Several research attempts contributed to the literature related to lifestyle market segmentation mainly aimed to define lifestyle segments on a given product/service market in a positivist perspective. However, there is a lack of research interest on a normative perspective, questioning lifestyle segmentation effectiveness to have a guidance for brands regarding how it impacts brand purchase intention in different product types and consumer groups in comparison to brand perceived value. Therefore, this research purposes to define a formulation understanding the impact of lifestyle segmentation on purchase intention in relation to brand perceived value. After defining lifestyle segments of four different product category consumers using an AIO scale approach; the relationships through lifestyle, brand value perception and purchase intention were analysed empirically by using multiple analysis methods for selected product categories. As a result, the lifestyle segmentation couldn't be defined as the main and direct driver of brand purchase intention while consumer's perceived values which are affected by lifestyle significantly impact the purchase intention and this value mapping varies across product categories.

On the road of building a successful marketing strategy for brands, segmentation is one of the critical steps to forge ahead. However, the consumer markets in general are getting much more complex year by year creating a pressure to target homogeneous subgroups within a total heterogeneous market. As an example, millennials are the new rising consumer groups all around the world on the last decade and Nielsen's Millennial Report (2014, p.3) states that “As a group, they're (Millennials) more diverse than any previous generation.” Then, the question of “How to manage this consumer complexity for brands” is getting more and more attention in the marketplace which ascribes again an ongoing care to market segmentation in the 2000’s. Not only in marketing academia, it is also welcomed by the marketing practitioners for the sake of managing the complexity since market segmentation enormously helps to clarify this complexity of managing the consumer needs & communication.

On the other hand, lifestyle (also called as Psychographic) segmentation is one of the sub-concepts associated with market segmentation in general which has increased its popularity by the late 1970’s & 1980’s, yet it protects this popularity in 2000’s. Because, the basic consumer dimensions such as demographics or geography could not be helpful enough to manage the above-mentioned market complexity and the practitioners started to search for a deep dive look to market segmentation concept to generate more detailed consumer knowledge (Gonzalez & Bello, 2002). On that sense, psychology discipline contributed a lot to develop lifestyle segmentation method for marketers. In this context, previous scholars generated new scales which enabled the practitioners to segment the markets by focusing on “lifestyle” dimension of the consumers.

The main objective of lifestyle market segmentation approach is to divide the different group of consumers on the basis of their lifestyles and personalities (Kotler, 1997). Following all the discussions and also the applications, lifestyle market segmentation has been defined as the better concept to provide more accurate and practical information about consumers for advertisers (Kamakura & Wedel, 1995).

On the other hand, lifestyle segmentation has been attacked by other scholars as well. For Yankelovic (2006), psychographics dimension is very weak in terms of the prediction of the consumers’ purchases. On this argument, Yankelovic points out the drivers of the consumers’ purchase decisions which may vary due to the various category specifications and that's why Lifestyle aspect of consumers may not be the significant driver of the purchase intention. But his argument was not supported by any empirical research data on his publication. Yet, further researches continued to be published mainly aimed to define the lifestyle segments of a defined sector/category (Johnson et al. 1991; Yang, 2004; Zhu et al. 2009; Suresh & Ravichandran, 2010). Thus, the scholars contributed to the literature on the way of clarifying the lifestyle segments of the various product/service categories.

Rudelius et al. (1987) highlighted that, in spite of the extreme importance of the market segmentation concept, marketing academia has not studied how it is actually implemented in practice and this is still a significant research gap in 2010’s valid for lifestyle segmentation, too (Jadczakova, 2013). Therefore, there is a lack of research in the literature focusing on an important general perspective: Understanding when lifestyle segmentation is impactful for brands operating in different product categories and how to formulate a distinction among product categories for these brands. So that, rather than only defining market segments of different categories based on lifestyle and having no idea about its impact on consumer behaviour change; this research purposes to contribute to the literature by focusing on the applicability & effectiveness of lifestyle segmentation explaining the impact on purchase intention of brands operating in different product categories. On a broader perspective, this research also aims to check for which product categories, lifestyle segmentation is impactful/applicable for brands depending on the brand perceived values of consumers affecting their purchase decisions. This could be a strong contribution to the literature in which Yankelovic had attacked to the productivity of lifestyle segmentation by rising the importance of category specific purchase intention drivers & values of the consumers.

2Literature review2.1Lifestyle segmentationSelect the right market segmentation base for a brand is precisely so strategic for practitioners in order to develop the right brand positioning proposal in a fierce competition. In parallel to this perspective, the main focus of segmentation concept in the literature is about selecting the segmentation base that is mainly classified as macro and micro (Feodermayr & Diamantopoulos, 2008) In this discussion, early market segmentation studies focused on mainly macro bases such as economic, demographic and geographic (Hassan & Craft, 2005).

On the other hand, some of the scholars stated their concern regarding the effectiveness of using the observable macro bases in market segmentation did not produce strong differences between groups. Thus, these bases may not allow the organizations to develop effective segmentation (McCann, 1974). For example, demographic characteristics of the consumers were limited to create homogeneous market segments on the way of organizations’ market segmentation studies. Because of such concerns and discussions, it is needed to have a deep dive look in market segmentation and understanding the consumers in a truly detailed manner since people having the same demographic variables might have so different attitudes & behaviours.

At this stage, marketers have linked their studies to psychology in a multidisciplinary perspective. As a result, the relationship between lifestyle patterns and consumer behaviour have been started to be studied since the 1960’s (Suresh & Ravichandran, 2010). Thus, the lifestyle concept has been introduced into segmentation research literature. William Lazer (1963, p.130) defined lifestyle as “a distinctive or characteristic mode of living in its aggregative and broadest sense, of a whole society or segment there of” As it could be inferred from the definition, starting by the 1960’s, scholars focused on consumers’ characteristic mode of living in order to better classify the segments. At this point, psychographic studies emerged in the marketing discipline as an answer to the need of in-depth market segment insight (Engel et al, 1990; Witzling & Shaw, 2018). Meanwhile, this new approach let the practitioners to better understand the consumer segments on the way of defining a precise marketing strategy.

Moreover, scholars also argued about how to place “Lifestyle” on consumer's decision path to purchase (Migueis et al., 2012). Kaze & Skapars (2011) suggested a hierarchical construct placing lifestyle as the determinant factor of attitude and fed by social values. Due to their “Consumer Purchasing Behaviour Process”, lifestyle is a key metric shaping the attitude and on the further stage, brand purchase decision as well.

In line with the psychographics integration to market segmentation literature, scholars attempt to contribute to the literature by providing different measures. One of the most widely used model measures activities, interest and opinions of the consumers which is called AIO scale, developed by Wells & Tigert (1971). The scale focused on how consumers spend their free time, what interested them and their opinion regarding their point of views on the various lifestyle patterns. In order to measure those dimensions, the authors used 300 AIO statements and in the operationalization process, the consumers having similar responses to the AIO statements forms the lifestyle segments. So that, different lifestyle segments mean the different “characteristic mode of living” in this measurement which gives the opportunity to the practitioners creating different marketing strategy or product/service solutions for the targeted lifestyle segment.

Moreover, different scholars conducted lifestyle measurement studies by producing the variations of AIO scale approach (Kucukemiroglu, 1999; Moore & Homer, 2000; Orth et al. 2004). Micro level scales were also developed to focus on sector-based lifestyle scale needs (Green et al. 2006). In terms of the evaluation of the scales used in the literature, AIO is one of the widely used lifestyle measurement scales which gives useful consumer typologies extracted by the cluster analysis of opinions, values and interests (Vyncke, 2002). In terms of the Means-End Chain Theory perspective, AIO scale is a very strong tool to predict the behaviour.

By using AIO and the other published lifestyle measurement scales, different micro level researches have been published particularly in the 2000’s & the 2010’s mainly aiming to define the specific markets’ lifestyle segments (Orth et al. 2004; Zhu et al 2009; Suresh & Ravichandran 2010; Diaz et al. 2018). However, there is no research published to focus on the brand as unity of analysis whether the lifestyle segmentation is applicable or not for various product or service segments.

2.2Perceived value and lifestyleOne of the significant arguments stated against lifestyle segmentation is its weak link to actual purchase behaviour. For Yankelovic (2006), psychographics could be used to capture some information about people's lifestyles and attitudes, but it is not a strong tool to predict the real purchase decision. In that sense, brand benefits and product features are much more critical affecting the consumer purchase intention.

Truly, the product and the brand name are capable of contributing several types of benefits to consumers due to their perception (Keller, 1993). According to this view, consumers perceive different benefits from the brands and assign values due to this perception. In that sense, it is critical to understand the meaning of “Perceived Value” served by the brand to the consumers. In the literature, one of the well accepted definitions of “Perceived Value” is suggested by Zeithaml (1988, p.14) as the following: Perceived value is the consumer's overall assessment of the utility of a product based on perceptions of what is received and what is given. Due to this definition, there is a consumer “Trade Off” as what is received and what is given and the consumer has an evaluation phase of the product utilities.

Following the definition of perceived value, it is obvious that perceived value is the end result of the evaluation of the consumer gain and the cost. Then, it is very critical to formulate the components of these “gains” or “benefits”. On the other side, there could be also different components of the “costs” (Sanchez et al., 2006). Yet, consumers evaluate their overall benefit by subtracting all the sacrifices from all the benefits in a multidimensional perspective. Therefore, multidimensional measures of perceived value could be accepted as the most developed and broad view of the measurement approach of perceived value since it is treating it as a multi-dimensional construct. This perspective is also logical when we evaluate that consumers are buying not only the product, also the total offered attributes of this product.

The leading and well-accepted multidimensional scale is PERVAL (Sweeney & Soutar, 2001) published to measure perceived value. Sweeney & Soutar constructed the scale by focusing on four dimensions: Functional value-price (Four items), functional value-quality (Six items), social value (Four items) and emotional value (Five items).

On the other hand, perceived value is a dynamic construct that changes from person to person. (Sanchez et al., 2006). The perception of value could be differentiated across different types of consumers with different expectations. In that sense, the link between lifestyle segmentation and perceived value is very critical. Due to all the previous studies and the theories, it is expected that there cannot be one unique perceived value of a defined brand for all the consumers and it differs due to the expectations of different consumer segments. Following Yankelovic's discussion (2006) on the applicability of lifestyle segmentation, it is crucial to understand the defined product class and brands’ perceived value to explain the reason of lifestyle segmentation efficiency for any defined product. Because, an effective lifestyle segmentation should have a positive effect on consumer behaviour which is fostered by the implementation of the designed marketing strategy & action accordingly.

Thus, we need to understand the relationship between perceived value & behavioural intentions. Accordingly, the critical discussion of perceived value is how it affects the behavioural intention. On this discussion, it is beneficial to analyse Green & Boshoff's (2002) argument on the relationship between perceived value and satisfaction. The model states that satisfaction is a strong predictor of value perception (Or, satisfaction helps to develop value perception). In addition, the second relationship is between perceived value & behavioural intentions that perceived value is a strong predictor of behavioural intentions (Or, perceived value mediates the relationship between satisfaction and behavioural intentions). Since a typical segmentation study should affect the consumer behaviour at the end, it is crucial to consider perceived value variable on a typical lifestyle segmentation research model.

2.3Purchase intention and lifestyleIn parallel to Means-End Chain Theory (Gutman, 1982), there is a strong connection between consumers’ lifestyle and their product preferences which is the main predictor of the actual purchase. In other words, lifestyle is a strong factor affecting the consumer's purchase behaviour across various products & services since these products & services reflect the consumers’ identities. Then, it is vital to understand how to predict the actual purchase behaviour of consumers on research models.

Wilkie (1970) found that brand purchase behaviour was predicted better by purchase intention scores. Similar to this perspective, further theories such as theories of reasoned action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) linked attitudes & intentions to actual behaviour. Another study has shown that consumers who stated intentions to purchase a product have higher actual buying rates than consumers having no buying intention (Berkman & Gilson, 1978).

In terms of the concept definition, Spears and Singh (2004, pp. 56) defined purchase intentions as “an individual's conscious plan to make an effort to purchase a brand”. Due to this definition, purchase intention is a kind of planned behaviour which to be turned to an action with the actual purchase in the future.

For the purpose of purchase intention measurement, it is concluded that Juster's probability of purchase scale (1966) is the most valid scale in the literature (Mortwitz, 2012). Juster contributed to the literature by publishing this scale and stated that using a purchase probability will help to define the large group of non-intenders into those who were more or less probable to buy. In that sense, Brennan and Esslemont (1994) proved by searching two food categories that Juster scale is more relevant and provided accurate forecast for the brand market shares compared to actual purchases.

We might recall that the opposite side against lifestyle segmentation mainly attacks to the limited effect of lifestyle segmentation on purchase intention. Then, it is crucial to measure the purchase intention affected by the lifestyle segments matching the targets of the brands.

Since the objective of lifestyle segmentation is to better construct the positioning and communication strategies for the targeted segments, it is expected to have a higher purchase intention rate of these targeted segment. Otherwise, we can't talk about the benefit of lifestyle segmentation approach.

3MethodologyIn accordance with the research purposes mentioned in the introduction, the research questions could be highlighted as below:

- 1)

Is lifestyle segmentation applicable for brands in different product categories?

- 2)

Is there a categorical difference on the effectiveness of lifestyle segmentation for brands?

- 3)

Is there a significant differentiation of the consumer lifestyle segments of the brands?

- 4)

How could a general perspective be constructed in terms of lifestyle segmentation efficiency by focusing on the perceived value of the brands?

The research methodology is formulated to answer above listed questions which will contribute to test the effectiveness of the lifestyle segmentation practices. Therefore, Figure 1 illustrates the research model of this study.

The first independent variable in this model is lifestyle segments. According to “Consumer Purchasing Behaviour Process” (Kaze & Skapars, 2011), lifestyle is the significant attribute affecting “Purchasing Decision” at the end point after “Attitude to Proposition”. Moreover, Means end Chain Theory (Gutman, 1982) supports this approach by linking product attributes to personal values. Therefore, lifestyle should be one of the factors affecting the purchase intention in parallel to this theoretical framework. Consumers should behave positively to purchase the brands sharing the same values reflected by the brand attributes. Thus, the first hypothesis is written as below:

H1 There is a significant difference between the lifestyle segments in terms of brands’ purchase intention.

As purchase behaviour is strongly predicted by the purchase intention (Wilkie, 1970), brand's defined targeted segments should have a differentiated purchase intention score compared the other non-targeted segments.

The second independent variable in the model is perceived value. As Sanchez et al. (2006) highlighted, perceived value is a subjective construct that varies between customers, person to person and cultures. As an example, Oh et al. (2010) pointed out that selected activities & interests had a positive effect on perceived value. Therefore, people having different lifestyles might have different perceived values of the same brand. Then, it is expected to have a relationship between lifestyle and perceived value. Thus, the second hypothesis of the research is defined as below:

H2 There is a significant difference between the lifestyle segments in terms of brand perceived value distribution.

In addition, Green and Boshoff's model (2002) discussing the argument on the relationship between perceived value and satisfaction gives an important perspective to understand perceived value's position on the research model. On this model, perceived value is a strong predictor of behavioural intentions and Chen & Chi (2018) supported this framework with their research results, recently. Then, it is expected to have an effect of perceived value on the relationship between lifestyle and purchase intention variables.

On the other hand, it is mentioned that the product and the brand name can contribute several types of values to consumers (Keller, 1993). For Yankelovic (2006) brand value has an important impact on purchase intention and depending on the type of the perceived value and its priority on the purchase decision, lifestyle effect on purchase intention might be lower or higher. Consequently, the third hypothesis is written as below:

H3 Perceived value affects the relationship between lifestyle and brand purchase intention (Green and Boshoff, 2002).

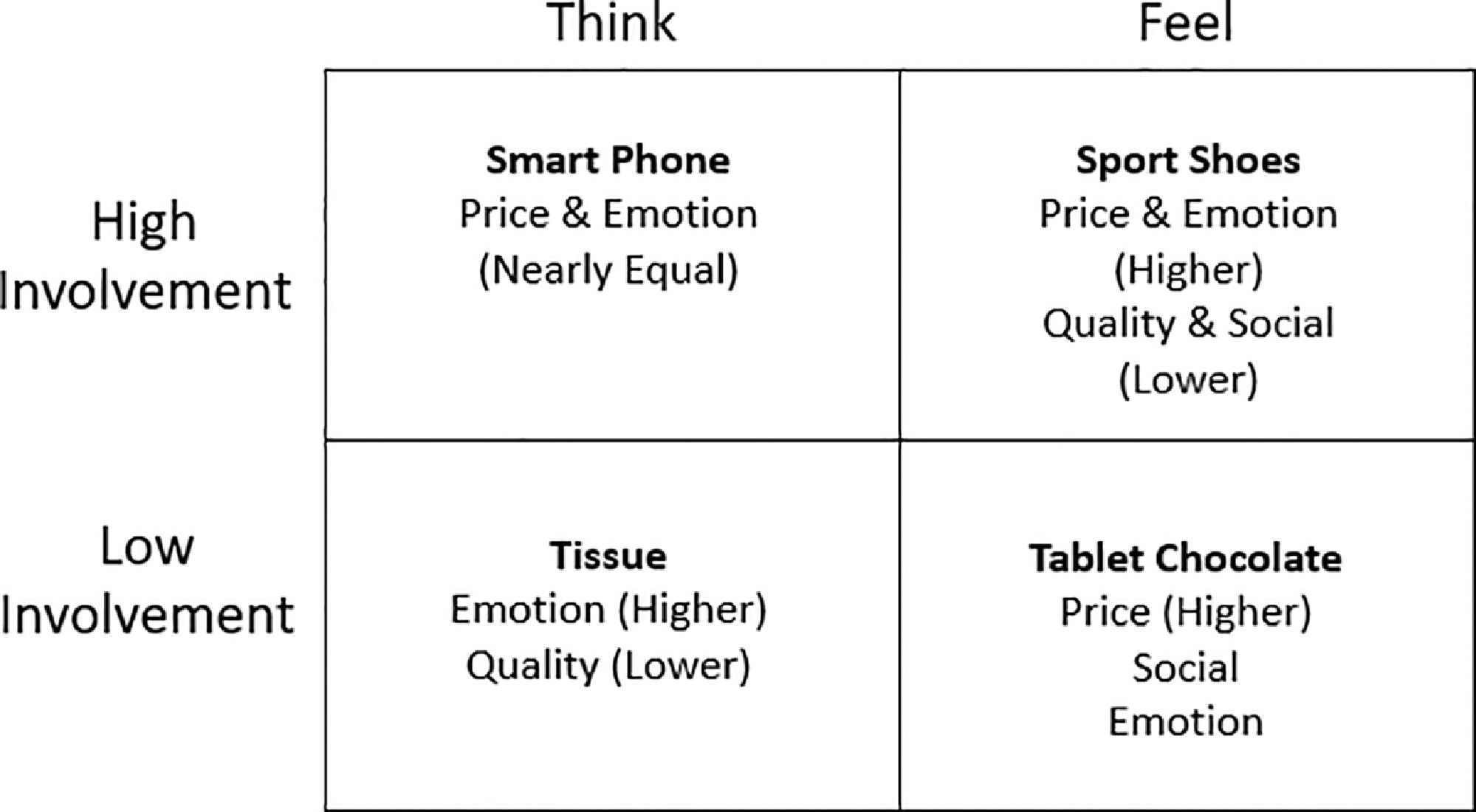

Moreover, brand perceived value can be varied depending on the type of the category/product (Sarıkaya & Sütütemiz, 2008). Then, it is not enough for brands to implement the research model only for one product category. In order to see the effect to brands on different product categories and to formulate a general look, the research model should be tested for various brands in different product categories. In this respect, Foote, Cone & Belding (FCB) grid (Vaughn, 1980) is used to define the product categories that must be covered. Because, the final objective of all segmentation studies is shaping the communication/advertising strategy of the brand and FCB grid is such a well-known tool classifying the product categories for the advertising need. Then, it is needed to cover FCB grids at least with one product category. So, the below product categories are selected, and the research hypothesis will be tested for all of these product category consumers buying different brands.

- 1.

High Involvement-Think: Smart Phone

- 2.

High Involvement-Feel: Sport Shoes

- 3.

Low Involvement-Think: Tissue

- 4.

Low Involvement-Feel: Solid Chocolate (Tablets)

Accordingly, the sample of the research will cover 4 sub-samples in order to conduct the comparative analysis between categories.

During the questionnaire design of the research, consumers’ lifestyle factors are measured by the AIO scale consists of 56 items which is previously used in Turkey before (Kucukemiroglu, 1999). This scale is also successfully implemented by different Turkish scholars (Kavak & Gumusluoglu, 2007). Regarding perceived value measurement, there are not so many widely accepted scales in literature, indeed and PERVAL scale developed by Sweeney and Soutar (2001) is the leading one in this respect (Sarıkaya et al, 2008). Moreover, purchase intention is the dependent variable in the research model and Juster scale (Juster, 1966) is used to measure purchase intention of the four category brands.

By using above-mentioned scales, this research focuses on the brands as unity of analysis and defines every segments’ purchase intentions for seven brands of every categories. It is expected to see whether the purchase intention is affected or not due to the change of lifestyle segments.

In this research, convenience sampling (Non-probability sampling method) is used since it is hard and expensive to implement a probability sampling method for all the consumers of the brands in every category. Rather than reaching to all lifestyle segments representing all the population, the success of the sampling is so dependent on having large sample sizes enough demographically scattered to reach different lifestyle groups as much as it can. That's why it is targeted to have minimum 300 respondents per categories and demographic quotas defined in order get dispersed samples representing the total Turkish internet users (TUIK, 2018).

In terms of data collection method, an on-line survey is designed. Following the focus group stage of the questionnaire design & check, online survey on SurveyMonkey Pro platform is implemented in Jan 2019 (in 4 weeks as data collection period) reaching to the real category consumers by the support of the filtering questions. In total, 885 respondents attended to this on-line survey. By 61% completion rate, 507 respondents were available for the analysis.

4Data analysis and findings4.1Sampling figuresOn Table 1, the breakdown of the total sample size can be reviewed. It is targeted to reach all the sub-segments of the demographics which is covering 16-50 aged respondents on a wide range of income levels. So that, we got the opportunity having a deep dive look to all the segment facts in a statistically meaningful manner.

Total Research Sample, Demographics

During the data collection phase, it was a must to include only the real consumer of the defined category brands, thus sample size varies due to this elimination. Smart phone category has the biggest sample size including 506 respondents, sport shoes, tissue and solid chocolate categories have 485, 441 and 384 respondents respectively. Thus, most of the respondents joined to more than one category survey since they actively consume various product categories & brands.

4.2Lifestyle & perceived value dimensions4.2.1LifestyleAt the first stage, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was employed to define the lifestyle factors by working on the AIO scale (Consist of 56 items) dataset. EFA was conducted separately for different category consumers’ AIO scale dataset, meaning 4 different lifestyle EFA processes. Table 2 contains the results of lifestyle EFA divided by four product categories.

Lifestyle Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) Results

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett test of sphericity results for all the lifestyle EFA's confirm the appropriateness of data for conducting the implemented factor analysis for all the product category samples. Calculated KMO & chi-square Bartlett test results are satisfactory since KMO value is higher than 0,6 for all samples & chi-square Bartlett test results are significant at 0,05 (Netemeyer et al. 2003; Bearden et al. 2011). Factors having the reliability score higher than 0,6 were included in the analysis for all product category samples since it is the lowest limit of reliability (Hair et al., 2006). Factors having eigenvalues higher than 1 were retained; items having factor loadings below .50 and items with high cross loadings were excluded.

Table 2 also summarizes the number of factors and explained variances by these factors. All total explained variances by category are sufficient since sum of explained variances are higher than 60% threshold level (Netemeyer et al. 2003; Bearden et al. 2011).

As a result, number of lifestyle factors defined nine for smart phone & sport shoes categories, eight for tissues and ten for solid chocolate. The only differentiated factors for smart phone & sport shoes are “Leadership” and “Self-Confidence” respectively. Regarding tissue category EFA results, there is a minor difference compared to smart phone and sport shoes categories: Total number of factors is eight for tissue category EFA whereas “Practical” factor is not found reliable. Moreover, solid chocolate category includes ten lifestyle factors higher than the other product categories’ number of factors since it additionally includes both “Leadership” and “Self Confidence” factors as reliable. Other seven factors are similarly found reliable for all categories.

4.2.2Perceived valueIn the research questionnaire, PERVAL scale's 19 items were placed and similar to lifestyle variable, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is employed to define the perceived value factors. In parallel to the literature, it is expected to reach four factors of the perceived value: Emotional, social, quality and price. Since the perceived value of a brand will change due to different categories and brands; PERVAL scale items were asked to the respondents separately for every product category samples considering their mostly used brands. Due to this fact, EFA was employed for four different product categories & brands dataset. Table 3 summarizes the results of perceived value EFA.

Perceived Value Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) Results

For both of these four consumer samples, all results of KMO measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett test of sphericity confirm the appropriateness of data for conducting the factor analysis for perceived value scale. For the first three product categories; “Emotional”, “Social”, “Price” and “Quality” are defined as reliable factors by the end of perceived value EFA process. However, solid chocolate is the only category different from the others. Quality factor is excluded in solid chocolate category EFA since the reliability score is lower than 0,6. This is an expected result since there was a question mark during the questionnaire design. Because, the “Quality” factor items cannot match “Quality” definition of some of the specific product categories, especially in food. As a result, quality factor is excluded from the analysis for solid chocolate.

4.3Segmentation by lifestyle in different product categoriesAs the next step, cluster analysis was employed to define the consumer segments based on lifestyle in different categories by only adding lifestyle factors to the analysis. Since lifestyle factors and samples change per categories, cluster analysis was implemented separately for every category consumer samples.

In terms of the methodology, two step cluster analysis method was used since sample sizes are large (Şchiopu, 2010). Following two step cluster analysis conducted for every category, lifestyle segments were defined as summarized in Table 4 and cluster quality marked as “Fair” for all the categories.

Number of segments, segments sizes & distributions are similar for smart phone and sport shoes categories since these category samples cover majority of the total research sample. However, these are different for tissue and solid chocolate segments as the samples also differentiate. Due to the number of lifestyle segments changing across category samples, lifestyle factor input predictors also change in defined segments.

For the lifestyle segments of smart phone & sport shoes categories, “family concern” and “fashion” are the leading lifestyle input predictors differentiated across the segments. As an understandable difference, “health/health concern” is the third important input predictor for sport shoes lifestyle segments. Segment 1 is shaped mainly by being strongly “family” & “fashion” oriented while these are the weak predictors for Segment 4. Segment 2 is differentiated with higher “diligent” and “health/health concern” scores whereas “leadership” is a strong predictor for Segment 3.

On the other hand, tissue category lifestyle segments are mainly driven by “health”, “leadership” and “homebody” predictors and Segment 3 is differentiated with high scores on these predictors. Segment 2 is strongly “family” and “fashion” oriented while Segment 1 has the weakest “health” and “leadership” scores.

Lastly, solid chocolate category has 2 lifestyle segments strongly differentiated by “leadership”, “family” and “self-confidence” predictors. Segment 1 has better scores in all of these three items compared to Segment 2.

4.4Hypothesis Testing4.4.1The impact of lifestyle on purchase intentionThe first hypothesis needs to be tested in the research model focuses on one of the main objectives of the study. It is questioned to understand whether the lifestyle segments are affecting the purchase intention of the brands and hypothesis is stated as below:

H1 There is a significant difference between the lifestyle segments in terms of brands’ purchase intention.

In order to test this hypothesis, MANOVA test was applied between the lifestyle variable (independent variable & nominal scale created by the lifestyle segments) and the purchase intention variable (dependent variable & interval scale). As a multiple analysis method, MANOVA test was implemented for all the four product category brands dataset and the results are summarized in Table 5. However, covariance matrices are not equal which blocks us to proceed on the MANOVA analysis since it is a parametric test.

H1 MANOVA Test, Box's Test of Equality of Covariance Matrices Results

| Box's Test of Equality, of Covariance Matrices* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart Phone | Sport Shoes | Tissue | Solid Chocolate | |

| Box's M | 163 | 278 | 200 | 46 |

| F | 1,9 | 3,2 | 3,5 | 1,6 |

| df1 | 84 | 84 | 56 | 28 |

| df2 | 231336 | 286457 | 108047 | 219925 |

| Sig. | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

Tests the null hypothesis

As a non-parametric test alternative to MANOVA, Multivariate Kruskal Wallis (MKW) was used to test H1 (Hair et al., 2006). In that sense, MKW analysis was implemented for all the product category brands & Table 6 summarizes the results.

Multivariate Kruskal Wallis Analysis of H1

Asymptotic significances are displayed. The significance level is ,05.

Due to the MKW test results on smart phone dataset, the null hypothesis -stating the purchase intention distributions are the same across the different lifestyle groups- is rejected only for Apple brand. That means lifestyle variable is not affecting the purchase intention scores of all the brands except Apple. Similar result is found on sport shoes category dataset as well. The null hypothesis is rejected only for “Others” brand. Other exceptions are Familia & Private Labels in tissue and Milka in solid chocolates. For all the other brands’ purchase intention distribution, there is no significant difference across lifestyle segments. In another explanation, consumers in different lifestyle groups do not have significant differentiation in terms of brand purchase intention distribution considering some of the exceptions highlighted above.

4.4.2The impact of lifestyle on perceived valueThe second hypothesis needs to be tested in the research model questions the relationship between lifestyle & brand perceived value variables. Therefore, the aim is understanding whether the lifestyle segments are affecting the brand perceived value of the customers or not. In another word, it will be clarified whether customers’ perceived value of a brand changes due to their lifestyle aspects. In that sense, the hypothesis is written as below:

H2 There is a significant difference between the lifestyle segments in terms of brand perceived value distribution.

In order to test this hypothesis, similar to H1, MANOVA test was applied between the lifestyle variable (Independent variable with a nominal scale created by the lifestyle segments) and the perceived value variable (Dependent variable with an interval scale). Following MANOVA test for the hypothesis test, Box's test of equality of covariance matrices are not equal except for solid chocolate category dataset as highlighted in Table 7. Due to this result, MANOVA could be implemented only for solid chocolate category brands dataset while MKW needs to be used for the others.

H2 MANOVA Test, Box's Test of Equality of Covariance Matrices Results

| Box's Test of Equality of Covariance Matrices* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart Phone | Sport Shoes | Tissue | Solid Chocolate | |

| Box's M | 45,9 | 83 | 50 | 12 |

| F | 1,5 | 2,7 | 2,5 | 2 |

| df1 | 30 | 30 | 20 | 6 |

| df2 | 270088 | 337664 | 127386 | 390698 |

| Sig. | 0,04 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,06 |

Tests the null hypothesis

Since, only solid chocolate dataset gives us the opportunity to proceed on MANOVA steps testing the hypothesis, the analysis was implemented and multivariate test results proved that there is a significant effect of lifestyle segments on perceived value distribution of the brands for this category. The limited effect size is 6,3% (Wilks' Lambda, Partial Eta Squared) at 0,05 significance level.

On the other side, MKW as a non-parametric option to test the hypothesis was implemented for smart phone, sport shoes and tissue product category brands. Table 8 highlights related results.

Multivariate Kruskal Wallis (MKW) Analysis of H2

Asymptotic significances are displayed. The significance level is,05.

The results provide that for both of the three product categories (smart phone, tissue, sport shoes) & for all the brand perceived value components, the null hypothesis is rejected. Thus, Ha is accepted which means that the distribution of all the perceived values are different across lifestyle categories. Hence, it could be interpreted that consumers in different lifestyle segments have different perceived value mapping across product categories. Accordingly, lifestyle is impactful on consumer perceived values.

4.4.3The impact of perceived value on purchase intentionDue to the definition and also the conditions needed for a moderation effect, there should be a significant relationship between an independent and dependent variable (Baron & Kenney; 1986; Namazi & Namazi, 2015). However, in our case, we could not verify a relationship between lifestyle and purchase intention tested by H1 process. At this stage, moderation or mediation of perceived value cannot be considered on the current model. That's why it is needed to revise the model to search for the effect of perceived value as an independent variable on purchase intention (See Figure 2).

One of the arguments of the scholars attacking to lifestyle segmentation effectiveness is based on the drivers of the purchase behaviour which might be affected by the value perceived by the consumers. Then, the research model is revised and the hypothesis 3R (Revised) is written as below.

H3R There is a significant effect of perceived value on brand purchase intention.

In order to test H3R, canonical correlation analysis was used for the four different category brands similar to other hypothesis processes we followed since there are four independent variables and seven dependent variables.

Regarding the independent variables, four perceived values were added to the canonical correlation analysis and these independent variables were named as Set-1. On dependent variable side, purchase intention scores of the brands (Seven variables) were placed and named as Set-2 for the analysis. Table 9 summarizes the variates produced on this analysis for different categories.

Canonical Correlations of the Variates by Category

On the first canonical analysis which was implemented for smart phone database, four canonical variates were produced in SPSS. But, only the first & second variates marked as significant at 0,05 level. Accordingly, other significant variates are V1 & V2 for both sport shoes and tissues. However, there is only one significant variate (V1) for solid chocolate.

On the second step, standardized canonical coefficients for Set 1 & Set 2 variables were checked and the coefficient scores having more than 0,3 canonical loadings were marked with “*” placement. These are highlighted in Table 10.

Standardized Canonical Coefficients for Set 1 by Product Categories

Moreover, only the coefficients of significant variates per categories were considered to mark. In that sense, it is clear that there is a significant effect of emotional & price on the correlation variates (Variate 1’s standardized canonical coefficient for emotional is -0,809 and 0,838 for price; Variate 2’s standardized canonical coefficient for emotional is -0,759 and -0,699 for price). The other categories’ effects were also summarized in Table 10. Normally, negative coefficients represent the inverse relationship but that is not the meaning as higher emotional value means lower purchase intention for all brands. At this stage, it is very important to check the correlations between Set 1 & Set 2 variables in Table 11 in order to understand the brand base effect and this part is one of the key contributions for brands.

Correlations Between Set 1 & Set 2 by Product Categories

As an example, when the correlations between Set 1 and Set 2 are checked, emotional has a positive effect for Apple (0,17) which means a higher emotional value effects positively the purchase intention of Apple. But this is negative for Casper (-0,15). This could be related to the situation as; the brands playing in price base competition (In Table 11, Casper has comparatively positive score in “Price” vs. Apple) are better affected by price while this can reduce the attractiveness for emotional value seeking customers.

Lastly, the proportion of Variance of Set-2 explained by opposite canonical variance gives us the idea of which variates explains the variance better. For smart phone brands; since Variate 1 has higher score, the standardized canonical coefficient of Variate 1 needs to be considered. Then, it is concluded that emotional & price are the values effecting purchase intention (CV1-1: 3%) for smart phone category which proves also H3R hypothesis.

For sport shoes, the first variate explains the higher proportion of variance of Set 2 (CV1-1: %4) In accordance to this, it is needed to focus on Variate 1’s standardized canonical coefficients in Table 10. In that sense, emotional & price are the stronger values effecting the relationship and then quality and social are also the other values having the effect of the overall relationship. This also confirms H3R hypothesis.

The third category analysed to test H3R is tissue. Again, there are two variates (Table 9; first: 0,398 and second: 0,229) which are significant at 0,05 level. For Variate 1, emotional and quality are the values having significant coefficients of Set 1 and for Variate 2, social and price are the significant values. The direction of the coefficients also differentiates between the brands. In order to see the most important values in the canonical correlations, it is needed to check the proportion of explained variance of Set-2 and explained variance is higher for Variate 1 (CV1-1: %4,4). Because of this, we might conclude that emotional and quality are the significant values effecting the overall relationship for tissue category. Thus, H3R is accepted for tissue category as well.

The last product category dataset is for solid chocolate brands. As a difference, there are only three perceived values entered to the analysis since quality factor was not significant on the factor analysis stage. There is only Variate 1 which is significant at 0,05 level (Canonical Correlation: 0,288). Price, social and then emotional are the significant values respectively affecting the overall canonical correlation and Set 2 variance explained by Variate 1 is 2%. Therefore, H3R is accepted in solid chocolate category dataset, too.

5Discussion and conclusionBy the help of all lifestyle market segmentation scales, many scholars contributed to the literature mostly defining the lifestyle segments in various product/service markets. However, it was a question mark for the scholars and practitioners whether lifestyle segmentation is applicable for brands effecting the “purchase” which needs to be tested empirically.

In accordance to this discussion, the first hypothesis tested in this research aimed to identify the effect of consumer lifestyles on brand purchase decision and also to see whether the effect changes in different product categories. Following the test results, it is found out that for both of the four product classes, we cannot claim a direct effect of Lifestyle on brand purchase intention except for some of the above-mentioned brands. This finding challenges the previous researches which only focused on the segmentation of consumers on the base of lifestyles for various product/service groups since the effectiveness of this segmentation route is not confirmed empirically.

On the other hand, since there is no direct effect of lifestyle in brand purchase intention, another research question was whether to see lifestyle's effect on perceived values of the brands. Therefore, lifestyle at this point could have an indirect effect to behaviour by effecting the perceived value. By testing hypothesis 2, it is aimed to understand different lifestyle groups’ differentiation in terms of their perceived value of their favourite brands. Then, it is reported after the statistical analysis that there is a significant difference of the consumers’ perceived values of brands depending on different lifestyle groups. This finding means that consumers do not expect the same value proposition from brands in a given product category due to their lifestyle groups. Therefore, different lifestyle groups perceive different value mix from the same brand. Since brand perceived value mix changes across different lifestyle segments, the meaning of the brand is not the same for different segments. As an example, Apple brand in smart phone category may signify mostly on quality as the leading value whereas this could be emotional for another segment. Therefore, brands need to focus on understanding these value mix perceptions of the segments.

Another aspect of the research is to see the effect of perceived values on brand purchase intention. Because, we might formulate a value mix for a defined brand in different product categories and understand the categorical differences. Following the analysis conducted to test Hypothesis 3, it is accepted that perceived values significantly affect brand purchase intention and this impact changes between different product categories. Since another research objective was to check this differentiation placing them on FCB matrix, the significant brand perceived values by product categories could be mapped as shown in Figure 3 below. The values are written depending on their effect sizes (Bigger on top and bold, lower on below).

Due to the above mapping, the effect of perceived values on purchase intention varies with respect to different product categories. As an example, emotional has a strong effect for smart phone category, but this effect is lower for solid chocolate.

On the other hand, regarding the direction of the effect (Positive or negative), it is needed to have a deep dive look on brand base split. Because, a perceived value could not always affect the purchase intention of all the brands positively which is proved in the analysis part of the research (See Table 11). If a consumer's main need is “Social” for a defined product, this will positively be related to her/his purchase behaviour for the brand serving & communicating the social value or the brand is positioned on this “Social” aspect. But, if another brand has a lack of its “Social” value, this means a negative effect on the purchase intention of customers for this given brand. As an example, Nike is the brand positively affected by social value on purchase intention in sport shoes category. However, Kinetix is negatively affected by this.

In relation to the other factors affecting the purchase intention, perceived value could neither be placed as a moderator nor a mediator factor affecting the main relationship between lifestyle and purchase intention. Yet, it is shown that lifestyle affects the perceived value of consumers and consumers’ perceived value drives their purchase intention accordingly. This finding proposes the following both for the practitioners and scholars: Perceived value is the factor significantly affecting the behaviour and lifestyle is only a dimension differentiating consumers’ perceived values of a given brand.

6Implications for brand managementRecently, practitioners have the doubt of the classical ways of segmentation in terms of their effectiveness on behaviour. That's why it is needed to have a challenging look to the researches on both academia & in practice and this research is one of these attempts. Therefore, the main takeaways of the practitioners functioning in brand management area could be summarized as below:

- •

Just as a sole dimension, lifestyle is not a strong market segmentation variable in regard of behaviour change objective since it does not affect the purchase intention directly.

- •

Rather than considering lifestyle as a sole dimension, the perceived value of the consumer that is shaped by lifestyle is much more important to drive the behaviour change.

- •

In that respect, it is critical to focus on consumer value expectation that is formed by lifestyle for a defined product/service category

In addition to this, brand management practitioners need to question the backgrounds of these four perceived values. Such as, finding quality dimension as an important value for the targeted segment is not enough. It is also critical to understand what the meaning of quality is for a given product or service. That's why, in a tailor-made research, it is needed to understand this meaning in detail.

7Limitations and future studiesAlthough, substantial contributions to the literature exist by the result of this research, further researches also need to consider two major limitations. Firstly, the study used a non-probability sampling method limiting us to represent the total population. Secondly, the research model is tested for the selected product categories to cover FCB grid classification. Therefore, different product categories might still have different results.

Accordingly, further researches might consider using a probability sampling procedure with a larger sample size. In addition to this, implementing a future study with many different product categories will strengthen the contribution by checking all these different product category value mappings.