This study examines whether the level of product involvement influences how emotions drive consumer satisfaction. Based on the Theory of the Hedonic Asymmetry we analyze through Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) how emotions drive consumer satisfaction. A sample of 570 respondents was gathered for a high involvement product – wine –, while a sample of 431 consumers was collected for a low involvement product – a cup of coffee –. Results show that positive emotions exert a higher influence on satisfaction in low involvement products, rather than in high involvement products, suggesting that situational factors – such as the occasion of consumption – could be acting as qualifiers of pleasant emotions. Additionally, our findings support the moderating role of product involvement on the consumption-elicited emotions and satisfaction link.

Individuals are constantly consuming products in their everyday lives and experiencing emotions related to what they consume. Research on emotions and consumer behavior has appeared in marketing literature with an increasing importance, focusing on different aspects such as the emotions evoked by different products (Dube, Cervellon, & Han, 2003), the influence of emotions in consumer satisfaction (Phillips & Baumgartner, 2002), or even the influence of the emotional state on consumer loyalty and purchase intention (Wood & Moreau, 2006). Similarly, the research on emotional processes and satisfaction has deserved great attention, and the concept of involvement with a specific product category may be a useful explanatory element.

Previous research reports that high involvement products are those for which consumers invest time and effort to make the purchase decision (Bell & Marshall, 2003); being often expensive products that entail higher levels of purchase risk (Mittal, 1989). Conversely, low involvement products are cheap goods commonly consumed in a routine decision making, with minimal information search and low purchase risk (Bell & Marshall, 2003; Mittal, 1989). Interestingly, products that are the most satisfying in a traditional perspective are frequently the least involving (Richins & Bloch, 1988). For example, a radio that works reliably for years meeting all the expectations will rarely command any interest from the owner. However, there is little research on the relationships between consumption-elicited emotions and the level of product involvement.

This study focuses on the emotional state elicited by product consumption and the relationships with the level product involvement. The concept of involvement has been defined as being a characteristic of either a product or of an individual (Laaksonen, 1994). More precisely, we focus on product involvement, meaning that the nature of the product itself plays an important role in determining involvement. Finally, we have considered the Theory of Hedonic Asymmetry that suggests that individuals respond to products with primarily positive emotions (Desmet & Schifferstein, 2008). The present study addresses two main objectives. The first objective is to examine whether the level of product involvement influences how consumption-elicited emotions drive satisfaction. The second objective is to determine whether pleasant emotions prevail when consuming high involvement products. So, the underlying premise is that consumption elicited emotions may have a different impact on consumer satisfaction with the product, but this impact would be moderated by the level of product involvement. The present paper is structured as follows. First, a review of the literature on consumer emotions is developed. Then, the research hypotheses are presented. Next, we describe the methodology, followed by the results. Finally, we discuss the managerial implications and research limitations, suggesting guidelines for future research.

2Literature review2.1Emotions in consumer behaviorEmotions are commonly considered as “a multi-component phenomenon with a multi-component response, consisting of a set of behavioral, physiological and expressive reactions and subjective feelings” (Mehrabian & Russell, 1974). Later, Scherer (1982) conceptualized emotions as “an episode of interrelated changes in the states of all or most of the organismic subsystems to the evaluation of a stimulus”. Similarly, other authors have defined emotions as “a brief, intense physiological and mental reaction focused on a referent” (Izard, 1977), or as “a complex set of interactions among subjective and objective factors, giving rise to affective experiences” (Dube & Menon, 2000). The marketing literature assumes that emotions can be elicited by a product or a brand. Thus, we can refer to consumption emotions as “the set of emotional responses elicited during product consumption experiences” (Westbrook & Oliver, 1991).

Previous research on the influence of emotions in consumer behavior has focused on different aspects: the identification of emotions arising in consumption situations (Richins, McKeage, & Najjar, 1992), the emotions evoked by different products (Dube et al., 2003) or services (Dunning, O’Cass, & Pecotich, 2004); the examination of how emotions lead to different consumption behaviors (Lerner, Small, & Loewenstein, 2004; Macht, 2008); the influence of emotions on product attitudes (Dube & Menon, 2000), consumer satisfaction (Phillips & Baumgartner, 2002), loyalty and purchase intention (Wood & Moreau, 2006). More recent studies have also examined the relationships between the products’ sensory characteristics and the individual emotional response (King & Meiselman, 2010).

The consumption context, situation or setting refers to those elements involved in the act of consumption that are external to the individual and go beyond the specific product being consumed. Authors like Richins (1997) highlighted the importance of the context in which the consumption takes place, suggesting that emotions are context specific (Richins, 1997), and that the consumption context influences the emotional experience elicited by product consumption (Ferrarini et al., 2010). The concept of the context of consumption comprises three aspects (Barrett et al., 2007; Ferrarini et al., 2010). First, the consumption setting, such as the place where the product is usually consumed or the location of the consumption, such as at home, at work or at a restaurant (Marshall & Bell, 2004). Second, the habits of consumption, meaning that some products are consumed on particular occasions. For example, some food products are typically consumed at appropriate meal times, being considered as “meals” or rather as “snacks” (Birch, Billman, & Richard, 1984). Finally, the cultural meaning of products, representing cultural, geographical or historical differences in product consumption. Therefore, emotions not only represent the evaluation of a stimulus, but also the assessment of the occasion and situational circumstances in which the emotion is experienced (Barrett et al., 2007).

2.2The influence of emotions in consumer satisfactionThe distinction between positive and negative emotions seems to be a basic emotional experience; and consequently pleasantness is one of the major dimensions of the emotional experience (Laros & Steenkamp, 2005; Russell & Mehrabian, 1977). Accordingly, emotions can be classified according to the pleasant–unpleasant dimension (Diener, 1999), and individuals find it easy to classify emotions in terms of positive and negative valence (Schifferstein & Desmet, 2010).

Frijda (1986) proposed an asymmetrical adaptation of individuals to pleasure and pain that was named as the Theory of Hedonic Asymmetry, meaning that pleasure fades while displeasure persists. Then, the literature has focused mainly on negative emotions experienced by individuals. However, regarding the emotions elicited by food products, Desmet and Schifferstein (2008) showed that food products evoke a wide range of emotional responses that tend to be mainly positive. In other words, pleasant emotions are more relevant and most strongly experienced than unpleasant emotions.

This asymmetry for emotional responses to food products was confirmed for different product categories (Ferrarini et al., 2010; King & Meiselman, 2010; Schifferstein & Desmet, 2010), extending the Theory of the Hedonic Asymmetry. According to this theory, food products are likely to elicit more positive than negative emotions and consumers have a predominantly positive affective disposition toward products. All recent research on consumption-elicited emotions emphasizes the positive nature of the emotions associated with products; highlighting that individuals primarily respond to consumer goods with positive emotions (Schifferstein & Desmet, 2010).

Emotions are one of the core components of the consumer satisfaction construct (Barsky & Nash, 2002). Prior studies have conceptualized consumer satisfaction as either a cognitive response (Bolton & Drew, 1991), as an affective response (Halstead, Hartman, & Schmidt, 1994), as a psychological state (Howard & Sheth, 1969), as an overall evaluative judgment (Westbrook, 1987) or as an evaluation process (Johnson & Fornell, 1991). Similarly, Oliver (1997) conceptualized satisfaction as a fulfillment response, understood as “the consumer judgment of the product or service feature, or a judgment on the product or service itself, provided a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfillment”.

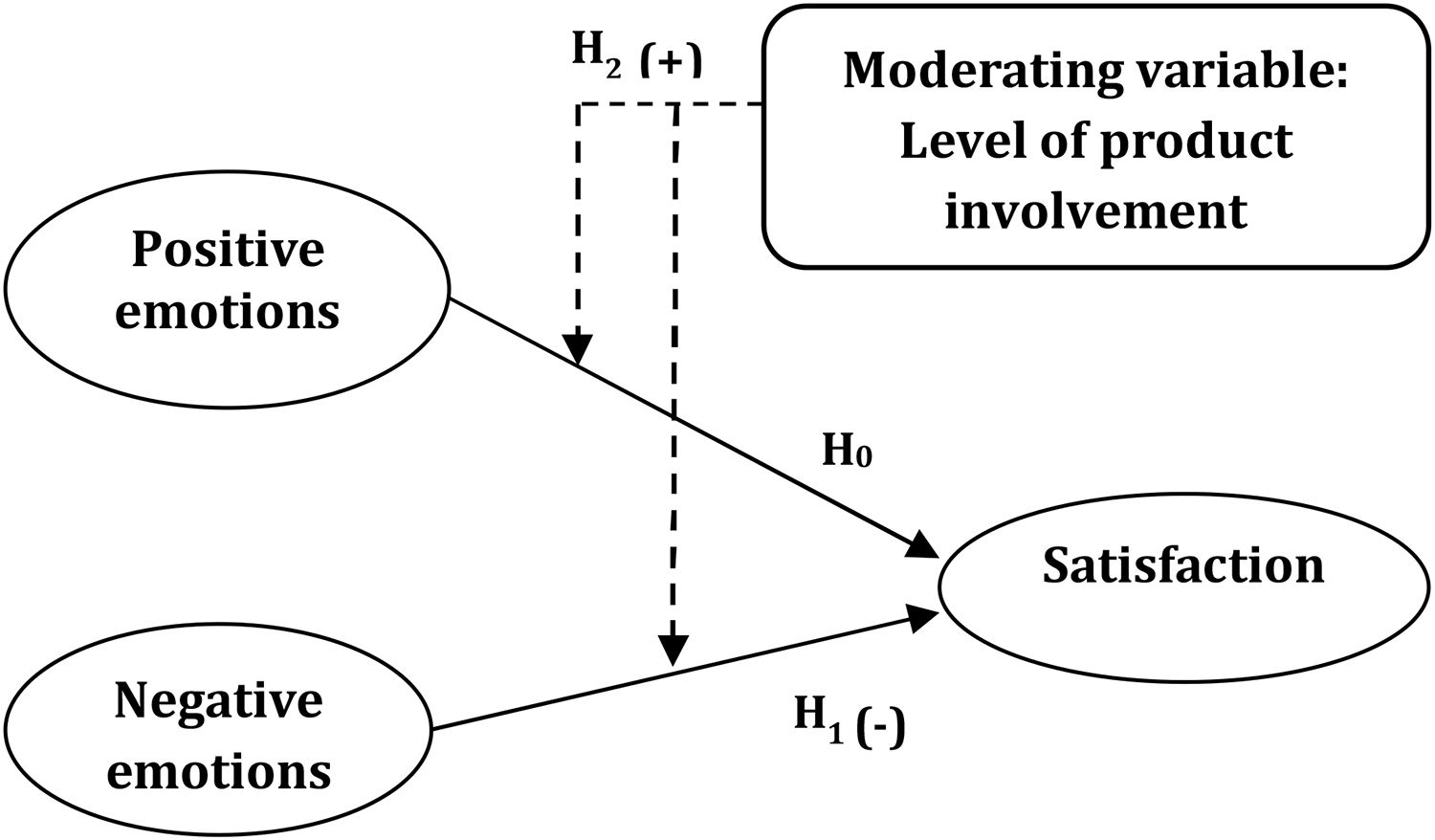

The seminal work of Westbrook (1987) showed that the relationship between consumption emotions and satisfaction could be characterized by dimensions of positive and negative affect; influencing satisfaction judgments. Accordingly, a great body of literature suggests that positive and negative emotions play an important role in influencing consumer satisfaction (Richins, 1997). More specifically, pleasant emotions positively correlate with satisfaction (Bloemer & DeRuyter, 1999); while being negatively correlated with negative affect (Mano & Oliver, 1993). Consequently, we propose that positive/pleasant consumption would positively influence consumer satisfaction. Therefore, we present the following hypothesis:H0

Positive emotions have a positive (or direct) influence on consumer satisfaction.

Conversely, when emotions are negative, the individual evaluations are likely to be negative (Clore, 1992). So, we propose that negative emotions will negatively influence consumer satisfaction:H1

Negative emotions have a negative (or inverse) influence on consumer satisfaction.

2.3The concept of involvementThere is not a general consensus in the theoretical construct of involvement. According to Zaichkowsky (1986) there are three types of consumer involvement: with products, with purchase decisions and with advertisements. Further, Zaichkowsky (1986) highlights the three main antecedents influencing consumer involvement, namely personal factors – such as needs, interests and values –, stimulus factors – such as the differentiation of alternatives –, and situational factors – like the purchase or consumption occasion –. Likewise, consumer involvement may drive to some consequences like the importance of the product category to the individual, the amount of information search or the time spent in evaluating alternatives (Zaichkowsky, 1986) or the perception of the sensory properties of products (Marshall & Bell, 2004).

Much of the involvement definitional concern relates to whether involvement is object or subject-oriented (Beatty, Kahle, & Homer, 1988). Authors like Bloch (1982) note that involvement refers to “an internal state reflecting the amount of interest or attention a consumer directs toward a product, referring to it as product involvement”. Likewise, Beatty et al. (1988) describe the ongoing concern for a product category as ego involvement, conceptualized as the importance of the product to the individual and to the individual's values and self-concept; being different from the purchase involvement, related to the concern or interest when purchasing the product. Then, product involvement could be defined as “the feelings of interest, excitement, motivation and enthusiasm that consumers have about a specific product category; thus being product specific” (Marshall & Bell, 2004). Consequently, the level of involvement could be classified based on the degree of effort that consumers devote to the product and to the time invested in the choice decision and the financial and social risk of the purchase itself (Bell & Marshall, 2003).

Other authors have proposed that the involvement construct could be classified into enduring, situational and response involvement (Lesschaeve & Bruwer, 2010). According to Ogbeide and Bruwer (2013) the enduring involvement is related to the general personal relevance or interest of a product category to the individual; while situational involvement is transitory and influenced by changes in the consumer's environment. Prior research shows that both product involvement and the consumption situation significantly influence consumer behavior and the importance allocated to product attributes (Quester & Smart, 1998). In the present study we will consider the involvement with products, referring to it as product involvement.

2.4The levels of product involvementPrior literature examines the involvement in terms of level – high versus low –, since the level of involvement ranges from low to high and varies across products, individuals and situations (Bell & Marshall, 2003). Mittal (1989) indicates that the level of involvement relates to the individual needs and motives within a choice or purchasing context, highlighting the importance of the environmental or situational factors. Therefore, consumers exhibit different levels of involvement for different products, and some product categories are generally perceived to be more involving than others (Bell & Marshall, 2003). Accordingly, consumers with high product involvement have greater interest in product information, compare product attributes, hold more favorable beliefs about the product features and show higher purchase intention (Zaichkowsky, 1985). Similarly, the high involvement products are those for which the consumer invests time and effort to make the purchase decision (Bell & Marshall, 2003). Conversely, low involvement products are those for which the individual does not consider the choice decision to be important and the search for information about the product is minimal (Bell & Marshall, 2003).

2.5The moderating role of the level of product involvementAccording to Schifferstein & Desmet (2010), there are three main product related appraisals. First, the aspiration-based products facilitate the consumer goals’ achievement; second, the pleasure-based products provide pleasure-; and finally, the integrity-based products should meet or exceed the consumer expectations. However, these three product-based appraisals may vary according to the level of product involvement. More precisely, in low involvement products the aspiration-based appraisal and the integrity-based appraisal could be low. For example, the consumption of a bag of potato chips may not facilitate consumer goals and may not even meet the consumer expectations, but the consumer may be just seeking for pleasure. Nevertheless, in the purchase of high involvement products, the appraisal of the three elements could be determining the consumption process. So, the emotions that are experienced in a consumption situation may depend on the three product-based appraisals, which could vary substantially depending on the level of product involvement.

Richins and Bloch (1988) show that consumer's involvement with products is one possible influence on satisfaction. Consumers should be more involved with products linked with positive affect that generates pleasant emotions, rather than unpleasant emotions (Baumgartner, Sujan, & Bettman, 1992). In this vein, some authors posit that the hedonic value of the product influences involvement. So, the rewards inherent to the product pleasure value provide consumers with strong reasons to be involved with a product (Jain & Sharma, 2000). On the other hand, Mano and Oliver (1993) reported that high involvement products could elicit both positive and negative emotions. They show that involvement enhances all the affective experiences, and that high involvement products elicit stronger emotional reactions, both including positive and negative affect. Hence, we propose that the level of product involvement would influence consumer satisfaction (Fig. 1); and that that high involvement products would elicit higher positive emotions, than low involvement products. So we present the following hypotheses:H21

Product involvement moderates the relationship between positive emotions and satisfaction.

H22Product involvement moderates the relationship between negative emotions and satisfaction.

3Methodology3.1The selection of product categoriesWe selected two different products in order to conduct the research: wine was selected as a high involvement product and a “cup of coffee” as a low involvement product. The reason for the product category selection was based on several criteria (Table 1). In the first place, we considered the consumption occasion for selecting the products, since the consumers were asked about their emotions when drinking wine in a restaurant in a “dining-out-of-home” context and when drinking a “cup of coffee” in a collective canteen at the workplace during a lunch break. Secondly, the price of the product was considered, being the price of a bottle of wine in a restaurant much more expensive that a “cup of coffee” in a canteen; since the price of a “cup of coffee” is cheap, being commonly one euro. In fact, according to Mittal (1989) the consumption of wine at a restaurant could be considered a high involvement product since it is costly and sometimes more expensive than the food. The third criteria is the decision making effort, given that the selection of a bottle of wine at a restaurant may entail some consumer effort; while the selection of simple “cup of coffee” at a workplace canteen does not seem to entail decision effort, since it is one of the most highly occurring consumption situations. In fourth place, we considered the importance given to the product brand, since consumers perceive differences among brands in high involvement products (Mittal, 1989). In this vein, wine could be considered a high involvement product, since consumers perceive inter-brand differences (Mittal, 1989), but when asking for a “cup of coffee” at the workplace, consumers do not select a specific coffee brand. Likewise, we considered the purchase risk as a variable influencing the product involvement (Mittal, 1989), since consumers are likely to feel involved about the product if they perceive the purchase to be risky. Finally, the social risk was considered, given that the type of product selected may have a social value (Bell & Marshall, 2003). Accordingly, the consumption of wine at the restaurant entails a social risk, given that the bottle of wine is often shared with others; but drinking a cup of coffee in the workplace does not entail social risks.

We selected two different products in order to conduct the research: wine was selected as a high involvement product and a “cup of coffee” as a low involvement product. The reason for the product category selection was based on several criteria (Table 1). In the first place, we considered the consumption occasion for selecting the products, since the consumers were asked about their emotions when drinking wine in a restaurant in a “dining-out-of-home” context and when drinking a “cup of coffee” in a collective canteen at the workplace during a lunch break. Secondly, the price of the product was considered, being the price of a bottle of wine in a restaurant much more expensive that a “cup of coffee” in a canteen; since the price of a “cup of coffee” is cheap, being commonly one euro. In fact, according to Mittal (1989) the consumption of wine at a restaurant could be considered a high involvement product since it is costly and sometimes more expensive than the food. The third criteria is the decision making effort, given that the selection of a bottle of wine at a restaurant may entail some consumer effort; while the selection of simple “cup of coffee” at a workplace canteen does not seem to entail decision effort, since it is one of the most highly occurring consumption situations. In fourth place, we considered the importance given to the product brand, since consumers perceive differences among brands in high involvement products (Mittal, 1989). In this vein, wine could be considered a high involvement product, since consumers perceive inter-brand differences (Mittal, 1989), but when asking for a “cup of coffee” at the workplace, consumers do not select a specific coffee brand. Likewise, we considered the purchase risk as a variable influencing the product involvement (Mittal, 1989), since consumers are likely to feel involved about the product if they perceive the purchase to be risky. Finally, the social risk was considered, given that the type of product selected may have a social value (Bell & Marshall, 2003). Accordingly, the consumption of wine at the restaurant entails a social risk, given that the bottle of wine is often shared with others; but drinking a cup of coffee in the workplace does not entail social risks.

3.2Sampling and fieldworkThe focus of this research is based on the emotions arising from product consumption. For this reason, we asked: “how do you feel?”, when participants were drinking wine or a “cup of coffee”. Considering that emotion is an immediate response to stimuli, we measured consumers’ emotions while they were consuming the product in a real consumption setting – a restaurant or a workplace canteen –; allowing participants to consume their drink as part of their daily routine. More precisely, the participants were presented with a list of 16 proposed emotions and asked to rate them in order to describe their emotional experience when drinking wine or the “cup of coffee”.

We developed a convenience sample due to the relative ease with which participants could be encouraged to complete the questionnaire. Regarding wine, the research participants were contacted in leisure moments at restaurants when dining out of home through an intercept survey; and regarding the consumption of the “cup of coffee” participants were contacted in a lunch break at a self-service canteen at work. In addition, the participants were informed that the purpose of the research was to evaluate and measure their emotions experienced when consuming the product. Finally, a total amount of 570 questionnaires was gathered for wine, and 431 questionnaires were acquired related to the consumption of a “cup of coffee”. The fieldwork was carried out in Spain in April 2016.

In the last part of the questionnaire socio-demographic characteristics were captured. Regarding the sample profile, the 41.90% of the participants are female, while the 58.10% are men. A percentage of 35.90% of the participants are between the ages of 30 to 39, while the 26.15% were between 24–29 years old; and a 22.67% were between 40–49 years old. In terms of education level, 18.99% of participants have primary education, while a 32.79% have secondary education, and more than 40% of the participants have university studies. Regarding the annual average income, the greater percentage of participants (31.49%) has an income of 24.000–30.000€.

3.3Variables and scale developmentIn this research, we adopted the measurement scale developed and validated by Ferrarini et al. (2010) that describes the consumer immediate emotional experience and feelings elicited in wine consumption (Table 2). These emotional terms could be divided into two categories according to their valence or appraisal dimension, between positive/pleasant and negative/unpleasant- emotions. More precisely, the participants were asked to evaluate a 16 proposed emotions using a five-point Likert-type scale agreement questions, meaning 1=“totally disagree” and 5=“totally agree”, concerning the emotions they feel when drinking wine or when drinking a cup of coffee. Then, participants were asked regarding their satisfaction with the product. To measure consumer satisfaction, we used the items proposed by Tsiros, Mittal, and Ross (2004).

In this research, we adopted the measurement scale developed and validated by Ferrarini et al. (2010) that describes the consumer immediate emotional experience and feelings elicited in wine consumption (Table 2). These emotional terms could be divided into two categories according to their valence or appraisal dimension, between positive/pleasant and negative/unpleasant- emotions. More precisely, the participants were asked to evaluate a 16 proposed emotions using a five-point Likert-type scale agreement questions, meaning 1=“totally disagree” and 5=“totally agree”, concerning the emotions they feel when drinking wine or when drinking a cup of coffee. Then, participants were asked regarding their satisfaction with the product. To measure consumer satisfaction, we used the items proposed by Tsiros, Mittal, and Ross (2004).

4Results4.1Measurement model analysisConfirmatory factor analysis was developed through maximum likelihood with Amos 18.0, verifying the underlying structure of constructs. The first analysis clearly revealed the need to remove several items from the initial scale to assess emotions, since the values of their squared multiple correlations were lower than the threshold of 0.50 (Hair et al., 1998). Having removed these indicators, the results obtained showed an appropriate specification of the factorial structure. Then, the unidimensionality, reliability and statistical validity of the measurement model were analyzed (Table 3).

Confirmatory factor analysis was developed through maximum likelihood with Amos 18.0, verifying the underlying structure of constructs. The first analysis clearly revealed the need to remove several items from the initial scale to assess emotions, since the values of their squared multiple correlations were lower than the threshold of 0.50 (Hair et al., 1998). Having removed these indicators, the results obtained showed an appropriate specification of the factorial structure. Then, the unidimensionality, reliability and statistical validity of the measurement model were analyzed (Table 3).

First, the level of internal consistency in each construct was acceptable, with Alpha Cronbach's estimates ranging from 0.698 to 0.865 (Nunally, 1978). Second, all the composite reliabilities of the constructs (CR) were over the threshold of 0.70 ensuring adequate internal consistency of multiple items for each construct (Hair et al., 1998). Additionally, the convergent validity was satisfied, since all factor loadings exceeded 0.70 or reached close values (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Finally, the average variance extracted (AVE) of the constructs exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.50, indicating that a large portion of the variance was explained by the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Finally, the discriminant validity of the scale was evaluated for all possible paired combinations of the constructs. Correlation coefficients range from low (−0.072) to high (0.660), being significant at the 0.05 level. Then, the correlations between constructs were compared to the square roots of AVE extracted from the individual constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Our findings show that the square roots of AVE are higher than the correlation values, indicating an adequate discriminant validity of the constructs (Table 4).

Finally, the discriminant validity of the scale was evaluated for all possible paired combinations of the constructs. Correlation coefficients range from low (−0.072) to high (0.660), being significant at the 0.05 level. Then, the correlations between constructs were compared to the square roots of AVE extracted from the individual constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Our findings show that the square roots of AVE are higher than the correlation values, indicating an adequate discriminant validity of the constructs (Table 4).

4.2Measurement and metric invarianceIn order to examine the moderating role of product involvement, invariance tests of measurement model and structural model were conducted (Hair et al., 1998). First, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted for the two samples without factor loadings – unconstrained model –; and another analysis was developed will full factor loadings – full-metric invariance model –. Then, the two models were compared. The fit indices of the unconstrained model (RMSEA=0.074; CFI=0.952; TLI=0.928) and full metric invariance models (RMSEA=0.079; CFI= 0.948; TLI=0.905) show that both models achieve a good model fit. Additionally, the χ2 difference between both models (Δχ2=54.681) is significant (p=0.005), supporting full-metric invariance.

4.3Structural model analysisThe proposed structural model was then estimated. The model's fit as indicated by the adjustment indexes was deemed satisfactory. Our findings indicate that Chi-Square shows a significant value (χ2=296.376; p<0.000, df=46) so it could be considered a reliable indicator of model fit (Hair et al., 1998). Other absolute measures of the modeling adjustment such as the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI=0.951) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA=0.044) show adequate values. The measure of incremental fit and parsimony also indicate an adequate model fit, since the Incremental Fit Index (IFI=0.948), the Normed Fit Index (NFI=0.938), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI=0.928) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI=0.952) show values higher than 0.9 (Hair et al., 1998).

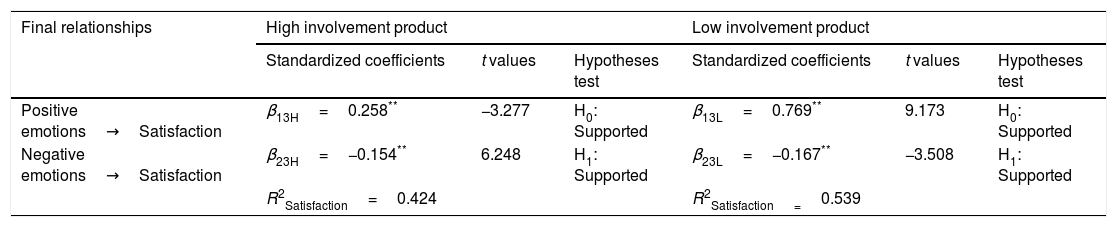

4.4Analysis of relationships among variablesThe research hypotheses test was developed through Structural Equation Modeling using maximum likelihood estimation. The data analysis indicates the direct influence of pleasant or positive emotions on consumer satisfaction, as well as an inverse influence of unpleasant or negative emotions on satisfaction; thus supporting the hypothesized relationships – H0 and H1 – (Table 5). In addition, our findings show that pleasant emotions drive consumer satisfaction and have a greater effect than negative emotions in terms of their influence on consumer satisfaction.

Final relationships and hypotheses test.

| Final relationships | High involvement product | Low involvement product | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized coefficients | t values | Hypotheses test | Standardized coefficients | t values | Hypotheses test | |

| Positive emotions→Satisfaction | β13H=0.258** | −3.277 | H0: Supported | β13L=0.769** | 9.173 | H0: Supported |

| Negative emotions→Satisfaction | β23H=−0.154** | 6.248 | H1: Supported | β23L=−0.167** | −3.508 | H1: Supported |

| R2Satisfaction=0.424 | R2Satisfaction=0.539 | |||||

The influence of positive emotions on satisfaction is stronger for the low involvement product (β13L=0.769**), rather than for the high involvement product (β13H=0.258**). Likewise, we found empirical evidence to propose an inverse relationship between negative emotions and consumer satisfaction for both high (β23H=−0.154**) and low involvement products (β23L=−0.167**). So, the positive influence of the pleasant emotions and the negative influence of unpleasant emotions on consumer satisfaction were identified. Conversely, in terms of the effect size of the influence of emotions on satisfaction, we came up with unexpected results, since positive emotions show a higher influence in satisfaction for the low involvement product. Therefore, our findings show that pleasant emotions exert a stronger influence on consumer satisfaction in low involvement products. One potential explanation might be that other variables qualify emotions as drivers of consumer satisfaction, such as the consumption situation.

4.5The moderating role of product involvementTo test the moderating role of product involvement, a multi-group analysis was developed comparing two sub-samples: high involvement product consumers (n=570), and low involvement product consumers (n=431). A validation of the specified proposed model was developed across the two groups of consumers, showing that the multi-group analysis could be performed (Hair et al., 1998). Then, an overall χ2 difference test was performed for the moderating variable–product involvement-. Model comparisons were conducted between the general model whereby the structural paths were freed across both groups and a model whereby the specified relationships were systematically constrained to be equal across the two sub-samples. A significant χ2 difference between the unconstrained and the constrained model indicates a moderating effect (Hair et al., 1998). The proposed model was estimated with all hypothesized parameters allowed to be estimated freely within each group (χ2=296.376; p<0.001; CFI=0.952). Then, in subsequent constrained models, the path coefficients of the relationships were constrained. The significantly χ2 higher values for the analyzed constrained models did not improve the model fit (Table 6), supporting the moderating role of product involvement on the relationships between positive emotions and consumer satisfaction (Δχ2=49.765; df=1, p<0.000). Likewise, the no significant values for the increase of χ2, suggest the lack of a moderating influence of product involvement on the negative emotions-consumer satisfaction link (Δχ2=0.006; df=1, p<0.000).

To test the moderating role of product involvement, a multi-group analysis was developed comparing two sub-samples: high involvement product consumers (n=570), and low involvement product consumers (n=431). A validation of the specified proposed model was developed across the two groups of consumers, showing that the multi-group analysis could be performed (Hair et al., 1998). Then, an overall χ2 difference test was performed for the moderating variable–product involvement-. Model comparisons were conducted between the general model whereby the structural paths were freed across both groups and a model whereby the specified relationships were systematically constrained to be equal across the two sub-samples. A significant χ2 difference between the unconstrained and the constrained model indicates a moderating effect (Hair et al., 1998). The proposed model was estimated with all hypothesized parameters allowed to be estimated freely within each group (χ2=296.376; p<0.001; CFI=0.952). Then, in subsequent constrained models, the path coefficients of the relationships were constrained. The significantly χ2 higher values for the analyzed constrained models did not improve the model fit (Table 6), supporting the moderating role of product involvement on the relationships between positive emotions and consumer satisfaction (Δχ2=49.765; df=1, p<0.000). Likewise, the no significant values for the increase of χ2, suggest the lack of a moderating influence of product involvement on the negative emotions-consumer satisfaction link (Δχ2=0.006; df=1, p<0.000).

5Discussion of resultsOur findings indicate that the influence of emotions on consumer satisfaction varies depending on the level of product involvement. More precisely, the results show that pleasant emotions exert a higher influence on consumer satisfaction for low involvement products, compared to high involvement products. Or in other words, the pleasant emotions derived from consumption have a stronger influence on satisfaction when consuming low involvement products. One possible explanation is that the occasion of consumption could be a key factor in the influence of emotions on consumer satisfaction. In the present study some consumers were asked about wine consumed in a restaurant in a “dining-out-of-home” consumption situation; while other consumers were asked about the emotions elicited by a “cup of coffee” consumed in a collective canteen in the workplace. So, it seems that the occasion of consumption may be strengthening – or qualifying – the experienced pleasant emotions to drive higher satisfaction. Thus, our findings suggest that the occasion of consumption contributes to modify and shape the emotional experience in product consumption. Hence, we propose that not only the valence – pleasant/unpleasant – of the consumption emotion is translated into consumer satisfaction with the product, but also the level of product involvement should be considered and the occasion of consumption. Additionally, the study contributes to the Theory of Hedonic Asymmetry showing the prevalence of positive emotions experienced in product consumption, regardless the level of involvement.

6ConclusionsPrevious literature has shown the importance of emotions in consumer satisfaction and consumer behavior; but the influence of product involvement on how consumption elicited emotions influence consumer satisfaction has not been explored. Our findings indicate that the level of product involvement influences how emotions drive satisfaction. Contrary to our initial expectations, positive emotions exert a higher influence on satisfaction for low involvement products, highlighting the relevance of product involvement. One potential explanation is that positive/pleasant emotions are also dependent on the consumption situation, which is a situational factor, and not only motivated by the degree to which the product relates to pleasure. That is, the consumption occasion may determine the influence of emotions on consumer satisfaction. Maybe, the satisfaction obtained by a hot “cup of coffee” during a break at the workplace is more strongly determined by emotions than the pleasure obtained by a cup of wine when dining out of home. This finding is consistent with prior research, showing that consumer involvement with a product category is influenced by situational factors (Bloch & Richins, 1983), which may be the case for the consumption of a “cup of coffee” at the workplace. Finally, our results are in line with Mittal (1989) and Barrett et al. (2007), who highlighted the relevance situational factors and the context of consumption in the emotional experience. So, it seems that the emotional aspects of consumption are strongly linked to the context of consumption, such as the occasion of consumption.

Consequently, we propose that some situational factors – such as the occasion of consumption – should be regarded as qualifiers to the emotions elicited in product consumption. These varying consumption situations would lead to higher positive emotions in a consumption occasion. So, we can state that a “cup of coffee” – a low involvement product – creates higher consumer satisfaction than drinking wine – a high involvement product –, due to the consumption occasion – a break during a workday –. This finding is also in line with Avnet, Laufer, and Higgins (2013) who supported that for low involvement products, consumers are less focused on the quality of their choices, but more on how they experience the outcomes. Hence, we support that the specific situation where the product is consumed influences the emotions experienced; in turn, influencing consumer satisfaction.

Further, our findings reveal that product involvement moderates the emotions-satisfaction link for positive emotions; but our results do not support the moderating role for the negative emotions-satisfaction relationship. Similarly, our results do not support the moderating role of the level of product involvement in the creation of consumer dissatisfaction. Additionally, we examined whether positive emotions are dominant when consuming high involvement products. Our findings report that, contrary to the initial expectations, positive emotions have a stronger impact on satisfaction for low involvement products. So, we propose that three different dimensions should be considered when analyzing the link between consumption emotions and satisfaction: the valence dimension of emotions, the level of product involvement; and finally, the consumption occasion, which may be acting as a qualifier for positive emotions. Likewise, this study provides empirical support for the Theory of Hedonic Asymmetry, since our findings show the prevalence of positive emotions elicited by products’ consumption, compared to negative emotions, regardless to the level of product involvement. Additionally, our findings show the impact of the valence dimension of emotions on consumer satisfaction, with positive/pleasant emotions leading to consumer satisfaction; while the negative/unpleasant emotions do not drive consumer satisfaction.

This study presents some limitations that need to be addressed. First, future studies could be developed considering products different from wine and low involvement products different from a “cup of coffee”, in order to increase the results’ generalizability. Second, our study did not consider the consumers’ attitude toward both products, which could influence the consumers’ emotions and behavioral responses. However, considering the scarce research on the influence of product involvement on emotions driving satisfaction, the present research might serve as a starting point in this field of knowledge.

Understanding how product involvement influences consumers’ affective responses and satisfaction has great relevance in the marketing area. The reason is that low involvement products, that are usually cheap, could engender great consumer satisfaction due to the context of consumption. Additionally, consumers that experience higher satisfaction are likely to spend more money on the product category. Therefore, marketing managers could manage and alter the context of consumption. For example, providing a nice decoration for a cafeteria, an attractive ambience for a coffee-shop and comfortable canteen facilities would enhance the consumer experience. Thus, marketers should examine the level of product involvement when attempting to fully comprehend consumers’ satisfaction.