The Latin American Consensus Conference on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) was convened in 2004 by the Inter American Association of Gastroenterology and the Inter American Association of Digestive Endoscopy in recognition of the high prevalence of GERD and the challenges posed by the definition, diagnosis and management of this entity in Latin America.1 The implementation of consensus guidelines poses two main challenges: ensuring timely dissemination of the guidelines to all stakeholders, while, in conjunction, maintaining a current evidence base such that the guidelines remain relevant to clinical practice. A review of the literature published after the Latin American consensus revealed a detailed consideration of the definitions of GERD from a global perspective2; in contrast, there were no significant publications addressing important features of diagnosis. It was not, therefore, felt necessary to update the Latin American consensus with respect to the definition or diagnosis of GERD. The current update to the Latin American GERD consensus will, therefore, concentrate on a review of the literature pertaining to the treatment of GERD in Latin America.

Ideally, evidence-based clinical guidelines should consider only high quality studies. However, there are few areas in healthcare in which there is sufficient evidence-based research to guide professionals in their decisions, and in some instances appropriate studies might never be available. Diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are frequently introduced and incorporated into medical practice without rigorous assessment of their quality. While some procedures may turn out to be beneficial, evaluation of others shows that they fail to produce the expected benefits or even that they are ineffective or harmful. Unfortunately, once those procedures have been introduced as the standard of care, their use may be difficult to discontinue; therefore, it is essential to determine the effectiveness of any diagnostic method or treatment before it becomes widely adopted.

Dissemination of the concepts resulting from a consensus is equally important, so that clinicians can implement the guidelines into their daily practice, allowing us to adjust any conclusions according to the outcomes obtained by practitioners.

The aim of the current update was to identify all relevant GERD treatment studies published since the review conducted for the Latin American consensus and, in the areas for which new data were available, to update the evidence and modify the conclusions and recommendations, when necessary.

MethodsTwo experts in evidence-based medicine (G.T. and M.L.C.) undertook a systematic review (systematic search, critical appraisal and summary of the evidence) of treatment for GERD, based on an extensive, systematic review of the literature for the 3-year period from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2006 to supplement the literature search conducted for the original Latin American publication. A systematic review and meta-analysis were performed but, unlike in the previous guideline, there was no formal voting to reach a consensus.

The overall review strategy was identical to that used for the original publication; a systematic, recursive literature search was carried out using Medline, the Cochrane Library and the Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Literature Database. The present guideline is intended for application in adults with GERD. For this reason, the search strategies aimed to retrieve studies performed in this age group; publications on Barrett's esophagus, extra-esophageal reflux disease, atypical GERD symptoms, and pediatric GERD were excluded. Studies addressing medical, endoscopic or surgical therapy were included if they assessed any of the following outcomes: heartburn relief, healing of esophagitis, heartburn remission, esophagitis relapse, and heartburn relapse; quality of life, satisfaction, and length of hospital stay were also included for studies of surgical treatment. The search was restricted to articles published in English, French or Spanish. The main search terms included gastroesophageal reflux (MeSH term), heartburn (MeSH term), and esophagitis (MeSH term); the types of publication included were meta-analyses, reviews, and randomized controlled trials.

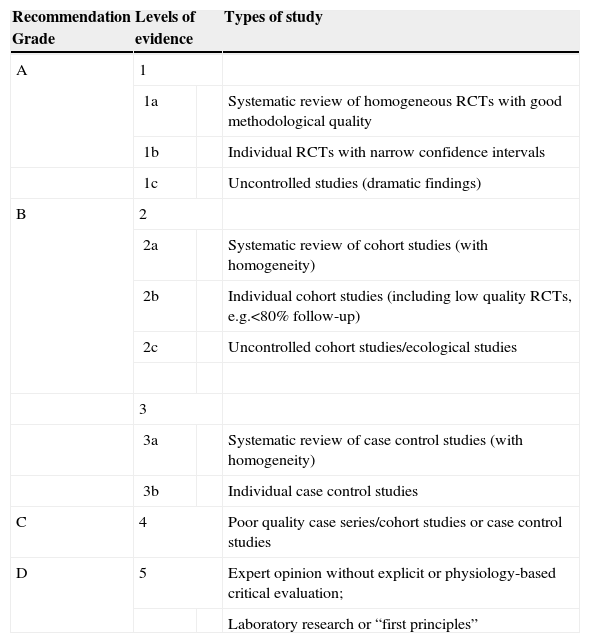

The quality of the methodology was evaluated based on the users’ guide for medical literature for therapeutic and prevention studies.3 Levels of evidence and recommendation grades were defined according to the classification of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine4 (Table 1). Grade A is “highly recommended” and is applied to studies with grade 1 evidence (systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials or large randomized controlled trials with a low probability of bias or without bias).

Grade of recommendation and levels of evidence

| Recommendation Grade | Levels of evidence | Types of study | |

| A | 1 | ||

| 1a | Systematic review of homogeneous RCTs with good methodological quality | ||

| 1b | Individual RCTs with narrow confidence intervals | ||

| 1c | Uncontrolled studies (dramatic findings) | ||

| B | 2 | ||

| 2a | Systematic review of cohort studies (with homogeneity) | ||

| 2b | Individual cohort studies (including low quality RCTs, e.g.<80% follow-up) | ||

| 2c | Uncontrolled cohort studies/ecological studies | ||

| 3 | |||

| 3a | Systematic review of case control studies (with homogeneity) | ||

| 3b | Individual case control studies | ||

| C | 4 | Poor quality case series/cohort studies or case control studies | |

| D | 5 | Expert opinion without explicit or physiology-based critical evaluation; | |

| Laboratory research or “first principles” | |||

RCT: Randomized clinical trial.

The results of the intervention studies were synthesized in a meta-analysis with the Software Review Manager Version 4.2.5 and presented as relative risks (RR) and relative risk reductions (RRR), with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI).

The data on treatment outcomes are presented in the following treatment categories: lifestyle and dietary interventions, short-term pharmacological therapy, long-term pharmacological therapy, endoscopic therapy, and surgical therapy. These categories are subdivided further, for pharmacological therapy, according to whether or not patients have confirmed erosive esophagitis – patients treated empirically, without prior endoscopy, or those with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) and patients with erosive esophagitis – and to the type of therapy – antacids, alginates and sucralfate, histamine H2-receptor antagonists (H2-RA), prokinetics and proton pump inhibitors (PPI). In addition, on-demand therapy is discussed separately in the section on maintenance therapy, as the outcome measures are somewhat different and the study populations included patients with and without esophagitis. For each section, the update includes an overview of the background information, the outcome of the updated literature search, the implications for any recommendations and the current recommendation incorporating any necessary revisions.

The target users of the guideline will be gastroenterologists, family physicians, nurses, practitioners and all professionals involved in the care of GERD patients. The results will be presented in national meetings in Latin America and in the Panamerican Congress in 2010.

Potential barriers to implementation of the recommendations may include the costs of medications, insurance plans, the availability of diagnostic tools and drugs, and language and cultural barriers. Costs were not addressed.

ResultsThe literature search, for the period from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2006, identified 136 studies and 32 systematic reviews relevant to the treatment of GERD; of these, 79 met the specified inclusion criteria.

1. Diet and lifestyle changes

Overview: The major change in this area is increasing epidemiological evidence for an association between obesity and GERD and its complications.6 This change is of particular importance given the increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in many parts of the world, including Latin America.7 A recent study, in randomly-selected women participating in the Nurses’ Health Study, indicates that weight gain is associated with an increased risk of GERD symptoms.8 However, there is limited, if any, data to confirm that lifestyle changes, dietary modification or weight loss improve GERD symptoms or healing of esophagitis,9 although there are some reports that the marked weight loss achieved by bariatric surgery may reduce reflux symptoms in some individuals.10

Review outcome: No new relevant studies on dietary or lifestyle modifications (e.g. raising the bed head during sleep) were published during the review period.11–25

Impact on recommendations: None.

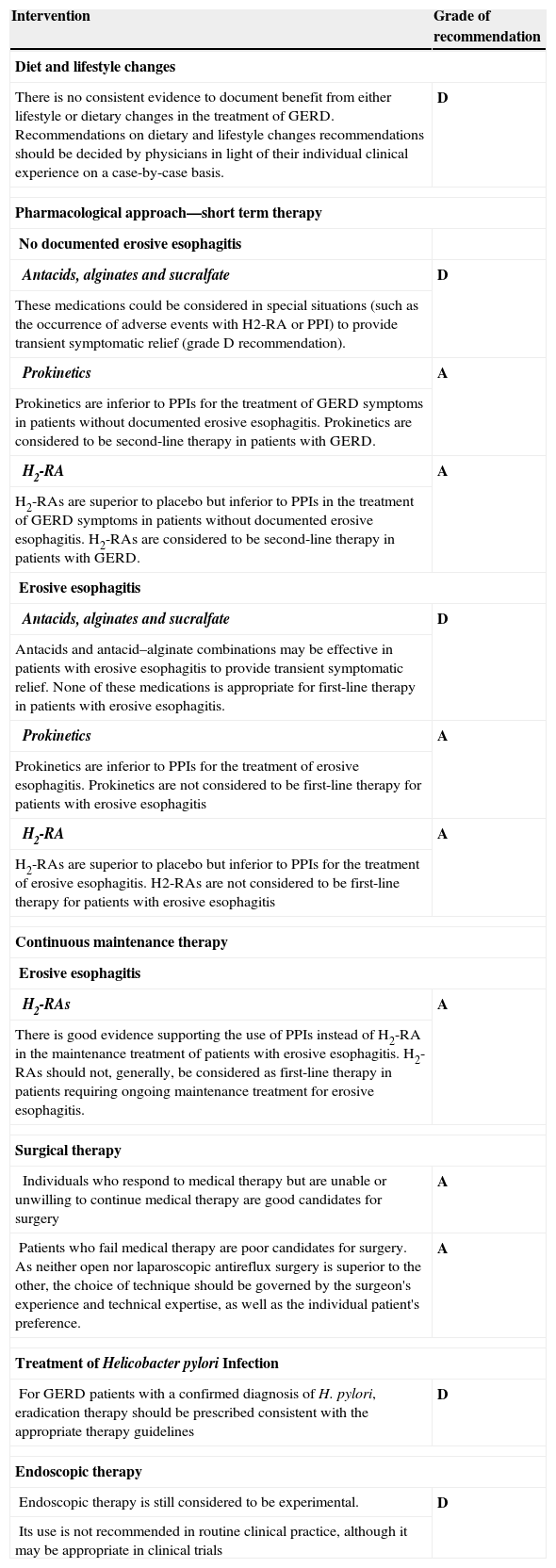

Recommendation: The recommendation is unchanged with respect to the 2004 Consensus (see Table 2)

Recommendations remaining unchanged to those of the previous 2004 Consensus

| Intervention | Grade of recommendation |

| Diet and lifestyle changes | |

| There is no consistent evidence to document benefit from either lifestyle or dietary changes in the treatment of GERD. Recommendations on dietary and lifestyle changes recommendations should be decided by physicians in light of their individual clinical experience on a case-by-case basis. | D |

| Pharmacological approach—short term therapy | |

| No documented erosive esophagitis | |

| Antacids, alginates and sucralfate | D |

| These medications could be considered in special situations (such as the occurrence of adverse events with H2-RA or PPI) to provide transient symptomatic relief (grade D recommendation). | |

| Prokinetics | A |

| Prokinetics are inferior to PPIs for the treatment of GERD symptoms in patients without documented erosive esophagitis. Prokinetics are considered to be second-line therapy in patients with GERD. | |

| H2-RA | A |

| H2-RAs are superior to placebo but inferior to PPIs in the treatment of GERD symptoms in patients without documented erosive esophagitis. H2-RAs are considered to be second-line therapy in patients with GERD. | |

| Erosive esophagitis | |

| Antacids, alginates and sucralfate | D |

| Antacids and antacid–alginate combinations may be effective in patients with erosive esophagitis to provide transient symptomatic relief. None of these medications is appropriate for first-line therapy in patients with erosive esophagitis. | |

| Prokinetics | A |

| Prokinetics are inferior to PPIs for the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Prokinetics are not considered to be first-line therapy for patients with erosive esophagitis | |

| H2-RA | A |

| H2-RAs are superior to placebo but inferior to PPIs for the treatment of erosive esophagitis. H2-RAs are not considered to be first-line therapy for patients with erosive esophagitis | |

| Continuous maintenance therapy | |

| Erosive esophagitis | |

| H2-RAs | A |

| There is good evidence supporting the use of PPIs instead of H2-RA in the maintenance treatment of patients with erosive esophagitis. H2-RAs should not, generally, be considered as first-line therapy in patients requiring ongoing maintenance treatment for erosive esophagitis. | |

| Surgical therapy | |

| Individuals who respond to medical therapy but are unable or unwilling to continue medical therapy are good candidates for surgery | A |

| Patients who fail medical therapy are poor candidates for surgery. As neither open nor laparoscopic antireflux surgery is superior to the other, the choice of technique should be governed by the surgeon's experience and technical expertise, as well as the individual patient's preference. | A |

| Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection | |

| For GERD patients with a confirmed diagnosis of H. pylori, eradication therapy should be prescribed consistent with the appropriate therapy guidelines | D |

| Endoscopic therapy | |

| Endoscopic therapy is still considered to be experimental. | D |

| Its use is not recommended in routine clinical practice, although it may be appropriate in clinical trials | |

2. Pharmacological approach – short term therapy

a. No documented erosive esophagitis

i) Antacids, alginates and sucralfate

Overview: Antacids and antacid-alginate combinations are widely used, generally as over-the-counter preparations, for the management of GERD symptoms. Sucralfate is not widely used but, anecdotally, this drug may be prescribed in patients intolerant of or unresponsive to standard acid suppression therapy.

There are some data to indicate that antacid-alginate combinations are effective in short-term symptom control in patients with GERD, but therapeutic gain is small. There are insufficient data to support a recommendation that sucralfate be used for the treatment of GERD. Review Outcome: No relevant studies on antacid, alginates or sucralfate were published during the review period.

Impact on recommendations: None

Recommendation: The recommendation is unchanged with respect to the 2004 Consensus (see Table 2).

ii) Prokinetics

Overview: Medications with prokinetic activity, including metoclopramide, domperidone, cisapride, mosapride and tegaserod have been investigated as sole therapy and in combination with antisecretory medications for the treatment of GERD symptoms. Cisapride and tegaserod have been withdrawn from the market and mosapride is not widely available, leaving metoclopramide and domperidone as the only prokinetic agents available for general use.

Review outcome: No relevant studies were published on prokinetic agents during the review period.

Impact on recommendations: None.

Recommendation: The recommendation is unchanged with respect to the 2004 Consensus (see Table 2).

iii) H2-Receptor antagonists

Overview: H2-RAs are extensively used as over-the-counter and prescription therapy for the treatment of GERD symptoms. These agents are more effective than placebo for the relief of symptoms as empiric therapy and also for NERD; however, they are less effective than PPIs.1,26

Review outcome: No relevant studies on H2-RAs were published during the review period.

Impact on Recommendations: None.

Recommendation: The recommendation is unchanged with respect to the 2004 Consensus (see Table 2).

iv) Proton pump inhibitors

Overview: PPIs are generally accepted to be significantly more effective than placebo, H2-RAs and prokinetics for heartburn relief and general improvement of symptoms in patients without documented erosive esophagitis. Virtually all clinical data are derived from studies using a once-daily PPI and, although there are gastric pH data to show that twice-daily PPIs produce greater acid suppression than once-daily therapy in patients with GERD symptoms,27 there are no clinical data on high-dose PPI therapy in this patient group. Heartburn relief with standard dose omeprazole (20mg daily) was greater than with half-dose omeprazole (10mg daily) but previous studies have reported no differences between distinct doses of esomeprazole (40mg and 20mg) or between esomeprazole (40mg daily) and omeprazole (20mg daily).1

Review Outcome: Only one study comparing PPIs with placebo and utilizing one of the specified outcomes was published during the review period28; this study reported similar results to those of previous studies. Another study, comparing esomeprazole 40mg daily and esomeprazole 20mg daily with placebo29 in uninvestigated GERD patients, reported that esomeprazole reduced nocturnal heartburn, improved sleep quality and enhanced work productivity compared with placebo but that there was no difference between the two doses of esomeprazole.

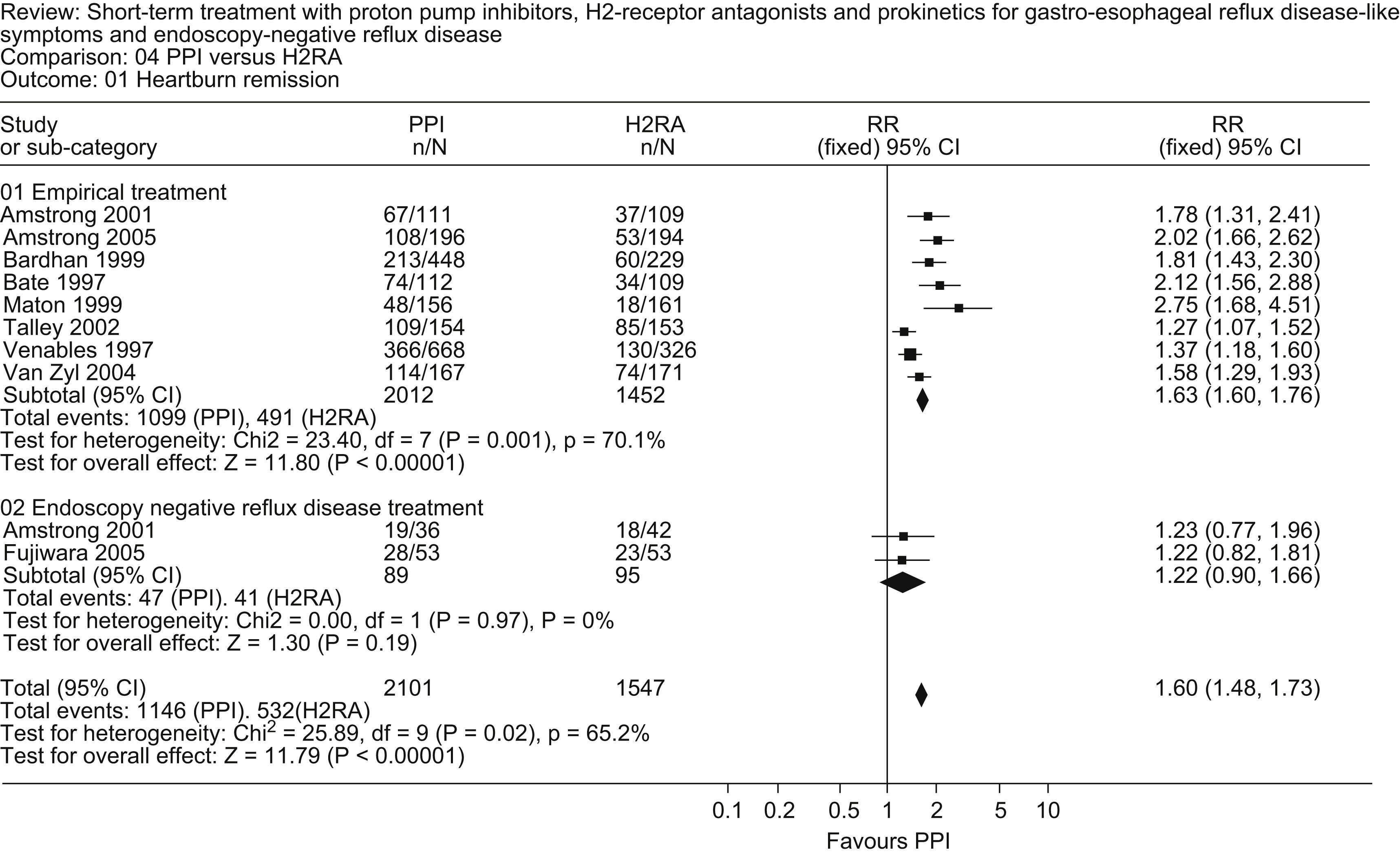

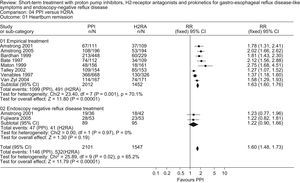

Studies comparing PPIs with H2-RAs published during the review period30–33 confirm the superiority of PPIs for symptom relief in patients without documented erosive esophagitis (Fig. 1).

A study comparing PPIs in patients without documented erosive esophagitis34 reported no difference in symptom relief between esomeprazole (20mg daily) and pantoprazole (20mg daily) with RR values of 1.03 (95%CI: 0.89–1.20) and 1.01 (0.93–1.10) at 2 and 4 weeks, respectively.

Impact on recommendations: None.

Recommendation: PPIs are superior to H2-RAs or prokinetics for the initial management of patients with GERD symptoms but no documented evidence of erosive esophagitis (grade A recommendation). Despite evidence of dose-related differences in acid suppression for individual PPIs and of differences in acid suppression among PPIs, there are no clinical data to show that dose escalation or a change of PPI is associated with a greater effect on symptom relief.

b. Erosive esophagitis

i) Antacids, alginates and sucralfate

Overview: Antacids, antacid-alginate combinations and sucralfate are not generally prescribed or recommended for patients with documented erosive esophagitis, although these drugs are self-administered quite frequently as over-the-counter medications to produce short-term relief in patients taking prescription acid suppression therapy (Ref: Jones. R et al., 2001 APT35).

Review outcome: No relevant studies on antacids, alginates or sucralfate were published during the review period.

Impact on recommendations: None

Recommendation: The recommendation is unchanged with respect to the 2004 Consensus (see Table 2).

ii) Prokinetics

Overview: Medications with prokinetic activity, including metoclopramide, domperidone and cisapride, have been investigated as sole therapy and in combination with antisecretory medications for the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Cisapride and tegaserod have been withdrawn from the market, leaving metoclopramide and domperidone as the only prokinetics available for general use.

Review outcome: No relevant studies comparing prokinetic agents with placebo or other therapies were published during the review period.

Impact on recommendations: None.

Recommendation: The recommendation is unchanged with respect to the 2004 Consensus (see Table 2).

iii) H2-Receptor Antagonists

Overview: H2-RAs are more effective than placebo for the treatment of erosive esophagitis but are less effective than PPIs.

Review outcome: No relevant studies comparing H2-RAs with placebo or other therapies were published during the review period.

Impact on recommendations: None.

Recommendation: The recommendation is unchanged with respect to the 2004 Consensus (see Table 2).

iv) Proton pump inhibitors

Overview: PPIs are generally accepted to be significantly more effective than placebo, H2-RAs and prokinetics for the treatment of erosive esophagitis. These conclusions are based on extensive meta-analyses36 and are supported by numerous recent GERD consensus publications1,37,38. There is continuing controversy as to whether there are any differences among PPIs in terms of clinical outcomes in patients with erosive esophagitis. There is no evidence that the efficacy of PPIs is related to anything other than the degree and duration of acid suppression produced by these drugs. Previous studies have reported that esomeprazole (40mg daily) is more effective than omeprazole (20mg daily) and lansoprazole (30mg daily) in healing erosive esophagitis and relieving reflux symptoms in patients with erosive esophagitis, particularly in those with more severe esophagitis (Los Angeles [LA] grades C and D). Although the differences in outcome are likely to be related to the differing effects of the treatment regimens on acid suppression, the extent to which these differences in outcomes are medication-related or dose-related remains controversial and the absolute magnitude of any difference is difficult to estimate because of the confounding effect of other factors such as esophagitis severity.

Review outcome: The only study39 comparing a PPI with placebo in patients with erosive esophagitis used intravenous pantoprazole and did not evaluate any of the clinical outcomes specified in this analysis. No studies comparing PPIs with H2-RAs or prokinetics for the healing of erosive esophagitis were published during the review period.

However, several studies were published during the review period that compared distinct PPIs in the treatment of erosive esophagitis. A comparison of rabeprazole (20mg daily) and omeprazole (20mg daily) reported no significant differences in healing of esophagitis at 4 and 8 weeks 40; with respect to secondary endpoints, rabeprazole was superior in inducing remission of heartburn and lack of daytime pain.

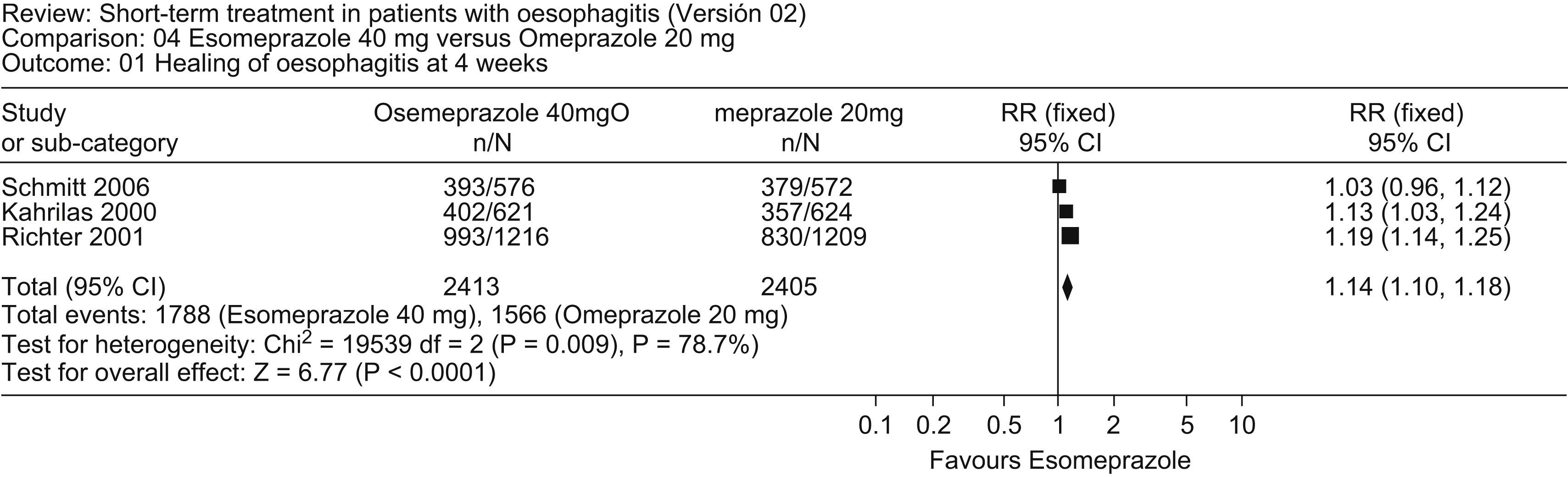

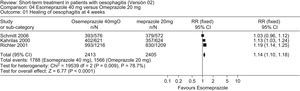

A comparison of esomeprazole (40mg daily) and omeprazole (20mg daily) revealed no overall differences in healing of esophagitis at 4 weeks or 8 weeks,41 although esomeprazole produced healing in a greater proportion of patients with severe esophagitis (LA grade C and D) than did omeprazole. A meta-analysis of this new study with two prior randomized clinical trials42–44 comparing esomeprazole (40mg daily) with omeprazole (20mg daily) in 4818 patients with esophagitis showed that esomeprazole was more effective in producing healing of esophagitis at 4 and 8 weeks and in inducing remission of heartburn at 4 weeks (Fig. 2).

A randomized, controlled trial45 comparing lower dose esomeprazole (20mg daily) with omeprazole (20mg daily) reported no differences between the two PPIs, either in healing of esophagitis at 4 weeks (RR: 0.99; 95%CI: 0.92–1.07) and 8 weeks (1.03; 0.99–1.07) or in remission of heartburn at 4 weeks (1.00; 0.91–1.10).

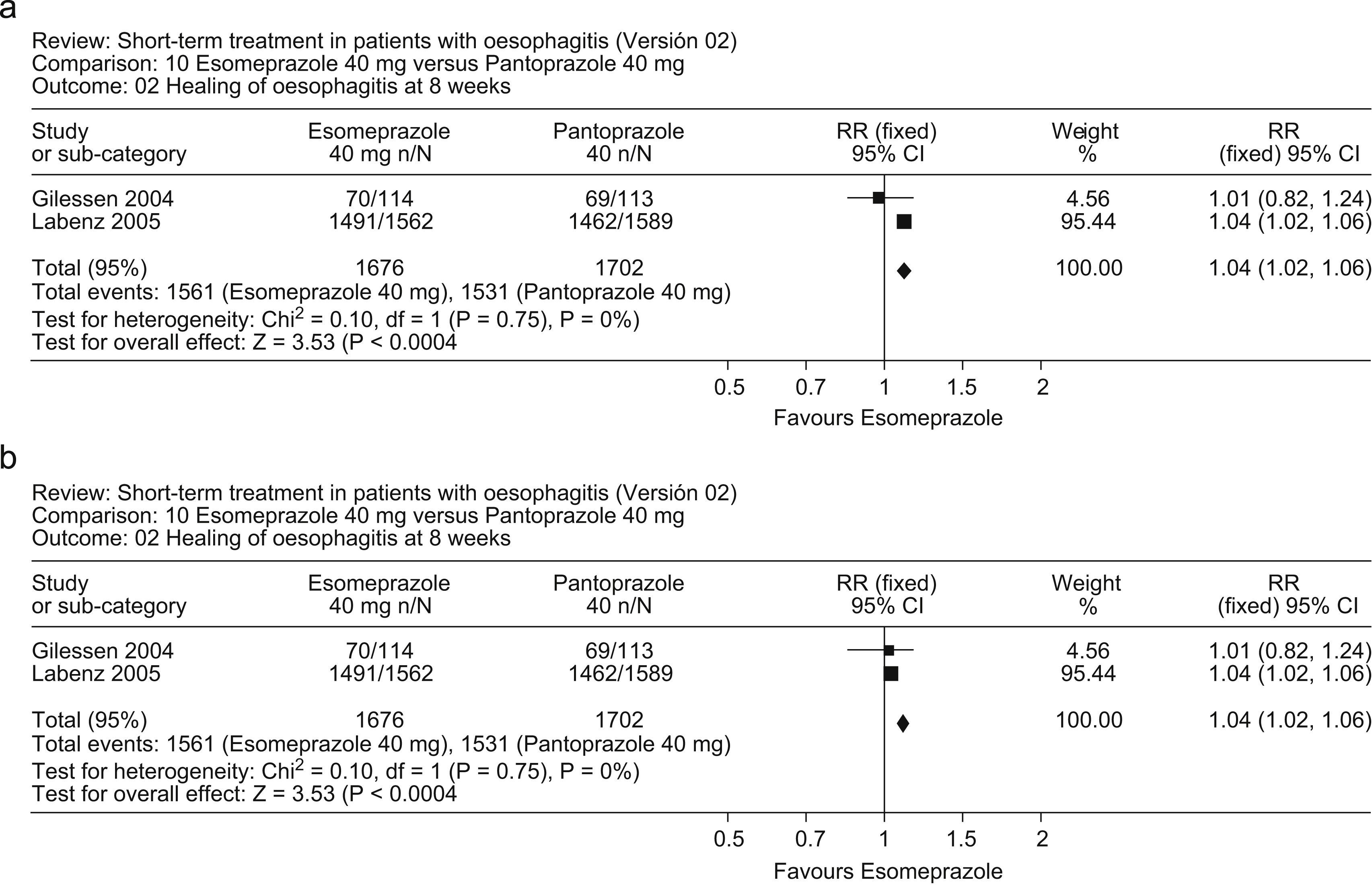

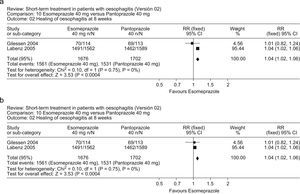

Two randomized, controlled trials comparing esomeprazole (40mg daily) with pantoprazole (40mg daily) in patients with erosive esophagitis provided conflicting results; the first46 reported no differences between the two PPIs, whereas the second, much larger study47 reported that esomeprazole was significantly more effective than pantoprazole. A meta-analysis of these studies (Fig. 3a, b) indicates that esomeprazole was more effective than pantoprazole in healing of esophagitis at 4 weeks (RR: 1.08; 95%CI: 1.04–1.12) and 8 weeks (1.04; 1.02–1.06).

A previous meta-analysis comparing esomeprazole (40mg daily) with other PPIs, including the data reported by Schmitt et al 41, concluded that esomeprazole produced a modest overall benefit in 8-week healing and symptom relief when all patients with erosive esophagitis were considered. The authors noted that the clinical benefit of esomeprazole appears to be negligible in less severe erosive disease but might be important in more severe disease48.

Impact on recommendations: None.

Recommendation: PPIs are more effective than placebo, prokinetics and H2-RAs in healing erosions and providing symptom relief in patients with erosive esophagitis. PPIs should be the initial therapy of choice (4–8 weeks) for erosive esophagitis. There appears to be little difference between PPIs in patients with mild esophagitis (LA grade A and B); however, healing may be produced in a higher proportion of patients with more severe erosive esophagitis (LA grade C and D) with esomeprazole (40mg daily) than with lansoprazole, omeprazole or pantoprazole if they have more severe erosive esophagitis (grade A recommendation).

3. Pharmacological Approach: Long-Term Therapy

Most long-term trials have evaluated the efficacy of continuous maintenance therapy, with daily drug administration, in the prevention of recurrent erosions, documented by endoscopy, or of recurrent reflux symptoms. However, in recent years, a number of studies have evaluated the efficacy of on-demand therapy for the management of recurrent reflux symptoms. This treatment paradigm requires that patients take medication only when they have recurrent symptoms and, as a result, evaluating treatment efficacy by documenting the prevention of recurrent symptoms is not appropriate. Because of concerns that non-continuous therapy would permit continuing esophageal injury, with the possibility of long-term adverse sequelae, most trials have been conducted in patients with NERD, complicating overall assessment of on-demand therapy. However, recent research has studied on-demand therapy in patients with erosive esophagitis, as well as those with NERD. As a result, it was decided that continuous maintenance therapy and on-demand therapy would be reviewed separately in this document.

Continuous maintenance therapya. No documented erosive esophagitis

i) Proton pump inhibitors

Overview: PPIs are generally more effective at preventing relapse of reflux symptoms than placebo, prokinetics or H2-RAs when prescribed as long-term therapy in patients without documented erosive esophagitis. However, the efficacy of long-term therapy depends, in part, on the treatment regimen: on-demand therapy allows patients to take medication as needed, when they have symptoms, intermittent therapy provides fixed-length courses of therapy (typically 2–8 weeks) in the event of symptom recurrence, while continuous maintenance therapy provides for uninterrupted, long-term daily medication intake.

Review outcome: One new study comparing on-demand lansoprazole (15mg daily) with placebo49 in patients with uninvestigated GERD reported that on-demand PPI therapy was superior to placebo with respect to control of heartburn and patient satisfaction. Although this study provided no direct data on heartburn recurrence, a Danish, multicenter, primary care study reported that on-demand therapy with esomeprazole (20mg daily, as needed) was associated with lower costs than intermittent, physician-controlled 2-week or 4-week courses of esomeprazole (40mg daily); on-demand therapy was associated with fewer episodes of relapse than intermittent therapy during the 6-month study but there were no major differences in patient satisfaction.50 However, when on-demand therapy (esomeprazole 20mg daily, as needed) was compared with continuous PPI therapy (esomeprazole 20mg daily), heartburn remission and quality of life were similar for the two PPI regimens, although both were more effective than continuous ranitidine therapy (150mg twice daily).51

Impact on Recommendations: The updated review is consistent with prior data that on-demand PPI therapy is superior to placebo and H2-RAs for long-term therapy in patients without documented erosive esophagitis. Patient outcomes are similar for on-demand, intermittent and continuous long-term therapy, although on-demand therapy may be associated with lower costs.

Recommendation: There is good evidence (type 1) supporting the use of PPIs instead of H2-RAs or prokinetics in the maintenance treatment of patients with GERD without documented erosive esophagitis. Consequently, patients needing ongoing treatment should be offered any PPI as a first choice maintenance therapy (grade A recommendation). The choice of treatment strategy is a matter for discussion between the patient and the physician, after consideration of costs, convenience and treatment aims. There are no data to indicate that one PPI is preferable to another in this patient group (grade D recommendation).

b. Erosive esophagitis

i) Histamine H2-Receptor antagonists

Overview: H2-RAs are widely used in the long-term management of GERD but, although the previous consensus publication noted that famotidine was more effective than placebo in maintaining remission from esophagitis at 6 months (RR: 0.18, 95%CI: 0.09–0.37), tachyphylaxis occurs with H2-RA therapy and consequently these drugs are significantly less effective than PPIs in preventing relapse of erosive esophagitis.

Review outcome: No relevant studies on long-term H2-RA treatment for erosive esophagitis were published during the review period.

Impact on recommendations: None.

Recommendation: The recommendation is unchanged with respect to the 2004 Consensus (see Table 2).

ii) Proton pump inhibitors

Overview: PPIs are the most effective long-term medical therapy for preventing recurrent erosions and reflux symptoms in patients with erosive esophagitis. The 2004 Consensus noted that, although H2-RAs (such as famotidine) are more effective than placebo (RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.37) in maintaining the healing of esophagitis at 6 months, PPIs are more effective than placebo, H2-RAs and prokinetics.

At the 2004 Consensus, it was noted that studies had shown no differences between rabeprazole 10mg and rabeprazole 20mg, rabeprazole 10mg, rabeprazole 20mg and omeprazole 20mg, lansoprazole 30mg and pantoprazole 40mg, lansoprazole 30mg and omeprazole 20mg, pantoprazole 40mg and omeprazole 20mg, pantoprazole 20mg and pantoprazole 40mg or esomeprazole 40mg and esomeprazole 20mg in the maintenance of endoscopic and clinical remission of patients with esophagitis. However, the finding that omeprazole 20mg was superior to omeprazole 10mg in maintaining healing of esophagitis does support the concept that the efficacy of maintenance therapy in this class of medication is related to the degree of acid suppression produced.

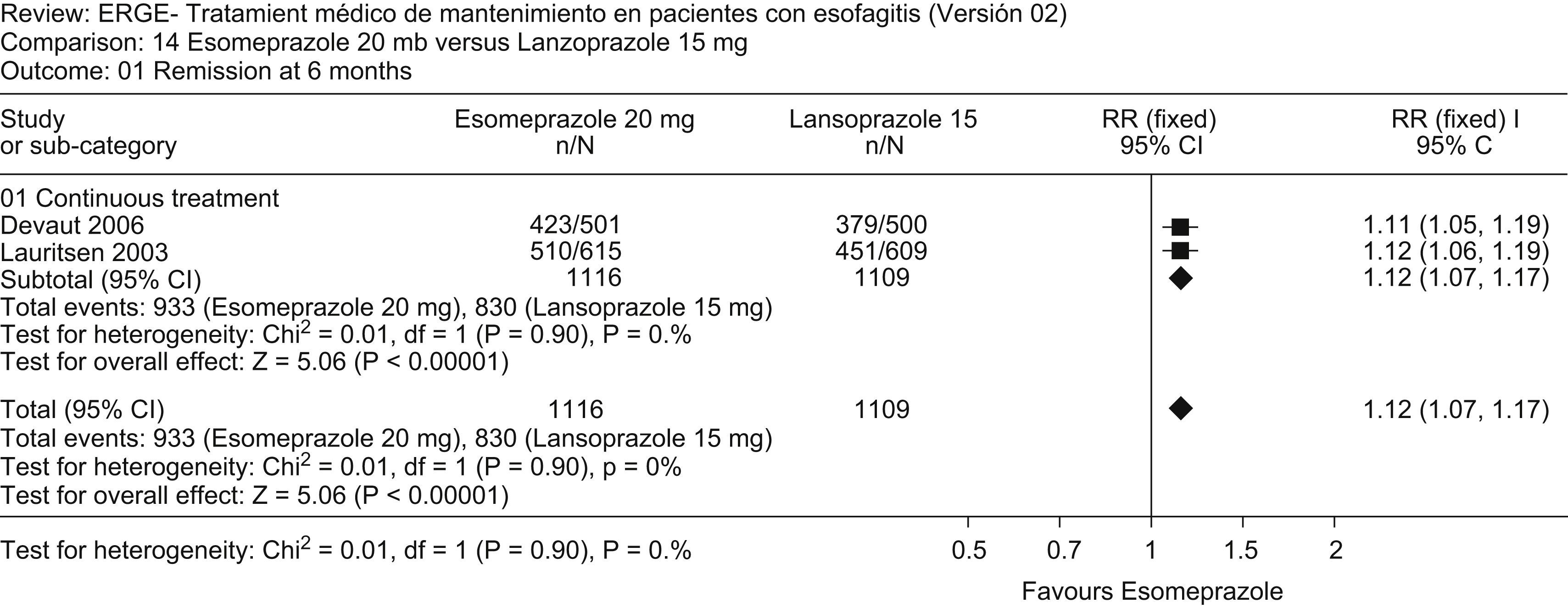

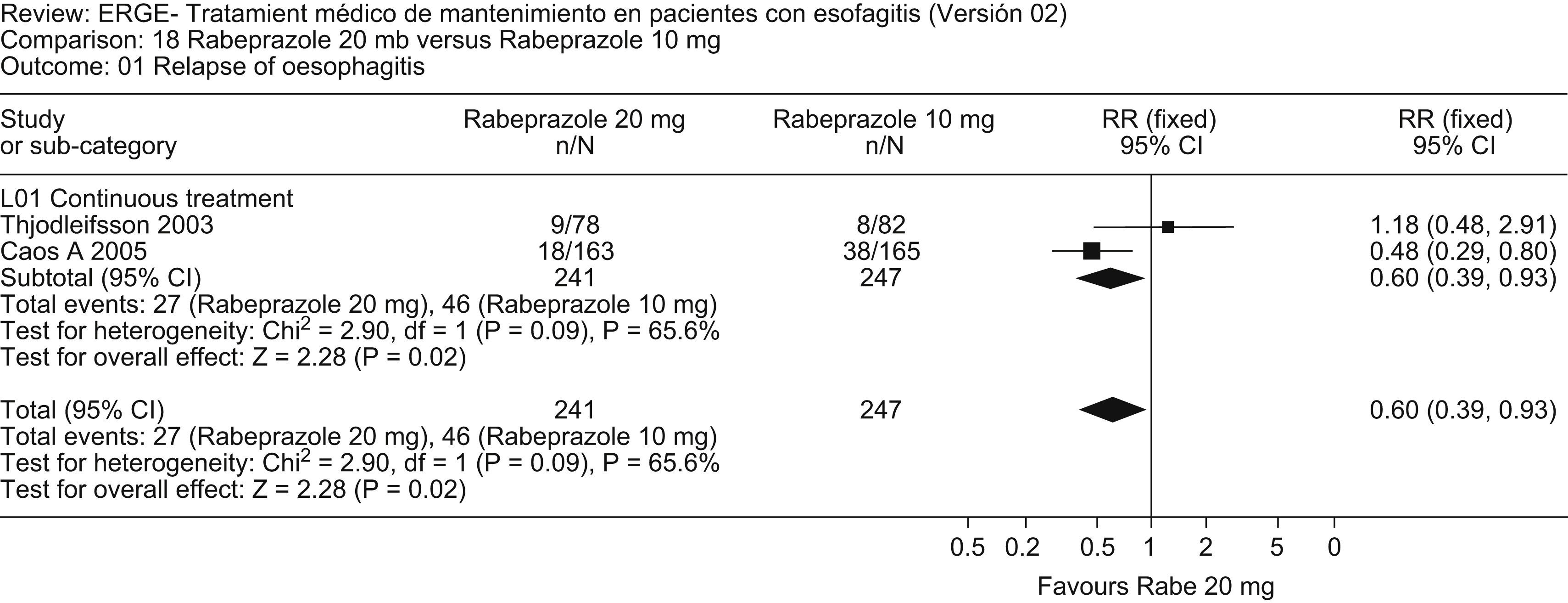

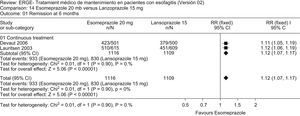

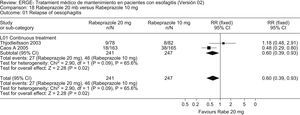

Review outcome: No relevant studies comparing PPIs with placebo for maintenance therapy in erosive esophagitis were published during the review period. However, a number of studies compared distinct PPIs. An updated meta-analysis that added the study by Devault52 to that of Lauritsen53 shows that esomeprazole 20mg is more effective than lansoprazole 15mg in maintaining endoscopic and clinical remission at 6 months (Fig. 4). Similarly, an updated meta-analysis that added the study by Caos54 to that by Thjodleifsson55 shows that rabeprazole 20mg daily is more effective than rabeprazole 10mg daily in preventing relapse of heartburn and erosions at 5 years (Fig. 5).

The EXPO study56 reported that esomeprazole is more effective than pantoprazole both in healing esophagitis after 4–8 weeks of treatment and in subsequently keeping patients in endoscopic and symptomatic remission at 6 months of maintenance therapy.

Impact on Recommendations: The new data do not affect the prior recommendation that continuous maintenance therapy with PPIs is superior to placebo, antacids and alginates, H2-RAs and prokinetics in preventing recurrent esophagitis and reflux symptoms. However, the updated meta-analyses do provide further support for the notion that the efficacy of PPI maintenance therapy is related to the degree of acid suppression produced by these drugs and that there is a dose-response relationship for PPIs in the long-term treatment of GERD.

Recommendation: There is good evidence supporting the use of PPIs instead of H2-RAs or prokinetics in the maintenance therapy of GERD patients (with or without erosive esophagitis) (grade A recommendation). Consequently, patients requiring continuous GERD therapy should be offered a PPI as first-line maintenance treatment. However, the data indicate that treatment outcomes are related to the degree of acid suppression achieved by PPI therapy; healing, and to a lesser extent, symptom resolution, are dependent upon the dose and frequency of PPI administration, as well as the choice of PPI. At lower doses, approved for maintenance therapy, esomeprazole is associated with lower relapse rates than lansoprazole or pantoprazole, especially in patients with more severe, LA grade C and ‘D’ esophagitis (grade A recommendation). For esomeprazole, as for other PPIs, dosage is also important; in this context, for example, rabeprazole 20mg daily is more effective than rabeprazole 10mg daily and esomeprazole 40mg daily is more effective than esomeprazole 10mg daily, although there is little difference between esomeprazole at 40mg and 20mg doses (grade A recommendation). Overall, full-dose PPI therapy is more effective than half-dose PPI therapy, although the clinical significance of these differences and of the differences between distinct PPIs remains unproven.

On-demand maintenance therapyi) Proton pump inhibitors

Overview: In patients with NERD, on-demand PPIs are more effective than placebo in controlling reflux symptoms such that patients are satisfied with their treatment.57,58 There is evidence of a dose-response effect for PPIs, at least at lower doses. However, although omeprazole 20mg was more effective than omeprazole 10mg as on-demand therapy, there was no significant difference in subsequent trials between esomeprazole 40mg and esomeprazole 20mg.59

Review outcome: An important study by Sjostedt60 comparing daily versus on-demand therapy with esomeprazole 20mg in 470 patients showed no differences between treatment strategies in symptom control or satisfaction with therapy but endoscopic remission at 6 months favored daily administration.

Impact on recommendations: There were no specific recommendations in the previous consensus publication, although the document recognized that, in NERD patients, on-demand PPI therapy was more effective than placebo in symptom control. Subsequent data support this conclusion with the caveat that on-demand therapy is less effective than continuous, daily therapy in preventing relapse of erosive esophagitis.

Recommendation: On-demand PPI therapy provides effective symptom control in patients with NERD and mild erosive esophagitis but is not recommended for the prevention of recurrent esophagitis.

Surgical therapyOverview: Antireflux surgery is similar in efficacy to pharmacological therapy (grade A recommendation) in individuals who respond to medical therapy; patients unresponsive to medical therapy are poor candidates for surgery. Open and laparoscopic antireflux techniques are similar with respect to GERD recurrence, the development of dysphagia and bloating and reoperation rates. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery is preferred because this modality is associated with reduced postoperative pain, analgesia requirements, inpatient hospitalization and impairment of ventilatory function, although the 2004 Consensus noted that persistent severe dysphagia is more common after laparoscopic surgery (1).

Review outcome: The comparison of surgical and medical antireflux therapies61–63 was supplemented by a new study (Mahon64) which compared laparoscopic Nissen fundoplications with PPI therapy and reported that surgery produced significantly better physiological control of acid reflux at 3 months, as well as significantly better gastrointestinal and general well-being in the laparoscopic Nissen fundoplications group at both 3 and 12 months. However, in this study, the medical treatment arm was based on the initial provision of half-dose maintenance PPI therapy and the mean daily dose remained less than the standard daily dose for each of the PPIs used. In summary, however, the four comparative studies reviewed evaluated different outcomes, making it inappropriate to aggregate the results in a meta-analysis.

The evaluation of open and laparoscopic antireflux surgery from the 2004 consensus was updated with data from three recent studies.65–67 Analysis of these studies with the nine previous studies indicated that the two approaches were not significantly different with regard to heartburn remission at 3 months. Open surgery was superior with respect to dysphagia at 3 months (RR 0.79; 95%CI 0.59–1.07), satisfaction with surgery (RR 0. 86; 95% CI 0.75–0.99) and dysphagia at 5 years (RR 0.18; 95% CI 0.04–0.78) whereas laparoscopic surgery was superior with respect to surgical wound infection, days of hospital stay, severe pain at 48h, respiratory and per-operative complications and wound pain.

Impact on recommendations: The more recent studies have not led to a change in recommendations and, overall, the results of the various studies do not show the consistency required to recommend antireflux surgery in preference to medical therapy or to recommend selection of one surgical approach rather than another.

Recommendation: The recommendation is unchanged with respect to the 2004 Consensus (see Table 2).

Treatment of Helicobacter pylori InfectionOverview: There are data to indicate that H. pylori infection is associated with changes in gastric acidity and acid secretion, that H. pylori-infected individuals with GERD may have more rapid healing and lower relapse rates for erosive esophagitis68 and that H. pylori eradication is associated with decreased PPI efficacy in reducing gastric acidity. However, there is also good evidence (type 1) that H. pylori infection has no effect on GERD and that its eradication does not worsen GERD symptoms.1,69

Review outcome: No relevant new data were identified during the review period.

Impact on recommendations: There are no changes to the recommendations with respect to the management of H. pylori-infected GERD patients.

Recommendation: The recommendation is unchanged with respect to the 2004 Consensus (see Table 2).

Endoscopic therapyOverview: The 2004 Consensus publication reported that there was no evidence from randomized controlled trials to assess the effectiveness of endoscopic treatment in comparison with medical or surgical therapy.

Review outcome: During the review period, three studies comparing endoscopic full-thickness plication (EndoCinch, Bard) with sham therapy were published, two in abstract form70,71 and one as a full, peer-reviewed manuscript72 . Although endoscopic therapy was associated with a reduction in heartburn frequency after 3 months in one study70 there were no other significant differences in symptomatic outcome in this or the other studies and the plication device is no longer available.

Impact on recommendations: There are no changes to the recommendations with respect to endoscopic therapy in GERD patients.

Recommendation: The recommendation is unchanged with respect to the 2004 Consensus (see Table 2).

Overall recommendationsThe measures below are recommended based on the 2004 Consensus, which has been modified, when appropriate, by new evidence that became available in the subsequent review period.

Behavioral approach: diet and lifestyleEncouraging overweight and obese patients with GERD to lose weight is reasonable, although the evidence base for this recommendation is debatable as there are no relevant randomized controlled trials on this topic. Other recommendations involving lifestyle and dietary changes should be decided on a case-by-case basis, in light of the professional's clinical experience (grade D recommendation).

Antacids, alginates and sucralfateThese three classes of drug may play a role in special situations, particularly in patients who experience adverse events in response to H2-RAs or PPIs or in those requiring transient symptomatic relief (grade D recommendation).

Pharmacological therapyShort therapyThere is good evidence supporting the use of PPIs instead of H2RAs or prokinetics for the initial management of mild erosive or NERD patients (grade A recommendation).

PPIs should be viewed as the initial therapy of choice (4–8 weeks). Currently, there is new evidence supporting the use of esomeprazole as the first choice rather than lansoprazole and omeprazole (recommendation A). However, the choice of PPI should also be based on local availability and costs (grade D recommendation).

H2RAs and prokinetics are considered good second line therapy (grade A recommendation).

Maintenance therapyThere is good evidence supporting the use of PPIs instead of H2RAs or prokinetics in the maintenance therapy of GERD patients (with or without erosive esophagitis) (grade A recommendation).

Consequently, patients requiring continuous therapy should be offered any PPI as their first line choice for maintenance, even though esomeprazole has been shown to be superior to lansoprazole at a maintenance dosage, especially in patients with esophagitis (grade A recommendation).

Regarding dosage, 40mg of esomeprazole is more beneficial than 10mg, but is almost the same as 20mg (grade A recommendation).

Daily administration of PPIs was superior to on-demand administration, while the latter seems to be more beneficial than intermittent administration.

Drug versus surgical therapyThe efficacy of surgery is comparable to that of drug therapy (grade A recommendation).

Surgical therapy: indicationsThe evidence reviewed showed that individuals who respond to medical therapy but are unable or reluctant to proceed with such therapy are good candidates for surgery (grade A recommendation). Patients unresponsive to pharmacological therapy are poor candidates for surgery.

Surgical therapy: open surgery versus laparoscopyThere is evidence favoring one approach or the other, depending on the outcomes measured; consequently, the choice will depend on the surgeon's experience and technical expertise, as well as each patient's decision (grade A recommendation).

Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infectionOnce the diagnosis of H. pylori is confirmed, the bacteria should to be eradicated by applying the appropriate therapy guidelines (grade D recommendation).

Endoscopic therapyEndoscopic therapy is still considered experimental. This modality is not recommended as standard routine practice, although it may be appropriate in clinical trials (grade D recommendation).

SummaryThere have been no major advances in the clinical management of GERD in the 3 years following the 2004 Latin American GERD Consensus. However, a number of points merit emphasis. Epidemiological studies increasingly show that obesity, now recognized as a major health problem in many countries, and lifestyle significantly contribute to the rising prevalence of GERD across the world. It therefore seems appropriate to endorse recommendations for weight loss by other health care organizations, despite the absence of randomized controlled trials demonstrating a reduction in GERD manifestations attributable to weight reduction.

The data on medical therapy indicate that PPI remain the mainstay of treatment for GERD in a very high proportion of patients. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have provided further evidence that the degree of acid suppression achieved by acid suppressant medication is a major determinant of outcome. The degree of acid suppression achieved depends on a number of factors, including PPI dose, the frequency of administration (e.g. on-demand, daily or multiple times daily) and the choice of PPI. At recommended doses, there are differences between PPIs in both acid suppression and clinical outcome but, ultimately, the choice of PPI also depends on availability, cost, physician judgement and patient preference.