Electronic ecological momentary assessment (EMA) can provide precise information regarding day-to-day functioning of patients overcoming some of the limitations of usual clinical evaluation; however adherence to this methodology might be a major threat. Research and application of EMA concerning clinical settings remains scant. Our goal was to study the user profiles of EMA in a clinical sample of adolescents.

Material and methods209 adolescents following an outpatient mental health treatment accepted to use EMA. They were evaluated in different sociodemographic and clinical variables as well as the use that they made of EMA.

Results39.7% of patients were considered users and 60.3% non-active users. Certain self-harm behaviours were more common in the group of active users, while hyperkinetic disorders were more common in the group of non-active users. A regression analysis revealed that non-suicidal self-injury (OR=2.99) and hyperkinetic disorders (OR=0.51) were related to the use of EMA.

ConclusionThis preliminary study adds novel and promising information about EMA use in clinical practice. Adolescents with self-harm behaviours EMA seem more prone to use this tool. Our study provides support for actively monitoring self-harm behaviours with EMA. Future studies might consider a comprehensive analysis of adherence and EMA data collection.

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is an evaluation method that consists in the collection of certain behaviours, symptoms, and states of the subject in real-time (or shortly after) and in their day-to-day life. This method can help us to better understand and even predict certain behaviours overcoming some of the limitations of usual clinical evaluation in which time with subjects is limited and the information is generally collected retrospectively.1

EMA is not a single method, much less a particular technology, but a collection of methods that share the aforementioned characteristics.1 Assessment scheduling in EMA can vary based on the study aim. So-called ‘event-contingent’ assessments are linked to events, such as occasions when the subject is about to undertake or has just undertaken a particular behaviour.2 Another approach to EMA is to schedule assessments for certain times, which is known as ‘time-based assessments’.2

Methods of assessment can range from the use of paper and pencil to the use of the most advanced technologies. The use of new technologies such as web-based methodology is replacing conventional methods (paper version).3 This implies a greater precision and realism of data since they permit the verification of the time of entry, which implies a more detailed analysis of compliance.

Compliance seems to be better when using new technologies1,4,5 and preference for electronic versus more traditional paper diaries has been found even in older subjects.6 Electronic EMA has been successfully applied in different populations such us low socioeconomic status patients7 and subjects with psychiatric disorders such as psychosis,8,9 affective disorders,10,11 substance use disorders1,12 or self-injurer populations13 among others. However, subject self-reports required from some EMA and the rejection towards new technologies of some subjects are major threats to electronic EMA adherence.

Adolescents might be considered a target population for electronic EMA since they are very prone to use new technologies such as mobile phone applications although there is still scant literature regarding adherence to EMA on this population. Electronic EMA seems a powerful tool to use with subjects who engage in risky behaviours that start during adolescence and that are frequent in clinical population such as self-harm behaviours.14 These behaviours are not always reported during face-to-face consultation. However, evidence suggests that self-harming youth make more use of new technologies (social networks) and that they are utilized as a medium to communicate with and to seek social support from others.15

A recent review about compliance with mobile EMA protocols in children and adolescents found an average compliance rate of 78%, not finding differences between clinical and non-clinical samples.16 The average compliance in this review is defined as suboptimal and it is under adult's compliance found in other review studies, which is over 80%.17,18 In their review16 they included 42 studies but only four studies were carried out on mental health samples. The aim of the study was the examination of the relationship between adolescent compliance and study design factors such as length of EMA protocols and sampling frequency. Some of the studies also took into account the influence of some personal variables such as age19–23 gender,19–25 disease status19-24 or intelligence quotient (IQ).23 From these variables only IQ was positively associated with compliance.23

Apart from analyzing EMA design factors related to adherence to this methodology, it is also important to specifically examine which personal factors are related to the usage of electronic EMA assessment. Barrigon et al.,26 carried out a study concerning this issue in adult clinical population finding that active users were younger and more frequently diagnosed with anxiety related disorders than non-active users. They were more likely to report thoughts about death and suicide and had experienced more stressful life events than non-active users. Rickwood et al.,27 tried to provide a comprehensive profile of young people seeking web-based mental health support instead of face-to-face. They found that more web-based mental health support users were female and they tended to be older. They also found that a higher percentage of web-based support users presented high or very high levels of psychological distress, but they were at an earlier stage of illness on other indicators of clinical presentation compared with centre-based counselling clients.

Although EMA has gained broad acceptability in research in the last years, there is little knowledge concerning clinical practice and user profiles. To the best of our knowledge the study of Barrigon et al.,26 is the only one that specifically studies this issue, and there are not studies regarding this issue in clinical adolescent population. Examining clinical and demographic profiles of adolescents who will and won’t respond to EMA would add knowledge to the present literature. Additionally, it might help in research and clinical practice with adolescents since it would allow us to apply EMA in a more targeted and efficient way. It would have important benefits in clinical practice, in which time with patients is limited. Regarding clinical characteristics we hypothesize that patients diagnosed with hyperkinetic disorders (International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision – ICD-10) might be less inclined to use EMA since the avoidance of mental effort and the emotional dysregulation typical of these disorders might interfere the use of EMA.28 Given that adult active users were more likely to report thoughts about death and suicide than non-active users in a clinical sample26 and concerning the study about the frequent use of new technologies in self-harming youth,15 we hypothesize that adolescents reporting self-harm ideas or behaviours, including NSSI, will be more active in the use of EMA.

As we mentioned before, adolescents might be a target population for EMA use; however, it is important to describe how it can be tailored to characteristics of the patient and applied efficiently. The aim of this study is to determine the sociodemographic and clinical differences between users and non-active users of a new electronic EMA tool in a sample of adolescents followed in outpatient mental health services.

Material and methodsParticipantsSubjects were recruited from the Child and Adolescent Outpatient Psychiatric Services of Jiménez Díaz Foundation and Infanta Elena University Hospitals (Madrid, Spain) from November 1st 2015 to October 31st 2018. The sample of patients who were offered the use of EMA was consecutive. After describing the study, written informed consent was obtained from patients and parents or legally authorized representatives who agreed to participate. Subjects under 12 years old, subjects over 18 years old, and/or those who lacked the capacity to comprehend the questionnaires used in this study were excluded. The Jiménez Díaz Foundation Ethics Committee approved the study.

Instruments and procedureQuestionnaires and other clinical information were registered using “MeMind” (www.memind.net) a web application that was developed to merge different data sources, including patient and caregiver inputs. The MeMind application had two interfaces, one for clinicians: the “electronic health record (EHR) view” and another for patients: the “EMA view”. The EMA view was also available as a mobile phone application (MeMind).

Clinicians made a first evaluation collecting the following information in the EHR: sociodemographic data, stressful life events and psychosocial problems, ICD-10 mental disorder diagnoses,29 illness severity measured by the Clinical Global Impression scale – CGI30 and the Children's Global Assessment Scale –CGAS,31 and questions regarding any lifetime self-harm thoughts or behaviours: NSSI, thoughts about suicide, suicide plans and suicide attempts.

After the clinician's part was filled out, EMA view for patients was activated. Patients were given a user number and a password in order to access MeMind. They had to complete the following questionnaires the day in which EMA was first activated: the 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5)32 as a measure of subjective psychological well-being, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)33 as a measure of mental health, and a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) as a measure of satisfaction with different life areas. The electronic versions used for WHO-5 and GHQ-12 have been considered equivalent to the paper-and-pencil version.34

Subsequently, patients had to connect to the EMA interface once a day (at the end of the day). No reminder (e.g. e-mail, sms or pop-ups) was made in this first step of MeMind development. In this “diary EMA” patients answered the WHO-5 and the five VAS questions regarding satisfaction with oneself, family, friends, studies and leisure, during the day. Additionally, they had a free-text area (“notes”) that they could use at any moment when engaging in their daily life activities.

Patients did not receive any economic incentive for participation and circumstances and setting of the study were very similar to real world conditions.

Statistical analysisFor analysis purposes, subjects were divided into two groups: users (patients who accessed the “diary EMA” at least once) and non-active users (patients who never accessed the “diary EMA”).

According to Barrigón et al.26 the group was divided based on just one access to the diary EMA since one of our first purposes was to identify the patients that showed initial interest to EMA and were more prone to use the tool. Although considering these criteria we cannot strictly speak of “adherence”, the adherent group would be considered the users group and the non-adherent group would be considered the non-active users group. The type of adherence (bigger, smaller, partial) was not assessed in this preliminary study.

Univariate analyses using chi-square and t-test were performed to compare characteristics between the two groups. The variables analyzed were: sociodemographic (age, sex, ethnicity, academic performance, separation of parents or divorce) and clinical (diagnosis, self-harm behaviour, substance use, stressful life events, illness severity, general mental health index, subjective psychological well-being, and satisfaction with different life areas).

Subsequently, a regression analysis was carried out to establish the magnitude of the association between characteristics of patients that were different between groups and the use of EMA.

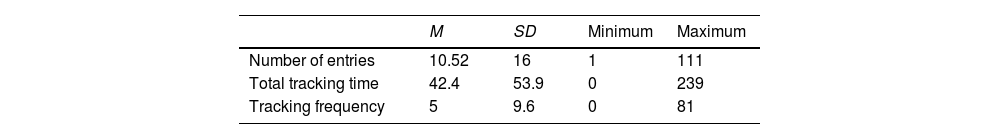

ResultsThere were 209 patients that accepted participation in the study. From them, 83 (39.7%) accessed the diary EMA interface (users), while 126 (60.3%) did not access the diary EMA (non-active users). Information regarding EMA users access is in Table 1.

Users access to EMA.

| M | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of entries | 10.52 | 16 | 1 | 111 |

| Total tracking time | 42.4 | 53.9 | 0 | 239 |

| Tracking frequency | 5 | 9.6 | 0 | 81 |

Note. Number of entries (number of times a patient enters EMA). Total tracking time (days from the EMA activation until the last entry). Tracking frequency (patients make an entry every “X” days).

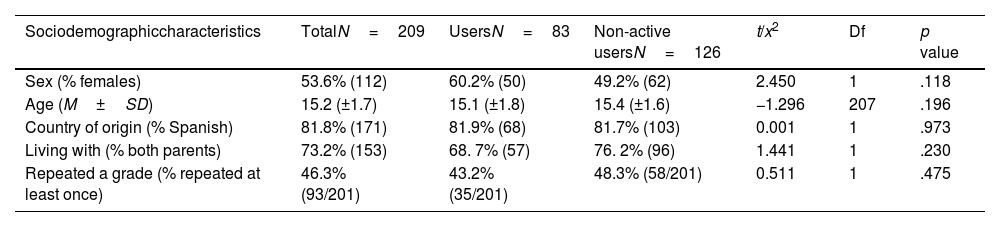

Participants were (53.6%) women and (46.4%) men, with a mean age of 15 years old (SD=1.7). Most subjects were Spanish (81.8%) and lived with both parents (73.2%). 46.3% of participants had repeated a grade at least once. There were no differences between users and non-active users in these sociodemographic characteristics (Table 2).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

| Sociodemographiccharacteristics | TotalN=209 | UsersN=83 | Non-active usersN=126 | t/x2 | Df | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% females) | 53.6% (112) | 60.2% (50) | 49.2% (62) | 2.450 | 1 | .118 |

| Age (M±SD) | 15.2 (±1.7) | 15.1 (±1.8) | 15.4 (±1.6) | −1.296 | 207 | .196 |

| Country of origin (% Spanish) | 81.8% (171) | 81.9% (68) | 81.7% (103) | 0.001 | 1 | .973 |

| Living with (% both parents) | 73.2% (153) | 68. 7% (57) | 76. 2% (96) | 1.441 | 1 | .230 |

| Repeated a grade (% repeated at least once) | 46.3% (93/201) | 43.2% (35/201) | 48.3% (58/201) | 0.511 | 1 | .475 |

Note. p values significant at the p<.05 level (bilateral).

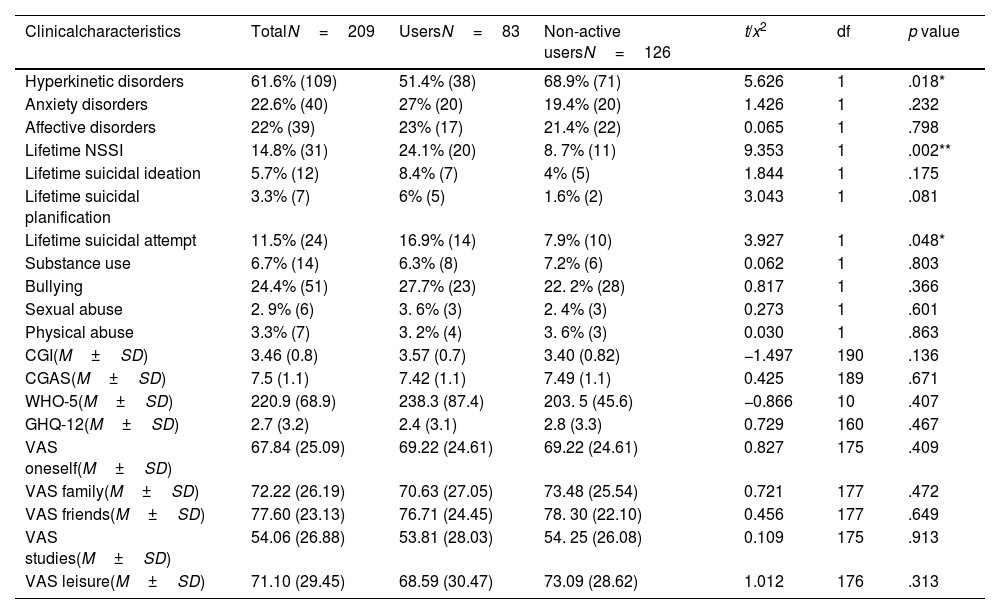

Table 3 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the total sample and compares users and non-active users.

Clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Clinicalcharacteristics | TotalN=209 | UsersN=83 | Non-active usersN=126 | t/x2 | df | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperkinetic disorders | 61.6% (109) | 51.4% (38) | 68.9% (71) | 5.626 | 1 | .018* |

| Anxiety disorders | 22.6% (40) | 27% (20) | 19.4% (20) | 1.426 | 1 | .232 |

| Affective disorders | 22% (39) | 23% (17) | 21.4% (22) | 0.065 | 1 | .798 |

| Lifetime NSSI | 14.8% (31) | 24.1% (20) | 8. 7% (11) | 9.353 | 1 | .002** |

| Lifetime suicidal ideation | 5.7% (12) | 8.4% (7) | 4% (5) | 1.844 | 1 | .175 |

| Lifetime suicidal planification | 3.3% (7) | 6% (5) | 1.6% (2) | 3.043 | 1 | .081 |

| Lifetime suicidal attempt | 11.5% (24) | 16.9% (14) | 7.9% (10) | 3.927 | 1 | .048* |

| Substance use | 6.7% (14) | 6.3% (8) | 7.2% (6) | 0.062 | 1 | .803 |

| Bullying | 24.4% (51) | 27.7% (23) | 22. 2% (28) | 0.817 | 1 | .366 |

| Sexual abuse | 2. 9% (6) | 3. 6% (3) | 2. 4% (3) | 0.273 | 1 | .601 |

| Physical abuse | 3.3% (7) | 3. 2% (4) | 3. 6% (3) | 0.030 | 1 | .863 |

| CGI(M±SD) | 3.46 (0.8) | 3.57 (0.7) | 3.40 (0.82) | −1.497 | 190 | .136 |

| CGAS(M±SD) | 7.5 (1.1) | 7.42 (1.1) | 7.49 (1.1) | 0.425 | 189 | .671 |

| WHO-5(M±SD) | 220.9 (68.9) | 238.3 (87.4) | 203. 5 (45.6) | −0.866 | 10 | .407 |

| GHQ-12(M±SD) | 2.7 (3.2) | 2.4 (3.1) | 2.8 (3.3) | 0.729 | 160 | .467 |

| VAS oneself(M±SD) | 67.84 (25.09) | 69.22 (24.61) | 69.22 (24.61) | 0.827 | 175 | .409 |

| VAS family(M±SD) | 72.22 (26.19) | 70.63 (27.05) | 73.48 (25.54) | 0.721 | 177 | .472 |

| VAS friends(M±SD) | 77.60 (23.13) | 76.71 (24.45) | 78. 30 (22.10) | 0.456 | 177 | .649 |

| VAS studies(M±SD) | 54.06 (26.88) | 53.81 (28.03) | 54. 25 (26.08) | 0.109 | 175 | .913 |

| VAS leisure(M±SD) | 71.10 (29.45) | 68.59 (30.47) | 73.09 (28.62) | 1.012 | 176 | .313 |

CGI: Clinical Global Impression scale. Scores range from 1 (not ill) to 7 (extremely ill). CGAS: Children's Global Assessment Scale. Scores range from 1 (constant need for supervision) to 10 (optimal functioning). WHO-5: World Health Organization Well-Being Index. Scores range from 0 (lower well-being) to 500 (greater well-being). GHQ-12: General Health Questionnaire. Scores range from 0 (absence of psychological disturbance) to 12 (severe psychological disturbance). VAS: Visual Analogue Scale. Scores range from 0 (lower satisfaction) to 100 (greater satisfaction).

Most patients were diagnosed with hyperkinetic disorders (F90 ICD-10) (61.6%). There were more patients diagnosed with this diagnosis in the group of non-active users (68.9%) than in the group of users (51.4%) (χ2=5.626, p=.018). Anxiety related disorders (F4 ICD-10) (22.6%) and affective disorders (F3 ICD-10) (22%) were also frequent. There were more patients diagnosed with anxiety related disorders in the group of users (27%) than in the group of non-active users (19.4%), however this difference was not statistically significant. According to affective disorders, the percentage of patients in each group was very similar, finding no statistically significant differences between groups.

Regarding self-harm behaviour, there were differences between groups in some specific areas. Users were more likely to report NSSI across lifetime (24.1% of active users) (χ2=9.353, p=.002) and suicidal attempts were also more frequent in the group of users (up to 16.9% of users reported lifetime suicidal attempts) (χ2=3.927, p=0.048). Although lifetime suicidal ideation and suicidal planification were more common in the group of users, these differences were not statistically significant.

Concerning other clinical measures such as substance use, stressful life events, illness severity, general mental health index, subjective psychological well-being and satisfaction with different life areas differences were not found.

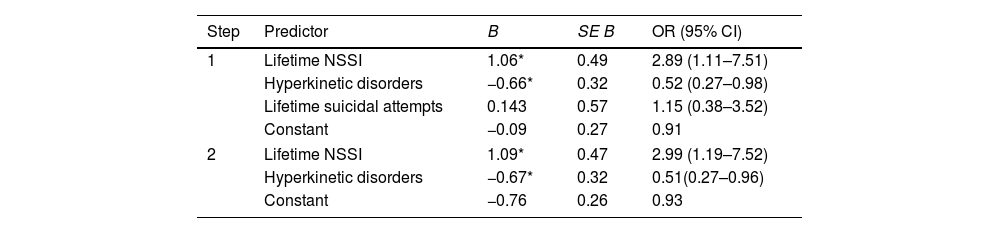

Regression modelWe performed binary logistic regression analyses with all the significant variables as predictors of the EMA user profile. The variables that remained in the model were: “NSSI across lifetime” and “hyperkinetic disorders”. These results suggest a statistically significant relationship between these variables and being an EMA user profile. Patients with “NSSI across lifetime” were more prone to be active users, while patients diagnosed with “hyperkinetic disorders” were more prone to be non-active users. “Lifetime suicidal attempts” was removed from the model in the regression analysis (Table 4).

Summary of logistic regression analyses for variables predicting use of EMA.

| Step | Predictor | B | SE B | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lifetime NSSI | 1.06* | 0.49 | 2.89 (1.11–7.51) |

| Hyperkinetic disorders | −0.66* | 0.32 | 0.52 (0.27–0.98) | |

| Lifetime suicidal attempts | 0.143 | 0.57 | 1.15 (0.38–3.52) | |

| Constant | −0.09 | 0.27 | 0.91 | |

| 2 | Lifetime NSSI | 1.09* | 0.47 | 2.99 (1.19–7.52) |

| Hyperkinetic disorders | −0.67* | 0.32 | 0.51(0.27–0.96) | |

| Constant | −0.76 | 0.26 | 0.93 | |

OR: odds ratio.

In our study, 39.7% of the samples were considered users. This figure is above that found in the similar study carried out in adult clinical population (20.5%).26 The difference between figures is in line with studies showing a better acceptance of internet-based interventions among younger people.26,35

Our findings indicate that NSSI and suicidal attempts were significantly more common in the group of users, while hyperkinetic disorders were more common in the group of non-active users. Univariate analyses confirmed this relationship; however, the logistic regression analysis did not confirm it in the case of suicidal attempts, that did not predict EMA use by its own.

According to our hypothesis we found that the patients diagnosed with hyperkinetic disorders were less prone to use EMA. However, a recent systematic review concerning the use of EMA in ADHD concluded that EMA could be successfully implemented with patients diagnosed with ADHD.36 The majority of the studies were carried out in samples of children up to 12 years old and/or their parents, and they indicate that parent involvement may be critical to maintaining child adherence rates. Only one study was conducted in an adolescent sample.37 In this four-day study the decliners of the study received more deviant parent ADHD ratings than did the participants, although the final adherence of the non-decliner group was high (80%). The use of EMA in adolescent population diagnosed with “hyperkinetic disorders” seems more complex but not useless. Appropriate adaptations such as parent involvement,36,38 shorter periods of assessment,37 the use of implicit models of EMA,39 or more general facilitators such as training of participants and compliance monitoring/check-ins combined with compliance-based incentives 40 might improve the usage in this population.

A positive relationship between self-harm behaviours and the use of EMA was found, which is connected to previous reports. Barrigón et al.,26 found that patients with suicidal thoughts and plans were more likely to be EMA active users in adult population. In our study we found that different self-harm behaviours (NSSI, suicidal ideation, suicidal planification and suicidal attempt) were more common in the group of users, although only NSSI predicted being a user. Fortunately our sample size of adolescents with lifetime suicidal ideation (5.7%) and lifetime suicidal planification (3.3%) was small. On the other hand, NSSI in adolescence is a common behaviour, indicating prevalence around 21.7% in outpatient clinical samples14 (15% in our sample). The relationship between NSSI and suicide is not clear but it has been hypothesized that NSSI is a gateway facilitating adolescents to attempt suicide.41 Both behaviours frequently coexist42 and NSSI seems to be an important risk factor for suicide after adjusting for other risk factors.43 All this might be in relation to the fact that only these two self-harm behaviours (lifetime NSSI and lifetime suicidal attempts) were related to the use of EMA in our study, however we can’t draw conclusions regarding this issue, since the frequency of self-harm behaviours was low and it goes beyond the scope of this work. It is also curious that there were more lifetime suicide attempters (11.5%) than lifetime suicide ideators or planificators in our sample. Impulsivity is a core characteristic of adolescence, which might explain the impulsive nature of suicidal attempts during this period. Moreover, information regarding suicidal ideation or planification is easier to omit (less evident) than past suicidal attempts.

There are different factors that might be related to the association between self-harm behaviour and EMA use. As it was mentioned before15 self-harming youth make more use of new technologies in order to communicate to others. Additionally, Rickwood et al.,27 found that a higher percentage of young web-based support users presented high or very high levels of psychological distress but they were at an earlier stage of illness. Adolescents with NSSI are supposed to suffer from high levels of psychological distress and they might be – according to the aforementioned theories regarding NSSI as a gateway to suicide41 – in an “early” stage of illness. Alternative explanations might be related to the fact that caregiver involvement and monitoring could be higher in patients that have a history of self-harm behaviour.

This preliminary study adds novel and promising information about EMA use in clinical practice. In our sample, adolescents with self-harm behaviours were more active in the use of EMA tool than other adolescents, which provide support for the use of EMA in this population.

A recent paper concerning the current challenges in research on suicide advocates the use of EMA.44 It might be very useful since accurate monitoring of NSSI with EMA could help with identifying the events recorded in the NSSI population that could predict NSSI and/or suicidal attempts during follow-up.

Our study has some limitations. Given that the use of the tool “MEmind” in the clinical setting is relatively time consuming for clinicians, optimal data collection was at times complicated. The sample size was small and diagnosis variability was limited also. We should acknowledge that certain behaviours had a low frequency – such us some self-harm behaviours –; hence we must be cautious when drawing conclusions and take these results as provisional.

The fact that we used a naturalistic clinical adolescent sample also limits the generalization of our results, however this makes the results ecological and adapted to the real clinical setting. In relation to the EMA interface for adolescents it still has some limitations such as lack of pop-ups or reminders, which make adherence more complicated. The fact that patients did not have any direct incentive for completing EMA also makes adherence more complicated.

ConclusionsNevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that specifically examines the personal variables that are in relation to EMA use in adolescents assisted in outpatient mental health services. This study has important research and clinical implications since it provides clues as to the application of EMA in varying clinical subpopulations.

Future studies might consider the inclusion of bigger samples and the examination of potential differences between high frequency and low frequency users, as well as EMA tool improvements.

FundingThis study has been partly funded by Carlos III (ISCIII PI16/01852), Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional de Drogas (20151073), American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (LSRG-1-005-16), the Madrid Regional Government (B2017/BMD-3740 AGES-CM 2CM; Y2018/TCS-4705 PRACTICO-CM) and Structural Funds of the European Union. MINECO/FEDER (’ADVENTURE’, id. TEC2015-69868-C2-1-R) and MCIU Explora Grant ‘aMBITION’ (id. TEC2017-92552-EXP).

Conflict of interestsNone declared.