Treatment resistant depression (TRD) is one of the most pressing issues in mental healthcare in LatAm. However, clinical data and outcomes of standard of care (SOC) are scarce. The present study reported on the Treatment-Resistant Depression in America Latina (TRAL) project 1-year follow-up of patients under SOC assessing clinical presentation and outcomes.

Materials and methods420 patients with clinical diagnoses of TRD from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico were included in a 1-year follow-up to assess clinical outcomes of depression (MADRS) and suicidality (C-SSRS), as well as evolution of clinical symptoms of depression. Patients were assessed every 3 months and longitudinal comparison was performed based on change from baseline to each visit and end of study (12 months). Socio demographic characterization was also performed.

ResultsMost patients were female (80.9%), married (42.5%) or single (34.4%), with at least 10 years of formal education (71%). MDD diagnosis was set at 37.29 (SD=14.00) years, and MDD duration was 11.11 years (SD=10.34). After 1-year of SOC, 79.1% of the patients were still symptomatic, and 40% of the patients displayed moderate/severe depression. Only 44.1% of the patients achieved a response (≥50% improvement in MADRS), and 60% of the sample failed to achieve remission. Suicidal ideation was reported by more than half of the patients at the end of study.

ConclusionsDepression and suicidality symptoms after a 1-year of SOC is of great concern. Better therapeutic options are needed to tackle this debilitating and burdensome disease.

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is an affective disorder and one of the most severe forms of depression, affecting around 6% of the world's population and significantly contributing to worldwide disability.1–3

MDD patients frequently fail to recover under current Standard-of-care (SOC),4 often leading to the development of Treatment-Resistant Depression (TRD). TRD has been reported in over one-third of MDD patients.5–7 This more severe form of MDD is usually defined as a failure to respond to two or more antidepressants at therapeutic doses, over an appropriate period of time, within the current depressive episode,8 even though the definition is debatable.

TRD burden is higher than MDD, straining all stakeholders (from patients to healthcare decision makers). TRD patients display longer course of illness, higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicide-related occurrences, translating into higher economic, work productivity and healthcare burden of the disease, and a detrimental impact on quality of life,5,9–14 compared to MDD patients.13,15,16 A direct comparison of TRD and non-TRD patients from data in Spain further underlined the added economic burden of the condition,17 while the EPICO study presented the noticeable impact of depressive disorders in Spain.18 Moreover, the longer course of illness negatively impacts on the severity of suicide/suicide-related outcomes, the most burdensome symptom. TRD onset and age at first suicidal thought both act as predictors for suicidality.19,20

SOC includes a large spectrum of treatment options and depends on the severity of TRD. Antidepressants (AD) are the first-line of treatment, which can be switched after a short period of non-response (usually a minimum of 4 weeks). Other options include antipsychotics and combinations with other available treatments (such as psychotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy).21–25 Therapeutic choice is also influenced by disease stage (acute, continuation and maintenance), and can include combination, augmentation and potentiation strategies.26 Treatment remains a pressing issue and an unmet need in MDD/TRD, since the proportion of patients with clinical response to treatment is far from the desirable outcomes.9 This is evident regardless of the treatment guidelines followed,21–25,27 suggesting the need for more efficacious treatments.28,29 However, data on the outcomes of SOC provided for TRD in LatAm are scarce.

The TRAL (Treatment-Resistant Depression in America Latina) was a multinational study aiming primarily to estimate the prevalence of TRD among MDD patients routinely followed at public and private healthcare settings, in the study's phase 1. This characterization provided much needed insights and robust data on TRD clinical characterization, including psychiatric/clinically symptoms, as well burden of the disease. This paper reports on the phase 2 of the study, which included a 1-year follow-up of the prevalent pool of TRD patients identified in Phase 1 under SOC. The main objectives were to assess disease presentation and clinical outcomes.

Materials and methodsStudy design and populationTRAL was a multicenter, multinational, observational study conducted in a real-world setting (October 2017–December 2018) which included regional psychiatric sites from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. The TRAL study was designed with two distinct phases: Phase 1 (cross-sectional)30,31 focused on epidemiology of TRD, and a phase 2 follow-up of TRD patients. Phase 2 was focused on a 1-year follow-up of TRD patients under SOC, assessing clinical and safety outcomes (e.g. clinical depression and suicidal ideation) and changes in several dimensions (e.g. quality of life, disability). The present analysis refers to the analysis of clinical outcomes after 1-year follow-up of TRD patients under SOC in the LatAm. Regional centers were all reference psychiatric treatment sites, including general hospitals, public and private psychiatric hospitals (see supplemental Table 1). Centers were selected to ensure a correct representation of the context in 4 LatAm countries. From 430 TRD patients clinically diagnosed with TRD based on DSM-5 criteria, confirmed by MINI, and according to the study's TRD definition, a sample of 420 patients were included in phase 2 analysis. A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study has been previously published (Soares et al., 2021; Corral et al., 2022).

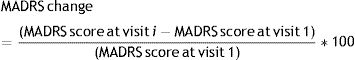

Data and assessmentsAssessments were based on validated measures and efforts were implemented to ensure that the person who collected the information was the same between baseline and follow-up. Montgomery – Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)32 is a 10-item scale used to assess depression severity, which shows a good discrimination between responders/non-responders to antidepressants, particularly to assess response to SOC over time. The following variables were calculated: (a) Change of MADRS score from visit 1 (%) – The following formula must be considered:

(b) Response – Yes – Patients with a reduction of ≥50% in the total MADRS score as compared to visit 1 score; (c) Remission – Yes – Patients with MADRS total score≤12; (d) Relapse – Yes – Patients with response in the previous visit but without response in the current visit.

TRD diagnosis was based on the following criteria: patients had to be followed up adequately and treated with ≥2 antidepressants in the current episode, with absence of response to treatment based on MADRS.8

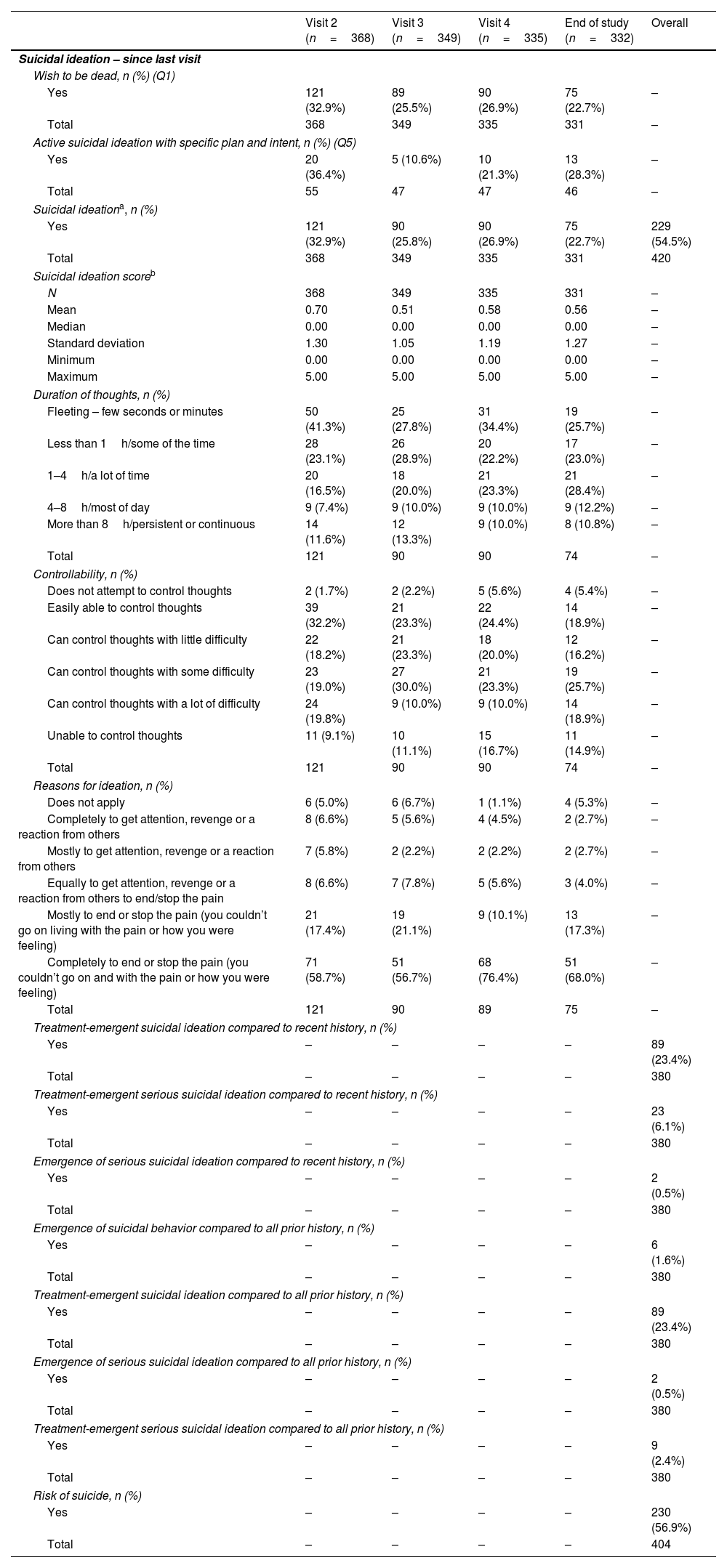

Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) is a 10-item scale that assesses suicide severity, having several versions to ensure lifetime characterization, current (last month) or since last previous assessment. The following measures were calculated: (a) Suicidal Ideation Score, (b) Suicidal ideation (dichotomous), (c) Suicidal behavior (dichotomous), (d) Suicidal ideation or behavior (dichotomous), (e) Treatment-emergent suicidal ideation compared to recent history, (f) Treatment-emergent serious suicidal ideation compared to recent history, (g) Emergence of serious suicidal ideation compared to recent history, (h) Improvement in suicidal ideation at a time point of interest compared to Visit 1, (i) Emergence of suicidal behavior compared to all prior history, (j) Treatment-emergent suicidal ideation compared to all prior history, (k) Emergence of serious suicidal ideation compared to all prior history, (l) Treatment-emergent serious suicidal ideation compared to all prior history, and (m) Risk of suicide. Scoring and other calculations can be found in Supplemental Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical features at baseline were collected and assessed by a physician, while clinical features were again collected at the end of the study.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by local Independent Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board.

Statistical analysisSample size was calculated in accordance with the percentage of patients that are resistant to the SOC and considering a type I error value of 5% (α=0.05), a type II error value of 20% (β=0.20), for a 21.7% prevalence with a 95% confidence and 80% power. 334 testable patients were required as sample size (387 patients’ recruitment considering a 15% surplus for possible sample losses).

The overall TRD sample in LatAm included 420 patients. A 1-year follow-up of 387 individuals with TRD – later increased to 420 based on the clinical diagnosis of treatment resistance – was performed, from a sample of 1544 MDD patients evenly distributed across countries, in accordance with ongoing assessments during the development of the project. When TRD patients quota was achieved, all remaining TRD patients were not included in the phase 2 sample.

Quantitative variables were summarized as mean, median, standard deviation minimum and maximum, and qualitative variables were summarized as absolute frequency and percentage, overall and by TRD and non-TRD subgroups. Longitudinal comparisons on clinical outcomes were performed with a Generalized estimating equation model for a 95% Confidence interval. Co-variables were not included in the model.

There was no imputation of missing data. Statistical significance was set at 5%. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS® (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary).

ResultsPatient disposition, sociodemographic characteristics and disease course at visit 1From an initial sample of 1475 MDD patients enrolled in 4 LatAm countries, 430 were diagnosed with TRD. Sociodemographic characterization was based in the initial set of 430 patients with TRD at visit 1 (baseline). Still, only 420 patients with TRD were included in the second phase (1-year follow-up) of the study due to: (1) quota for inclusion in the longitudinal phase already achieved [n=5], (2) non-compliance with the protocol [n=2], (3) phase 2 inclusion criteria not met [n=2], and (4) refusal to participate in phase 2 [n=1].

Over 75% (n=317) of the patients included in Phase 2 completed the 1-year follow-up. For the ones not completing the follow-up, 60 (58.3%) were losses to follow-up, 13 (12.6%) withdrew the consent, 3 (2.9%) died and 27 (26.2%) were lost due to unspecified reasons.

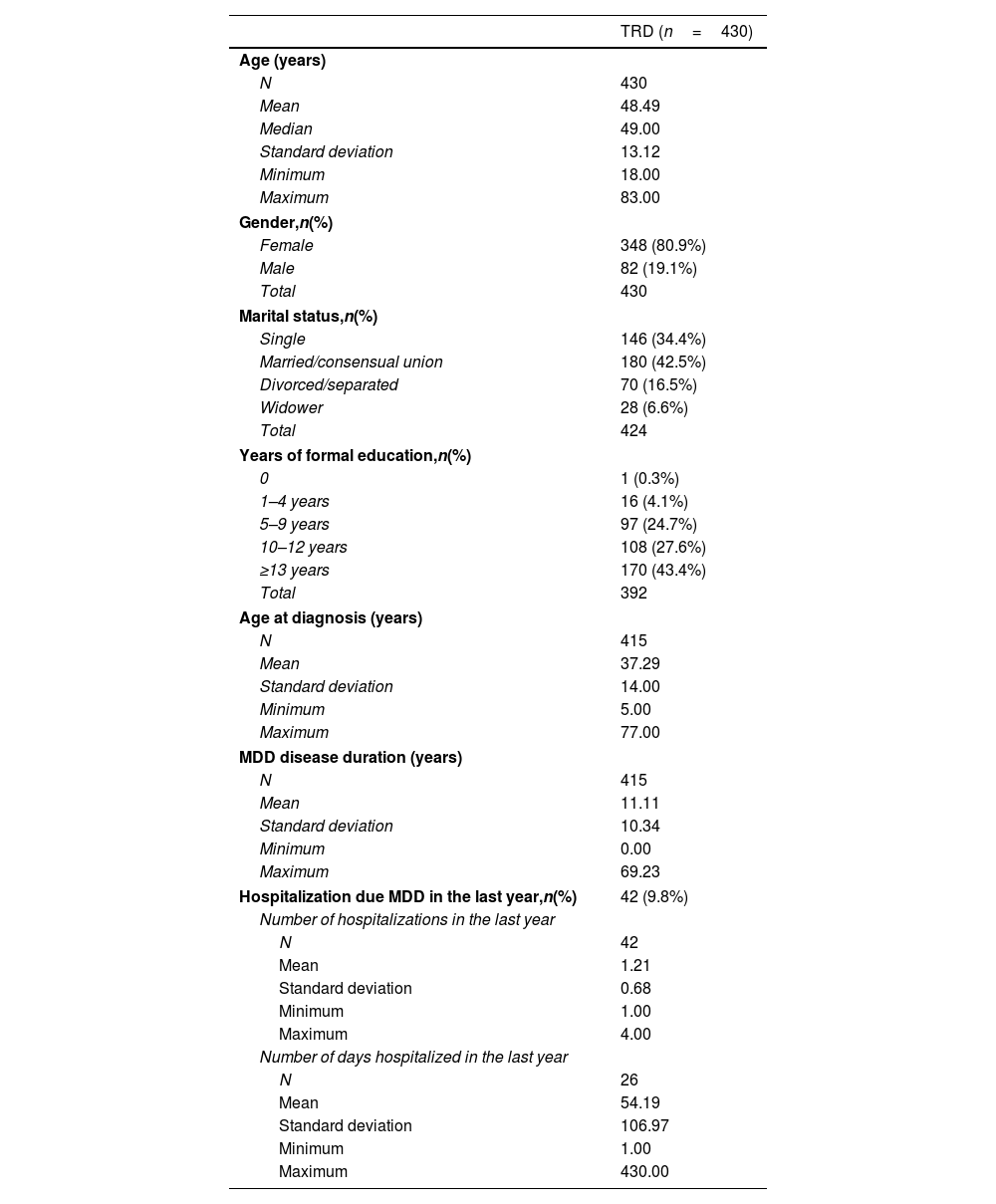

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic data at baseline. Mean age was approximately 48 years (± 13.12), with a higher proportion of female patients (80.9%). Concerning marital status, 42.5% of patients were married or in a consensual union and 34.4% were single. The majority (71%) of patients has at least 10 years of formal education.

Sociodemographic data and disease course at visit 1 (baseline).

| TRD (n=430) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| N | 430 |

| Mean | 48.49 |

| Median | 49.00 |

| Standard deviation | 13.12 |

| Minimum | 18.00 |

| Maximum | 83.00 |

| Gender,n(%) | |

| Female | 348 (80.9%) |

| Male | 82 (19.1%) |

| Total | 430 |

| Marital status,n(%) | |

| Single | 146 (34.4%) |

| Married/consensual union | 180 (42.5%) |

| Divorced/separated | 70 (16.5%) |

| Widower | 28 (6.6%) |

| Total | 424 |

| Years of formal education,n(%) | |

| 0 | 1 (0.3%) |

| 1–4 years | 16 (4.1%) |

| 5–9 years | 97 (24.7%) |

| 10–12 years | 108 (27.6%) |

| ≥13 years | 170 (43.4%) |

| Total | 392 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |

| N | 415 |

| Mean | 37.29 |

| Standard deviation | 14.00 |

| Minimum | 5.00 |

| Maximum | 77.00 |

| MDD disease duration (years) | |

| N | 415 |

| Mean | 11.11 |

| Standard deviation | 10.34 |

| Minimum | 0.00 |

| Maximum | 69.23 |

| Hospitalization due MDD in the last year,n(%) | 42 (9.8%) |

| Number of hospitalizations in the last year | |

| N | 42 |

| Mean | 1.21 |

| Standard deviation | 0.68 |

| Minimum | 1.00 |

| Maximum | 4.00 |

| Number of days hospitalized in the last year | |

| N | 26 |

| Mean | 54.19 |

| Standard deviation | 106.97 |

| Minimum | 1.00 |

| Maximum | 430.00 |

TRD, Treatment Resistant Depression.

Mean age at diagnosis was 37.3 (± 14.0) years and overall MDD duration was 11.1±10.3 years – Table 1. Nearly 10% of patients were hospitalized in the previous year due to MDD. The mean number of hospitalizations in the same period was 1.2 (± 0.7) with a mean duration of 54.0 (± 107) days.

Prior medical conditions and treatment at visit 1Almost two-thirds of the patients (63.5%) reported another disease besides MDD, with a higher. Cardiovascular and endocrinological diseases were the most frequent among TRD patients. The proportion of cardiovascular diseases was 50.9%, followed by endocrinological (48.0%), skeletal muscle diseases (27.8%) and digestive diseases (26.7%) (supplemental Table 3).

Concerning treatment at baseline, 97.0% of the patients had previous psychiatric medication and 10.5% had other previous relevant medication. At visit 1, 97.4% of the patients were on treatment with relevant psychiatric therapy and 48.1% with other relevant therapy.

Selective-Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI) was the most frequent class of antidepressants reported as current medication (57.9%), followed by Antipsychotics (41.6%) and Serotonin and Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRI) (40.5%) (supplemental Table 4).

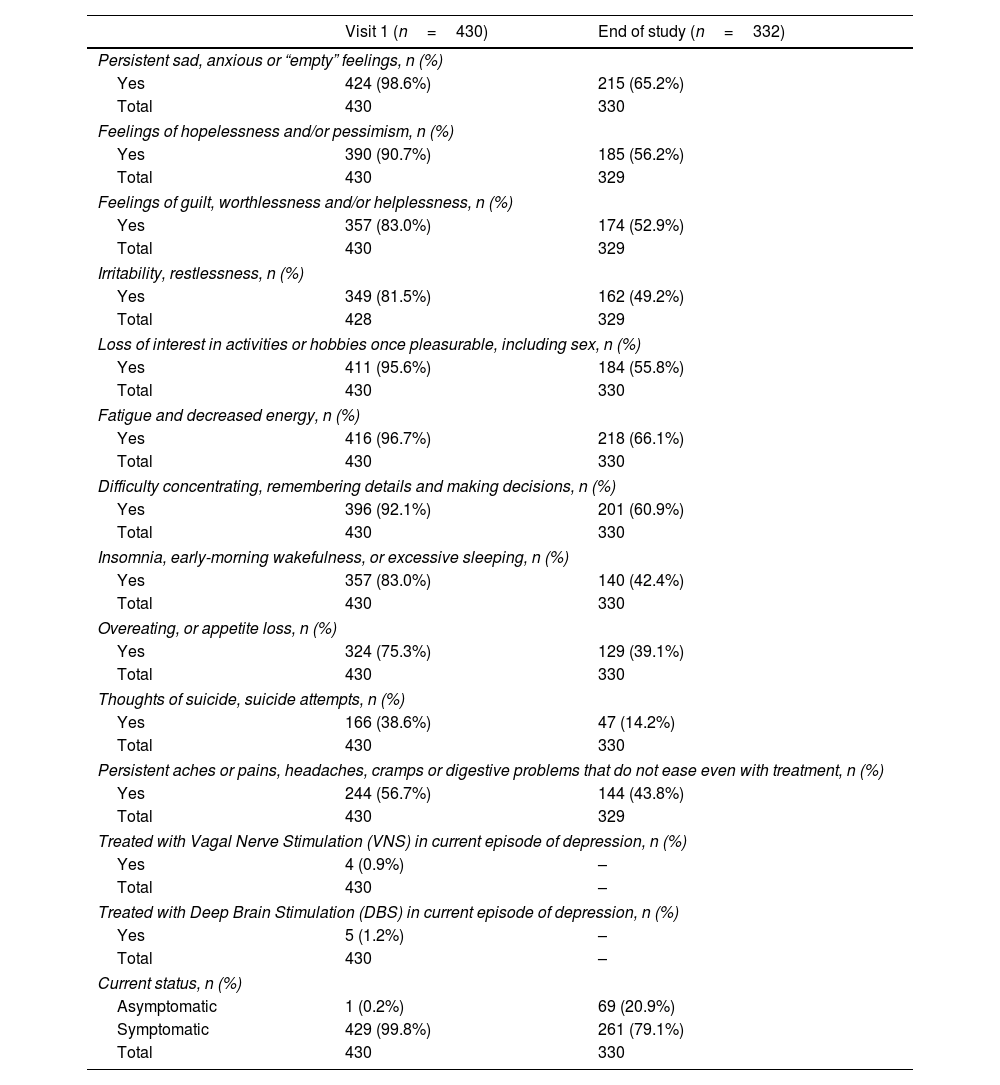

Symptom evolution over 1 yearResults on symptoms evolution are presented in Table 2. At visit 1, the great majority (96.7%) of patients reported fatigue and decreased energy, persistent sad, anxious or ‘empty’ feeling (98.6%), loss of interest in activities or hobbies once pleasurable, including sex (95.6%) and difficulty concentrating, remembering details and making decisions (92.1%). The proportion of symptomatic patients decreased after one year (from 99.8% to 79.1%), but most relevant symptoms of TRD persisted. More than 50% of the patients report TRD related symptoms in most categories, such as persistent sad, anxious or “empty” feelings, feelings of hopelessness and/or pessimism, feelings of guilt, worthlessness and/or helplessness, loss of interest in activities or hobbies once pleasurable, including sex, fatigue and decreased energy, as well as difficulty concentrating, remembering details and making decisions. Almost 15% of the patients still reported thoughts of suicide, and/or suicide attempts after 1-year of SOC.

Evolution of symptoms among TRD patients over one year of SOC.

| Visit 1 (n=430) | End of study (n=332) | |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent sad, anxious or “empty” feelings, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 424 (98.6%) | 215 (65.2%) |

| Total | 430 | 330 |

| Feelings of hopelessness and/or pessimism, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 390 (90.7%) | 185 (56.2%) |

| Total | 430 | 329 |

| Feelings of guilt, worthlessness and/or helplessness, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 357 (83.0%) | 174 (52.9%) |

| Total | 430 | 329 |

| Irritability, restlessness, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 349 (81.5%) | 162 (49.2%) |

| Total | 428 | 329 |

| Loss of interest in activities or hobbies once pleasurable, including sex, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 411 (95.6%) | 184 (55.8%) |

| Total | 430 | 330 |

| Fatigue and decreased energy, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 416 (96.7%) | 218 (66.1%) |

| Total | 430 | 330 |

| Difficulty concentrating, remembering details and making decisions, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 396 (92.1%) | 201 (60.9%) |

| Total | 430 | 330 |

| Insomnia, early-morning wakefulness, or excessive sleeping, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 357 (83.0%) | 140 (42.4%) |

| Total | 430 | 330 |

| Overeating, or appetite loss, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 324 (75.3%) | 129 (39.1%) |

| Total | 430 | 330 |

| Thoughts of suicide, suicide attempts, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 166 (38.6%) | 47 (14.2%) |

| Total | 430 | 330 |

| Persistent aches or pains, headaches, cramps or digestive problems that do not ease even with treatment, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 244 (56.7%) | 144 (43.8%) |

| Total | 430 | 329 |

| Treated with Vagal Nerve Stimulation (VNS) in current episode of depression, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 4 (0.9%) | – |

| Total | 430 | – |

| Treated with Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) in current episode of depression, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 5 (1.2%) | – |

| Total | 430 | – |

| Current status, n (%) | ||

| Asymptomatic | 1 (0.2%) | 69 (20.9%) |

| Symptomatic | 429 (99.8%) | 261 (79.1%) |

| Total | 430 | 330 |

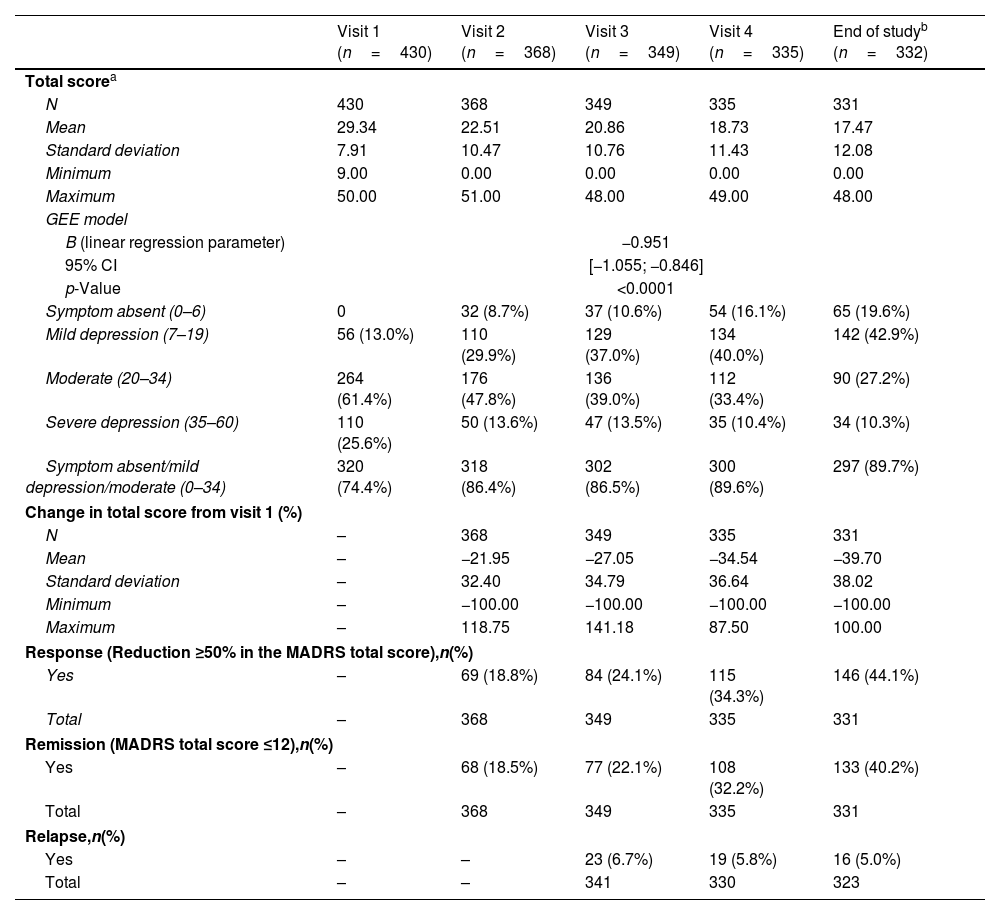

The average MADRS score at visit 1 was 29.3 (range: 9–50) – Table 3. MADRS total score varied significantly over time (p<0.0001), with a mean monthly variation of 0.95 points (B=−0.951).

Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale (MADRS) over a 1-year follow-up with SOC.

| Visit 1 (n=430) | Visit 2 (n=368) | Visit 3 (n=349) | Visit 4 (n=335) | End of studyb (n=332) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total scorea | |||||

| N | 430 | 368 | 349 | 335 | 331 |

| Mean | 29.34 | 22.51 | 20.86 | 18.73 | 17.47 |

| Standard deviation | 7.91 | 10.47 | 10.76 | 11.43 | 12.08 |

| Minimum | 9.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Maximum | 50.00 | 51.00 | 48.00 | 49.00 | 48.00 |

| GEE model | |||||

| B (linear regression parameter) | −0.951 | ||||

| 95% CI | [−1.055; −0.846] | ||||

| p-Value | <0.0001 | ||||

| Symptom absent (0–6) | 0 | 32 (8.7%) | 37 (10.6%) | 54 (16.1%) | 65 (19.6%) |

| Mild depression (7–19) | 56 (13.0%) | 110 (29.9%) | 129 (37.0%) | 134 (40.0%) | 142 (42.9%) |

| Moderate (20–34) | 264 (61.4%) | 176 (47.8%) | 136 (39.0%) | 112 (33.4%) | 90 (27.2%) |

| Severe depression (35–60) | 110 (25.6%) | 50 (13.6%) | 47 (13.5%) | 35 (10.4%) | 34 (10.3%) |

| Symptom absent/mild depression/moderate (0–34) | 320 (74.4%) | 318 (86.4%) | 302 (86.5%) | 300 (89.6%) | 297 (89.7%) |

| Change in total score from visit 1 (%) | |||||

| N | – | 368 | 349 | 335 | 331 |

| Mean | – | −21.95 | −27.05 | −34.54 | −39.70 |

| Standard deviation | – | 32.40 | 34.79 | 36.64 | 38.02 |

| Minimum | – | −100.00 | −100.00 | −100.00 | −100.00 |

| Maximum | – | 118.75 | 141.18 | 87.50 | 100.00 |

| Response (Reduction ≥50% in the MADRS total score),n(%) | |||||

| Yes | – | 69 (18.8%) | 84 (24.1%) | 115 (34.3%) | 146 (44.1%) |

| Total | – | 368 | 349 | 335 | 331 |

| Remission (MADRS total score ≤12),n(%) | |||||

| Yes | – | 68 (18.5%) | 77 (22.1%) | 108 (32.2%) | 133 (40.2%) |

| Total | – | 368 | 349 | 335 | 331 |

| Relapse,n(%) | |||||

| Yes | – | – | 23 (6.7%) | 19 (5.8%) | 16 (5.0%) |

| Total | – | – | 341 | 330 | 323 |

TRD, Treatment Resistant Depression; GEE, Generalized estimating equation; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

One quarter (25.6%) of the patients had severe depression at visit 1. At the end of study, the proportion of patients with severe depression was 10.3%, and moderate depression still afflicted 27.2% of the patients. Overall, symptoms were still present in 80.4% of the patients at the end of study.

Only 44.1% of the patients achieved a response (reduction≥50% in the MADRS total score) at the end of study visit. Around 5% of the TRD sample showed clinically diagnosed relapse at the end of study visit after 1-year of SOC, and remission was not achieved by almost 60% of the patients.

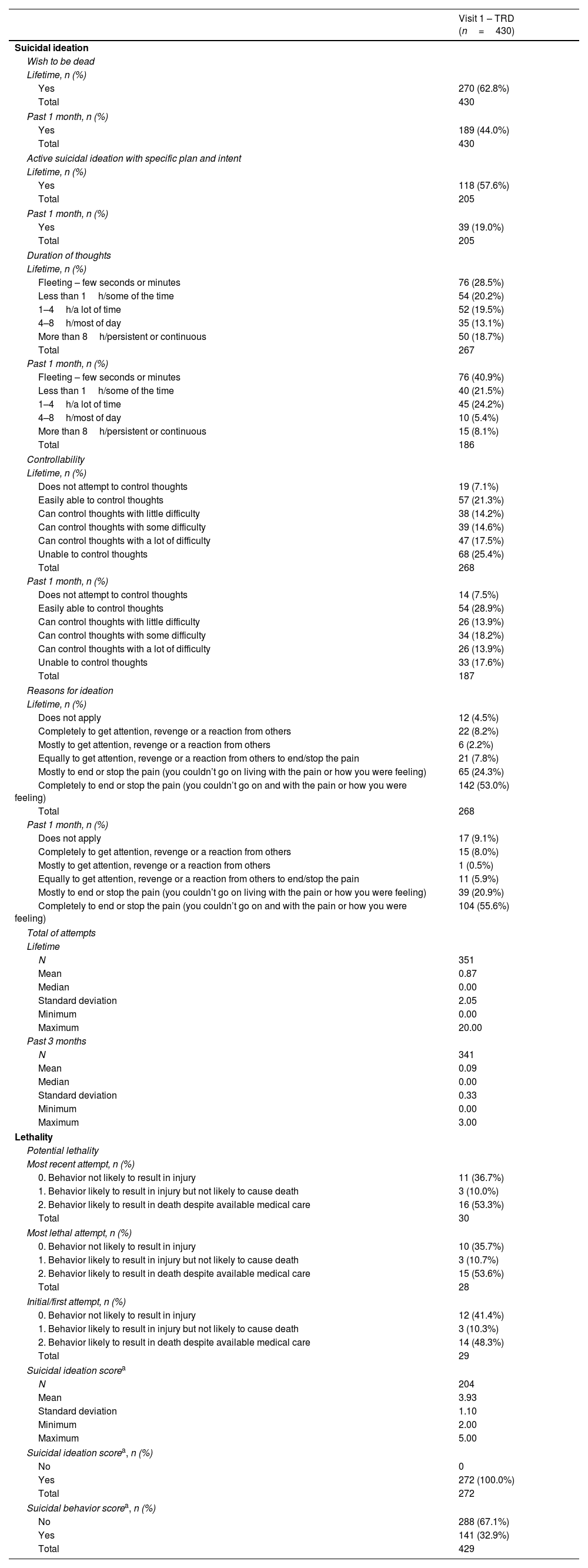

Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)At visit 1, 62.8% of the TRD patients wished to be dead (lifetime) and 44.0% in past month (Table 4). During the follow up, wish to be dead was reported by 32.9% of the patients at visit 2 and 22.7% at the end of the study, considering the evolution since last visit (Table 5). This underlines that a significant proportion of patients still wished to be dead after 1-year of SOC. Also of note is the proportion of patients (10.8%) with persistent/continuous suicidal ideation after 1-year. More than half (57.6%) of TRD patients had active suicidal ideation with specific plan and intent (lifetime), 19% in the past 1 month. Overall, during the study, around 55% of the patients reported suicidal ideation. Also, 23.4% of the sample developed treatment-emergent suicidal ideation – both compared to recent history and to all prior clinical history.

TRD patients scores in Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS) at baseline.

| Visit 1 – TRD (n=430) | |

|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation | |

| Wish to be dead | |

| Lifetime, n (%) | |

| Yes | 270 (62.8%) |

| Total | 430 |

| Past 1 month, n (%) | |

| Yes | 189 (44.0%) |

| Total | 430 |

| Active suicidal ideation with specific plan and intent | |

| Lifetime, n (%) | |

| Yes | 118 (57.6%) |

| Total | 205 |

| Past 1 month, n (%) | |

| Yes | 39 (19.0%) |

| Total | 205 |

| Duration of thoughts | |

| Lifetime, n (%) | |

| Fleeting – few seconds or minutes | 76 (28.5%) |

| Less than 1h/some of the time | 54 (20.2%) |

| 1–4h/a lot of time | 52 (19.5%) |

| 4–8h/most of day | 35 (13.1%) |

| More than 8h/persistent or continuous | 50 (18.7%) |

| Total | 267 |

| Past 1 month, n (%) | |

| Fleeting – few seconds or minutes | 76 (40.9%) |

| Less than 1h/some of the time | 40 (21.5%) |

| 1–4h/a lot of time | 45 (24.2%) |

| 4–8h/most of day | 10 (5.4%) |

| More than 8h/persistent or continuous | 15 (8.1%) |

| Total | 186 |

| Controllability | |

| Lifetime, n (%) | |

| Does not attempt to control thoughts | 19 (7.1%) |

| Easily able to control thoughts | 57 (21.3%) |

| Can control thoughts with little difficulty | 38 (14.2%) |

| Can control thoughts with some difficulty | 39 (14.6%) |

| Can control thoughts with a lot of difficulty | 47 (17.5%) |

| Unable to control thoughts | 68 (25.4%) |

| Total | 268 |

| Past 1 month, n (%) | |

| Does not attempt to control thoughts | 14 (7.5%) |

| Easily able to control thoughts | 54 (28.9%) |

| Can control thoughts with little difficulty | 26 (13.9%) |

| Can control thoughts with some difficulty | 34 (18.2%) |

| Can control thoughts with a lot of difficulty | 26 (13.9%) |

| Unable to control thoughts | 33 (17.6%) |

| Total | 187 |

| Reasons for ideation | |

| Lifetime, n (%) | |

| Does not apply | 12 (4.5%) |

| Completely to get attention, revenge or a reaction from others | 22 (8.2%) |

| Mostly to get attention, revenge or a reaction from others | 6 (2.2%) |

| Equally to get attention, revenge or a reaction from others to end/stop the pain | 21 (7.8%) |

| Mostly to end or stop the pain (you couldn’t go on living with the pain or how you were feeling) | 65 (24.3%) |

| Completely to end or stop the pain (you couldn’t go on and with the pain or how you were feeling) | 142 (53.0%) |

| Total | 268 |

| Past 1 month, n (%) | |

| Does not apply | 17 (9.1%) |

| Completely to get attention, revenge or a reaction from others | 15 (8.0%) |

| Mostly to get attention, revenge or a reaction from others | 1 (0.5%) |

| Equally to get attention, revenge or a reaction from others to end/stop the pain | 11 (5.9%) |

| Mostly to end or stop the pain (you couldn’t go on living with the pain or how you were feeling) | 39 (20.9%) |

| Completely to end or stop the pain (you couldn’t go on and with the pain or how you were feeling) | 104 (55.6%) |

| Total of attempts | |

| Lifetime | |

| N | 351 |

| Mean | 0.87 |

| Median | 0.00 |

| Standard deviation | 2.05 |

| Minimum | 0.00 |

| Maximum | 20.00 |

| Past 3 months | |

| N | 341 |

| Mean | 0.09 |

| Median | 0.00 |

| Standard deviation | 0.33 |

| Minimum | 0.00 |

| Maximum | 3.00 |

| Lethality | |

| Potential lethality | |

| Most recent attempt, n (%) | |

| 0. Behavior not likely to result in injury | 11 (36.7%) |

| 1. Behavior likely to result in injury but not likely to cause death | 3 (10.0%) |

| 2. Behavior likely to result in death despite available medical care | 16 (53.3%) |

| Total | 30 |

| Most lethal attempt, n (%) | |

| 0. Behavior not likely to result in injury | 10 (35.7%) |

| 1. Behavior likely to result in injury but not likely to cause death | 3 (10.7%) |

| 2. Behavior likely to result in death despite available medical care | 15 (53.6%) |

| Total | 28 |

| Initial/first attempt, n (%) | |

| 0. Behavior not likely to result in injury | 12 (41.4%) |

| 1. Behavior likely to result in injury but not likely to cause death | 3 (10.3%) |

| 2. Behavior likely to result in death despite available medical care | 14 (48.3%) |

| Total | 29 |

| Suicidal ideation scorea | |

| N | 204 |

| Mean | 3.93 |

| Standard deviation | 1.10 |

| Minimum | 2.00 |

| Maximum | 5.00 |

| Suicidal ideation scorea, n (%) | |

| No | 0 |

| Yes | 272 (100.0%) |

| Total | 272 |

| Suicidal behavior scorea, n (%) | |

| No | 288 (67.1%) |

| Yes | 141 (32.9%) |

| Total | 429 |

Longitudinal analysis of Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS) – Visit 2, Visit 3, Visit 4 and end of study visit.

| Visit 2 (n=368) | Visit 3 (n=349) | Visit 4 (n=335) | End of study (n=332) | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation – since last visit | |||||

| Wish to be dead, n (%) (Q1) | |||||

| Yes | 121 (32.9%) | 89 (25.5%) | 90 (26.9%) | 75 (22.7%) | – |

| Total | 368 | 349 | 335 | 331 | – |

| Active suicidal ideation with specific plan and intent, n (%) (Q5) | |||||

| Yes | 20 (36.4%) | 5 (10.6%) | 10 (21.3%) | 13 (28.3%) | – |

| Total | 55 | 47 | 47 | 46 | – |

| Suicidal ideationa, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 121 (32.9%) | 90 (25.8%) | 90 (26.9%) | 75 (22.7%) | 229 (54.5%) |

| Total | 368 | 349 | 335 | 331 | 420 |

| Suicidal ideation scoreb | |||||

| N | 368 | 349 | 335 | 331 | – |

| Mean | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.56 | – |

| Median | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | – |

| Standard deviation | 1.30 | 1.05 | 1.19 | 1.27 | – |

| Minimum | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | – |

| Maximum | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | – |

| Duration of thoughts, n (%) | |||||

| Fleeting – few seconds or minutes | 50 (41.3%) | 25 (27.8%) | 31 (34.4%) | 19 (25.7%) | – |

| Less than 1h/some of the time | 28 (23.1%) | 26 (28.9%) | 20 (22.2%) | 17 (23.0%) | – |

| 1–4h/a lot of time | 20 (16.5%) | 18 (20.0%) | 21 (23.3%) | 21 (28.4%) | – |

| 4–8h/most of day | 9 (7.4%) | 9 (10.0%) | 9 (10.0%) | 9 (12.2%) | – |

| More than 8h/persistent or continuous | 14 (11.6%) | 12 (13.3%) | 9 (10.0%) | 8 (10.8%) | – |

| Total | 121 | 90 | 90 | 74 | – |

| Controllability, n (%) | |||||

| Does not attempt to control thoughts | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (2.2%) | 5 (5.6%) | 4 (5.4%) | – |

| Easily able to control thoughts | 39 (32.2%) | 21 (23.3%) | 22 (24.4%) | 14 (18.9%) | – |

| Can control thoughts with little difficulty | 22 (18.2%) | 21 (23.3%) | 18 (20.0%) | 12 (16.2%) | – |

| Can control thoughts with some difficulty | 23 (19.0%) | 27 (30.0%) | 21 (23.3%) | 19 (25.7%) | – |

| Can control thoughts with a lot of difficulty | 24 (19.8%) | 9 (10.0%) | 9 (10.0%) | 14 (18.9%) | – |

| Unable to control thoughts | 11 (9.1%) | 10 (11.1%) | 15 (16.7%) | 11 (14.9%) | – |

| Total | 121 | 90 | 90 | 74 | – |

| Reasons for ideation, n (%) | |||||

| Does not apply | 6 (5.0%) | 6 (6.7%) | 1 (1.1%) | 4 (5.3%) | – |

| Completely to get attention, revenge or a reaction from others | 8 (6.6%) | 5 (5.6%) | 4 (4.5%) | 2 (2.7%) | – |

| Mostly to get attention, revenge or a reaction from others | 7 (5.8%) | 2 (2.2%) | 2 (2.2%) | 2 (2.7%) | – |

| Equally to get attention, revenge or a reaction from others to end/stop the pain | 8 (6.6%) | 7 (7.8%) | 5 (5.6%) | 3 (4.0%) | – |

| Mostly to end or stop the pain (you couldn’t go on living with the pain or how you were feeling) | 21 (17.4%) | 19 (21.1%) | 9 (10.1%) | 13 (17.3%) | – |

| Completely to end or stop the pain (you couldn’t go on and with the pain or how you were feeling) | 71 (58.7%) | 51 (56.7%) | 68 (76.4%) | 51 (68.0%) | – |

| Total | 121 | 90 | 89 | 75 | – |

| Treatment-emergent suicidal ideation compared to recent history, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | – | – | – | – | 89 (23.4%) |

| Total | – | – | – | – | 380 |

| Treatment-emergent serious suicidal ideation compared to recent history, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | – | – | – | – | 23 (6.1%) |

| Total | – | – | – | – | 380 |

| Emergence of serious suicidal ideation compared to recent history, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | – | – | – | – | 2 (0.5%) |

| Total | – | – | – | – | 380 |

| Emergence of suicidal behavior compared to all prior history, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | – | – | – | – | 6 (1.6%) |

| Total | – | – | – | – | 380 |

| Treatment-emergent suicidal ideation compared to all prior history, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | – | – | – | – | 89 (23.4%) |

| Total | – | – | – | – | 380 |

| Emergence of serious suicidal ideation compared to all prior history, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | – | – | – | – | 2 (0.5%) |

| Total | – | – | – | – | 380 |

| Treatment-emergent serious suicidal ideation compared to all prior history, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | – | – | – | – | 9 (2.4%) |

| Total | – | – | – | – | 380 |

| Risk of suicide, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | – | – | – | – | 230 (56.9%) |

| Total | – | – | – | – | 404 |

The most frequent reason for suicidal ideation was completely to end or stop the pain, with 53% in lifetime and 55.6% in the last month. The total attempts in lifetime ranged between 0 and 20 (mean of 0.87) and between 0 and 3 (mean 0.09) in the last 3 months prior to visit 1. Approximately 14% of the patients had suicidal behavior in their lifetime and 5.8% in the past 3 months. Interestingly, the last visit showed an increase, in some of the dimensions, compared to the previous visits, concerning reasons for ideation.

Regarding potential lethality, 53.3% had behavior likely to result in death despite available medical care in the most recent attempt, 53.6% in the most lethal attempt and 48.3% in the first attempt.

Based on information of visit 1, the Suicidal behavior score was computed and showed that 32.9% of TRD patients were scored as “yes”, while 100% of the patients scored “yes” on Suicidal ideation score.

DiscussionThe TRAL study aimed to provide a broad epidemiological picture of MDD and TRD in LatAm, since evidence was scarce, as seen in previous publications.30,31 The present work reports on a 1-year longitudinal analysis of the subset of TRD patients to describe clinical features and outcomes in this setting including suicidality outcomes.

Clinical response (MADRS) was observed in 44% of the TRD patients, consistently increasing over time from month 3 (visit 2) to month 12 (last visit). In addition, the proportion of symptomatic patients after one year was still considerably high (80.4%). These findings indicate that there are medical unmet needs, specifically the availability of more efficacious treatment options for TRD patients. The clinical improvement in depression symptomatology observed in this study is aligned with other reports.33–36 Symptomatology such as “thoughts of suicide/suicide attempts”, “insomnia, early-morning wakefulness, or excessive sleeping” and “overeating, or appetite loss”, were among the most noticeable results following SOC. Patients included in this longitudinal phase were managed at regional reference psychiatric center, supervised by experts, with robust clinical protocols. Nevertheless, the proportion of patients reporting the most representative symptoms at baseline (“fatigue and decreased energy, persistent sad, anxious or ‘empty’ feeling”, “loss of interest in activities or hobbies once pleasurable, including sex”, and “difficulty concentrating, remembering details and making decisions”) remained significant after one year. The known comorbidity with anxiety could have been a confound, since it accounts for a significant part of the symptomatology.37–40

Almost 60% of the patients did not achieve remission (MADRS), which is lower than reported in the STAR-D and other studies.41,42 The remission rates steadily increased over time during the follow-up. Relapse rates also decreased over time, achieving 5% at month 12. One should note that the definition regarding clinical outcomes (response, remission or relapse) in TRD is not universal,8 with different scales, instruments and criteria being adopted for that purpose. Therefore, one should be cautious when comparing these MADRS results – a standardized and clinically validated measure – with studies which use a different set of measures. This adds to the level of evidence provided by TRAL in identifying unmet needs in the treatment of TRD.

Suicidal thoughts were one of the symptoms with a most noticeable reduction, in-line with the global results obtained with C-SSRS. Suicidal ideation/intent/behaviors were significantly less frequent over time, with a clear reduction in death wish. These results based on the use of SOC are less significant compared to research with novel therapies,43–46 in which the reduction of suicidal ideation was more evident. The risk of suicide on a longitudinal assessment (C-SSRS) remained over 50% in TRD patients after the follow-up, consistent with previous research,47 and aligned with the results obtained for the longitudinal assessment of suicidal ideation. Active suicidal ideation with specific plan and intent still afflicts some of the patients at the end of study. The concomitant nature of suicidality and depression in TRD patients is a common concern and more predominant than in MDD patients.16 This is one of the most severe consequences of TRD and actions should be undertaken to address this, as suggested in previous TRAL publications (Corral et al., 2022; Soares et al., 2021).

Other C-SSRS results show that almost one-quarter of the TRD patients had treatment-emergent suicidal ideation and 6.1% treatment-emergent serious suicidal ideation, aligned with previous data from the use of C-SSRS.47–51 The high prevalence of suicidal ideation after 1-year of treatment on reference psychiatric centers reinforces TRD's burden and the need for more effective treatments for these patients.

TRAL31 and other studies52 showed that TRD patients had more severe clinical presentations than MDD, highlighting the significant burden of the disease. While the proportion of TRD patients severely depressed (MADRS) dropped from 25% at visit 1, approximately 1 in 10 patients remained severely depressed at the end of follow-up, illustrating a substantial unmet need with serious potential consequences.

As expected, most of the patients were female. Previous research showed that women are more prone to develop MDD and other depressive disorders and that estrogen may play a key role.53 Conversely, women show lower treatment gap and recognize symptoms easier in self-report scales and clinical assessments, offering some explanation to the results.54

LimitationsTRAL provides a relevant depiction of the results of SOC for TRD patients in LatAm, involving some of the most relevant psychiatric treatment centers in the region from the four countries. Sample size is adequate in size and the heterogeneity of contexts supports inferences from the present data for LatAm. However, country-specific inferences should be performed with caution, as the sample size was not calculated with that goal in mind. Also, this is not a population-based study, as the inclusion criteria limits the profile of patients included (i.e. MDD patients under regular follow-up at reference treatment sites in the region). Also, inferences on clinical response for the SOC must consider that all therapies were included in the analysis, and no comparisons between therapies were performed. Moreover, baseline disease severity and number of years since MDD diagnosis were not controlled for in the longitudinal analyses. However, this can also be considered a strength, since the heterogenous nature of the clinical protocols better depicts real-world practice and the challenges

Final remarksPhase 1 of the TRAL study and the current insights from phase 2 should influence public health policies in the coming years. Although not perfectly representative of the region, these data are robust and provide important insights, both in the prevention and management of TRD. Moreover, this real-world evidence – increasingly important in the context of public health policies – suggests that considerable efforts should be placed in developing and/or increasing availability of novel therapies that show promising results in increasing clinical response. Patient education – to increase treatment adherence and earlier search for help – is essential to promote swifter diagnosis – in which training non-specialized physicians is also key – after symptoms onset and subsequent treatment initiation. Primary care physicians should articulate with psychiatrists on the best treatment protocol since symptoms onset, and avoid referring to psychiatry only when the clinical presentation of the symptoms became serious or significantly resistant to therapeutic options. Current results also highlight some key clinical insights. Regardless of the severity of the disease, TRD is more frequent than could be expected. Given the treatment resistant pattern and refractory nature of TRD, this should always be considered a serious condition.

ConclusionsStandard-of care offers some relevant clinical benefits but fails to deliver on the overall unmet need in the treatment of TRD patients in LatAm. The persistence of symptoms observed among TRD patients after one year under SOC underlines the burden of the disease. Beyond the most common and manageable symptoms of depression, current treatment protocols fail to deliver on the management of this life-threatening condition as suicidality is not fully addressed and remains significant over time. Participants of this study were patients of reference psychiatry centers, therefore lack of access to treatment cannot be considered a primary reason for the low remission rates, reinforcing the limitations of current treatments for TRD. Treatment optimization should be pursued, including the introduction of novel therapies with promising clinical results. Reducing the burden of the condition should consider timely diagnosis, access to specialized care, and the development of therapeutic options that limit disease progression and consequently, the resulting disability. Ensuring that all patients are closely monitored by specialists is important, but must be accompanied by better therapeutic options, ensuring a long-term rationalization of costs with the management of the disease. The burden of disease is substantial and current unmet needs undermine TRD patients’ ability to achieve a clinical response that allows stable, fulfilling and safe living and full integration as productive members of society. The authors hope these results act as call-to action for all relevant stakeholders in order to promote better clinical outcomes in these at-risk patients.

Limitations- 1.

This is not a population-based study, which may present a somewhat biased depiction of disease severity;

- 2.

The heterogeneity of treatment protocols at the sites limits the inferences on the effectiveness of a specific standard of care protocol;

- 3.

Disease severity at baseline or the time from diagnosis were not considered as co-variates in the longitudinal analysis.

Data will be made available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

FundingTRAL (Treatment-Resistant Depression in America Latina) study was funded by Janssen LatAm, a filial of Janssen, Inc., which was involved in the approval of the manuscript. CTI provided medical writing and editorial support funded by Janssen LatAm, a filial of Janssen, Inc. Authors received honorarium as investigators in the TRAL study.

Conflict of interestsMAC received a research grant from Janssen Pharmaceutical.

CTT has been working on consulting for or serving on the advisory board on Jansen Cilag Farmaceutica, Lundbeck do Brasil, Servier do Brasil, Abbott Laboratórios do Brasil, Medley Farmaceutica, Takeda Distribuidora, SEM, Torrent do Brasil, and receiving grant or research support from Abbott laboratórios do Brasil, Libbs Farmaceutica, Lundbeck do Brasil, Medley Farmaceutica, Ache Laboratorios Farmaceuticos, Torrent do Brasil, Biolab Sanus Farmaceutica, Laboratorios Pfizer, Servier do Brasil, Apsen Farmaceutica, EMS.

LMAB declares no conflict of interests.

MVD declares having contributed as a speaker, advisor and participant in symposiums, courses, workshops and congresses, invited by Janssen, having received, for such functions, the corresponding professional fees. Speaker at the Update Conference on Mood Disorders, sponsored by Gador Laboratories, and held in Buenos Aires in 2019. Such participation involved professional fees for his functions. Speaker, with previously scheduled fees, at the symposium organized by Lundbeck Laboratories on Update on Depression, at the conference held in Tandil, Province of Buenos Aires, in 2019. The edition by Editorial Polemos of the book on “Depression of Difficult Management”, carried out in collaboration with other authors in 2017, was sponsored by Raffo Laboratories.

RMC declares having received support for research and fees as a speaker from Janssen Cilag Argentina.

LDAS declares being a speaker for Shire-Takeda, Lundbeck, Asofarma, Armstrong, Janssen, Servier, and Novartis, received investigation grants from Pfizer, Janssen Lilly and Roche. Also had an advisory role for Armstrong, Acadia, Sanfer, Psicofarma, and Servier, none related to the current work.

ES: Is currently conducting a clinical trial sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceutical.

GK: Is currently an employee at Janssen Pharmaceutical.

PC: Is currently an employee at Janssen Pharmaceutical.

The authors would like to thank our patients and their families for the consent and time dedicated to this study, as well as the teams involved in the study conduction and data collection.

Clinical Trial & Consulting Services (CTI) provided statistical analysis support to the TRAL funded by Janssen LatAm.

Diogo Morais from Clinical Trial & Consulting Services (CTI) provided medical writing assistance and editorial support with this manuscript, funded by Janssen LatAm. Janssen LatAm participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the content. All the authors had access to all relevant data and participated in writing, review, and approval of this manuscript.