One of the most significant tasks of the psychiatrist in the emergency department is to predict the future suicide risk of each patient: if they determine that the risk is high, the patient will be admitted to the psychiatric unit, whilst if the risk is low, they will be discharged and sent home. In both cases, the underlying assumption is of accurate prediction, according to which the benefits outweigh the risks and justify the costs (the risks of further suicide attempts and death, in the first case; the possible damage derived from temporary loss of privacy, autonomy and social role, in the second1). The aim of this article is to quantify the probability that this assumption is unacceptable, in keeping with standard predictive precision (Table 1). To do this we will review the positive predictive values (PPV) of the different tests used in the prediction of death by suicide and then calculate their Clinical Utility Index (CUI+), an indicator which reflects the clinical usefulness of a test based on a standardized qualitative scale (Table 2).

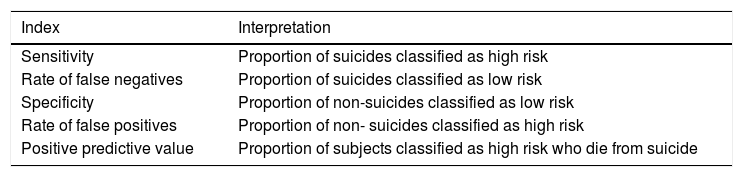

Diagnostic indications regularly used in the assessment of a diagnostic test applied to suicide prediction tests which reflect the precision of a test in absolute values.

| Index | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Proportion of suicides classified as high risk |

| Rate of false negatives | Proportion of suicides classified as low risk |

| Specificity | Proportion of non-suicides classified as low risk |

| Rate of false positives | Proportion of non- suicides classified as high risk |

| Positive predictive value | Proportion of subjects classified as high risk who die from suicide |

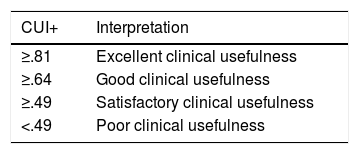

Interpretation of the Positive Clinical Utility Index (CUI+), indicator of the clinical usefulness of a predictive test based on a standardized qualitative scale.

| CUI+ | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| ≥.81 | Excellent clinical usefulness |

| ≥.64 | Good clinical usefulness |

| ≥.49 | Satisfactory clinical usefulness |

| <.49 | Poor clinical usefulness |

Estimated through the sensitivity product and the positive predictive value of the said test.6

The PPV is a useful indicator for assessing the precision of a predictive method — whether this be a psychometric scale or a clinical judgment, because it reflects the absolute number of correct assumptions for each 100 predictions made.2 A 20% PPV would therefore indicate that, out of every 100 patients assessed as high risk, 20 will die from suicide and 80 will not. The PPV depends on both the sensitivity and specificity of the test and the prevalence of the event to be predicted. Although a suicide risk prediction scale had a sensitivity and specificity of 99.99%, if it was used in a hypothetical population where the suicide rate was .00%, no patient classed as high risk would die from suicide (PPV 0%).

In 1954, A. Rosen showed that a major limitation when developing a method to predict suicide was precisely its low incidence, and therefore to overcome this obstacle it would be necessary to develop a test with extremely high precisión.3 It has recently been estimated that neither the combination of risk factors nor the scales based on psychological postulating obtain a PPV above 5.5%.2 Furthermore, a recently published study estimated that the PPV of different suicide prediction methods based on machine learning statistical modelling was not above 1.00% despite obtaining higher sensibilities and specificities than the traditional tests. The authors showed that the cause of the difficulty for reaching a higher PPV was the low rate of suicide.4

The ability of the emergency department psychiatrist to predict death by suicide, despite this being the most highly used method in daily practice, has rarely undergone research. In the only article to date it was estimated that the PPV of clinical judgment was 3.7% 6 months after the emergency department visit.5 To find out to what extent a predictive test is useful in clinical practice, the Positive Clinical Utility Index (CUI+), was calculated, which was the result of the sensitivity product by VPP. In this last case, even assuming a 100% sensitivity, the CUI+ would be .037 and would therefore be classified as poor clinical usefulness6 (Table 2).

These estimations suggest that at present we are unable to made a precise prediction of suicide,4 and, for that matter, any clinical decisions taken on the basis of considering a patient as high suicide risk would imply a margin of error. Assuming a PPV of 3.7%, 96.3% of patients classified as high risk would not die from suicide, and this constitutes poor clinical usefulness, even with a 100% sensitivity (CUI+ of .037).

From this viewpoint, the task of the emergency department psychiatrist would not be to predict suicide but to look for the most appropriate means of preventing it. Thus, when proposing psychiatric unit admission, they would take into consideration the potential benefit of hospitalisation over the overall patient status instead of solely basing judgment on autolytic risk calculation. If hospitalisation was considered to be counterproductive or unnecessary, an essential objective would be to promote outpatient follow-up because this is what has been demonstrated to be most effective in secondary prevention of suicide7 (all the more so because our environment involves psychopharmacological and/or psychotherapeutic treatment). As a result, instead of predicting a future suicide, the most important tasks of the emergency department psychiatrist could be forming crisis intervention, designing a Safety Plan,8 having the ability to offer an outpatient appointment in under 7 days9 and offering close contact through phone calls10 or other contact methods.

Please cite this article as: Hernández-Calle D, Martínez-Alés G, Román-Mazuecos E, Rodríguez-Vega B, Bravo-Ortiz MF. Prevención sobre predicción: el reto del psiquiatra en la valoración de riesgo autolítico en urgencias. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2020;13:232–233.