The objective of this study was to analyze the influence of parents and Physical Education teachers on adolescent's extracurricular Physical Activity. Data were obtained from the Chilean System for the Assessment of Educational Quality test with a large representative sample of 23,180 students (11,927 females and 11,253 males aged 13.7 and 13.8 years respectively). The analyzed variables were the extracurricular physical activity of adolescents, parents’ and physical education teachers’ encouragement to do physical activity and parents’ physical activity behavior. Associations between variables were analyzed using chi-squared tests. Two logistic regression models, one adjusted and the other unadjusted, were performed for each physical activity variable (vigorous, moderate, mild and total) in order to obtain odds ratios from parents’ and physical education teachers’ influence variables. Results showed that parents’ influence is more relevant than physical education teachers’ influence in order to promote physical activity in adolescents, regardless of age, sex and physical condition.

El objetivo del estudio fue analizar la influencia de los padres y los profesores de Educación Física en la Actividad Física extracurricular de los adolescentes. Los datos fueron obtenidos del Sistema Chileno de Medición de la Calidad de Educación, en una muestra representativa de 23,180 estudiantes (11,927 niñas y 11,253 niños, con una edad media de 13,7 y 13,8 años). Las variables analizadas fueron la Actividad Física extracurricular de los adolescentes, la influencia que ejercían los padres y los profesores de Educación Física para que realicen Actividad Física y la Actividad Física de los padres. Se analizó la asociación entre las variables a través del chi-cuadrado. Dos regresiones logísticas, con y sin ajuste del modelo, fueron realizadas para cada nivel de la Actividad Física (vigorosa, media, baja y total) con el objetivo de obtener los Odds Ratios de las variables relativas a la experiencia de los padres y los profesores de Educación Física. Los resultados muestran que la influencia de los padres es más relevante que la de los profesores de Educación Física a la hora de promover la Actividad Física en los adolescentes, independientemente de la edad, el género o la condición física.

Physical Activity (PA) plays a substantial and independent role in the rate of BMI increase during adolescence (Kimm et al., 2005), and it has been widely associated with multiple benefits like reduced risk for developing metabolic syndrome in adulthood (Yang, Telama, Hirvensalo, Viikari, & Raitakari, 2009) and cardiovascular disease, among others. However, current PA levels in children and adolescents are insufficient to achieve health benefits (Rosenkranz et al., 2012) and some guidelines have been deliver by scientific literature (Saavedra, 2014). In Chile, the level of obesity and physical inactivity has increased in the last decades. Currently, it has the highest prevalence of overweight and obesity in all Latin America for people younger than 20 (37% and 31.6% for boys and girls respectively) and one of the highest for people older than 20 (67.9% and 63.9% for men and women respectively) (Ng et al., 2014), therefore it is a major public health problem. Maintenance of PA during adolescence could be a primary method for prevention of obesity and future chronic diseases development (Kimm et al., 2005), thus it is important to know the most important factors for adolescent to be physically active.

The role of parents (Silva, Lott, Mota, & Welk, 2014) and teachers (Standiford, 2013) has been established as a major factor in the promotion of PA in adolescents. Parents’ involvement in child's PA has a direct impact in PA levels during childhood and in the future as adults (Thompson, Humbert, & Mirwald, 2003). Parents, among others, determine which activities children can do and which resources they can access (Welk, Wood, & Morss, 2003), and they can influence children's activity in two ways: being a role model or by verbal motivation (Beets, Vogel, Chapman, Pitetti, & Cardinal, 2007). Other studies have confirmed the relationship between parents’ and children's PA levels, finding a higher influence of active parents than of those inactive (Welk et al., 2003). These results are useful to provide new strategies for promoting PA in children. Otherwise, Physical Education (PE) teachers need to increase the motivation of their students to be physically active, both in PE lessons and outside of school (Spray, 2002; Standage, Duda, & Ntoumanis, 2003). The improvement of teaching strategies in order to obtain effective motivation is essential to achieve higher PA levels (Rosenkranz et al., 2012). Currently, some studies have proved the usefulness of PE teachers training programs in improving their motivation style in order to enhance their students motivation, increasing their intentions to be physically active (Cheon, Reeve, & Moon, 2012).

Regular PA in adulthood is associated with healthy habits like not smoking, a healthy diet and body composition maintenance. Among adolescents, little or no involvement in PA is related with unhealthy habits, as among adults (Pate, Heath, Dowda, & Trost, 1996). Adolescence is an important stage where habits related to a healthy lifestyle are acquired, and these habits continue into adulthood (Lake, Mathers, Rugg-Gunn, & Adamson, 2006), therefore it is important to know which are the principal factors that influence the level of adolescents’ PA. There are no studies that analyze the interactive influence of parents and teachers jointly. In this sense, more studies are needed comparing and analyzing which of these factors, parents’ or PE teachers’ influence, is more relevant to the level of weekly PA in adolescents. The students’ perception of the behaviors of these agents could provide useful information to develop better initiatives to increase PA among adolescents. For this purpose we have used some questions from the questionnaire employed in the Chilean System for the Assessment of Educational Quality test (SIMCE) for PE 2012. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to analyze the influence of parents and PE teachers in adolescents¿ extracurricular PA.

MethodSampleThe Chilean Ministry of Education, in an attempt to assess the quality of Education, has standardized the System for the Assessment of Educational Quality test (SIMCE) in a national representative sample. In particular, PE was assessed in 2012 in eighth graders. Fitness assessment is the primary target of the SIMCE test for PE, but in 2012 a questionnaire containing items related to PA habits, nutrition and questions about parents and PE teachers was included in the evaluation.

In 2012, the SIMCE for PE was carried out in a major and representative part of the 8th graders of Chile (N=29.558), distributed in 662 schools and 997 classes, except Easter Island, Juan Fernandez archipelago and Antarctic region. Examiners were recruited through an open announcement. The recruitment process was carry out by the National Institute of Sport and all of them were technicians from this institution or Graduates in Physical Education. Additionally all examiners received a testing manual which described all the test procedures and protocols and completed a training course in order to improve the reliability and validity of the test. SIMCE certified the validity of the field test and collected data (Ministry of Education, 2014).

MeasurementsExtracurricular physical activity. In order to measure the PA of students during the week, they were asked the following questions: Thinking about a whole week, from Monday to Friday, how much time do you spend practicing the following activities? (a) Go for a bicycle ride or skating; (b) jumping, running, playing with a ball or other similar games; and (c) playing sports or attending a dance academy or a workshop on PA (apart from PE classes at school). The same questions were asked regarding these activities during the weekend. These questions were interpreted as mild PA (a), moderate PA (b) and vigorous PA (c) according to the similarities with the examples of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire for each PA category (Hallal & Victora, 2004). Responses were broken down in order to have all weekly activity for each variable, and a new variable was created considering the total weekly PA. PE time was intentionally excluded. In Chile, the curriculum varies according to the school institution, changing PE hours from 2 to 4.

In order to measure the parents¿ and teacher's influence in participants¿ weekly PA, the following questions were asked: (a) Regarding your parents, do they practice sports and engage in PA? (b) Regarding your parents, do they encourage you to practice sports and engage in PA?; (c) Regarding your PE teacher, does he/she encourages you to engage in PA outside the school? Answers were rated on a Likert-type scale of four values (strongly agree, agree, disagree and strongly disagree).

Additionally, participants’ fitness was measured according to six tests subdivided into muscle performance (short crunches, standing long jump and push-ups), flexibility (sit and reach) and cardiovascular endurance (Cafra and Course-Navette) (Montecinos et al., 2005). Using the scores obtained from these tests, SIMCE office calculated two new variables in order to classify participants based on their fitness performance according to sex and age: (a) Structural Index using scores from muscle performance and flexibility tests and (b) Functional Index using scores from Course-Navette and Cafra tests. Participants were categorized into two possible groups according to test results. If the student was assessed satisfactory in all the test of an index, in function of cut offs point for age and sex, it will be classify as satisfactory in the correspondent index (Ministry of Education, 2014).

PA variables, parents’ and teachers’ influence variables were broken down as dichotomous variables in order to perform some statistical analysis.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics, with means and standard deviation or frequencies and percentages–depending on the nature of the variables–were done. The association between variables was analyzed using the chi-squared test. Two logistic regression models were developed for every dichotomized PA variable, namely an adjusted model and an unadjusted model. Engaging in some hours of weekly PA served as the reference level. The unadjusted models only included parents¿ and PE teachers¿ influence variables (also dichotomized) as predictors, whereas for the adjusted models, the following confounders were included: age, sex, structural index and functional index. For each model, the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) and their respective significances were determined, and the Hosmer and Lemeshow test for goodness-of-fit assessment of models were performed. All analysis were performed using SPSS for Windows. Statistical significance was set at p<.05

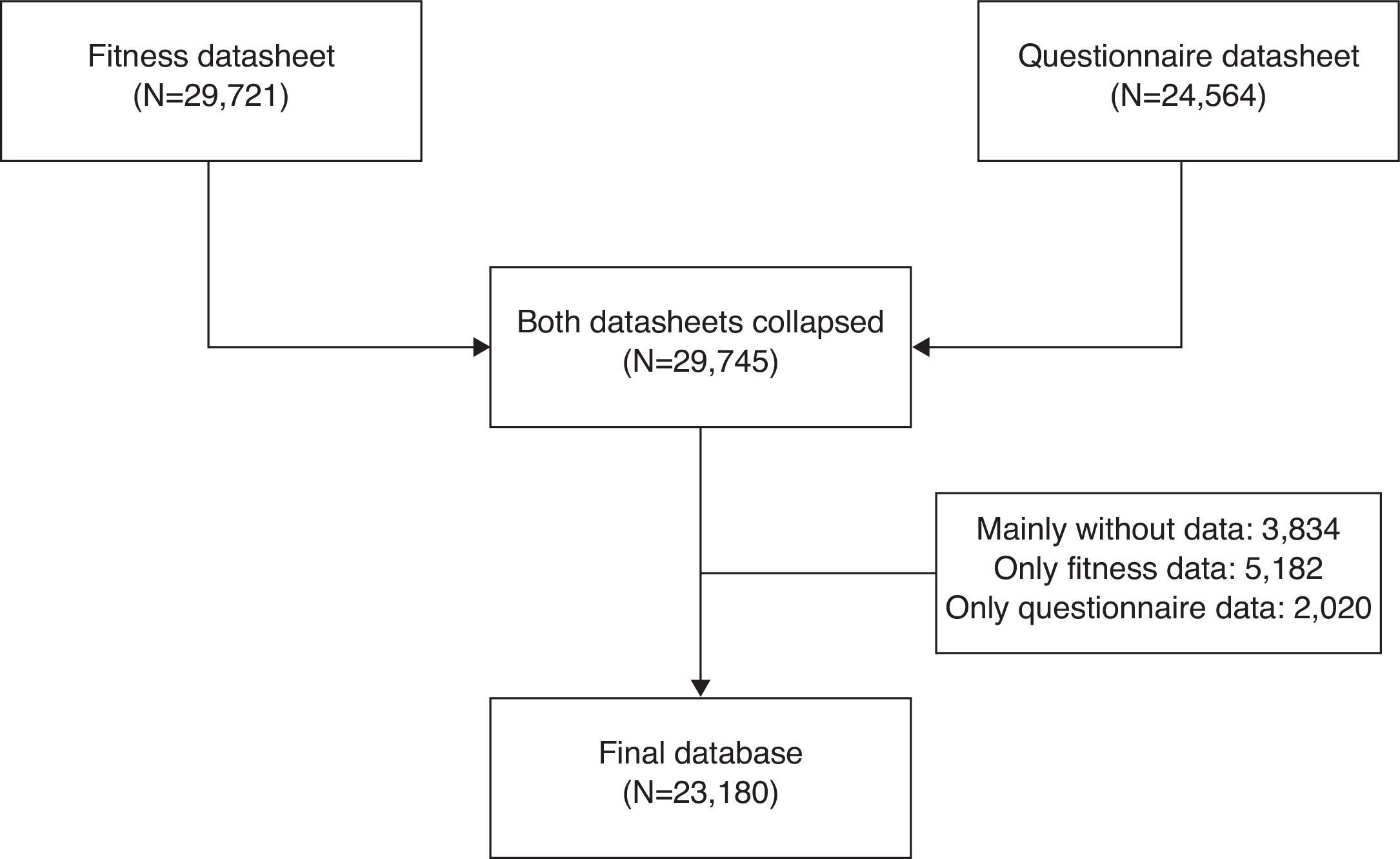

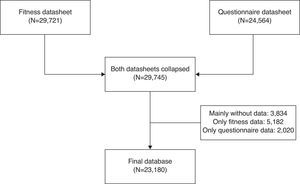

ResultsTwo datasheets were obtained from the SIMCE office, one with fitness data (n=29,721) and one with questionnaire data (n=24,564). Both datasheets were broken down and cleaned in order to have a full database with all the data from SIMCE on PE for 2012. A final database with a sample of 23,180 adolescents (11,927 females and 11,253 males aged 13.7±0.7 and 13.8±0.8 respectively) was obtained after removing participants who were found only in one datasheet or mainly without data (see Figure 1). Due to the great amount of sample and the characteristics of the study, there were participants who had missed data in some variables. The final sample differs according to variables included in each analysis, ranging from 16,839 (for regression analysis) to 23,180.

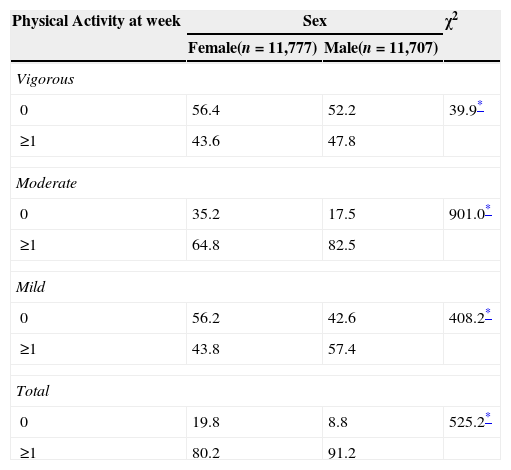

Results show that there were associations between sex and amount of PA in mild, moderate, vigorous and total activity (see Table 1). Boys practice more PA than girls in all levels of PA. The type of PA that more participants do is moderate, related with play jumping, running, playing with a ball or other similar games.

Percentage of participants who do some hour of weekly physical activity by sex.

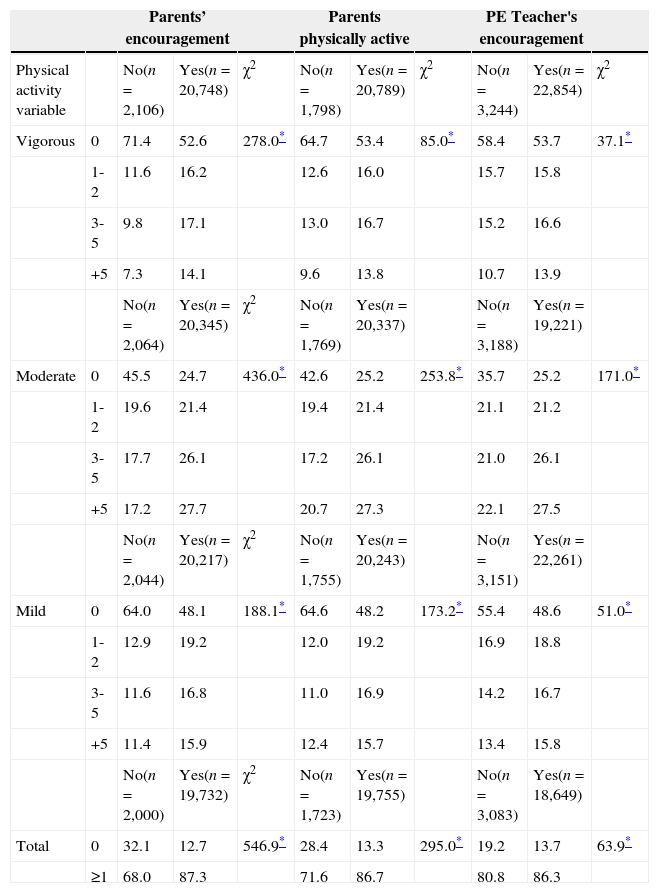

Table 2 shows the percentage of participant's weekly PA hours for each type of activity based on responses to the questions about parents and PE teacher. There was a statistically significant association between both parents’ and PE teacher's questions and weekly practice hours for all types of analyzed PA.

Weekly physical activity based on parents’ and PE teacher's influence to practice sports and physical activity.

| Parents’ encouragement | Parents physically active | PE Teacher's encouragement | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity variable | No(n=2,106) | Yes(n=20,748) | χ2 | No(n=1,798) | Yes(n=20,789) | χ2 | No(n=3,244) | Yes(n=22,854) | χ2 | |

| Vigorous | 0 | 71.4 | 52.6 | 278.0* | 64.7 | 53.4 | 85.0* | 58.4 | 53.7 | 37.1* |

| 1-2 | 11.6 | 16.2 | 12.6 | 16.0 | 15.7 | 15.8 | ||||

| 3-5 | 9.8 | 17.1 | 13.0 | 16.7 | 15.2 | 16.6 | ||||

| +5 | 7.3 | 14.1 | 9.6 | 13.8 | 10.7 | 13.9 | ||||

| No(n=2,064) | Yes(n=20,345) | χ2 | No(n=1,769) | Yes(n=20,337) | No(n=3,188) | Yes(n=19,221) | ||||

| Moderate | 0 | 45.5 | 24.7 | 436.0* | 42.6 | 25.2 | 253.8* | 35.7 | 25.2 | 171.0* |

| 1-2 | 19.6 | 21.4 | 19.4 | 21.4 | 21.1 | 21.2 | ||||

| 3-5 | 17.7 | 26.1 | 17.2 | 26.1 | 21.0 | 26.1 | ||||

| +5 | 17.2 | 27.7 | 20.7 | 27.3 | 22.1 | 27.5 | ||||

| No(n=2,044) | Yes(n=20,217) | χ2 | No(n=1,755) | Yes(n=20,243) | No(n=3,151) | Yes(n=22,261) | ||||

| Mild | 0 | 64.0 | 48.1 | 188.1* | 64.6 | 48.2 | 173.2* | 55.4 | 48.6 | 51.0* |

| 1-2 | 12.9 | 19.2 | 12.0 | 19.2 | 16.9 | 18.8 | ||||

| 3-5 | 11.6 | 16.8 | 11.0 | 16.9 | 14.2 | 16.7 | ||||

| +5 | 11.4 | 15.9 | 12.4 | 15.7 | 13.4 | 15.8 | ||||

| No(n=2,000) | Yes(n=19,732) | χ2 | No(n=1,723) | Yes(n=19,755) | No(n=3,083) | Yes(n=18,649) | ||||

| Total | 0 | 32.1 | 12.7 | 546.9* | 28.4 | 13.3 | 295.0* | 19.2 | 13.7 | 63.9* |

| ≥1 | 68.0 | 87.3 | 71.6 | 86.7 | 80.8 | 86.3 | ||||

Note. PE: physical eduction.

The percentage of adolescents who were totally sedentary was higher for those who reported their parents did not encourage them to practice sport (32.1%) or whose parents were not physically active (28.4%), while it was lower in those who reported their PE teacher did not encourage them to practice PA. Analyzing adolescents who did not engage in PA by category, percentages were higher in those who reported their parents did not encourage them to practice sport or their parents were not physically active.

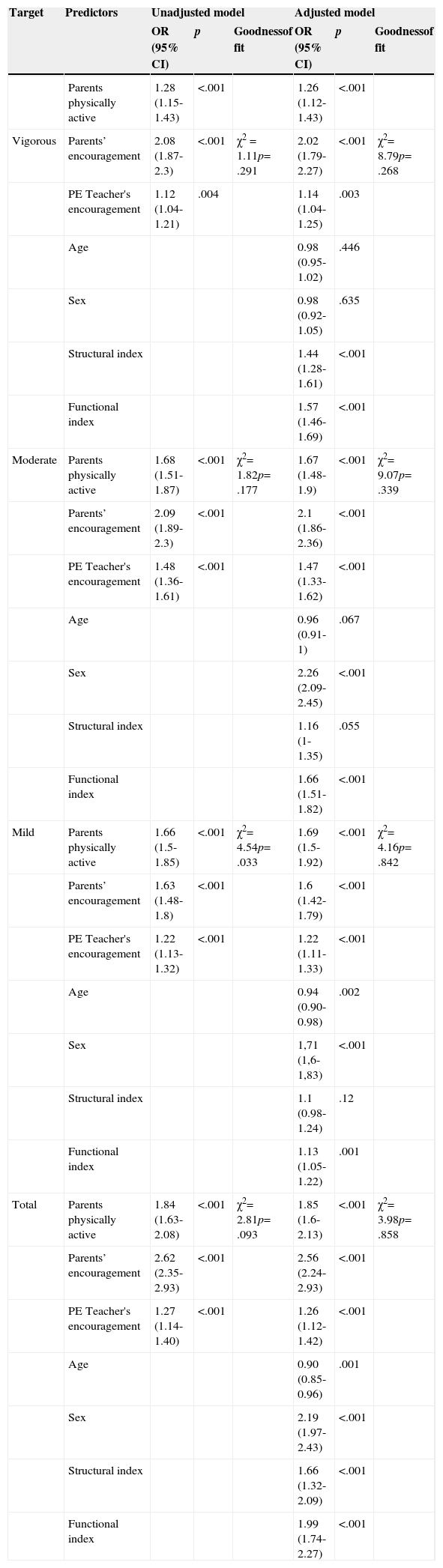

The unadjusted and adjusted ORs obtained for each type of PA variable, their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI), and their p values are shown in Table 3. The unadjusted model for mild PA was the only one that did not show significant goodness of fit, but it was improved in the adjusted model. For both, the unadjusted and adjusted model, the OR for the questions related to parents (to encourage to practice sports and physical activity and to be physically active) was higher than the question related to PE teacher encouragement. Based on OR, sex was the most important confounder in all models except for Vigorous PA. OR for functional index was always higher than structural index, and OR for age was near 1 for all models.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for physical activity variables.

| Target | Predictors | Unadjusted model | Adjusted model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | Goodnessof fit | OR (95% CI) | p | Goodnessof fit | ||

| Parents physically active | 1.28 (1.15-1.43) | <.001 | 1.26 (1.12-1.43) | <.001 | |||

| Vigorous | Parents’ encouragement | 2.08 (1.87-2.3) | <.001 | χ2=1.11p= .291 | 2.02 (1.79-2.27) | <.001 | χ2= 8.79p= .268 |

| PE Teacher's encouragement | 1.12 (1.04-1.21) | .004 | 1.14 (1.04-1.25) | .003 | |||

| Age | 0.98 (0.95-1.02) | .446 | |||||

| Sex | 0.98 (0.92-1.05) | .635 | |||||

| Structural index | 1.44 (1.28-1.61) | <.001 | |||||

| Functional index | 1.57 (1.46-1.69) | <.001 | |||||

| Moderate | Parents physically active | 1.68 (1.51-1.87) | <.001 | χ2= 1.82p= .177 | 1.67 (1.48-1.9) | <.001 | χ2= 9.07p= .339 |

| Parents’ encouragement | 2.09 (1.89-2.3) | <.001 | 2.1 (1.86-2.36) | <.001 | |||

| PE Teacher's encouragement | 1.48 (1.36-1.61) | <.001 | 1.47 (1.33-1.62) | <.001 | |||

| Age | 0.96 (0.91-1) | .067 | |||||

| Sex | 2.26 (2.09-2.45) | <.001 | |||||

| Structural index | 1.16 (1-1.35) | .055 | |||||

| Functional index | 1.66 (1.51-1.82) | <.001 | |||||

| Mild | Parents physically active | 1.66 (1.5-1.85) | <.001 | χ2= 4.54p= .033 | 1.69 (1.5-1.92) | <.001 | χ2= 4.16p= .842 |

| Parents’ encouragement | 1.63 (1.48-1.8) | <.001 | 1.6 (1.42-1.79) | <.001 | |||

| PE Teacher's encouragement | 1.22 (1.13-1.32) | <.001 | 1.22 (1.11-1.33) | <.001 | |||

| Age | 0.94 (0.90-0.98) | .002 | |||||

| Sex | 1,71 (1,6-1,83) | <.001 | |||||

| Structural index | 1.1 (0.98-1.24) | .12 | |||||

| Functional index | 1.13 (1.05-1.22) | .001 | |||||

| Total | Parents physically active | 1.84 (1.63-2.08) | <.001 | χ2= 2.81p= .093 | 1.85 (1.6-2.13) | <.001 | χ2= 3.98p= .858 |

| Parents’ encouragement | 2.62 (2.35-2.93) | <.001 | 2.56 (2.24-2.93) | <.001 | |||

| PE Teacher's encouragement | 1.27 (1.14-1.40) | <.001 | 1.26 (1.12-1.42) | <.001 | |||

| Age | 0.90 (0.85-0.96) | .001 | |||||

| Sex | 2.19 (1.97-2.43) | <.001 | |||||

| Structural index | 1.66 (1.32-2.09) | <.001 | |||||

| Functional index | 1.99 (1.74-2.27) | <.001 | |||||

Note. PE: physical education.

This paper presents an analysis on the influence of parents’ and PE teacher's encouragement in adolescents to be physically active using a large nationally representative sample from Chile. Results indicate that parents’ influence is more relevant than PE teachers’ influence in order to promote PA in adolescents, regardless of age, sex and physical condition.

Results showed that more than 50% of participants did not engage at any time in vigorous PA in a week (playing sports, dancing or attending a workshop on PA apart from PE classes at school), and additionally, 35% of females did not engage in moderate PA in a week (jumping, running, playing with a ball or other similar games). These results match data from Latin America from previous studies, and corroborate the high prevalence of characteristic sedentary behaviors in the Latin American Region (Hallal et al., 2012).

Considering the recommendations of World Health Organization for weekly PA (World Health Organization, WHO, 2010) and the importance of PA for the prevention of diseases (Lee et al., 2012), the Chilean Ministry of Education has recently changed the PE curricular bases in order to give more importance to health promotion in this subject at schools (Ministry of Education, 2013). Ministry of Education changed the name of the subject from Physical Education to Physical Education and Health (MINEDUC, 2013). Although results in this study indicate that the encouragement of PE teachers to practice sport is not very relevant for adolescents in order to be physically active, benefits in children's PA outside the school in response to PE teachers’ influence have been proved previously (Cheon et al., 2012; Rosenkranz et al., 2012). These studies were focused on the improvement of motivational strategies in PE classes, more than just encouraging students to practice outside the school. Strategies are oriented to satisfy psychological key needs such as autonomy, competence and relationship. Results of our study show a smaller importance of the PE teacher's influence on PA levels in children, but is also relevant. Notwithstanding, it is necessary for teachers to know these strategies to increase their influence on their students, so they feel themselves more motivated to practice more PA in their leisure time (Chatzisarantis & Hagger, 2009).

Nevertheless, our results show that the influence of parents is more relevant than that of the PE teacher for adolescents in order to engage in PA. Specifically OR showed that the probability to engage in some PA increases 156% when adolescents are encouraged by their parents to practice sports and 85% when their parents are physically active, while this probability was only increased by 26% when they were encouraged by their PE teacher. Some studies have previously confirmed parents’ influence on children's physical activity showing that parents are a key factor in health-related behavior development of children. Depending on parents’ behaviors, children could inhibit or promote their PA (Beets et al., 2007; Edwardson & Gorely, 2010a). Our results indicate that encouragement of parents for their children to engage in PA is highly associated with the amount of PA that the children do, regardless if it is vigorous, moderate, mild or total PA. Previous studies examining the relationship between parental correlates and young people's physical activity including encouragement to engage in PA have produced mixed results regarding parents’ encouragement (Edwardson & Gorely, 2010b). Some have concluded that encouragement is positively related to young people's PA (Edwardson & Gorely, 2010b; Pugliese & Tinsley, 2007), while others have reported indeterminate relationships or no association (Ferreira et al., 2007; Sallis, Prochaska, & Taylor, 2000). Our results provide more information about this topic, giving importance to parents¿ encouragement. In view of this, policies to promote physical activity in children and adolescents should consider parents’ influence in order to succeed. There is evidence to suggest that lifestyle intervention effectiveness can be enhanced by including parents (Dellert & Johnson, 2014).

Regarding sex influence on engaging in PA, results showed it is a major issue. Near 20% of female participants reported that they do not engage in any weekly PA, while this number was 9% for males. Regarding regression analysis, sex was not significant for the vigorous PA model, but it was important for moderate, mild and total PA (OR values of 2.26, 1.71 and 2.19 respectively). The absence of differences in vigorous PA could be due to the questionnaire used. Students were asked about “dance and sports”, being an activities more proper of girls, compared with the activities in, i.e., moderate PA, “jumping, running, playing with a ball or other similar games”. Differences in PA by sex have been previously studied and it is well established that, in general, females report a higher level of sedentary lifestyle than males (Bauman et al., 2012). There are three major themes that affect girls’ physical activity, perceptual influences (i.e. girls need to feel and look feminine or they have to have fun during physical activity); interpersonal influences (i.e. ability comparison and competition or family, peer and teacher influences); and situational influences, such as accessibility and availability or physical activity and gender role (Standiford, 2013). Social environment must improve girls chance to be physically active and help them to increase their level of PA so parents not only can influence children through encouragement, but by being a role model they engage them in PA or they support the type of activity the children choose (Wright, Wilson, Griffin, & Evans, 2010). There is a need for more studies analyzing the effects of parents’ and teacher's influence in adolescents to be physically active, mostly longitudinal studies.

LimitationsThis study has some limitations that need to be reckoned. The variables of parents’ and teacher's influence for adolescents to be physically active and the questions about the amount of PA used in this study could be measured more deeply with other validated instruments. However, due to the great size of the sample, it is very difficult to add instruments with more than one question for a variable. However, all items used in SIMCE were extracted from validated questionnaires with international relevance, such as the Spanish version of Global School-based student health survey and California Healthy Kids Survey (Ministry of Education, 2014). Additionally, in this study the classification of PA into vigorous, moderate and mild, was made using questions about different activities instead of intensity, but these activities are similar to those used in the examples of internationally recognized questionnaires like iPAQ (Hagstromer, Oja, & Sjostrom, 2006).

ConclusionsParents have a bigger influence in adolescents than PE teacher in adolescents for them to be active. Additionally, parents¿ encouragement to practice sports and PA is more related to it than parents’ behaviors on adolescents¿ physical activity. Results indicate that political efforts aimed to reduce sedentary behaviors in adolescents should be focused on parents more than on PE teachers. Ministry, at national level, and schools, at local level, have to implement policies of parent's education. Recommendations of quantity and quality of PA in children have been addressed prior in scientific literature (Saavedra, García-Hermoso, Escalante, & Domínguez, 2014; Slentz, Houmard, & Kraus, 2007), but related to parents it is scarce. Public agents have to inform and instruct parents and families in PA and health, promoting familiar activities where all members can successfully participate. Moreover, school-based interventions cannot be implemented independently of other strategies. The role of PE teacher or health professional, as was previously indicated (Naylor & McKay, 2009), is important to encourage parents in order to pinpoint the importance of family based activities.

Available online 28 February 2015