We investigate and compare how salespersons within an independent-based culture (the Netherlands) and an interdependent-based culture (the Philippines) experience and self-regulate pride that is evoked through praise and recognition by their managers. This self-regulation differentially influences behavior toward customers (through adaptive resource utilization and effort put forth) and colleagues (via company citizenship behaviors). For Dutch employees, the impact of pride on adaptive resource utilization and working hard in front of customers was moderated by dispositional proneness to pride and the tendency to self-regulate one's pride so as to avoid hubris; toward colleagues, the experience of pride directly affected citizenship behaviors as main effects. For Filipinos, experienced pride had main effects on adaptive resource utilization and working hard in front of customers. With respect to citizenship behaviors, the effects of experienced pride were moderated by dispositional proneness to pride. As firms operate in international contexts and seek to sell to people from different cultures, managers need to understand how pride and its self-regulation function so as to better select, train, coach, compensate, and manage the salesforce.

Investigamos y comparamos el modo de experimentar y autorregular el orgullo de los vendedores dentro de una cultura basada en la independencia (la holandesa) y una cultura basada en la interdependencia (la filipina), evocado a través del elogio y del reconocimiento por parte de sus gestores. Dicha autorregulación influye de diversos modos en el comportamiento hacia los clientes (a través de la utilización de los recursos adaptativos y del esfuerzo propuesto) y los compañeros (a través de los comportamientos cívicos de la empresa). Para los empleados holandeses, el impacto del orgullo sobre la utilización adaptativa de los recursos y el trabajo duro frente a los clientes fue moderado por la tendencia a la disposición al orgullo y la inclinación a autorregular el orgullo propio a fin de evitar la arrogancia hacia los compañeros. La experiencia del orgullo se ve directamente afectada por los comportamientos cívicos como elementos principales. Para los filipinos, el orgullo experimentado tuvo efectos mayores sobre la utilización de los recursos adaptativos y el trabajo duro frente a los clientes. Con respecto a los comportamientos cívicos, los efectos del orgullo experimentado fueron moderados por la propensión a la disposición al orgullo. Como las empresas operan en contextos internacionales y tratan de vender productos a las personas de diferentes culturas, los gestores deben comprender el modo de funcionamiento del orgullo y de su autorregulación, de cara a seleccionar, formar, entrenar, compensar y gestionar de un modo mejor a su fuerza de ventas.

One of the key drivers of performance of salespeople was long ago speculated to be ego-drive (Mayer & Greenberg, 1964). Ego-drive has not been studied systematically in marketing and has been defined in various ways, referring to motivation, a “need to conquer”, and pride. We attempt in this article to provide an in-depth study of the role of pride in selling, as grounded in basic research in psychology and using a quasi-experimental field methodology in a cross-cultural setting.

Pride is defined as the phenomenological experience of “joy over an action, thought, or feeling well done” (Lewis, 2000, p. 630), and is frequently contrasted with shame (Mascolo & Fischer, 1995). Lazarus (1991, p. 271) specifies the “core relational theme” for pride as “enhancement of one's ego-identity by taking credit for a valued object or achievement, either our own or that of someone or group with whom we identify”. A core relational theme is the “central…relational harm or benefit in adaptational encounters” that underlies an emotion (Lazarus, 1991, p. 121).

Pride: causes and effectsPride has personal and social functions, and its focus of attention is on both the self as agent and the self as object (Barrett, 1995). Personally, pride helps to maintain self-esteem, signal to oneself important standards, and facilitate the acquisition of information about the self as object and agent (Barrett, 1995). Socially, pride shows others that one has achieved valued outcomes, and it promotes a striving for dominance or superiority over others (Barrett, 1995; Cheng, Tracy, & Henrich 2010; Erevelles & Fukawa, 2013; Mascolo, Fischer, & Li, 2003).

Pride is one of the few, and perhaps the only, positive self-conscious emotion, in contrast to many common negative self-conscious emotions (e.g., shame, guilt, embarrassment, envy, jealousy). Very little research exists even in psychology investigating pride, and indeed Tangney (2003, p. 395) observes, “Of the self-conscious emotions, pride is the neglected sibling, having received the least attention by far.” But as with other emotions, pride arises in response to primary appraisals of the personal implications of an event that has happened or is anticipated to happen to oneself (Scherer, Schorr, & Johnstone, 2001; Smith & Kirby, 2001). Once activated and experienced, pride provides motivational force, barring contingencies discussed below, to promote behavior that confirms, perpetuates, and even enhances one's self-worth, particularly in social settings. It works as a reinforcement, thus stimulating on-going action (Carver & Scheier, 1990), and ‘loosens’ a person's information processing, resulting in more creativity and flexibility (e.g., Fredrickson, 2001; Schwarz & Bless, 1991).

In our study, we examine the effects of pride stemming from praise and recognition that a manager gives to his/her subordinate, which is further observed by either colleagues or customers of the employee. The praise and recognition are manipulated by use of a scenario given to salespersons (see “Method” section). Thus, given an appraisal of an episode where one is praised and given recognition, and as a result experiences pride, the experienced pride, ceteris paribus, will lead to greater use of adaptive communication resources (e.g., the ability to change one's interpersonal approach when needed; the range of communication techniques that one is skilled in using) and greater effort (henceforth called “working hard”), which are two key motivational processes studied in the marketing salesforce literature (e.g., Spiro & Weitz, 1990; Sujan, Weitz, & Kumar, 1994). As one experiences pride and feels the effects of this positive personal emotion, employee salesperson may also wish to expansively embrace coworkers and reach out with a helping hand. Indeed, research in the past has confirmed that individuals with positive feelings engage in altruistic and pro-social behaviors (e.g., Clark & Isen, 1982; Isen & Simmonds, 1978).

Pride is also a function of secondary appraisals: that is, it is subject to “whether any given action might prevent harm, ameliorate it, or produce additional harm or benefit” (Lazarus, 1991, p. 133). Lazarus (1991, p. 134) captures the essence of secondary appraisals by use of the following metaphor, where a person figuratively asks him/herself when experiencing pride, “What, if anything, can I do in this encounter, and how will what I do and what is going to happen affect my well-being?” More specifically, when one experiences pride, he/she evaluates and chooses a coping option. Lazarus (2001, pp. 43–44) suggests that the following concrete issues might be addressed, again speaking figuratively: “Do I need to act? What can be done? What option is best? Am I capable of carrying it out? What are the costs and benefits of each option? “In this regard, we will investigate two self-regulatory mechanisms that might moderate the effects of pride on performance of salespersons: on the one hand, explicit strategic actions of the salesperson, which aim at regulating one's pride so as to avoid it getting out of hand and corrupting one's task motivation (hence, called “motivation management”); on the other hand, a dispositional factor that regulates the expression of pride (termed “proneness to pride”).

Motivation managementA key secondary appraisal for pride in the selling situation is the self-regulation or management of hubris. Hubris refers to “exaggerated pride or self-confidence” that can result in retribution and is sometimes called, pridefulness (Lewis, 2000, p. 629). In contrast to pride, where the focus is on one's actions (e.g., “My hard work and persistence led to my success”), under hubris, one's successes are attributed to the global self (e.g., “I am the best salesperson in this company and no one sells like I do”). Hubris is associated with being “puffed up” and can result in displays of grandiosity and narcissism (Morrison, 1989). Hubris obviously has negative social consequences, as it might break down communication and even interfere with the wishes and needs of others and hence lead to interpersonal conflict (Lewis, 2000, p. 630).

Hubris is clearly something to be avoided in many organizational situations, where salespeople attempt to convince customers to buy products or services from them. Success depends on the salesperson's ability to avoid or at least manage one's pride, so that it does not turn into hubris. Gross (2002) terms the general process here, response-focused self-regulation, because a person must control emotion response tendencies, lest they get out of hand (see also, Gross, John, & Richards, 2000). To refer to the specific response-focused emotion regulation applied to pride in the selling context, we use the term, motivation management, as the person strives to self-regulate pride in order to keep up his/her motivational impetus. To the best of our knowledge, such a self-regulatory mechanism has not been studied before. Motivation management is especially a concern when dealing with customers because salesperson–customer relationships are directly tied to performance of both the salesperson and the company with which one works.

Motivation management should be relatively less of an issue when relating to coworkers as opposed to customers. In our study, in addition to studying the relationship of salespersons to their customers, we examine the relationship of salespersons with coworkers, primarily through the performance of company citizenship behaviors. Company citizenship behaviors refer to actions that, while not part of one's job description, benefit the firm or coworkers (e.g., attending meetings not required; helping others; Organ & Paine, 1999). Interpersonal relationships between salespersons and co-workers under extra-role conditions are not as sensitive and as directly tied to the livelihood of the firm and employees as are employee–customer relationships, and moreover, the day to day nature of coworker contacts in selling contexts and the specific altruistic-like character of company citizenship behaviors are such as to be less likely to elicit hubris. Experiences of pride with coworkers therefore do not have to be self-regulated by motivation management to the extent that they do with customers.

Dispositional proneness to prideA second moderator of the relationship between experienced pride and performance that we wish to investigate is proneness to feeling pride as an individual difference. Gross et al. (2000, p. 713) introduced the general concept of “dispositional expressivity” in this regard, which they define as “stable individual differences in emotion-expressive behavior”. Gross et al., (2000, p. 715) hypothesized that dispositional expressivity will have either main or interaction effects, depending on “display rules – cultural, gender, and personal norms that should express particular emotions.” However, Gross et al. (2000) did not specify or test particular display rules in their study, which is a goal in our research (see section “Self-regulation of pride in cultural context”).

Gross et al. (2000) called their main effect hypothesis, the fixed modulation model. Here emotional expressivity was said to have main effects in their study such that “an increment in emotion experience is translated into a constant increment in expressive behavior. Thus dispositionally low- and high-expressivity individuals would differ in the amount of expressive behavior at any given level of emotional experience, but this difference is constant” (Gross et al., 2000, p. 714). Gross et al. (2000) termed their interaction hypothesis, the dynamic modulation model. Here people low in the disposition dissociate emotion expression from emotion experience: “To keep emotion-expressive behavior constant across the whole range of [subjective emotion], low-expressivity individuals would have to engage in some modulation at low levels of emotion experience but increasingly greater modulation at higher levels of emotion experience. As a result of this dynamic modulation process, low-expressivity individuals would exhibit more or less the same limited amount of expressive behavior regardless of the intensity of their emotional experience” (Gross et al., 2000, pp. 714–715). But people high in the disposition are thought to regulate the effects of their emotion experience to a greater extent such that, as emotion experience increases, greater observable expressive behavior occurs. Unlike Gross et al. (2000) who studied expressive behavior as a dependent variable and who used a general emotion expressivity scale and studied students, we desire to study the effects of the specific disposition of proneness to pride on the relationship between experienced pride and performance of salespeople. Because “little empirical research has been conducted to examine individual differences in proneness to pride in self” (Tangney, 2003, p. 395), we developed specific measures for dispositional proneness to pride in our particular organizational context (see “Method” section).

Self-regulation of pride in cultural contextWe turn now to the effect of culture on organizational citizenship behaviors, as well as on adaptive resource utilization and working hard, when pride is experienced by salespersons. Because different emotion display rules exist between the Netherlands and the Philippines our research context, we expect a dynamic modulation of the effects of experienced pride by motivation management and dispositional proneness to pride in these two cultural contexts, but only under the conditions developed below. These conditions represent different impression-management motives (see Bolino, 1999).

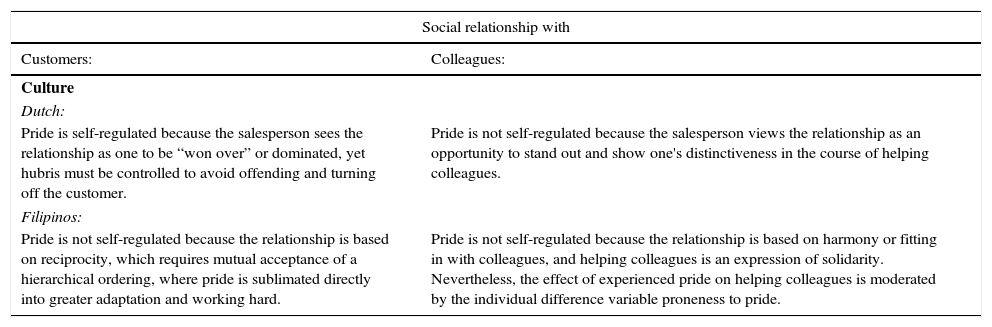

In our field study, we manipulate the experience of pride by salespersons, and felt pride then becomes an emotional state potentially subject to self-regulation in interactions with customers and in interactions with coworkers. The self-regulation of pride in these two situations will be shown below to be governed by specific cultural factors, such that the different cultural imperatives found in the Netherlands and the Philippines interact with particular demands and implications present in salesperson–customer and in salesperson–coworker relationships to yield four distinct hypotheses. Table 1 foreshadows these hypotheses. Note that our study can be considered a quasi-experiment wherein hypotheses and relationships in our models are formally compared across groups (i.e., between Dutch and Filipino salesforces).

Culture and the social situation interact to determine how experienced pride is self-regulated versus allowed to function as an uninhibited main effect.

| Social relationship with | |

|---|---|

| Customers: | Colleagues: |

| Culture | |

| Dutch: | |

| Pride is self-regulated because the salesperson sees the relationship as one to be “won over” or dominated, yet hubris must be controlled to avoid offending and turning off the customer. | Pride is not self-regulated because the salesperson views the relationship as an opportunity to stand out and show one's distinctiveness in the course of helping colleagues. |

| Filipinos: | |

| Pride is not self-regulated because the relationship is based on reciprocity, which requires mutual acceptance of a hierarchical ordering, where pride is sublimated directly into greater adaptation and working hard. | Pride is not self-regulated because the relationship is based on harmony or fitting in with colleagues, and helping colleagues is an expression of solidarity. Nevertheless, the effect of experienced pride on helping colleagues is moderated by the individual difference variable proneness to pride. |

We can characterize a key difference between the Dutch and Filipinos in terms of how the self is construed in both cultures. Likewise, another key difference between the Dutch and Filipinos lies in how they relate to other persons under horizontal social relationships (e.g., with colleagues) versus hierarchical social relationships (e.g., with customers). The combination of self-construal and nature of relationship with others in cultural context determines how pride is differentially self-regulated and, in turn, what effects occur on adaptive selling, working hard, and company citizenship behaviors.

Consider first self-construal. Researchers have found that two construals of the self can be identified in people, depending on the culture within which one has been raised and lives (e.g., Hess & Kirouac, 2000; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Shweder & Bourne, 1984; Triandis, 1995).

The Dutch, like many people in Western cultures, tend to experience an independent self-concept, which is characterized by an emphasis on personal goals, personal achievement, and appreciation of one's differences from others. People with an independent self-concept tend to be individualistic, egocentric, autonomous, self-reliant, and self-contained. They place considerable importance on asserting the self and are driven by self-serving motives. The individual is the primary unit of consciousness, with the self coterminous with one's own body. Relationships with others frequently serve as standards of self-appraisal, and the independent self takes a strategic posture vis-à-vis others in an effort to express or assert one's internal attributes. Emphasis is placed on displaying one's attributes or feelings (e.g., revealing anger, showing pride). The normative imperative is to become independent from others and discover one's uniqueness.

Filipinos, like many people in Eastern cultures, tend to experience an interdependent self-concept, which is characterized by stress placed on goals of a group to which one belongs, attention to fitting in with others, and appreciation of commonalities with others. People with an interdependent self-concept tend to be obedient, sociocentric, holistic, connected, and relation oriented. They place much importance on social harmony and are driven by other-serving motives. The social relationships one has are the primary unit of consciousness, with the self coterminous with either a group or set of roles one has with individuals across groups. Relationships with others are ends in and of themselves, and the interdependent self takes a stance vis-à-vis others of giving and receiving social support. One's personal attributes are secondary and are allowed to change as needed in response to situational demands. Emphasis is placed on controlling one's attributes or feelings (e.g., curbing displays of anger so as to avoid conflict). The normative imperative is to maintain one's interdependence with others and contribute to the welfare of the group.

It is important to consider the self-construal of salespersons because the self-concept both mediates and regulates behavior. That is, the self-concept “interprets and organizes self-relevant actions and experiences; it has motivational consequences, providing the incentives, standards, plans, rules, and scripts for behavior; and it adjusts in response to challenges from the social environment” (Markus & Wurf, 1987, pp. 329–330). Very little empirical research exists on independent and interdependent selves, per se, in the Philippines and the Netherlands, but we can draw upon the related notions of individualism and collectivism (e.g., Triandis, 1995; Triandis, Bontempo, Villareal, Asai, & Lucca 1988). In this regard, Hofstede's (2001) research with the Individualism Index (II) which was based on investigations on IBM employees, is revealing. The II is normed from 0 to 100 and was originally applied to employees in 50 countries around the world. Employees in the Netherlands had a score of 80 on this scale; employees in the Philippines had a score of 32 (http://geert-hofstede.com/countries.html). This suggests that the Dutch should be relatively individualistic and exhibit an independent-based self, whereas Filipinos should be relatively collectivistic and display an interdependent-based self.

We expect that Dutch employees, consistent with an independent self-construal, will strive to be unique, to promote personal goals, to feel self-assured, and to compare themselves with others so as to stand out. To the extent that one feels proud of his/her accomplishments, it is anticipated that pride will function to express one's individuality and to differentiate oneself from others. In a parallel manner, we expect that Filipino salespersons, consistent with an interdependent self-construal, will be concerned especially with on-going relationships and will endeavor to maintain interdependence, to perform their part of group actions on the job, to adjust to and fit into their groups and relationships, and in general to promote group welfare. When feelings of pride emerge, it is anticipated that they will function to promote group harmony. However, as developed below, how this happens, as either a main effect or under moderation by other factors, will be guided by the particular social situation within which one finds oneself.

What is the role of different social settings (particularly as manifest in interpersonal relationships) in the self-regulation of pride for Dutch and Filipino employees? Relationships with customers are hierarchical with the salesperson dependent upon the customer for consummating a sale. Relationships with colleagues are relatively horizontal with both parties more or less on equal footing. For the Dutch, interactions with others are governed primarily by the core self and how it interfaces with the particular social setting at hand. The core self is the set of personal attributes, attitudes, intentions, values, and goals that a person views as defining oneself and guiding his/her actions.

Independent culture/horizontal relationshipsWhen a Westerner, such as a Dutch salesperson, feels pride, this tends to be associated with personal agency and high self-esteem (Kitayama, Markus, Matsumoto, & Norasakkunkit, 1997). In interactions with colleagues, pride is allowed free reign (in the sense of functioning as a main effect) and by doing good (i.e., expressing one's pride by engaging in company citizenship behaviors; see “Method” section for dimensions and measures of these), one both stands out and expresses the self as a worthy person (cf. Clark, 2004). Indeed, when interacting with colleagues, such expressions of pride help the Dutch salesperson create a greater contrast with colleagues and contribute to verification that the core self is virtuous and worthy. Prior research has shown that salespersons in independent cultures do not down-regulate their pride in front of their colleagues (Verbeke, Belschak, & Bagozzi, 2004). Here, then, pride functions as a main effect on the conduct of company citizenship behaviors because it reinforces and promotes a positive core self. In this respect, we hypothesize the following direct effects of pride for Dutch salespersons:Hypothesis 1 When Dutch salespersons interact with colleagues, greater felt pride will lead directly to increased execution of company citizenship behaviors.

With customers, by contrast, pride in Dutch salespersons must be self-managed so as to avoid hubris and its damaging consequences to the relationship and the chance for a sale. On the one hand, pride presses one forward to “convince the customer”, “close the deal”, and “win the sale”, all of which reflect pride's tendency for Westerners to show dominance/superiority (Barrett, 1995, Table 2.1) and to use the situation to affirm one's high self-esteem. On the other hand, the salesperson knows that coming on too strongly, showing off, or bragging can damage the relationship with the customer. Hence, the need by Dutch salespeople to self-regulate pride by motivation management (Verbeke et al., 2004). Yet, down-regulating their pride to avoid hubris with customers is not only at odds with the cultural values of Dutch salespersons to maintain an independent self-construal (Kitayama et al., 1997), but it also has to act against their dispositions in the form of individual proneness to pride. Therefore dispositional proneness to pride of salespersons should moderate the down-regulation process (i.e., the interaction between pride and avoiding hubris), resulting in a three-way interaction overall: when proneness to pride is high, motivation management to avoid hubris also must be high to transform pride into adaptive selling and working hard. We thus expect to find the following three-way interaction:Hypothesis 2 When Dutch salespersons interact with customers, greater felt pride will lead to greater use of adaptive resources and working hard, the greater the motivation management (i.e., the more that hubris is avoided) and the greater the proneness to pride.

For Filipinos, interactions with others are governed primarily by the presented or public self and how this interfaces with the specific social situation at hand, compared to Dutch salespersons who focus on the core or personal self which is the most important facet of the self-concept for independent-based cultures where persons attempt to stand-out as individuals. The presented self refers to the image that a person displays publicly to others, especially to comembers of one's salient groups (Crozier & Metts, 1994). One's presented self is thought to arise through a process of self-definition as a function of one's group membership, where the imperative is to promote harmonious relationships within the group (Markus & Kitayama, 1991).

An important concept governing social behavior for Filipinos is that of face, which is defined as “the respectability and/or deference which a person can claim for himself from others, by virtue of the relative position he occupies in his social network, and the degree to which he is judged to have functioned adequately in that position as well as acceptability in his general conduct” (Ho, 1976, p. 883; see also Kim & Nam, 1998; Reeder, 1987). With respect to relationships with colleagues, the moral imperative is to both gain face and avoid loss of face. This is done by fulfilling the duties and obligations of one's social role (because this helps one meet expectations consistent with his/her status, and neglecting to do so results in personal loss of face) and helping colleagues meet their duties and obligations (thereby lessening the chance that the failure of colleagues to meet the expectations of their social roles will become a collective, shared shame resulting in everyone's loss of face). But unlike Western cultures where personal agency is tied closely to personal achievement, self pride, and the core self (e.g., Lewis, 2000), and pride and high self-esteem are closely coupled (Kitayama et al., 1997), face in Eastern cultures with nonhierarchical relationships (which the relationship of salespersons to colleagues is) occurs within a climate of ambiguity in agency (Matsumoto, Kudoh, Scherer, & Wallbott, 1988), where individual achievements and personal pride are secondary to shared accomplishments and collective pride. Indeed, when one meets social expectations and attains success, honor is brought to the group. One comes to attribute his/her own accomplishments not so much to the self but as consequences of the group and relationships one has with co-members. Thus, success, when it occurs, is not to be expressed in personal pride, per se, but rather in praise of colleagues; and one self-regulates one's own pride so as to promote harmony and fit-in better. Company citizenship behaviors, then, become vehicles for managing one's pride in socially acceptable ways, removing the necessity for motivation management actions. But this should happen, the more that one is prone to feel pride. Cultural norms press Filipinos not to express pride publicly for personal accomplishments (because this tends to make the person standout and to make it harder to fit-in). The effect is to disconnect the experience of personal pride from motivation to a certain extent. However, a disposition to feel pride should counteract such tendencies. Thus, Filipinos with high (versus low) proneness to pride should be better able to feel pride and express it by transforming it into company citizenship behaviors (i.e., pride stimulated by the supervisor bears fruit for the group, the more the person is prone to feel pride). For the interdependent culture dominating within the Philippines, we thus expect to find the following two-way interaction:Hypothesis 3 When Filipino salespersons interact with colleagues, greater felt pride will lead to increased execution of company citizenship behaviors, the greater the proneness to pride.

With respect to the relationships of Filipino salespersons with customers, the nature of face is quite different than with colleagues. Such hierarchical relationships are governed by the norm of reciprocity (Mao, 1994) rather than the need to fit in. That is, the salesperson curries favor and a sale from the customer in return for respect and deference, over and above the commercial aspects of the exchange manifest in qualities of the product or service. Stability in the relationship, which both parties often wish to sustain over a long period of time because of switching costs, will result in harmonious interdependence to the extent that the customer and salesperson accept the disparity in status in their roles and act accordingly in coordinated, mutual ways. This is in contrast to the relationship between customers and salespersons in the Dutch culture, where, despite the status disparity, the employee strives to win the sale by aggressively convincing the customer and getting him/her to yield to the acumen and skill of the salesperson so to speak. In short, pride for Filipinos when relating to customers is not self-regulated (and thus not moderated by motivation management) but rather is directly transformed into better adaptive resource utilization and working hard to fulfill the reciprocity called for by the role and needed to build a balanced hierarchical relationship. Furthermore and similar to feeling pride in horizontal relationships, cultural norms press Filipinos not to feel and express personal pride. We therefore do not expect proneness to pride to moderate the effect of felt pride on adaptive resource utilization and on working hard. For the interdependent culture dominating within the Philippines, we thus hypothesize the following:Hypothesis 4a When Filipino salespersons interact with customers, greater felt pride will lead to greater use of adaptive resources and working hard. Proneness to pride and motivation management are expected to have main effects on adaptive resources utilization and working hard for Filipinos interacting with customers.

Questionnaires were distributed randomly to 5 salespersons in each of 61 Dutch firms selling industrial products and services. Each participant received a gift worth 10 Euros. A total of 93 completed questionnaires were received, for a response rate of 30.5%. The sample consisted of 73% men, 27% women. The distribution of respondent ages was 19% less than 30 years old, 53% from 31 to 40 years old, 16% from 41 to 50 years old, and 12% 51 years old or older. A total of 15% of respondents had worked less than 2 years, 50% had worked from 2 to 6 years, and 35% had worked 7 years or more with their company. In terms of education, 18% had a university degree, while the rest were graduates of high schools or vocational schools. This represents a slightly higher percentage of college graduates than is typical in Europe for business-to-business salespersons.

Similarly, questionnaires were distributed randomly to up to 8 salespersons in each of 16 Philippine companies selling similar industrial products and services as the Dutch sample. Each participant received a gift worth about 10 Euros. A total of 119 completed questionnaires were obtained, for a response rate of 93%. The sample consisted of 62% men and 38% women. The distribution of respondent ages was 46% less than 30 years old, 47% from 31 to 40 years old, and 7% 41 years old or older. A total of 24% of respondents had worked less than 2 years, 47% had worked from 2 to 6 years, and 29% had worked 7 years or more with their company. In terms of education, 56% had a university degree, while the rest had completed vocational studies. This breakdown in education is typical in the Philippines for business-to-business salespeople.

Measures (see Appendix)Experienced pride. Research by Shaver, Schwartz, Kirson, and O’Connor (1987) shows that pride falls under, or shares a common core of relational themes with, the family of happiness emotions. Likewise, Lazarus (1991, p. 271) points out that pride and happiness share “a common juxtaposition…as in the statement ‘He (she) is my pride and joy”’. To measure experienced pride, we asked the salespersons to read, and place themselves in place of a protagonist in a scenario where the salesperson receives laudatory feedback from his/her sales manager, and the performance of the salesperson additionally receives recognition by colleagues and is mentioned in a newsletter that salespeople and customers receive (see Appendix). The salespersons were then asked to indicate how they would personally feel in the situation in question. The scenario and the items for measuring pride were taken from Verbeke et al. (2004). Three items measured cognitive self-appraisals of pride, three additional items measured happiness-related reactions to the experience of the events in the scenario (e.g., as a result of experiencing the events in the scenario, “I think that I am a happy employee”). Responses to the above items and all remaining items (unless otherwise indicated below) were recorded on 7-point, “completely disagree”-“completely agree” scales. Our approach followed contemporary practices in psychology, whereby emotions are indirectly induced by asking respondents to put themselves in the place of a protagonist in a vignette, wherein pride is manipulated (e.g., Roseman, 1991). Recent research shows that direct manipulation and scenario methods produce converging results for the measurement of emotions (e.g., Robinson & Clore, 2001). The Filipino and Dutch salespersons then become controls for each other in our quasi-experiment.

Motivation management. Motivation management is a type of emotion regulation that Gross (2002, p. 282) terms, response-focused strategies: “things we do once an emotion is already underway, after the response tendencies have been generated.” To measure the employee's self-management of motivation to control their pride, in the sense of avoiding hubris, we used three items (e.g., when feeling proud, “I try not to get too self-assured so that I am able to keep striving for higher goals”).

Dispositional proneness to pride. Gross and John (1997) developed the Berkeley Expressivity Questionnaire. The BEQ measures general emotional expressivity. We patterned our items after the BEQ but desired to measure specific individual differences in pride. Three items were developed (e.g., express what you think about pride, “Showing pride is a sign that one is successful”).

Adaptive selling and working hard. These two performance-related constructs have been used frequently by researchers studying salespeople and have consistently been demonstrated to have a positive impact on sales performance (e.g., Sujan et al., 1994). Adaptive selling was measured by 8 items which were introduced with the words [as a result of reading the scenario], I think that…” (e.g., “I am very flexible in the selling approach that I use”; see also Spiro & Weitz, 1990). Working hard was measured with 3 items, which were introduced with the words, “having felt pride [as a result of reading the scenario], I would tend to…” (e.g., “work long hours to meet my sales objectives”; see Sujan et al., 1994). Responses to the working hard items were recorded on 7-point, “not at all intense” to “extremely intense” scales.

Organizational citizenship behaviors. The measures of citizenship behaviors were taken from MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Fetter (1991). Civic virtue expresses the degree to which the employee participates actively in the everyday life of the organization and was measured with 3 items (e.g., “I attend functions that are not required, but that help the organization image”). Sportsmanship indicates the extent that an employee tolerates less than ideal circumstances without complaining and was measured with 4 items (e.g., “I always focus on what is going wrong with my situation, rather than the positive side of it”). Helping reflects the amount of aid provided to coworkers with work-related problems and was measured with two items (e.g., “I willingly give of my time to help others”). Courtesy captures the degree to which an employee takes into account the needs of coworkers and was measured by 3 items (e.g., “I consider the impact of my actions on others”).

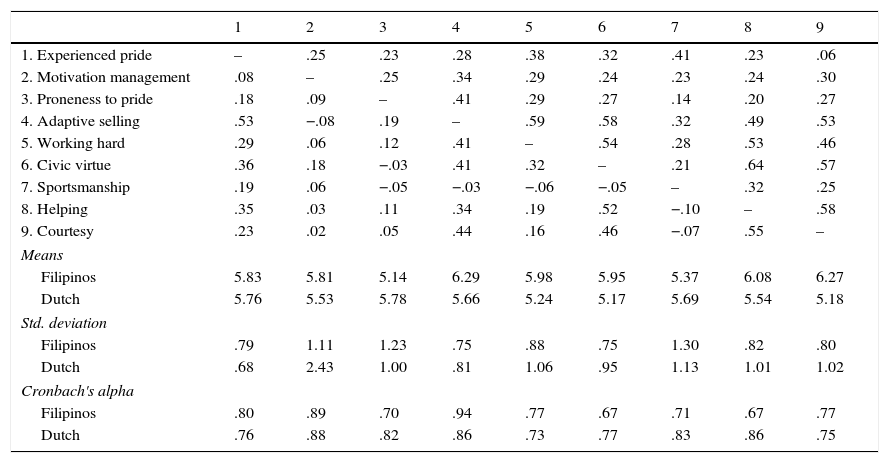

All items on the questionnaire can be found in Appendix. Table 2 presents correlations among scales, means, standard deviations, and Cronbach alpha values.

Correlations, means, standard deviations, and reliabilities of scales.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Experienced pride | – | .25 | .23 | .28 | .38 | .32 | .41 | .23 | .06 |

| 2. Motivation management | .08 | – | .25 | .34 | .29 | .24 | .23 | .24 | .30 |

| 3. Proneness to pride | .18 | .09 | – | .41 | .29 | .27 | .14 | .20 | .27 |

| 4. Adaptive selling | .53 | −.08 | .19 | – | .59 | .58 | .32 | .49 | .53 |

| 5. Working hard | .29 | .06 | .12 | .41 | – | .54 | .28 | .53 | .46 |

| 6. Civic virtue | .36 | .18 | −.03 | .41 | .32 | – | .21 | .64 | .57 |

| 7. Sportsmanship | .19 | .06 | −.05 | −.03 | −.06 | −.05 | – | .32 | .25 |

| 8. Helping | .35 | .03 | .11 | .34 | .19 | .52 | −.10 | – | .58 |

| 9. Courtesy | .23 | .02 | .05 | .44 | .16 | .46 | −.07 | .55 | – |

| Means | |||||||||

| Filipinos | 5.83 | 5.81 | 5.14 | 6.29 | 5.98 | 5.95 | 5.37 | 6.08 | 6.27 |

| Dutch | 5.76 | 5.53 | 5.78 | 5.66 | 5.24 | 5.17 | 5.69 | 5.54 | 5.18 |

| Std. deviation | |||||||||

| Filipinos | .79 | 1.11 | 1.23 | .75 | .88 | .75 | 1.30 | .82 | .80 |

| Dutch | .68 | 2.43 | 1.00 | .81 | 1.06 | .95 | 1.13 | 1.01 | 1.02 |

| Cronbach's alpha | |||||||||

| Filipinos | .80 | .89 | .70 | .94 | .77 | .67 | .71 | .67 | .77 |

| Dutch | .76 | .88 | .82 | .86 | .73 | .77 | .83 | .86 | .75 |

Note: Filipino correlations are above the diagonal; Dutch correlations are below.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to establish convergent and discriminant validity of the measures. The CFAs were done for the 3 emotional factors (i.e., experienced pride, motivation management, and proneness to pride), the 2 performance-related factors (i.e., adaptive selling and working hard), and the 4 citizenship behavior factors. The relatively small sample sizes prevented us from running a single CFA for all measures, which would have necessitated too many parameters to be estimated for the number of cases. Instead, we parceled items to form two indicators per factor as suggested by Bagozzi and Edwards (1998). The application of CFA was also used to establish factorial, measure, and reliability invariance across cultural samples before testing the main hypotheses. In this way, we establish the equivalence of measurement properties across cultures and rule-out differential reliability as a rival hypothesis.

To test the main hypotheses, multiple regressions with interactions were performed. All variables were mean centered, and the nature of the interactions was interpreted by use of procedures suggested by Jaccard and Turisi (2003, see Results).

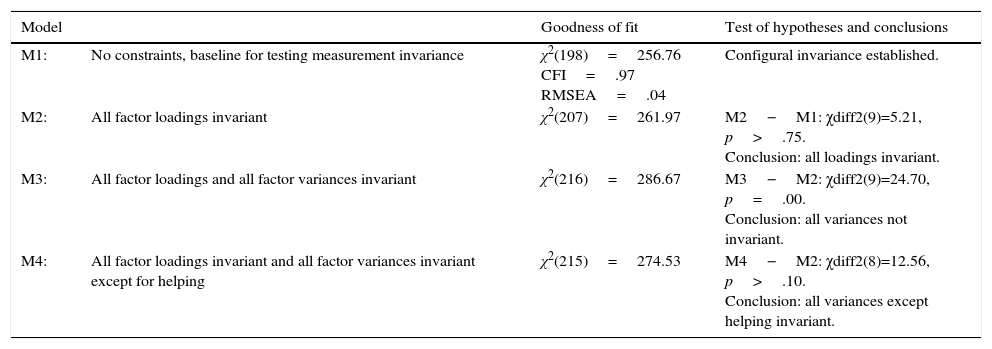

Table 3 summarizes the findings for tests of invariance. Model 1 (M1) demonstrates that configural invariance has been established. That is, the items load satisfactorily on hypothesized factors and the same 9 factors, corresponding to the 9 variables under study, result for the Filipino and Dutch respondents: χ2(198)=256.76, CFI=.97, and RMSEA=.04. Model 2 constrains the respective pairs of factor loadings to be equal across the Filipino and Dutch samples. The chi-square difference test shows that we cannot reject the hypothesis that the factor loadings are invariant across samples: χd2(9)=5.21, and p>.75. This means that the degree of correspondence between each indicator and its hypothesized factor is the same for Filipinos and Dutch respondents. Model 3 further hypothesizes that the factor variances are equal across samples. This hypothesis must be rejected: χd2(9)=24.70, and p>.00. An inspection of the findings suggested that perhaps only the factor variance for helping fails to be invariant. Indeed, Model 4 confirms that the variances of the 8 other factors are invariant across samples: χd2(8)=12.56 and p>.10. This finding, in conjunction with the finding of equal factor loadings, reveals that all scales show equal reliabilities for Filipinos and Dutch, except for helping. Nevertheless, the reliabilities for the helping measures were not too far apart for the Filipino (.67) and Dutch (.86) samples. In sum, the psychometric properties of the 9 scales are remarkably similar for Filipino and Dutch respondents, thereby providing a sound basis for testing the main hypotheses of the study, and ruling out differential reliabilities of measures of scales as rival hypotheses.

Tests of invariance of key parameters cross Dutch and Filipino samples.

| Model | Goodness of fit | Test of hypotheses and conclusions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1: | No constraints, baseline for testing measurement invariance | χ2(198)=256.76 CFI=.97 RMSEA=.04 | Configural invariance established. |

| M2: | All factor loadings invariant | χ2(207)=261.97 | M2−M1: χdiff2(9)=5.21, p>.75. Conclusion: all loadings invariant. |

| M3: | All factor loadings and all factor variances invariant | χ2(216)=286.67 | M3−M2: χdiff2(9)=24.70, p=.00. Conclusion: all variances not invariant. |

| M4: | All factor loadings invariant and all factor variances invariant except for helping | χ2(215)=274.53 | M4−M2: χdiff2(8)=12.56, p>.10. Conclusion: all variances except helping invariant. |

The nine-factor CFAs fit well in both samples. For the Filipinos, the results were χ2(99)=149.38, p=.00, CFI=.96, and RMSEA=.07. The factor loadings were all high and highly significant: pride (.72, .85), motivation management (.94, .84), proneness to pride (.84, .82), civic virtue (.74, .73), sportsmanship (.68, .81), helping (.92, .94), courtesy (.93, .62), adaptive selling (.97, .94), and working hard (.73, .86). The 9 factors correlated from −.08 to .72, and all were distinct. For the Dutch, the results were χ2(99)=107.39, p=.27, CFI=.99, and RMSEA=.03. The factor loadings were all high and highly significant: pride (.82, .84), motivation management (.87, .88), proneness to pride (.95, .80), civic virtue (.80, .83), sportsmanship (.81, .90), helping (.80, .93), courtesy (.77, .81), adaptive selling (.91, .90), and working hard (.55, .79). The 9 factors correlated from −.13 to .68, and all were distinct.

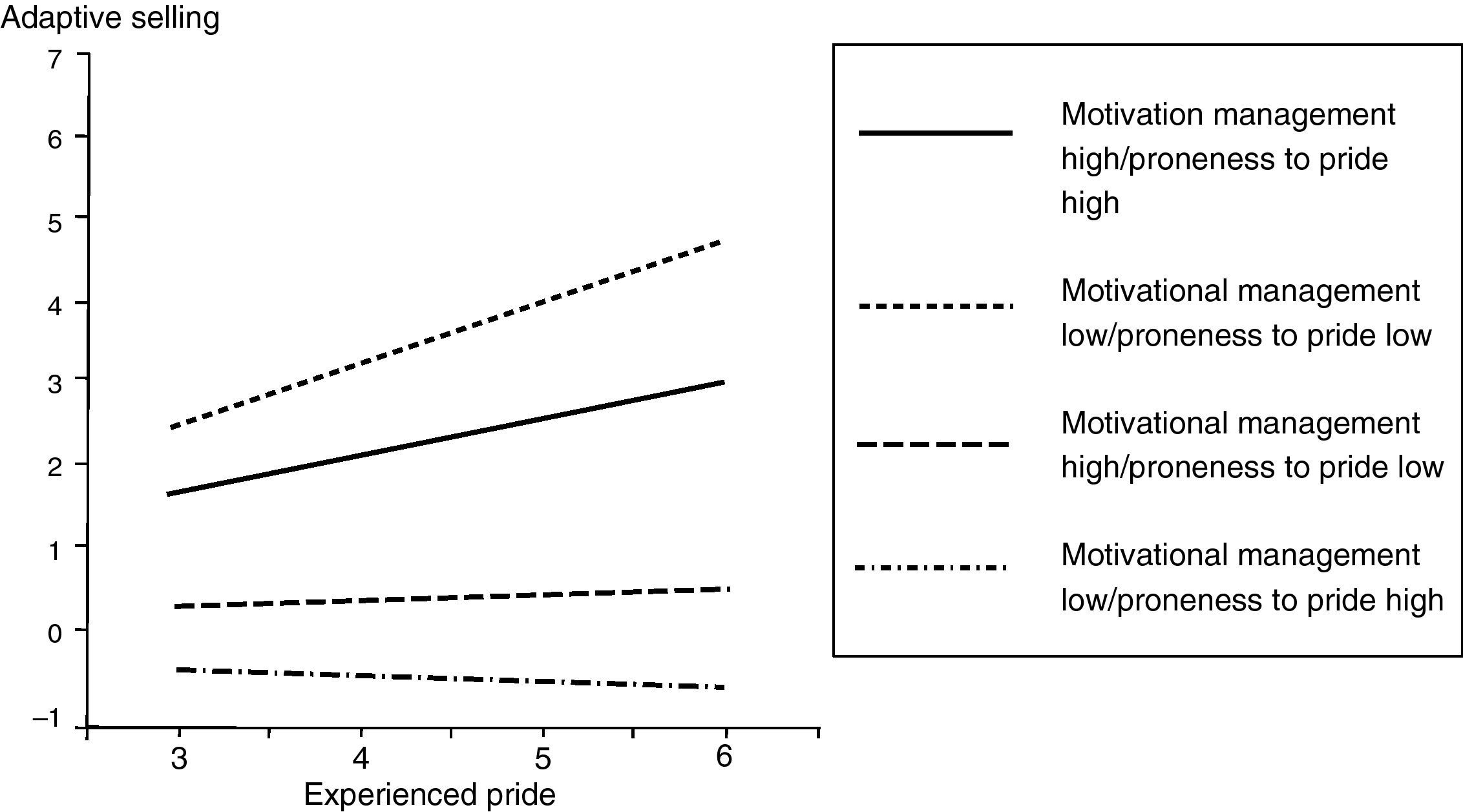

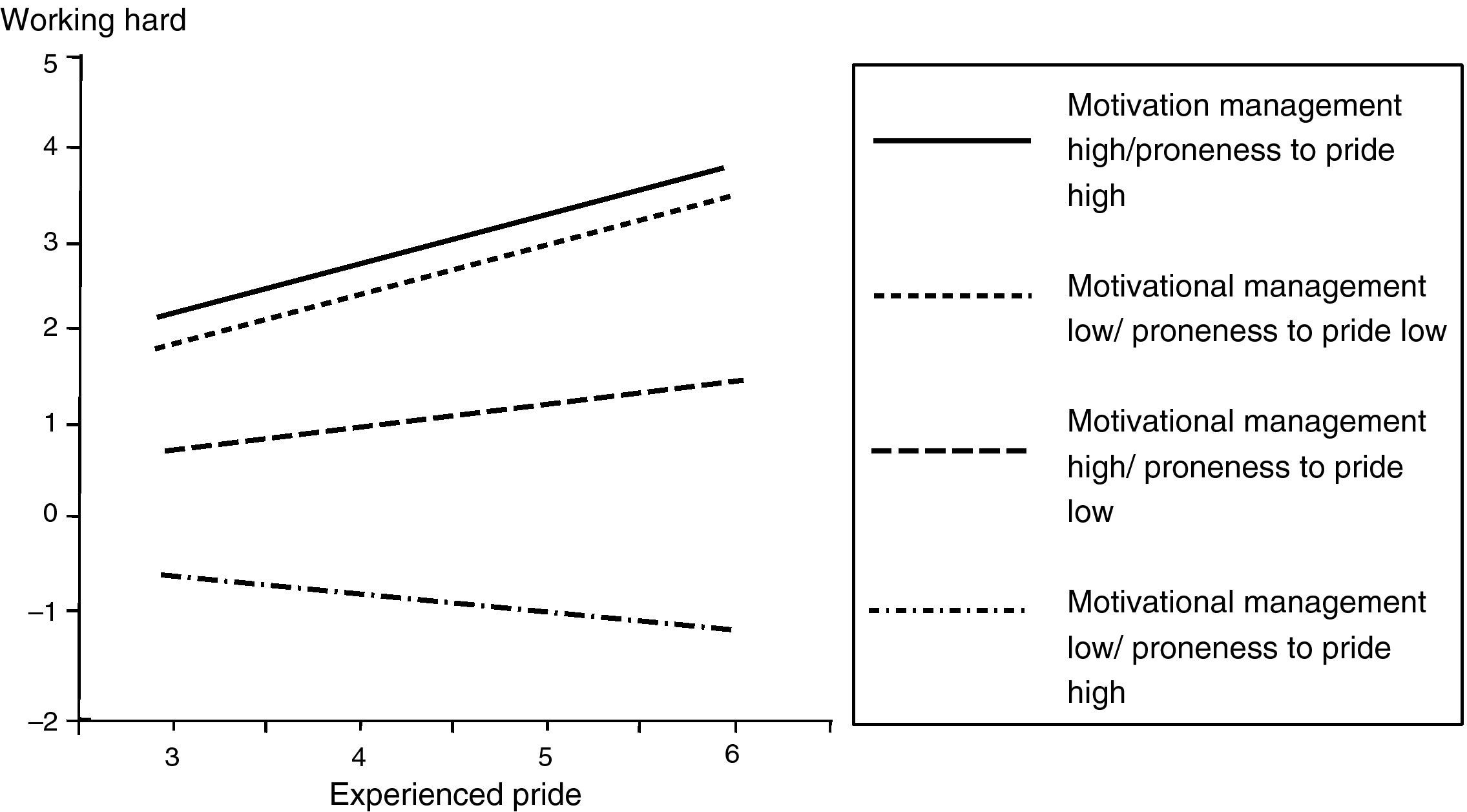

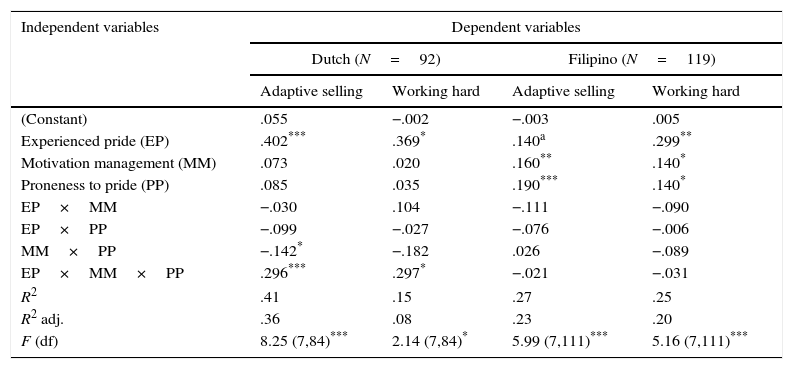

Test of hypothesesTable 4 presents the findings for the effects of experienced pride, motivation management, and proneness to pride on adaptive selling and on working hard. Looking first at the results for Dutch salespersons, and recalling that the effects of experienced pride were expected to be conditioned by levels of motivation management and proneness to pride, we see that the three-way interactions are significant for both adaptive selling (β=.30, p<.001) and working hard (β=.30, p<.05), as predicted.

Findings for the effects of experienced pride, motivation management, and proneness to pride on adaptive selling and working hard.

| Independent variables | Dependent variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch (N=92) | Filipino (N=119) | |||

| Adaptive selling | Working hard | Adaptive selling | Working hard | |

| (Constant) | .055 | −.002 | −.003 | .005 |

| Experienced pride (EP) | .402*** | .369* | .140a | .299** |

| Motivation management (MM) | .073 | .020 | .160** | .140* |

| Proneness to pride (PP) | .085 | .035 | .190*** | .140* |

| EP×MM | −.030 | .104 | −.111 | −.090 |

| EP×PP | −.099 | −.027 | −.076 | −.006 |

| MM×PP | −.142* | −.182 | .026 | −.089 |

| EP×MM×PP | .296*** | .297* | −.021 | −.031 |

| R2 | .41 | .15 | .27 | .25 |

| R2 adj. | .36 | .08 | .23 | .20 |

| F (df) | 8.25 (7,84)*** | 2.14 (7,84)* | 5.99 (7,111)*** | 5.16 (7,111)*** |

To interpret the three-way interactions, we used the procedure recommended by Jaccard and Turisi (2003) whereby the slopes for the effects of experienced pride on the dependent variables (i.e., adaptive selling and working hard) are estimated at different combinations of proneness to pride and motivation management. Specifically, we created four conditions under which to describe the slopes of the dependent variables on experienced pride: (1) a high value on motivation management and a high value on proneness to pride, (2) a low value on motivation management and a low value on proneness to pride, (3) a low value on motivation management and a high value on proneness to pride, and (4) a high value on motivation management and a low value on proneness to pride. The low and high values are defined as 1 SD below the sample means and 1 SD above the sample means of motivation management and proneness to pride, respectively.

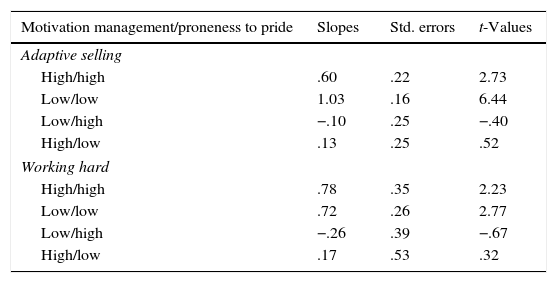

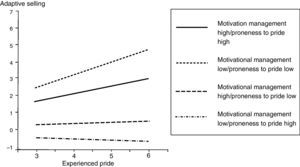

Table 5 shows the slopes and Figs. 1 and 2 present the plots of the regression lines for the different combinations of motivation management and proneness to pride by each dependent variable. It can be seen that the effects of experienced pride on adaptive selling and working hard are positive as hypothesized, when motivation management and proneness to pride concur or are in agreement (i.e., when motivation management and proneness to pride are both high or both low). But when motivation management and proneness to pride are out of phase or conflict (i.e., when motivation management is low/proneness to pride is high and when motivation management is high/proneness to pride low), experienced pride either has no effect or a slight negative effect, as forecast.

Slopes for the effects of experienced pride on adaptive selling and working hard as a function of motivation management and proneness to pride (Dutch employees).

| Motivation management/proneness to pride | Slopes | Std. errors | t-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive selling | |||

| High/high | .60 | .22 | 2.73 |

| Low/low | 1.03 | .16 | 6.44 |

| Low/high | −.10 | .25 | −.40 |

| High/low | .13 | .25 | .52 |

| Working hard | |||

| High/high | .78 | .35 | 2.23 |

| Low/low | .72 | .26 | 2.77 |

| Low/high | −.26 | .39 | −.67 |

| High/low | .17 | .53 | .32 |

Looking next at the results for the Filipino salespersons, in Table 4, and recalling that we expected main effects for experienced pride on adaptive selling and working hard, we see that the two- and three-way interactions are indeed non-significant, and only main effects result. On adaptive selling, experienced pride (β=.14, p<.06), motivation management (β=.16, p<.01), and proneness to pride (β=.19, p<.001) had positive effects. On working hard, experienced pride (β=.30, p<.01), motivation management (β=.14, p<.05), and proneness to pride (β=.14, p<.05) also had positive effects. That is, the effects of experienced pride on the dependent variables are not conditioned by motivation management and proneness to pride for Filipinos; rather, the latter variables add to adaptive selling and working hard, along with the effects of experienced pride as main effects.

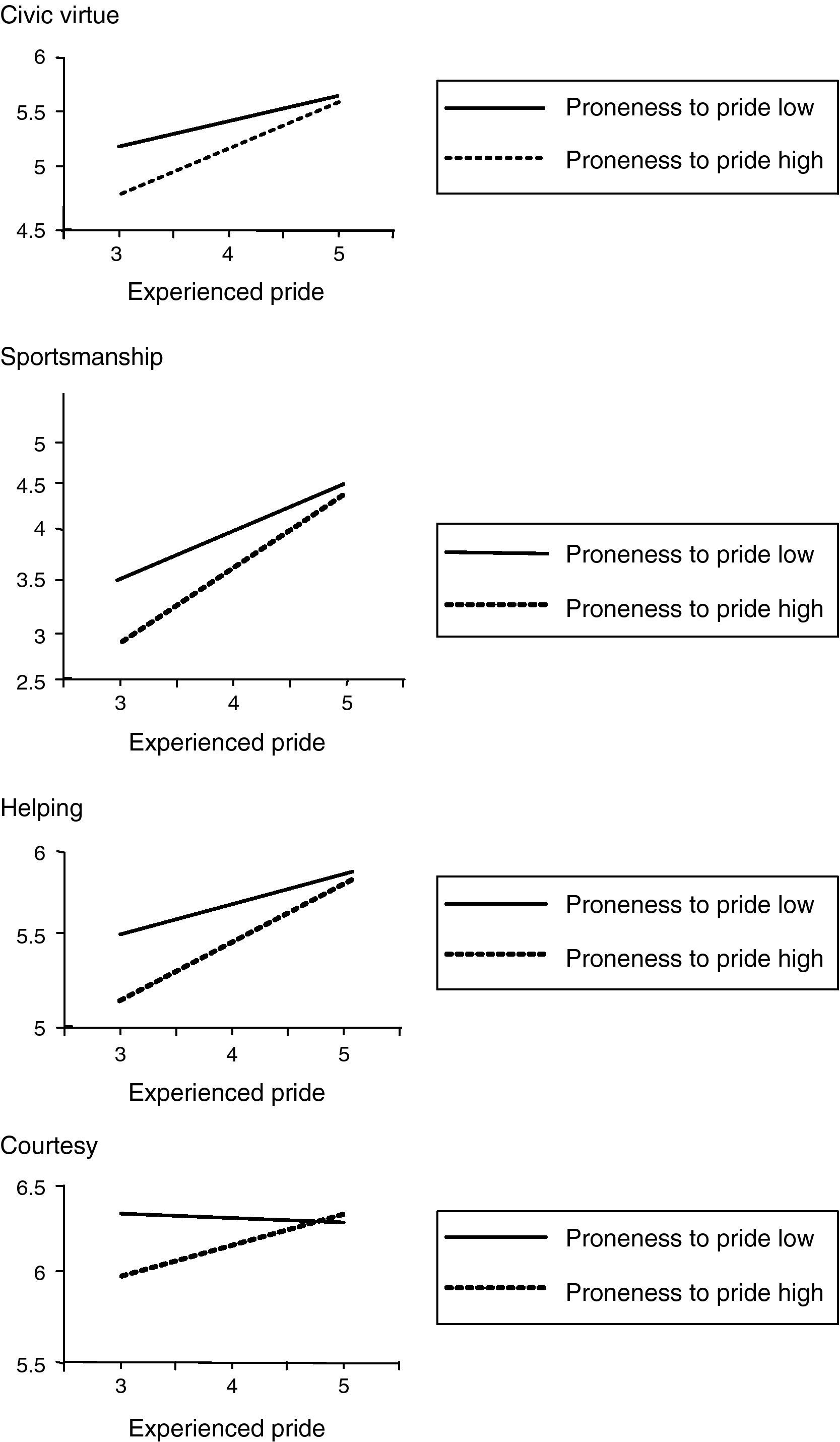

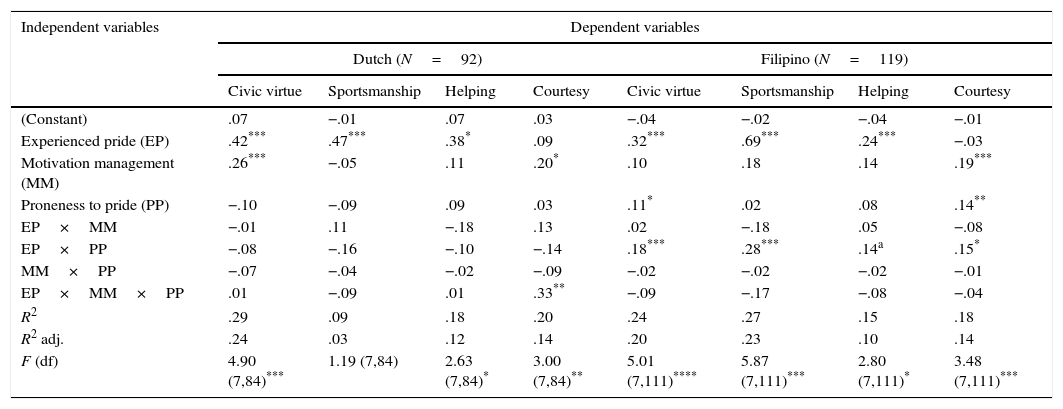

Table 6 shows the results for the effects of experienced pride, motivation management, and proneness to pride on organizational citizenship behaviors. Looking first at the findings for Dutch salespersons, and recalling that only experienced pride was expected to influence citizenship behaviors and was predicted to do so as main effects, we see that experienced pride indeed positively affects civic virtue (β=.42, p<.001), sportsmanship (β=.47, p<.001), and helping (β=.38, p<.05). Experienced pride does not have an overall main effect on courtesy (β=.09) but does have an effect on courtesy through its interaction with motivation management and proneness to pride (β=.33, p<.001).

Findings for the effects of experienced pride, motivation management, and proneness to pride on company citizenship behaviors.

| Independent variables | Dependent variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch (N=92) | Filipino (N=119) | |||||||

| Civic virtue | Sportsmanship | Helping | Courtesy | Civic virtue | Sportsmanship | Helping | Courtesy | |

| (Constant) | .07 | −.01 | .07 | .03 | −.04 | −.02 | −.04 | −.01 |

| Experienced pride (EP) | .42*** | .47*** | .38* | .09 | .32*** | .69*** | .24*** | −.03 |

| Motivation management (MM) | .26*** | −.05 | .11 | .20* | .10 | .18 | .14 | .19*** |

| Proneness to pride (PP) | −.10 | −.09 | .09 | .03 | .11* | .02 | .08 | .14** |

| EP×MM | −.01 | .11 | −.18 | .13 | .02 | −.18 | .05 | −.08 |

| EP×PP | −.08 | −.16 | −.10 | −.14 | .18*** | .28*** | .14a | .15* |

| MM×PP | −.07 | −.04 | −.02 | −.09 | −.02 | −.02 | −.02 | −.01 |

| EP×MM×PP | .01 | −.09 | .01 | .33** | −.09 | −.17 | −.08 | −.04 |

| R2 | .29 | .09 | .18 | .20 | .24 | .27 | .15 | .18 |

| R2 adj. | .24 | .03 | .12 | .14 | .20 | .23 | .10 | .14 |

| F (df) | 4.90 (7,84)*** | 1.19 (7,84) | 2.63 (7,84)* | 3.00 (7,84)** | 5.01 (7,111)**** | 5.87 (7,111)*** | 2.80 (7,111)* | 3.48 (7,111)*** |

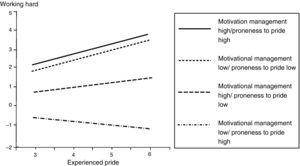

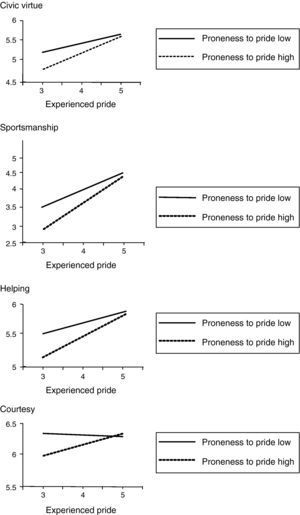

Looking next at the findings for the Filipino salespersons, and recalling that the effects of experienced pride and proneness to pride were expected to interact to influence citizenship behaviors, we see that the interactions between experienced pride and proneness to pride are indeed significant, but that the interactions between experienced pride and motivation management and the three-way interactions are non-significant, as expected. That is, the interaction for civic virtue, sportsmanship, helping, and courtesy are, respectively, β=.18, p<.001, β=.28, p<.001, β=.14, p<.07, and β=.15, p<.05. The nature of the two-way interactions can be interpreted by inspecting Fig. 3, where we have again followed the procedure recommended by Jaccard and Turisi (2003). In each case, it can be seen that the effects of experienced pride on organizational citizenship behaviors increase faster when proneness to pride is high versus low.

DiscussionThe findings establish that pride is an important determinant of motivational and behavioral responses of salespersons. This was found to be so for the relationships of boundary spanners with both customers and with coworkers. Such findings confirm and complement other studies in selling that found that positive emotions play a key roles guiding selling behavior (Dixon & Schertzer, 2005; Palmatier, Jarvis, Bechkoff, & Kardes, 2009). However, the precise functioning of pride was shown to be governed by dynamic self-regulation; specifically, by motivation management and proneness to pride, whose effects are further conditioned by cultural requisites. As Erevelles and Fukawa (2013, p. 16) note, cross cultural studies of emotions in selling are scarce and our research addresses an important gap here.

Pride is one of the few positive, self-conscious emotions common in social situations (Tangney, 2003), and is closely linked with self-esteem (Lazarus, 1991, p. 441). By itself, pride functions to motivate action and achievement (e.g., Lewis, 2000; Stipek, Recchia, & McClintic, 1992) and more specifically to energize, orient, and select behavior (Biernat, 1989). Fredrickson and Branigan (2001, p. 143) elaborate on this theme by suggesting that the “thought-action tendency” for pride covers three characteristics: “physical expansiveness (e.g., …bursting with pride)…”, “the urge to share the news or event…with others,” and “the urge to envision even greater achievements”. Fredrickson and Branigan (2001, p. 143) further claim that pride broadens one's mindset, helps people “set and prioritize their goals for the future”, and “fuels achievement motivation”. Our study confirms some of these predictions but only under certain conditions. That is, Dutch salespeople were found to self-regulate their pride so as to avoid hubris. Greater felt pride led to greater adaptation and working hard but only to the extent that employees engaged in motivation management and mitigated the damaging consequences of hubris in their relationships with customers. By contrast, in their relationships with colleagues, Dutch employees performed more company citizenship behaviors, the greater their experienced pride. Experienced pride had direct, main effects, and was not conditioned by motivation management when Dutch employees interact with colleagues.

It seems reasonable to conclude that the Dutch, who exhibit an independent self-construal and are strongly individualistic, use the occasion of helping colleagues as a way to express their pride publicly and standout. This interpretation is consistent with the emotional syndrome description of North American and Western European cultures, where Mascolo et al. (2003, p. 379) characterize the personal function of pride as strengthening the sense of “personal worth, efficacy, and value in the eyes of others” and the social function of pride as alerting others of “self's accomplishment and value”. Impression management thus constitutes an important motivational force (Bolino, 1999).

Experienced pride has quite different effects for Filipinos, who exhibit an interdependent self-construal and are strongly collectivistic. Greater felt pride was found to directly influence adaptive selling and working hard when Filipinos interact with customers. Instead of a self-regulation of pride, per se, by motivation management modulating the effects of experienced pride on adaptability and effort, it appears that Filipino salespersons transform or sublimate their felt pride directly into personal strivings that are functional for increasing sales. A regulation of these effects of pride does not seem to be necessary as the affected behaviors are customer-oriented and facilitate reciprocal exchange, i.e. they are in alignment with cultural business norms. Hence, the main effects of experienced pride occur. This sublimation is done within a formal hierarchical relationship where the dependence and lower status of the customer boundary spanner on the customer are strictly acknowledged by both parties.

Nevertheless, it is not the case that motivation management of felt pride is forgone by Filipinos when dealing with customers. Indeed, the findings show that motivation management functions as a main effect on adaptive selling and working hard, along with experienced pride. Manifestations of hubris, if any, need to be squelched by members of interdependent cultures, and self-regulatory actions employed to avoid hubris in impression management (Bolino, 1999; Bonanno, 2001; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). These positive feelings, in turn, promote further customer-oriented, reciprocal behaviors and hence stimulate the use of adaptive resources and working hard (Fredrickson, 2001). In other words, motivation management does not moderate the influence of experienced pride but rather shows compensatory or additive effects. Unlike the contingent effects found for Dutch salespersons–customer relationships, either experienced pride or motivation management, or both experienced pride and motivation management, influence adaptive selling and working hard as independent effects for Filipinos.

To the observed self-regulatory and cultural processes found in our study, we should mention the role of the individual difference variable, dispositional proneness to pride. This variable also had complex effects. For the Dutch, proneness to pride served to moderate the effects of experienced pride, in conjunction with motivation management, to influence adaptive selling and working hard. Pride only had positive effects on adaptive selling and working hard when both moderating variables concurred or were in agreement (i.e., when both were high or both were low). When motivation management was high, while proneness to pride was low, experienced pride became down-regulated and its expression further reduced, and, as a result, it had no impact on adaptive selling behaviors or working hard. Similarly, when motivation management was low, while proneness to pride was high, experienced pride became amplified and risked turning into hubris, with a negative effect on adaptive selling and working hard as a result. The impact of proneness to pride is an instance of what Gross (2002; see also Gross et al., 2000) terms, response modulation of emotions. But here, instead of an explicit strategic orientation, as found in the self-regulation by motivation management, it is one's disposition in the form of a personality trait that modulates the effects of experienced pride.

Dispositional proneness to pride also functions as a moderator for Filipinos, but in this case with respect to the effects of experienced pride on company citizenship behaviors when relating to colleagues. Here one helps colleagues more, the greater the proneness to feel pride. The performance of citizenship behaviors promotes fitting in with colleagues and allows the employee to be self-effacing about personal success, while at the same time celebrating the group's success and publicly acknowledging the mutual support and interdependence that all share as coworkers. This entails corresponding implementation of appropriate impression management tactics (Bolino, 1999). In contrast, proneness to pride functions as main effects when Filipino employee interacts with customers. Here proneness to pride, like experienced pride, becomes sublimated so as to fulfill one's role as a salesperson in a position of dependence on the customer.

We thus see that emotion regulation depends very much on culture and results in quite different outcomes for the Dutch and Filipino salespeople. These differences stem from the distinct self-concepts (Markus & Kitayama, 1991) and the corresponding distinct display rules (Keltner, Ekman, Gonzaga, & Beer, 2003) and impression management behaviors (Bolino, 1999) associated with the cultures.

The overall picture emerging from this study can perhaps be best interpreted from Bonanno's recent research on emotional homeostasis (Bonanno, 2001; Westphal & Bonanno, 2004). Bonanno proposed that the suppression or enhancement of emotional expression is done in order to optimize the consequences of emotional responses for one's personal goals with respect to idealized self-images or other desired subjective states. Emotional expressions that are perceived to lead to negative social consequences are suppressed, whereas those that lead to positive social consequences are enhanced. When and how suppression and enhancement occur depends on the self-construal characteristic of one's cultural background, the nature of the social relationships one has, and individual differences. We thus found that experienced pride was suppressed by Dutch salespersons interacting with customers (as a function of self-regulation) and was enhanced by Filipino salespersons interacting with colleagues (as a consequence of the individual difference, proneness to pride). These suppression and enhancement effects are instigated such that discrepancies between the idealized self-images and the actual emotional experience or expression are minimized; they are therefore called closed-loop or negative feedback systems (e.g., Davis, 1979). The main effects for experienced pride, motivation management, and proneness to pride found in our study are indicative of open-loop systems where ingrained emotional responses or learned strategic repertoires operate automatically to initiate certain behaviors. In particular, depending on the culturally induced self-construal, and the nature of the social relationship the salesperson had (either hierarchical or egalitarian), experienced pride, motivation management, and proneness to pride instigated adaptation, working hard, and/or initiations organizational citizenship behaviors in direct, non-moderated ways.

We are moving into an era where (a) many firms operate internationally, (b) salespeople are hired within firms coming from different nations and cultures and are expected to work together in sales teams, and (c) migration of people and firms is occurring across the globe. Therefore in one and the same firm it is likely that salespeople from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds operate (Lassk, Ingram, Kraus, & Mascio, 2012). In fact, firms these days seek people with diverse cultural backgrounds as a matter of policy (McGuire & Bagher, 2010). Recent research demonstrates too that sales people and their managers require certain skills in social intelligence (Verbeke, Belschak, Bakker, & Dietz, 2008), emotional wisdom (Bagozzi, Belschak, & Verbeke, 2010), and emotional intelligence (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000), but more and more as well in cultural intelligence (Earley & Ang, 2003) or cultural diversity skills (Bush & Ingram, 2001). Firms make huge investments in training their sales forces, for example, and it is quite challenging to comprehend let alone train salespeople from diverse cultural backgrounds (Lassk et al., 2012). A key idea in our article is that salesperson's self-construal (independent vs. interdependent) affects the way they self-regulate their emotions, and these self-construals are learned culturally at a young age and therefore are difficult (if not impossible) to modify. Sales trainers and managers need to understand different self-construal's that their salespeople possess and take these into account to help salespeople cope with their emotions as they play out in interactions with customers.

As above-mentioned in both countries (the Netherlands and the Philippines), pride is an important driver of both sales performance and citizenship behaviors. Therefore it is important for managers to instill pride in their salesforce as it has broaden-and-build effects on other emotions (Fredrickson, 2001), which makes people more adaptive during customer interactions and also motivates them to engage in citizenship behaviors. Managers should therefore instill pride in the salesforce as much as possible, which is most easily done by reinforcing company pride (Gouthier & Rhein, 2011). Equally, sales managers should recognize outstanding performance and publicly announce better performing salespeople (Gouthier & Rhein, 2011). However, as caveat, salespeople and managers should monitor pride and regulate it so that it does not turn into excessive pride (hubris), which can lead to breakdowns in communication and make customers feel uncomfortable.

LimitationsAlthough the findings are consistent with the theoretical arguments of the extant literature on pride, we acknowledge some limitations of the current research. First, our findings are based on self-report measures. Ideally, objective performance measures rather than motivation should be obtained in the future. Meta-analyses, however, suggest that subjective outcome measures are reliable and valid in the personal selling area (Churchill, Ford, Hartley, & Walker, 1985). Second, using a cross-sectional design makes it impossible to draw conclusions about causality. It might be possible, for instance, that highly motivated salespersons experience more pride as a reaction to being praised by their manager. Experimental or longitudinal designs would help clarify questions about causality. In this regard, research is needed to strengthen the interpretation of our findings. Finally, another shortcoming to mention is the difference in education of salespeople in the Netherlands and the Philippines, where 18% of the former and 56% of the latter were university educated. Although the percentages are roughly characteristic of both countries and reflect practices therein, it is not known whether such differences could account for our findings.

Future researchIn our study we investigated the effect of the self-regulation of the self-conscious emotion, pride, and its effects on performance in a cross-cultural setting. An interesting question for future research would be to explore the self-regulation of other self-conscious emotions such as shame, guilt, envy, or embarrassment across cultures. These may invoke different self-serving and other motives (Bolino, 1999). The literature on cross-cultural psychology argues that the experience and self-regulation of self-conscious emotions in particular should vary across cultures because of different cultural self-construals (Kitayama, Markus, & Matsumoto, 1995). Existing research on shame in an independent versus interdependent culture suggests that similar differences might be expected for pride (Bagozzi, Verbeke, & Gavino, 2003).

The findings of our study indicate that pride is regulated differently and differentially affects performance in independent versus interdependent cultures. Much less research is available though on the effects of other cultural values such as power distance (Hofstede, 2001), equality, competitiveness, helping behavior values, work versus family conflicts, and mentoring practices. In this regard, it would be interesting for future research to investigate the effects and self-regulation of emotions across two or more interdependent cultures that differ on other dimensions of culture: for instance, the Philippines (power distance=94) versus South Korea (power distance=60). Also as one reviewer of our paper recommended, it would be informative to compare an independent-based country, such as the Netherlands (power distance=38), to a country in Latin American, say, such as Mexico (power distance=81). By doing so, as well as between two or more independent-based cultures and between interdependent and independent-based cultures, we then could better study the full interactions between situation, individual, and culture.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors wish to thank two reviewers for comments made on a draft of the paper that helped us prepare a better paper.

“During your three-month feedback with your sales manager at your organization, (s)he tells you that you did excellent work. (S)he tells you that you performed better that most salespeople and that you now belong to the top 10 percent of salespeople. This will be mentioned in the next edition of your organization's newsletter that is being sent to all of your customers. In addition many of your colleagues already have congratulated you.

Having read this scenario, please indicate to what extent the following sentences apply to you.”

Independent variables

Experienced Pride

Now I know quite well what I have to do to be a good salesperson.

Now I have the self-assurance needed to reach my sales quota.

I am now convinced that I can persuade my customers to buy from me.

During such moments, what other feelings and thoughts emerge?

I think that I am a happy salesperson.

I think that I am a satisfied salesperson.

I think that I am a self-assured salesperson.

Motivation Management

I try not to get too self-satisfied so that I am able to keep on performing.

I try not to get too self-assured so that I am able to keep striving for higher goals.

I try not to get too self-satisfied so that I do not get overconfident.

Dispositional Pride

Showing pride is a sign that one is successful.

Feeling proud is a way of expressing that one is happy.

People have the right to express their pride.

Dependent Variable Measures

“Now that you have experienced pride in the scenario, how do you feel and what actions do you intend to do?”

Working Hard

I work long hours to meet my sales objectives.

I do not give up easily when I encounter a customer who is difficult to sell.

I work untiringly at selling to a customer until I get an order.

Adaptive Selling

I vary my sales style from situation to situation.

I easily use a wide variety of selling approaches.

I provide a unique approach to each customer as required.

I am very sensitive to the needs of my customers. I easily modify my sales presentation if the situation calls for it.

I am very flexible in the selling approach I use.

I consider how one customer differs from another.

I feel confident that I can change my planned presentation when necessary.

Organizational Citizenship Behaviors

(Civic Virtue)

I “keep up” with developments in the organization.

I attend functions that are not required, but that help the organization image.

I read and keep up with the organization's announcements, messages, memos, etc.

(Sportsmanship)

I consume a lot of time complaining about trivial matters.

I make problems bigger that they are.

I always focus on what is going wrong with my situation, rather that the positive side of it.

I always find fault with what the organization is doing.

(Helping)

I help orient new colleagues even though it is not required.

I am always ready to help or to lend a helping hand to those around me.

I willingly give of my time to help others.

(Courtesy)

I respect other people's rights to common/shared resources (including clerical help, materials, etc.).

I consider the impact of my actions on others.

I “touch base” with others (inform them in advance) before initiating actions that might affect them.

I try to avoid creating problems for others.

R.P. Bagozzi is the Dwight F. Benton Professor of Behavioral Science at the Ross School of Business, University of Michigan. Professor Bagozzi does research into human emotions and their role in organizations and consumer behavior, as well as biological bases of management.

F.D. Belschak is Associate Professor at the Amsterdam School of Business, University of Amsterdam. His research interests lie in organization behavior, citizenship behavior, and organizational ethics.