Several studies have demonstrated that medication is commonly used off-label in children with allergic diseases. The aim of this study was to characterise off-label use of prescriptions for allergic diseases in pre-school children from an allergology outpatient unit.

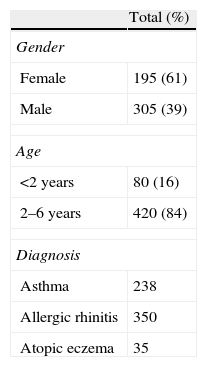

MethodsThe clinical files of children aged ≤6 years seen in a reference allergology consultation with asthma, allergic rhinitis, and/or atopic eczema were reviewed. A total of 500 patients were consecutively observed from January to June 2012. The data collected included gender, age, diagnosis, and prescriptions with the respective daily dosage.

ResultsA total of 1224 prescriptions were registered. The most prescribed medications were oral antihistamines (34.6%), antileukotrienes (22.6%), topical nasal corticosteroids (20.3%), and inhaled corticosteroids (17.7%). From all prescriptions, 422 (34.5%) were considered off-label for age (62.6%), dosage (31.7%), or clinical indication (5.7%). Off-label use was more frequent in children aged <2 years, with 73.5% prescribed for children of this age.

ConclusionsOff-label use of drugs for the treatment of paediatric allergic diseases is high. However, these prescriptions are not necessarily wrong, and are recommended in many guidelines. Randomised controlled studies are limited by methodological difficulties creating the need for more observational studies in order to further evaluate the safety and efficacy of drugs used in children.

Many drugs used in the treatment of allergic diseases are not appropriately studied in the paediatric population, especially in infants and younger children. Nonetheless, their off-label use, i.e. use outside the formal indications authorised by the regulatory authorities, in a different age group, dose, or indication1 is common in many paediatric illnesses like allergic disease. This happens because of practical and ethical considerations in carrying out clinical trials in this population.2 In general, off-label prescription rates range from 11% to 37% in children treated in the community setting, and in up to 62% of children in paediatric hospital wards.3 The major concern with this off-label use is the increased risk of adverse drug reactions.4 Additionally, younger children and infants have a considerably increased risk of prescription errors, especially dosage errors.5

However, off-label prescriptions are not necessarily incorrect,6 and may even be appropriate in certain clinical situations provided there is no alternative treatment, and when the likely benefits outweigh the potential risks,7 such as when conventional treatments are unable to achieve control of the disease. The potential advantages of off-label prescribing, apart from the probable benefit to the individual patient, are that new therapeutic uses may be described, and data on the efficacy and safety of the drug being used in new settings may be collected.8 With off-label prescriptions, the physician must act as an enlightened intermediary. On the one hand, managing the regulatory data aimed at ensuring the effectiveness and safety of the prescription, and on the other hand, putting all his or her knowledge into serving the interests of the patient.

Several studies have consistently shown that off-label use in children is common. A population-based cohort study carried out in primary care units in Holland assessed the prescribing of respiratory drugs in 2502 children, showing that almost 37% were off-label, and 39% in this group were prescriptions for asthma.9 The TEDDY study, comparing the use of anti-asthmatic drugs in children in Holland, Italy, and the United Kingdom, established that off-label use of β2-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids is frequent, including up to 80% of the inhaled budesonide prescriptions in Italy.10

In Portugal, few studies exist concerning off-label use of drugs in paediatric populations, and none are specifically related to drugs for the treatment of allergic disease. This study aimed to characterise off-label prescribing of drugs used in the treatment and control of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic eczema in a significant sample of pre-school aged children followed by allergy specialists at a reference allergology consultation.

MethodsThe clinical files of children aged ≤6 years followed in our allergology consultation who were diagnosed with current asthma, allergic rhinitis, and/or atopic eczema phenotypes, with predominantly moderate to severe clinical presentations, were systematically reviewed. Consecutive medical visits were analysed from the beginning of January 2012 until the inclusion of a total of 500 patients (June 2012).

The data collected included gender, age, diagnosis, and drugs prescribed for the control of allergic diseases that were used for a minimum period of two weeks, as well as the respective dosages. Drugs used for acute treatment were not considered. The drugs included were classified as follows: (1) inhaled corticosteroids (IC); (2) nasal topical corticosteroids (NC); (3) long acting β2 agonists (LABA); (4) oral antihistamines (AH); (5) oral antileukotrienes (AL); (6) topical immunomodulators (TI).

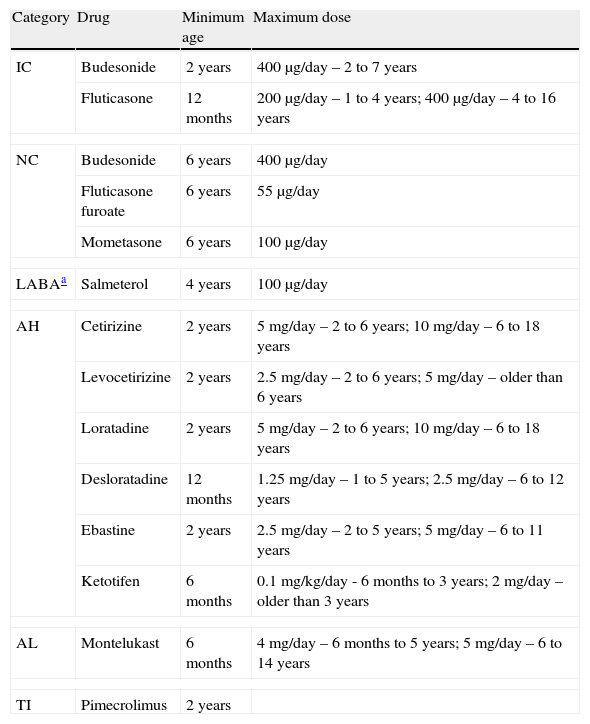

The formal indications for each drug were available from Infarmed – Autoridade Nacional do Medicamento e Produtos, I.P. (Infarmed),11 the national authority on drug control and authorisation, and were confirmed by the pharmaceutical companies responsible for their production and distribution; these indications were systematically compared by the authors, who found no discrepancies (Table 1).

Drugs used for treatment of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic eczema, and their authorizations for use according to age and dose.

| Category | Drug | Minimum age | Maximum dose |

| IC | Budesonide | 2 years | 400μg/day – 2 to 7 years |

| Fluticasone | 12 months | 200μg/day – 1 to 4 years; 400μg/day – 4 to 16 years | |

| NC | Budesonide | 6 years | 400μg/day |

| Fluticasone furoate | 6 years | 55μg/day | |

| Mometasone | 6 years | 100μg/day | |

| LABAa | Salmeterol | 4 years | 100μg/day |

| AH | Cetirizine | 2 years | 5mg/day – 2 to 6 years; 10mg/day – 6 to 18 years |

| Levocetirizine | 2 years | 2.5mg/day – 2 to 6 years; 5mg/day – older than 6 years | |

| Loratadine | 2 years | 5mg/day – 2 to 6 years; 10mg/day – 6 to 18 years | |

| Desloratadine | 12 months | 1.25mg/day – 1 to 5 years; 2.5mg/day – 6 to 12 years | |

| Ebastine | 2 years | 2.5mg/day – 2 to 5 years; 5mg/day – 6 to 11 years | |

| Ketotifen | 6 months | 0.1mg/kg/day - 6 months to 3 years; 2mg/day – older than 3 years | |

| AL | Montelukast | 6 months | 4mg/day – 6 months to 5 years; 5mg/day – 6 to 14 years |

| TI | Pimecrolimus | 2 years | |

IC: inhaled corticoids; NC: nasal topic corticoids; LABA: long acting β2 agonists; AH: oral antihistamines; AL: anti-leukotriene; TI: topic immunomodulator.

The age groups were classified according to the paediatric age definitions provided by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).12 As such, the sample was divided as follows: age<2 years, and age 2–6 years. Although EMA considers an age group for newborns “younger than one month old”, the sample did not include any patients in this age group.

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the institution.

Statistical analysisStatistical comparisons (chi-square) were performed using the statistical program IBM SPSS Statistics version 19.0.0 (2010, Chicago, IL, USA), and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

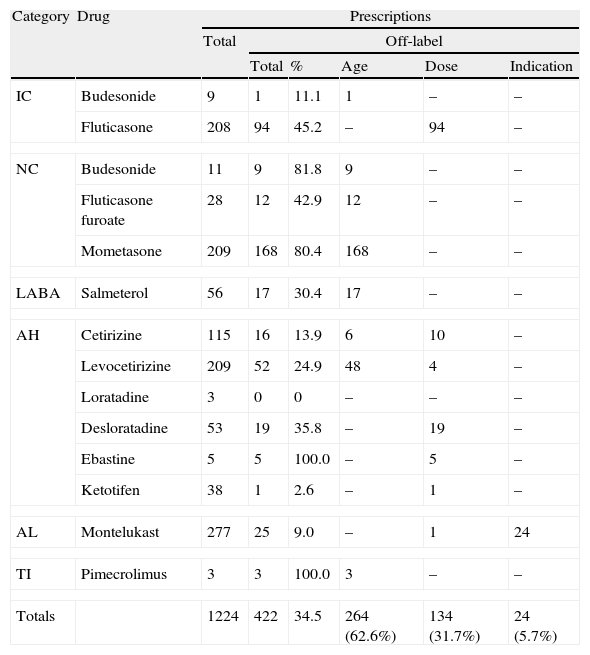

ResultsA total of 500 patient files were verified (Table 2), corresponding to 1224 prescriptions used to control the previously mentioned pathologies. The most prescribed drugs were oral antihistamines (34.6%), followed by antileukotrienes (22.6%), nasal topical corticosteroids (20.3%), inhaled corticosteroids (17.7%), association of inhaled corticosteroids and LABA (4.6%), and, finally, topic immunomodulators (0.2%). The most often used drugs were montelukast (22.6%), levocetirizine (17.1%), mometasone (17.1%), and fluticasone (17.0%) (Table 3).

Total number of prescriptions studied.

| Category | Drug | Prescriptions | |||||

| Total | Off-label | ||||||

| Total | % | Age | Dose | Indication | |||

| IC | Budesonide | 9 | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | – | – |

| Fluticasone | 208 | 94 | 45.2 | – | 94 | – | |

| NC | Budesonide | 11 | 9 | 81.8 | 9 | – | – |

| Fluticasone furoate | 28 | 12 | 42.9 | 12 | – | – | |

| Mometasone | 209 | 168 | 80.4 | 168 | – | – | |

| LABA | Salmeterol | 56 | 17 | 30.4 | 17 | – | – |

| AH | Cetirizine | 115 | 16 | 13.9 | 6 | 10 | – |

| Levocetirizine | 209 | 52 | 24.9 | 48 | 4 | – | |

| Loratadine | 3 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Desloratadine | 53 | 19 | 35.8 | – | 19 | – | |

| Ebastine | 5 | 5 | 100.0 | – | 5 | – | |

| Ketotifen | 38 | 1 | 2.6 | – | 1 | – | |

| AL | Montelukast | 277 | 25 | 9.0 | – | 1 | 24 |

| TI | Pimecrolimus | 3 | 3 | 100.0 | 3 | – | – |

| Totals | 1224 | 422 | 34.5 | 264 (62.6%) | 134 (31.7%) | 24 (5.7%) | |

Results in n, except when pointed out. IC: inhaled corticoids; NC: nasal topic corticoids; LABA: long acting β2 agonist; AH: oral antihistamines; AL: anti-leukotriene; TI: topic immunomodulator.

Of all the prescriptions, 802 (65.5%) were authorised for use in children and were used according to the formally approved indication. The remaining 422 (34.5%) drugs were used off-label, outside the approvals for age (62.6%), dosage (31.7%), or clinical indication (5.7%). Mometasone, fluticasone, and levocetirizine were the drugs most frequently prescribed in this fashion (Table 3). In Portugal, as in several other European countries, mometasone is authorised solely for children aged >6 years and is therefore frequently used off-label. The same occurs with levocetirizine, which is authorised only for children aged >2 years. As for fluticasone, its off-label use was related to prescribing doses greater than the approved dosage. Only montelukast was prescribed outside of its clinical indication since, in Portugal as in other countries, it can only be used as adjunctive therapy in the preventive treatment of asthma in children age <2 years, being not authorised as a single therapy,11 with the exception if it is not possible to use inhaled steroids as controller medication.

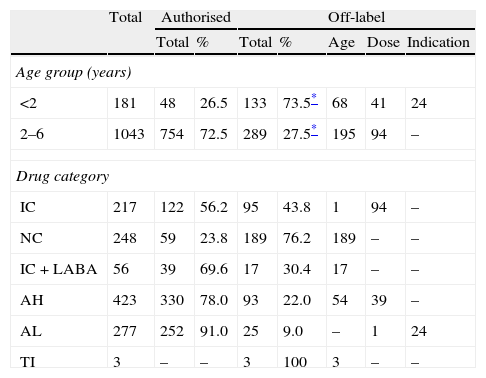

Dividing the prescriptions into categories, we highlight the off-label use of nasal topical corticoids in over 75% of the total prescription (Table 4), which was always due to the age limitation. We also note the off-label use of pimecrolimus due to age in cases of severe atopic eczema, despite its reduced prescribing in three patients aged 8, 10, and 12 months, respectively.

Prescriptions according to age and drug category.

| Total | Authorised | Off-label | ||||||

| Total | % | Total | % | Age | Dose | Indication | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| <2 | 181 | 48 | 26.5 | 133 | 73.5* | 68 | 41 | 24 |

| 2–6 | 1043 | 754 | 72.5 | 289 | 27.5* | 195 | 94 | – |

| Drug category | ||||||||

| IC | 217 | 122 | 56.2 | 95 | 43.8 | 1 | 94 | – |

| NC | 248 | 59 | 23.8 | 189 | 76.2 | 189 | – | – |

| IC+LABA | 56 | 39 | 69.6 | 17 | 30.4 | 17 | – | – |

| AH | 423 | 330 | 78.0 | 93 | 22.0 | 54 | 39 | – |

| AL | 277 | 252 | 91.0 | 25 | 9.0 | – | 1 | 24 |

| TI | 3 | – | – | 3 | 100 | 3 | – | – |

Results in n, except when pointed out. IC: inhaled corticoids; NC: nasal topic corticoids; LABA: long acting β2 agonist; AH: oral antihistamines; AL: anti-leukotriene; TI: topic immunomodulator.

Although the overall prescribing for children aged <2 years was lower than in older children, off-label use was relatively much more frequent. Up to 73.5% of prescriptions in this age group were off-label compared with 27.7% in the oldest age group (Table 4). This difference was statistically significant (p <0.001). Note that, with one exception, all children aged <2 years received at least one off-label prescription.

DiscussionThis study provides detailed and original information about national off-label prescribing for the allergic diseases asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic eczema in the paediatric population.

We found that, in pre-school children, the use of drugs for these conditions in moderate to severe forms is frequent (34.5%), particularly in children aged <2 years, with more than 73% of prescriptions made for this group. This is probably due to the absence of data on the safety and efficacy of drugs at this age group, owing to the lack of clinical trials.1–4

The lack of clinical research in the paediatric population, mainly in infants, results from a combination of factors that can contribute to this age group being the last to benefit from medical progress.2,13 Pharmaceutical companies, which can never promote or recommend off-label use of their drugs, apparently view the approval of drugs in children as a market that would bring small financial benefit, with only a few drugs representing a large enough economic interest. As such, it is not surprising that the drugs that have been adequately studied in children are anti-infectious vaccines and some antibiotics. Specific medical techniques and appropriate equipment are also necessary for clinical investigation in the paediatric population; technical procedures that seem simple in adults, such as drawing blood, among other minimally invasive interventions, can be difficult to execute or even authorise in children. Lastly, the ethical implications in children are more complex, with potential risks associated with the intervention, and significantly hinder clinical trials in this population.14

The clinical investigation of drugs in the paediatric population is regulated by international standards (ICH E11), including European (EC no. 1902/2006), which set out specific requirements for the protection of children in clinical trials.15,16 However, the current EMA regulations encourage research and development of drugs in the paediatric population to improve the available information on these drugs, by assigning benefits to the pharmaceutical industry like extending the period of patent exclusivity.17,18

Nonetheless, most drugs available on the market are not specifically tested in children, particularly younger children. In Portugal, Infarmed has specialised committees, namely the Committee for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, which is responsible for issuing opinions on the quality, safety, and efficacy of drugs within their marketing authorisations (AIM). They have the responsibility for reviewing and approving the Summaries of Product Characteristics (RCM). However, the use of drugs outside their authorised RCM is not the concern of authorities and is the sole responsibility of the prescriber.19

This study showed a great number of off-label prescriptions, although it can be overestimated related with the severity of the clinical manifestations of the included children; these values must be interpreted with caution, however, as they may suggest inadequate or inappropriate use. Off-label prescribing is not necessarily incorrect6 and is contemplated in several therapeutic guidelines that include paediatric populations, but remarkably with no indication that some of the drugs are being recommended for unlicensed and off-label use.20 In fact, indications for drug use in therapeutic guidelines do not clinically or legally authorise their use, even if the guidelines support it.

Off-label prescribing is frequently necessary, but should be evaluated according to clinical indications, therapeutic alternatives, and risk-benefit considerations, and off-label use implies obtaining informed consent from the patient or guardian. However, if off-label use of drugs does not require a signed informed consent by the patient or his or her legal representative, is oral consent enough? In the prescriptions studied, off-label drug use was systematically indicated and justified to the parents or caretakers as well as the clinical necessity for the drug's use, which was invariably authorised after the requested clarifications, increasing the compliance to the indicated treatments. This type of information is very important for patient and caregiver adherence, but it is often omitted. A survey conducted in the UK found that most paediatricians did not obtain informed consent, or inform the children's parents that the drug's use was off-label, which could indicate poor medical practice.21

From the prescriptions studies, we note the very frequent off-label use of a very safe topical nasal corticosteroid, mometasone. The reason for off-label use was entirely due to its use outside the authorised age group, as it is only approved for children aged ≥6 years. This imposition is made by EMA, whereas the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) already allows the use of this drug in younger children, i.e. those aged >2 years.22 Despite the discrepancy in permissions, the fact that the FDA, which is responsible for the regulation of drugs in the United States, has already authorised broader use of this drug offers additional security for prescribing it off-label in Europe. If the authorisations were identical, off-label use of mometasone would be only 4.3%.

The same can be said of the use of some antihistamines, in particular levocetirizine, whose off-label use was approximately 25%, and almost entirely due to its use in children aged under the authorised age. As of 2009, the FDA approved prescribing this drug for children and infants from six months of age22 after publication of long-term trials that demonstrated its safety and efficacy in this paediatric population.23 In our pharmaceutical market, levocetirizine is still only approved for children aged >2 years.11 As in the above-mentioned case, if the indications were the same on both continents, off-label prescribing of this drug would have been irrelevant.

Regarding topical immunomodulators, pimecrolimus was prescribed for only three cases of atopic eczema, but always off-label for age, despite its use being justified by clinical severity. This pathology appears in over 60% of patients before the age of 12 months;24 however, these drugs are only approved for children aged >2 years by both the FDA and EMA.11,22,25 This limitation was imposed because there are no current studies of long-term safety that are deemed sufficient for approval in younger children. The concerns of the regulatory authorities are based on the theoretical risk of systemic immunosuppression derived from the use of oral calcineurin inhibitors such as pimecrolimus or tacrolimus in transplant recipients, and the existence of rare instances of malignancy associated with their use.26 However, pharmacokinetic data obtained from clinical trials in children aged <2 years did not suggest concentrations high enough to cause systemic immunosuppression, unlike oral administration, or demonstrate a correlation between systemic concentrations and percentage body surface area treated or the duration of treatment.27 Likewise, there was no interference with the development of normal immune responses to vaccinations.28 Besides demonstrating extreme efficacy, these trials demonstrate safety data for IT use in atopic eczema, but more extensive surveillance is needed to determine long-term safety. Nonetheless, since its introduction on the market in 2001, no definite causal relationship between the use of IT and malignancy has been established.26

In this study, we confirmed that the off-label use of anti-allergic drugs in pre-school-aged children for the treatment of moderate to severe allergic diseases is high. With few studies of long-term safety, the implications inherent in this type of use become evident. The Paediatric Committee of the EMA has issued a list of drugs currently administered to children for which information on pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety are urgently needed; fluticasone and montelukast, among others, were included.29 The standard method consists of performing randomised controlled trials, which are limited by methodological difficulties, hence the need to develop sufficiently extensive post-marketing observational studies in order to obtain sufficient data to evaluate the safety and efficacy of drugs used in paediatric populations.

In some emerging diseases in our area of expertise the majority of drugs available that provide the best results are used off-label regardless of age.30

The presence of complete and updated records with detailed information on the drugs used, dosages, routes of administration, and adverse effects are important in obtaining reliable data essential for further evaluation of the safety and efficacy of drugs in which more complex studies in children are not feasible for practical and/or ethical reasons. As with other populations with unique characteristics, such as pregnant women and the elderly, publication and distribution of this information by the scientific community is critical for the acquisition of new safety data, allowing the approval of new dosages, clinical indications, and/or prescribing for younger children, reducing off-label drug use that, although often appropriate, is not without risks.

Finally, this study should increase clinicians’ awareness of prescribing drugs off-label such that they are available at any time to discuss use of the drugs with patients and their families, as well as provide the motives that justify their use, valuing benefits versus risks, increasing compliance and contributing to achieve better outcomes.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestNone to declare.