Corporate Social Responsibility has emerged as a response to the increasing demand of societies to have more responsible, ethical, transparent and respectable public and private organizations. However, these corporate strategies cannot be a reality without a parallel evolution on individual responsible behaviors, aligned with the claimed premises and values that are gaining space in the social and economic fields. Although literature on consumer behavior has correctly addressed new tendencies of ethical consumption during the last decades, citizens should be responsible not only of their purchasing choices, but also of the influence that their daily acts and decisions will have on the economic, social and environmental spheres of life. This article introduces Personal Social Responsibility as a new concept, based on the concepts of Corporate and Consumer Social Responsibility, providing a theoretical framework as a starting point for future empirical research.

La responsabilidad social corporativa ha surgido como respuesta a la demanda creciente de las empresas de contar con organizaciones públicas y privadas más responsables, éticas, transparentes y respetables. Sin embargo, estas estrategias corporativas no pueden constituir una realidad sin una evolución paralela de los comportamientos individuales responsables, en línea con las premisas y valores reivindicados que van ganando espacio en los ámbitos sociales y económicos. Aunque la literatura sobre el comportamiento del consumidor ha abordado con corrección las nuevas tendencias del consumo ético durante las últimas décadas, los ciudadanos deberían ser responsables, no sólo de sus elecciones sobre compras, sino también de la influencia que tendrán sus acciones y decisiones diarias en las esferas económicas, sociales y ambientales de la vida. Este artículo introduce la responsabilidad social personal como nuevo concepto, basado en los conceptos de la responsabilidad social corporativa, y aportando un marco teórico como punto de partida para la investigación empírica futura.

Introducing Personal Social Responsibility as a key element to upgrade CSR

IntroductionA recent national survey to one thousand citizens in Spain concludes that a 49% of the respondents are critical consumers, excluding or boycotting those brands believed to be irresponsible (Fundación Adecco, 2015). This study indicates that citizens are placed as the third group of importance in responsibility toward society, satisfying the environment needs and contributing to the end of the crisis, just behind the government and the enterprises. This perception of the responsibility that citizens have in the development of a sustainable society is not independent from the corporate system, and contributes to their synchronic evolution.

The economic and financial crisis, the crisis of developed societies, the policy crisis and the crisis of values have led to an individual, organizational and global analysis of the human being as a citizen of a globalized world. People are beginning to know, to get informed, to be interested on and to question how the system works – maybe in an attempt to point out the culprit (Deng, 2012). All this information has contributed to a general and increasing demand of more responsible, ethical, transparent and respectable organizations. But, what about us? What about our personal behavior as consumers, citizens, workers, neighbors or members of a certain family or community?

Literature on consumer behavior has correctly addressed new tendencies of ethical consumption during the last decades, which have been analyzed upon different perspectives such as social, ethical, responsible, conscious, and sustainable (Vitell, 2015). However, individuals are not only consumers and behavior has exceeded the limits of a mere economic exchange and consumption. Citizens should be responsible not only of their purchasing choices, but also of the influence that their daily acts and decisions will have on the economic, social and environmental spheres of life. Taking the car to go to our job or the public transport, the bicycle or just walking; buying what we desire in a certain point of time or just what we need; downloading films from the Internet for a Friday night or, instead, renting it in a video store; acting as a constant example for our children, families and friends; dedicating one or two hours a week of our spare time to help a social organization of our community, are some examples of decisions that will make the difference on the impacts – and the results of the impacts – that our way of life will have on the evolution of the world.

All these reasons lead us to talk about Personal Social Responsibility (PSR) as a new construct that not only incorporates what previous works have accepted within the field of ethical or responsible consumption, but also that is determined by different dimensions of behavior related to further issues not considered by them.

The main contribution of this paper is to define and justify, conducting a qualitative research (in-depth interviews and a group discussion), the concept of Personal Social Responsibility (PSR). To accomplish this goal, in the following sections a theoretical framework of Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR) and CSR is presented. While the present research focused on PSR, future research can examine the relationship between PSR and the level of CSR of the companies of a country or area, as well the relationship with the level of education or general development.

We draw on extant research in marketing and consumer behavior to propose the nature and dimensions of Personal Social Responsibility (PSR). More specifically, we first review the extant literature regarding responsible, socially responsible, green, ethical and social consumption behavior. Then, we provide a brief introduction to the main contributions on the literature of CSR, focusing on a particular model that can be related to the consumer perspective of social responsibility. With those arguments, we proceed to specifically address the proposed construct of Personal Social Responsibility. The article is concluded with a discussion of the main theoretical propositions developed and their managerial implications, as well as an outline of a further research agenda in the area of consumer behavior.

MethodologyThe methodology followed for the specification of the domain of the construct consisted in two parts: the first one was the literature review, and the second part the use of qualitative methods (in-depth interviews and a group discussion), which are explained and detailed in the next sections.

After the literature review on Consumer and Corporate Social responsibility (Section “Developing Personal Social Responsibility on the basis of Consumer and Corporate Social Responsibility”), in-depth interviews to four researchers and a focus group interview (with 6 members) to a convenience sample of consumers were conducted, in order to (1) help in the process of defining the construct and dimensionality of PSR, and (2) help on the translation of the dimensions identified in the literature from the consumer and corporate perspectives to the personal field of action (Section “Personal Social Responsibility”).

Each of the in-depth interviews lasted between 30 and 45minutes, and the focus group one hour and a half. In all of them initial questions were related to what behaviors of the participants or others they believed to be considered as “personal social responsibility towards society” (i.e., local purchasing, helping others, the use of public transport, environmental criteria or anti-consumption patterns, among others). Next, they were requested to focus specifically on individual behaviors related to each of the dimensions identified in the literature review, which had been also mentioned during the interviews. Then, they were asked to briefly define what Personal Social Responsibility meant for them and summarized the core idea of the construct.

In what follows, we proceed to specify the conceptual background on which PSR has been developed, that is Consumer and Corporate Social Responsibility. Then, based on this literature review and the results of the qualitative research conducted, the construct is presented and defined, followed by a discussion of its academic and managerial implications.

Developing personal social responsibility on the basis of consumer and corporate social responsibilityCitizens have a fundamental tool for social change at our disposal: consumption. As consumers and savers, we have the opportunity to use our decision judgment according to our convictions and therefore promote, through our purchasing and investment patterns, the construction of a sustainable development.1 It's been conceived by the simple, positive activism of casting our economic vote conscientiously (Hollister et al., 1994). Just as Melé (2009) points out:

“Taking into account that we are all the market system, if we all change our way of thinking, being, acting and investing our money, the operation and direction that is taking the economic model will change. This is not utopian. The State, the banking and the industry move at the request of the money managed by the individuals, the citizens, the community. Therefore, the power of the citizen does not lie in his/her vote, but in the direction in which his/her money is being directed, his/her way of consuming”2 (Melé, 2009:43).

A new hope of change is emerging in some groups of consumers that find in their purchase decisions a way of economic power that can control or, at least, have an impact on the way corporations behave. This perspective, that takes into account the influence and power of consumer decisions on the direction that will guide the evolution of societies, is the one considered in the main contributions of responsible, green or ethical behavior (Antil and Bennet, 1979; Antil, 1984; Ha-Brookshire & Hodges, 2009; Mohr, Webb, & Harris, 2001; Roberts, 1995; Uusitalo & Oksanen, 2004; Vitell, 2015; Webster, 1975).

In this sense, a deep look at the existing literature on consumer responsible behavior and the dimensions composing this construct sheds light to one fundamental conclusion: there is an excessive focus on particular matters related to consumption patterns and its relation to corporate performance and, on the other hand, there is a need to embrace further issues within the concept that involve different fields of an individual's everyday life. Indeed, some authors have pointed to the need of updating the measures (Webb, Mohr, & Harris, 2008) and the definitions in response to a full range of social issues, that conceptually incorporate the parallelism on the evolution that consumers and corporations are undergoing and, additionally, include other issues that are not directly related to consumer behavior but that can be complementary – since consumption can have an influence on other fields of everyday life and society and vice versa.

Therefore, we propose that Personal Social Responsibility (PSR) should perform the daily life behavior of the individual, as a member of the society – and not only as a consumer – basing his/her decisions to generate positive impacts on his/her social, environmental and economic environment. Our conception of PSR is aligned with the one that determines CSR patterns. As CSR describes the relationship between business and the larger society (Snider, Hill, and Martin et al., 2003), PSR should describe the individual's behavior toward and the effects on his/her social and ecological environment through his/her daily decisions. That means that similarly to what happens with companies, that pursue better relationships with their stakeholders through their responsible behaviors (Sen, Bhattacharya, & Korschun, 2006), individuals’ decisions will be also based on seeking greater relationships with their stakeholders – in this case families, friends, colleagues or the community.

All the definitions provided in the next sections refer to consumers in their role as part of a society, of an environment that influences them or that is influenced by their purchasing decisions. In fact, considering different dimensions of consumer behavior in addition to the direct outcomes of his/her purchase decisions, such as the utility maximization or the economic performance, is parallel to the concept of CSR. Indeed, it appears to have a greater sense to consider a corporate view when analyzing individual social responsibilities due to their close relation. As Deviney et al. (2010:35) point out, “social consumerism is one that is embodied within and embodies general notions of corporate and consumer behavior coevolving to create, characterize, and police a marketplace”. In addition to that, the authors believe that social consumption is not something driven by the fundamental beliefs of consumers but something that is a reaction to corporate actions; and that corporations in turn respond to customers’ reactions. Indeed, consumers who are sensitive to corporate social performance have values aligned with movements (e.g. green consumerism and socially responsible investing), which attempt to bring the corporation toward multi-fiduciary management (Giacalone, Paul, and Jurkiewicz, 2005).

This consumer's attempt to bring the corporation toward multi-fiduciary management is part of the influence individuals have on corporations. As Morrison and Bridwell (2011) remark, the customer is the most powerful determinant of corporate behavior, and this is why the CSR focus should be on the consumers. The authors state “Consumer Social Responsibility is the true Corporate Social Responsibility”. This is because consumers are considered the main participants in commercial activities, and if enterprises do not take consumers’ opinions into account in the research of marketing ethics, their understanding of marketing ethics will not be complete (Al-Khatib, 2005). Much more when authors like Carrigan, Szmigin, & Wright (2004) assert that the term ethical consumer carries various meanings and can be a subjective term for both companies and consumers.

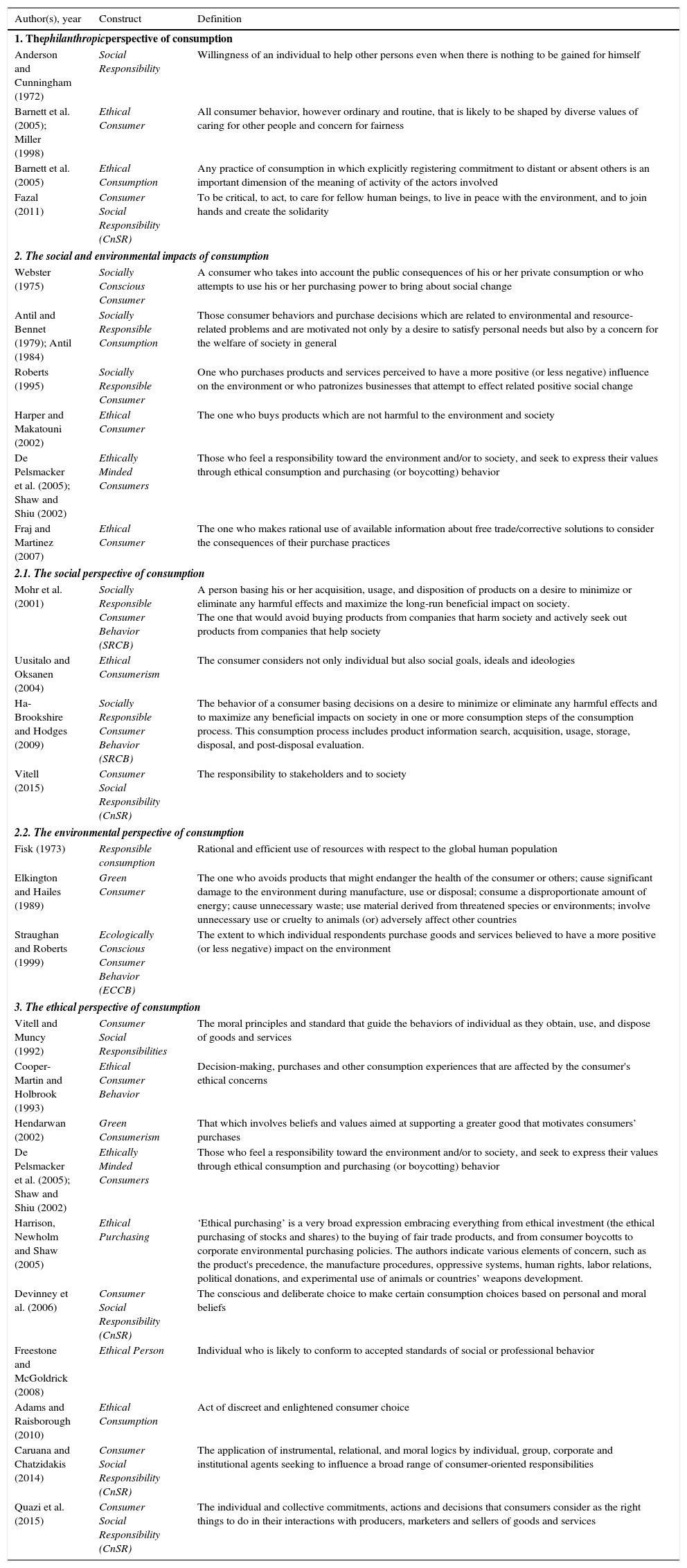

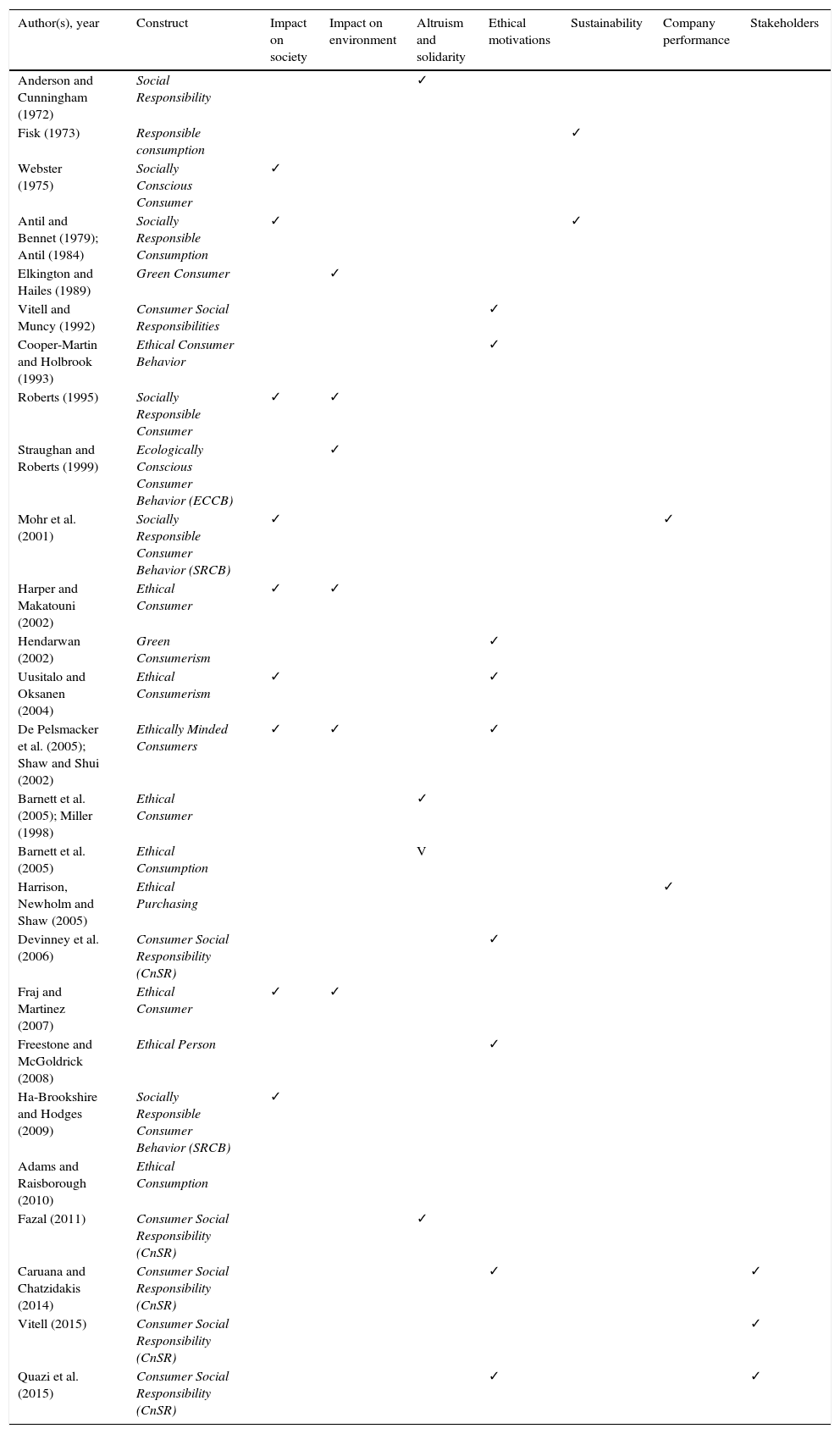

Consumer Social ResponsibilitySocial responsibility of consumers has been an important concern for researches especially since the 70s (Anderson & Cunningham, 1972; Fisk, 1973). With this long research tradition, literature has used different constructs that refer, in their terminology, to responsible, environmental or ethical attitudes and responsibilities of consumers. However, not all of the nomenclatures are in direct relation with their meanings and descriptions – that is, green consumption related to environmental issues or ethical consumption related to moral or ethical matters – what makes necessary to classify the extant literature following a content-schema.

If we focus explicitly on the nomenclature of the constructs, three groups of authors can be identified that make direct allusion to responsible, ethical and environmental consumption. First, some of the concepts specifically used terms related to responsibility of consumers, such as social responsibility (Anderson & Cunningham, 1972), responsible consumption (Fisk, 1973), socially responsible consumption behavior (Antil and Bennet, 1979, Roberts, 1995; Antil, 1984; Ha-Brookshire & Hodges, 2009; Mohr et al., 2001) or consumer social responsibility (Caruana & Chatzidakis, 2014; Devinney, Auger, Eckhardt, & Birtchnell, 2006; Fazal, 2011; Quazi, Amran, & Nejati, 2015; Vitell & Muncy, 1992; Vitell, 2015). Some others have focused on the term Ethics and refer to ethical consumption (Adams & Raisborough, 2010; Barnett, Cafaro, & Newholm, 2005; Cooper-Martin & Holbrook, 1993; Fraj & Martinez, 2007; Harper & Makatouni, 2002; Miller, 1998; Uusitalo & Oksanen, 2004) and ethical purchasing (Harrison, Newholm and Shaw, 2005), or define the ethically minded consumer (De Pelsmacker, Janssens, Sterckx, & Mielants, 2005; Shaw and Shui, 2002) and the ethical person (Freestone & McGoldrick, 2008). A third group of authors focus consumers’ environmental attitudes and behaviors of consumers and refer to green consumerism (Elkington & Hailes, 1989; Hendarwan, 2002), ecologically conscious consumer behavior (Straughan & Roberts, 1999) or, as Webster (1975), socially conscious consumer.

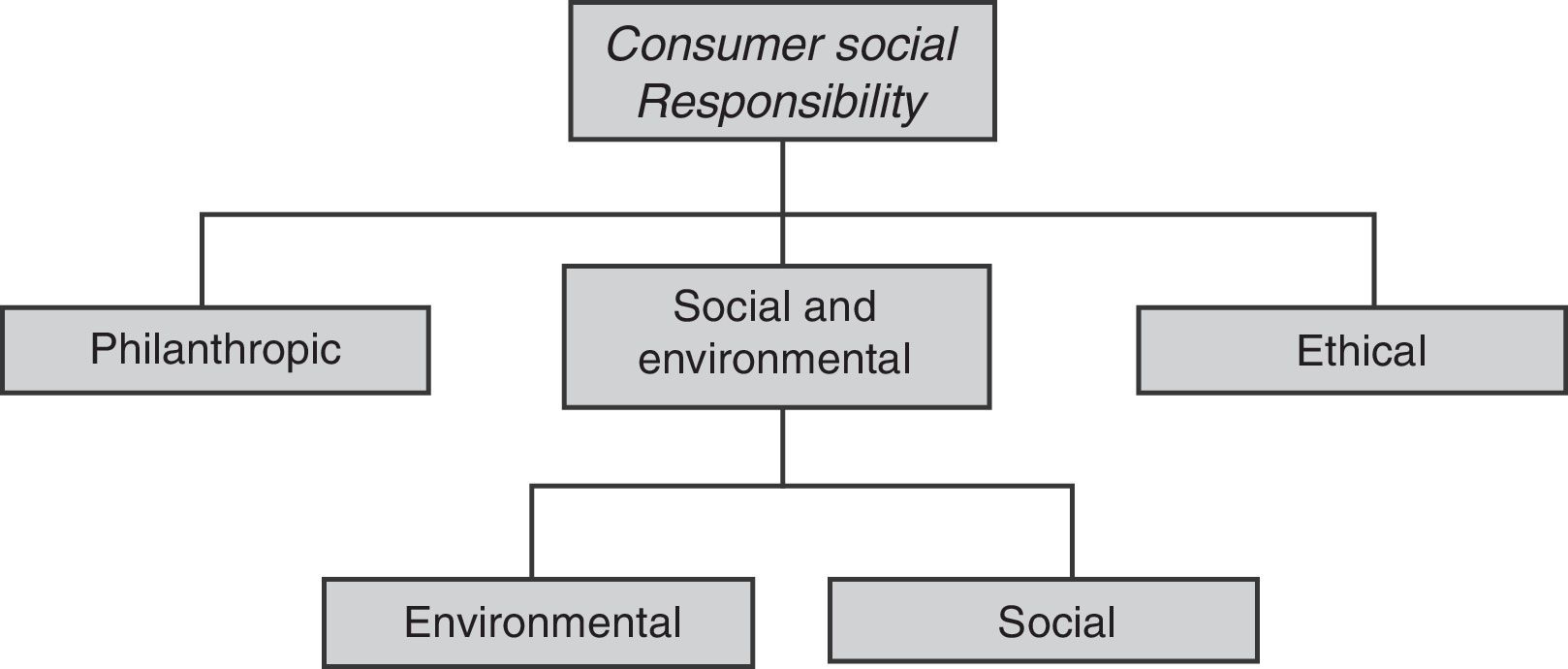

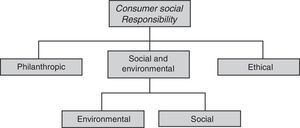

On the other hand, a deeper analysis of the constructs’ definitions and contents sheds light to the assumption of consumer responsibilities from different perspectives. In essence, an overall look at the definitions (see Table 1 for a summary of the definitions and Table 2 for a content schema) shows that almost all of the constructs refer, in their meanings, to the consumers’ impacts on the environment and/or the society, to the influence of certain moral values or ethical beliefs on the consumer's decisions, or their role on the maintenance of a sustainable system. Some of them refer specifically to values of solidarity or altruism, or imply concrete purchase decisions depending on the company performance or its responsible behaviors, and the most recent contributions make specific reference to the relations between the individual and its stakeholders. This situation leads us to classify the extant literature following a content-schema (as shown in Fig. 1) with a first section composed by those definitions related to a philanthropic perspective, a second one focused on the impacts of purchase decisions on the consumer's social and/or environmental contexts and, finally, a third group from an ethical perspective. All of them are analyzed in the next sections.

Literature review of definitions related to Personal Social Responsibility.

| Author(s), year | Construct | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Thephilanthropicperspective of consumption | ||

| Anderson and Cunningham (1972) | Social Responsibility | Willingness of an individual to help other persons even when there is nothing to be gained for himself |

| Barnett et al. (2005); Miller (1998) | Ethical Consumer | All consumer behavior, however ordinary and routine, that is likely to be shaped by diverse values of caring for other people and concern for fairness |

| Barnett et al. (2005) | Ethical Consumption | Any practice of consumption in which explicitly registering commitment to distant or absent others is an important dimension of the meaning of activity of the actors involved |

| Fazal (2011) | Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR) | To be critical, to act, to care for fellow human beings, to live in peace with the environment, and to join hands and create the solidarity |

| 2. The social and environmental impacts of consumption | ||

| Webster (1975) | Socially Conscious Consumer | A consumer who takes into account the public consequences of his or her private consumption or who attempts to use his or her purchasing power to bring about social change |

| Antil and Bennet (1979); Antil (1984) | Socially Responsible Consumption | Those consumer behaviors and purchase decisions which are related to environmental and resource-related problems and are motivated not only by a desire to satisfy personal needs but also by a concern for the welfare of society in general |

| Roberts (1995) | Socially Responsible Consumer | One who purchases products and services perceived to have a more positive (or less negative) influence on the environment or who patronizes businesses that attempt to effect related positive social change |

| Harper and Makatouni (2002) | Ethical Consumer | The one who buys products which are not harmful to the environment and society |

| De Pelsmacker et al. (2005); Shaw and Shiu (2002) | Ethically Minded Consumers | Those who feel a responsibility toward the environment and/or to society, and seek to express their values through ethical consumption and purchasing (or boycotting) behavior |

| Fraj and Martinez (2007) | Ethical Consumer | The one who makes rational use of available information about free trade/corrective solutions to consider the consequences of their purchase practices |

| 2.1. The social perspective of consumption | ||

| Mohr et al. (2001) | Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior (SRCB) | A person basing his or her acquisition, usage, and disposition of products on a desire to minimize or eliminate any harmful effects and maximize the long-run beneficial impact on society. The one that would avoid buying products from companies that harm society and actively seek out products from companies that help society |

| Uusitalo and Oksanen (2004) | Ethical Consumerism | The consumer considers not only individual but also social goals, ideals and ideologies |

| Ha-Brookshire and Hodges (2009) | Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior (SRCB) | The behavior of a consumer basing decisions on a desire to minimize or eliminate any harmful effects and to maximize any beneficial impacts on society in one or more consumption steps of the consumption process. This consumption process includes product information search, acquisition, usage, storage, disposal, and post-disposal evaluation. |

| Vitell (2015) | Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR) | The responsibility to stakeholders and to society |

| 2.2. The environmental perspective of consumption | ||

| Fisk (1973) | Responsible consumption | Rational and efficient use of resources with respect to the global human population |

| Elkington and Hailes (1989) | Green Consumer | The one who avoids products that might endanger the health of the consumer or others; cause significant damage to the environment during manufacture, use or disposal; consume a disproportionate amount of energy; cause unnecessary waste; use material derived from threatened species or environments; involve unnecessary use or cruelty to animals (or) adversely affect other countries |

| Straughan and Roberts (1999) | Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behavior (ECCB) | The extent to which individual respondents purchase goods and services believed to have a more positive (or less negative) impact on the environment |

| 3. The ethical perspective of consumption | ||

| Vitell and Muncy (1992) | Consumer Social Responsibilities | The moral principles and standard that guide the behaviors of individual as they obtain, use, and dispose of goods and services |

| Cooper-Martin and Holbrook (1993) | Ethical Consumer Behavior | Decision-making, purchases and other consumption experiences that are affected by the consumer's ethical concerns |

| Hendarwan (2002) | Green Consumerism | That which involves beliefs and values aimed at supporting a greater good that motivates consumers’ purchases |

| De Pelsmacker et al. (2005); Shaw and Shiu (2002) | Ethically Minded Consumers | Those who feel a responsibility toward the environment and/or to society, and seek to express their values through ethical consumption and purchasing (or boycotting) behavior |

| Harrison, Newholm and Shaw (2005) | Ethical Purchasing | ‘Ethical purchasing’ is a very broad expression embracing everything from ethical investment (the ethical purchasing of stocks and shares) to the buying of fair trade products, and from consumer boycotts to corporate environmental purchasing policies. The authors indicate various elements of concern, such as the product's precedence, the manufacture procedures, oppressive systems, human rights, labor relations, political donations, and experimental use of animals or countries’ weapons development. |

| Devinney et al. (2006) | Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR) | The conscious and deliberate choice to make certain consumption choices based on personal and moral beliefs |

| Freestone and McGoldrick (2008) | Ethical Person | Individual who is likely to conform to accepted standards of social or professional behavior |

| Adams and Raisborough (2010) | Ethical Consumption | Act of discreet and enlightened consumer choice |

| Caruana and Chatzidakis (2014) | Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR) | The application of instrumental, relational, and moral logics by individual, group, corporate and institutional agents seeking to influence a broad range of consumer-oriented responsibilities |

| Quazi et al. (2015) | Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR) | The individual and collective commitments, actions and decisions that consumers consider as the right things to do in their interactions with producers, marketers and sellers of goods and services |

Content-schema summary.

| Author(s), year | Construct | Impact on society | Impact on environment | Altruism and solidarity | Ethical motivations | Sustainability | Company performance | Stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson and Cunningham (1972) | Social Responsibility | ✓ | ||||||

| Fisk (1973) | Responsible consumption | ✓ | ||||||

| Webster (1975) | Socially Conscious Consumer | ✓ | ||||||

| Antil and Bennet (1979); Antil (1984) | Socially Responsible Consumption | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Elkington and Hailes (1989) | Green Consumer | ✓ | ||||||

| Vitell and Muncy (1992) | Consumer Social Responsibilities | ✓ | ||||||

| Cooper-Martin and Holbrook (1993) | Ethical Consumer Behavior | ✓ | ||||||

| Roberts (1995) | Socially Responsible Consumer | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Straughan and Roberts (1999) | Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behavior (ECCB) | ✓ | ||||||

| Mohr et al. (2001) | Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior (SRCB) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Harper and Makatouni (2002) | Ethical Consumer | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Hendarwan (2002) | Green Consumerism | ✓ | ||||||

| Uusitalo and Oksanen (2004) | Ethical Consumerism | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| De Pelsmacker et al. (2005); Shaw and Shui (2002) | Ethically Minded Consumers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Barnett et al. (2005); Miller (1998) | Ethical Consumer | ✓ | ||||||

| Barnett et al. (2005) | Ethical Consumption | V | ||||||

| Harrison, Newholm and Shaw (2005) | Ethical Purchasing | ✓ | ||||||

| Devinney et al. (2006) | Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR) | ✓ | ||||||

| Fraj and Martinez (2007) | Ethical Consumer | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Freestone and McGoldrick (2008) | Ethical Person | ✓ | ||||||

| Ha-Brookshire and Hodges (2009) | Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior (SRCB) | ✓ | ||||||

| Adams and Raisborough (2010) | Ethical Consumption | |||||||

| Fazal (2011) | Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR) | ✓ | ||||||

| Caruana and Chatzidakis (2014) | Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Vitell (2015) | Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR) | ✓ | ||||||

| Quazi et al. (2015) | Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR) | ✓ | ✓ |

Anderson and Cunningham (1972) published one of the first works that addresses social responsibility, although not directly linked to consumption patterns. They refer to social responsibility as the “willingness of an individual to help others even when there is nothing to be gained for himself”. This definition is closely related to values such as solidarity or altruism, since it considers the individual traits toward the rest of the society from a humane, philanthropic and selfless attitude. The same perspective is later used by Miller (1998) and Barnett et al. (2005) when defining ethical consumption as “all consumer behavior, however ordinary and routine, that is likely to be shaped by diverse values of caring for other people and concern for fairness”. Barnett et al. (2005) add, in this direction, that the fact of explicitly considering a commitment to distant or absent others is an important dimension of any practice of consumption. More recently, Fazal (2011) describes consumer social responsibility as a way of being critical, acting, caring for fellow human beings, living in peace with the environment, and joining hands and creating solidarity.

This first group of authors understands social and ethical consumption from a humanitarian perspective, placing the consumer as a philanthropist that seeks to help others, to care for other people or to contribute to fairness and solidarity. This positioning conceives the individual as a member of a community and enhances the positive interactions that can result from his/her relationships with others.

The social and environmental impacts of consumptionWhen considering the impacts of consumer purchase decisions, a second group of authors make a direct allusion to the individual impacts on the social and the environmental contexts. One of the first works that contributed to the consumer behavior literature from this perspective was Webster (1975), who stated that the socially conscious consumer is the one “who takes into account the public consequences of his or her private consumption or who attempts to use his or her purchasing power to bring about social change”. Webster (1975) points out the relevance of being conscious of the outcomes of our actions, and considers consumption as a useful tool that may help societies to evolve toward desirable goals. Something similar can be found in Antil's (1984) and Antil and Bennet's (1979) works on socially responsible consumption, defined as “those consumer behaviors and purchase decisions which are related to environmental and resource-related problems and are motivated not only by a desire to satisfy personal needs but also by a concern for the welfare of society in general”. This perspective is deeply related to the individual's influences on societies, and makes relevant both social and environmental impacts of consumption and purchase decisions, constituting indeed one of the most crucial perspectives within the field.

Later, Roberts (1995) defined the socially responsible consumer as the “one who purchases products and services perceived to have a more positive (or less negative) influence on the environment or who patronizes businesses that attempt to effect related positive social change”. The author uses a similar definition and, in this case, specifies the role not only of the consumer, but also of the companies that he or she supports. Fraj and Martinez (2007) also refer to the ethical consumer from the perspective of this consciousness of consequences, indicating that he or she will be “the one who makes rational use of available information about free trade/corrective solutions to consider the consequences of their purchase practices”.

Harper and Makatouni (2002) simplify this idea, stating that the ethical consumer is “the one who buys products which are not harmful to the environment and society”. More specifically, Shaw and Shui (2002) and De Pelsmacker et al. (2005) refer to the ethically minded consumers as “those who feel a responsibility toward the environment and/or to society, and seek to express their values through ethical consumption and purchasing (or boycotting) behavior”.

In summary, these definitions are based on the assumption that consumers’ decisions and actions have an impact on their social and ecological environments. Additionally to these impacts, they also support the idea that individuals will have both a power to change the world and a responsibility associated to that power. However, additional constructs and definitions can be found that focus their meanings either on the social or on the environmental consequences of consumers’ decisions, which are further explained below.

Among the authors that focus specifically on the social perspective of consumption, Mohr et al. (2001) refer to the socially responsible consumer behavior as the consumer “basing his or her acquisition, usage, and disposition of products on a desire to minimize or eliminate any harmful effects and maximize the long-run beneficial impact on society”. Three years later, Uusitalo and Oksanen (2004) stated that ethical consumerism exists when “the consumer considers not only individual but also social goals, ideals and ideologies”. Additionally, Ha-Brookshire and Hodges (2009) widen Mohr et al.’s (2001) definition, indicating that socially responsible consumer behavior is “the behavior of a consumer basing decisions on a desire to minimize or eliminate any harmful effects and to maximize any beneficial impacts on society in one or more consumption steps of the consumption process”, specifying that this consumption process “includes product information search, acquisition, usage, storage, disposal, and post-disposal evaluation”.

Recently, Vitell (2015) used one of the simplest conceptions on the field, defining consumer social responsibility as “the responsibility to stakeholders and to society”. For the first time, the term stakeholders is considered within the individual domain of action, taking into account the consumer's relationship and trait toward not only the society in general, but his/her stakeholders in particular.

These authors perceive social, responsible and ethical consumption from the perspective of the consumers’ impacts on societies, excluding the environmental sphere of action. They consider consumers’ responsibilities as the way that their impacts contribute to the evolution of the social structures where they belong, maximizing the benefits and minimizing any harm derived from their individual performance.

Secondly, among those authors that refer to environmental issues, Elkington and Hailes (1989) define the green consumer as “the one who avoids products that might endanger the health of the consumer or others; cause significant damage to the environment during manufacture, use or disposal; consume a disproportionate amount of energy; cause unnecessary waste; use material derived from threatened species or environments; involve unnecessary use or cruelty to animals (or) adversely affect other countries”. This is not a real definition, but rather enumerates explicit actions that a person can accomplish to be responsible toward the environment. From a more simplistic perspective, Straughan and Roberts (1999) refer to the ecologically conscious consumer behavior as “the extent to which individual respondents purchase goods and services believed to have a more positive (or less negative) impact on the environment”.

Not directly linked to the impacts of consumption, but specifically to green issues and sustainability matters, Fisk (1973) refers to responsible consumption, as everything related to the environment, natural resources or pollution, defined as “the rational and efficient use of resources with respect to the global human population”. This definition is in line with that of sustainable development given by the Brundtland Commission (1987), almost two decades later, where the terms environment and development were taken together for the first time. In its paper Our Common Future, sustainable development is defined as “the kind of development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. Therefore, Fisk (1973) considers responsible consumption from the perspective of one's contribution to sustainability.

This perspective is exclusively focused on the impacts of consumption on the maintenance of a sustainable system, considering the preservation of the environment as its fundamental pillar.

The ethical perspective of consumptionIn addition to all the aforementioned constructs and their associated definitions, the most common characteristic throughout the literature of responsible consumption is the focus and attention on the ethical and moral reasons to perform a particular behavior. Vitell and Muncy (1992) defined consumer social responsibilities as “the moral principles and standard that guide the behaviors of individual as they obtain, use, and dispose of goods and services”. One year later, Cooper-Martin and Holbrook (1993) established that ethical consumer behavior was based on the “decision-making, purchases and other consumption experiences that are affected by the consumer's ethical concerns”.

Hendarwan (2002) indicated that green consumerism is the one that “involves beliefs and values aimed at supporting a greater good that motivates consumers’ purchases”. The impact of social goals, ideals and ideologies, that in the end conform the ethical schema under which societies behave and operate, is also considered by Uusitalo and Oksanen (2004) in their conception of ethical consumerism, just as Freestone and McGoldrick's (2008) original argument sustains. Indeed, the latter authors define the ethical person as an “individual who is likely to conform to accepted standards of social or professional behavior”.

This same influence, but from a particular or individual point of view, constitutes the base of Devinney et al.’s (2006) definition of consumer social responsibility: “the conscious and deliberate choice to make certain consumption choices based on personal and moral beliefs”. De Pelsmacker et al. (2005) and Shaw and Shui (2002) also refer to the ethically minded consumers as those that seek to express their values through ethical consumption and purchasing (or boycotting) behavior. Additionally, Caruana and Chatzidakis (2014) make reference to the application of moral logics by individuals to influence consumer responsibilities; and Quazi et al. (2015) consider the choice of “the right things to do” toward the individual's stakeholders as a key characteristic of consumer social responsibility.

Additionally, although the authors do not directly mention ethical or moral values, Adams and Raisborough (2010) defined ethical consumption as an “act of discreet and enlightened consumer choice”. This definition implies that the consumer will be well-informed, educated and aware of the impacts of his/her purchasing choices, and therefore considers consumption as an act that will be in accordance to his/her good sense and judgment.

Lastly, Harrison et al. (2005) considered ethical purchasing as a performance that embraces “everything from ethical investment (the ethical purchasing of stocks and shares) to the buying of fair trade products, and from consumer boycotts to corporate environmental purchasing policies”. This definition is directly linked to the ethical performance of companies, specifying particular elements of concern, such as the product's precedence, the manufacture procedures, oppressive systems, human rights, labor relations, political donations, and experimental use of animals or countries’ weapons development. In this case, ethical purchasing stands as an individual reaction to organizational performance.

This third perspective is composed by authors that conceive social, responsible, ethical and even green consumption as the one that is influenced, affected or determined by the consumer's moral principles and standards, ethical concerns, beliefs and values. This assumption focuses on the congruence of the personal actions with respect to their individual and social ethical standards.

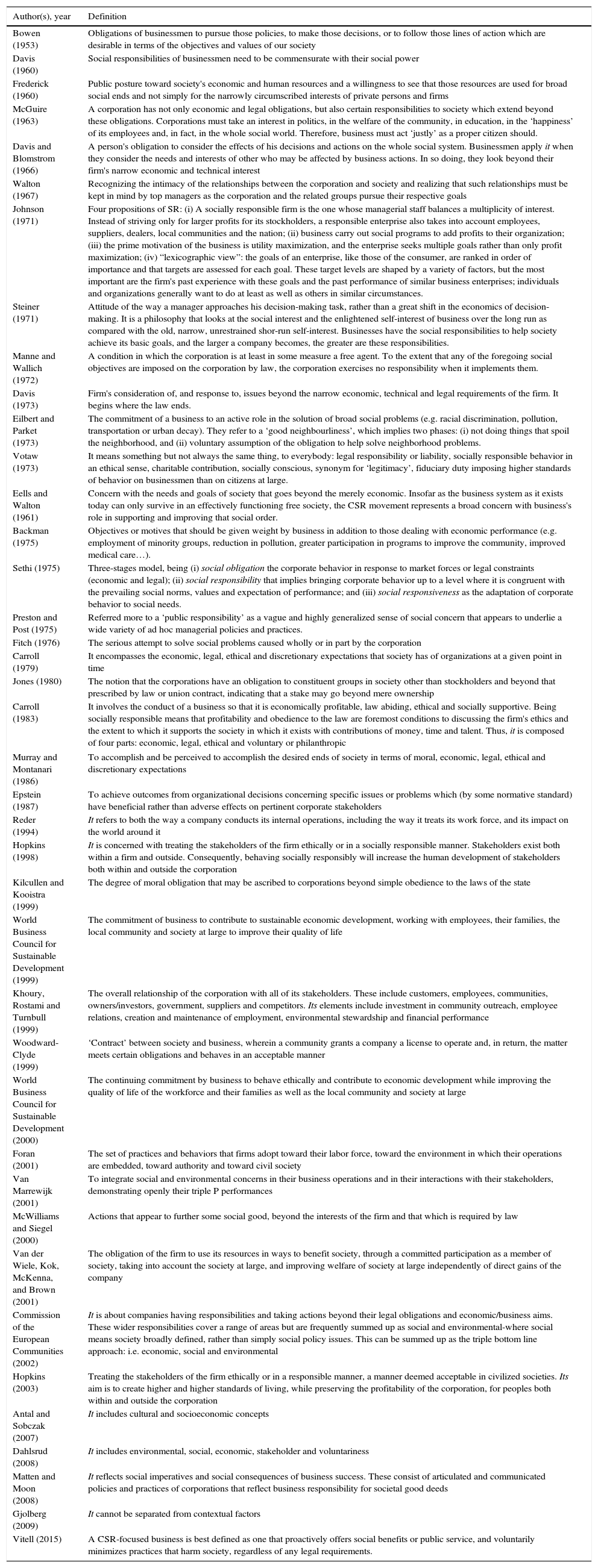

Corporate Social ResponsibilityAlthough Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) rises in the scientific literature as a discipline framed within the management field and addresses different issues related to the general spheres of the company, its enthusiasm has also been echoed in the marketing literature (Maignan & Ferrell, 2004). Concretely, during the last decades this concept has been analyzed from the perspective of consumers’ responses to CSR policies (Brown and Dacin, 1997; Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001), the outcomes derived from the application of social actions (Maignan, Ferrell, & Hult, 1999), the strategies to communicate the activities related to CSR (Drumwright, 1996; Vanhamme, 2004) and the influence and effectiveness on consumers of pro-social positioning strategies (Osterhus, 1997). Additionally, research has also analyzed other related concepts such as cause related marketing (Varadarajan and Menon, 1988) and the protection of the environment (Banerjee, Gulas, & Iyer, 1995; Manrai, Manrai, Lascu, & Ryands, 1997).

References to a concern for social responsibility appeared earlier than this (Carroll, 1999) (Table 3). They include The Functions of the Executive of Chester Barnard (1938), Social Control of Business by J. M. Clark (1939), and Measurement of the Social Performance of Business written by Theodore Kreps (1940). However, the first author that refers to the concept of CSR more specifically as we know and understand it today is Bowen (1953), who has been considered in the literature as the “Father of Corporate Social Responsibility” (Carroll, 1999) and defines it in his book Social Responsibilities of the Businessmen as those responsibilities that businessmen are reasonably expected to assume toward society. He refers to the “obligations of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action which are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of our society”.

CSR's conceptual background.

| Author(s), year | Definition |

|---|---|

| Bowen (1953) | Obligations of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action which are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of our society |

| Davis (1960) | Social responsibilities of businessmen need to be commensurate with their social power |

| Frederick (1960) | Public posture toward society's economic and human resources and a willingness to see that those resources are used for broad social ends and not simply for the narrowly circumscribed interests of private persons and firms |

| McGuire (1963) | A corporation has not only economic and legal obligations, but also certain responsibilities to society which extend beyond these obligations. Corporations must take an interest in politics, in the welfare of the community, in education, in the ‘happiness’ of its employees and, in fact, in the whole social world. Therefore, business must act ‘justly’ as a proper citizen should. |

| Davis and Blomstrom (1966) | A person's obligation to consider the effects of his decisions and actions on the whole social system. Businessmen apply it when they consider the needs and interests of other who may be affected by business actions. In so doing, they look beyond their firm's narrow economic and technical interest |

| Walton (1967) | Recognizing the intimacy of the relationships between the corporation and society and realizing that such relationships must be kept in mind by top managers as the corporation and the related groups pursue their respective goals |

| Johnson (1971) | Four propositions of SR: (i) A socially responsible firm is the one whose managerial staff balances a multiplicity of interest. Instead of striving only for larger profits for its stockholders, a responsible enterprise also takes into account employees, suppliers, dealers, local communities and the nation; (ii) business carry out social programs to add profits to their organization; (iii) the prime motivation of the business is utility maximization, and the enterprise seeks multiple goals rather than only profit maximization; (iv) “lexicographic view”: the goals of an enterprise, like those of the consumer, are ranked in order of importance and that targets are assessed for each goal. These target levels are shaped by a variety of factors, but the most important are the firm's past experience with these goals and the past performance of similar business enterprises; individuals and organizations generally want to do at least as well as others in similar circumstances. |

| Steiner (1971) | Attitude of the way a manager approaches his decision-making task, rather than a great shift in the economics of decision-making. It is a philosophy that looks at the social interest and the enlightened self-interest of business over the long run as compared with the old, narrow, unrestrained shor-run self-interest. Businesses have the social responsibilities to help society achieve its basic goals, and the larger a company becomes, the greater are these responsibilities. |

| Manne and Wallich (1972) | A condition in which the corporation is at least in some measure a free agent. To the extent that any of the foregoing social objectives are imposed on the corporation by law, the corporation exercises no responsibility when it implements them. |

| Davis (1973) | Firm's consideration of, and response to, issues beyond the narrow economic, technical and legal requirements of the firm. It begins where the law ends. |

| Eilbert and Parket (1973) | The commitment of a business to an active role in the solution of broad social problems (e.g. racial discrimination, pollution, transportation or urban decay). They refer to a ‘good neighbourliness’, which implies two phases: (i) not doing things that spoil the neighborhood, and (ii) voluntary assumption of the obligation to help solve neighborhood problems. |

| Votaw (1973) | It means something but not always the same thing, to everybody: legal responsibility or liability, socially responsible behavior in an ethical sense, charitable contribution, socially conscious, synonym for ‘legitimacy’, fiduciary duty imposing higher standards of behavior on businessmen than on citizens at large. |

| Eells and Walton (1961) | Concern with the needs and goals of society that goes beyond the merely economic. Insofar as the business system as it exists today can only survive in an effectively functioning free society, the CSR movement represents a broad concern with business's role in supporting and improving that social order. |

| Backman (1975) | Objectives or motives that should be given weight by business in addition to those dealing with economic performance (e.g. employment of minority groups, reduction in pollution, greater participation in programs to improve the community, improved medical care…). |

| Sethi (1975) | Three-stages model, being (i) social obligation the corporate behavior in response to market forces or legal constraints (economic and legal); (ii) social responsibility that implies bringing corporate behavior up to a level where it is congruent with the prevailing social norms, values and expectation of performance; and (iii) social responsiveness as the adaptation of corporate behavior to social needs. |

| Preston and Post (1975) | Referred more to a ‘public responsibility’ as a vague and highly generalized sense of social concern that appears to underlie a wide variety of ad hoc managerial policies and practices. |

| Fitch (1976) | The serious attempt to solve social problems caused wholly or in part by the corporation |

| Carroll (1979) | It encompasses the economic, legal, ethical and discretionary expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time |

| Jones (1980) | The notion that the corporations have an obligation to constituent groups in society other than stockholders and beyond that prescribed by law or union contract, indicating that a stake may go beyond mere ownership |

| Carroll (1983) | It involves the conduct of a business so that it is economically profitable, law abiding, ethical and socially supportive. Being socially responsible means that profitability and obedience to the law are foremost conditions to discussing the firm's ethics and the extent to which it supports the society in which it exists with contributions of money, time and talent. Thus, it is composed of four parts: economic, legal, ethical and voluntary or philanthropic |

| Murray and Montanari (1986) | To accomplish and be perceived to accomplish the desired ends of society in terms of moral, economic, legal, ethical and discretionary expectations |

| Epstein (1987) | To achieve outcomes from organizational decisions concerning specific issues or problems which (by some normative standard) have beneficial rather than adverse effects on pertinent corporate stakeholders |

| Reder (1994) | It refers to both the way a company conducts its internal operations, including the way it treats its work force, and its impact on the world around it |

| Hopkins (1998) | It is concerned with treating the stakeholders of the firm ethically or in a socially responsible manner. Stakeholders exist both within a firm and outside. Consequently, behaving socially responsibly will increase the human development of stakeholders both within and outside the corporation |

| Kilcullen and Kooistra (1999) | The degree of moral obligation that may be ascribed to corporations beyond simple obedience to the laws of the state |

| World Business Council for Sustainable Development (1999) | The commitment of business to contribute to sustainable economic development, working with employees, their families, the local community and society at large to improve their quality of life |

| Khoury, Rostami and Turnbull (1999) | The overall relationship of the corporation with all of its stakeholders. These include customers, employees, communities, owners/investors, government, suppliers and competitors. Its elements include investment in community outreach, employee relations, creation and maintenance of employment, environmental stewardship and financial performance |

| Woodward-Clyde (1999) | ‘Contract’ between society and business, wherein a community grants a company a license to operate and, in return, the matter meets certain obligations and behaves in an acceptable manner |

| World Business Council for Sustainable Development (2000) | The continuing commitment by business to behave ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as the local community and society at large |

| Foran (2001) | The set of practices and behaviors that firms adopt toward their labor force, toward the environment in which their operations are embedded, toward authority and toward civil society |

| Van Marrewijk (2001) | To integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interactions with their stakeholders, demonstrating openly their triple P performances |

| McWilliams and Siegel (2000) | Actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law |

| Van der Wiele, Kok, McKenna, and Brown (2001) | The obligation of the firm to use its resources in ways to benefit society, through a committed participation as a member of society, taking into account the society at large, and improving welfare of society at large independently of direct gains of the company |

| Commission of the European Communities (2002) | It is about companies having responsibilities and taking actions beyond their legal obligations and economic/business aims. These wider responsibilities cover a range of areas but are frequently summed up as social and environmental-where social means society broadly defined, rather than simply social policy issues. This can be summed up as the triple bottom line approach: i.e. economic, social and environmental |

| Hopkins (2003) | Treating the stakeholders of the firm ethically or in a responsible manner, a manner deemed acceptable in civilized societies. Its aim is to create higher and higher standards of living, while preserving the profitability of the corporation, for peoples both within and outside the corporation |

| Antal and Sobczak (2007) | It includes cultural and socioeconomic concepts |

| Dahlsrud (2008) | It includes environmental, social, economic, stakeholder and voluntariness |

| Matten and Moon (2008) | It reflects social imperatives and social consequences of business success. These consist of articulated and communicated policies and practices of corporations that reflect business responsibility for societal good deeds |

| Gjolberg (2009) | It cannot be separated from contextual factors |

| Vitell (2015) | A CSR-focused business is best defined as one that proactively offers social benefits or public service, and voluntarily minimizes practices that harm society, regardless of any legal requirements. |

Later, CSR was studied by various authors such as Davis (1960), Frederick (1960), Eells and Walton (1961), Friedman (1962) or McGuire (1963), who stated that social responsibility implies that an organization has not only economic and legal duties, but also certain responsibilities toward society that go beyond the first and traditional ones. Backman (1975) supported this statement, declaring that CSR refers to the goals and motives that go beyond the economic performance of enterprises.

It is in this decade of the 70s when the concept of CSR becomes an organization's voluntary performance (Manne & Wallich, 1972). This new perspective, which emphasizes motivations above actions, understands CSR as a system of social responsiveness (Ackerman & Bauer, 1976). Since this decade, CSR places its orientation toward the stakeholders’ satisfaction.

One of the most important attempts to classify different stages or dimensions of the social responsibility performance of businesses was made by Carroll (1979), one of the most influential authors of this research area. He proposed a conceptual model in which three different aspects or corporate social performance should be articulated and interrelated: (i) a basic definition of social responsibility, (ii) an enumeration of issues for which a social responsibility exists, and (iii) a specification of the philosophy of response (responsiveness). For Carroll, social responsibility of businesses “encompasses the economic, legal, ethical and discretionary expectations that society has of organizations at a given point of time”. These four dimensions build the map of responsibilities that a company should undertake to be considered a responsible organization, being any of its responsibilities or actions motivated by one of them.

The first dimension or component of social responsibility is the economic one, based on the natural role of businesses in society.

“Before anything else, the business institution is the basic economic unit in our society. As such it has a responsibility to produce goods and services that society wants and to sell them at a profit. All other business roles are predicated on this fundamental assumption” (Carroll, 1979:500).

This is the most important responsibility for the author, and requires the company to be efficient providing goods and services, implying the need to produce or to offer services with high quality, to develop innovations in its product and procedures, to achieve satisfactory levels of productivity within its human resources or to be able to respond adequately to its consumers’ complaints, among others.

This economic function and performance is expected to be fulfilled within the legal framework. This means that enterprises should obey the law, the “basic rules of the game” in which they are expected to operate. Then, the legal dimension represents the second part of the social responsibilities that businesses must embody.

The ethical responsibilities are composed by practices that go beyond the law, but nevertheless are expected by society. They encompass the way of behaving and the norms that societies expect companies to follow behaviors and activities that go beyond what is mandated by law, codes of conduct considered morally correct. Some examples could be the application of a code of ethical business conducts for employees, to facilitate or provide the maximum possible information about the product, the avoidance of dangerous or injurious substances, and the transparency of the management and administration of corporate finances.

Finally, the fourth group is called discretionary (or philanthropic) responsibilities. These are voluntary and not expected as the ethical ones, and “left to individual managers’ and corporations’ judgment and choice”. They are “guided by businesses’ desire to engage in social roles not mandated or required by law and not expected of businesses in an ethical sense, but which are increasingly strategic”. Driven by social norms, they are constituted by activities which aim is helping society and thus include voluntary, altruist or philanthropic activities of social action, guided by a desire of belonging to better societies. Some examples could be donations to projects of development in third-world countries, contributions to or partnerships with NGOs, the sponsorship of social, sporting or cultural events, and the support for the disadvantaged.

However, it has always been thought that the economic component refers to what the company does for itself, while the other three responsibilities define what the company does for others. Thus, the economic responsibility would not be part of the “social” components of responsibility. Nevertheless, Carroll (1999) defends the idea that what companies do in this sense is also good for society, since it consists in providing good and services, something that can be done better or worse, with greater or lesser efficiency, quality, security, etc.

Carroll's contribution has been an important basis for later researches and its definition still has validity, being the reference for many other authors in the literature (Aupperle, Carroll, & Hatfield, 1985; Carroll, 1999; Maignan et al., 1999; Wartick & Cochran, 1985). For example, regarding the social responsibilities, responsiveness and issues included in Carroll's (1979) model, Wartick and Cochran (1985) introduced them into a framework of principles, processes and policies. The authors proposed an extended model in which “social responsibilities of companies should be thought of as principles, social responsiveness should be thought of as processes and the social issues management as policies”.

In addition, Aupperle, Carroll and Hatfield (1985) operationalized the four-part definition of CSR of the same Carroll's (1979) model and separated the economic component from the legal, ethical and discretionary. They did so because the economic dimension was thought to be the main purpose of the company (“concern for economic performance”) and the other three components represented the “concern for society”.

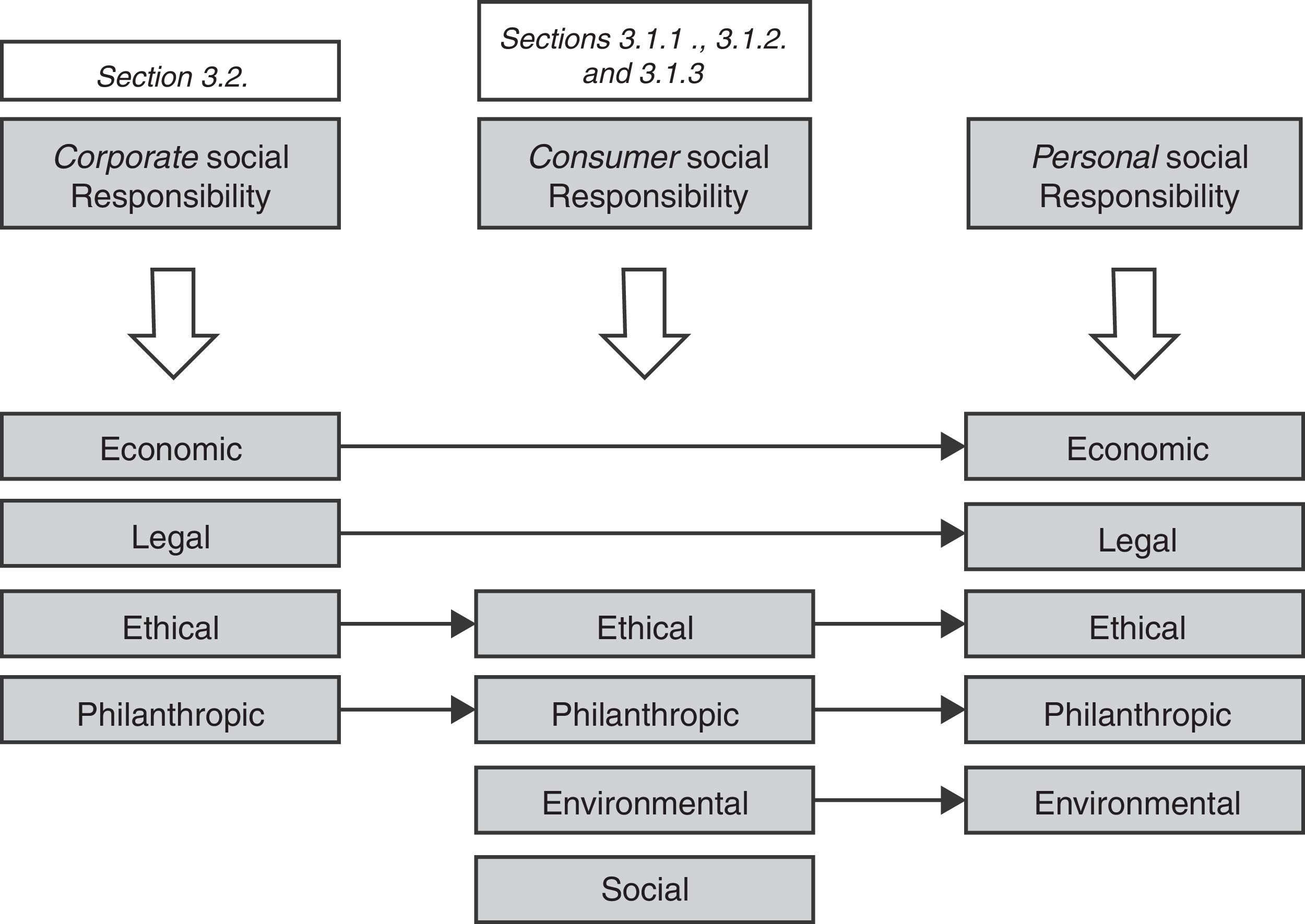

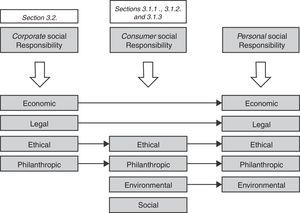

Personal Social ResponsibilityThe translation from consumer to personal social responsibilities needs to consider further spheres of individual action beyond the consumption. To correctly address the specification of the domain of PSR, we have based on the literature review of consumer social responsibilities – ethical, philanthropic, environmental and social perspectives of consumption – and corporate social responsibilities – economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic spheres of organizational action (Carroll, 1979) – in which there seems to be a gap between them that can be fulfilled by the new construct, as well as on the results of the qualitative research.

After the literature review, in-depth interviews to four researchers and a focus group interview (with 6 members) to a convenience sample of consumers were conducted, in order to help in the process of defining both the construct and its dimensions. Each of the in-depth interviews lasted between 30 and 45minutes, and the focus group one hour and a half. In all of them initial questions were related to what the participants believed to be socially responsible toward society, and which behaviors of the participants or others they believed to be considered as “personal social responsibility toward society or responsible consumption behaviors” (i.e., local purchasing, the use of public transport, environmental criteria or anti-consumption patterns, between others).

Results of the literature review indicate that some aspects of individual action are not considered in previous works on consumer responsible behavior, but nevertheless are identified as crucial by the researches and the citizens interviewed. Specifically, literature on responsible consumption behavior does not make direct allusion to the economic responsibilities of the individual – related to economic, environmental and social impacts of the way one spends his or her money – or the wide range of responsibilities given by a certain society that are delimited by law – that is, legal responsibilities – such as happens when we consider the corporate social responsibilities (see Fig. 2). Indeed, adding them as individual's responsibilities toward society appears to have a core sense, given the nature of the crisis that we have been going through for the last years.

Additionally, not all of the nomenclatures are in direct relation with their meanings and descriptions – that is, green consumption related to environmental issues or ethical consumption related to moral or ethical matters – what makes essential to align and focus a single construct that properly addresses its nomological content.

Social responsibilities of organizations have been studied during the last decades, constituting a reference for the application of the dimensions that make an organization responsible to the individual sphere. Rest (1986) presented a theory of individual ethical decision making that can easily be generalized to organizational settings. This implies the perception of organizations as individuals in the ethical sphere, and therefore allows the inclusion of organizational considerations to the personal trait. Accordingly, having delimited and accepted the concept of CSR, it would be interesting to test whether the dimensions attached to the organizational concept could be translated to individuals. Indeed, some authors have indicated that what is interesting about the rise of CSR, and the discussions around the nature of civil society, is the extent to which it skirts almost completely the role played by the everyday individual as a worker, consumer, or simply interested or uninterested bystander (Devinney et al., 2006).

Therefore, we define Personal Social Responsibility as the way a person performs in his daily life as a member of the society – and not only as a consumer – basing his decisions in a desire to minimize the negative impacts and maximize the positive impacts on the social, environmental and economic environment in the long run. This range of personal behavior, more than as a consumer role, directly and indirectly embodies the economic, legal, ethical, discretionary and environmental actions derived from the individual's role in the marketplace, the society, the environment and the world as a whole.

The economic responsibilities refer to the extent to which people purchase or consume only what they need. This means not only purchasing what they need or what they will use later (in a real and specific context an irresponsible action in this sense would be having to throw away food because it has past its use-by date), but also not spending more than what they earn. The following quote from one of the participants of the focus group is illustrative of the relevance of this dimension of PSR:

“In the last years, due to the economic crisis, we have listened several times that we, as a society, have been living beyond our means… and I personally think that this is true. We have bought things that we did not need or even things that we could not pay. Now we all have huge debts. This wouldn’t have happened if we had been economically responsible”.

This economic dimension is directly related to what previous authors have identified as reducing (Francois-Lecompte and Roberts, 2006), limiting (D’Astous and Legendre, 2009), moderating (Yan and She, 2011) and decreasing (Ocampo, Perdomo-Ortiz, & Castaño, 2014) consumption, or deconsumption behavior (Durif, Boivin, Rajaobelina, & François-Lecompte, 2011).

Second, the legal responsibilities are composed by those ground rules under which people are expected to operate. For one of the researches, “being a responsible person toward society, that is, being a responsible citizen, means to comply with the basic and common social rules”. More specifically, she added that “the legal responsibilities should focus on two core ideas: complying with the law and paying the taxes. This means not defrauding or cheating the State”.

These two responsibilities have been identified and adapted from Corporate to Personal Social Responsibility. The environmental responsibilities, which are specifically addressed in the literature of consumer behavior, are also a key factor in corporate performance – transversally considered in all its dimensions. They include those personal actions driven by a desire to have a more positive (or less negative) impact on the environment (Freestone & McGoldrick, 2008; Roberts, 1996; Straughan & Roberts, 1999). For one of the researches interviewed, PSR in general includes “the way my actions affect the environment or my local surroundings”. In the focus group, one of the participants asserted, specifically addressing these responsibilities, that:

“Having environmental responsibilities means that a person must take into account the way companies are concerned and act for the environment. For example, the way they present and sell their products. People should choose those products that use fewer plastics, carton or packages in general”.

The last two dimensions that PSR should embrace, and that are common to the literature of both corporate and consumer social responsibilities, are the ethical and the philanthropic ones.

The ethical responsibilities represent the way ethics is included in a person and his/her family's life. For one of the interviewees,

“Personal Social Responsibility requires the existence of coherence between what I expect from others, and what I actually do. To be responsible towards society a person has to be morally coherent”.

In addition, one participant argued that education is the most important ethical responsibility:

“Education is one of the most important issues that people can do to improve our society. Being responsible also means to educate and teach the incoming citizens how to live and how to do things and, of course, to act as a constant example of cohabitation, honesty and respect”.

Carroll (1979) defined these responsibilities for companies as those “societally defined expectations of business behavior that are not part of formal low but nevertheless are expected of business by society's members”. In the case of PSR, ethical responsibilities also include those additional behaviors and activities that go beyond strict legality and pertain to actions determined as “fair” and “moral” (Accar, Aupperle, & Lowy, 2001).

Finally, philanthropic responsibilities are composed by those individual actions performed to help others, that is, the extent to which people dedicate time, effort or money to helping others (i.e., collaborating with NGOs, donations or support to social activities). The inclusion of this dimension is consistent with the content and some of the conclusions of the focus group, in which all of the participants agreed to include as one of the major personal responsibilities toward society all the voluntary activities carried out to helping others. As one of the participants said:

“Being responsible towards society means that a person must do an exercise to be aware of the society's needs. It doesn’t mean that you have to solve all the problems of your community, but as part of it, it is responsible trying to help in those issues that are in your hands. This might be being a volunteer in an NGO, respecting your neighbor or sorting the trash for recycling”.

As Carroll (1979) defined this dimension for businesses, these activities comprise “purely voluntary actions, guided by a desire to engage in social roles not mandated, not required by law, and not even generally expected of citizens in an ethical sense”. The basis of this kind of responsibilities is that if an individual does not participate in them is not considered unethical per se (Carroll, 1979) but he will be considered more responsible if he is engaged in these activities.

ConclusionsThis research defines and justifies through a qualitative research the concept of Personal Social Responsibility (PSR) as the way a person performs in his daily life as a member of the society – and not only as a consumer – basing his decisions in a desire to minimize the negative impacts and maximize the positive impacts on the social, economic and environmental in the long run.

This research contributes to the consumer behavior literature proposing that citizens should be responsible not only of their purchasing choices, but also of the influence that their daily acts and decisions will have on the economic, social and environmental spheres of life. Although literature on consumer behavior has addressed ethical and responsible consumption, individuals are not only consumers and behavior has exceeded the limits of a mere economic exchange and consumption.

This article extends extant research to the domain of an updated perspective that focuses on personal behaviors that affect or are affected by further issues not considered before. While there is much literature on consumer behavior referred to constructs such as ethical, responsible, green, conscious and even social consumption, most of this research has focused on environmental or philanthropic behaviors, ignoring other issues concerning additional fields of action. This is especially important if we note that social concerns have considerably changed in recent decades, and today social problems such as the economic and the ethical crisis, unemployment or the welfare state maintenance might be taking imperative positions.

This need to update the measures and the definitions in response to a full range of social issues has been pointed out by Webb et al. (2008), going beyond those related to environmental or philanthropic behaviors, as well as the ones derived from the consumer's response to the company performance. This also occurs in other fields where certain problems, and particularly the degree of organizational interest in them, are always in a state of flux. As times change, so does the emphasis on the range of social problems that a company must meet (Carroll, 1979). Based on the literature review and the qualitative research we propose five dimensions for the PSR: economic, legal, ethical, discretionary and environmental.

This relation between CSR and individual's responsible behaviors and the influence of one on each other has been also addressed from other fields, in addition to the existing academic and research works. For example the Spanish Government, through the Ministry of Employment and Social Security, has published various reports related to Corporate Social Responsibility, some of them analyzing the needed link between organizational and individual responsible behaviors. In a synthesis document developed by the Subgroup of Socially Responsible Consumption (2011), responsible consumption is defined as “the choice of products based not only on the price-quality relation, but also on the social and environmental impacts of the products and services, as well as on the good governance of the organizations that offer them”. This statement makes direct allusion to corporate performances, since it considers its organizational policies and actions in order to accomplish an individual responsible behavior. Thus, consumption tendencies are conceived directly from the perspective of their relationship with CSR, asserting that PSR is one of the core drivers of CSR.

In addition to its contributions to marketing theory, this research holds important implications for marketing managers. For companies where strategies and goals are based on responsibility, transparency and mutual respect, Personal Social Responsibility stands as a fundamental and undeniable pillar which affects not only to its role on the development of a new system, but also helps to improve and amplify the effects that CSR can have on society as a whole. In essence, a deeper understanding of the evolution of both organizational and individual responsible and ethical behaviors, will make possible to enhance the promotion of CSR derived from the advancement of responsible citizens. In essence, it would be a matter of converge in both theory and practice the personal and corporate performances, considering that a person who lives as a family member in a certain society, making daily decisions about the education of his/her children, the interaction with the neighbor, or where and how to do the shopping, will be the same person that is an employee or a manager in a company and, in the same way, decides how to perform and which will be the best strategy not only for the firm, but also for the rest of the society. All these reasons make necessary to continue, on the basis of past research, to define and update responsible consumption and individual behaviors, tendencies and measures.

Based on this core idea, further works will be needed to measure the PSR and the specific five dimensions, as well as to understand responsible behaviors, characteristics and, finally, the impact that behaving ethically will have on one's personal life. In addition, future research can examine new measurement models of personal responsible behaviors, as well as when they occur and how they relate to corporate performance. This will improve the existing line of investigation that analyzes and links CSR to consumer behavior. Moreover, it is important to investigate the extent to which this PSR concept and its dimensions can be developed as a measurement model and adapted to empirical research and its replication on different societies and cultures (Hofstede, 1991) to make PSR a generally applicable construct.

Conflict of interestNone declared.