This work aims to explore the status of gender diversity in corporate governance and its implications to corporate performance and emotional intelligence. With this purpose, the role of women in leading modern corporations and the pending gaps in equality were analyzed. Tourist corporations composed the sample of firms, due to its growing economic impact in a post-global financial crisis scenario. The study sample is comprised by the 118 companies listed at the STOXX® Global 3000 Travel & Leisure. Financial and corporate governance data provided by Reuters.com, were used for the period ending 2017. Additional data on corporate governance of each entity were gathered from official corporate website of each firm. We designed ad hoc indicators for gender diversity, along with differences in salary and seniority. Special attention was paid to the specific position held by women in each board, and its relationship to emotional intelligence, as a first step to a full research agenda. The results suggested very relevant gap in the three analyzed dimensions: presence, salary and seniority. Women tend to be focused only on several corporate tasks like those related to marketing and human resources management. This bias, which in a first view can be considered an additional manifestation of gender gap, is at the same time an opportunity to link modern corporations to a new style of management in which approaches like emotional intelligence could play a most prominent role. This research contributes in two different ways: (1) it demonstrate the enormous gap still existing between men and women at the top of tourist organizations worldwide and (2) it suggests several research pathways given the type of gender gap detected.

Companies, in particular listed corporations, face a strong requirement, even more in a post-crisis scenario, to be accountable for their performance. Shareholders are not the only public to inform. There exists a wide range of interest groups, such as customers, suppliers, employees, public agencies, among others, who do not simply intend to accomplish their traditional expectations, but they also wish to interact with companies that perform in an ethic and responsible way. Gender equality is a major issue in modern management, both public and private. There are two basic principles that complement each other: the first consist of social justice, which leads to providing women with the same opportunities as men in terms of access to jobs, including senior management, subsequently implementing actions of positive discrimination to solve disadvantages of the past. The second principle is the growing evidence in academic and business literature that when teams in general, and management boards in particular, are more diverse, also in terms of gender, firms experiment a significant business enhancement. Both realities can play the role of market signaling by the firms, in order to capture the attention of a growing crowd of more responsible investors, commercial allies, potential candidates for key job positions, etc. (Srivastava, McInish, Wood, & Capraro, 1997).

At the same time, new styles of management have arisen, in this environment in which all types of stakeholders show a growing consciousness with regards to environmental and social concerns. As outlined by Palmer, Walls, Burgess, and Stough, 2001, particularly in service-oriented firms, a key role of management is to motivate and effectively use interpersonal skills in order to favor better attitudes. According to these authors, Emotional Intelligence (EI) can play a significant role in selection process that concerns the management board.

Other authors have explored the relationship between emotional intelligence put in action in organizations and the gender variable. Mandell and Pherwani (2003) find significant differences between men and women managers when scoring emotional intelligence. If EI has to represent a growing force in modern management, gender diversity could be a compelling research topic.

The tourism sector has not been oblivious to this social and business change that has been in progress for several decades, increasingly incorporating both women and men into its staff, although the question remains as to what extent there still exist biases that impede women from fully incorporating to top management positions. Skalpe (2007) and Muñoz-Bullón (2009) explored salary gap in, respectively Norway and Spain, finding that industry as interesting to understand these phenomena, if more research is added to their evidences. With the purpose of exploring the interrelations between these concepts, the role of women in leading modern corporations and the pending gaps in equality is analyzed, and potential impact on performance is also scrutinized. Tourist corporations composed the sample of firms, due to its growing economic impact. This research aims then to contribute in two different ways: (1) it will explore the magnitude of potential gap still existing between men and women at the top of tourist organizations worldwide in a post-financial crisis scenario in which, according to Rekker, Benson, and Faff, 2014, the relationship between these key variables can have been modified and (2) it will suggest several research pathways given the type of gender gap detected and its relationship to these new forms of management. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the conceptual triangle of gender diversity, corporate performance and emotional intelligence, and identifies pending research questions. Section 3 describes the methodology of our study. Results are presented in Section 4 and, finally, Section 5 concludes.

2Gender diversity, corporate performance and emotional intelligence: conceptual triangleThe mechanisms to monitor the behavior of many companies, particularly those of larger size, and consequently their management bodies, have always been at the center of interest in diverse academic fields. As the behavior of these firms has concerned more diverse people and organizations, not only their shareholders, but also employees, customers and suppliers, competitors, public bodies, environmentalists and the media, business management has been gradually becoming more transparent and diverse, and this has had an effect on the structure and composition of the boards of directors and, subsequently, on their corporate management styles. Three different pathways can be open to explore how management boards evolve in this new corporate climate: (1) the link between gender diversity and the new styles and skills of management, connected to emotional intelligence (EI) and (2) the association between these factors and how they could allow the firms to obtain enhanced value or results.

Trying to explore first the link between emotional intelligence and gender, it is relevant to note that, since the popular writings of Goleman (1995), there exists a growing interest in evolving from simplistic views of intelligence based on academic skills to a more complex panorama of abilities. As surveyed by Mandell and Pherwani (2003), the Mayer-Salovey Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) (1999) measures four ability areas of emotional intelligence: perception, facilitation of thought, understanding, and management, going well beyond the traditional linguistic and logical-mathematical skills. These developments allowed the transition from traditional Intelligence quotients (IQ) to more comprehensive emotional ones (EQ and subsequent measurement instruments). Several studies have identified how women perform better in emotional intelligence measurements (Mandell & Pherwani, 2003; Mayer & Geher, 1996; Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 1999), and this first study identifies a link between emotion management and better performance. In fact, there are several studies from different conceptual perspectives that link EQ to business success of people and hence their organizations. Sometimes the abilities of top managers are labelled with a different name as social competence (Baron & Markman, 2003) and in other cases identifying EQ with specific abilities like leadership (Dulewicz & Higgs, 2003). These previous work tend to identify higher levels of EQ to success, for instance, when the tasks are organized in projects (Rezvani et al., 2016). So, as long as EQ can be linked to gender diversity, the study of gender in corporate governance become an even more central topic for further research, having in mind that these authors used multi-sector samples and interviews to management officers as research method, which is an invitation to provide to this field from a different methodological perspective. Recently, other authors have suggested the superiority of women over men in these emotional abilities, like Cabello, Sorrel, Fernández-Pinto, Extremera, and Fernández-Berrocal (2016) and Mohanty and Das (2017).

In fact, this and other key aspects of corporate governance have been scholarly studied in deep, practically since there are legal developments in this regard. It should be noted, at the international level, the efforts made by different authors to relate the characteristics of corporate governance with the crisis of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression of the 1930s. Recent works still analyze the impact of corporate governance on results or value of firms (Shawtari, Salem, Hussain, Alaeddin, & Thabit, 2016). In this respect, it is worth noting the work of Clarke (2004), as well as that of Grant (2003), both of which stress the fact that it is possible to draw a parallel line between economic cycles and corporate governance styles.

These styles are heavily dependent on how management boards are composed. As in other areas, the presence of women in corporate governance has been growing over time. But this fact is seen by some authors not only as the recovery of a place unjustly unemployed, but as a factor that can positively influence business management, while there seems to be that evidence that an increase in human diversity of management teams has a positive impact on the result or the financial position of the corporations. The work of Bass (1997) suggested that those leaders with higher emotional quotients (more likely, women) could reach better financial performances and be rated higher by subordinates. The link between gender and enhanced financial results has also been confirmed in several context by recent contributions like the work of Catalyst (2011); Kakabadse et al. (2015), and Opstrup and Villadsen (2015), in terms of gender acting as a force on value or results, even taking into account that gender equality does not work alone but with additional factors. Tejedo-Romero, Rodrigues, and Craig, 2017 explores how gender diversity impacts the level of corporate transparency precisely related to human resources management in Spanish corporation. For that reason, in this study, several variables traditionally connected to corporate transparency are included as potential explanatory factors. This paper contributes to this empirical effort with an internationally diverse sample of tourist corporations.

Given the surveyed literature, it is still a matter of research to what extent emotional intelligence and gender have an impact in concrete industries and their achievements. Specially after the findings of Pletzer, Nikolova, Kedzior, and Voelpel, 2015, in the sense that the mere representation of females on corporate boards could not be related to firm financial performance if other factors are not considered. In this work, the specific case of leading global tourist corporation is explored, as long as, according to Palmer et al. (2001), these connections can take place more intensively particularly in service-oriented firms, along with the fact that previous empirical work was performed before the financial crisis. In line with the work of Carter, Simkins, and Simpson (2003); Francoeur, Labelle, and Sinclair-Desgagne (2008) and Erhardt, Werbel, and Shrader (2003), we will try to examine not only what the situation is in terms of equality, but also whether greater gender diversity at the top of the organization is leading to better results or a significantly different financial behavior. With this purpose a specific set of metrics is prepared, in order to conduct the subsequent empirical work.

3MethodologyThe good performance of tourism companies internationally also puts them at the center of social focus and scholarly interest with greater intensity, along with respect to their level of gender equality. Hence, this study sample is comprised by the 118 companies listed at the STOXX® Global 3000 Travel & Leisure. Financial and corporate governance data provided by Reuters.com, were used for the period ending 2017. Additional data on corporate governance of each entity were gathered from official corporate website of each firm. This sample of companies can be considered as a useful sample in the sense that, being the leading companies in the global tourism arena, they attract many other firms in business practices and can be regarded as the vanguard of the industry. The composition of the index is dynamic and according to the procedures of STOXX Corporation, and fully detailed in their website. These data sources are also used traditionally in academic environments due to the standardization in the information provided, in particular, when measuring corporate transparency (Band & Gerafi, 2013; Bonsón & Flores, 2011). In particular, for the specific case of corporate governance data, even due to data availability from the source reporting corporation, or due to technical or legal obstacles, not all relevant information is provided. I.e., not all salary and compensation is disclosed for all women and men present in a given board. As illustration of that, for the first company in the sample by alphabetic order (Accor), compensation data is provided for 8 out of 32 members in the top management board (https://reut.rs/2GBHPKh). In the other hand, Reuters is as relevant as data source that even services like Google Finance point to this source.

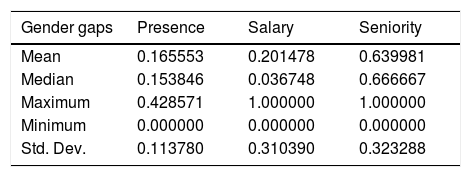

We designed ad hoc indicators for gender diversity, along with differences in salary and seniority. Special attention was paid to the specific position held by women in each board, and its relationship to emotional intelligence. Table 1 offers a complete view of the variables involved in the study, in particular of the three metrics proposed to properly capture any potential gap in gender diversity of these corporations:

- ●

Presence: proportion of women on the board of directors.

- ●

Salary (equality): proportion of the maximum salary received by women over the maximum salary received by the highest paid member of the board.

- ●

Seniority (equality): seniority (years at current position) of the most experienced female member compared to the most experienced member of the board.

- ●

Design of variables to measure gender gaps.

| Base variables | Calculation | Sense | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence gap | |||

| Number of women over total board size | Presence of women at Management Boards | y1 | |

| Salary gap | |||

| Salary of woman (highest) over total absolute salary (highest) | Salary gap between highest compensation to female member and the corresponding maximum compensation | y2 | |

| Seniority gap | |||

| Years in current position of woman (highest) over years in current position (absolute highest) | Seniority of the most experienced female member compared to the most experienced member of the board. | y3 | |

The preparation of these metrics are not so disruptive taking into account previous measurements of gender gap, like those used by Boulouta (2013) for an almost identical metric for our presence and Rekker et al. (2014) with a similar indicator to our salary one. The calibration of these metrics resides to our desire of promoting subsequent research work in with the data collection could be easily replicable from a unique source. On the other hand, current research in gender issues clearly requires more complex indicators, like in Bastida (2018). For the specific case of seniority, its inclusion in this study is justified due to the interest in how this variable is related to salary and how they evolve in modern organizations, where the environment becomes more competitive and promotion and payments are no longer related to seniority but to other metrics like productivity (Magoshi & Chang, 2009).

The other variables are those related to the country and sector of each firm, along with financial performance and size, measured by means of net income and revenue for the last year available (Table 2). These variables have been extensively used in works that analyzed corporate transparency (most of them surveyed by Bonsón Ponte & Escobar Rodríguez, 2002; Gandía, 2003). In a majority of these works, the hypotheses are formulated in a similar manner: the bigger and/or more profitable the firm, the higher is the public scrutiny on its activities and the most the transparency and ethics it tends to exhibit. Salary and seniority information is used, obviously, when it is available at the source (i.e., if there are better-paid members in a given board but, for legal or technical reason the data is not disclosed at the reuters.com profile, this data cannot be computed, obviously). Descriptive statistics and ordinary least squares regressions will be shown in the results section. Ordinary least squared are selected as initial tool due to the exploratory nature of the present study. Global significance of the selected models (F-statistics), individual significance of explanatory variables (t-statistics) and the usual assumptions like normality in the resulting residuals were obtained. OLS (Ordinary Least Squared) is a common technique in research of this kind as in Bear, Rahman, and Post (2010).

Potential explanatory variables.

| Base variables | Details | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Country | 18 countries composed the sample of firms from STOXX 3000 Travel and Leisure | x1 |

| Sector | 5 main activities are present in the sample of firms: Intermediation, Transport, Cruises, Accommodation and Other/Leisure | x2 |

| Size | Measured by means of, respectively, the total revenue for the fiscal year 2017 and the corresponding net income. | x3, x4 |

This section provides an overview of the relationship detected and the best regression models that have been possible to implement with the available data. In the first place, Table 3 outlines the situation for the three types of gap explored. According to that, the presence of women on the boards of directors is still scarce, in particular, it is less than 17% on average, with standard deviation of around 11%. The range for the corresponding levels of salary and seniority gaps are respectively 20% (deviation 31%) and almost 64% (deviation 32%). These first impressions have to be considered carefully in the case of salary, because not all woman members of the boards had this particular data available in all cases, but presence and seniority was always available, so, the situation in general is of a significant gap in all three dimensions.

Regarding the salary difference, it is very remarkable. The higher salaries of women represent only a symbolic fraction of what is perceived by the best paid person, who in all cases is a man. Of course, this difference can be explained in terms of the responsibilities that women reach in their ascending careers, as the metric is designed to capture the difference between best salary paid to women with the absolute best (usually the CEO or similar), but another perspective for this apparent bias is that this metric can be regarded as a quantitative indicator of how far are women from these top positions. Regarding the seniority of the position, women again come out unfavorably from this analysis, presenting less experience that is, having recently joined their peers at the board. Additionally, the three types of equality/inequality seem to be related, so that companies that have later incorporated women into their boards of directors maintain greater wage inequality, and have less women in top positions (Fig. 1).

Regarding the relationship between the gender variables studied and the other corporate variables collected, it is interesting to analyze substantial differences among countries in the sample (Table 4), with lower inequality in presence for Australia, France, and Germany, (more than 25% of presence).

When analyzing differences related to the sub-sector of activity, the results of Table 5 show that Accommodation is the activity in which firms retain more presence of women in their management boards (almost 25%) compared to Transport (12%).

Additional comparisons were implemented, in particular with two financial variables that act as `proxies´ of company size: revenue and net income. Fig. 2 presents the comparison of the three types of inequality with respect to size in both cases, finding a negative relationship, that is, those firms with higher financial figures tend to be less diverse in their boards, presenting more inequality in the three dimensions considered. This negative relationship is subsequently explored by means of ordinary least squares in Table 6. The relationship is not very strong (in terms of R2), but significant at 5% in the case of seniority, and at 1% in presence. This result is notably interesting, as it apparently contradicts the relationship between public scrutiny (over bigger or more profitable corporations) and gender diversity, and the mediating role that financial performance and size could have been playing. (Bear et al., 2010, Larkin, Bernardi, & Bosco, 2012). The great heterogeneity among tourist corporations can be a potential cause for the sense of this empirical relationship. This will require further research and inter-sectorial comparisons.

This is also convenient to put our empirical findings in relation to the surveyed literature. In particular, Cabello et al. (2016) were able to detect greater levels of EI and related abilities among women in all age ranges but other authors, like Mandell and Pherwani (2003) did not find a significant link between gender and transformation leadership style in organizations. Additionally, there are mixed views in previous results regarding the role of EI on gender adaptation to college studies, a key to top management positions. Taking into account the higher women qualifications level (Tejedo-Romero et al., 2017) in the particular context of Spain, it is worth noting that “tourism male workers earn on average 6.7% higher monthly wages than their socially comparable female counterparts” (Muñoz-Bullón, 2009: 647), a similar situation to that detected at the Norwegian tourism industry (Skalpe, 2007). So, in some sense, our study is confirmatory in terms of salary gap, but on the other hand it adds additional empirical evidence in order to continue the debate on how EI impacts performance.

In order to complete the quantitative work, an additional exploratory analysis has been implemented, with respect to the details of each top position occupied by women at these management boards. The position of the women that exhibit better salary is registered. Table 7 consists of an excerpt of the most relevant of these positions in the sample. This list of positions reveals that women tend to be engaged in Human Resources management, and secondly, as Vice-president, Vice-`chairman´ or similar auxiliary tasks or in activities related to Marketing and Communication roles. This evidence can be interpreted in a two different way. The first, as an additional manifestation of gap, as long as it is possible to find women at the top level in universities in other key areas, like Finance, Accounting, Operations, etc. But, the second view is complementary: being precisely focused in these activities and even being so poorly represented at the governing bodies of the corporations, the nature of the activities involved could allow them to have a more significant impact in the management styles like those discussed here. However, it was not possible in this article to complete this third dimension of the conceptual triangle (gender, performance, EQ) in a satisfactory and conclusive way, task that will require future research work.

Excerpt of position name of women with highest compensation at corporate management boards.

| Firm | Position |

|---|---|

| ARAMARK | Executive Vice President – Human Resources |

| ARISTOCRAT LEISURE | Chief Financial Officer, Company Secretary |

| CHEESECACKE FACTORY | Executive Vice President, Secretary and General Counsel |

| CHOICE HOTELS INTL | Senior Vice President, General Counsel, Corporate Secretary |

| COMFORTDELGRO CORP LTD | Group Human Resource Officer |

| CROWN RESORTS | Joint Company Secretary |

| DELTA AIR | Chief Human Resource Officer, Executive Vice President |

| DOMINO'S PIZZA | Executive Vice President, Chief People Officer |

| GENTING BHD | Company Secretary |

| GENTING MALAYSIA | Corporate Secretary |

| HYATT HOTELS | Executive Vice President, Chief Human Resources |

| IAG | Chief of Staff |

| IMAX | Executive Vice President, Human Resources |

| JAPAN AIRLINES | Senior Managing Executive Officer, Chief Director of Communication, Representative Director |

| LUFTHANSA | Deputy Chairwoman of the Supervisory Board and Employee Representative |

| MADISON SQARE GARDEN | Executive Vice President |

| McDONALD'S | Executive Vice President, Global Chief Marketing Officer |

| MTR CORPORATION | Human Resources Director |

| PANERA BREAD | Senior Vice President, Chief People Officer |

| SPIRIT AIRLINES | Vice President and Chief Human Resources |

| THOMAS COOK | Group General Counsel, Company Secretary |

| WYNN RESORTS | Executive Vice President, General Counsel, Secretary |

| YUM! BRANDS INC | Chief Transformation and People Officer |

Companies are under increasing pressure from the environment, regulators, interest groups and public opinion to be increasingly transparent and more ethical. The purpose of this work has been fundamentally to provide a first approach to the situation of gender equality in the boards of directors of the global tourism industry in a post financial-crisis scenario. There have been revealed different significant relationships that will serve for further studies, once the empirical effort that has led to the present exploratory work has been completed. Additional research will be required to address a greater number of possible causes, as well as to perform comparisons with other non-tourism sectors on an international scale, and longitudinal analysis. These results should be treated with caution considering the exploratory nature of this work and taking into account the specific design of the metrics involved and the sources of data. Additional research will be required in order to assess the impact of women in these particular roles and their impact on results. Limitations of this study, including the features of the data sources, will be overcome in subsequent research works.

This study shows that it still exist a very relevant gap in the three analyzed dimensions of gender gap: presence, salary and seniority. When analyzing in detail in which top positions is possible to find women, it appears that they tend to be focused primarily on several corporate tasks like those related to human resources management, along with auxiliary roles and those related to marketing. This bias, which in a first view can be considered an additional manifestation of gender gap, is at the same time an opportunity to link modern corporations to a new style of management in which approaches like emotional intelligence could play a most prominent role. In order to empirically complete the proposed conceptual triangle and to further investigate the mediating role of emotional intelligence in the connection between gender diversity and corporate transparency and behavior, subsequent research will be required.

Almudena Barrientos-Báez is Associate Professor at Iriarte University School of Tourism adscribed to the University of La Laguna (Spain). She holds a Master's degree in Tourism Management and a Master in Event Management. Her main research interests are Emotional Intelligence, emotion management, professional performance in the Tourism industry. She has published several books (Mc Graw-Hill) on ICT applied to teaching activities, University innovation, digitization 2.0 and content excellence. She has also attended several relevant conferences on Applied Emotional Intelligence, relationship between Emotional Intelligence and the professional future of Tourism managers. She is a member of the research team at Iriarte and a PhD candidate at the Camilo José Cela University in Madrid.

Alberto Javier Báez-García is a Lecturer in Polítical Science and Administration at the Uniersity of La Laguna. He is Ph.D. of Political Science. His main research field are tourism policy, political parties, elections and electoral campaigns. He has published several articles about these topics and some books about political parties and elections in the Canary Islands.

Francisco Flores-Muñoz is an Associate Professor of Business and Economics at the University of La Laguna (Spain). His main research interests are IT acceptance, digital reporting and transparency and social media. He has published international articles in various journals, such as Government Information Quarterly, The International Journal of Digital Accounting Research, Online Information Review, Financial Markets, Institutions and Instruments, International Journal of Metadata, Semantics and Ontologies, International Journal of Networking and Virtual Organizations and Online Magazine. He has also published books and other publications. He is member of the Commission on New Technologies in Accounting of the Spanish Accounting Association.

Josue Gutiérrez-Barroso is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of La Laguna (Spain). His main research fields are education, tourism and methodology. He has published articles, books and other publications about these topics in the last ten years. Currently, he is the President of the Official Association of Political Science and Sociology of Canary Islands.