The focal action in CSR campaigns can be either related or unrelated to the company's core business. Previous research has revealed mixed results as to which option produces the most favorable consumer responses. In this paper, we try to shed some light on the effect of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business on consumer response, while identifying skepticism toward CSR as the key moderator that can help us assess its impact. The data confirm our hypotheses and clarify the role of congruence in CSR initiatives. Both academic and managerial implications are reported and discussed.

La actividad central de las campañas de RSC puede estar relacionada o no con la actividad principal de la empresa. La literatura previa ha obtenido resultados no concluyentes en cuanto a qué alternativa genera las respuestas más favorables en los consumidores. En este trabajo, se aporta evidencia sobre el efecto de la congruencia entre las acciones de RSC y la actividad principal de la empresa en la respuesta del consumidor, al tiempo que se identifica el escepticismo hacia las acciones de RSC como el moderador clave para entender el impacto de la congruencia. Los datos confirman nuestras hipótesis acerca del efecto de la congruencia de las iniciativas de RSC. Al final de este trabajo se discuten las implicaciones para la literatura de RSC y para la gestión de la empresa.

The question that arises today is no longer whether companies should invest their resources and time on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives, but how and when they can create a significant impact on consumers through investment in social initiatives. CSR initiatives have moved from being an option to being perceived as an activity to be performed in order to improve the results of the company, not only in the short term, but also with regard to long-term relationships (Porter & Kramer, 2006). The main reason behind this new perception and role of CSR activities is that consumers’ expectations have changed. As revealed by the 2013 Cone Communications/Echo Global CSR Study, 94% of consumers believe that companies should go beyond the economic performance and play an important role in improving social and environmental welfare, which is known as triple bottom line.

Every day more companies implement initiatives to improve public health, safety, the environment or welfare of the community, with examples of well-known companies such as Primark, Ikea or Coca Cola Company. Since its partnership with BSR (Business for Social Responsibility) in 2011, Primark is working on the project Health Enables Returns to improve the quality of life of its employees in factories in Bangladesh, providing tools (training on maternal health, personal hygiene and diseases such as AIDS, malaria and dengue fever) that enable women to have greater control over their personal and work life. Ikea has developed the initiative People+Planet, through which they aim to have a positive impact on both individuals and the environment. And since 2005, Coca Cola has partnered other organizations in 86 countries to support local water conservation initiatives.

When companies engage in CSR, consumer's attitude toward the company is positively reinforced through better assessments of the company and its products (Barone, Miyazaki, & Taylor, 2000; Bhattacharya & Sen, 2004; Brown & Dacin, 1997; Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001). However, the study of the relationship between CSR and consumer behavior is relatively recent, which at least partly explains the lack of a generally accepted model of consumer responses to CSR initiatives. Research has shown that CSR campaigns influence buying behavior in a more ethical direction only if it is convenient and there is no extra cost in terms of increase in price or quality loss (Carrigan & Attalla, 2001). Additionally, while negative information on CSR affects all consumers, only those truly motivated toward social behavior are affected by corporate initiatives related to the welfare of society (Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001). Therefore, further investigation is needed to shed light on the differential responses consumers show when exposed to such initiatives.

One of the key factors that affect the way consumers respond to CSR is related to the congruence between the social initiative and the main activity of the company (Becker-Olsen, Cudmore, & Hill, 2006; Bigné, Currás-Pérez, & Sánchez-García, 2009; Bigné, Currás-Pérez, & Aldás-Manzano, 2012; Webb & Mohr, 1998). Previous literature has reported mixed results with respect to the activities on which a company must focus when investing in CSR. First, there is evidence suggesting that in certain situations where the company develops CSR activities, consumers infer a selfish motivation when business and causes are linked, while real altruistic behavior is attributed when the activity of the company and the social cause are not related (Ellen, Mohr, & Webb, 2000; Moosmayer & Fulhjan, 2013). However, another stream of research states that results are better for campaigns where the social initiative and the main activity of the firm are congruent (Dean, 1999; Lee & Jeong, 2014; Lucke & Heinze, 2015; Speed & Thompson, 2000).

In this paper, we resume the influence of congruence on CSR associations, instead of focusing on attitude, as the former represents the immediate consumers’ reactions to the campaign. Additionally, the lack of consensus with regard to the effect of congruence on consumers’ responses lead us to believe that such congruence is not enough to explain consumers reactions to CSR initiatives. There must be other variables able to explain why this effect is positive in some studies and negative in others. We propose that skepticism is the variable that can clarify the results found so far. Skepticism has previously been studied in literature and defined as the person's tendency to doubt, disbelieve, and question (Boush, Friestad, & Rose, 1994; Forehand & Grier, 2003). In the context of CSR initiatives, individuals can be more or less skeptical depending on their inferences about the firm motives to engage in such action. Thus, skepticism toward CSR refers to whether the consumer attributes CSR campaigns to egoistic-driven motives or public-serving motives (Skarmeas & Leonidou, 2013).

The goal of this paper is twofold. First, we analyze the effect of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business on CSR associations. Second, we incorporate CSR skepticism as a moderator in the relationship and as a key construct to shed light on the lack of consensus previously stated in literature. The structure of the paper is as follows. First, we review the relevant literature and propose a set of hypotheses. Then, the methodology is presented. Next, the results are reported and, finally, both theoretical and managerial contributions are discussed.

Literature reviewCSR and consumer behaviorThe existence of more than forty definitions of CSR (Dahlsrud, 2008) proves the lack of consistency in terms of both conceptualization and measurement. CSR was initially approached from the perspective of management and later marketing scholars started to analyze the phenomenon from the consumers’ point of view (Brown & Dacin, 1997; Ellen et al., 2000; Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001). This marketing approach has primarily focused on two key aspects. On the one hand, the operationalization of the CSR to influence consumers’ perceptions about the social responsibility of the company (Aguinis & Glavas, 2013; Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003). One way companies have operationalized CSR has been through the creation of a connection with a cause, which is properly called cause-related marketing (CRM) and defined as “the process of formulating and implementing marketing activities that are characterized by an offer from the firm to contribute a specified amount to a designated cause when customers engage in revenue-providing exchanges that satisfy organizational and individual objectives” (Varadarajan & Menon, 1988). Another way to shape CSR has been through advertising campaigns with the aim of increasing consumer awareness about their initiatives, the so-called advocacy advertising, defined as “a competitive business tool that marketers and organizations use to affect public opinion and create an environment more favorable to their position” (Haley, 1996). Traditionally, governments and NGO's have used these ads to highlight their issues of concern. With these campaigns, marketers seek to create and maintain a long-term relationship with the customer, which results in benefits related to reputation and trust on the company. Thus, consumers interpret the behavior from the firm as dedicated not only to their own interest, but also to society (Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001).

On the other hand, literature has also dealt with the way in which perception of CSR affects consumers’ responses, that is, how companies’ social behavior affects cognitive, emotional and behavioral consumer responses (Becker-Olsen et al., 2006; Forehand & Grier, 2003; Webb & Mohr, 1998). CSR initiatives may have an effect on attitude toward the company and its products (Brown & Dacin, 1997; Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001), brand reputation (Brammer & Millington, 2005), credibility of the organization (Lafferty & Goldsmith, 2005), resilience to negative information about the company (Peloza, 2006), positive word of mouth (Hoeffler & Keller, 2002), identification with the organization (Marín & Ruiz, 2007; Marín, Ruiz, & Rubio, 2009; Ruiz & Marín, 2008; Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001), purchase intention (Du, Bhattacharya, & Sen, 2007; Mohr & Webb, 2005) and willingness to pay more for socially responsible products (Laroche, Bergeron, & Barbaro-Forleo, 2001). In sum, the extent to which CSR initiatives are perceived as central, distinct and enduring may contribute to the promotion of the company, brand reputation, brand image and, therefore, to more positive evaluations (Bhattacharya, Hayagreeva, & Glynn, 1995).

As a result of CSR initiatives, associations between the company and the social cause to which it relates can be created, influencing brand perceptions. It is well known that “the power of a brand depends on what consumers have learned, felt, seen and heard about the brand as a result of their experiences over time, that is to say, depends on what lies on the consumers’ mind” (Hoeffler & Keller, 2002). Therefore, associations derived from CSR may affect consumers’ responses to the brand. In consumer behavior literature, corporate associations have been defined as all information a person accrues about a company. These associations can be divided into two categories: corporate abilities associations, which refer to the firm experience in producing and delivering its products or services and, corporate social responsibility associations (CSR associations), which reflect the status of the organization and its activities with regard to its perceived societal obligations (Brown & Dacin, 1997). Through the empirical study proposed in this research, CSR associations act as a mediator between congruence in social initiatives of firms and behavioral variables.

Congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core businessResearch on consumer response to the firms’ social behavior serves as a guide for companies to properly choose the social cause they allocate their investments in. The way managers use their CSR initiatives to position the company in the market is important, as it helps consumers understand how companies generate a point of differentiation in a competitive environment, reduce uncertainty about the company's business and its products and increase purchase intention (Du et al., 2007). In that vein, how consumers perceive the relationship between the CSR initiative and the firm's core business could determine their responses and it is known as “congruence”. Based on Sen and Bhattacharya (2001), congruence is defined as the amount of overlap consumers perceive between the CSR campaign and the company's core business.

One stream of research found in literature has related congruence with cause-related marketing activities. This contribution is based on the Persuasion Knowledge Model and the main idea that consumers use the information available about companies’ attempts to persuade them to infer the reasons that lead the company to carry out such activity (Friestad & Wright, 1994). The amount of knowledge they retain affects consumer's thoughts regarding the underlying interests of business and, therefore, the effectiveness of marketing strategies. In that sense, Webb and Mohr (1998) found evidence that consumers value social initiatives performed outside the company's main scope more positively. The underlying reason is that they interpret that the motivations are linked to the welfare of society and not focused on the benefits. In the same direction, Barone et al. (2000) showed that consumers prefer an association with an altruistic motivation over a similar company whose purpose expresses a selfish motivation. Additionally, Nan and Heo (2007) showed that a cause-related marketing campaign with high congruence, compared to a cause-related marketing campaign with low congruence, is not more effective. However, although no positive effect emerged, no negative influence was confirmed either. However, these findings may be affected by the fact that they focus on cause-related marketing, because they imply that consumers are exposed to “an offer from the firm to contribute a specified amount to a designated cause when customers engage in revenue-providing exchanges that satisfy organizational and individual objectives” (Varadarajan & Menon, 1988). In other words, the negative effects of congruence may be due to the association of the contribution to the social cause with a purchase. In addition, cause-related marketing falls into the larger class of CSR programs (Robinson, Irmak, & Jayachandran, 2012). Consequently, the results of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business may be different to those found with cause-related marketing activities.

On the other hand, a second stream of research supports the positive relationship between congruence and consumers’ responses. This research is based on the Theory of Associative Networks (Bower, 1981) and has been primarily applied to analyze the effects of sponsorship activities. This theory states that high levels of consistency in the perceived relationship between the event and the company sponsoring improve the attitude toward the business, because consumers consider these initiatives as appropriate (Aaker, 1990; Aaker & Keller, 1993; Dean, 1999, 2002; Gross & Wiedmann, 2015; Speed & Thompson, 2000). In this context, Dean (1999) argued that the lack of congruence requires a reinterpretation of communication to create a connection with the consumer. This situation, in turn, hinders the consumer allocation process and leads to the formation of dubious beliefs about the interest of the company in the business development. Furthermore, Simmons and Becker-Olsen (2006) showed similar findings and demonstrated the negative effects of low congruence. Pointing to the same direction, Rodgers (2013) states that much of the empirical studies on sponsorship assume that partnerships between business and cause are more effective when they elicit congruence than when associations are incongruent. Based also on the Associative Networks theory, Lee, Lockshin, and Greenacre (2016) have recently demonstrated that product beliefs can influence country image but only when the product and country are congruent.

In the same vein, and taking into account Congruity Theory (Osgood & Tannenbaum, 1955), people remember and prefer harmony and continuity in their thoughts and thus strive to avoid conflicting thoughts, i.e. we, naturally, appreciate consistency between what we know and new information. The principle of congruity has recently proved valid in different business and marketing contexts such as international business cooperation (Buckley, Cross, & De Mattos, 2015), customer referral programs (Stumpf & Baum, 2016) and advertising (Kwon, Saluja, & Adaval, 2015; Zhang & Mao, 2016). In the field of CSR, Lucke and Heinze (2015) found that consumers evaluate associations and try to assimilate the differences between their thoughts and objects and give more credibility to social initiatives of companies that show congruence. In the same vein, Singhapakdi, Lee, Sirgy, and Senasu (2015) showed that incongruence between employee's and firm's CSR orientation is negatively associated with both lower- and higher-order need for satisfaction. Moreover, Cha, Yi, and Bagozzi (2016) examined the effects of corporate social responsibility-brand fit (CSR-brand fit) on service brand loyalty and found that CSR-brand fit strengthens both personal and social brand identification, which in turn increase consumers’ service brand loyalty. And recently, Rim, Yang, and Lee (2016) showed that congruence between a company and a nonprofit organization that cooperate in CSR initiatives lead to more positive WOM. Similarly, some authors suggest that the perceived congruity between the organization and the CSR initiative leads to facilitating effects in the association of two objects (Rifon, Choi, Trimble, & Li, 2004). Consistently, Till and Nowak (2000) posit that partnerships between a company and a cause are easier to relate when perceived compatibility between business activity and social responsibility campaign is high. Additionally, Gupta and Pirsch (2006) state that a high level of congruence between the company and the cause should materialize in a positive evaluation of products, leading to an eventual increase in purchase intention. Roy (2010) claims that despite the skepticism of some consumers regarding CSR (Ellen et al., 2000; Forehand & Grier, 2003), empirical results supporting that congruence exerts a greater favorable impact on consumer response than incongruent initiatives are more numerous.

Thus, based on strong evidence supporting the positive effect of congruence, it is reasonable to expect that high levels of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business will lead to more favorable consumer responses, as consumers infer reasons of continuity in the business perspective, ruling out the possibility of selfish behavior. If consumers interpret that congruence is determined by the social motivation of the company, they will not infer selfish motives. Therefore, when there is a high degree of congruence between the expectations, knowledge, associations, actions and responsibilities with respect to the activity of the company and the scope of CSR, the message will be integrated more easily into the cognitive structure of the consumer, strengthening the connection between business and CSR.

The positive effect of congruence should become apparent in terms of both responses to the CSR campaign itself as well as responses to the company. Therefore, we propose that congruence should lead to more positive CSR associations, more favorable attitude toward the CSR campaign, as well as higher willingness to purchase and recommend the product. Formally, we propose:H1

Congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business will positively affect consumer's CSR associations related to the company.

H2Congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business will positively affect consumer's attitude toward the CSR campaign.

H3Congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business will positively affect consumer's purchase intention.

H4Congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business will positively affect consumer's intention to recommend the product.

Consumer skepticism to CSRConsumer skepticism has been conceptualized as a signal that predisposes individuals to doubt about the veracity of certain forms of marketing communication such as advertising and public relations, and create a negative attitude toward the motives of the company (Obermiller & Spangenberg, 1998). When receiving information consumers opt to objective, accurate and easy to make sure information, instead of subjective information (Ford, Smith, & Swasy, 1990). Skepticism can emerge as a consumer response to companies’ actions and “refers to a person's tendency to doubt, disbelieve and question” (Skarmeas & Leonidou, 2013). Research on the scope of social responsibility suggests that skepticism related to CSR initiatives may appear when consumers attribute a selfish motivation to the company, that is, when they infer that it does not act voluntarily but instead it is looking for extra benefit. Skepticism may also arise when the CSR activities are difficult to verify by the consumer (Campbell & Kirmani, 2000; Forehand & Grier, 2003). However, the level of consumer skepticism varies from one consumer to another and these differences influence the effect of the CSR initiative on consumer behavior. Skepticism will be influenced by consumers’ prior knowledge about companies’ persuasive attempts (Friestad & Wright, 1994). A specific characteristic of skeptical people is that they can vary their thoughts when presented with a verified proof. Thus, the greater the value companies can communicate across their CSR action, the more favorable the consumers’ opinion will be (Skarmeas & Leonidou, 2013).

When a company makes promotional campaigns on CSR, if the prevailing message is social and communication is directly related to non-economic interests, source credibility improves (Priester & Petty, 1995). In this sense, and according to the Cognitive Theory, when a message is credible, attitude and consumer responses are more favorable (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Involvement may also play a role in relation to the conditions under which consumers infer attempts of persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). That is, in low involvement conditions, the use of signals of credibility will be more likely, as they require less processing information and facilitate the evaluation of arguments. However, they can also reduce consumers’ motivation to make complex inferences about the incentives of the company. When consumers are more skeptical, their involvement is higher and all issues concerning CSR initiatives are questioned and scrutinized with more elaboration. When expectations are not met, more time is spent thinking about the reasons why the firm carried out these initiatives, which will lead to more negative attributions (Marín, Cuestas, & Román, 2015). Therefore, when consumers distrust CSR initiatives and attribute a selfish motivation to the company (Campbell & Kirmani, 2000; Forehand & Grier, 2003; Webb & Mohr, 1998) will respond less favorably to the CSR campaign in a congruent scenario between the social responsibility initiative and the company's core business.

On the other hand, literature states that consumers experience some perplexity when confronted with incongruity, considering the shares of companies most appropriate and legitimate for their interest when the business setting is congruent with the CSR activities (Lee & Jeong, 2014). Congruity between the core business of the company and the CSR initiative triggers consumer learning through persuasive information processing and increases the familiarity and reputation of the company with the social initiative, which should reduce skepticism, driving to a transference of associations between the cause and the company, which turns into better attitude toward the CSR campaign (Dean, 1999) and more favorable CSR associations (Menon & Kahn, 2003). This leads us to propose that less skeptical consumers will have more favorable attitude toward the campaign and generate more CSR associations when business activity is congruent with the corporate social responsibility campaign, while more skeptical individuals will show less favorable responses. Formally:H5

Skepticism moderates the influence of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business on CSR associations. The effect of congruence will be stronger for less skeptical consumers compared to more skeptical ones.

H6Skepticism moderates the influence of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business on attitude toward the CSR campaign. The effect of congruence will be stronger for less skeptical consumers compared to more skeptical ones.

MethodologyProcedureWe used an experimental design through an online questionnaire, manipulating the level of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business (high vs. low) between subjects. A convenience sample of 120 subjects participated in the two scenarios, contacted through an invitation email sent to undergraduate students, enrolled in different degree programs of a medium sized university in Spain. 62 of them were assigned to the congruent scenario. 87 of the participants were women (72.5%), and age ranged from 18 to 69 years, with an average age of 26.54 years.

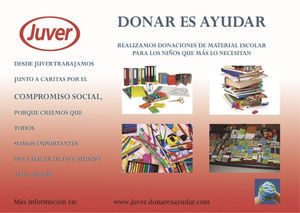

After introducing the study on the first page, participants were exposed to one of the two CSR campaigns. In the high congruence condition, the company engaged in a campaign related to a donation of food products the company manufactures to children through a charitable organization. In the low congruence condition, the context was the same but the products were school supplies. Then, subjects were asked to describe the campaign, to assure that the content had been fully understood. This was followed by questions related to their intention to recommend and purchase the products of the company, CSR associations, attitude toward the CSR campaign, and their skepticism toward CSR campaign.

We also introduced three control variables to rule out alternative explanations when testing our hypotheses: attitude toward the company, consumers’ perceived motivation about the firm's reasons to implement a CSR campaign, and the subject's perception of their own civic behavior. Our decision to consider these variables is based on the following arguments. First, as demonstrated by Becker-Olsen et al. (2006), perceived motivation can influence consumers’ thoughts about companies and their products. Civic behavior has been found to influence consumers trust toward the company or its products (van Ingen & Bekkers, 2015; Weber, Weber, Sleeper, & Schneider, 2004). Attitude toward the company has been found to influence purchase intention in different contexts (Cho, 2014) and the firm (a company operating in the food sector) was real and known in the area where the investigation was conducted. Finally, we checked the manipulation through a question about to what extent the CSR campaign was related to the company's core business.

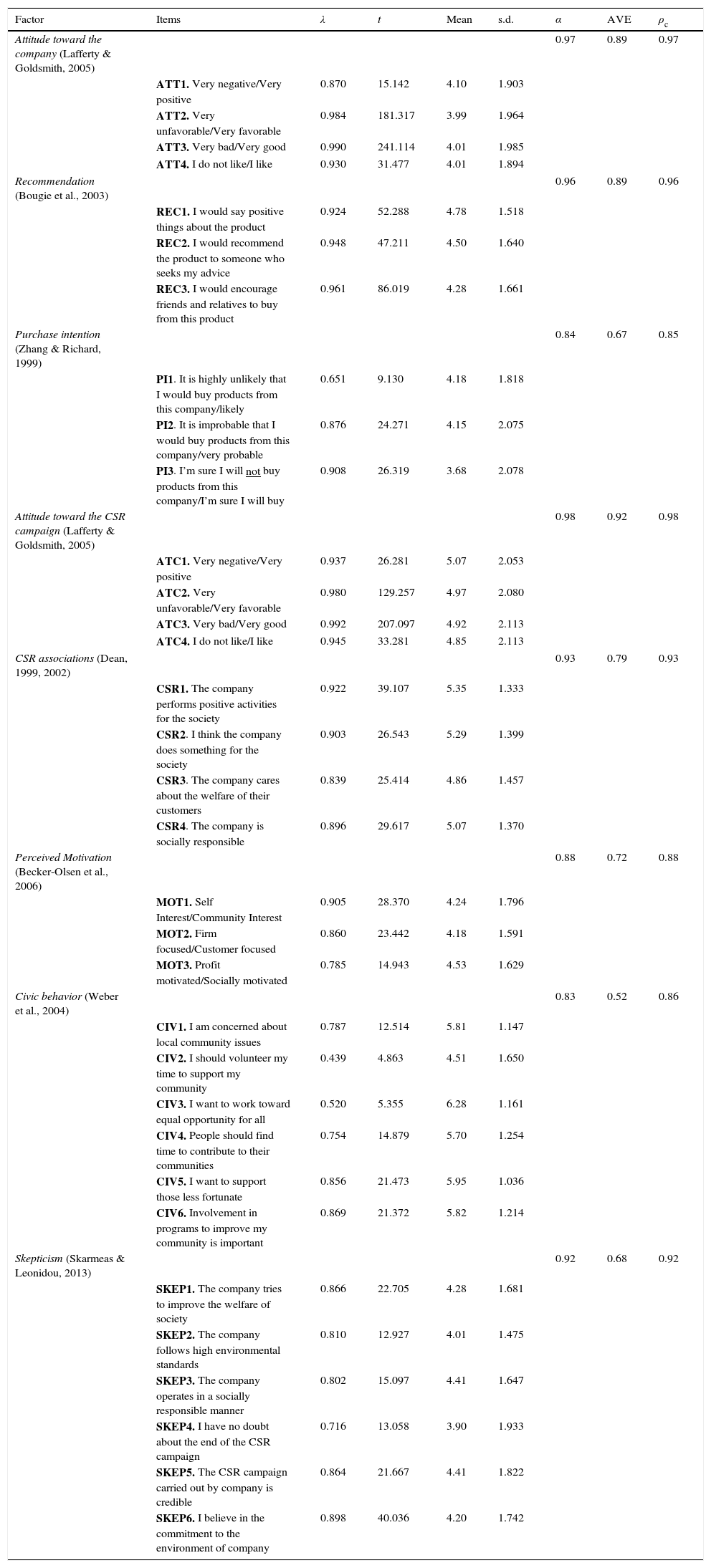

MeasurementWe used scales from previous literature to measure the main constructs (see Table 1), and when necessary adapted them to the purpose of the study. A first group included four scales scored from 1 to7 where 1 meant strongly disagree and 7 meant strongly agree: CSR associations with four items (Dean, 1999, 2002), recommendation with three items (Bougie, Pieters, & Zeelenberg, 2003), and civic behavior (Weber et al., 2004) and skepticism (Skarmeas & Leonidou, 2013) with six items each. In a second group of scales we included four semantic differential scales also measured through seven points: attitude toward the company and attitude toward the campaign (Lafferty & Goldsmith, 2005) were measured with four items each, purchase intention with three items (Zhang & Richard, 1999) and perceived motivation with three items too (Becker-Olsen et al., 2006).

Constructs and measures.

| Factor | Items | λ | t | Mean | s.d. | α | AVE | ρc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude toward the company (Lafferty & Goldsmith, 2005) | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.97 | |||||

| ATT1. Very negative/Very positive | 0.870 | 15.142 | 4.10 | 1.903 | ||||

| ATT2. Very unfavorable/Very favorable | 0.984 | 181.317 | 3.99 | 1.964 | ||||

| ATT3. Very bad/Very good | 0.990 | 241.114 | 4.01 | 1.985 | ||||

| ATT4. I do not like/I like | 0.930 | 31.477 | 4.01 | 1.894 | ||||

| Recommendation (Bougie et al., 2003) | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.96 | |||||

| REC1. I would say positive things about the product | 0.924 | 52.288 | 4.78 | 1.518 | ||||

| REC2. I would recommend the product to someone who seeks my advice | 0.948 | 47.211 | 4.50 | 1.640 | ||||

| REC3. I would encourage friends and relatives to buy from this product | 0.961 | 86.019 | 4.28 | 1.661 | ||||

| Purchase intention (Zhang & Richard, 1999) | 0.84 | 0.67 | 0.85 | |||||

| PI1. It is highly unlikely that I would buy products from this company/likely | 0.651 | 9.130 | 4.18 | 1.818 | ||||

| PI2. It is improbable that I would buy products from this company/very probable | 0.876 | 24.271 | 4.15 | 2.075 | ||||

| PI3. I’m sure I will not buy products from this company/I’m sure I will buy | 0.908 | 26.319 | 3.68 | 2.078 | ||||

| Attitude toward the CSR campaign (Lafferty & Goldsmith, 2005) | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.98 | |||||

| ATC1. Very negative/Very positive | 0.937 | 26.281 | 5.07 | 2.053 | ||||

| ATC2. Very unfavorable/Very favorable | 0.980 | 129.257 | 4.97 | 2.080 | ||||

| ATC3. Very bad/Very good | 0.992 | 207.097 | 4.92 | 2.113 | ||||

| ATC4. I do not like/I like | 0.945 | 33.281 | 4.85 | 2.113 | ||||

| CSR associations (Dean, 1999, 2002) | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.93 | |||||

| CSR1. The company performs positive activities for the society | 0.922 | 39.107 | 5.35 | 1.333 | ||||

| CSR2. I think the company does something for the society | 0.903 | 26.543 | 5.29 | 1.399 | ||||

| CSR3. The company cares about the welfare of their customers | 0.839 | 25.414 | 4.86 | 1.457 | ||||

| CSR4. The company is socially responsible | 0.896 | 29.617 | 5.07 | 1.370 | ||||

| Perceived Motivation (Becker-Olsen et al., 2006) | 0.88 | 0.72 | 0.88 | |||||

| MOT1. Self Interest/Community Interest | 0.905 | 28.370 | 4.24 | 1.796 | ||||

| MOT2. Firm focused/Customer focused | 0.860 | 23.442 | 4.18 | 1.591 | ||||

| MOT3. Profit motivated/Socially motivated | 0.785 | 14.943 | 4.53 | 1.629 | ||||

| Civic behavior (Weber et al., 2004) | 0.83 | 0.52 | 0.86 | |||||

| CIV1. I am concerned about local community issues | 0.787 | 12.514 | 5.81 | 1.147 | ||||

| CIV2. I should volunteer my time to support my community | 0.439 | 4.863 | 4.51 | 1.650 | ||||

| CIV3. I want to work toward equal opportunity for all | 0.520 | 5.355 | 6.28 | 1.161 | ||||

| CIV4. People should find time to contribute to their communities | 0.754 | 14.879 | 5.70 | 1.254 | ||||

| CIV5. I want to support those less fortunate | 0.856 | 21.473 | 5.95 | 1.036 | ||||

| CIV6. Involvement in programs to improve my community is important | 0.869 | 21.372 | 5.82 | 1.214 | ||||

| Skepticism (Skarmeas & Leonidou, 2013) | 0.92 | 0.68 | 0.92 | |||||

| SKEP1. The company tries to improve the welfare of society | 0.866 | 22.705 | 4.28 | 1.681 | ||||

| SKEP2. The company follows high environmental standards | 0.810 | 12.927 | 4.01 | 1.475 | ||||

| SKEP3. The company operates in a socially responsible manner | 0.802 | 15.097 | 4.41 | 1.647 | ||||

| SKEP4. I have no doubt about the end of the CSR campaign | 0.716 | 13.058 | 3.90 | 1.933 | ||||

| SKEP5. The CSR campaign carried out by company is credible | 0.864 | 21.667 | 4.41 | 1.822 | ||||

| SKEP6. I believe in the commitment to the environment of company | 0.898 | 40.036 | 4.20 | 1.742 |

We first checked the reliability, validity, and unidimensionality of the measurement scales used in the study (Table 1). The reliability of the constructs was initially assessed through Cronbach's alpha coefficients, which were above 0.7 for all constructs.

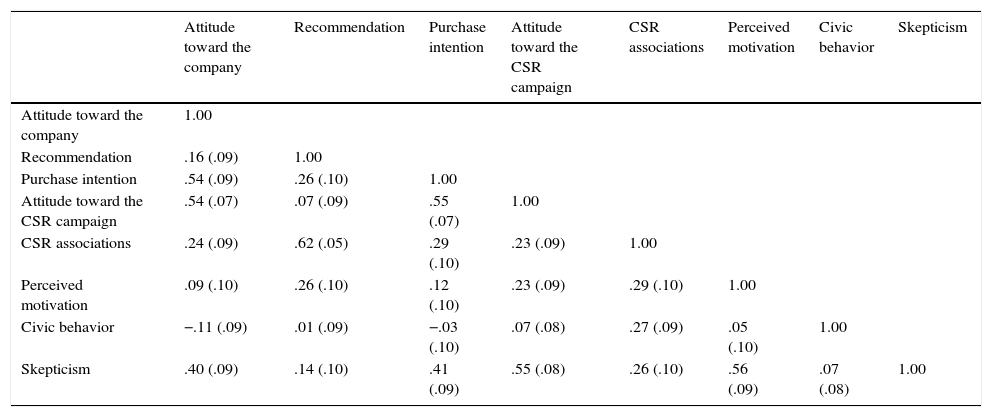

Results of a confirmatory factor analysis showed that the proposed measurement model fits the data well. Preliminary analyses indicated some skewed measures, suggesting non-normal data. We therefore used the asymptotic covariance matrix as input and robust maximum likelihood as the method of estimation (Satorra & Bentler, 2001). The goodness-of-fit statistics for the model were as follows: (χS-B2 (467)=697.19, p≈0.00; RMSEA=0.064; SRMR=0.068; NNFI=0.93; CFI=0.94). We also evaluated internal consistency of constructs using two measures: the composite reliability (ρc) and the average variance extracted (AVE). For all constructs, both measures were higher than the evaluation criteria of 0.60 and 0.50, respectively (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988), as Table 1 shows. Moreover, based on Fornell and Larcker's (1981) suggested procedure, the scales showed acceptable convergent and discriminant validity. The former, convergent validity, was met because all indicators had statistically significant loadings on their respective latent constructs. Discriminant validity, first, because the phi matrix and associated robust standard errors shown in Table 2 ensured that unit correlation among latent variables was extremely unlikely (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988) and, second, because for all the pairwise relationships in the phi matrix, the AVE for each latent variable exceeded the square of the correlation between the variables.

Phi matrix of latent construct.

| Attitude toward the company | Recommendation | Purchase intention | Attitude toward the CSR campaign | CSR associations | Perceived motivation | Civic behavior | Skepticism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude toward the company | 1.00 | |||||||

| Recommendation | .16 (.09) | 1.00 | ||||||

| Purchase intention | .54 (.09) | .26 (.10) | 1.00 | |||||

| Attitude toward the CSR campaign | .54 (.07) | .07 (.09) | .55 (.07) | 1.00 | ||||

| CSR associations | .24 (.09) | .62 (.05) | .29 (.10) | .23 (.09) | 1.00 | |||

| Perceived motivation | .09 (.10) | .26 (.10) | .12 (.10) | .23 (.09) | .29 (.10) | 1.00 | ||

| Civic behavior | −.11 (.09) | .01 (.09) | −.03 (.10) | .07 (.08) | .27 (.09) | .05 (.10) | 1.00 | |

| Skepticism | .40 (.09) | .14 (.10) | .41 (.09) | .55 (.08) | .26 (.10) | .56 (.09) | .07 (.08) | 1.00 |

To provide a further check of discriminant validity, for each pair of the latent variables, we compared the chi-square statistic of the hypothesized measurement model with that of a second model that constrained the correlation between those latent variables to unity. The S–B chi-square difference tests indicated that the hypothesized measurement model was always superior to the constrained model. In summary, internal consistency and discriminant validity results enabled us to proceed with the estimation of the model.

ResultsBefore testing the hypotheses, we checked the manipulation of the level of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business. Thus, the participants reported their level of agreement with three statements (e.g., “the CSR campaign and the company are very consistent”) scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). We took the average of the three items as the score to check the manipulation. As expected, those individuals exposed to the high congruence condition scored higher in that item than those exposed to the low congruence condition (MHC=4.75; MLC=4.28; F(1,118)=4.38; p<.05).

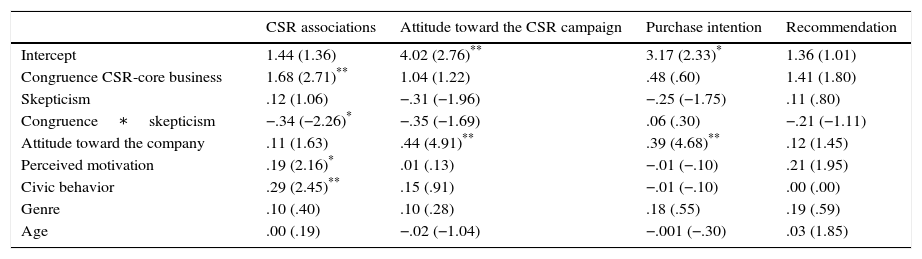

In order to test the hypotheses concerning the effect of congruence on behavioral variables and the moderation effect of skepticism, we ran four regression analyses (Table 3). As independent variables related to the hypotheses, we entered congruence of the CSR campaign, the subject's skepticism and their interaction. In addition, we entered five control variables: gender, age, attitude toward the company, perceived motivation or the firm's reasons to implement a CSR campaign and subject's perception of own civic behavior.

Regression models betas (t values).

| CSR associations | Attitude toward the CSR campaign | Purchase intention | Recommendation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.44 (1.36) | 4.02 (2.76)** | 3.17 (2.33)* | 1.36 (1.01) |

| Congruence CSR-core business | 1.68 (2.71)** | 1.04 (1.22) | .48 (.60) | 1.41 (1.80) |

| Skepticism | .12 (1.06) | −.31 (−1.96) | −.25 (−1.75) | .11 (.80) |

| Congruence∗skepticism | −.34 (−2.26)* | −.35 (−1.69) | .06 (.30) | −.21 (−1.11) |

| Attitude toward the company | .11 (1.63) | .44 (4.91)** | .39 (4.68)** | .12 (1.45) |

| Perceived motivation | .19 (2.16)* | .01 (.13) | −.01 (−.10) | .21 (1.95) |

| Civic behavior | .29 (2.45)** | .15 (.91) | −.01 (−.10) | .00 (.00) |

| Genre | .10 (.40) | .10 (.28) | .18 (.55) | .19 (.59) |

| Age | .00 (.19) | −.02 (−1.04) | −.001 (−.30) | .03 (1.85) |

Results show that three control variables have significant effects on the dependent variables. Attitude toward the company positively influences attitude toward the CSR campaign (β=.45, t (113)=5.17, p<.00) and purchase intention (β=.40, t (113)=4.85, p<.00). Perceived motivation of the company significantly influences the other two dependent variables: CSR associations (β=.19, t (113)=2.32, p<.02) and the person intention to recommend the products manufactured by the company (β=.26, t (113)=2.47, p<.02). Civic behavior only influences CSR associations, showing that the higher the subject's civic behavior, the higher his/her CSR associations (β=.31, t (113)=2.66, p<.02). Gender and age were not significant in any of the regressions and, as such, were removed them for the subsequent analyses.

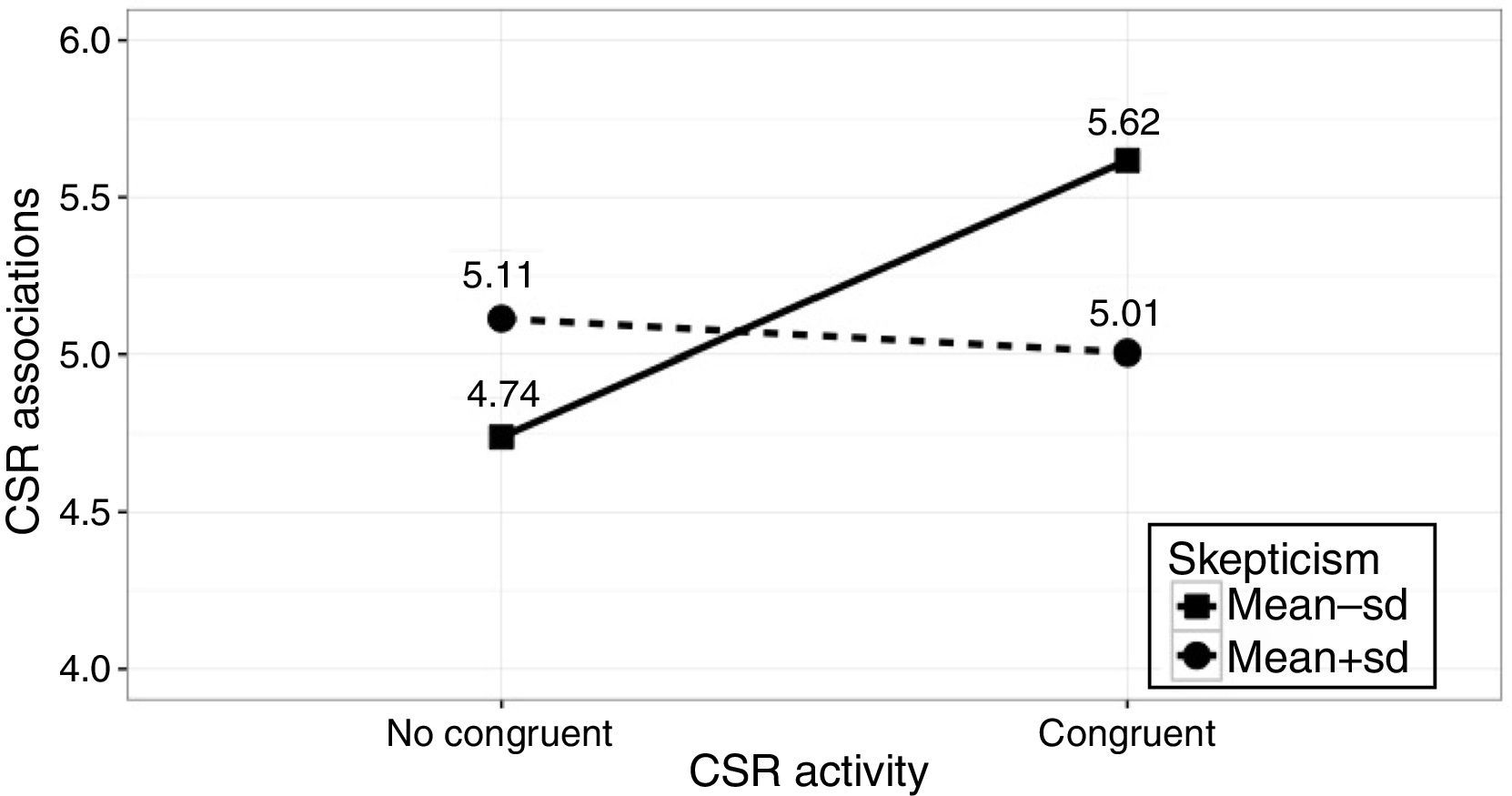

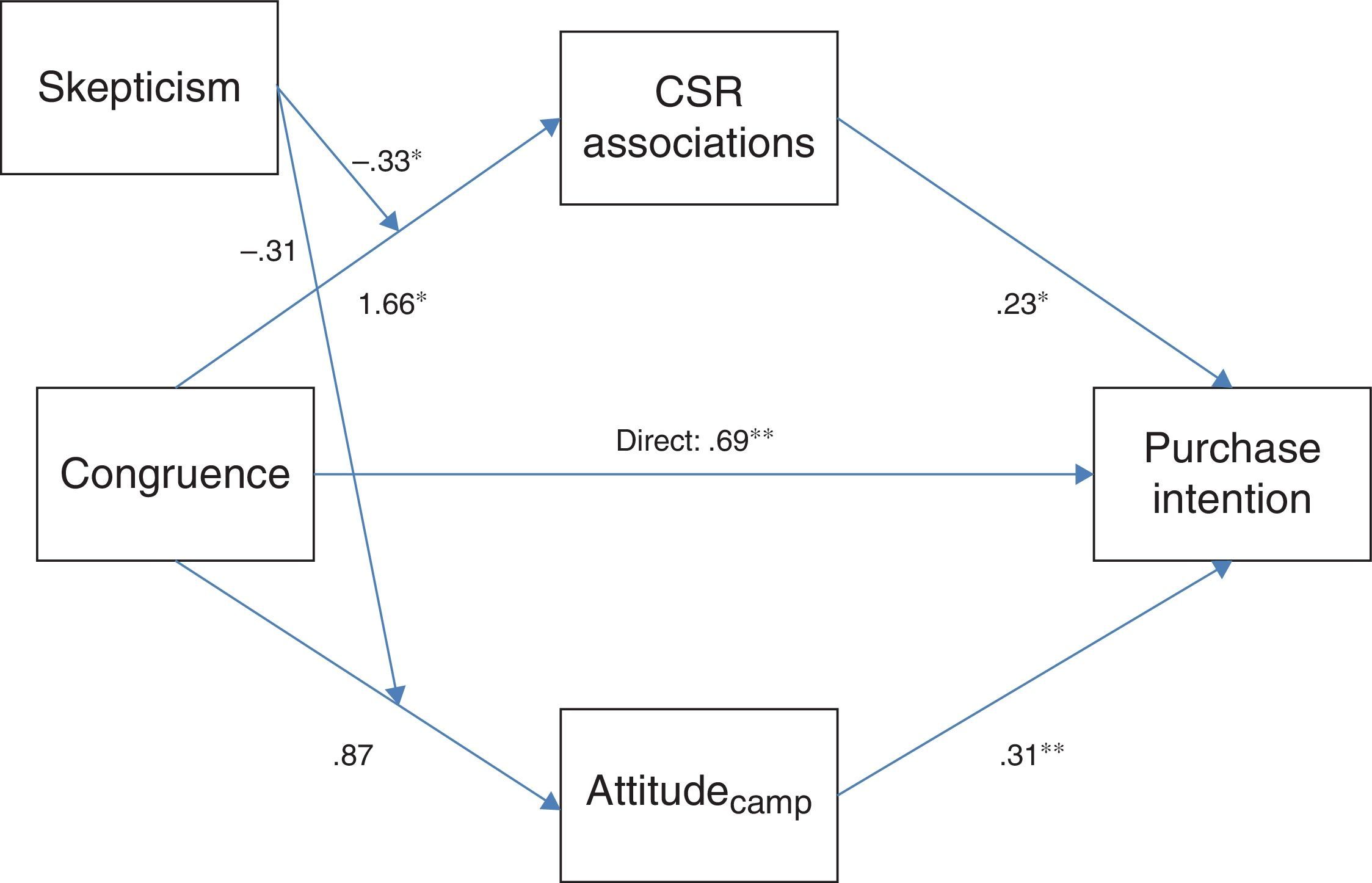

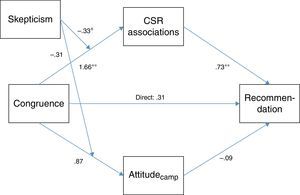

Hypotheses H1 and H4 are confirmed by the results. Congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business positively affects CSR associations related to the company (β=1.66, t (113)=2.76, p<.01), as well as the consumer's intention to recommend the products manufactured by the company (β=1.56, t (113)=2.02, p<.05). However, this perception of congruence does not influence the attitudes toward the CSR campaign (β=.87, t (113)=1.05, p<.30) and the purchase intention of the products that represent the core business of the firm (β=.38, t (113)=0.49, p<.63). Therefore, neither H2 nor H3 are confirmed.

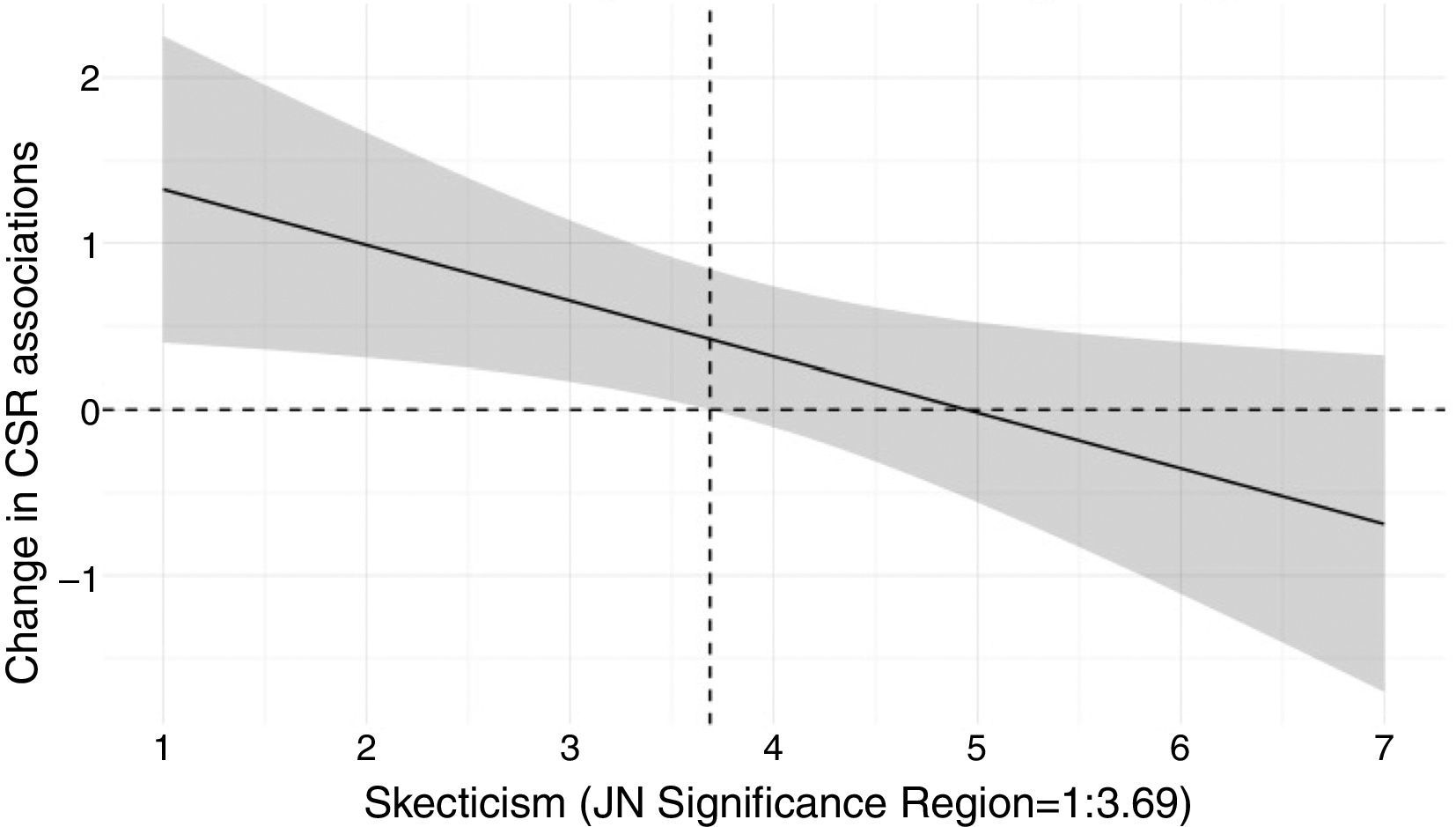

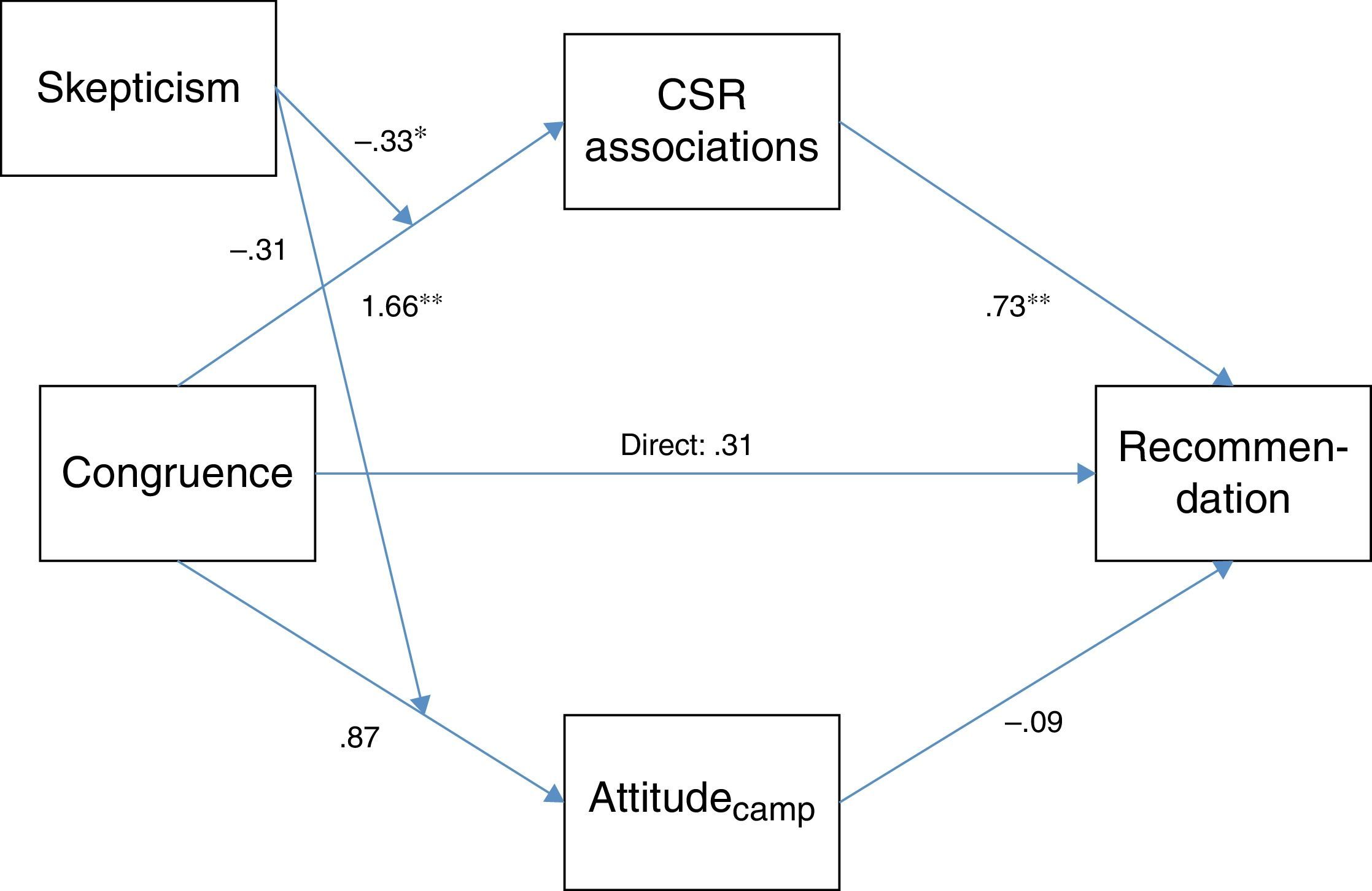

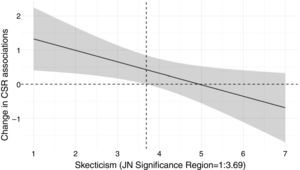

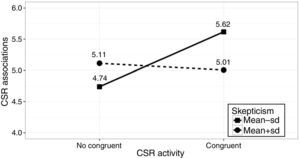

More interesting, we find a significant interaction effect of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business and skepticism that influences the subject's CSR associations (β=−.34, t (113)=−2.29, p<.03). This result confirms H5. We then conduct a floodlight analysis through the Johnson–Neyman (J–N) approach (Spiller, Fitzsimons, Lynch, & McClelland, 2013) to identify the regions on the skepticism scale where the effect of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business is significant. Results (Fig. 1) show that for any skepticism score lower than 3.69, the effect of congruence is significant: subjects show more CSR associations as CSR campaign changes from low to high level of congruence when their skepticism is low (β=.88, t (113)=2.87, p<.01, for skepticism=2.33, i.e., mean−1 standard deviation), as shown in Fig. 2. However, when the consumer skepticism is medium or high (above 3.69), congruence does not have an effect on subjects’ CSR associations (β=−.11, t (113)=−.36, p<.72, for skepticism=5.27, i.e., mean+1 standard deviation). H6 is, therefore, not confirmed (β=−.31, t (113)=−1.56, p<.13).

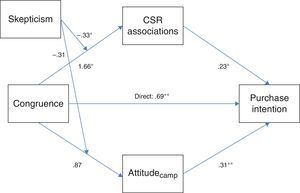

Furthermore, using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2013), we conducted two mediated moderation analyses (for purchase intention and for recommendation) with congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business as the independent variable, consumer skepticism as moderator and CSR associations and attitude toward the campaign as mediators. These two mediators do not show any significant relationship when introduced one of them as mediator for the other and vice versa. We also maintained the three control variables in the analyses both for the mediators and the dependent variables: attitude toward the company, perceived motivation or the firm's reasons to implement a CSR campaign and subject's perception of own civic behavior.

Results are summarized in Figs. 3 and 4. For purchase intention, we can see that the effect of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business on purchase intention is partially mediated through the subject's CSR associations. While the direct effect of congruence is significant (β=.69, t (113)=2.68, p<.01), the indirect effect is significant when skepticism is low (β=.20, bootstrap confidence interval=(.03, .50), for skepticism=2.33, i.e., mean−1 standard deviation). This effect is not significant when skepticism is around the mean value or high (β=−.02, bootstrap confidence interval=(−.28, .16), for skepticism=5.27, i.e., mean+1 standard deviation). On the other hand, for the variable recommendation of the products manufactured by the company, results indicate a full mediation effect of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business through the subject's CSR associations. The direct effect is not significant (β=.31, t (113)=1.39, p<.17), but the indirect effect is, although again only for subjects with low skepticism (β=.65, bootstrap confidence interval=(.30, 1.13), for skepticism=2.33, i.e., mean−1 standard deviation), while it is not significant when skepticism is around the mean value or higher (β=−.08, bootstrap confidence interval=(−.69, .49), for skepticism=5.27, i.e., mean+1 standard deviation).

DiscussionPrevious literature has dealt with the effect of congruence on consumers’ responses. A negative influence has been proposed and tested in the specific field of cause-related marketing while a positive influence has been suggested in the context of CSR. In this paper, we aim to further analyze the role of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business and propose that a moderating variable, skepticism, needs to be taken into account to fully understand how congruence affects CSR campaign-related output (CSR associations and attitude toward the campaign) and product-related output (purchase intention and recommendation).

In line with Osgood and Tannenbaum's (1955) Congruity Theory, our results confirm that congruence positively contribute to CSR, purchase intention and recommendation. However, it does not place an effect on attitude toward the campaign, which is consistent with the non-significant relationship between brand/cause fit and attitude toward the ad found by Nan and Heo (2007). Furthermore, our findings provide a deeper understanding of congruence, as we introduce skepticism. Thus, as consumer process information, congruence only has a significant role when consumers show low levels of skepticism toward that CSR activity. On the contrary, when consumers are moderately to highly skeptical, congruence does not lead to higher CSR associations. In addition, the effect of congruence between the CSR campaign and the company's core business on purchase intention and recommendation is partially and fully, respectively, mediated through the subject's CSR associations. Importantly, these effects only show up when consumers are not skeptical about the company's CSR activity. This result is in line with previous studies suggesting that skepticism can explain, at least partially, why consumers behave the way they do when exposed to CSR initiatives (Skarmeas & Leonidou, 2013).

To summarize, we have contributed to literature on CSR by clarifying the effect of congruence on consumers’ responses and by demonstrating that the positive influence only occurs for less skeptical consumers. Furthermore, CSR associations have proved to be a mediating mechanism through which congruence impact product-related variables.

The managerial implications to be drawn from this work are straightforward. Maintaining some links between the core business and the CSR activity will lead consumers to elicit more positive thoughts about the company and its products, through the connection of business and CSR causes. In other words, linking what the company regularly does and is well known for (its products) and other socially responsible actions will favor the image of the company as well as its reputation. That, in turn, will be transferred to the image of the brand/products and will result in greater willingness to buy them.

Furthermore, marketers should pay special attention to reducing consumers’ skepticism toward CSR. Even if the campaign is well designed and implemented in terms of congruence with the firm's core business, consumers favorable responses will depend on whether they believe in the CSR claims or not. Communication efforts should be made to convince them that the company's motives are honest and socially driven. Those efforts should not be only linked to the CSR campaign at hand but also to the overall transparency and openness policy.

Although the authors of this study feel that the results presented here definitely have merit, they are not without limitations. To begin with, the sample size was relatively small. Moreover, the analysis focuses on the food sector so we cannot generalize the findings to other industries.

The limitations mentioned in the previous paragraph offer avenues for future research. We could replicate our study with a bigger sample in other context to test whether they are robust across different situations. Furthermore, new explanatory variables could be added to identify and better comprehend the impact of congruence on the dependent variables. Both context-related (involvement with the specific cause) or personality traits (e.g. social orientation) variables could also play a key role. Similarly, it would be interesting to consider the effect of sociodemographic and cultural variables.

ConclusionsWith this research we have demonstrated the positive effect of congruence between the CSR action and the company's core business on CSR associations, purchase intention and recommendation. We have also identified skepticism as a moderator in the relationships we tested. Specifically, the favorable influence of congruence only emerges under low levels of skepticism whereas it vanishes for moderate to high levels of skepticism.

FundingThe author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the grant ECO2012-35766 from the Spanish Ministry of Economics and Competitiveness. Authors also thank the support provided by Fundación Cajamurcia.

Conflict of interestNone.