This paper examines the indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment across different levels of equity sensitivity. The data were collected using self-reported measures from 656 permanent employees working in five commercial banks in Pakistan. The statistical results of the study confirmed that the indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment is significant. However, the statistical results of the study also demonstrated that the indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice does not differ across different levels of equity sensitivity. This study offers some implications for managers to maintain an effective employment relationship with the employees inside the organizations.

Este artículo analiza el efecto indirecto de la justicia interpersonal e informativa en la identificación con la organización a través del cumplimiento del contrato psicológico en los diferentes niveles de sensibilidad a la equidad. Por medio de medidas de autoinforme se recogieron datos de 656 empleados fijos de cinco bancos comerciales de Paquistán. Los resultados estadísticos del estudio confirman que es significativo el efecto indirecto de la justicia interpersonal e informativa en la identificación con la organización a través del cumplimiento del contrato psicológico. No obstante, dichos resultados demuestran también que el efecto indirecto de la justicia interpersonal e informativa no es distinto en los distintos niveles de sensibilidad a la equidad. El estudio propone algunas implicaciones para que los directivos mantengan una relación eficaz de empleo con los empleados en el seno de las organizaciones.

Organizational identification is a cohesive force for maintaining the relationship between employee and employer in today's increasingly complex and boundaryless organizations (Epitropaki, 2013). The research has revealed that the employees having a strong perception of organizational identification are highly likely to exhibit positive organizationally desired behaviors (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Smidts, Pruyn, & Riel, 2001). Unfortunately, the increasing organizational reliance on temporary workers, resulting from some factors, including globalization, technological advancements, and the recent financial crisis, has significantly affected employee's perceptions of organizational identification (Epitropaki, 2013; Robinson, Kraatz, & Rousseau, 1994). Moreover, the declining employee benefits (e.g., job security, rewards, and promotion) are continuously challenging their organizational identification. Consequently, employees have started realizing that employers have failed to fulfill their obligations (Epitropaki, 2013). Previous research has shown that such employee perceptions result in low levels of employee performance (Turnley & Feldman, 1999), trust (Robinson, 1996), commitment (Coyle-Shapiro & Kessler, 2000), employee engagement and citizenship behavior (Coyle-Shapiro & Kessler, 2002), and organizational identification (Epitropaki, 2013) and produce high turnover intentions (Raja, Johns, & Ntalianis, 2004).

There is a mutual consensus among the scholars of the employment relationship discipline that the deteriorating perceptions of employee's organizational identification can be repaired by fulfilling the psychological contract of the employees. Particularly, they believe that the employees’ tendency to identify with their organizations is highly reliant on the tendency of the employer to fulfill the psychological contract (PC). Thus, the organizational scholars (Masterson & Stamper, 2003; Rousseau, 1998) have conducted research to identify mechanisms for maintaining the employment relationship, particularly studying the relationship between psychological contract and organizational identification. Masterson and Stamper (2003) proposed a model of perceived organizational membership framework and demonstrated that psychological contract and organizational identification are the two sub-dimensions of this framework. They recommended advancing research on the relationship between sub-dimensions of this framework by considering the contextual variables. Recently, Epitropaki (2013) investigated the interrelationship between psychological contract breach and organizational identification by considering procedural justice as a contextual variable. The psychological contract breach and psychological contract fulfillment are two conceptually different variables on a fulfillment-breach continuum (Bal, Chiaburu, & Diaz, 2011; Conway, Guest, & Trenberth, 2011); yet, psychological contract breach has different effects on employee outcomes as compared to psychological contract fulfillment (Conway et al., 2011). Previous research has shown various positive outcomes of psychological contract fulfillment, like affective commitment and in-role and extra-role performance (Chen, Tsui, & Zhong, 2008; Coyle-Shapiro & Kessler, 2002; Robinson et al., 1994; Zhao, Wayne, Glibkowski, & Bravo, 2007). Although the recent stream of research is focusing more on the negative aspects of perceived organizational membership, yet there is still a need to examine the extent to which an organizational focus on positive aspects of perceived organizational membership strengthens the employment relationship. This is more interesting for a better explanation of the employment relationship mechanisms to incorporate the effect of some contextual variables whilst investigating the relationship of psychological contract fulfillment with other sub-dimensions of perceived organizational membership framework. The objective of the current study is to extend the research on the interrelationship between different sub-dimensions of perceived organizational membership framework by investigating the impact of psychological contract fulfillment on organization identification. Moreover, this study has considered organizational justice as a contextual variable of the interrelationship between psychological contract fulfillment and organizational identification. The two dimensions of organizational justice, i.e., interpersonal and informational justice, explain a significant proportion of justice perceptions of an employee as compared to the procedural and distributive justice (Mikula, Petrik, & Tanzer, 1990). Moreover, interpersonal and informational justice may also have a significant effect on reducing the risks associated with various current organizational issues like downsizing (Molinsky & Margolis, 2006). Thus, we investigated the indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment.

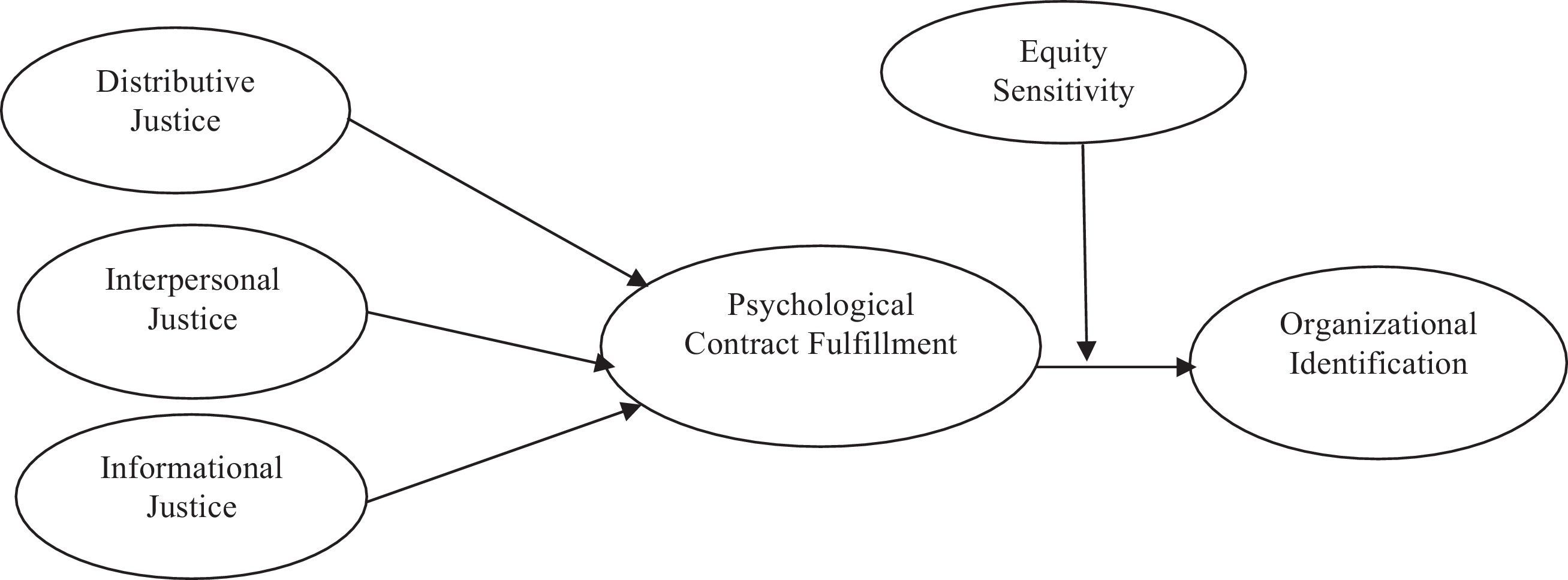

Since individual differences also affect the employment relationship (Ho, Weingart & Rousseau, 2004; Kickul & Lester, 2001; Raja et al., 2004), we have also proposed equity sensitivity as an individual difference in the overall indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through the psychological contract fulfillment. Equity sensitivity is an individual difference explained by the equity theory that represents an individual's unique sensitivity to equity which leads individual's reactions to the perceived inequity (King, Miles, & Day, 1993). The theoretical support for the study is obtained from the perceived organizational membership framework (Masterson & Stamper, 2003), cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957), social identity theory (Tajfel, 1978, 1979), the social identity view of dissonance theory (McKimmie et al., 2003), and the equity theory (Adam, 1965). The forthcoming section of the study discusses the theoretical foundation of hypotheses.

Theory and HypothesesOrganizational Justice and Psychological Contract FulfillmentOrganizational justice is one of the factors affecting employee's perception of psychological contract (Epitropaki, 2013; Morrison & Robinson, 1997; Shore & Tetrick, 1994; Tekleab, Takeuchi, & Taylor, 2005). Organizational justice refers to employee's perception of fairness within an organization (Greenberg, 1990). Organizational justice communicates the message of respect and dignity to employees, that makes them feel proud to be members of a particular organization (Tyler & Blader, 2003; Epitropaki, 2013). Four different dimensions of organizational justice include procedural justice, distributive justice, and interpersonal and informational justice (Colquitt, 2001; Greenberg, 1993). The effect of organizational justice on the psychological contract remained the key focus of existing research on employment relationship. For instance, Shore and Tetrick (1994) examined the effect of distributive and interactional justice on the transactional and relational psychological contract; Tekleab et al. (2005) examined the impact of procedural justice and interactional justice on the psychological contract voilation; and Epitropaki (2013) investigated the effect of procedural justice on the psychological contract breach. However, the impact of interpersonal and informational justice on the psychological contract fulfillment remained overlooked. We intend to fill this void by investigating the impact of interpersonal and informational justice on psychological contract fulfillment.

Interpersonal justice is the degree to which people are treated with politeness, respect, and dignity during the implementation of procedures in a particular organization, while informational justice is the degree to which people receive information and explanation about how certain procedures are implemented and outcomes are distributed in the organization (Colquitt, 2001; Cropanzano, Byrne, Bobocel, & Rupp, 2001; Greenberg, 1990). Fair treatment represents interpersonal justice and fair communication represents informational justice and the level of both interpersonal and informational justice significantly affect the employment relationship (Cropanzano, Prehar & Chen, 2002; Greenberg, 1990; Masterson, Lewis, Goldman, & Taylor, 2000; Rupp & Cropanzano, 2002; Siegel, Christian, Garza, & Ellis, 2012; Sweeney & McFarlin, 1993). Interpersonal and informational justice is also an important input for employees to assess the quality of their relationship with their organization (Masterson et al., 2000).

In various situations, events, actions, and perceptions are more critical in psychological contracts as compared to formal procedures; therefore, fair interpersonal treatment is one of the most important antecedents of psychological contract (Morrison & Robinson, 1997). Supervisors are organizational representatives who disseminate information to their subordinates; therefore, employees consider them liable for fulfillment of their expectations (Folger & Cropanzano, 1998; Masterson et al., 2000; Moorman, 1991). Fair communication is also one of the most important antecedents of psychological contract (Morrison & Robinson, 1997). The norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960) demonstrates that the individuals react positively if they receive the expected responses from others. For instance, providing a realistic job review to new entrants may ease their socialization within the organization and the employee may develop the perceptions of psychological contract fulfillment. Similarly, the perceptions of psychological contract fulfillment may develop within employees when they are receiving fair interpersonal treatment from their supervisors. Employees are highly likely to develop a perception of fairness if they are treated with respect (interpersonal justice), and provided honest explanations during their interactions with authorities (informational justice; Bies & Moag, 1986; Colquitt, 2001; Greenberg, 1993; Zhang, LePine, Buckman, & Wei, 2014). The cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957) explains that cognitive inconsistencies result in psychological costs and problems. Yet, employees are less likely to experience such cognitive inconsistencies in case of a high level of perceived interpersonal and informational justice. Thus, if employees perceive that their supervisors have treated them fairly and provided them fair information, they are highly likely to perceive the psychological contract fulfillment. Based on the above arguments, we hypothesized that there is a positive relationship between employees’ perceived interpersonal and informational justice and psychological contract fulfillment.

H1a. Interpersonal justice is positively related to psychological contract fulfillment.

H1b. Information justice is positively related to psychological contract fulfillment.

Psychological Contract Fulfillment and Organizational IdentificationOrganizational identification and psychological contract both are sudimensions of the perceived organizational membership (POM) framework presented by Masterson and Stamper (2003). POM is an aggregate construct that consists of need fulfillment, mattering, and support. Organizational identification refers to an individual's perception of ‘belongingness’ with an organization (Haslam & Platow, 2001). Organizational identification is the sub-dimension of ‘mattering’ whereas psychological contract is the subdimension of ‘need fulfillment’ (Masterson & Stamper, 2003). Organizational identification is positively related to employee extra role performance and job satisfaction and negatively related to turnover intentions and counterproductive work behaviors (Abrams, Ando, & Hinkle, 1998; Blader & Tyler, 2009; Chughtai & Buckley, 2010; Haslam & Platow, 2001; Mael & Ashforth, 1995; van Knippenberg & van Schie, 2000). On the other hand, psychological contract is a sub-dimension of the ‘need fulfillment’ construct of POM framework (Masterson & Stamper, 2003). Psychological contract fulfillment refers to employees’ perceptions about the extent to which their needs are fulfilled inside an organization. Psychological contract fulfillment affects employee's attitude towards the organization (Masterson & Stamper, 2003; Rousseau, 1989). Thus, psychological contract fulfillment can positively influence employees’ perception of organizational identification. Social identity is an individual's perception of belonging to a social group (Tajfel, 1978, p. 292). The social identity theory (Tajfel, 1979) explains that individuals who are striving for a positive social identity either leave a group or join another group when they perceive that their social identity is not satisfactory (Tajfel, 1979). The psychological contract fulfillment can maintain the positive social identity of employees within an organization. Epitropaki (2013) utilized the social identity view of the dissonance theory (McKimmie et al., 2003) to support the proposition that psychological contract breach is positively related to organizational identification. They argued that employees would reduce their identification with the organization due to the cognitive dissonance resulting from the psychological contract breach. We are also borrowing the same theoretical lens to argue that employees are less likely to experience cognitive dissonance in case of psychological contract fulfillment. Thus, employees are highly likely to identify themselves with the organization. Kreiner (2002) found positive association between psychological contact fulfillment and organizational identification. A recent study by De Ruiter, Lub, Jansma, & Blomme (2016) has also found a positive association of expatriate employee's psychological contract fulfillment with their identification with multinational corporations. Based on the previous arguments and empirical results, we have hypothesized that the fulfillment of employee's psychological contract is positively associated with organizational identification.

H2. Psychological contract fulfillment is positively related to organizational identification.

Mediating Role of Psychological Contract FulfillmentThe research has provided some empirical evidence about the chain relationship of organizational justice, psychological contract, and employees’ attitudes and behaviors (Epitropaki, 2013; Shore & Tetrick, 1994; Tekleab et al., 2005). This study adds to this stream of research by investigating the mediating role of psychological contract fulfillment between organizational justice and organizational identification. Masterson et al. (2000) recommended researchers to use the social exchange theory for examining employee outcomes of organizational justice through mediating variables. We found that psychological contract is an appropriate intervening variable in the relationship between organizational justice and organizational identification. Recently, Epitropaki (2013) investigated the mediating role of psychological contract breach between procedural justice and organizational identification. Previous research has ignored the effect of two key dimensions of organizational justice, i.e., interpersonal and interactional justice, on employment relationship. This study aims to fill this research gap by investigating the impact of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment.

The employees use psychological contract to evaluate their experiences with their employer (Epitropaki, 2013). Fair treatment of a supervisor to an employee represents interpersonal justice, while fair explanation provided to employees about organizational decisions or procedures represents informational justice. Interpersonal justice and informational justice positively affect employees’ pride and self-regard and lead them to psychologically associate with the organization (Fuchs & Edwards, 2012). However, we argue that the psychological contract fulfillment strengthens the relationship between two dimensions of organizational justice and organizational identification. According to Masterson et al. (2000), employees assess the quality of their relationship with their organization based on fair interpersonal treatment and fair explanations. Employees feel respected and valued when a supervisor treats them fairly and provides them fair explanations about organizational procedures (Epitropaki, 2013; Tyler & Lind, 1992). The employee is less likely to experience cognitive inconsistencies in case of fair interpersonal treatment and fair explanations. Therefore, the employee is highly likely to perceive fulfillment of the psychological contract. Further, employees will feel obliged to develop a sense of inclusion in the organization (Armstrong-Stassen & Schlosser, 2011). Thus, the employee is highly likely to identify themselves with their organization (Epitropaki, 2013; Tyler & Blader, 2003). Based on these arguments, we hypothesized that the psychological contract fulfillment mediates the relationship of interpersonal and informational justice with organizational identification.

H3a. Psychological contract fulfillment mediates the relationship between interpersonal justice and organizational identification.

H3b. Psychological contract fulfillment mediates the relationship between informational justice and organizational identification.

Moderating Role of Equity SensitivityEpitropaki (2013) recommended future researchers to examine the role of equity sensitivity as an additional explanatory construct in the relationship between psychological contract and organizational identification. This study also aimed at investigating the role of equity sensitivity as a moderator between psychological contract fulfillment and organizational identification. Equity sensitivity explains a manager's sensitivity to different fair and unfair situations that could affect their attitudes and behaviors (Huseman, Hatfiel, & Miles, 1985, 1987; King et al., 1993). Individuals can be categorized into three distinct groups based on their sensitivity to equity: (a) benevolent, (b) equity sensitive, and (c) entitled (Huseman et al., 1985, 1987). Benevolent employees are organizational ‘givers’ who want to maintain a good relationship with their employers and feel more satisfied when their input exceeds their output (Huseman et al., 1987). The cognitive dissonance theory explains that people attempt to maintain a cognitive consistency between their perceptions, actions, and behaviors. Since employees who have a benevolent personality value work and feel greater satisfaction by contributing more to their organizations (Restubog, Bordia, & Tang, 2007), they are highly likely to develop perceptions of psychological contract fulfillment in response to interpersonal and informational justice to maintain the level of their cognitive consistency. Similarly, they are also highly likely to perceive higher organizational identification as a result of psychological contract fulfillment. Thus, the effect of the psychological contract fulfillment on organizational identification will be stronger if employees have a benevolent personality.

Benevolent employees are less affected by the psychological contract breach as compared to entitled and equity sensitive employees (Restubog et al., 2007). On the other hand, entitled employees seek for more rewards than their contribution to their organizations (King et al., 1993). Employees who are entitled are more sensitive to equity as compared to benevolent ones, so they are more vigilant in ensuring that promises made by their organization are adequately fulfilled (Raja et al., 2004). Since entitled employees seek for more rewards, their tendency to maintain cognitive consistency between perceptions, actions, and attitudes would be low as compared to benevolent and equity sensitive employees. Thus, the effect of psychological contract fulfillment on organizational identification will be weaker if employees have an entitled personality. The third kind of individuals is equity sensitive, who lie in the middle of entitled and benevolent with respect to their sensitivity to equity (Huseman et al., 1985, 1987). Since equity sensitive individuals give equal value to both work and reward (Huseman et al., 1985, 1987), their tendency to maintain cognitive consistency between perceptions, actions, and attitude would be greater than entitled ones’ but less than benevolent individuals’. Thus, the effect of psychological contract fulfillment on organizational identification will be moderate if employees have an equity sensitive personality. Based on the above arguments, we have hypothesized that:

H4. Equity sensitivity moderates the relationship between psychological contract fulfillment and organizational identification such that:

H4a. The strength of the relationship is stronger if employees have a benevolent personality.

H4b. The strength of the relationship is moderate if employees have an equity sensitive personality.

H4c. The strength of the relationship is weaker if employees have an entitled personality.

Indirect Effect across Different Levels of Equity SensitivityThe overall pattern of the hypotheses developed in the current study indicated a moderated mediation mechanism where an indirect effect is contingent to the level of a third variable (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). Equity sensitivity is a personality trait that may regulate the indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment. Depending upon the level of equity sensitivity of individuals, we believed that the strength of the overall mediating role of psychological contract fulfillment would differ with respect to employees’ equity sensitivity.

We have also discussed that individuals are highly inclined to maintain a cognitive consistency between their perceptions, actions, and behaviors (Huseman et al., 1985, 1987) to avoid the psychological costs of cognitive dissonance (cognitive dissonance theory). On the other hand, the equity theory (Adams, 1965) explains that individuals compare the ratio of their inputs and outcomes with others. An integration of the cognitive dissonance theory and the equity theory allows us to argue that individuals experience cognitive dissonance due to their tendency of comparing their contributions and inducements with others’. Equity sensitivity is based on the equity theory and refers to an individual's sensitivity to different fair and unfair situations that could affect their attitudes and behaviors (Huseman et al., 1985, 1987; King et al., 1993). Thus, the strength of the overall indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment also depends upon the level of an employee's equity sensitivity. A benevolent employee values work and feels greater satisfaction by contributing to their organization (Restubog et al., 2007). Thus, we argue that the indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment will be stronger if employees have a benevolent personality. The equity sensitive employee gives equal value to both work and reward (Huseman et al., 1985, 1987). Thus, the indirect effect will be moderate if employees have an equity sensitive personality. Entitled employees seek for more rewards than their contribution to the organization (King et al., 1993). Thus, the indirect effect will be weaker if employees have an entitled personality. Thus, we argue that the indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment will be weaker if employees have a benevolent personality. Based on the above discussion, we hypothesized that equity sensitivity moderates the indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment.

H5a. The indirect effect of interpersonal justice on organizational identification via psychological contract fulfillment would differ across different levels of equity sensitivity such that:

- a.

The indirect effect will be stronger if employees have a benevolent personality.

- b.

The indirect effect will be moderate if employees have an equity sensitive personality.

- c.

The indirect effect will be weaker if employees have an entitled personality.

H5b. The indirect effect of informational justice on organizational identification via psychological contract fulfillment differs across different levels of equity sensitivity such that:

- a.

The indirect effect will be stronger if employees have a benevolent personality.

- b.

The indirect effect will be moderate if employees have an equity sensitive personality.

- c.

The indirect effect will be weaker if employees have an entitled personality (Figure 1).

The participants of the current study were permanent employees, with a minimum of one-year experience, working in the top five commercial banks located in the province of Punjab, Pakistan. We distributed a survey questionnaire among 700 respondents; 656 participants returned completely filled questionnaires. The response ratio was 93%. Since English is the official language in Pakistan, we administered all the questionnaires in English. The sample consisted of 75% male and 25% female respondents. Respondents holding bachelors degree were 66%, 32% respondents held master degree, 1.4% respondents were having intermediate level education, and 0.6% respondents held PhD degree. The average experience of 65% employees was 1-5 years, while 18 percent respondents had an average experience of 6-10 years. The average age of 25% respondents ranged from 20 to 25 years, 45% were 26-30 years old, 24% were 31-35 years old, and the remaining 10% were more than 41years old.

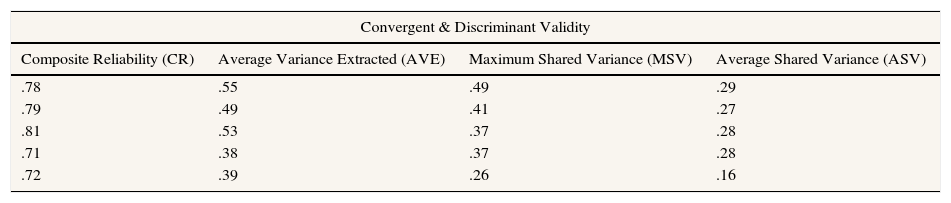

MeasuresInterpersonal and informational justiceWe measured interpersonal and informational justice using the scale developed by Colquitt (2001). This scale contains four items for measuring interpersonal justice and five items for measuring informational justice. We requested the respondents to provide responses with respect to their interactions with their supervisors and the explanations provided by him about carrying out procedures for distributing job outcomes (like pay, incentives, or promotion). Respondents provided their ratings on a five-point rating scale ranging from 1 (to a small extent) to 5 (to a large extent). A sample item for interpersonal justice was: “To what extent does she/he treat you in a polite manner.” A sample item for informational justice was: “She/he has been candid in communications with you.” The reliability of the four items of interpersonal justice was .78 and the reliability of four items of informational justice was .79.

Psychological contract fulfillment (PCF)Psychological contract fulfillment was measured using a five-item scale developed by Robinson and Morrison (2000). A sample item was: ‘Almost all promises made by my employer during recruitment have been kept so far.’ The responses provided their ratings on a five-point rating scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The overall reliability of the scale was .70.

Organizational identificationOrganizational identification was measured using a 5-item scale developed by Mael and Ashforth (1995). A sample item was: “I feel strong ties with my organization.” The responses were obtained on a five point rating scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Equity sensitivityEquity sensitivity was measured using a 5-items forced choice scale developed by Huseman et al. (1987). We followed the approach of Taylor, Kleumper and Sauley (2009) and rephrased all items with the phrase: “In an organization that I might work.” Then, we obtained responses on 10-items. A sample item was: “It is important for me to give to the organization.” Finally, we summed the scores of the respondents allocated to the benevolent responses.

Control VariablesWe also controlled for the effects of some individual level variables (gender, age, education, and organizational tenure, in years) with current employees due to their potential impact on the dependent variable. Previous research has indicated that older people experienced relatively stable psychological contracts and reacted differently than younger people (like Bal, De Lange, Jansen, & Van der Velde, 2008). Similarly, Raja et al. (2004) found that the dynamics of psychological contract change over the course of an individual's career and tenure positively affects employee identification (e.g., Mael & Ashforth, 1995). Thus, we also controlled for the effect of employee age and job tenure with the current employer.

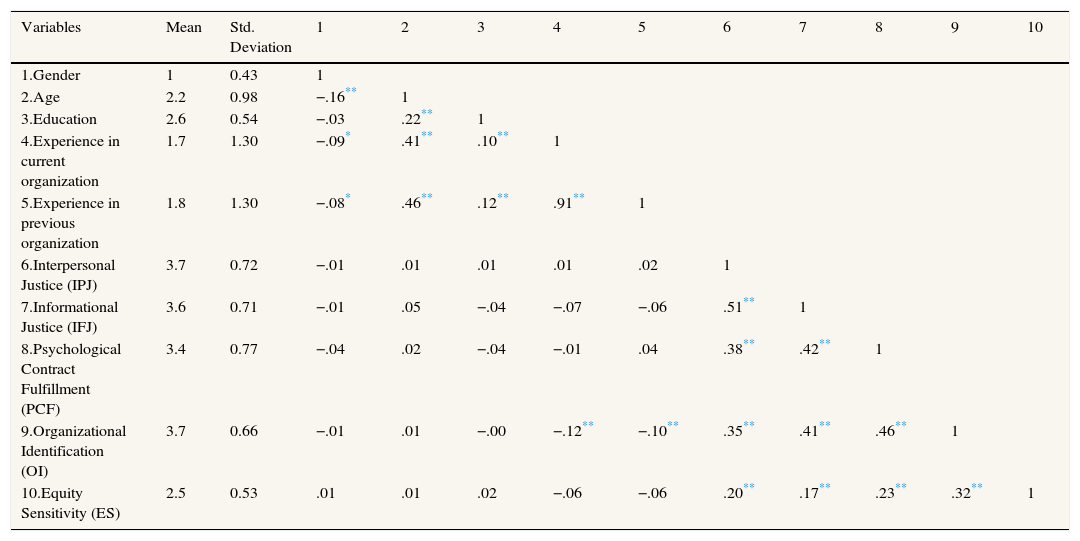

Analytical ProcedureThe data analysis procedure started with checking preliminary assumptions of regression. Mean, standard deviation, and correlations among variables are given below in Table 1.

Mean, Standard Deviation, and Correlations.

| Variables | Mean | Std. Deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Gender | 1 | 0.43 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2.Age | 2.2 | 0.98 | −.16** | 1 | ||||||||

| 3.Education | 2.6 | 0.54 | −.03 | .22** | 1 | |||||||

| 4.Experience in current organization | 1.7 | 1.30 | −.09* | .41** | .10** | 1 | ||||||

| 5.Experience in previous organization | 1.8 | 1.30 | −.08* | .46** | .12** | .91** | 1 | |||||

| 6.Interpersonal Justice (IPJ) | 3.7 | 0.72 | −.01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .02 | 1 | ||||

| 7.Informational Justice (IFJ) | 3.6 | 0.71 | −.01 | .05 | −.04 | −.07 | −.06 | .51** | 1 | |||

| 8.Psychological Contract Fulfillment (PCF) | 3.4 | 0.77 | −.04 | .02 | −.04 | −.01 | .04 | .38** | .42** | 1 | ||

| 9.Organizational Identification (OI) | 3.7 | 0.66 | −.01 | .01 | −.00 | −.12** | −.10** | .35** | .41** | .46** | 1 | |

| 10.Equity Sensitivity (ES) | 2.5 | 0.53 | .01 | .01 | .02 | −.06 | −.06 | .20** | .17** | .23** | .32** | 1 |

Then, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine the overall structure and construct validity. The factor loadings of the final confirmatory factor analysis model (χ2=313.7, df =142; CMIN/df=2.209; RMR=.029; CFI=.957; TLI=.948; IFI=.957; RMSEA=.043; and PCLOSE=.965) ranged from .59 to .89. These factor loadings were used to estimate convergent and discriminant validity of all variables that is given below in Table 2. Further, the ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom was 2.48. The value is less than 3 and represents a good fit (Carmines & McIver, 1981).

We also examined common method variance in the data using two different tests. First, we performed Harman's single-factor analysis (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986) using exploratory factor analysis where all items of the variables were restricted to load on a single factor. This single factor explained 22.5% of variance, that was far below the threshold level of 40% described by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff, (2012). Second, we performed confirmatory factor analysis by adding a common latent factor that was connected with all observed variables of the model. We constrained all paths between observed variables and the common latent factor to be equal and compared its results with the results of an initial CFA model. The results demonstrated that this model only explained 3 to 4% of shared variance in all latent factors of the study. This ensured that common method variance was not an issue in this study.

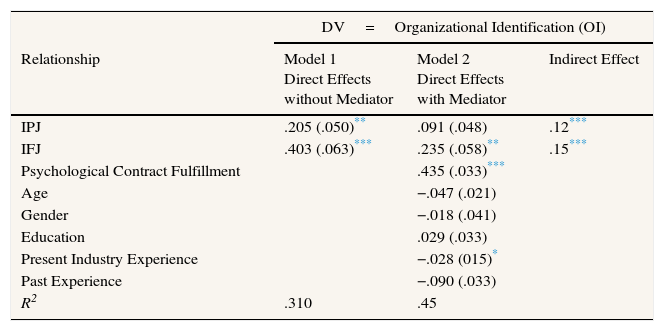

ResultsMediation AnalysisWe used AMOS (5th version) for testing a mediation hypothesis in the guidelines of Preacher and Hayes (2004) through structural equation modeling. We tested two different structural regression models. The first structural regression was tested to assess the direct effect of Interpersonal Justice (IPJ) and Informational Justice (IFJ) on Organizational Identification (OI). This model did not contain mediating variable (Psychological Contract Fulfillment). We found that interpersonal justice (β=.205, p<.01) and informational justice (β=.403, p<.001) were both positively associated with organizational identification. Then, we tested a second structural regression model that also contained the mediator. We used 5,000 bootstrapping samples with 95% bias-corrected confidence interval as suggested by Preacher and Hayes (2004). The results demonstrated that both interpersonal (β=.296, p<.001) and informational justice (β=.348, p<.001) were positively associated with the mediating variable i.e., psychological contract fulfillment (PCF). These statistical results supported hypotheses H2a and H2b. We also found that psychological contract fulfillment (β=.435, p<.001) was also positively related to organizational identification. These results supported our Hypothesis 1.

Then, we interpreted two-tailed standardized indirect effects of both interpersonal (p<.001) and informational justice (p<.001) on organizational identification via psychological contract fulfillment using 5,000 bootstrapping samples. The significant values of the standardized indirect effects demonstrated statistical support for hypotheses H3a and H3b (Table 3).

Results of Structural Regression Model Examining Mediating Role of Psychological Contract Fulfillment in the Relationship of Informational Justice and Interpersonal Justice and Organizational Identification.

| DV=Organizational Identification (OI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | Model 1 Direct Effects without Mediator | Model 2 Direct Effects with Mediator | Indirect Effect |

| IPJ | .205 (.050)** | .091 (.048) | .12*** |

| IFJ | .403 (.063)*** | .235 (.058)** | .15*** |

| Psychological Contract Fulfillment | .435 (.033)*** | ||

| Age | −.047 (.021) | ||

| Gender | −.018 (.041) | ||

| Education | .029 (.033) | ||

| Present Industry Experience | −.028 (015)* | ||

| Past Experience | −.090 (.033) | ||

| R2 | .310 | .45 | |

Note. N = 656. Beta coefficients are reported in parentheses. Model Fit 1 (without mediator): chi-square=301.704, df=144, CMIN/df=2.095, RMSEA= .041, RMR=.035, CFI=.967, IFI=.967, TLI=.956, PCLOSE=.990.

Model Fit 2 (with mediator): chi-square=129.8, df=41, CMIN/df=3.167, RMSEA= .058, RMR=.029, CFI=.958, IFI=.959, TLI=.944, PCLOSE=.126.

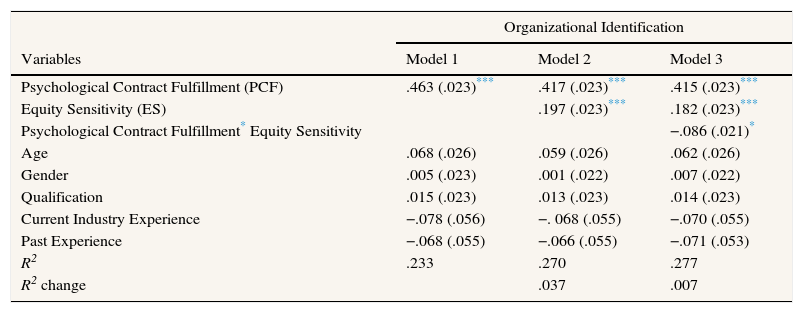

Then, we tested the three conditions of Baron and Kenny (1986) using a moderated regression analysis to examine the interaction effect of Psychological Contract Fulfillment (PCF) and Equity Sensitivity on Organizational Identification (Condition 2). We created an interaction term using standardized values of the independent and moderating variables. In the first step, we entered Psychological Contract Fulfillment (PCF) as an independent variable, then we entered equity sensitivity as moderator, and finally we entered the product term of Psychological Contract Fulfillment (PCF) and Equity Sensitivity. The results (given in Table 4) show that the main effect of PCF (β=.415, p<.05), equity sensitivity (β=.182, p<.05), and their interaction term (β=-.086, p<.05) were significant.

Results of Regression Analysis Examining Moderating Effects of Psychological Contract Fulfillment (PCF) and Equity Sensitivity (ES) on Organizational Identification (OI).

| Organizational Identification | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| Psychological Contract Fulfillment (PCF) | .463 (.023)*** | .417 (.023)*** | .415 (.023)*** |

| Equity Sensitivity (ES) | .197 (.023)*** | .182 (.023)*** | |

| Psychological Contract Fulfillment* Equity Sensitivity | −.086 (.021)* | ||

| Age | .068 (.026) | .059 (.026) | .062 (.026) |

| Gender | .005 (.023) | .001 (.022) | .007 (.022) |

| Qualification | .015 (.023) | .013 (.023) | .014 (.023) |

| Current Industry Experience | −.078 (.056) | −. 068 (.055) | −.070 (.055) |

| Past Experience | −.068 (.055) | −.066 (.055) | −.071 (.053) |

| R2 | .233 | .270 | .277 |

| R2 change | .037 | .007 | |

Note. N=656. Beta coefficients are reported in parentheses.

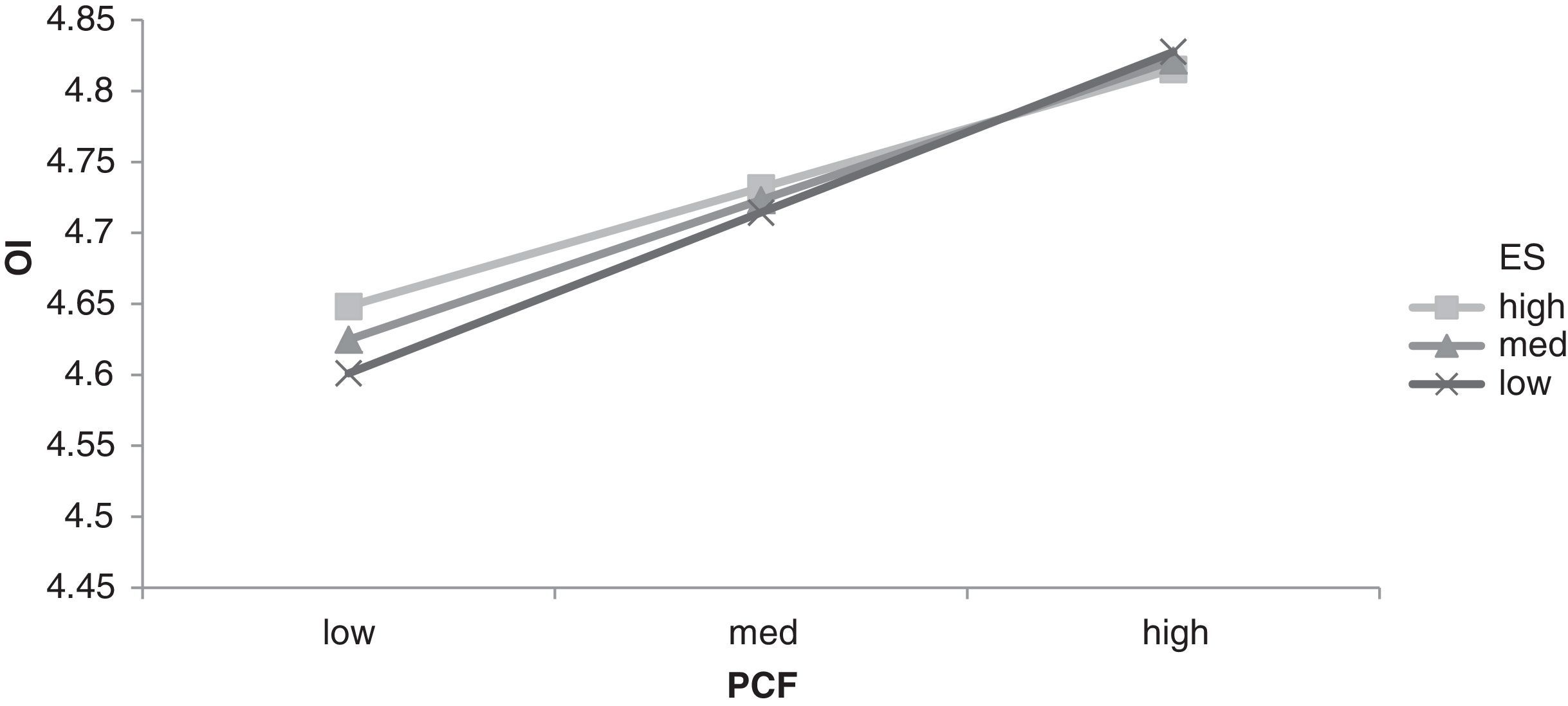

We plotted this interaction effect on a 3 x 3 mod graph (given in Figure 2), because individuals are divided into three different groups based on their level of equity sensitivity. Three crossing lines in Figure 2 indicate towards a significant interaction effect of psychological contract fulfillment and equity sensitivity on organizational identification. We can observe that the organizational identification of benevolent employees (low in equity sensitivity) is low at the lower level of psychological contract fulfillment while their organizational identification is high at the higher level of psychological contract fulfillment. On the other hand, the organizational identification of entitled employees (high in equity sensitivity) is high at the lower level of psychological contract fulfillment while it reduces at the higher level of psychological contract fulfillment. Similarly, the organizational identification of benevolent employees at the higher level of psychological contract fulfillment is lower than the equity sensitive but greater than the entitled. Overall, we have found that there is a significant interaction effect of psychological contract fulfillment and equity sensitivity on organizational identification. These results also supported Hypothesis 4 of the study.

Moderated Mediation AnalysisWe tested four conditions of moderated mediation (Muller, Judd, & Yzerbyt, 2005; Ng, Ang, & Chan, 2008) for testing moderated mediation hypotheses of the study. These four conditions of moderated mediation included: i) the effect of the mediator (psychological contract fulfillment) on the dependent variable (organizational identification) must be significant; ii) the interaction effect of the independent and moderator variables (psychological contract fulfillment and equity sensitivity) on the dependent variable (organizational identification) must be significant; iii) the effect of the independent variable (interpersonal and informational justice) on the dependent variable (organizational identification) must be significant; and iv) the indirect effect of the independent variable (interpersonal and informational justice) on the dependent variable (organizational identification) through the mediator (psychological contract fulfillment) must differ across different levels of the moderator (equity sensitivity). We have already tested first three conditions of moderated mediation in the previous section.

Finally, we examined the fourth condition of moderated mediation with the help of MODMED Macro by testing model 3 in SPSS (Preacher et al., 2007). We operationalized the value of the moderator at three different levels, i.e., medium (the mean), high (one standard deviation above the mean), and low (one standard deviation below the mean). Then, we assessed the indirect effect of interpersonal justice on organization identification via psychological contract fulfillment across each level of the moderator using 95% confidence intervals and 5,000 bootstrapping samples (Selig & Preacher, 2008). The results demonstrated that the indirect relationship of interpersonal justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment was significant across all levels of equity sensitivity. The upper bound and lower bound of bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals of the indirect effect on low equity sensitivity ranged from .0824 to .1619. The upper bound and lower bound of bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals for indirect effect on high equity sensitivity ranged from .0177 to .0739. The upper bound and the lower bound of bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals of the indirect effect on medium equity sensitivity ranged from .570 to .1159. Similarly, we found that the indirect effect of informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment was also significant across all levels of equity sensitivity. The upper bound and lower bound of bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals of the indirect effect of informational justice on low equity sensitivity ranged from .0778 to .1614. The upper bound and lower bound of bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals of the indirect effect on medium level of equity sensitivity ranged from .0095 to .0739. The upper bound and lower bound of bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals of the indirect effect on high level of equity sensitivity ranged from .0510 to .1102. Since the indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice was significant across all levels of equity sensitivity, Hypotheses 3a and 3b were not supported.

Overall, the results supported the positive association of interpersonal justice and informational justice with psychological contract fulfillment and organizational identification. We also found a positive association of psychological contract fulfillment with organizational identification. The study also found that the mediating role of psychological contract fulfillment in the relationship of interpersonal justice and informational justice with organizational identification was significant. The results further confirmed that the mediating role of psychological contract fulfillment did not vary across different levels of employee's equity sensitivity.

DiscussionThis study has contributed to the research stream of employment relationships through multiple ways. First, using the cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957), this study investigated the effect of two ignored sub-dimensions of organizational justice, i.e., interpersonal and informational justice on psychological contract of the employees. The statistical results of the study confirmed the hypotheses. Second, this study investigated the interrelationship between two subdimensions of POM framework following the recommendations of Masterson and Stamper (2003). This study tested the association between psychological contract fulfillment and organizational identification using the cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957). The statistical results of the study confirmed the positive association between psychological contract fulfillment and organizational identification. These findings are also consistent with the findings of some previous studies (De Ruiter, Lub, Jansma, & Blomme, 2016; Kreiner, 2002).

This study has also attempted to contribute in the research investigating the chain relationship of organizational justice, psychological contract fulfillment, and organizational identification. Particularly, we introduced psychological contract fulfillment as a mediator between interpersonal and informational justice and the organizational identification. Epitropaki (2013) found that the indirect effect of procedural justice on organizational identification through psychological contract breach was significant. We also found a significant indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment. Although the focus of the two studies is different in terms of breach and fulfillment, yet the significant direct effect of interpersonal and informational justice on psychological contract fulfillment and the significant indirect effect of interpersonal and informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment offer some important insights into the research and practice of employment relationships. Particularly, we stress that the fairness in interpersonal relations and information dissemination has also a sound effect on the employment relationship like the effect of fairness in carrying out organizational procedures. Based on the findings of our study, we agree with Epitropaki (2013) that the managers are organizational representatives who can maintain the employment relationships by establishing a fair interpersonal and informational relation with their subordinates. Particularly, the supervisors can prove themselves as good ‘guardians’ of the employment relationship by maintaining a fair environment characterized by informational and interpersonal justice. We focused on psychological contract fulfillment and found that the employees who perceive that their leaders are treating them fairly and providing fair detail about the organizational procedure and distribution of resources are more likely to develop their identification with their organization.

This study also found that equity sensitivity significantly moderates the relationship between psychological contract fulfillment and organizational identification. This confirms the view that equity sensitivity explains a manager's sensitivity to different fair and unfair situations that could affect their attitudes and behaviors (Huseman et al., 1985, 1987; King et al., 1993). Particularly, we found that the employment relationship weakens as the levels of equity sensitivity of the employee enhance. The employees who are highly sensitive to the fair and unfair situations are more likely to experience dissonance and inequity as compared to those low in equity sensitivity. Thus, the effect of the perceptions of psychological contract fulfillment on their identification was smaller. We expected that this indirect effect would be insignificant for the employees who are low in equity sensitivity. However, we found that the indirect effect of interpersonal justice as well as informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment remained significant for all groups of employees irrespective of their level of equity sensitivity. This finding stresses the importance of equity sensitivity of the employment relationship. Particularly, these findings communicate that the bondage between employee and employer is not affected by the level of equity sensitivity of the individuals.

Practical ImplicationsWe also found that the direct effect of interpersonal justice and informational justice on psychological contract fulfillment and organizational identification was stronger as compared to the informational justice. This implies that providing employees with fair explanations about organizational procedures could have a more profound effect on the employment relationship as compared to the interpersonal relations. For instance, Molinsky and Margolis (2006) reported that informational and interpersonal justice is effective in reducing the risks associated with organizational downsizing. However, the significant moderating role of equity sensitivity between psychological contract fulfillment and organizational identification implies that individual differences cannot be ignored to maintain an effective employment relationship with different individuals. The significant indirect effect of interpersonal justice as well as informational justice on organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment offers some interesting implications for the organizational managers. This result communicates the effect of individual differences on the employment relationship diminishes when organizational members attempt to maintain a justice climate through interpersonal and informational justice. Thus, the organizational managers need to ensure the organizational climate that encourages transparency and strong interpersonal relations between the supervisors and the subordinates.

The effective utilization of human resources has become challenging for employers in the recent economic crisis. At the same time, employees are consistently facing uncertainty regarding their job security. Those who survived remained under consistent fear of cut in their compensation and benefits despite their extra job responsibilities. This situation is severely affecting the employer-employee relationship. In this regard, researchers have been providing insights to practitioners in determining which factors are undermining employer-employee relationships. The literature on the relationship between procedural justice and psychological contract breach suggests that practitioners increase fairness of organizational procedures and policies. However, it is not possible for organizational members to revisit the procedures related with organizational resources (Fuchs & Edwards, 2012). This study suggests that practitioners can maintain employee perceptions of procedural injustice and psychological contract breach by maintaining a culture of interpersonal and informational justice. For instance, Molinsky and Margolis (2006) highlighted the importance of interpersonal and informational justice to reduce the risk of downsizing. The managers can also avoid various other organizational conflicts and reduce their costs by clearly communicating the employees about the lack of resources and by treating them with dignity and respect. Further, our study also provides practitioners with an insight into equity sensitivity, an individual characteristic that could severely affect employer-employee relationships by moderating the relationship between psychological contract fulfillment and organizational identification.

Limitations and Future ResearchThe first limitation of this study is that it is limited to one sector, namely the banking sector in Pakistan, and therefore the results of this study cannot be generalized. However, an opportunity exists for future research to replicate the current study in different countries and industry contexts. Secondly, the design of our study is non-experimental. Various authors, such as Stone-Romero and Rosopa (2008), have criticized that mediation cannot be tested in non-experimental designs. Thus, there is need to replicate the findings of this study with an experimental study. Third, we used single setting self-report measures to collect data, that could cause common method bias. Though we conducted a few tests to determine the extent of common method bias and did not found common method bias in the data, we suggest that other reported measures be used in future research. Similarly, psychological contract fulfillment involves expectations of both employer and employee; therefore such data must be collected in dyads from both parties.

Future research could use the scale by Robinson and Morrison (1995) that differentiates between transactional and relational psychological contract, instead of the global measure of psychological contract developed by Deery, Iverson, and Walsh (2006). Finally, we measured equity sensitivity as a uni-dimensional construct using the measure developed by Huseman et al. (1985). Taylor et al. (2009) contrasted the uni-dimensional measure of equity sensitivity with multidimensional measures and reported that multidimensional measure of equity sensitivity have greater capacity to represent the theoretical foundation of equity sensitivity.

It was also found that equity sensitivity does not moderate the indirect association of interpersonal and informational justice with organizational identification through psychological contract fulfillment. Thus, we suggest that researchers advance research on this study using a multidimensional measure of equity sensitivity. In a recent study, Foote and Harmon (2006) have differentiated between the construct of equity sensitivity and equity preference. We suggest researchers investigate the moderating role of equity preference in the indirect relationships explored in the current study.

Conflict of InterestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.