Schizophrenia and other non-affective psychoses are often disabling conditions that begin as early as adolescence and have an enormous impact on health and social systems. It is a public health priority to improve prevention of schizophrenic psychosis. A necessary step in this prevention would be to expand our limited knowledge of the causes of the psychosis, for which studying disease incidence is crucial: the epidemiological method typically generates causal hypotheses by comparing incidences in different populations, times, and places.1 Knowing the incidence of a disorder also allows health planning to be tailored to the needs of the population. However, identifying new cases of non-affective psychosis is a challenge: in many cases these are syndromes of insidious onset, with non-specific early manifestations that variably precede the development of the full picture, and whose symptoms may fluctuate, change, or disappear over time.

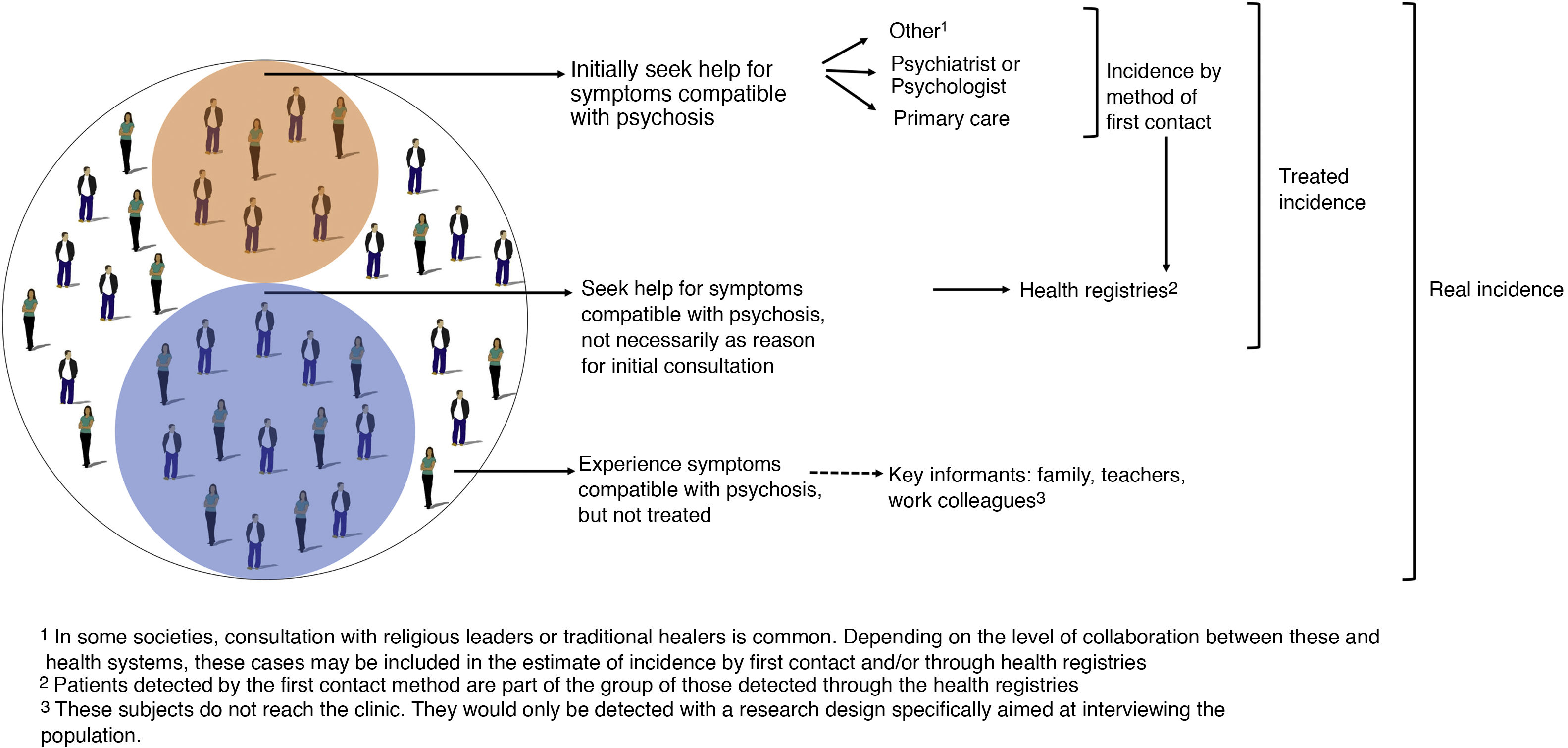

There are 2 main designs for studying the incidence of psychosis. On the one hand, first contact studies, developed from the 1970s onwards by the World Health Organisation in the framework of the Ten Country Study,2 are based on identifying people who contact health systems for the first time for reasons consistent with a psychotic disorder. On the other hand, analyses of health records, which are generally more sensitive,3 identify all people given a first diagnosis of non-affective psychosis in a space-time window (Fig. 1). These studies have revealed higher and more varied incidence rates of schizophrenia than was thought a few decades ago,4 rejecting the old belief in a constant global incidence.

No nationally representative study of the incidence of psychosis has been conducted to date in Spain. Some local studies have yielded heterogeneous results: a first contact study in Cantabria estimated 20 cases per 100,000 people aged 15–54 years per year,5 and another study using records from Barcelona found 51 cases for the same denominator.6 A recent European study has renewed interest in the subject by finding unusually low incidence rates in some areas of Spain (and Italy), compared to areas in more northern countries.7 Moreover, surprisingly, Jongsma et al. found no association between incidence of psychosis and population density in Spain, in contrast to studies in northern Europe8 that exposure to an urban environment increases and could double the risk of schizophrenia.

The causes of psychosis, like those of all disease, can act at different levels, both infra-individual – gene, neuron – and beyond the individual – at the level of neighbourhoods, societies – (Schwartz et al., 1999).9 For example, according to the paradigm that is currently most accepted, an urban environment would determine specific ways of interrelating, favouring processes of discrimination or interpersonal support involved in the onset of schizophrenia. The apparent discrepancies or exceptions recently identified in southern Europe raise questions that are also opportunities to broaden our understanding of the aetiology of psychosis. For example, is it plausible that, in Spain, the incidence of psychosis is not associated with the degree of urbanisation, or is this a design or measurement error? If this is a real finding, what sociological components of the 'urban environment' construct (discrimination or interpersonal support, social fragmentation, or cohesion, etc.) behave differently in Spain compared to other Western countries? In this regard, it is interesting to note that the association between the incidence of psychosis and urban environment has not been reported in countries of the global South, such as Brazil.10

There are now longitudinal electronic case registries in our country, as well as a myriad of socio-demographic, economic and cultural variables, which are measured both at the individual level and the ecological level, such as, for example, postcodes. By combining data from both sources, we will be able to propose and test hypotheses about the specific causal role played by urban planning and other ecological variables in the incidence of psychosis in Spain and other culturally proximate countries. We also believe that conducting incidence studies based on nationally representative clinical registries will enable health planning that is more appropriate to the real dimension of the problem and its impact on our communities.

FundingThis paper was possible thanks to a grant to rotate abroad, awarded to the first author by the Fundación Española de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental.

Please cite this article as: Romero-Pardo V, Mascayano F, Susser ES, Martínez-Alés G. Incidencia de esquizofrenia en España: más preguntas que certezas. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2022;15:61–62.