To develop a brief and reliable psychometric scale to identify individuals at risk for suicidal behaviour.

Method designCase–control study. Sample and setting: 182 individuals (61 suicide attempters, 57 psychiatric controls, and 64 psychiatrically healthy controls) aged 18 or older, admitted to the Emergency Department at Puerta de Hierro University Hospital in Madrid, Spain. Measures: All participants completed a form including their socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, and the Personality and Life Events scale (27 items). To assess Axis I diagnoses, all psychiatric patients (including suicide attempters) were administered the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Statistical analysis: Descriptive statistics were computed for the socio-demographic factors. Additionally, χ2 independence tests were applied to evaluate differences in socio-demographic and clinical variables, and the Personality and Life Events scale between groups. A stepwise linear regression with the backward variable selection was conducted to build the Short Personality Life Event (S-PLE) scale. In order to evaluate the accuracy, a ROC analysis was conducted. The internal reliability was assessed using Cronbach's α, and the external reliability was evaluated using a test–retest procedure.

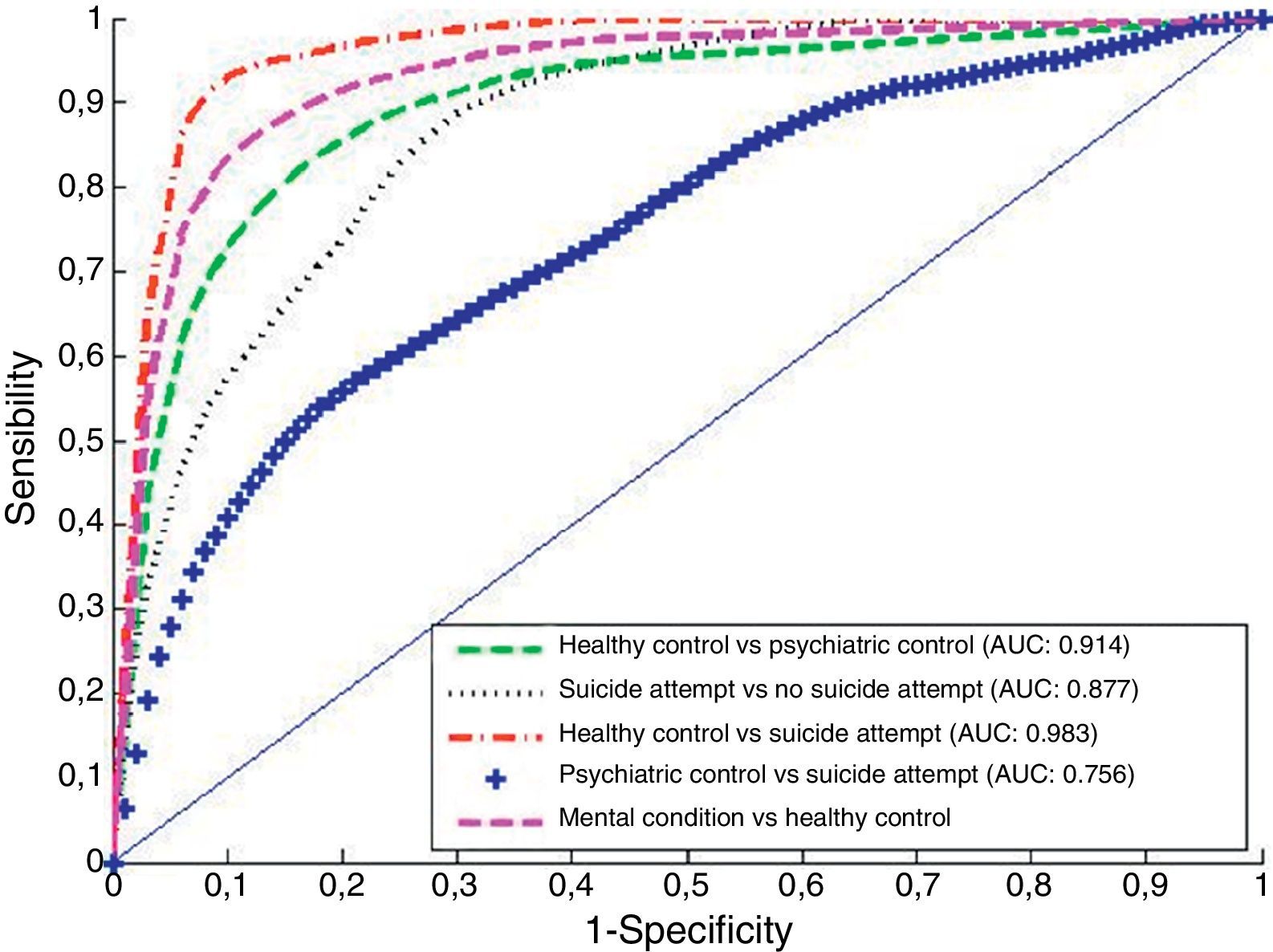

ResultsThe S-PLE scale, composed of just 6 items, showed good performance in discriminating between medical controls, psychiatric controls and suicide attempters in an independent sample. For instance, the S-PLE scale discriminated between past suicide and past non-suicide attempters with sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 75%. The area under the ROC curve was 88%. A factor analysis extracted only one factor, revealing a single dimension of the S-PLE scale. Furthermore, the S-PLE scale provides values of internal and external reliability between poor (test–retest: 0.55) and acceptable (Cronbach's α: 0.65) ranges. Administration time is about one minute.

ConclusionsThe S-PLE scale is a useful and accurate instrument for estimating the risk of suicidal behaviour in settings where the time is scarce.

Desarrollar una escala breve y fiable para identificar a las personas en riesgo de conducta suicida.

Método Diseñoestudio de caso-control. Muestra y centro: 182 individuos (61 personas que intentaron suicidarse, 57 controles psiquiátricos y 64 controles sanos) con una edad de 18 años o más, admitidos en la Unidad de Urgencias del Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro de Madrid, España. Mediciones: todos los participantes rellenaron un formulario que incluía sus características sociodemográficas y clínicas, y la Escala de Personalidad y Acontecimientos Vitales (27 cuestiones). Para evaluar los diagnósticos del Eje I, a todos los pacientes psiquiátricos (incluyendo a las personas que intentaron suicidarse) se les realizó la Entrevista Neuropsiquiátrica Internacional. Análisis estadístico: se aplicó estadística descriptiva para los factores sociodemográficos. Además, se aplicaron las pruebas de independencia de χ2 para evaluar las diferencias de las variables sociodemográficas y clínicas, y de la Escala de Personalidad y Acontecimientos Vitales entre grupos. Se llevó a cabo una regresión lineal escalonada con selección de variable retrospectiva para elaborar la escala abreviada de Personalidad y Acontecimientos Vitales (S-PLE). A fin de evaluar la precisión se realizó un análisis de ROC. Se evaluó la fiabilidad interna utilizando la α de Cronbach, y la fiabilidad externa mediante un procedimiento de prueba-reprueba.

ResultadosLa escala S-PLE, que se compone únicamente de 6 cuestiones, reflejó un buen desempeño al discriminar los controles sanos, los controles psiquiátricos y los intentos de suicidio en una muestra independiente. Por ejemplo, la escala S-PLE discriminó a las personas que intentaron suicidarse y a las que no lo hicieron en el pasado, con una sensibilidad del 80% y una especificidad del 75%. El área bajo la curva ROC fue del 88%. Un análisis factorial extrajo solamente un factor, lo que revela la dimensión única de la escala S-PLE. Además, la escala S-PLE aporta valores de fiabilidad interna y externa que se incluyen dentro de los rangos débil (prueba-reprueba: 0,55) y aceptable (α de Cronbach: 0,65). El tiempo de realización es de alrededor de un minuto.

ConclusionesLa escala S-PLE es un instrumento útil y preciso para calcular el riesgo de conducta suicida en centros asistenciales donde escasea el tiempo.

Suicide prevention is a major public health concern.1–3 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), suicide accounts approximately for 1.4% of the Global Burden of Disease.4 It is estimated that about 800,000 people will suicide each year, and at least 10–20 times more will make non-lethal attempts annually by the year 2020.5 Moreover, in the United States only, the annual estimated economic costs of suicide are about $33 billion per year.6

Despite these staggering figures, it is possible to partially prevent suicidal behaviour with specific interventions in high-risk populations.7,8 For instance, some investigators have pointed out that access to adequate treatment might reduce suicide rates up to 25%.9 More recently, Hampton10 reported a 75% reduction of suicide rates by implementing a depression care programme.

One of the most difficult tasks in preventing suicide is the detection of individuals at risk.11 Among the reasons behind this problem is the fact that most suicide attempters do not reveal their suicidal thoughts and plans to their physicians.12,13 Moreover, although several risk factors such as major depression,14 a previous suicide attempt,15 or recent life events16 increase the risk of suicide, previous efforts to find a tool that accurately identifies people at risk of suicidal behaviour have yet to yield good results.17,18 For instance, Bolton et al.19 conducted a study where the SAD PERSONS scale could not accurately predict suicide attempts among individuals requiring psychiatric services in emergency departments. In another study, the Suicide Intent Scale (SIS) was not able to predict which self-harming individuals would ultimately die by suicide.20

These findings highlight the importance of developing accurate tools to identify and prevent suicidal behaviour. With this aim, Blasco-Fontecilla et al.21 developed the Personality and Life Event (PLE) scale. The PLE scale consists of 27 of the most discriminative items from a collection of questionnaires usually employed in the assessment of suicidal behaviour. The 27 items were selected using the Lars-en algorithm.22 The PLE scale showed excellent accuracy (86.4%), sensitivity (80.8%), and specificity (89.6%) in classifying suicide attempters.21

The aim of this article is to develop and test a shorter version of the PLE scale that can be used in setups where time is scarce such as emergency departments and overloaded outpatient clinics. Moreover, the development of this short scale is also relevant because of the increase of online e-health applications: nowadays, both researchers and practitioners collect patient's data by means of mobile phone applications.23 The availability of short scales is vital considering that attrition is one of the main problems faced when collecting this type of data.24 Our hypothesis is that a shorter version of the PLE scale can accurately identify individuals at risk for suicidal behaviour.

Materials and methodsSamples and procedureParticipants received no incentives. Initially, we recruited 236 individuals, but 54 (22.5%) were excluded from our analyses because they had missing values. The final sample in this study consisted of 182 individuals (61 suicide attempters, 57 psychiatric controls, and 64 psychiatrically healthy controls) aged 18 or older, admitted to the emergency department at Puerta de Hierro University Hospital in Madrid, Spain, between 1st of June and 1st of December, 2013. All participants were evaluated within the first 24h after admission. The assessments were made by residents in psychiatry with specific training to evaluate suicide attempts.

The suicide attempter group comprised 18 men and 43 women. The psychiatric controls were 21 men and 36 women presenting to the emergency department for any psychiatric reason other than suicidal behaviour. These individuals denied a history of previous suicidal attempts. The psychiatrically healthy controls (henceforth referred to simply as medical controls) were 26 men and 38 women, presenting to the emergency department because of a medical (non-psychiatric) reason. Medical controls were free of psychiatric conditions. In all three groups, individuals who were unable to decide or understand the PLE scale for any reason were excluded. All included patients provided written informed consent to take part in the study. The Puerta de Hierro University Hospital Ethics Committee approved the study.

MeasuresAll participants completed a form including their socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. In order to facilitate the use of the PLE scale, all the items were dichotomized (yes/no). To assess Axis I diagnoses, all psychiatric patients (including suicide attempters) were administered the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).25 The MINI is an efficient, short, and easy to administrate structured diagnostic interview.21,25 Medical controls were determined not to have a personal history of psychiatric illnesses, as verified by direct questioning and review of the electronic medical record.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were computed for the socio-demographic factors. Additionally, Chi-square independence tests were applied to evaluate differences in socio-demographic and clinical variables between groups. The Chi-square independence test was also conducted to assess the strength of the relationship between each item in the PLE scale and the type of individual (suicide attempter, psychiatric control or medical control).

A stepwise linear regression with backward variable selection was conducted to build the short version of the PLE scale. In order to evaluate the accuracy of the developed scale, a ROC analysis was conducted. Typically, works published in the areas of psychology and psychiatry conduct this type of analysis using the same data set for both, estimation of the parameters of the classifiers and accuracy assessment. The consequence of this practice is that the reported results tend to be better than what is observed in practice. For example, Support Vector Machines are capable of attaining a perfect classification in a given set. However, whenever this classifier is applied to a different data set, its performance decreases dramatically. This phenomenon is known as overfitting. In order to avoid this problem, the current ROC analysis is performed according to the usual practice in the pattern recognition community, i.e., the data are separated in two disjoint sets, namely, training and test sets. The training set is used to estimate the parameters of the linear regression, and the test set is used to calculate the ROC curves. With the aim of obtaining more relevant results, 100 cross-validations were conducted. In each cross-validation, the training set was composed by 32 medical controls, 29 psychiatric controls, and 31 suicide attempters randomly selected from our database. The remaining individuals (32 medical controls, 28 psychiatric controls, and 30 suicide attempters) were used as the test set.

Finally, after the performance of the proposed scale was assessed, a factor analysis with varimax rotation was performed, and the internal and external reliability were computed in order to elucidate the psychometric properties of the proposed scale. The internal reliability was assessed using Cronbach's α, and the external reliability was evaluated using a test–retest procedure, and the intraclass correlation coefficient. The interval for the test–retests ranged between three and six months. Basically, between 3 and 6 months after the initial interview, all participants were contacted by telephone, and asked to answer the PLE scale again. Due to refusal to participate in the retest, impossibility to contact the individual, or scarce time since the first interview (less than three months scheduled), we used a subsample of 85 individuals (47%) to make the test–retest analyses.

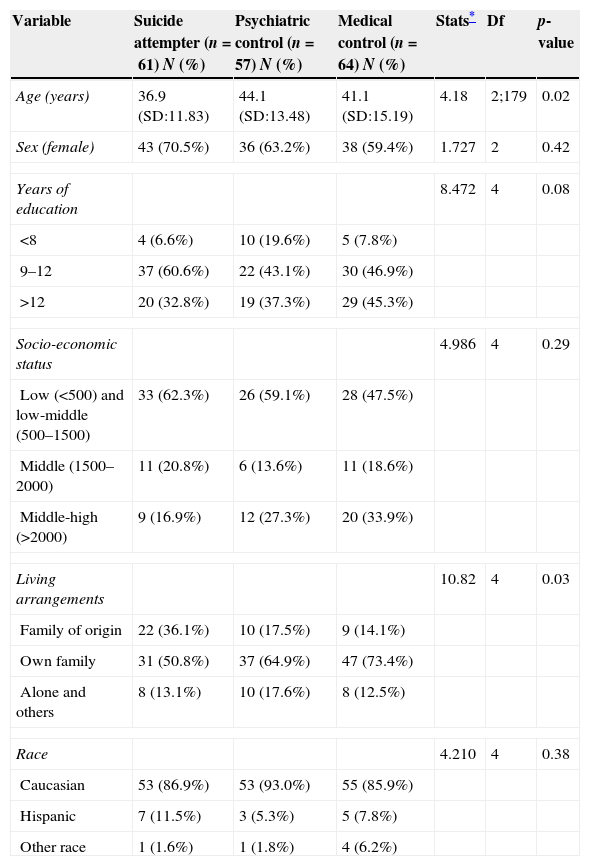

ResultsSample characteristicsTable 1 shows the socio-demographic data. Apart from age and living arrangements, there no statistically significant differences between groups in terms of socio-demographics.

Comparison of suicide attempters (n=61), psychiatric controls (n=57), and medical controls (n=64) on socio-demographic variables.

| Variable | Suicide attempter (n=61) N (%) | Psychiatric control (n=57) N (%) | Medical control (n=64) N (%) | Stats* | Df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.9 (SD:11.83) | 44.1 (SD:13.48) | 41.1 (SD:15.19) | 4.18 | 2;179 | 0.02 |

| Sex (female) | 43 (70.5%) | 36 (63.2%) | 38 (59.4%) | 1.727 | 2 | 0.42 |

| Years of education | 8.472 | 4 | 0.08 | |||

| <8 | 4 (6.6%) | 10 (19.6%) | 5 (7.8%) | |||

| 9–12 | 37 (60.6%) | 22 (43.1%) | 30 (46.9%) | |||

| >12 | 20 (32.8%) | 19 (37.3%) | 29 (45.3%) | |||

| Socio-economic status | 4.986 | 4 | 0.29 | |||

| Low (<500) and low-middle (500–1500) | 33 (62.3%) | 26 (59.1%) | 28 (47.5%) | |||

| Middle (1500–2000) | 11 (20.8%) | 6 (13.6%) | 11 (18.6%) | |||

| Middle-high (>2000) | 9 (16.9%) | 12 (27.3%) | 20 (33.9%) | |||

| Living arrangements | 10.82 | 4 | 0.03 | |||

| Family of origin | 22 (36.1%) | 10 (17.5%) | 9 (14.1%) | |||

| Own family | 31 (50.8%) | 37 (64.9%) | 47 (73.4%) | |||

| Alone and others | 8 (13.1%) | 10 (17.6%) | 8 (12.5%) | |||

| Race | 4.210 | 4 | 0.38 | |||

| Caucasian | 53 (86.9%) | 53 (93.0%) | 55 (85.9%) | |||

| Hispanic | 7 (11.5%) | 3 (5.3%) | 5 (7.8%) | |||

| Other race | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (1.8%) | 4 (6.2%) | |||

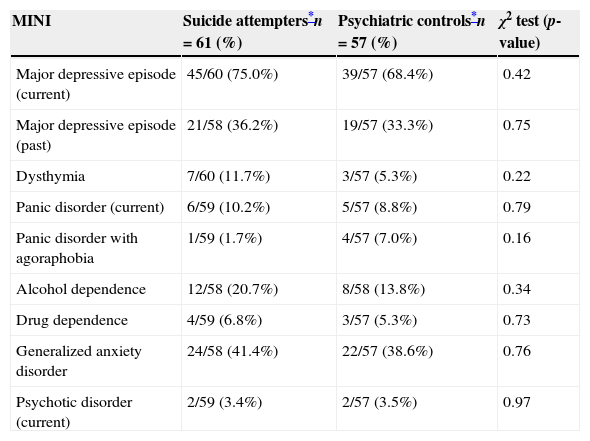

Table 2 shows the comparison between the scores obtained by the suicidal attempters and the psychiatric controls in the MINI scale. There were no statistically significant differences in Axis I disorders when comparing suicide attempters and psychiatric controls.

Comparison of suicide attempters and psychiatric controls on psychiatric disorders (MINI scale).

| MINI | Suicide attempters*n=61 (%) | Psychiatric controls*n=57 (%) | χ2 test (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major depressive episode (current) | 45/60 (75.0%) | 39/57 (68.4%) | 0.42 |

| Major depressive episode (past) | 21/58 (36.2%) | 19/57 (33.3%) | 0.75 |

| Dysthymia | 7/60 (11.7%) | 3/57 (5.3%) | 0.22 |

| Panic disorder (current) | 6/59 (10.2%) | 5/57 (8.8%) | 0.79 |

| Panic disorder with agoraphobia | 1/59 (1.7%) | 4/57 (7.0%) | 0.16 |

| Alcohol dependence | 12/58 (20.7%) | 8/58 (13.8%) | 0.34 |

| Drug dependence | 4/59 (6.8%) | 3/57 (5.3%) | 0.73 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 24/58 (41.4%) | 22/57 (38.6%) | 0.76 |

| Psychotic disorder (current) | 2/59 (3.4%) | 2/57 (3.5%) | 0.97 |

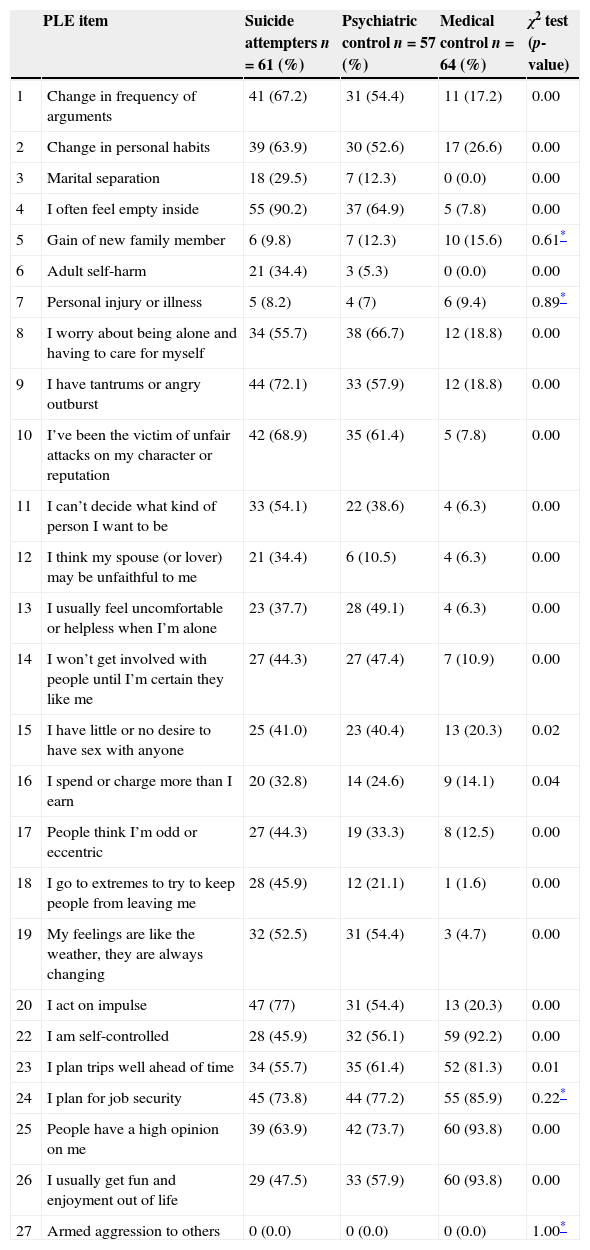

A Chi-square test assessed the relationship between each item and group membership (see Table 3).

Comparison of suicide attempters (n=61), psychiatric controls (n=57), and medical controls (n=64) on the items of the PLE scale.

| PLE item | Suicide attempters n=61 (%) | Psychiatric control n=57 (%) | Medical control n=64 (%) | χ2 test (p-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Change in frequency of arguments | 41 (67.2) | 31 (54.4) | 11 (17.2) | 0.00 |

| 2 | Change in personal habits | 39 (63.9) | 30 (52.6) | 17 (26.6) | 0.00 |

| 3 | Marital separation | 18 (29.5) | 7 (12.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.00 |

| 4 | I often feel empty inside | 55 (90.2) | 37 (64.9) | 5 (7.8) | 0.00 |

| 5 | Gain of new family member | 6 (9.8) | 7 (12.3) | 10 (15.6) | 0.61* |

| 6 | Adult self-harm | 21 (34.4) | 3 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.00 |

| 7 | Personal injury or illness | 5 (8.2) | 4 (7) | 6 (9.4) | 0.89* |

| 8 | I worry about being alone and having to care for myself | 34 (55.7) | 38 (66.7) | 12 (18.8) | 0.00 |

| 9 | I have tantrums or angry outburst | 44 (72.1) | 33 (57.9) | 12 (18.8) | 0.00 |

| 10 | I’ve been the victim of unfair attacks on my character or reputation | 42 (68.9) | 35 (61.4) | 5 (7.8) | 0.00 |

| 11 | I can’t decide what kind of person I want to be | 33 (54.1) | 22 (38.6) | 4 (6.3) | 0.00 |

| 12 | I think my spouse (or lover) may be unfaithful to me | 21 (34.4) | 6 (10.5) | 4 (6.3) | 0.00 |

| 13 | I usually feel uncomfortable or helpless when I’m alone | 23 (37.7) | 28 (49.1) | 4 (6.3) | 0.00 |

| 14 | I won’t get involved with people until I’m certain they like me | 27 (44.3) | 27 (47.4) | 7 (10.9) | 0.00 |

| 15 | I have little or no desire to have sex with anyone | 25 (41.0) | 23 (40.4) | 13 (20.3) | 0.02 |

| 16 | I spend or charge more than I earn | 20 (32.8) | 14 (24.6) | 9 (14.1) | 0.04 |

| 17 | People think I’m odd or eccentric | 27 (44.3) | 19 (33.3) | 8 (12.5) | 0.00 |

| 18 | I go to extremes to try to keep people from leaving me | 28 (45.9) | 12 (21.1) | 1 (1.6) | 0.00 |

| 19 | My feelings are like the weather, they are always changing | 32 (52.5) | 31 (54.4) | 3 (4.7) | 0.00 |

| 20 | I act on impulse | 47 (77) | 31 (54.4) | 13 (20.3) | 0.00 |

| 22 | I am self-controlled | 28 (45.9) | 32 (56.1) | 59 (92.2) | 0.00 |

| 23 | I plan trips well ahead of time | 34 (55.7) | 35 (61.4) | 52 (81.3) | 0.01 |

| 24 | I plan for job security | 45 (73.8) | 44 (77.2) | 55 (85.9) | 0.22* |

| 25 | People have a high opinion on me | 39 (63.9) | 42 (73.7) | 60 (93.8) | 0.00 |

| 26 | I usually get fun and enjoyment out of life | 29 (47.5) | 33 (57.9) | 60 (93.8) | 0.00 |

| 27 | Armed aggression to others | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00* |

The items “Gain of a New Family Member”, “Personal Injury or Illness”, “I Plan for Job Security” or “Armed Aggression to Others” were not related to suicide attempter status. Similarly, “I Have Little or No Desire to have sex with Anyone” and “I Spend or Charge More that I Earn” showed a weak relation to suicide attempter status. These results support the idea of shortening the PLE scale.

Stepwise backward item selectionA stepwise backward regression analysis was conducted to select the most suitable items to be included in the S-PLE scale. The result of this analysis was the selection of the following six items: “I often feel empty inside”, “Adult self harm”, “I have tantrums or angry outbursts”, “I have been the victim of unfair attacks on my character or reputation”, “I can’t decide what kind of person I want to be”, and “I think my spouse (or lover) may be unfaithful to me”.

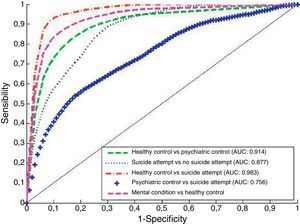

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysisOnce the relevant items were identified, a ROC analysis evaluated its capacity to correctly classify the individuals. The corresponding results are shown in Fig. 1. This figure shows the average ROCs for the 100 simulations mentioned above, together with their average area under the curve (AUC). The proposed scale accurately discriminated medical controls from psychiatric controls (dashed line), achieving a sensitivity of nearly 90% with a specificity of 75%. Thus, the S-PLE scale could be used as a good instrument for screening mental diseases in primary care settings.

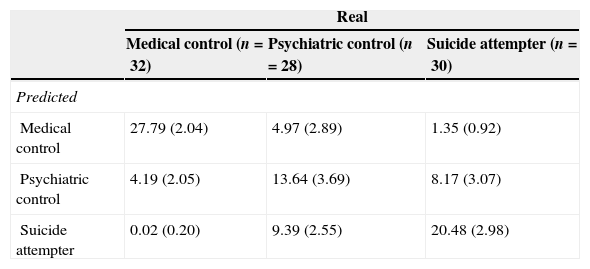

Depending on the type of Service (emergency department, walk-in clinics, and so on) the predictive parameters (i.e., sensitivity, specificity) could be assigned different values. For instance, a medical centre that fixes thresholds of 90% sensitivity in discriminating between medical and psychiatric controls, and of 70% specificity in discriminating between psychiatric controls and suicide attempters, will obtain the Confusion matrix shown in Table 4.

Confusion matrix.a

| Real | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical control (n=32) | Psychiatric control (n=28) | Suicide attempter (n=30) | |

| Predicted | |||

| Medical control | 27.79 (2.04) | 4.97 (2.89) | 1.35 (0.92) |

| Psychiatric control | 4.19 (2.05) | 13.64 (3.69) | 8.17 (3.07) |

| Suicide attempter | 0.02 (0.20) | 9.39 (2.55) | 20.48 (2.98) |

Mean and standard deviation of the number of cases in each cell over 100 simulations.

The performance of a given classification model can be evaluated by a confusion matrix. The confusion matrix displays the accuracy of the predictions made by the model. Thus, the diagonal displays the number of correct classifications made for each class (i.e., suicide attempters, psychiatric controls, or medical controls), and the off diagonal shows the errors made. For instance, of the 32 test medical controls, nearly 28 (27.79) were correctly classified as medical controls, and about four (4.19) and 0 (0.02) individuals were incorrectly classified as psychiatric controls and suicide attempters, respectively.

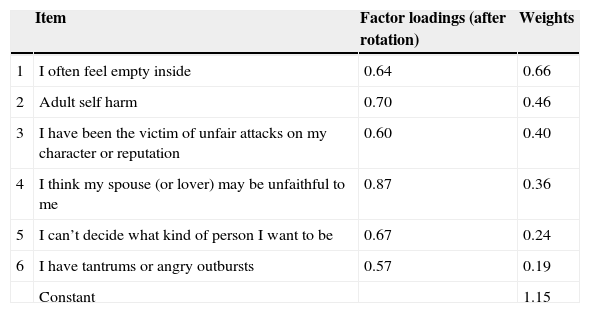

A factor analysis with varimax rotation, applied on the selected items, extracted only one factor. This reflects the one-dimensionality of the S-PLE scale. The extracted factor (with eigenvalue higher than one) explained 36.9% of the variance. The first columns of Table 5 show the factor loadings after rotation. The contribution of the selected items to this factor is very similar.

Factor analysis and weights of the S-PLE scale.

| Item | Factor loadings (after rotation) | Weights | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I often feel empty inside | 0.64 | 0.66 |

| 2 | Adult self harm | 0.70 | 0.46 |

| 3 | I have been the victim of unfair attacks on my character or reputation | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| 4 | I think my spouse (or lover) may be unfaithful to me | 0.87 | 0.36 |

| 5 | I can’t decide what kind of person I want to be | 0.67 | 0.24 |

| 6 | I have tantrums or angry outbursts | 0.57 | 0.19 |

| Constant | 1.15 |

Regarding internal consistency, the Cronbach's α was 0.65, whereas the test–retest reliability was 0.55 (calculated based on data from 85 individuals who participated in the retest), and the intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.53.

Proposed scaleFinally, the weights of the proposed scale were calculated using the full data set. These weights are shown in the last column of Table 5. The total score on the S-PLE scale for a given individual is obtained by summing the weights of the items that he/she answered affirmatively plus the constant. For instance, an individual who feels “often empty inside”, and has a history of “adult self-harm” would score 2.27 [0.66 (emptiness)+0.46 (adult self-harm)+1.15 (constant)] (see Table 5 for weights).

Two thresholds are suggested to differentiate between the three types of individuals. Individuals with a score lower than 1.70 are considered mentally healthy; individuals with a score above 2.46 are considered at risk for attempting suicide; finally, individuals with scores between these two values are classified as individuals with a possible mental disorder. The values assigned to these thresholds are those that maximize the classification accuracy.

DiscussionWe report on the development and testing of a Short Personality Event (S-PLE) scale. The S-PLE scale was demonstrated to be a reliable instrument for classifying individuals as past suicide attempters or not. Our results have also shown that the S-PLE scale was able to distinguish between individuals with mental conditions – either psychiatric controls or suicide attempters – and psychiatrically healthy controls. The performance of the S-PLE scale decreases when it comes to separating psychiatric controls from suicide attempters. This is not surprising given that psychiatric diagnoses are per se risk factors for suicidal behaviour. In any case, the AUC of the ROC curve comparing psychiatric controls and suicide attempters was still fairly acceptable (0.756). The study was completed with an assessment of the internal and external reliability. In this assessment the Cronbach's α took a value of 0.65, a value which is close to the benchmark suggested by Nunnaly in 1978.26 Regarding the external reliability, the test–retest correlation was 0.55. This low correlation was expected, as some of the items included in the S-PLE scale (e.g., “I have tantrums or angry outbursts”) measure the individual's state, not an individual's trait. Moreover, the fact that only six items compose this scale makes it particularly useful in settings where time is scarce.

Another major strength of the S-PLE scale is that it may indirectly evaluate the risk of suicidal behaviour. The items composing the S-PLE scale assess the way the examinee feels with respect to both himself and his social, work and emotional environment. This is important because most suicide attempters and completers do not display suicidal ideation in the previous appointments with their physicians,12 thus hampering the prevention of suicidal behaviour. Fear of stigma, hospitalization or truncation of their plans could explain that lack of communication.12,13 In this context, the S-PLE might be particularly interesting, as with the exception of adult self-harm, the S-PLE has no direct questions about suicide attempt. Accordingly, the S-PLE could be particularly useful for patients who might want to hide this information. In other words, this tool allows the clinician to identify those at risk circumventing reliance on patient reports of suicidal ideation.

Six items related to personality dysfunction, and a history of previous self-harm compose the S-PLE scale. The most discriminative items were “I often feel empty inside” and “Adult self-harm”. These results are in keeping with the literature. For instance, in a recent review, we found that emptiness might have more predictive power than impulsiveness in the prediction of suicidal behaviour, and could be one of the clinical factors most closely associated with suicide attempt repetition,27–29 and the addiction to suicidal behaviour.29,30 Furthermore, a history of self-harm and affective instability are well-recognized risk factors for suicidal behaviour.31,32

A limitation of the present study is that the resulting set of 6 items has yet to be compared to specific scales that assess risk of suicidal behaviour. As well, the S-PLE has not yet been tested prospectively. Nonetheless, the S-PLE ability to identify those likely to have a psychiatric condition and those likely to have a past suicide attempt in about one minute has utility.

ConclusionsThe S-PLE scale has shown acceptable psychometric properties, and is a valuable screening instrument in the assessment of risk of suicidal behaviour. The S-PLE scale brings together two important characteristics: it indirectly measures suicide risk, and can be easily answered within a very short time period. Thus, the S-PLE scale might be an interesting tool in primary or emergency care settings.

FundingThis article received support from the CIBERSAM (Banco de Instrumentos del CIBERSAM; http://www.cibersam.es/cibersam) to develop a scale capable of predicting suicidal behaviours (the Personality and Life Events Scale, PLE). The S-PLE will be included into the “Banco de Instrumentos” of the CIBERSAM. Paula Artieda-Urrutia has obtained competitive funding from the IDIPHIM (http://www.investigacionpuertadehierro.com/).

Conflict of interestIn the last three years, Dr. Hilario Blasco-Fontecilla has received lecture fees from Eli Lilly, AB-Biotics, Janssen, Rovi, and Shire. Maria A. Oquendo received royalties for the commercial use of the C-SSRS and her family owns stock in Bristol Myers Squibb. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

Monica Fernández-Rodriguez, Isabel González-Villalobos, Cesar Rodriguez-Lomas, Maria Martin-Garcia, and Rocio Blanco-Fernández helped us in recruiting some individuals for this study. Dr. Iruela-Cuadrado allowed us to carry out this study at Puerta de Hierro University Hospital.

Please cite this article as: Artieda-Urrutia P, Delgado-Gómez D, Ruiz-Hernández D, García-Vega JM, Berenguer N, Oquendo MA, et al. Escala Abreviada de Personalidad y Acontecimientos Vitales para la detección de los intentos de suicidio. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2015;8:199–206.