Chronic granulomatous disease is a phagocyte defect, characterised by recurrent infections in different organs due to a defect in NADPH oxidase complex. This study was performed to investigate pulmonary problems of CGD in a group of patients who underwent computed tomography (CT) scan.

MethodsComputed tomography scan was performed in 24 patients with CGD. The findings of the CT scan were documented in all of these patients.

ResultsAreas of consolidation and scan formation were the most common findings, which were detected in 79% of the patients. Other abnormalities in order of frequencies were as follows: small pulmonary nodules (58%); mediastinal lymphadenopathy (38%); pleural thickening (25%); unilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (25%); axillary lymphadenopathy (21%); bronchiectasis (17%); abscess formation (17%); pulmonary large nodules or masses (8%); and free pleural effusion (8%).

ConclusionThe pulmonary CT scans of the patients with CGD demonstrated a variety of respiratory abnormalities in the majority of the patients. While recurrent respiratory infections and abscesses are considered as prominent features of CGD, early diagnosis and precise check-up of the respiratory systems are needed to prevent further pulmonary complications.

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), which was first introduced as fatal granulomatous disease of childhood in the 1950s,1 results from defects in NADPH oxidase complex, the enzyme responsible for production of superoxide anion and downstream antimicrobial oxidant metabolites. Five different genes have been identified so far which have mutations that lead to CGD.2 X-linked type of the disease is caused by a defect in gp91phox subunit of the enzyme, which consists in about 70% of the cases. Other less common mutations in CGD patients are inherited in autosomal recessive pattern, including p47phox, p67phox, p22phox, and p40phox.2,3 As an inherited immunodeficiency, CGD presents with a wide range of clinical variability. Bacterial and fungal infections and granuloma formation due to abnormally exuberant inflammatory responses in multiple organs are the main manifestations of the disease,4 which mainly present in the respiratory system, followed by lymph nodes, cutaneous, gastrointestinal system.5,6Staphylococcus aureus, Burkholderia cepacia, Serratia marcescens, Nocardia, and aspergillus spp. are considered as the major organisms responsible for infections in CGD patients worldwide. However, involvement with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), tuberculosis, and Salmonella has been reported in some countries.3,4,7,8 Pneumonia seems to be the most prevalent infectious lung manifestation of CGD patients, while about half of the patients could suffer from lower respiratory tract infections; meanwhile abscess formation is also common in CGD. Other less common lung involvements are pleural effusion, bronchiectasis, and bronchitis.5,9–11 It seems that repeated infections or unregulated airways inflammation can lead to granulomatous and autoimmune manifestations. Imbalance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators may be the trigger of deregulated inflammation in CGD.12

It should be emphasised that early diagnosis and rapid treatment of infections are critical in CGD. Prophylaxis with antibacterial and mould-active antifungal agents and administration of interferon-γ has significantly improved the prognosis of patients with CGD during recent decades.13 Although allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is considered as the only curative therapy for CGD, its indications remain controversial.14 As respiratory problems in CGD could be associated with some non-specific symptoms, understanding on the pattern of infection, inflammation, and granuloma formation could provide a clue for diagnosis of possible complication. The aim of this study was to assess findings of computed tomography (CT) scan in a group of patients with CGD who suffered from respiratory manifestations.

Patients and methodsThis survey was conducted on 24 patients with confirmed diagnosis of CGD, who had been referred to the National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases, Masih Daneshvari Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (the main referral centre for pulmonary diseases in the country) over a 10-year period (October 2001–April 2012). The diagnosis of CGD was verified according to determination of abnormal neutrophil function test evaluated by nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) test in two consecutive tests, in which an absent reaction or a reaction of <5% cells was characteristics of CGD.15 We retrospectively evaluated the CT scan findings of all these patients. The CT scans were carried out by using a single detector scanner (HiSpeed, GE Healthcare) at end-inspiration phase. Three expert chest radiologists in consensus reported the chest CT scan findings, by using a designed chart, which included presence or absence of nodules, abscess, axillary or mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy, bronchiectasis, ground-glass opacity, consolidation, pleural effusion or thickening, chest wall extension, and scar formation. In accordance with the standardised nomenclature,16 consolidation was considered as a homogenous augmentation in lung parenchyma attenuation that obscures the borders of the airway walls and vessels; ground glass appearance was reported as a homogenous, hazy region of increased attenuation without obscuration of bronchovascular markings; pleural effusion was considered as fluid within the pleural cavity, which was detected by CT scan. Lymphadenopathy was defined as enlarged hilar or mediastinal lymph node detectable by CT scan. Bronchiectasis was defined as irreversible dilatation of a bronchus.

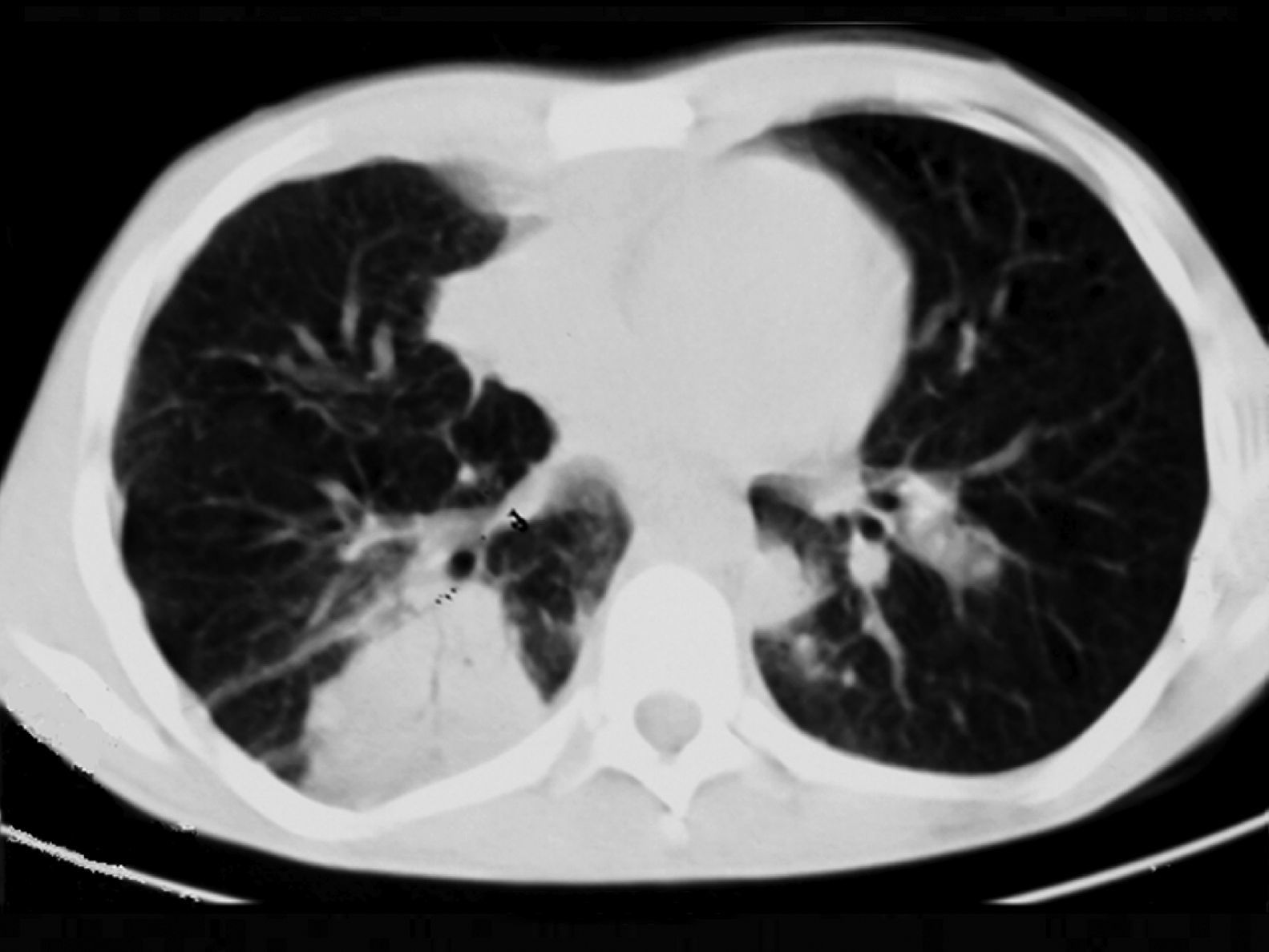

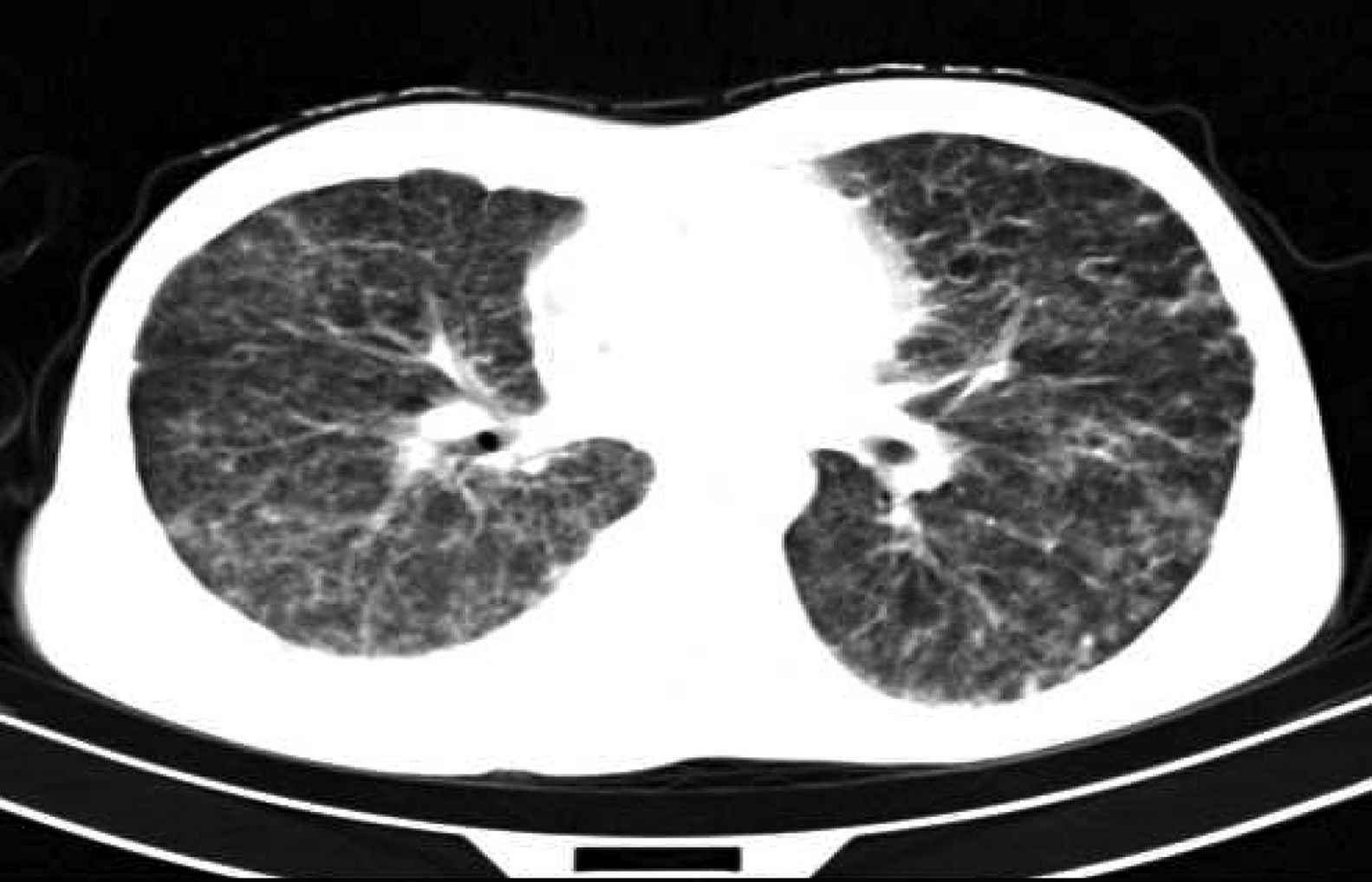

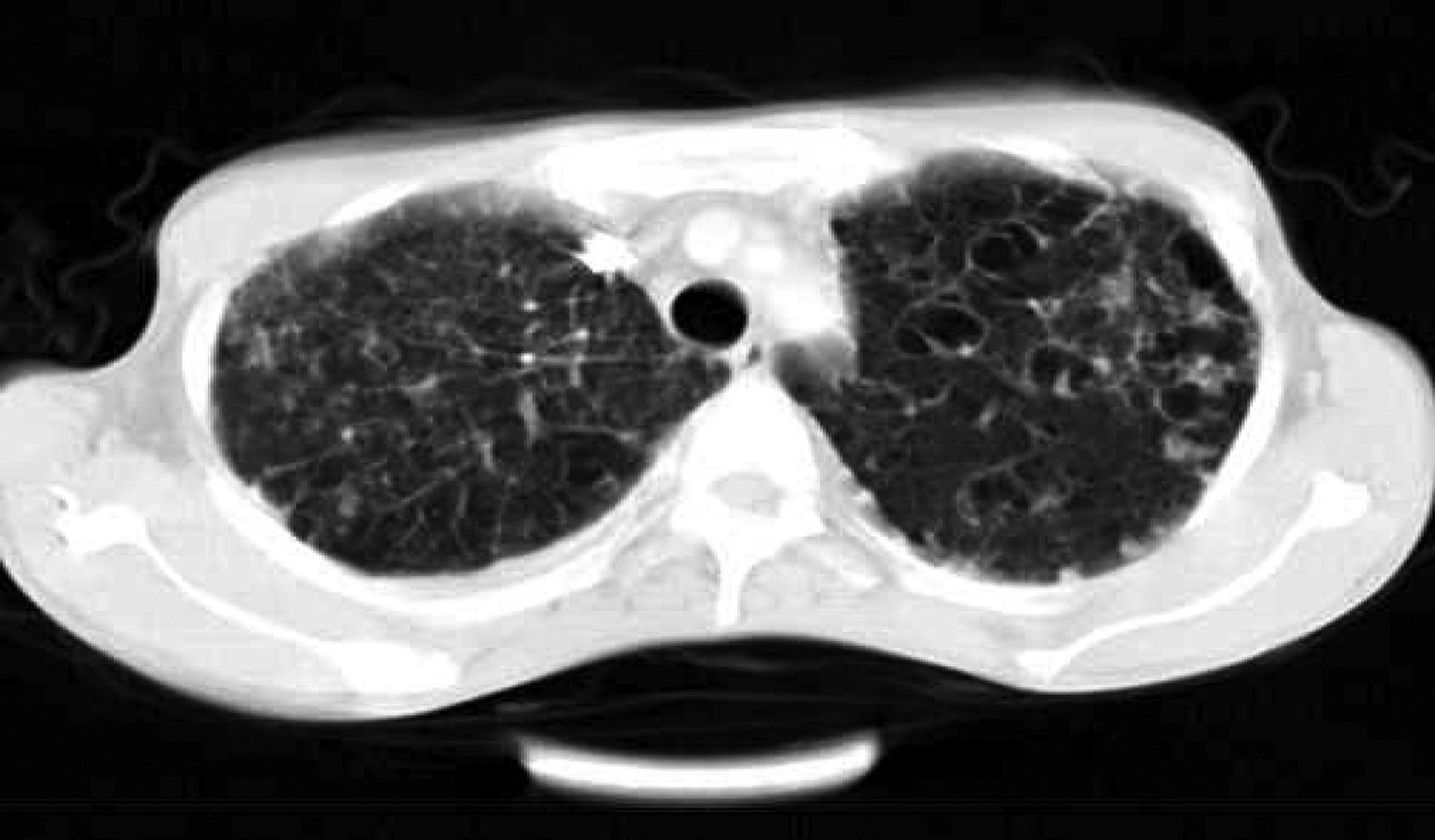

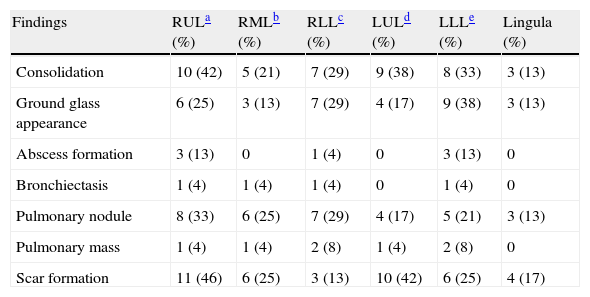

ResultsTwenty-four patients’ CGD (14 male and 10 female), with mean age of 4.2±1.5 years at the time of diagnosis, were investigated in this study. The mean age of the patients at the time of recent admission was 17.4±5.7 years. The main reason of admission in 21 cases was respiratory tract infections and in the remaining three cases were skin, liver, and spleen abscesses, respectively. In all of these patients, abnormal chest CT findings were detected. Areas of consolidation were detected in 19 patients (Fig. 1). Chest CT scans showed ground-glass opacities in fourteen patients, mainly involving the lower lobes. Tiny pulmonary nodules in a random distribution were found in 14 patients (Fig. 2). Larger pulmonary nodules were detected in two cases. In CT of four patients, areas of bronchiectasis were seen (Fig. 3). Scar formation, predominately involving the upper lobes, was found in 19 patients. The localisation of the mentioned pathologies is summarised in Table 1. The most common pathologies in pulmonary CT of these patients were consolidation (79%) and scar formation (79%). Upper lobes of both lungs were the most frequent location of consolidation and scar formation (p=0.06). On the other hand, pulmonary nodules in the right lung were more common than in the left side (p=0.0003). Free pleural effusion was found in two patients. Chest wall extension was not reported in any of our series. Pleural thickening was shown in six patients of our series. Abscess formation was reported in four cases (Fig. 4). Mediastinal lymphadenopathy, unilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, and axillary lymphadenopathy were detected in nine, six and five patients, respectively.

Localisation of main pulmonary CT scan findings in adult patients with CGD.

| Findings | RULa (%) | RMLb (%) | RLLc (%) | LULd (%) | LLLe (%) | Lingula (%) |

| Consolidation | 10 (42) | 5 (21) | 7 (29) | 9 (38) | 8 (33) | 3 (13) |

| Ground glass appearance | 6 (25) | 3 (13) | 7 (29) | 4 (17) | 9 (38) | 3 (13) |

| Abscess formation | 3 (13) | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 3 (13) | 0 |

| Bronchiectasis | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Pulmonary nodule | 8 (33) | 6 (25) | 7 (29) | 4 (17) | 5 (21) | 3 (13) |

| Pulmonary mass | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 0 |

| Scar formation | 11 (46) | 6 (25) | 3 (13) | 10 (42) | 6 (25) | 4 (17) |

Chronic granulomatous disease is considered a hereditary immunodeficiency disease, characterised by incapability of phagocytes in order to efficiently kill ingested pathogens, particularly catalase-positive organisms as a result of NADPH oxidase deficiency, resulting in recurrent pyogenic infections, particularly pneumonia.3,17–20 Previous authors have explained radiological signs of chronic or recurrent pneumonia, such as empyema,20 abscess formation,21 osteomyelitis of the vertebral bodies and ribs,20,21 hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy,20–22 and chest wall invasion.20–26 None of our patients had chest wall invasion, but lung abscess was found in four patients of our series. Fibrotic changes and pulmonary scarring have previously been reported in paediatric CGD cases.20,27 Similarly nineteen patients of our series had pulmonary scarring. Bronchiectasis was not a significant presentation, while it was found in the CT of four patients. Persistent axillary or hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy was a frequent finding in our patients; it was detected in half of the cases, in agreement with that previously described.20,21 To the best of our knowledge, the common locations of various pulmonary pathologies in CGD have not been investigated yet. We found that upper lobes of both lungs are the most frequent location of consolidation and abscess; on the other hand, pulmonary nodules in the right lung were significantly more common than in the left side. To understand the reason for this difference, designing another study could be suggested to evaluate the microorganisms causing these pathologies and to compare its association with the segment involvement. In addition, the most common pathologies in our patients’ pulmonary CT scan were consolidation and scar formation. Infections always seem a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, because patients may refer with fairly mild clinical symptoms and signs, while the responsible pathogen can be difficult to detect. Early lung biopsy might be essential in patients with CGD and pneumonia, especially if there has not been a clinical response to empiric therapy focusing on the common causative organisms. Percutaneous fine-needle aspiration prior to antibiotic therapy has been suggested,4 but relative yield and the timing of different investigations (such as transbronchial, and open lung biopsy, fine-needle aspiration) in this setting has not been assessed. Based on previous studies in about 50% of patients, diagnostic procedures such as needle biopsy or bronchial lavage were successful in identifying pathogenesis.12

The most common findings in CT scan of CGD patients include consolidation and pulmonary nodules. These pathologies could be considered as the consequence of acute infection or chronic granulomatous inflammation. Other usual presentations in these patients are areas of pulmonary scarring and bronchiectasis. It should be noted that radiologists have an important role in the diagnosis of pulmonary complications of CGD and must be alert about most common pulmonary radiological presentations in adult patients.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Protection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.