. The implications of job complexity for emotional stability seems obvious if we take into account that the most cognitively complex jobs also tend to be characterized by their occupants having more control over and ability to decide on their behaviors and the consequences of their actions. This is the case, for example, for managers and professionals (e.g., physicians, attorneys). However, less complex jobs are more often subjected to unpredictable situations and external control. When control is associated with experiencing or not experiencing stress or having or not having emotional adjustments at work, the potential relationship between emotional stability and job complexity also seems clear. For example, the literature on “learned helplessness” is illustrative of this case (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978; Seligman, 1975). People who define situations as unpredictable and that believe that they do not control the outcomes show poorer performance, less motivation, and more negative emotional reactions. Finally, given that openness to experience shows some correlation with GMA (Judge, Jackson, Shaw, Scott, & Rich, 2007; McCrae, 1996) and that the cognitive difficulty of the tasks is an important element for defining job complexity, one would expect that job complexity moderates positively the relationship between openness and job performance, in contrast to what occurs with the dimensions of conscientiousness and emotional stability. With regard to extroversion and agreeableness, it does not seem that job complexity moderates its validity or it is at least conceptually difficult to speculate over possible relations.

Finally, as some authors (e.g., Vasilopoulos et al., 2006) have suggested that FC personality inventories can be more cognitively loaded than SS inventories, and due to the fact that job complexity moderates the relationships between GMA and job performance, some effects of job complexity on the validity of FC inventories can be expected because of their cognitive variance.

Taking all these reasons into account, the following two hypotheses can be posited:H1 Job complexity negatively moderates the validity of conscientiousness and emotional stability, so that their validity will be lower for occupations with higher complexity levels. Job complexity positively moderates the validity of the openness to experience dimension, so that the validity will be greater for the occupations with higher complexity level.

Exhaustive manual and computer-assisted searches were carried out to identify validity studies in which FC personality inventories were used and in which job performance was the criterion. The examined period covers from January 1960 to December 2015. The search was done using three strategies. First, the name of the most popular FC personality inventories (e.g., MBTI, OPQ, GPPI, EPPS) was used as a keyword in the computer searches. Second, I examined a number of proprietary electronic databases of well-known journal publishers, including Academy of Management, Ammons, Sage, Wiley, Springer, ProQuest, and Elsevier. In these searches, the terms ipsative, normative, partially-ipsative, quasi-ipsative, forced-choice, job performance, as well as the acronyms of the most popular personality inventories were used. Third, exhaustive searches were also done in Google and Scholar Google in order to identify unpublished papers. Fourth, manual searches were done in a dozen of the most important journals in which validity studies are frequently published (e.g., Journal of Applied Psychology, Journal of Occupational Psychology, Personnel Psychology, etc.). Fifth, I examined the list of references of the most highly cited meta-analyses (e.g., Bartram, 2007; Judge et al., 2013; Salgado, 1997, 2003; Salgado, Anderson et al., 2015; Salgado & Tauriz, 2014; Tett, Rothstein, & Jackson, 1991) to identify articles and unpublished papers not identified in the previous searches. Sixth, I wrote to several researchers who have conducted research on FC personality inventories and asked for published and unpublished studies. Finally, I reviewed the technical manual of the most popular FC personality inventories (e.g., D5D, EPPS, GPPI, and OPQ, among others). Once a preliminary data base of the articles, unpublished papers, technical reports, manuals, doctoral dissertations, and papers presented at conferences was created, I separated the studies that reported the relationship between personality measures and job performance and excluded the studies that used other alternative criteria (e.g., academic performance, training success, salaries, and counterproductive behavior at work). In other words, I did not include studies that used grades, instructor ratings, salaries, and reports of counterproductive behaviors as criteria. Next, I classified the scales of the inventories into the Five-Factor Model using the classification scheme of Salgado and Tauriz (2014).

If available, I recorded the following information for each study: (1) sample size, (2) occupational title, (3) type of FC measure (i.e., ipsative, quasi-ipsative, and normative), (4) personality measures, (5) criterion type, (6) predictor reliability, (7) criterion reliability, (8) range restriction in the predictor, (9) correlation between predictor and criterion, and (10) correlations among the predictors if more than one was used. In the case of studies with conceptual replications (e.g., two or more scales or inventories were used to assess the same personality factor), I used Mosier's formula to form a linear composite (Schmidt & Hunter, 2015).

Job Complexity CodingOnce the characteristics of the studies were recorded, the next step was to classify the occupations according to their respective level of job complexity. After an inspection of the jobs included in the data base, I decided to create three levels of complexity only, in accordance with the analytic strategy used by Hunter et al. (1990), Salgado et al. (2003), and Schmidt et al. (2008). The highest level of complexity consists of occupations coded 0 and 1 in the “data” dimension of the DOT and the occupations coded 0 in the “things” dimension. The medium complexity level includes the occupations coded 2, 3 and 4 in the “data” dimensions of the DOT. The lowest level of job complexity included the occupations coded 5 and 6 in the “data” dimension and the occupations coded 6 in the “things” dimension. With this classification system, the jobs included in the occupational categories of engineers, counselors, managers, lawyers, pilots, military commanders, and professionals were included in the category of high complexity. The jobs of supervisors, police, sales, customer-service representatives, clerical, mechanics, officers, and qualified personnel were included in the category of medium complexity. Finally, jobs included in the occupational categories of unskilled workers, maintenance personnel, clerical assistants, and soldiers were classified in the category of low complexity level. The classification resulted in 56 coefficients for conscientiousness, 47 for emotional stability, 47 for extroversion, 42 for agreeableness, and 40 for openness. The studies included in each complexity level-FC format combination appear in the Appendix.

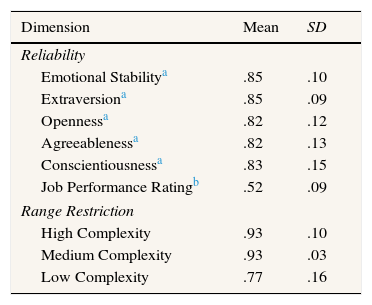

Meta-analysis Method and Artifact DistributionsAfter the studies were classified, the following step was to apply the psychometric meta-analysis method of Schmidt and Hunter (2015), implemented in a software program by Schmidt and Le (2014), which uses the correction for indirect range restriction (IRR). Sampling error, predictor reliability, criterion reliability, and range restriction (RR) were considered as artifacts that affect the validity size as well as the variance of the validity coefficients. For the criterion reliability, I used a mean value of .52 (SD=.09) which was reported by Salgado, Moscoso, and Anderson (2016; see also Salgado & Moscoso, 1996), that is also the same value found by Viswesvaran, Ones, and Schmidt (1996; see also Salgado, 2015). In the case of the reliability of the measures of the Big Five factors of personality, I used the estimates reported by Salgado and Tauriz (2014) and Salgado, Anderson et al. (2015) for the FC personality inventories.

With regard to RR, I created a distribution for each complexity level. There were two reasons for proceeding in this way. First, previous research revealed that the degree of RR is not the same across the three levels of job complexity (Salgado et al., 2003; Schmidt et al., 2008). The second reason is that the three complexity levels contain occupational categories which practically do not overlap, thereby they may have different distributions of the RR values. Therefore, if only one distribution of RR was to be used for all the jobs, then they might result in an underestimation of validity for the highly complex jobs and an overestimation of the validity for the medium and low complexity jobs. The average and the standard deviation of the distributions appear in Table 1. As can be seen in this table, the RR values of low complexity jobs are a bit lower than the values found for medium and high complexity levels. It must be noted here that RR values were practically the same for the five personality factors in each complexity level. For all the above reasons, I grouped all the coefficients of the Big Five for the same complexity level.

Predictor and Criterion Reliability Distributions and Range Restriction Distribution for the Three Levels of Job Complexity.

| Dimension | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Reliability | ||

| Emotional Stabilitya | .85 | .10 |

| Extraversiona | .85 | .09 |

| Opennessa | .82 | .12 |

| Agreeablenessa | .82 | .13 |

| Conscientiousnessa | .83 | .15 |

| Job Performance Ratingb | .52 | .09 |

| Range Restriction | ||

| High Complexity | .93 | .10 |

| Medium Complexity | .93 | .03 |

| Low Complexity | .77 | .16 |

Note.

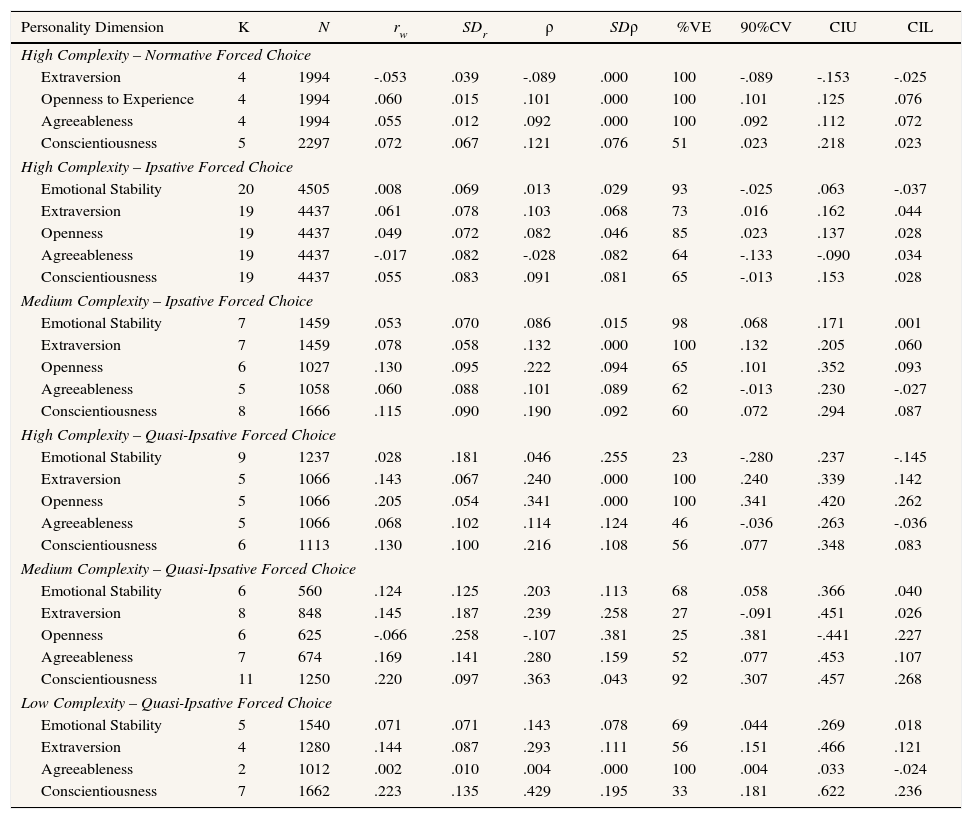

The results of the meta-analysis of the relationships between the five personality dimensions and job performance for the FC personality inventories appear in Table 2, classified according to the degree of complexity of the occupations. From left to right, the first two columns show the number of independent validities and the total sample size. The next four columns show the observed validity, the observed standard deviation, the validity corrected for measurement error in predictor and criterion, and for IRR. The last four columns report the variance accounted for by the four statistical artifacts, the 90% credibility value, and the 95% confidence interval of ρ.

Meta-analysis of the Validity of Normative FC Measures of the FFM for Managerial Occupations.

| Personality Dimension | K | N | rw | SDr | ρ | SDρ | %VE | 90%CV | CIU | CIL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Complexity – Normative Forced Choice | ||||||||||

| Extraversion | 4 | 1994 | -.053 | .039 | -.089 | .000 | 100 | -.089 | -.153 | -.025 |

| Openness to Experience | 4 | 1994 | .060 | .015 | .101 | .000 | 100 | .101 | .125 | .076 |

| Agreeableness | 4 | 1994 | .055 | .012 | .092 | .000 | 100 | .092 | .112 | .072 |

| Conscientiousness | 5 | 2297 | .072 | .067 | .121 | .076 | 51 | .023 | .218 | .023 |

| High Complexity – Ipsative Forced Choice | ||||||||||

| Emotional Stability | 20 | 4505 | .008 | .069 | .013 | .029 | 93 | -.025 | .063 | -.037 |

| Extraversion | 19 | 4437 | .061 | .078 | .103 | .068 | 73 | .016 | .162 | .044 |

| Openness | 19 | 4437 | .049 | .072 | .082 | .046 | 85 | .023 | .137 | .028 |

| Agreeableness | 19 | 4437 | -.017 | .082 | -.028 | .082 | 64 | -.133 | -.090 | .034 |

| Conscientiousness | 19 | 4437 | .055 | .083 | .091 | .081 | 65 | -.013 | .153 | .028 |

| Medium Complexity – Ipsative Forced Choice | ||||||||||

| Emotional Stability | 7 | 1459 | .053 | .070 | .086 | .015 | 98 | .068 | .171 | .001 |

| Extraversion | 7 | 1459 | .078 | .058 | .132 | .000 | 100 | .132 | .205 | .060 |

| Openness | 6 | 1027 | .130 | .095 | .222 | .094 | 65 | .101 | .352 | .093 |

| Agreeableness | 5 | 1058 | .060 | .088 | .101 | .089 | 62 | -.013 | .230 | -.027 |

| Conscientiousness | 8 | 1666 | .115 | .090 | .190 | .092 | 60 | .072 | .294 | .087 |

| High Complexity – Quasi-Ipsative Forced Choice | ||||||||||

| Emotional Stability | 9 | 1237 | .028 | .181 | .046 | .255 | 23 | -.280 | .237 | -.145 |

| Extraversion | 5 | 1066 | .143 | .067 | .240 | .000 | 100 | .240 | .339 | .142 |

| Openness | 5 | 1066 | .205 | .054 | .341 | .000 | 100 | .341 | .420 | .262 |

| Agreeableness | 5 | 1066 | .068 | .102 | .114 | .124 | 46 | -.036 | .263 | -.036 |

| Conscientiousness | 6 | 1113 | .130 | .100 | .216 | .108 | 56 | .077 | .348 | .083 |

| Medium Complexity – Quasi-Ipsative Forced Choice | ||||||||||

| Emotional Stability | 6 | 560 | .124 | .125 | .203 | .113 | 68 | .058 | .366 | .040 |

| Extraversion | 8 | 848 | .145 | .187 | .239 | .258 | 27 | -.091 | .451 | .026 |

| Openness | 6 | 625 | -.066 | .258 | -.107 | .381 | 25 | .381 | -.441 | .227 |

| Agreeableness | 7 | 674 | .169 | .141 | .280 | .159 | 52 | .077 | .453 | .107 |

| Conscientiousness | 11 | 1250 | .220 | .097 | .363 | .043 | 92 | .307 | .457 | .268 |

| Low Complexity – Quasi-Ipsative Forced Choice | ||||||||||

| Emotional Stability | 5 | 1540 | .071 | .071 | .143 | .078 | 69 | .044 | .269 | .018 |

| Extraversion | 4 | 1280 | .144 | .087 | .293 | .111 | 56 | .151 | .466 | .121 |

| Agreeableness | 2 | 1012 | .002 | .010 | .004 | .000 | 100 | .004 | .033 | -.024 |

| Conscientiousness | 7 | 1662 | .223 | .135 | .429 | .195 | 33 | .181 | .622 | .236 |

Note. K=number of independent samples; N=total sample size; rw=observed validity; SDr=standard deviation of observed validity; ρ = validity corrected for measurement error in X and Y and indirect range restriction in predictor; SDρ = standard deviation of ρ; %VE = percentage of variance accounted for by artifactual errors; 90%CV = 90% credibility value based on ρ; CIU = upper limit of the 95% confidence interval of ρ; CIL = lower limit of the 95% confidence interval of ρ.

In the case of the normative FC personality inventories, I found validity coefficients for the high complexity level only. Therefore, it was not possible to estimate the potential moderator effects of job complexity for this FC format. With very small differences, the results for the normative FC were practically the same ones reported by Salgado, Moscoso et al. (2015). The corrected validity is very small for the four personality factors included in the Table 2, although validity generalizes in the four cases, as the 90% credibility value is greater than 0.

With regard to the validity of the ipsative FC personality inventories, I found studies to compare the effects of job complexity for the occupations of high and medium complexity levels. The results indicate that validity is smaller for all the personality factors in the high complexity occupations than in the medium complexity ones. In other words, job complexity moderates validity negatively, so the larger the job complexity the lower the validity. In regard to the validity size, it is very small for the five personality factors in the case of high complexity occupations, with validity values ranging from -.028 for agreeableness to .091 for conscientiousness. There is evidence of validity generalization for extraversion and openness only. The validity size of the Big Five for the ipsative FC personality inventories in the case of medium complexity occupations is small, too, ranging from .086 for emotional stability to .222 for openness to experience. There is evidence of validity generalization for extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness, as the 90% credibility is greater than 0 in the three cases. These results partially supported Hypotheses 1 and 2.

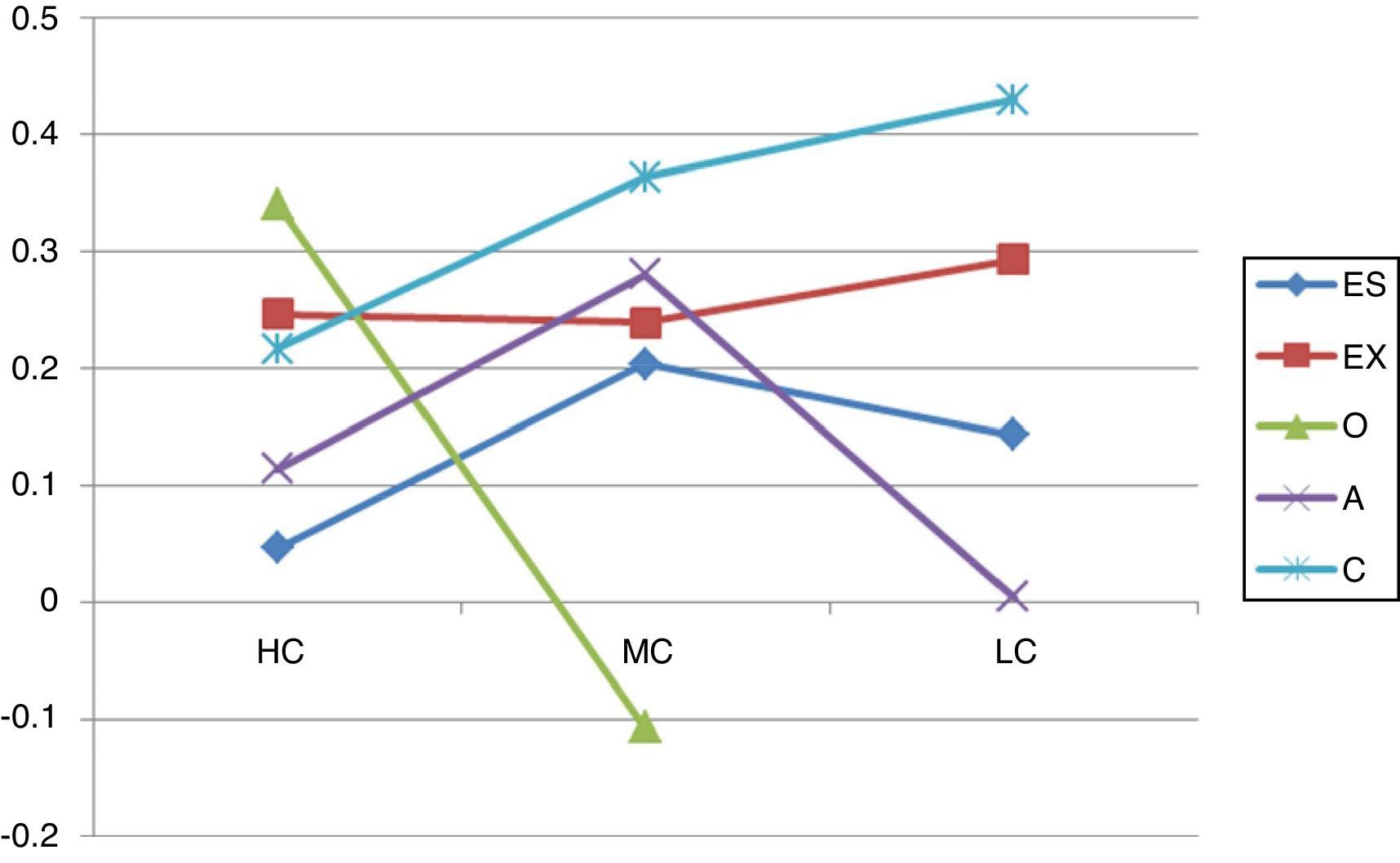

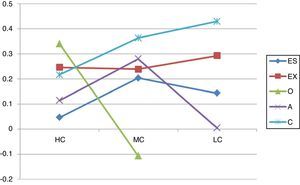

In respect to the quasi-ipsative FC personality inventories, the meta-analytic findings show that job complexity moderates the validity, although the pattern of the results vary across the five personality factors. For emotional stability, the results show that the largest validity corresponds to the occupations of the medium complexity level, followed by the lower level, and with the smallest validity for the higher complexity level. Therefore, these findings partially supported Hypothesis 1. For the three levels of job complexity, the validity size is small, ranging from .046 (high complexity) to .203 (medium complexity). In the case of extraversion, the validity is practically the same for the occupations of high and medium complexity levels (ρ=.24), and is larger for the low complexity level (ρ=.29). Therefore, the relationship between job complexity and the validity for extraversion is negative, as the validity increases when job complexity decreases. In the case of openness, I found validity studies for occupations of high and medium levels of job complexity. For this last personality factor, the validity was larger for the occupation of the high complexity level than for the medium level. Furthermore, it must be noted that the validity is considerable for the high complexity level (ρ=.34) and small and negative for the medium complexity level (ρ=-.107). Consequently, these findings totally support Hypothesis 2. The results for agreeableness show, to a certain extent, a pattern similar to the one found for emotional stability. The validity was noticeably larger for the medium level of complexity than for the other two complexity levels, but for agreeableness the second largest value was for the higher level of complexity and the validity was 0 for the lower level.

Finally, the results for conscientiousness are the most interesting for three reasons. First, they confirm that conscientiousness is consistently a valid predictor of job performance. Second, the pattern of the results showed that job complexity is an important moderator of the criterion validity of conscientiousness. The validity size ranged from .22 for the high complexity level to .43 for the lower level of complexity. The validity for the medium level was in the middle of these two. Therefore, job complexity moderated the validity of conscientiousness negatively. In other words, the findings revealed that conscientiousness is a much better predictor of job performance for the low level of job complexity than for the medium and high levels. In fact, the validity size for the low complexity level is greater than the validity of many of the most commonly used procedures in personnel selection (Schmidt & Hunter, 1998). Moreover, these findings support Hypothesis 1.

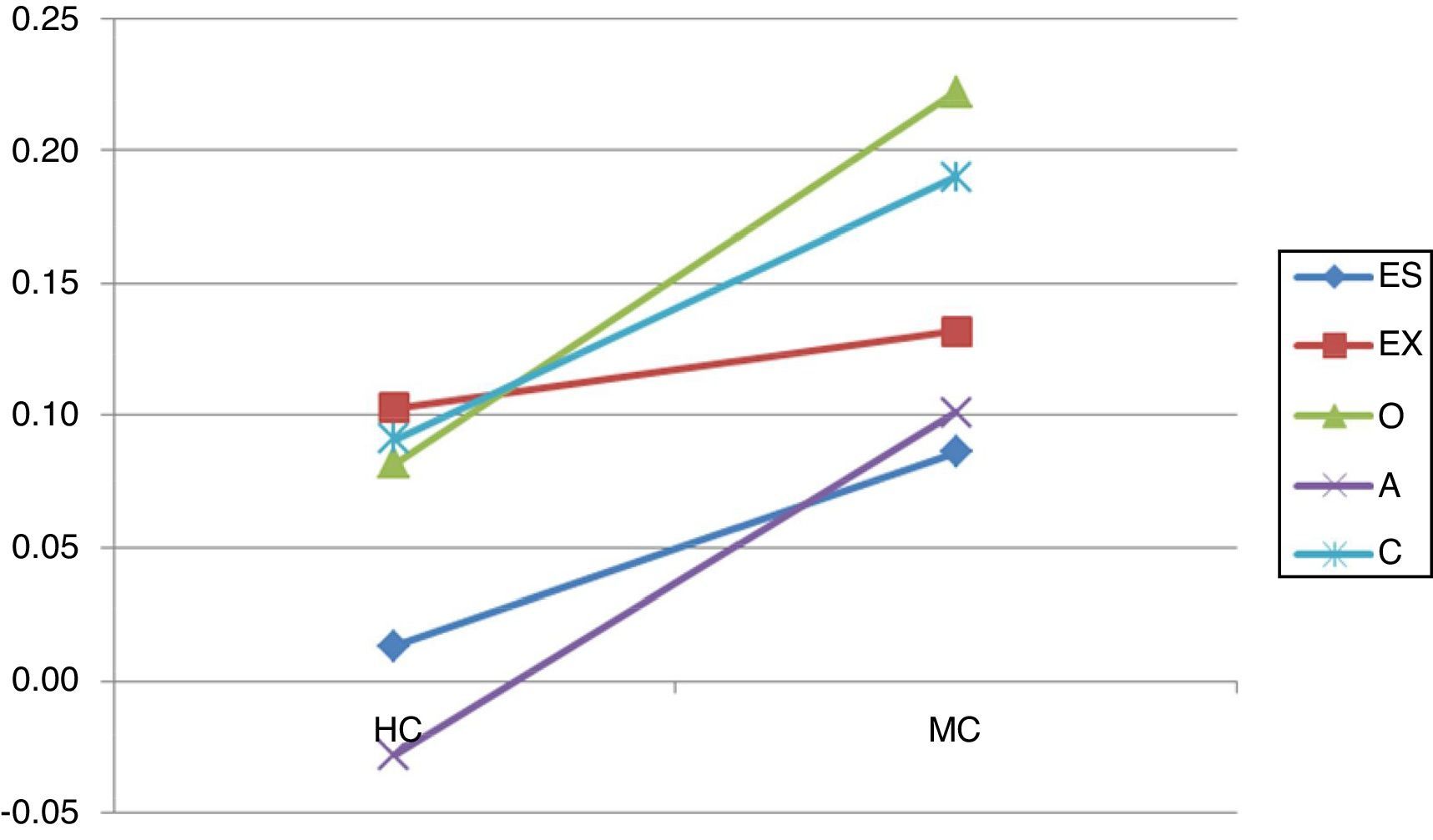

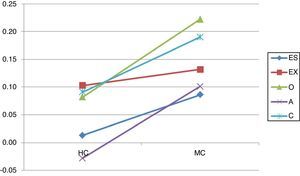

As a whole, the findings of this meta-analytic effort showed that job complexity is a relevant moderator of the validity of the five personality factors assessed with FC inventories when they are used for predicting job performance. The results supported Hypotheses 1 and 2, particularly in the case of the quasi-ipsative FC inventories. In second place, the findings showed also that there is not a single pattern of moderator effects, as can be seen in Figures 1 and 2. Finally, as conscientiousness occupies a special place among the personality factors due to the fact that it has been found to be the only factor that consistently predicted job performance, a specific comment about conscientiousness is in order. For both ipsative and quasi-ipsative FC personality inventories, the effects of job complexity run negatively with respect to the validity size. As job complexity increases, the validity of conscientiousness decreases.

This study was designed to test two hypotheses, according to which job complexity would have negative effects on the validity of conscientiousness and emotional stability (Hypothesis 1), and positive effects on the validity of openness to experience (Hypothesis 2). The results have supported Hypothesis 1, as the criterion validity of emotional stability and conscientiousness was larger for occupations of the lower levels of job complexity than for the occupations of high job complexity. The findings also supported Hypothesis 2 for both ipsative and quasi-ipsative FC personality inventories, as openness to experience was shown to be a better predictor of job performance for the occupations of high complexity level.

More specifically, in the case of conscientiousness, job complexity moderates largely and negatively the criterion validity, so that the size of the validity is smaller for the occupations of high and medium complexity in comparison with low complexity. Furthermore, the hypotheses were supported for both ipsative and quasi-ipsative FC inventories. These findings support those authors who have suggested that conscientiousness might not be such a good predictor of performance in those jobs where more flexibility, initiative, creativity and, clearly, more cognitive complexity are required (Da Costa et al., 2015; Hülsheger et al., 2009; Hough, 1997; Robertson & Callinan, 1998; Robertson et al., 2000). For both emotional stability and conscientiousness, the relationship between job complexity level and criterion validity is described by a negative linear shape.

With regard to openness to experience, the results indicated that this personality factor is a valid predictor for high complexity jobs, but that it is not a predictor for occupations of medium and low complexity level. Therefore, the relationship is described by a positive linear shape. This finding totally agreed with Hypothesis 2. Consequently, this supports the assumption that, due to the relationship between openness and GMA, the highest value for openness validity should be for high complexity level occupations.

In the case of extraversion, job complexity has no effect on its criterion validity, as for both the ipsative and the quasi-ipsative FC inventories the validity size is practically the same across the job complexity levels. The smaller differences are probably due to sampling error.

The results for agreeableness are particularly interesting and unexpected (as they were not hypothesized). Many previous meta-analyses of the FFM found that agreeableness showed very low validity or it was not a predictor at all (Barrick et al., 2001; Judge et al., 2013; Salgado & Tauriz, 2014). However, this meta-analysis shows that agreeableness can be a valid and relevant predictor of job performance for the occupations of medium complexity level, if this factor is assessed with a quasi-ipsative FC inventory. For agreeableness, the effects of job complexity on the validity take the shape of an inverted U.

In summary, the findings suggest two relevant conclusions. First, job complexity is a robust moderator of the validity of the FFM for predicting job performance of the ipsative and quasi-ipsative FC personality inventories, with the exception of extraversion. Second, the pattern (shape) of the job complexity effect is not the same for all the personality factors. Job complexity can have positive, negative, and inverted U consequences for the validity size of emotional stability conscientiousness, openness, and agreeableness, respectively. Future meta-analytic studies should be done to confirm or to refute these patterns of relationships. A third conclusion is that the average validity of the FFM reported in previous meta-analyses should be considered in the light of the present findings, as there are important differences in the validity size for the three levels of job complexity. The overall average validity used unreservedly can hide the relevant effect of job complexity for at least four of the five big personality factors.

The findings of this meta-analysis have implications for the research and practice of personnel selection and personnel decisions. The first implication for research is for the previous meta-analyses of the criterion validity of the FFM. The proportions of studies corresponding to the high, medium, and lower levels of job complexity should be examined and compared as variations in these proportions can explain the differences in the validities obtained. This fact, together with the effects of IRR (Hunter, Schmidt, & Le, 2006) and the imperfect measurement of the constructs (Salgado, 2003) can produce considerably differences in the size of the validity. From an applied point of view, when making personnel decisions practitioners should take into account the degree of job complexity to evaluate in what way and to what extent personality factors predict job performance. This implication is especially relevant with regard to agreeableness, as the results of this meta-analysis provide clues for a better understanding of how this factor works in the labor domain. Previous meta-analyses of the validity of the FFM assessed with both SS and FC personality inventories have concluded that agreeableness was a predictor that did not generalize validity across occupations in order to predict job performance (e.g., Barrick et al., 2001; Hurtz & Donovan, 2000; Salgado, 1997, 2003; Salgado & Tauriz, 2014). However, the results of the validity of agreeableness for the three levels of complexity indicate that this factor can be a valid predictor of performance in those jobs characterized by a medium level of job complexity.

There are several limitations that should be noted. The first limitation is that the number of studies has not permitted us to examine the moderator effect of job complexity for normative FC inventories. Therefore, primary studies are needed for this format. Studies are also needed for the occupations of low complexity level in the case of ipsative FC personalities. A second limitation is that the number of estimates of range restriction did not allow for the development of a specific distribution for each combination of FC format-job complexity level-personality factor. A third limitation is that a relevant number of the studies included in this meta-analysis were conducted over four decades, and it is impossible to know if the validity remained stable despite potential changes in the nature of the occupations and the measures of job performance in the last two decades. All the limitations mentioned suggest that new validity studies should be conducted, in particular taking into account that quasi-ipsative FC inventories were shown to be more valid predictors than SS personality inventories (see Barrick et al., 2001; Judge et al., 2013; Salgado, Moscoso et al., 2015), in spite of the fact that the latter are used more frequently for personnel decisions than the former.

Considering the results obtained as a whole, the final conclusion to be inferred is that job complexity is a strong moderator of the validity of personality measures. Job complexity moderates the size of validity coefficients and makes some of them (e.g. openness, agreeableness) valid predictors, when it was believed that they were not, and others were shown to have larger validity than the one obtained in previous meta-analyses, provided the analysis is based on the medium and low complexity levels (conscientiousness and emotional stability).

Conflict of InterestThe author of this article declares no conflict of interest.

Financial SupportThe research reported in this manuscript was supported by Grant PSI2014-56615-P from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and Grant 2016 GPC GI-1458 from the Consellería de Cultura, Educación e Orden, Xunta de Galicia.

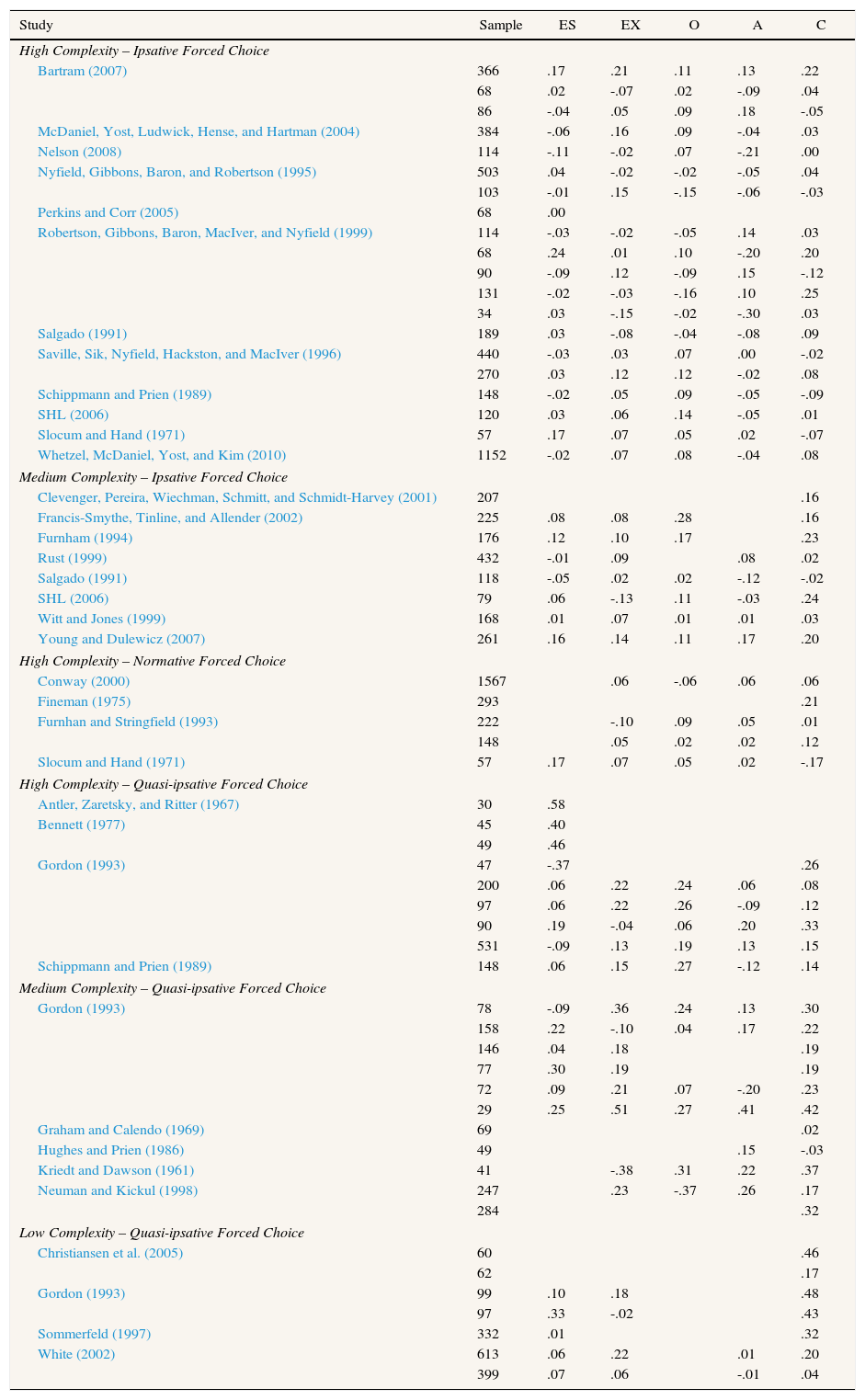

Validity Coefficients and Sample Size of the Studies Included in the Meta-analysis.

| Study | Sample | ES | EX | O | A | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Complexity – Ipsative Forced Choice | ||||||

| Bartram (2007) | 366 | .17 | .21 | .11 | .13 | .22 |

| 68 | .02 | -.07 | .02 | -.09 | .04 | |

| 86 | -.04 | .05 | .09 | .18 | -.05 | |

| McDaniel, Yost, Ludwick, Hense, and Hartman (2004) | 384 | -.06 | .16 | .09 | -.04 | .03 |

| Nelson (2008) | 114 | -.11 | -.02 | .07 | -.21 | .00 |

| Nyfield, Gibbons, Baron, and Robertson (1995) | 503 | .04 | -.02 | -.02 | -.05 | .04 |

| 103 | -.01 | .15 | -.15 | -.06 | -.03 | |

| Perkins and Corr (2005) | 68 | .00 | ||||

| Robertson, Gibbons, Baron, MacIver, and Nyfield (1999) | 114 | -.03 | -.02 | -.05 | .14 | .03 |

| 68 | .24 | .01 | .10 | -.20 | .20 | |

| 90 | -.09 | .12 | -.09 | .15 | -.12 | |

| 131 | -.02 | -.03 | -.16 | .10 | .25 | |

| 34 | .03 | -.15 | -.02 | -.30 | .03 | |

| Salgado (1991) | 189 | .03 | -.08 | -.04 | -.08 | .09 |

| Saville, Sik, Nyfield, Hackston, and MacIver (1996) | 440 | -.03 | .03 | .07 | .00 | -.02 |

| 270 | .03 | .12 | .12 | -.02 | .08 | |

| Schippmann and Prien (1989) | 148 | -.02 | .05 | .09 | -.05 | -.09 |

| SHL (2006) | 120 | .03 | .06 | .14 | -.05 | .01 |

| Slocum and Hand (1971) | 57 | .17 | .07 | .05 | .02 | -.07 |

| Whetzel, McDaniel, Yost, and Kim (2010) | 1152 | -.02 | .07 | .08 | -.04 | .08 |

| Medium Complexity – Ipsative Forced Choice | ||||||

| Clevenger, Pereira, Wiechman, Schmitt, and Schmidt-Harvey (2001) | 207 | .16 | ||||

| Francis-Smythe, Tinline, and Allender (2002) | 225 | .08 | .08 | .28 | .16 | |

| Furnham (1994) | 176 | .12 | .10 | .17 | .23 | |

| Rust (1999) | 432 | -.01 | .09 | .08 | .02 | |

| Salgado (1991) | 118 | -.05 | .02 | .02 | -.12 | -.02 |

| SHL (2006) | 79 | .06 | -.13 | .11 | -.03 | .24 |

| Witt and Jones (1999) | 168 | .01 | .07 | .01 | .01 | .03 |

| Young and Dulewicz (2007) | 261 | .16 | .14 | .11 | .17 | .20 |

| High Complexity – Normative Forced Choice | ||||||

| Conway (2000) | 1567 | .06 | -.06 | .06 | .06 | |

| Fineman (1975) | 293 | .21 | ||||

| Furnhan and Stringfield (1993) | 222 | -.10 | .09 | .05 | .01 | |

| 148 | .05 | .02 | .02 | .12 | ||

| Slocum and Hand (1971) | 57 | .17 | .07 | .05 | .02 | -.17 |

| High Complexity – Quasi-ipsative Forced Choice | ||||||

| Antler, Zaretsky, and Ritter (1967) | 30 | .58 | ||||

| Bennett (1977) | 45 | .40 | ||||

| 49 | .46 | |||||

| Gordon (1993) | 47 | -.37 | .26 | |||

| 200 | .06 | .22 | .24 | .06 | .08 | |

| 97 | .06 | .22 | .26 | -.09 | .12 | |

| 90 | .19 | -.04 | .06 | .20 | .33 | |

| 531 | -.09 | .13 | .19 | .13 | .15 | |

| Schippmann and Prien (1989) | 148 | .06 | .15 | .27 | -.12 | .14 |

| Medium Complexity – Quasi-ipsative Forced Choice | ||||||

| Gordon (1993) | 78 | -.09 | .36 | .24 | .13 | .30 |

| 158 | .22 | -.10 | .04 | .17 | .22 | |

| 146 | .04 | .18 | .19 | |||

| 77 | .30 | .19 | .19 | |||

| 72 | .09 | .21 | .07 | -.20 | .23 | |

| 29 | .25 | .51 | .27 | .41 | .42 | |

| Graham and Calendo (1969) | 69 | .02 | ||||

| Hughes and Prien (1986) | 49 | .15 | -.03 | |||

| Kriedt and Dawson (1961) | 41 | -.38 | .31 | .22 | .37 | |

| Neuman and Kickul (1998) | 247 | .23 | -.37 | .26 | .17 | |

| 284 | .32 | |||||

| Low Complexity – Quasi-ipsative Forced Choice | ||||||

| Christiansen et al. (2005) | 60 | .46 | ||||

| 62 | .17 | |||||

| Gordon (1993) | 99 | .10 | .18 | .48 | ||

| 97 | .33 | -.02 | .43 | |||

| Sommerfeld (1997) | 332 | .01 | .32 | |||

| White (2002) | 613 | .06 | .22 | .01 | .20 | |

| 399 | .07 | .06 | -.01 | .04 | ||

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.