Global variations in the prevalence of asthma and related diseases have suggested that environmental factors are causative, and that factors associated with urbanisation are of particular interest. A range of definitions for ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ have been used in articles on asthma and related diseases, making it difficult to assess their importance as aetiological factors. This study sets out to examine such definitions used in the literature.

MethodsMedical and social science databases were searched for articles that made distinctions of ‘urban’ and/or ‘rural’ in the context of asthma and related diseases.

ResultsThe search identified 73 articles and categorised four types of definitions. A specific definition of urban or rural was used in 19 (26%) articles. Nine (12%) articles used non-specific and/or administrative definitions. There were 23 (32%) articles that described locations as ‘urban’ or ‘rural’ but did not indicate if the description defined ‘urban’ or ‘rural’. Distinctions were made between urban and rural locations without a description or definition in 22 (30%) articles.

ConclusionsThere is substantial variation in the definitions of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ in articles regarding asthma and related diseases. It would be advantageous to have clearer and more precise definitions of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ which could facilitate aetiological research and also comparisons between locations, especially in international studies.

Global patterns in the prevalence of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema symptoms have been identified by The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) and pointed to environmental factors as potentially causative.1–4 The increasing burden of these diseases around the world has emphasised the importance of epidemiological studies of specific environmental factors,5 with urbanisation being of particular interest.6 Distinct urban–rural differences have been observed in many locations, especially in several African studies where lower levels of asthma were found in rural than urban areas.7–9 Increases in prevalence of asthma symptoms over time have been associated with rural–urban transitions10 and there is evidence to demonstrate that increasing asthma trends may have reached a plateau in most urbanised English language and Western European countries.11 These trends suggest that global changes in the prevalence of asthma and related diseases, which occur with changes in environmental conditions,5,11,12 may be affected by specific aspects of urbanisation.

However, there is currently no standard definition of urbanisation and studies use a wide range of approaches to make the distinction between ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ locations. The absence of a universal method of defining ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ creates difficulties in pursuing aetiology and comparing studies. Dichotomised distinctions within countries will not reflect levels of urbanisation within or between countries which comprise multiple continuous variables13,14 and are unlikely to reflect the overall contributions of urban and rural residence as aetiological factors for the prevalence of asthma and related diseases.

Definitions for ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ which are clearer and more precise would allow for comparisons between studies and more meaningful investigations into the effect of urban and rural residence on asthma and related diseases. This review investigates definitions of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ used in publications about asthma and related diseases, including consideration of country income level for studies where specific definitions were found.

MethodsA literature search was conducted in November and December 2011 across a variety of databases including PubMed, Medline (OvidSP), ScienceDirect, Scopus and Embase. Google Scholar was used for specific article searches and reference lists of articles found were also searched. The major search terms used were ‘asthma’, ‘urban’, ‘rural’, ‘urbanisation’ and ‘urbanization’. Minor search terms included ‘definition’, ‘rhinoconjunctivitis’, ‘eczema’, ‘bronchospasm’ and ‘epidemiology’.

‘Asthma and related diseases’ included asthma, exercise induced bronchospasm, reversible airway obstruction, bronchial hyperreactivity, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema (in some studies asthma was termed an atopic disease). The main focus in this study however, was on the prevalence of asthma. The search was limited to the English language while not limited to studies on children to allow a wider search range. There was also no specified time frame for article publication dates.

Articles were included if the main topic of interest included asthma and related diseases and identified whether the location was ‘urban’ or ‘rural’. Publications were categorised into four types: a specific definition of ‘urban’ or ‘rural’; a non-specific definition; a description but no definition; the terms ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ were used but with no description or definition.

ResultsThe literature search found 73 articles which met the criteria described in “Methods” section. Descriptions of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ classifications used in the studies were found in “Methods” section in most of the articles.

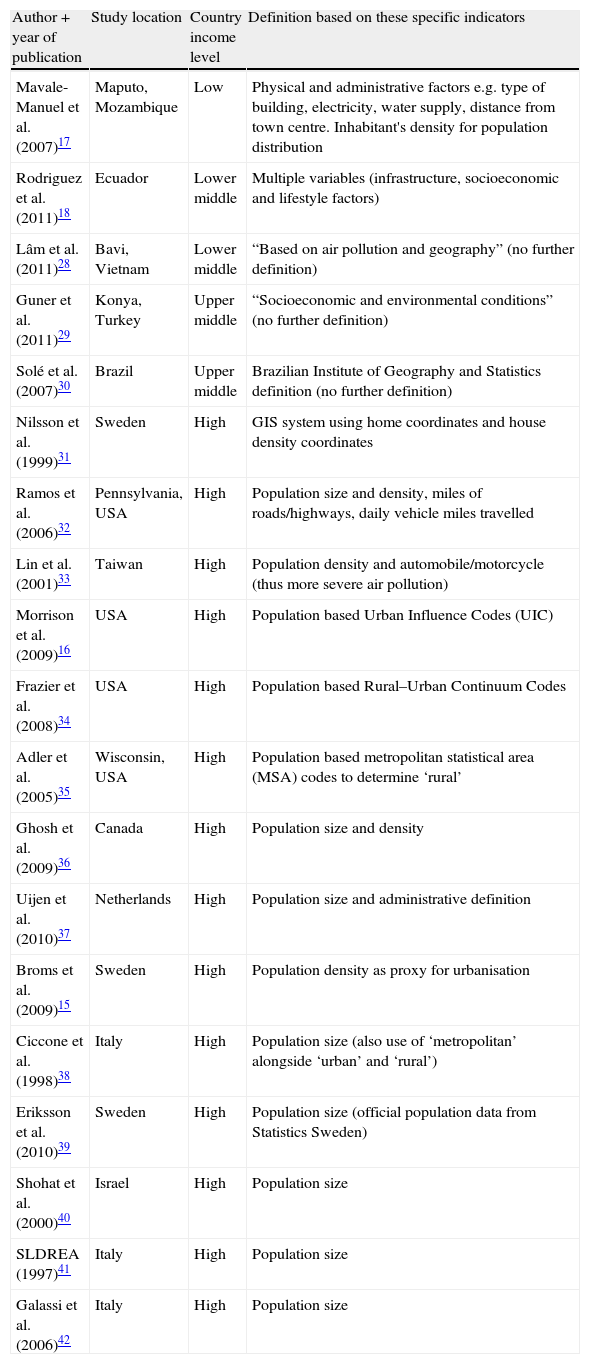

Of these 73 articles, 19 articles (26%) distinguished between ‘urban’ and/or ‘rural’ using a specific definition as described in Table 1. Most of these 19 articles used population-based definitions such as population density15 or population based Urban Influence Codes (UIC),16 particularly the studies from high income countries; two articles from low and lower middle income countries used a wider range of specific factors.17,18

Studies which distinguished between ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ using a specific definition (arranged by country income level, then by type of definition).

| Author+year of publication | Study location | Country income level | Definition based on these specific indicators |

| Mavale-Manuel et al. (2007)17 | Maputo, Mozambique | Low | Physical and administrative factors e.g. type of building, electricity, water supply, distance from town centre. Inhabitant's density for population distribution |

| Rodriguez et al. (2011)18 | Ecuador | Lower middle | Multiple variables (infrastructure, socioeconomic and lifestyle factors) |

| Lâm et al. (2011)28 | Bavi, Vietnam | Lower middle | “Based on air pollution and geography” (no further definition) |

| Guner et al. (2011)29 | Konya, Turkey | Upper middle | “Socioeconomic and environmental conditions” (no further definition) |

| Solé et al. (2007)30 | Brazil | Upper middle | Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics definition (no further definition) |

| Nilsson et al. (1999)31 | Sweden | High | GIS system using home coordinates and house density coordinates |

| Ramos et al. (2006)32 | Pennsylvania, USA | High | Population size and density, miles of roads/highways, daily vehicle miles travelled |

| Lin et al. (2001)33 | Taiwan | High | Population density and automobile/motorcycle (thus more severe air pollution) |

| Morrison et al. (2009)16 | USA | High | Population based Urban Influence Codes (UIC) |

| Frazier et al. (2008)34 | USA | High | Population based Rural–Urban Continuum Codes |

| Adler et al. (2005)35 | Wisconsin, USA | High | Population based metropolitan statistical area (MSA) codes to determine ‘rural’ |

| Ghosh et al. (2009)36 | Canada | High | Population size and density |

| Uijen et al. (2010)37 | Netherlands | High | Population size and administrative definition |

| Broms et al. (2009)15 | Sweden | High | Population density as proxy for urbanisation |

| Ciccone et al. (1998)38 | Italy | High | Population size (also use of ‘metropolitan’ alongside ‘urban’ and ‘rural’) |

| Eriksson et al. (2010)39 | Sweden | High | Population size (official population data from Statistics Sweden) |

| Shohat et al. (2000)40 | Israel | High | Population size |

| SLDREA (1997)41 | Italy | High | Population size |

| Galassi et al. (2006)42 | Italy | High | Population size |

The other 54 (74%) articles (citations are available on request) used less specific definitions. Non-specific or administrative definitions were used in nine articles (12%), for example, “large cities with urban lifestyle” vs. “mostly rural lifestyle”19 or used a metropolitan centre as ‘urban’ and locations outside of the centre being ‘rural’20 or used “doctor estimate of urban/rural ratio of clientele”.21

In 23 articles (32%), a location was stated to be ‘urban’ or ‘rural’ and then differences between the urban and rural locations were described with little or no indication of whether the description was used to make this distinction. For example, in one study, The Gambia is described as ‘urban’ but it is not clear whether the following descriptions were used to make the urban–rural distinction.22 “Banjul, the capital on an island in the River mouth, is the oldest urban settlement in The Gambia, and has a population of approximately 42,000. The Gambia has no major industry. Many of the working population in Banjul are involved in small industry, trade crafts or are employed in the civil service.”

Distinctions between ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ without a stated definition and no further description were made in 22 articles (30%). For example, “The population investigated comprised all 17 year old boys in one seaside urban area of Israel”.23

DiscussionIn this investigation of definitions of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ in articles about asthma and related diseases substantial variations were found. Most articles (74%) did not give specific definitions. Many articles simply stated whether a location was ‘urban’ or ‘rural’ before describing but not defining differences between locations. In others there was little or no description of how ‘urban’ or ‘rural’ was defined, such as using an administrative definition, making the assumption that it was intuitively obvious that a city centre was ‘urban’ and locations outside of this were considered ‘rural’. For approximately one-third of the studies, it was unclear how the distinction between ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ was made at all. In the 26% of articles where specific definitions were used, population based classifications using an urban centre and then subsequently labelling surrounding areas as rural were the most common definitions, perhaps because these are relatively simple methods for defining ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ using widely available national census data.

Very few studies used a wider range of specific indicators to define ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ including two studies on childhood asthma, one in Maputo, Mozambique17 and the other in Ecuador.18 The Ecuador study included factors such as transport access, electrical grid connection and parental education grouped under the headings of infrastructure, socioeconomic and lifestyle factors as components of urbanisation.18 The Maputo study was less explicit with regard to the definition used, citing “administrative and physical factors such as: type of building, electricity, water supply and the distance from the town centre.”17 These studies illustrate the complexities and multi-faceted aspects of urbanisation, with many variations in the trends found in disease prevalence. The Maputo study demonstrated urban–rural differences, but there were varied results between asthma, rhinitis and eczema with unclear urban–rural trends with all the diseases.17 The Ecuador study illustrated the complexity of urbanisation with mixed results among the components used in the definition; strong associations were seen between asthma prevalence and socioeconomic and lifestyle indices but weak association with urban infrastructure index.18

The literature search was focussed to answer the study question. Restricting the search field purely using the database search limits was not adequate as evidence of the use of an urban–rural distinction could only be found through evaluation of the text. Although a number of articles that defined ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ to some extent were found in the review, they are unlikely to represent all studies which have made distinctions between ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ with regard to asthma and related diseases. However, this study does give a representative view of how ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ have been defined in the literature on urban/rural residence in the context of asthma in particular.

The present review highlights a need for development in how the definition of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ is approached and described in publications. The fact that only 26% of the articles used a specific definition demonstrates the lack of emphasis on using clear and explicit definitions which are adequate for comparisons between studies. Clear specific definitions would allow researchers to determine which facets of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ are being considered in a particular study and would enable more opportunities for valid comparisons between locations. Although a standardised, universal method of defining ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ might be a potential game changer in the investigation of the effect of urbanisation, such a definition may never arise due to the enormous number of factors which occur with urbanisation and these may differ from one location to another.

Summarised country level data are readily available from world-wide sources such as the World Bank and WHO; however, more detailed data from within countries would be required for such standardised definitions, as this is not readily available on a global scale. Although high income countries might be expected to have greater availability of such data, this was not reflected in studies that had specific definitions of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’; the high income countries mostly used population based definitions. This may be an indication that such data are not available or are available but are not readily accessed or considered to be of importance. There is certainly potential for a deviation from the use of the urban–rural dichotomy towards using a continuum of urbanisation. This was evident in the Ecuador study where they referred to “measures of urbanisation”18 rather than categorising locations as ‘urban’, ‘suburban’ and ‘subrural’ as was done in Maputo.17

Two areas with the same population density may vary greatly in other environmental exposures which may be potentially influential processes of urbanisation such as parental education, access to road transport, truck traffic exposure,24 access to electricity, construction of housing, water supply, method of cooking, diet,25 and exposure to farm animals.18,26,27 Measurement of these might better inform research and policy. Certain aspects of urbanisation can be tailored to the study in question or there could be further development of an urbanisation index similar to what was done in the Ecuador study.

ConclusionThe effect of urban and rural residence has been a focus of research in asthma and related diseases but the definitions of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ are commonly broad or non-specific. At this time there is no single accepted definition which encompasses all the facets of urban and rural residence in their role in asthma and related diseases and it may be unrealistic to ever expect one. We recommend that future studies define urban and rural specifically and where possible use indicators which might be measurable in other locations so that comparisons of data might help elucidate the effect of the environment on asthma and related diseases and thus be a step towards alleviating the global burden of these diseases.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no actual or potential competing interests.

The authors acknowledge and thank the many funding bodies throughout the world that supported the individual ISAAC centres and collaborators and their meetings. Many New Zealand funding bodies contributed support for the ISAAC International Data Centre (IIDC) during the periods of fieldwork and data compilation (the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Asthma and Respiratory Foundation of New Zealand, the Child Health Research Foundation, the Hawke's Bay Medical Research Foundation, the Waikato Medical Research Foundation, Glaxo Wellcome New Zealand, the New Zealand Lottery Board, the Auckland Medical Research Foundation and Astra Zeneca New Zealand). International funding was received from Glaxo Wellcome International Medical Affairs and the BUPA Foundation. Funding for the summer studentship was received from the University of Auckland.

This work was completed by AL as a University of Auckland MBChB summer student at the Department of Paediatrics: Child and Youth Health, The University of Auckland, Level 12, Auckland City Hospital Support Building, 2 Park Road, Grafton, Auckland, New Zealand.